Roz Savage's Blog, page 18

September 5, 2019

Of Waves and Wonderings

Here’s something I have been thinking about, and I thought it would be interesting to run it past you, my dear readers….

Wilderness and spirituality have long been linked. Jesus went out into the desert for forty days and forty nights. Moses went up a mountain. The Buddha sat under a tree. Thoreau went to the woods. Tenzin Palmo went to a cave in the snow. Michael Crichton (of Jurassic Park fame) talked to a cactus.

Note: none of them sat in an office, on their sofa at home, or even on a meditation cushion (although Tenzin probably did a fair bit of that too).

There was something about being in nature that opened them up to wisdom in a way that manmade environments didn’t. I’m not saying for a moment that it’s impossible to find spiritual insight in cities – maybe just that it’s harder.

I certainly hoped to find enlightenment on the ocean. As it turned out, this was challenging. There were a lot of distractions, like stuff breaking, getting blown off course, getting injured, and so on. My emotions veered between boredom and terror, with not that much in between. Serenity and insight seemed extremely distant, most of the time. As it was happening, the experience seemed anything but spiritual.

However, in hindsight, I wonder….

It took me ten years to discover the perfection in everything that went wrong. If everything had gone perfectly smoothly and according to plan, I would not have learned anywhere near as much as I did, conquered my fears and my inner demons (mostly), and grown as much as a person. It took a hostile environment like the ocean (hostile to humans, anyway) to humble me, strip away my ego, at times even make me just about forget who I was, other than a puny rower struggling her way across a vast ocean.

But I also wonder if there is something symbolic about oceans, that I am only just starting to understand and appreciate. These thoughts have been brought on in part by my current reading matter – I’ve just finished Saltwater Buddha: A Surfers Quest to Find Zen on the Sea, by Jaimal Yogis, and have started his second memoir, All Our Waves Are Water: Stumbling Towards Enlightenment and the Perfect Ride. He writes a lot about how surfing has illustrated and amplified his understanding of Buddhism and life in general.

Jaimal Yogis

Jaimal YogisOf course, there is wisdom and learning to be found in any kind of activity. It’s not what you do, it’s the way that you do it – mindfully or otherwise. I simply feel that some activities have more metaphorical value than others – for example, surfing seems more conducive to insight than playing video games.

And is there also something about the ocean as a symbol for the ineffable, the real-but-unseen that hides in plain sight all around us? In Jungian therapy, oceans and other large bodies of water symbolise the unconscious. It can also represent the beginning of life on Earth, and formlessness, the unfathomable, and chaos. There is something primal, ancient, and deeply mysterious about it.

From my low vantage point on the boat, I could see the surface of the ocean, the appearance of which depended mostly on how much wind was disturbing its surface, and what colour it was reflecting from the sky. So what I was seeing was the superficial perturbation of the ocean, not really the ocean itself. Of course, I knew that there was a whole load of ocean down there, averaging around two miles in depth, and covering huge swathes of the Earth’s surface. But I mostly couldn’t see it – couldn’t see what creatures lurked unless they chose to break the surface, couldn’t see how much plastic was distributed throughout the water column, couldn’t see into the inky depths, couldn’t see the ocean floor. I could see the “face” of the ocean, but that was only a tiny fraction of its totality and reality.

Arguably, the same could be said of the workings of our own inner selves, which remain largely unknown and unknowable to us. We see our surfaces, as they react to the winds and the weather of our daily lives, but the surface should not be mistaken for the totality and the reality of who we are.

I very much like the way that Jaimal describes individual humans as being like waves on the ocean of consciousness. I’d come across the analogy before, and it really resonates with me. No matter how they appear (or, in my experience, how they feel when they hit you!), waves are not actually moving chunks of water. A water molecule does not go waving its way across an ocean. Rather, waves are a chain reaction of energy being passed from one water molecule to the molecule next to it. This creates:

“the illusion of a fixed entity, a “wave” made of water, which has travelled miles to its destination. But really, the wave is a domino effect of energy, a series of causes and conditions. In essence, the wave is the memory of wind energy transferring between water molecules. Very little water is actually moving. A wave is at once real (real enough to pound rocks to sand) and completely different in every second. Though the wave is definitely real, and appears solid, it is also something of an illusion. (Jumping ahead a little bit, I could also add that our bodies are like these waves, as the molecules that make them up constantly shift and change over time —and the idea that there’s a single solid and persisting entity called “me” is a similar illusion.)”

We live in a culture (neoliberal, consumerist) where the concept of “me”-ness is very strong. We see ourselves as individual, isolated blobs of consciousness with our own unique identity, to which we become quite attached. Some of us believe that this unique identity even goes on after our body dies, into an eternal afterlife. We believe that I am a “human”, that creature is a “squirrel”, that thing is a “tree”, and that thing is a “rock” or a “star”, all separate and discrete. But what if I understood if the only thing that separated “me” from all of “those” was time? What if I knew that the molecules that make up the wave of existence currently called Rosalind Savage would one day get reassigned to become squirrels and trees and rocks and stars, just as they have been assigned in the past? Would that understanding make any difference to the way I treat those non-me molecules in their present incarnation?

Maybe, maybe not. Just wondering… What do you think?

August 29, 2019

The Meaning of Life

Wow, that is quite a presumptuous title for a blog post! The meaning of life, in 750 words or less…

I’m taking a break from talking about my doctorate to share a cascade of hypnopompic insight that emerged as I woke up this morning, probably inspired by listening to Pema Chodron’s When Things Fall Apart during a long drive yesterday.

