Roz Savage's Blog, page 22

September 20, 2018

The Great Transition

Over the years my thinking has been shaped by an essay I first read at least 7 years ago, possibly longer, when its clarity and urgency really resonated with my heart and mind.

Paul Raskin

Paul Raskin

The essay is Great Transition, by Paul Raskin of the Tellus Institute. If you haven’t read it, I urge you to do so, and I’ve added downloadable pdfs at the bottom of this blog post – or please at least read the summary I’m about to share with you.

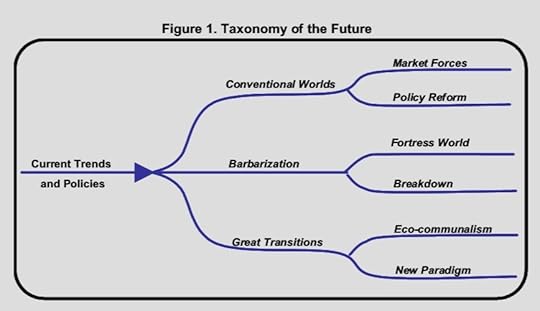

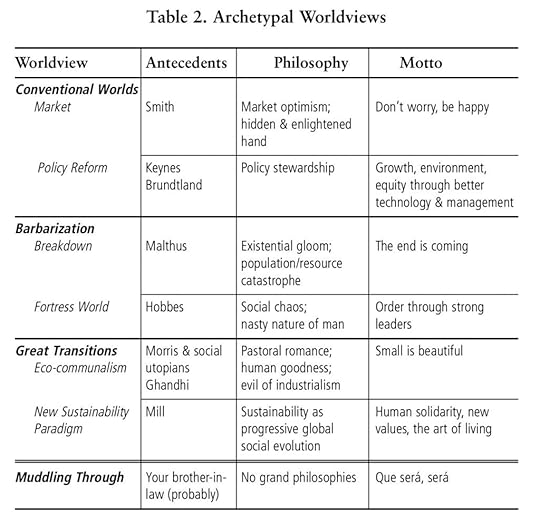

Raskin envisages six possible scenario types emerging as we head into the future:

Conventional Worlds: more or less business as usual, these two scenarios arise gradually from the dominant forces of globalization—economic interdependence grows, dominant values spread, and developing regions converge toward rich-country patterns of production and consumption.

Market Forces: economic growth continues to be a priority, through neoliberal policies such as free trade, privatization, deregulation, and the modernization and integration of developing regions into the global market.

Policy Reform: as for Market Forces, plus comprehensive governmental initiatives to harmonize economic growth with a broad set of social and environmental goals.

These two scenarios might sound reassuringly normal and predictable, but are they possible? They must reverse destabilizing global trends—social polarization, environmental degradation, and economic instability—even as they advance the consumerist values, economic growth, and cultural homogenization that drive such trends. There are many who doubt that sustainability can be reconciled with the conventional development paradigm, in which case these scenarios could veer off towards….

Fortress World: elites in protected enclaves defend themselves against an impoverished majority outside (some parts of the world already look like this), or….

Breakdown: in which conflict spirals out of control, waves of disorder spread, and institutions collapse.

At the more optimistic end of the spectrum we have two Great Transitions scenarios; transformative futures in which a new suite of values ascend— human solidarity, quality-of-life, and respect for nature—that revise the very meaning of development and the goal of the “good life”. In this vision, solidarity is the foundation for a more egalitarian social contract, poverty eradication, and democratic political engagement at all levels. Human fulfilment in all its dimensions is the measure of development, displacing consumerism and the misleading metric of GDP. There emerges an ecological sensibility that understands humanity as part of a wider community of life is the basis for true sustainability and the healing of the Earth.

One possibility is Eco-communalism, a highly localist vision favoured by some environmental subcultures. But the plausibility and stability of radically detached communities in the planetary phase are problematic. So Raskin comes down in favour of…

New Sustainability Paradigm: this recognises an opportunity for forging new categories of consciousness—global citizenship, humanity-as-whole, the wider web of life, and sustainability and the well-being of future generations. The new paradigm would change the character of global civilization rather than retreat into localism. It validates global solidarity, cultural cross-fertilization and economic connectedness, while seeking a humanistic and ecological transition. It celebrates diverse regional forms of development and multiple pathways to modernity.

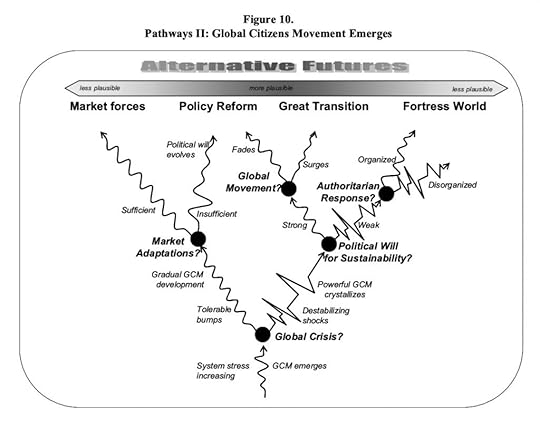

How do we make this happen? Raskin sees the force for change being a Global Citizens Movement (GCM), which has “a shared vision for the global future, a common identity as global citizens, and a sophisticated strategy for change. It would coalesce around a global vision that is both hopeful and rigorously grounded. It would evolve an integrated framework for mutually supportive action. It would balance the needs for unity and coherence with respect for diversity and autonomy, rejecting both the stultifying top-down movements of the past and the incoherent bottom- up politics of the present. The GCM would be a broad cultural and political project, a popular harbinger of a new planetary civilization.”