As you might expect from someone who changed the course of her life after writing her own obituary, I’ve thought a lot about why we’re here. Is there any “why” at all, or do we just get born, live, die, game over? Does it matter what we do while we’re alive – matter to us and/or to anybody else? If we assume that we should do our best to live a “good” life, what does that even mean? Good according to whom – our fellow humans, ourselves, a judgemental God who sits like a cosmic Santa Claus to decide if we’ve been a good enough girl or boy in this lifetime to deserve the ultimate Christmas gift of everlasting life?

As you might expect from someone who changed the course of her life after writing her own obituary, I’ve thought a lot about why we’re here. Is there any “why” at all, or do we just get born, live, die, game over? Does it matter what we do while we’re alive – matter to us and/or to anybody else? If we assume that we should do our best to live a “good” life, what does that even mean? Good according to whom – our fellow humans, ourselves, a judgemental God who sits like a cosmic Santa Claus to decide if we’ve been a good enough girl or boy in this lifetime to deserve the ultimate Christmas gift of everlasting life?

Hunter S Thompson, the founder of the gonzo journalism movement, decreed that, “Life should not be a journey to the grave with the intention of arriving safely in a pretty and well preserved body, but rather to skid in broadside in a cloud of smoke, thoroughly used up, totally worn out, and loudly proclaiming “Wow! What a Ride!”” *

I’m not sure I would go that far, but my very personal view (and I am open to other people having different views) is that human life is meant to be lived richly, in all its messy, glorious variety.

When I wrote my fantasy obituary in the late 1990s, I was inspired by the obits I’d read in the newspaper, particularly those of colourful characters who seemed to have lived many different lifetimes in one, reinventing themselves several times over. They had really got out there and lived the heck out of life.

This idea was reinforced a few years later when I read Conversations with God (Book 3), by Neale Donald Walsch. Speaking as God, he says:

[My] purpose is for Me to create and experience Who I Am through you, lifetime after lifetime, and through the millions of other creatures of consciousness I have placed in the universe… So, your purpose as a soul is to experience yourself as All Of It. We are evolving. We are becoming… Consciousness is a marvellous thing. It can be divided into a thousand pieces. A million. A million times a million. I have divided Myself into an infinite number of ‘pieces’ – so that each ‘piece’ of Me could look back on Itself and behold the wonder of Who and What I Am.

Barbara Marx Hubbard writes in the same vein:

“Whatever we are going through is part of the planetary struggle to evolve.”

Around the same time as Conversations with God, I read Hidden Journey by Andrew Harvey, here quoting what a friend told him about how best to serve their guru, Ma:

To be of use to Ma, you must know everything about your own nature; to do her work, you must have truly understood the world, not fled from it. Ma wants people to be juicy… full of passion and humour, truly human…

Michael Singer taps into this same thread in The Surrender Experiment, in which he recounts the story of his transition from meditator and teacher, to construction company founder, to tech founder, encountering dizzying heights and heartbreaking lows along the way:

“My formula for success was very simple: Do whatever is put in front of you with all your heart and soul without regard for personal results. Do the work as though it were given to you by the universe itself – because it was.”

Beau Lotto in Deviate talks about how we can help our brains become better wired for creativity when we embrace challenge and novelty, uncomfortable as that might be:

“you must constantly step into an emotionally challenging place and experience difference…actively!…actively seeking contrast is the engine that drives change (and the brain)”

Coming back to Pema Chodron, she talks about the eight worldly dharmas of pleasure and pain, loss and gain, praise and blame, fame and disgrace. As humans, we think we want just the pleasure, the gain, the praise and the fame, but those things can’t exist without the pain, loss, blame, and disgrace. We judge some things as “good” and some as “bad”, but actually they’re all a necessary part of the human experience, and paradoxically we cause ourselves all sorts of anxiety and suffering by trying to avoid the parts we have labelled “bad”.

“Letting there be room for not knowing is the most important thing of all. When there’s a big disappointment, we don’t know if that’s the end of the story. It may just be the beginning of a great adventure. Life is like that. We don’t know anything. We call something bad; we call it good. But really we just don’t know.”

So the point I take away from all of these great thinkers is that our main job in this lifetime is not to seek security, but rather to embrace challenges as an opportunity for growth. It is important that we create safety for our children while they are young, but primarily so that they have the emotional foundation of confidence that will later enable them to explore more boldly, rather than to trying to insulate them from the challenges of life.

Once we’re grown, and especially in these fast-changing times, we need to let go of the shore and surrender to the fast-running currents in the middle of the river. We seek to accept what life throws at us – “good” or “bad” – as being exactly what we need to encounter in order to evolve in this moment. If we try to avoid the pain, or take the edge off it through drugs or alcohol or busy-ness and distraction, we’re just postponing the learning and prolonging the agony. Better to dive into fully feeling what we’re feeling, and finding the gift in it. It’s all part of this amazing privilege of being human.

*Thompson himself went out with a bang – literally. Having often remarked: “I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone, but they’ve always worked for me”, he committed suicide at the age of 67 after a series of health problems. As per his wishes, his ashes were fired out of a cannon in a ceremony funded by his friend Johnny Depp and attended by John Kerry and Jack Nicholson.

August 21, 2019

The Shift in Consciousness (and what does that even mean?)

I expect there is a real danger in sharing these very preliminary drafts of my doctoral thesis, but heck, they may well change out of all recognition by the time I get to the final draft, so I could equally justify sharing them now because they may never see the light of day otherwise.

Anyhow, following on from last week, here some more vaguely DProf-related thoughts that I would like to share.

I have noticed, in various conversations both public and private, an emerging understanding that what is needed to create a more sustainable future is nothing short of a “shift in consciousness”. There is a danger, however, that this term is used as a shorthand for a concept that is rarely made explicit, and I have been as guilty of this as anybody. Given the enormous difficulty of even defining consciousness as a standalone concept, let alone a shift in consciousness, this enquiry could turn into a never-ending rabbit hole, but I think we can relatively easily find a definition that is sufficient to suit our purposes.

Donella Meadows, lead author of the Club of Rome-commissioned 1972 report, The Limits to Growth, drew on systems change theory to arrive at a list of the twelve most powerful leverage points in a system. Her full list, in increasing order of effectiveness is:

12. Constants, parameters, numbers (such as subsidies, taxes, standards).

11. The sizes of buffers and other stabilizing stocks, relative to their flows.

10. The structure of material stocks and flows (such as transport networks, population age structures).

9. The lengths of delays, relative to the rate of system change.

8. The strength of negative feedback loops, relative to the impacts they are trying to correct against.

7. The gain around driving positive feedback loops.

6. The structure of information flows (who does and does not have access to information).

5. The rules of the system (such as incentives, punishments, constraints).

4. The power to add, change, evolve, or self-organize system structure.

3. The goals of the system.

2. The mindset or paradigm out of which the system — its goals, structure, rules, delays, parameters — arises.

1. The power to transcend paradigms.

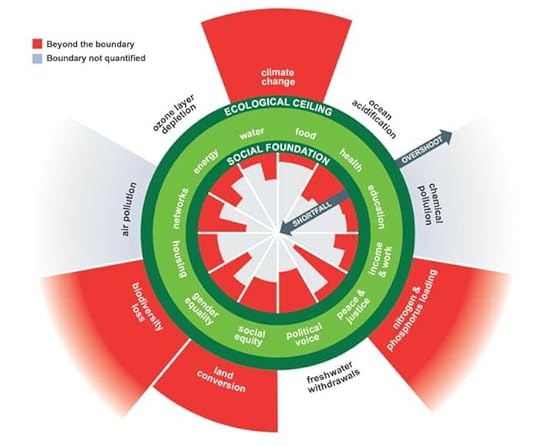

Here I am particularly interested in the top two, which I believe sum up the essence of a shift in consciousness. If “the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises” means the perception of reality that governs the way we organise our world, then if the way we organise our world is failing, we need to transcend that paradigm and find a better one. It is increasingly apparent that our current mindset/paradigm is not going to serve our long term needs as a species. Kate Raworth, who names Tim Jackson (Prosperity Without Growth) and Elinor Ostrom (Nobel Prize Winner for her work on the tragedy of the commons) as key influences (as they have been for me too), takes the nine planetary boundaries set out by Rockstrom et al, and identifies overshoot in four of them: climate change, biodiversity loss, land conversion, and nitrogen and phosphorus loading. Any of these in isolation would be serious; in combination, they are catastrophic. Our need for the power to transcend paradigms is urgent.

The reason that I am dwelling on the need for a new narrative of connection is that I believe that we need to rethink our worldview from this deep level in order to generate the shift in consciousness to support our transition from an ecologically destructive economic model to a regenerative one, and from a warlike domination-based society to a peaceful one centred on partnership. Only when we have institutional structures rooted in a narrative of humanity as part of an interconnected web of life, in which there is no “away”, and we co-exist in the closed loop system of Planet Earth, can we aspire to true sustainability.

As George Monbiot says in his 2019 TED Talk on the new political story that could change everything:

“Stories are the means by which we navigate the world. They allow us to interpret its complex and contradictory signals. When we want to make sense of something, the sense we seek is not scientific sense but narrative fidelity.”

He goes on to say that all the fundamental transformations in society have occurred when a new narrative came along that offered a more compelling and resonant interpretation of what was going on. When a narrative fails, as the neoliberal capitalist narrative has been failing since 2008, transformation cannot happen unless there is a new organising narrative, and so far that new narrative has failed to materialise. He proposes that what we need is a shift from the narrative of “extreme individualism and competition” to a narrative of “altruism and cooperation”.

Albert Einstein also spoke convincingly on this subject:

“A human being is part of the whole called by us universe … We experience ourselves, our thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest. A kind of optical delusion of consciousness. This delusion is a kind of prison for us, restricting us to our personal desires and to affection for a few persons nearest to us. Our task must be to free ourselves from the prison by widening our circle of compassion to embrace all living creatures and the whole of nature in its beauty. The true value of a human being is determined by the measure and the sense in which they have obtained liberation from the self. We shall require a substantially new manner of thinking if humanity is to survive.”

Likewise, the Buddhist scholar and creator of The Work That Reconnects, Joanna Macy:

“I consider that this shift [to an emphasis on our “capacity to identify with the larger collective of all beings” ] is essential to our survival at this point in history precisely because it can serve in lieu of morality and because moralising is ineffective. Sermons seldom hinder us from pursuing our self-interest, so we need to be a little more enlightened about what our self-interest is. It would not occur to me, for example, to exhort you to refrain from cutting off your leg. That wouldn’t occur to me or to you, because your leg is part of you. Well, so are the trees in the Amazon Basin; they are our external lungs. We are just beginning to wake up to that. We are gradually discovering that we are our world.”

And biologist Paul Ehrlich:

“The main hope for changing humanity’s present course may lie … in the development of a world view drawn partly from ecological principles – in the so-called deep ecology movement. The term ‘deep ecology’ was coined in 1972 by Arne Naess to contrast with the fight against pollution and resource depletion in developed countries, which he called ‘shallow ecology’. The deep ecology movement thinks today’s human thought patterns and social organisation are inadequate to deal with the population-resource-environmental crisis – a view with which I tend to agree. I am convinced that such a quasi-religious movement, one concerned with the need to change the values that now govern much of human activity, is essential to the persistence of our civilisation.”