This could emerge from our existing global civil society, once it transcends its current “significant limits—fragmentation around a thousand separate issues, organizational entrenchment, and the negative politics of protest”. What is needed is a “diverse and plural process of people from every corner of the world, across cultures, classes, and places. It would be an expanding arena of popular participation, cultural ferment, and political activism. It would engage the full spectrum of issues. It would cluster this diversity under the umbrella of an inspiring and inclusive global vision, rooted in a rigorous understanding of global conditions. It would practice a politics of trust, seeking to reconcile proximate differences on the path to a common global future.“

This may seem like a tall order, but Raskin seems optimistic. He concludes: “The systemic framework clarifies Margaret Mead’s dictum: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world. Indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has”. At transitional moments, such as ours, small actions can have big impacts. The efforts of an engaged few can ripple through the cultural field, amplifying and influencing the global trajectory.“

So this is our work. This idea of a GCM has informed my concept for the Sisters – a GCM that starts with the female half of humanity. An essential part of the Sisters vision is to join forces with existing organisations to form a movement for change.

What about you? Are you ready to be part of a Global Citizens Movement? Are you ready to add your voice to the many who are already clamouring for positive, conscious transformation? This is no time to be a bystander. This is the time to be a global citizen.

Links to downloadable pdf files:

Other Stuff:

Many thanks to all of you who responded to my request for additional speaking engagements while I am in the US in October/November. Miriam has been busy handling all the enquiries, and jigsaw-piecing them into my schedule. I hope to see many of you very soon!

My sister, Tanya, and her boyfriend, Neil, are on the final stretch of the Continental Divide Trail. It has been an epic 5-month journey, from the Mexican border to the Canadian border, and it’s exciting to see the end in sight. Also a joy to see the gorgeous photos they post on their blog. Please cheer them on for their final leg!

September 6, 2018

Of Tardigrades and Tectonics

As humans, we’re not very good at contemplating our own mortality, let alone the demise of our planet. And yet, eventually, everything comes to an end.

I found this National Geographic article fascinating, about how the dance of our tectonic plates will eventually grind to a halt as the Earth cools, which one scientist estimates will take place around 1.45 billion years from now. According to the article, this will lead to the failure of Earth’s magnetic field, our atmosphere will be stripped away, and the oceans will evaporate.

As scientist Ken Hudnut says, in a masterpiece of understatement, “There is not a lot to look forward to after plate tectonics’ demise”.

The humble tardigrade. I’m sure its mother loves it.

The humble tardigrade. I’m sure its mother loves it.Not that we’re going to be around to have nothing to look forward to. We as a species will be long gone by then. It’s humbling to note that the “species most likely to survive” is the humble tardigrade, an eight-legged invertebrate that can survive for up to 30 years without food or water, can endure wild temperature extremes, radiation exposure, and continues unperturbed even when it finds itself in the vacuum of space. Having a big brain obviously isn’t the key to survival.

On a different subject, that somehow feels related, I was sad to hear from my mother about an act of mindless vandalism that took place at Brimham Rocks in Yorkshire, near where she lives, in which a 320-million-year-old rock formation was destroyed. A balancing sandstone rock was toppled off its crag, smashing apart when it hit the ground below.

Just to give you some idea of what a long time 320 million years is in the lifetime of the Earth, this is what geologists believe the world will look like a mere 250 years from now – one massive supercontinent, which they’re calling Pangaea Proxima. (Pangaea means “entire Earth”, Gaea being an alternative spelling of Gaia, the term that James Lovelock coined for the Earth as a self-regulating, complex system designed to maintain liveable conditions on our planet.)

So, in the overall scheme of things, I don’t suppose it matters too much that a group of vandals smashed a rock. In the year 250,002,018 A.D., when London is near the northernmost point of land, New York is smooshed up against Africa, and Australia has collided with China, their act of wanton destruction will have long paled into insignificance.

But in the short term, I can’t help feeling that we as humans have lost something, and it’s more than just a balancing rock – it’s a reverence for this amazing planet that we are lucky enough to call home.

Other Stuff:

Thanks for the fantastic response to my request last week for additional speaking engagements in the US. Miriam now has her work cut out to weave all the jigsaw pieces into a plan. I hope to see many of you in October/November this year!

Next week I’m off to Toronto to take part in the SEEDS Leadership Program, and have a few meetings. I’ll also be taking part in the first global simulcast by SheEO, using radical generosity to support female entrepreneurs.

So no blog post next week, but I’ll report back the week after.

Until then, be well, and respect nature!

August 30, 2018

Coming to a Theatre Near You?

I rarely ask for anything on this site/newsletter – I aim to give far more than I get (although in fact the giving is a kind of getting because I really enjoy it!).

Anyhow, now I am asking you to consider a possibility, especially if you live in the US near DC, Baltimore, San Francisco or Los Angeles. If you live in India, especially in or near New Delhi, please also keep reading.

Anyhow, now I am asking you to consider a possibility, especially if you live in the US near DC, Baltimore, San Francisco or Los Angeles. If you live in India, especially in or near New Delhi, please also keep reading.

A number of organisations have asked me to come and speak in the US this autumn, but as nonprofits, they have limited budgets. They can cover my travel and accommodation, but have nothing to spare for an honorarium. If I’m going to take 2-3 weeks out of my life, pay the bills, and better justify my carbon emissions, I need to rustle up some paid speaking engagements as well.

So, if you work at a company, or have a well-endowed non-profit, or have a generous circle of friends, or are a member of a club or society, or in any other way have access to a venue and funds, and would like to have me come and speak, please get in touch.

As you’ll know as a regular reader of this blog, I can talk on a range of topics, as rowing across oceans is an excellent metaphor for most challenges that crop up on life’s journey. Favourite subjects include:

TED Talk

TED Talk

Courage

Leadership for uncertain times

Mindset and motivation

Stories we tell ourselves (which become our reality)

Sustainability

Women and the future

More about these topics, plus my CV, here.

Showreel here.

Testimonials here.

Miriam Staley

Miriam StaleyI’m currently expecting to be in the US from approximately 25th October to 15th November. Events can also include a book signing.

For more details on fees and availability, please get in touch with my amazing manager, Miriam Staley, at Leading Minds Worldwide.