Philosopher Arne Naess:

Philosopher Arne Naess:

“The ecosophical outlook is developed through an identification so deep that one’s own self is no longer adequately delimited by the personal ego or the organism. One experiences oneself to be a genuine part of all life .. We are not outside the rest of nature and therefore cannot do with is as we please without changing ourselves … Paleontology reveals .. that the development of life on earth is an integrated process, despite the steadily increasing diversity and complexity. The nature and limitation of this unity can be debated. Still, this is something basic. “Life is fundamentally one.””

So the idea of needing a new narrative that emphasises connection rather than separation is far from new. Both the Presencing approach and the Deep Ecology approach offer a worldview in which everything is connected so that damage inflicted on any aspect of the world impacts on the whole, including the one doing the damaging.

Why has it not yet caught on with a sufficiently large proportion of the population for it to become the dominant narrative in our culture?

Most people’s personal experience is based on having been enculturated into a worldview of separation. Arguably, it has been because the entire neoliberal/political apparatus, with all its power, that wants to maintain the status quo, and is heavily invested, both financially and culturally, in ensuring that human individuals remain isolated and locked in mutual competition. This is the narrative on which the neoliberal experiment depends, the narrative on which GDP as a measurement of success depends, and the narrative that is leading us towards ecological and social destruction.

So how do we change this narrative, when it is enshrined in every aspect of our white, western culture from media to politics to advertising to entertainment? The narrative that we so urgently need still lives on in the few tiny pockets of indigenous culture that we have allowed to survive, and we see the moral authority of the Native Americans taking a stance on issues like the Dakota Access Pipeline. But mostly we have rendered these groups voiceless and powerless, at the time when we need them most.

P.S. I feel that there is a shift taking place. It’s hard to quantify, and mostly anecdotal, based on my own experiences and conversations.

The question is, will the shift be big enough and fast enough to do what needs to be done?

August 14, 2019

A New Voyage of Discovery

I’ve mentioned a couple of times recently that I’ve started a doctorate at the University of Middlesex. I’ve wanted to do a doctorate for at least 7 years, and about once a year I would Google around and try to find something that matched my interests, and invariably failed. Then, by way of a friend of a friend, I found out about the Doctor of Professional Studies by Public Works. Essentially, I would be studying my own body of “public works” – defined widely enough to include ocean rowing voyages, TED Talks, books and blog posts – to critique them and place them in a wider intellectual context. So I would be exploring all the ideas that have caught my interest over the last 15 years. Perfect!

So here we are. I would like to share this journey with you over the coming months.

As anyone who has done a doctorate will know, the early drafts will bear little resemblance to the finished article, so please accept that fact and forgive. This may be terribly ill-advised of me to share my half-baked thoughts. There again, some of you have crossed three oceans with me, day by day, with the adventure unfolding as I went along.

I’d like to think we’re re-creating that vibe, in the context of an intellectual rather than a maritime journey.

And also, as you will know if you read my blog post the other week, I’m rather sceptical about the academic style of writing. There again, I may have to meet academia halfway and translate my thoughts into academic-ese. But for now I share in plain(ish) English. Here’s a short excerpt from what I’ve written so far.

There is a huge challenge inherent in attempting to fit one’s own life, with all of its messy interplay between rationality, intuition, and circumstance, into a tidy narrative that fits comfortably within the academic context. Inevitably, there is a certain amount of ex post facto rationalisation and interpretation, but this is a large component of the Doctorate of Professional Studies by Public Works; the bid to explain to oneself as well as to others why one has chosen to do what one did. Humans are meaning-making creatures; research has shown that the brain (or at least, the left hemisphere) prefers coherence over accuracy, and certainty over ambiguity. And so we endeavour to make meaning of our existence, even though our interpretation may not always chime with the thought processes that we were aware of at the time.

Spending extended periods, of up to five months continuously, in solitude, only exacerbates the challenge. I was the only witness to my experience, and although I have always tried to be truthful and accurate in my reporting, inevitably there is a certain amount of editing, distortion, and deletion. The blog posts that I wrote daily while at sea, along with the notes I wrote my logbooks at the end of each rowing shift, are the closest I have to original source material, and yet even they are only a very partial record of what actually took place. Countless thoughts and experiences arose and then vanished, as ephemeral as waves in an ocean.

Despite the inevitably flawed task of representing my public works as I perceived them at the time, I make no apologies for any inaccuracies or omissions. The main value in experiences is not so much what factually happened, but how we interpret and apply what transpired.

As an example of how this process operates, I would like to offer the moment when I “decided” to row across oceans, using my adventures to raise awareness of our environmental issues. The truth, as accurately as I can recall, was that for several months I had been sitting with the question of what I could do to help raise the alarm on our ecological crisis. Since my environmental epiphany, I had felt a strong sense of purpose and urgency, but had no idea how I could convert this impetus into an executable project. I knew what I wanted to achieve – raise awareness and inspire action – but couldn’t find a means to the end.

As an example of how this process operates, I would like to offer the moment when I “decided” to row across oceans, using my adventures to raise awareness of our environmental issues. The truth, as accurately as I can recall, was that for several months I had been sitting with the question of what I could do to help raise the alarm on our ecological crisis. Since my environmental epiphany, I had felt a strong sense of purpose and urgency, but had no idea how I could convert this impetus into an executable project. I knew what I wanted to achieve – raise awareness and inspire action – but couldn’t find a means to the end.

The idea to row oceans came to me in an instant, while I was on a long car drive. I would struggle to articulate where the idea came from. Those of a neuroscientific bent might suggest that, over the intervening months, my immersion in the subject and my persistent asking of the question about what I could do, had formed a network of neuronal connections that suddenly generated an insight, much as a mathematician or scientist struggling with a knotty problem might, after much perspiration, finally achieve inspiration. Or they may interpret it as emerging from the intuitive, creative, free-thinking, implicit and visual right hemisphere.

Those of a more metaphysical disposition might see it as a call to adventure. The literature is rather vague on what “call to adventure” actually means. Even Joseph Campbell, in Pathways to Bliss, wrote that “it is not always easy or possible to know by what it is that we are seized”, although the impact of receiving such a call is clear: “a person who is truly gripped by a calling, by a dedication or a belief, by a certain zeal, will sacrifice his (or her) security, personal relationships, prestige. He (or she) will give themselves entirely to their personal myth”.

But how we get from the not-knowing to the knowing remains mysterious.

The problem this presents, from the perspective of the person who has received the call, is that we know we must do the thing, while not yet fully understanding why. When life issues the call to adventure, it doesn’t send an instruction manual. So I have always struggled to answer the question of why I did what I did in terms of rowing across oceans. I can clearly see all the desires that were current in my life at that time, and how they contributed to the sense that this mission was the perfect embodiment of those desires, but I also know that this was not a left-brain exercise in putting those desires into a spreadsheet and producing an answer, or even of journaling my way to a solution. My subjective sense was that the vision arrived, perfectly formed, from somewhere outside of myself, be that the rather vague spiritual concept of “the Universe” or “Spirit”, or the Jungian collective subconscious, or somewhere/something else entirely.

Even at the time I set out across my first ocean, the Atlantic, I could still only metaphorically see a few oarstrokes ahead, and did not yet know how perfectly my adventures would fulfil all my objectives. As my adventures progressed, it seemed there was a transcendent genius at work, that could see a much bigger picture than I could, and had “known” from the outset just how brilliantly this would all work out.

Clearly, this is my interpretation. To someone who believes that what we see in the world is all there is, my narrative may seem fanciful, far-fetched, grandiose, or just plain crazy. Conversely, that person’s interpretation of what transpired in that moment of inspiration may strike me as prosaic, banal, lacklustre and humdrum.

We see the world not as it is, but as we are, to quote Anaïs Nin.

August 8, 2019

The Alphabet Versus The Goddess

I’m reading a fascinating book, titled as above, by Leonard Shlain. In all honesty, I’m only up to p72, but I wanted to share with you today as its message is very much on my mind.

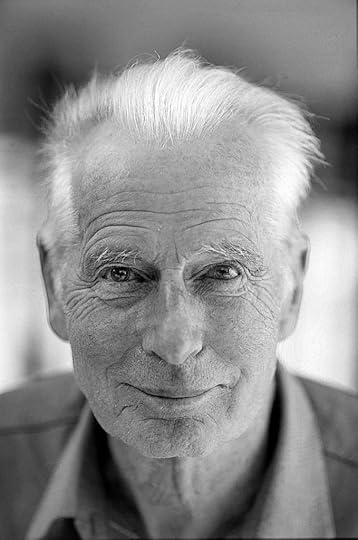

Leonard Shlain was quite the polymath, being a laparoscopic surgeon as well as an author, and inventor. He died in Mill Valley, California, in 2009 at the age of 71.

Leonard Shlain was quite the polymath, being a laparoscopic surgeon as well as an author, and inventor. He died in Mill Valley, California, in 2009 at the age of 71.

In The Alphabet Versus The Goddess, published in 1998, he seeks to prove his theory that the rise in written language precipitated a shift in the way we see the world, from right brain to left brain, from holistic to linear, from interconnected to reductionist, from feminine to masculine. The shift was not from one extreme to the other, but from a balanced position in the middle of the spectrum to a lop-sided emphasis on the left-brained masculine principle. This shift led to disrespect for the feminine principle, represented by the Goddess of the title, and increased individualism, patriarchy, and misogyny.

He disagrees with Riane Eisler (I blogged about her book, The Chalice and the Blade, last year) and others who pinned the blame on a group of Kurgan warriors for precipitating the paradigm shift from partnership to domination five thousand years ago. Rather, he claims it was the ascendancy of the written word.

This may seem puzzling. Literacy is surely a good thing, right? It has fast-tracked the ascendancy of humankind by enabling us to pass knowledge easily from one place and one generation to another. But bear with me/Leonard.

Most communication used to happen verbally and in person. When a person is speaking to us, we listen (well, some of us do, sometimes) but we also gather a lot of information by subconsciously noticing their tone of voice, facial expression, hand gestures, body language, and so on. Listening is a holistic experience.

Likewise, speaking is also a holistic experience. We gesture with both our hands, we exercise the muscles on both sides of our face, we use our tongue and our vocal chords and our lungs. Even while speech is generated in the left hemisphere (which is why a left-hemisphere stroke leaves people unable to speak), the right hemisphere is also active in sensing how our words are being received in real time interaction with our audience.

By contrast, reading and writing are much more predominantly left-brain activities. Rather than gesticulating with both hands, we pick up a pen in our dominant (usually the right) hand. We write linearly across the page. The communication is dependent entirely on the written word, without the depth and nuance of tone of voice, facial expression, or gestures (as you will appreciate if you have ever had a joke fall flat or a sensitive message be misunderstood when you sent it by text or email rather than in person).