Email: [email protected]

Phone: +44 7771 707951 (Central European time zone)

Now to India. My wonderful friends at Vedica Scholars have invited me to come and teach my short course on courage again this year, as I did in December last year. I’d very much like to do this, but as a relatively new scholarship scheme they have very little budget for visiting teachers. So I’m seeking opportunities for paid speaking engagements while I am in New Delhi this coming December. Again, Miriam is the point of contact.

I look forward very much to hearing from you – and hope there will be an opportunity to see you in person very soon!

August 16, 2018

Of Equality, Ecology and Economics

Vandana Shiva

Vandana ShivaI’ve been reading Ecofeminism, by Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies. Even if you don’t have much time for the idea of feminism – maybe because you think it’s an attack on men, or because you associate with denim dungarees and bra-burning – please bear with me. What I have taken away from the book so far definitely has the emphasis on eco, and less on the feminism. (Of course, this may not be what the authors intended, but that is entirely my fault, not theirs.)

What surprised me with Ecofeminism was that I had expected it to be primarily about ecology and feminism (which was not entirely unreasonable, given the title). But it also talks a lot about the economy, which goes to show how much these systems are interconnected.

The book was first published 25 years ago, but unfortunately is more relevant than ever. It meshes tightly with other books I’ve read this year – The Divide, Walk Out Walk On, Rethinking Money, The Chalice and the Blade, among others. When you’re hearing the same fundamental message coming from multiple different sources, written over the course of several decades, it’s worth paying attention.

The broad conclusions of the book are:

1. Economic activity should be aimed at satisfying basic human needs, NOT the purchase of commodities and luxuries. This implies values of self-sufficiency, decentralisation, and use rather than exploitation.

2. We need to create new relationships to underpin this new kind of economic activity:

a) with nature: the interaction between humans and nature should be based on respect, cooperation, reciprocity, and the recognition that humans are part of nature. (Amen!)

b) among people: our current money/commodity relationships need to be replaced by reciprocity, mutuality, solidarity, reliability, caring and sharing, respect for the individual and responsibility for the whole.

3. Democracy should be grassroots and participatory, and cover all economic, social, and technological discussions (most of which are not participatory at the moment). Political responsibility and action should be assumed by all of us, not just elected representatives (because, heaven help us, not all of them are up to the job).

4. Problem-solving should be synergistic, based on the recognition that systems and problems are interconnected, and so will be their solutions. One of the main insights of ecofeminism is that all life on earth is interconnected, so reductionist approaches don’t work.

4. Problem-solving should be synergistic, based on the recognition that systems and problems are interconnected, and so will be their solutions. One of the main insights of ecofeminism is that all life on earth is interconnected, so reductionist approaches don’t work.

5. A new paradigm of science, technology and knowledge will recognise that research is not the value-neutral exercise in objectivity that we pretend it is. There will be a more holistic model that recognises that both the researcher and the researched affect scientific results. The new science will incorporate older survival wisdom alongside modern knowledge, and will promote social justice.

6. Culture and work will be reintegrated, as both burden (we have to work) and pleasure (work gives us meaning). The main aim of work will be happiness and a fulfilled life.

7. The commons will not be further privatised or commercialised. Under the current model, land that is being used by subsistence farmers does not figure in GDP because they consume what they produce. When the land is appropriated by commercial ventures in order to be made “economically productive”, these people are displaced and thrust into poverty. In the future, the commons of water, air, waste, soil and resources will be entrusted to shared responsibility, preserved and regenerated. (See also the work of Elinor Ostrom, the only woman ever to win the Nobel Prize for Economics.)

8. Men and women will share responsibility for the creation and preservation of life, i.e. men will share in unpaid subsistence work in the household, with children, with the old and sick, in ecological work, and in subsistence production. This is still seen primarily as “women’s work”, and the women who do it are designated as “economically inactive”, even though society could not survive without their contribution.

9. Demilitarisation of men and society: society will no longer base its concept of a good life on the exploitation and domination of nature and other people.

My big a-ha moment from the book was the message, oft repeated by the authors, that the high standard of living enjoyed by the Global North is not just at the historical expense of the South, but absolutely depends on the ongoing exploitation of the South, particularly its women and children, but to the detriment of all its inhabitants.

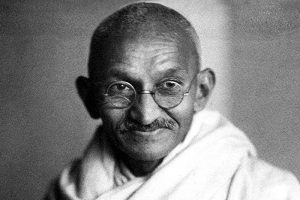

Gandhi

GandhiGandhi put it well, when a journalist asked him if he would like India to have the same standard of living as Britain: “To have its standard of living, a tiny country like Britain had to exploit half the globe. How many globes will India need to exploit to have the same standard of living?”

Maria Mies concludes the book by writing: “even if there were more globes to be exploited, it is not even desirable that this development paradigm and standard of living was generalised, because it has failed to fulfil its promises of happiness, freedom, dignity and peace, even for those who have profited from it.”

Who knows if what Vandana Shiva and Maria Mies are suggesting will work? But we do know for sure that what we have now is not working. According to The Divide, any amelioration in the plight of the world’s poor is an illusion created by massaging the figures to “prove” the success of the capitalist experiment. Hundreds of species go extinct every day. The climate is changing. Inequality is increasing. Mental health issues and over-medication are reaching epidemic proportions.

Something needs to change. This could be at least a part of the solution.

And now for some light relief!

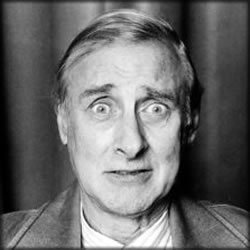

Spike Milligan

Spike Milligan“If you would know what the Lord God thinks of money, you have only to look at those to whom he gives it.” – Maurice Baring

“All I ask is a chance to prove that money can’t make me happy.” – Spike Milligan

“Wealth is any income that is at least $100 a year more than the income of one’s wife’s sister’s husband.” – H. L. Mencken

“There is nothing in the world more reassuring than an unhappy lottery winner.” – Tony Parsons

“To suppose, as we all suppose, that we could be rich and not behave as the rich behave, is like supposing that we could drink all day and keep absolutely sober.” – Logan Pearsall Smith

“The rich would have to eat money, but luckily the poor provide food.” – Russian proverb

August 2, 2018

In Praise of Trees

On Sunday night I was woken at 2am by the sound of chainsaws. My first thought that I was dreaming – I’ve been reading The Overstory, by Richard Powers, which is about trees and the courageous stand taken by a small number of humans to protect America’s last few acres of virgin forest, so chainsaws feature heavily – but as I became more and more awake, I realised that these chainsaws were for real.