At the point I’ve reached in the book, Shlain has established the correlation between the spread of the written word and the decline of the feminine principle, and hence the prestige of women. I’m not sure yet that he has established causation, but it’s certainly a fascinating idea. We know for sure that the technology we use changes us and our modes of thinking. And writing is as much a technology as your iPhone.

At the point I’ve reached in the book, Shlain has established the correlation between the spread of the written word and the decline of the feminine principle, and hence the prestige of women. I’m not sure yet that he has established causation, but it’s certainly a fascinating idea. We know for sure that the technology we use changes us and our modes of thinking. And writing is as much a technology as your iPhone.

Shlain is not the only great thinker to express concern about our shift towards a left-brained world – see also Iain McGilchrist’s excellent The Master and His Emissary.

The summary on the back of the The Alphabet Versus The Goddess assures me that: “Shlain ends his book with an optimistic appraisal that the proliferation of images in film, TV, graphics, and computers is once again reconfiguring the brain by encouraging right hemispheric modes of thought and bringing about the re-emergence of the feminine.” I’d like to believe that is true, although I have my doubts, given how many of those technological images are given over to violence, pornography, and other images detrimental to the feminine…. But I will read that part of the book with an open mind and hope to be convinced, because it’s certainly something I would like to believe.

What do you think? Certain political leaders aside, do you think there is a shift back towards the feminine principles of interconnection, holism, collaboration and nurturance? If so, what do you think is causing it? And do you see it as a good thing?

August 1, 2019

The Democratisation of Knowledge

I recently moved to Gloucestershire, and close to where I live there is a tall, thin tower standing on a hilltop, a monument to William Tyndale.

Poor old Billy Tyndale was strangled to death and his body then burned at the stake in 1536, for the “crime” of having translated the Bible into English. In fact, in England at that time, even the mere possession of scripture in English was subject to the death penalty.

It may seem bizarre to us now that the church would go to such extreme lengths to preserve its monopoly on access to scripture. The internet gives us the impression, rightly or wrongly, that almost all information is available to anybody with an internet connection. It’s easy to forget that five centuries ago most people would have had very little access to information; the printing press was still in its infancy, literacy rates were low, and certain powerful organisations were determined to maintain their privileged position by restricting access to the few rare and precious books.

Now, with a five-ounce iPhone in our pocket, we can access virtually all of human wisdom (and, arguably, an awful lot of human stupidity too). Tyndale’s brain would have boggled.

But do we make the most of this amazing privilege? Do we use this amazing facility in pursuit of truth and understanding? Hmm, maybe not so much. Rather than marvelling at the ongoing revelations from the worlds of physics, cosmology, zoology, biology, and the rest, too often we get sucked into the inconsequential (mentioning no Facebooks).

And, to some degree, there are still attempts to maintain monopolies over knowledge. I’m currently doing a DProf at the University of Middlesex, which entails a certain amount of academic literature. Some of the literature is marvellous in its lucidity and obvious willingness on the part of the authors to convey their learning to the reader. Most of it, again not so much. I sometime suspect a deliberate effort to obscure the inadequacies of the authors’ own understanding by veiling the information in so much academic jargon as to render their work virtually unreadable.

I don’t appreciate these power plays. If something matters enough to you, dear academic author, to spend years of your life researching it, please have the decency to explain it clearly in language that a layperson can understand. I sometimes finish slogging my way through a paper feeling that it may as well have been in the Hebrew or Greek that Tyndale translated, for all the sense I could make of it.

Tyndale paid the ultimate price for his belief that important knowledge should be available to anyone who wanted it. I propose we honour his sacrifice by seeking – and sharing – the truth for the benefit of all.

As a footnote, according to Wikipedia (now THERE is the powerful democratisation of knowledge!), these now well-worn phrases were first coined by Tyndale in his translation of the Bible:

my brother’s keeper

knock and it shall be opened unto you

a moment in time

fashion not yourselves to the world

seek and ye shall find

ask and it shall be given you

judge not that ye be not judged

the word of God which liveth and lasteth forever

let there be light

the powers that be

the salt of the earth

a law unto themselves

it came to pass

the signs of the times

filthy lucre

the spirit is willing, but the flesh is weak

live, move and have our being

July 25, 2019

Shambhala Warrior Mind Training

Last week I was at a festival in Somerset called Buddhafield. The name probably tells you all you need to know. Yes, there were buddhas and Tibetan singing bowls and prayer flags and lots of people in colourful clothes and some people in no clothes at all.

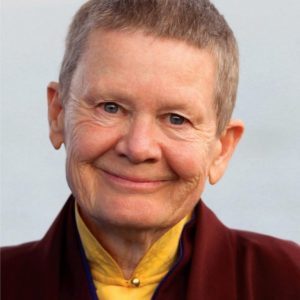

I went to a number of workshops, of which several were based on The Work That Reconnects (WTR), a methodology designed by the ecologist and Buddhist scholar and wonderfully wise Joanna Macy about 40 years ago. She describes it thus:

Joanna Macy

Joanna Macy“The central purpose of the Work that Reconnects is to help people uncover and experience their innate connections with each other and with the systemic, self-healing powers of the web of life, so that they may be enlivened and motivated to play their part in creating a sustainable civilization.”

So, in other words, it’s a holistic approach to ecological conservation, recognising the interconnection of everything on Earth by reconnecting with ourselves and with each other.

In practice, it seemed to require lots of staring into the eyes of strangers for several minutes at a time, which is a terribly un-British thing to do, but is actually incredibly powerful. I couldn’t help but think that if our global leaders were compelled to do these exercises, we would probably live in a dramatically different world.

There were also exercises that involved finishing such cheerful sentence stubs as: “When I think of the collapse of our civilisation, I feel sad because…”, or “When I think about the world we are leaving our children, I am concerned about…”.

I was sufficiently impressed with the work to want more, so I am going to a workshop on Deep Ecology, led by one of the session leaders from Buddhafield, in Bristol this Saturday.

When I came to look back over my notes from the festival, I found an unexplained reference to something called Shambhala Warrior Mind Training, which sounded cryptic and intriguing. Google led me to a short video of Joanna Macy explaining the Shambhala Prophecy, and also to the code of the Shambhala Warrior. The code really resonated with me, especially in my blissful post-festival state of peace and love, so I had it printed out and framed, and it now sits on my desk as a constant reminder of how to be in the world.

To some of you, it may seem rather abstract and hippie. To me, though (and to many of my compadres at Buddhafield, I’m guessing), it’s a recognition that our ecological crisis can’t be solved from the same level of consciousness that created it, that a fundamental shift in consciousness is required, to a worldview in which everything is connected, so that as we transform ourselves, we transform our reality.

“Hold in a single vision, in the same thought, the transformation of yourself and the transformation of the world.”

If you want to download the pretty pdf version that I created for my desk, click here. You’re welcome.

And here is a video of Joanna Macy talking about the prophecy of the Shambhala Warriors. I highly recommend it.

Shambhala Warrior Mind Training

Firmly establish your intention to live your life for the healing of the world.

Be conscious of it, honour it, nurture it every day.

Be fully present in our time. Find the courage to breathe in the suffering of the world.

Allow peace and healing to breathe out through you in return.

Do not meet power on its own terms.

See through to its real nature – mind- and heart-made. Lead your response from that level.

Simplify. Clear away the dead wood in your life.

Look for the heartwood and give it the first call on your time; the best of your energy.

Put down the leaden burden of saving the world alone.

Join with others of like mind. Align yourself with the forces of resolution.

Hold in a single vision, in the same thought, the transformation of yourself and the transformation of the world. Live your life around that edge, always keeping it in sight.

As a bird flies on two wings, balance outer activity with inner sustenance.

Following your heart, realise your gifts.

Cultivate them with diligence to offer knowledge and skill to the world.

Train in non-violence of body, speech and mind.

With great patience with yourself, learn to make beautiful each action, word and thought.

In the crucible of meditation, bring forth day by day into your own heart the treasury of compassion, wisdom and courage for which the world longs.

Sit with hatred until you feel the fear beneath it.

Sit with fear until you feel the compassion beneath that.

Do not set your heart on particular results.

Enjoy positive action for its own sake and rest confident that it will bear fruit.

When you see violence, greed and narrow-mindedness in the fullness of its power, walk straight into the heart of it, remaining open to the sky and in touch with the earth.

Staying open, staying grounded, remember that you are the inheritor of the strengths of thousands of generations of life.

Staying open, staying grounded, recall that the thankful prayers of future generations are silently with you.

Staying open, staying grounded, be confident in the magic and power that arise when people come together in a great cause.

Staying open, staying grounded, know that the deep forces of Nature will emerge to the aid of those who defend the Earth.

Staying open, staying grounded, have faith that the higher forces of wisdom and compassion will

manifest through our actions for the healing of the world.

When you see weapons of hate, disarm them with love.

When you see armies of greed, meet them in the spirit of sharing.

When you see fortresses of narrow-mindedness, breach them with truth.

When you find yourself enshrouded in dark clouds of dread, dispel them with fearlessness.

When forces of power seek to isolate us from each other, reach out with joy.

In it all and through it all, holding to your intention, let go into the music of life.

Dance!

July 16, 2019

Agroecology – Alleluia!

I’ll be honest – I was getting rather bored with writing this series on food production. I know it’s tremendously important – clearly, eating food is central to every person on the planet, so it’s one way we can all make a difference – but I was finding my own approach much too “left brain”, i.e. facts, figures and graphs, with some very sensible but not very emotionally compelling suggestions for how we can reduce our impact. And after half a century of environmental campaigning, if we know anything at all, it’s that facts and figures do not a difference make.

So I was about to can the whole series, and move onto something more interesting instead, when I remembered an email that was sent to me just after I started the series back in May, by Julie Abisgold.

Julie wrote:

“I have just read with interest, as usual, your email, Eating Ourselves Out Of House, Home, And Planet and look forward to reading your blogs on food production.

I’m wondering if you intend to say something about the efforts that many of us are making to ensure food production is more sustainable, both in developed and developing countries? There has been much progress over the last 10 years in awareness of the limitations of monocultures and the reliance on chemical pesticides and there are real positive changes happening both in farming practice and the availability of affordable alternatives for pest and disease control.

I appreciate that you are not an expert in this field (though you do an excellent job in presenting your information to a wide audience), but I would just like your readers to be aware that a lot of good things are happening in this space.”

And she included a couple of links which, I confess, I have only just clicked.

And Julie, I want to thank you from the bottom of my heart. You have given me hope.

What I was going to say, in signing off from the food production series, was that while we focus on individual problems, we simply seem to get more of the same. Change is, at best, incremental, rather than the dramatic turnarounds that we really need. What I believe we need is a fundamentally different story about the relationship between humans and the rest of nature (because we are part of nature, lest we forget).

We need to reconnect with the inescapable fact that we have one planet, on which everything is connected. There is neither an “away” for trash and toxins, nor is there any interplanetary supermarket from which we can miraculously import new topsoil or any of the other vital prerequisites that we are polluting and squandering as if there was, literally, no tomorrow.