We were staying at my brother-in-law’s millhouse, down in Sussex, and it turned out that the blustery winds, as well as bringing some much-needed rain to the parched English countryside, had also brought down a tree across the road, about 10 yards from our bedroom window. Workmen had shown up to clear the branches and make the road passable.

Yet it was also a sign of how much this book has seeped into my consciousness, that my first half-awake thought was to rush out and defend a tree. I rarely read fiction, but I highly recommend The Overstory.

Yet it was also a sign of how much this book has seeped into my consciousness, that my first half-awake thought was to rush out and defend a tree. I rarely read fiction, but I highly recommend The Overstory.

The writing is lyrical and evocative, and the main message I’m taking away from it is how interconnected our forests are. We may talk about not seeing the wood for the trees, but in fact, the wood is the trees – together, the trees form a super-organism that is so much more than the sum of its parts. As the Overstory blurb on Amazon says, “There is a world alongside ours – vast, slow, interconnected, resourceful, magnificently inventive and almost invisible to us.”

Some gems from the book:

“…trees are social creatures. It’s obvious to her: motionless things that grow in mass mixed communities must have evolved ways to synchronize with one another.”

“The things she catches Doug-firs doing, over the course of these years, fill her with joy. When the lateral roots of two Douglas-firs run into each other underground, they fuse. Through those self-grafted knots, the two trees join their vascular systems together and become one. Networked together underground by countless thousands of miles of living fungal threads, her trees feed and heal each other, keep their young and sick alive, pool their resources and metabolites into community chests …. It will take years for the picture to emerge.”

“Her trees are far more social than even Patricia suspected. There are no individuals. There aren’t even separate species. Everything in the forest is the forest. Competition is not separable from endless flavors of cooperation. Trees fight no more than do the leaves on a single tree.”

“She sees it in one great glimpse of flashing gold: trees and humans, at war over the land and water and atmosphere. And she can hear, louder than the quaking leaves, which side will lose by winning.”

The book draws on the latest discoveries about the nature of forests, as explained in Suzanne Simard’s TED talk about the Wood Wide Web. As with so many miracles of life on earth, we are discovering just how amazing a natural phenomenon is, just as we bring it to the brink of extinction. We lose one percent of the world forest every decade, which equates to an area larger than Connecticut, every year. Views vary as to how much old growth forest is left (according to Tree Sisters it is probably about 20%) but what we can be sure of is that we would be reckless to cut any more of it. Complex ecosystems like this take centuries to develop, so thinking that replanting is the same as replacing is, as The Overstory says, like arranging Beethoven’s Ninth for solo kazoo.

The book draws on the latest discoveries about the nature of forests, as explained in Suzanne Simard’s TED talk about the Wood Wide Web. As with so many miracles of life on earth, we are discovering just how amazing a natural phenomenon is, just as we bring it to the brink of extinction. We lose one percent of the world forest every decade, which equates to an area larger than Connecticut, every year. Views vary as to how much old growth forest is left (according to Tree Sisters it is probably about 20%) but what we can be sure of is that we would be reckless to cut any more of it. Complex ecosystems like this take centuries to develop, so thinking that replanting is the same as replacing is, as The Overstory says, like arranging Beethoven’s Ninth for solo kazoo.

The book urges us not to suffer from the bystander effect, allowing these sacrileges to happen on our watch, just because we didn’t see other people rushing to defend the trees. When we diminish our web of life, we diminish ourselves. If a forest can be, in effect, a single organism, then it doesn’t seem too much of a stretch to suggest that the very Earth itself is also a Gaia-type holistic system in which everything is connected – and that includes the humans.

In line with that thought, I’ll finish with a line from the book that sounds like a Zen koan:

“Who does the tree-hugger really hug, when he hugs a tree?”

Footnotes:

Julia Butterfly Hill

Julia Butterfly HillPlease see also the inspiring autobiography, The Legacy of Luna, by Julia Butterfly Hill, who sat in a redwood tree for 738 days and I’m sure was the inspiration for the Overstory character of Maidenhair.

And check out the amazing work being done by Tree Sisters (not to be confused with The Sisters – our new website is launching soon!).

See also Paul Hawken’s book, Drawdown, which quantifies the impact of forest protection on CO2 levels: “more than 15 billion [trees] are cut down each year. Since humans began farming, the number of trees on earth has fallen by 46 percent. Carbon emissions from deforestation and associated land use change are estimated to be 10 to 15 percent of the world’s total… By protecting an additional 687 million acres of forest, this solution could avoid carbon dioxide emissions totaling 6.2 gigatons by 2050. Perhaps more importantly, this solution could bring the total protected forest area to almost 2.3 billion acres, securing an estimated protected stock of 245 gigatons of carbon, roughly equivalent to over 895 gigatons of carbon dioxide if released into the atmosphere.”

Other Stuff:

Last week I was at the Klosters Forum in Switzerland for a 3-day conference on plastic pollution in the oceans. We had an intense series of workshops to explore ways to move towards zero plastic escaping into the environment. Great to see this important issue getting the attention it deserves!

Next week I’m off to Mystery of the Mountains to talk about my ocean rowing adventures. If you happen to be in the Dolomites that week, I’d love to see you there!

July 19, 2018

Possible Worlds

“The most wonderful and the most terrible of futures that have ever been possible are now possible.”

— First speaker at Bretton Woods

Last week’s Bretton Woods conference was intriguing, possibly raising more questions than it answered. Lots still to process, but I wanted to share one initial exchange that struck me powerfully.

I won’t name names, as it was Chatham House rules, so let’s simply call him our first speaker – he spoke primarily about the existential risk facing humans. He pointed out that throughout history, every developed society has collapsed. What is different now is that we don’t have a multiplicity of diverse societies, we have one globally interconnected society. Our current rivalrous game dynamics, multiplied by exponential technology will lead almost inevitably to our self-termination.

So that was cheerful – not. But it was going to get worse.

The second speaker set out his worst case scenario, which was a world in which humans have not been stopped by any of the existential threats, but have gone on to create a world in which all ecosystem services (also known as “nature”) have been replaced by manmade systems, so that our world becomes nothing but a strip mine alongside a waste dump. (He added, ironically, that our global GDP would still be looking just great, thank you.)

One brighter note from the same session suggested that, due to the theoretical phenomenon of morphic resonance, every single thing we do makes a difference – even our thoughts. The concept is that our thoughts, words, and actions contribute in some sense to the collective memory. So even just by caring about a thriving future, we are supporting its creation.

There again, creating the structures and systems – economic, governmental, and social – that support that thriving future, would be good too.

July 5, 2018

A New Bretton Woods

Next week I shall be traveling to Bretton Woods in New Hampshire for an event called the Global Economic Visioning. The event is actually a precursor to a larger event next year, on what will be the 75th anniversary of the original Bretton Woods conference.

Back in 1944, the first Bretton Woods was a gathering of 730 delegates from the 44 Allied Nations. It was towards the end of World War II, and the most pressing issues of the day were how to prevent a recurrence of the Great Depression, and to prevent another world war, which had in part arisen out of the economic misery in Germany and Japan which had provided fertile ground for fascist ideas to take root.

To this end, they set up the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). John Maynard Keynes, the key figure at the conference, argued that the rise of protectionism across the industrialised world had contributed to low aggregate demand: people weren’t buying enough stuff because prices were too high, and the economy had ground to a halt. For Keynes, excess protectionism was a primary driver of the Great Depression, so the goal of the GATT was to reduce tariffs across the board in order to boost demand.

To this end, they set up the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). John Maynard Keynes, the key figure at the conference, argued that the rise of protectionism across the industrialised world had contributed to low aggregate demand: people weren’t buying enough stuff because prices were too high, and the economy had ground to a halt. For Keynes, excess protectionism was a primary driver of the Great Depression, so the goal of the GATT was to reduce tariffs across the board in order to boost demand.

In other words, the GATT began its life as an ostensibly benevolent institution, intended to promote economic stability and peace. Just like the original IMF and the World Bank, which were founded during the same conference, it was rooted in Keynesian principles and intended to contribute to the collective good.

So the original Bretton Woods conference, and the institutions that it established, were products of their times. Now times have changed, as have the institutions that were established back in 1944. The World Trade Organisation, created in 1995, has usurped much of the power of the GATT, and free trade reforms have dismantled many of the capital controls that were intended to protect the stability of national economies. Investors can now withdraw their capital at short notice from a particular country if they think they can get a better return elsewhere, and if several investors do this at once, it can leave a country’s economy decimated.

Bretton Woods

Bretton WoodsFor several decades now, there have been increasingly loud calls for a new Bretton Woods, particularly to create a new international framework to tackle the problems of unfettered capital flows creating global financial crises, imbalances of access to capital between nations, and the exclusion of various constituents from economic progress and political participation. The conference of 2019 is described thus:

“By resetting the table of who is present and introducing the many technologies now available, this event will serve as a jumping off point for visioning an economic future that reflects the immense potential of all parts of our collective human society.”

This all sounds very promising, and I’d like to go even further. For sure, new technologies like blockchain have enabled possibilities impossible to imagine in 1944. And now we have a greater appreciation of the benefits of inclusivity and diversity.

And even more than that, we need to step outside our current story, and take a long, hard look at our global economic system from the outside. We created the economy, and while it has brought many benefits, in its current form it is also encouraging the destruction of our ecosystem and the widening gulf of global inequality. My sense is that we need to create a vision of where we want to be 75 years from now – for example, a world of peace, sustainability, and fairness sounds good to me – and work backwards from there to figure out what principles and structures will support that vision.

And even more than that, we need to step outside our current story, and take a long, hard look at our global economic system from the outside. We created the economy, and while it has brought many benefits, in its current form it is also encouraging the destruction of our ecosystem and the widening gulf of global inequality. My sense is that we need to create a vision of where we want to be 75 years from now – for example, a world of peace, sustainability, and fairness sounds good to me – and work backwards from there to figure out what principles and structures will support that vision.

To use a good ocean rowing analogy, we need to choose our destination, chart our passage, and determine our waypoints. Then we need to decide what kind of boat, or boats, are most likely to get us safely to where we want to be. And we need to choose the right metric to measure our progress – GDP is almost certainly not it.

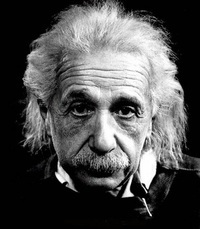

The prospectus for the Global Economic Visioning includes my favourite Einstein quote, that “We cannot solve our problems with the same level of thinking that created them.”

Amen to that, Einstein.

Quotes by John Maynard Keynes:

In the long run we are all dead.

The market can stay irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.

Words ought to be a little wild, for they are the assault of thoughts on the unthinking.

Capitalism is the astounding belief that the most wickedest of men will do the most wickedest of things for the greatest good of everyone.

Education: the inculcation of the incomprehensible into the indifferent by the incompetent.

Ideas shape the course of history.

If economists could manage to get themselves thought of as humble, competent people on a level with dentists, that would be splendid.

Other Stuff:

I very much enjoyed having this conversation with Nicole Haack in Australia for the Message Pod. I hope you enjoy it too!

June 28, 2018

Of Grabbing and Gifting

I’ve read two very contrasting books this week, The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, and Walk Out Walk On: A Learning Journey into Communities Daring to Live the Future Now.

I haven’t yet finished The Divide, so I’ve been wading through a whole load of inequality and haven’t got to the solutions part yet, but the earlier parts of the book about how we ended up in such an unequal world are shocking in an invigorating kind of a way. The author, Jason Hickel, is originally from Swaziland, so has experienced what it is like to live in the global South. His main contention is that the widespread poverty in the South is not a natural problem, it is a political problem.

The problems that have plagued Africa, South America, and large parts of Asia, are not due to any lack of the ability of its people to farm and govern effectively, but due to the rapacious behaviour of Europeans and North Americans over the last 500 years. After the conquistadors and slave traders came the governments and corporations that have conspired (in the most criminal sense of the word) to keep the South disempowered and downtrodden.

Some snippets:

Jason Hickel

Jason Hickel“In the year 1500, there was no appreciable difference in incomes and living standards between Europe and the rest of the world. Indeed, we know that people in some regions of the global South were a good deal better off than their counterparts in Europe. And yet their fortunes changed dramatically over the intervening centuries…”

“Why were AIDS patients dying? Over time, I learned that it had to do with the fact that pharmaceutical companies refused to allow Swaziland to import generic versions of patented life-saving medicines, keeping prices way out of reach. Why were farmers unable to make a living off the land? I discovered that it was related to the subsidised foods that were flooding in from the US and the EU, which undercut local agriculture. And why was the government unable to provide basic social services? Because it was buried under a pile of foreign debt and had been forced by Western banks to cut social spending in order to prioritise repayment…”

“Take hunger, for example. In 1974, at the first UN Food Summit in Rome, US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger famously promised that hunger would be eradicated within a decade. At the time there were an estimated 460 million hungry people in the world. But instead of disappearing, hunger got steadily worse. Today there are about 800 million hungry people, even according to the most conservative measures. More realistic estimates put the figure at around 2 billion – nearly a third of all humanity…”

He shows in great detail how UN or World Bank figures have been massaged to show apparent improvement in the plight of the world’s poor, when in fact their situation has got worse. For example:

“The standard poverty measure counts the number of people who live on less than a dollar a day. But in many global South countries a dollar a day is simply not adequate for human existence, to say nothing of human dignity. Many scholars are now saying that people need about four times that in order to have a decent shot at surviving until their fifth birthday, having enough food to eat and reaching normal life expectancy. So what would happen if we measured global poverty at this more realistic level? We would see a total poverty headcount of about 4.3 billion people.”

Hickel’s version of history focuses on colonialism, in which precious metals, minerals, and people were extracted from the South and exploited to serve the economic fortunes of the North. After slavery was abolished and colonialism was drawing to a close, third world debt became the new weapon of mass destruction: during the 1970s there was effectively a sub-prime boom in loans to southern countries, which due to high rates of compound interest became a kind of economic slavery. Democratically elected leaders who showed signs of raising their countries out of poverty were removed by coup or by assassination, orchestrated from the north, and replaced with dictators friendly to northern economic agendas.

But hang on, you might be thinking. Don’t we in the north send lots of aid overseas? Surely we’re the good guys!

Here’s what Hickel has to say about that:

“The US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) and the Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics published some truly paradigm-shifting data. They tallied up all of the financial resources that get transferred between rich and poor countries each year: not just aid, foreign investment and trade flows, as previous studies have done, but also other transfers like debt cancellation and remittances and capital flight. It is the most comprehensive assessment of resource transfers that has ever been made. They found that in 2012, the last year of recorded data, developing countries received a little over $2 trillion, including all aid, investment and income from abroad. But more than twice that amount, some $5 trillion, flowed out of them in the same year. In other words, developing countries ‘sent’ $3 trillion more to the rest of the world than they received. If we look at all years since 1980, these net outflows add up to an eye-popping total of $26.5 trillion – that’s how much money has been drained out of the global South over the past few decades… Since 1980, developing countries have forked over $4.2 trillion in interest payments – much more than they have received in aid during the same period.”

“The US-based Global Financial Integrity (GFI) and the Centre for Applied Research at the Norwegian School of Economics published some truly paradigm-shifting data. They tallied up all of the financial resources that get transferred between rich and poor countries each year: not just aid, foreign investment and trade flows, as previous studies have done, but also other transfers like debt cancellation and remittances and capital flight. It is the most comprehensive assessment of resource transfers that has ever been made. They found that in 2012, the last year of recorded data, developing countries received a little over $2 trillion, including all aid, investment and income from abroad. But more than twice that amount, some $5 trillion, flowed out of them in the same year. In other words, developing countries ‘sent’ $3 trillion more to the rest of the world than they received. If we look at all years since 1980, these net outflows add up to an eye-popping total of $26.5 trillion – that’s how much money has been drained out of the global South over the past few decades… Since 1980, developing countries have forked over $4.2 trillion in interest payments – much more than they have received in aid during the same period.”

The whole book is packed with facts that made my jaw drop. I can only offer a tiny taster here. I do recommend the book in its entirety.

It may, however, be rather depressing and guilt-inducing, especially if, like me, you are a comparatively privileged, racial majority person living in the global North. (Okay, so I’m half South African, but to look at me it’s entirely obvious that I’m talking white South African, so if anything that increases my ancestral guilt, rather than alleviating it.)

So if you need some cheering up after all that, I’d suggest you get out there and do something to make the world a better place (e.g. by supporting Kiva.org, or The Sisters).

And/or read Walk Out Walk On, by Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze. I had the privilege of a conversation with Deborah a couple of days ago.

Deborah Frieze

Deborah FriezeThe book is a celebration of people who choose not to be victims of their circumstances, but to become leaders who help guide their communities towards a better world.

“Inside dying systems, Walk Outs Who Walk On are those few leaders who refuse to work from the dominant values that permeate the bureaucracy, such things as speed, greed, fear, and aggression. They use their formal leadership to champion values and practices that respect people, that rely on people’s inherent motivation, creativity, and caring to get quality work done.”

These leaders walk out of the system that’s not working, and walk on to create a new system that does.

The authors look at seven projects happening in seven very different locations, in Mexico, Zimbabe, Brazil, South Africa, India, Greece and…. Ohio, in which people are taking back their power and transforming their communities. Their stories are inspiring and hopeful.

I believe that this is the future – walk-outs coming together and empowering themselves to create sustainable transformation.

The Divide reflects on 500 years of dominator-model grabbing – land grabs, resource grabs, power grabs (and we know what the current US president likes to grab). I’m sure, when you were little, you were probably told – as I was – that it’s not nice to grab, you have to share. I’d like to think that we are moving into a more mature stage in human development, where we evolve into sharing our gifts for the greater good of all.

June 21, 2018

Of Plutocrats and Pitchforks

“The greatest country, the richest country, is not that which has the most capitalists, monopolists, immense grabbings, vast fortunes, with its sad, sad soil of extreme, degrading, damning poverty, but the land in which there are the most homesteads, freeholds – where wealth does not show such contrasts high and low, where all men have enough – a modest living- and no man is made possessor beyond the sane and beautiful necessities.”

Walt Whitman

Recently I was on a retreat weekend with sixteen women. One of us, Alex, led an exercise that still gives me pause for thought. She handed out one playing card to each of us. We weren’t to look at our own card, but were to place it against our forehead with the number side facing outwards so others could see it. We then had 5 minutes to interact with each other, and we had to behave according to the denomination of the other woman’s card.

So if she was holding an ace, king or queen, we were to treat her as an important person worthy of respect and esteem. If she was holding a two or a three, we were to treat her as the lowest of the low. At the end of the 5 minutes, still without looking at our own card, we had to line up according to where we thought we lay in the social order, from high to low. We succeeded with an uncanny degree of accuracy.

Here were some interesting things I noticed.

The high-ups pretty quickly started acting entitled, even though the cards had been handed out at random.

The high-ups pretty quickly started acting entitled, even though the cards had been handed out at random.The low-downs were initially subservient, but it wasn’t long before we (yes, I was a lowly three) were banding together and plotting to overthrow the upper classes.

We were finely sensitive to how we were being treated, and knew exactly where we stood.

It was almost scary how, regardless of our real life circumstances, and with no special acting abilities, we easily slipped into role as a high-up or a low-down.

It definitely felt better to be an ace or a king than a two or a three.

So what does this say about real life, where some people are handed a high card at birth, while the majority are handed low cards? Of course, there are still some self-made people, but increasingly wealth is inherited. (See Capital, by Thomas Piketty.)

Global wealth increased by £7.3 trillion in the year up to June 2018. More than 80 per cent of this new prosperity was enjoyed by the top one per cent of the population. Meanwhile, the poorest half got no increase.

There is ample research to back up the theory that rich people are more likely to act like jerks and less likely to have empathy. I recommend this TED talk by Paul Piff. (This does make you wonder how empathic a cabinet worth a collective $4.3 billion can be.)

Marie Antoinette (while she still had her head)

Marie Antoinette (while she still had her head)Nick Hanauer, himself a rich guy, warns his fellow plutocrats: “Beware, the pitchforks are coming”, because massive inequalities have historically never been sustainable. Just ask Marie Antoinette.

But are the pitchforks coming? (Not that I’m for a moment advocating pitchforks.) It seems that – at least as far as I can tell from spending most of my time in the UK and the US – that many of those who were handed low cards are less likely to get angry at the abuse of privilege at the top, and more likely to turn to the modern-day opiate of the masses – shopping.

This article in The Guardian states that: “Studies have shown that conspicuous consumption is intensified by inequality. If you live in a more unequal area, you are more likely to spend money on a flashy car and shop for status goods. The strength of this effect on consumption can be seen in the tendency for inequality to drive up levels of personal debt as people try to enhance their status.”

The average US household is carrying $16,000 in credit card debt. In the UK it’s £8,000 per person. There are probably many with no such debt at all, meaning that some have dramatically more debt.

And that debt leads to problems. From the Guardian article again: “The gap between image and reality yawns ever wider. Our rich society is full of people presenting happy smiling faces both in person and online, but when the Mental Health Foundation (in the UK) commissioned a large survey last year, it found that 74% of adults were so stressed they felt overwhelmed or unable to cope. Almost a third had had suicidal thoughts and 16% had self-harmed at some time in their lives. The figures were higher for women than men, and substantially higher for young adults than for older age groups. And rather than getting better, the long-term trends in anxiety and mental illness are upwards.” I’d be curious to know how much of that anxiety is due to financial worries.

Depressed and anxious people don’t tend to reach for their pitchforks. They withdraw from society and self-medicate with alcohol, TV, and video games. Never before have there been so many ways to distract ourselves from harsh reality.

So how do we fix it? This article in the New Statesman calls for: “A genuine shared future means building an economy that works directly to end poverty, not one that hopes for it as a side-effect of growth” – which all sounds very good, but if the peasants aren’t revolting, why would governments bother to take up on the massively unpopular task (particularly unpopular with their donors) of redistributing wealth from rich to poor? Especially when they have more pressing issues like Brexit or North Korea to deal with?

So maybe it is the task of Margaret Mead’s small group of thoughtful, committed citizens to start the change. Are you one of us?

“On Earth… you do not think there is enough for everyone, and so you have to make sure that you get yours. It is the idea of scarcity that stifles the idea of full and complete sharing… What your planet could benefit from right now are a few more humans willing to demonstrate and model a new form that humanity could take, based on their belief in Sufficiency and Sharing, and in this way helping to awaken the species. These models will have to self-select, however, because no one is going to appoint or anoint them.

Neale Donald Walsch, Conversations with God

June 14, 2018

Mother Nature and Father Greed

“There is only one force bigger than Mother Nature, and that is Father Greed.”

Thomas Friedman

Thomas FriedmanSo writes the Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Thomas Friedman. He’s concerned, rightly, at our lack of progress on the United Nation’s 2030 Global Goals, so is suggesting in this interview with The Sustainian that politicians can spark massive investment in sustainability by leveraging corporate greed.

“The next great global industry has to be clean energy, clean water and energy efficiency, otherwise, we are going to be a bad biological experiment.”

I’d love to know how that idea is landing with you right now. Does it seem like a sensible, pragmatic plan to incentivise change? Does it fill you with revulsion? Or somewhere in between?

Myself, I’m somewhere in between, but leaning somewhat towards the revulsion end of the spectrum.

As I wrote from the World Ocean Summit earlier this year, I’m with Einstein on the dictum that “No problem can be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it”. There again, the shift in consciousness is proving to be a perilously long time in coming.

I’m reminded of a workshop I attended five or six years ago (which obviously had a big impact on me, because my memory isn’t usually this good). It was about values and frames, and was run by Common Cause. As we arrived in the morning, we were asked what we thought were the biggest challenges facing the world. Our answers were compiled on a flipchart. Once we were all seated, we were asked to look at a chart of 57 values, and put marks next to the ones that we thought would be most useful, and the least useful, in addressing those challenges. (More information about Shalom Schwartz’s basic human values research here.)

Our consensus, which is borne out by the research, was that the most constructive values were intrinsic values, broadly classed as benevolence and universalism. The least useful values were extrinsic values such as hedonism, achievement, and power.

Our consensus, which is borne out by the research, was that the most constructive values were intrinsic values, broadly classed as benevolence and universalism. The least useful values were extrinsic values such as hedonism, achievement, and power.

Further, we were warned about appealing to extrinsic values in order to trigger “good” behaviours. Rewards, incentives, and bribes were considered to be at best successful in the short term only (as parents of small children may attest), and at worst to condition people to expect rewards for actions that should be internally motivated.

This ties in with research by Barry Schwartz (no relation of Shalom, as far as I’m aware) on Why We Work, which is summarised by the wonderful Maria Popova in her Brainpickings article, which I highly recommend:

“When we lose confidence that people have the will to do the right thing, and we turn to incentives, we find that we get what we pay for… There is really no substitute for the integrity that inspires people to do good work because they want to do good work. And the more we rely on incentives as substitutes for integrity, the more we will need to rely on them as substitutes for integrity. We may tell ourselves that all we’re doing with our incentives is taking advantage of what we know about human nature… But in fact, what we’re doing is changing human nature. And we’re not merely changing it; we’re impoverishing it.”

What Schwartz suggests is that the best motivation is based not on reward and punishment but on what Adam Smith called the “impartial spectator” — an imaginary figure who evaluates the morality of our actions objectively and to whom we hold ourselves accountable, our own internal Jiminy Cricket.

So at this point it looks as if we are straying into dangerous territory if we try to get people to do the right things for the wrong reasons.

But are we assuming that all people are the same? Could it be that a more nuanced approach is possible?

Chris Rose

Chris RoseIn How to Win Campaigns (a refreshingly self-explanatory title), Chris Rose tells us that there are three kinds of people in the world (or at least in the UK):

Settlers (31%): motivated by resources and by fear of perceived threats. They tend to be older, socially conservative and security conscious. They are often pessimistic about the future, and are driven by immediate, local issues affecting them and their family (and probably voted for Brexit).

Prospectors (37%): Driven by the esteem of others. They are motivated by success, status and recognition. They are usually younger and more optimistic. They are often conscious of fashion or image, and tend to be swing voters.

Pioneers (32%): Motivated by self-realisation. Their views are governed by values of collectivism and fairness. In their personal lives they are ambitious, but seek internal fulfilment rather than the esteem of others.

(More about these Values Modes here. And for the campaigners reading this, I highly recommend Chris’s books, and there are also oodles of information on his Campaign Strategy website.)

So we can imagine that a Pioneer would, and should, not be moved by external incentives. But a Prospector might, if it made them look good. And a Settler would be more likely to be influenced by issues affecting their family and community than by anything Thomas Friedman or the UN might have to say. So arguably there is a role for external motivations, even if they only work for slightly over a third of the population.

So we can imagine that a Pioneer would, and should, not be moved by external incentives. But a Prospector might, if it made them look good. And a Settler would be more likely to be influenced by issues affecting their family and community than by anything Thomas Friedman or the UN might have to say. So arguably there is a role for external motivations, even if they only work for slightly over a third of the population.

To return to Friedman, I wonder if he would respond by saying I’m creating a straw man argument, that he was talking about appealing to the greed of corporations, not individuals, which are not the same thing (no matter what US law may say on the matter), and that because corporations have a profit motive, they are not so much the sum of their parts, as a completely different kind of organism that is and should be motivated by greed. But then are we in danger of reversing the encouraging trend towards the idea that companies can do well by doing good?

There are implications for complementary currencies like the forthcoming app, Dashboard.earth, that “rewards” environmentally beneficial behaviour with points that can be redeemed at participating businesses. Even in the yin currency of Bali, with its element of ostracization if a family does not fulfil its pledge of time and/or money to support a community project – is this not also extrinsic motivation?

I’m going to leave the final word to Neale Donald Walsch, author of Conversations with God. Last week, in my blog post on Yin, Yang, and Jung, I shared the idea that because our financial systems have buried the Great Mother archetype representing abundance, we have ended up with its shadows, greed (see above) and scarcity.

NDW writes: “The reason that you do not behave this way on Earth is that you do not think there is enough for everyone, and so you have to make sure that you get yours. It is the idea of scarcity that stifles the idea of full and complete sharing. What your planet could benefit from right now are a few more humans willing to demonstrate and model a new form that humanity could take, based on their belief in Sufficiency and Sharing, and in this way helping to awaken the species.”

I’d love to hear your thoughts on this. Should we be taking a “whatever it takes” approach to motivating behaviour change? Or should we be holding out for a shift in consciousness? Or a blend of both?

Other Stuff:

I’m delighted to have been invited to a Global Economic Visioning summit in New Hampshire next month. It’s wonderful to know that these topics I’ve been thinking about are gaining traction and importance. I’m sure it will be a fascinating three days!