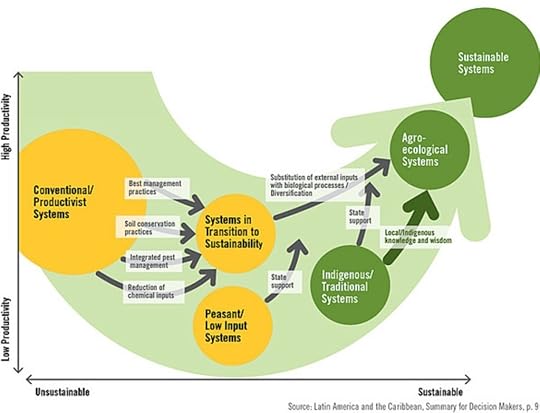

So I was enormously encouraged to follow Julie’s link to the National Farmers Union of Canada, and to see this page about Agroecology: “a holistic approach to food production that uses—and creates—social, cultural, economic and environmental knowledge to promote food sovereignty, social justice, economic sustainability, and healthy agricultural ecosystems.”

It features a quote from Ayla Fenton, former NFU Youth Vice-President, saying: “Agroecology is much more than a set of technologies; it is a political and social system, a way of life, a form of resistance against corporate control of the food system, and quite simply the only means of achieving food sovereignty.”

Now we’re talking!

I encourage you to read the whole page, and to follow the links to other agroecological resources. I particularly cheered when I read the last few “Pillars of Agroecology” (although in fact all the pillars are important and wonderful):

Direct, fair distribution chains, transparent relationships, and solidarity between producers and consumers are needed to displace corporate control of global markets and generate self-governance by communities.

Agroecology is political and requires us to transform the structures of power in society.

Youth and women are the principal social bases for the evolution of agroecology. Territorial and social dynamics must allow for leadership and control of land and resources by women and youth.

This is absolutely what we need. It is increasingly clear that corporate agribusiness is not serving the long term needs of people or planet. It is just another branch of capitalism, that sacrifices sustainability for short term profit.

I wholeheartedly applaud the work being done by NFU Canada to promote this sensible-yet-revolutionary approach. I would love to hear from anybody involved in Canadian farming – or anywhere else where agroecological principles are being adopted – about the real world impacts.

Julie’s other link took me to the Pesticide Action Network UK and Integrated Pest Management. Again, a radical outbreak of common sense. Hey, here’s a good idea: instead of blitzing the heck out of our arable land with pesticides, why don’t we adopt a “minimum effective response” approach using good husbandry, good field hygiene, and natural biological interventions. Saves money, saves the planet. What’s not to love about that?

Sure, it means the stewards of our land need to know more about the ecological systems that they’re working with, but isn’t that the point? When we know and appreciate the rhythms and behaviours of nature, we can work in harmony with them, rather than lazily carpet-bombing our natural world because we can’t be bothered to take a more subtle and nuanced approach.

Thanks again, Julie, for making my day/week/year. It’s inspiring to see these (literally) grassroots initiatives gaining national recognition and promotion. I hope and trust that they will go truly international and global.

July 11, 2019

The Ground Beneath Our Feet

I’m back at my desk, and back to writing about food production and its environmental consequences. I’ve already touched on soil degradation in a couple of previous blogs, but would like to dive in deeper today. We sometimes use the image of the ground beneath our feet to mean the one thing we can be totally sure of, can rely on with absolutely certainty, but it may not be so.

95% of our food comes from the soil, but about a third of the world’s soil has been degraded by modern farming techniques, deforestation, and global heating. The US Food and Agriculture Organisation warns that, unless new approaches are adopted, the global amount of arable and productive land per person in 2050 will be only a quarter of the level in 1960. According to the WWF, half the topsoil on the planet has been lost in the last 150 years.

Not good.

What are the main causes?

Erosion

Water, wind, and farming tillage can all contribute to soil erosion, which means that soil leaves where it is supposed to be – on the land – and ends up in drainage channels, streams, rivers, and lakes. It’s exacerbated by removal of plants and trees, either by deforestation or by the wildfires that are becoming more common as the planet warms. And it can be gradual, or it can be dramatic and lethal, as in the massive mudslides near Santa Barbara last year.

Erosion can be reduced by leaving plants, like alfalfa or winter cover crops, on farmland at the times of year when rain is most likely. The plants help lessen the impact of the rain on the soil, and also provide a conduit for the raindrops to seep into the soil rather than washing off the surface. Contour farming and strip-cropping also help.

LOTS more about soil erosion on this website.

Loss of Quality

Soil depletion due to some farming practices leaves the soil less fertile, mostly by reducing the microbial activity of the soil.

Deforestation

Deforestation is a triple environmental whammy. Trees provide generous amounts of leaf litter and fallen branches to create humus, which is important for the soil’s aeration, water holding capacity, and biological activity like worms. Logging worsens erosion. And of course the loss of those trees reduces the earth’s capacity to convert CO2 back into oxygen through photosynthesis.

Excessive Use of Fertilizers

Excessive use and misuse of pesticides and chemical fertilizers kill the multitude of tiny organisms, like bacteria and other micro-organisms, that bind soil together. The fertilizer’s chemicals also denature essential soil minerals, leading to nutrient losses from the soil.

Industrial and Mining Activities

Mining removes plant cover, and releases a toxic mix of chemicals like mercury into the soil, poisoning it. Industry releases toxic effluents into the air, land, rivers and ground water that pollute the soil.

Urbanisation

As our cities grow, we pave over more and more green areas with concrete and tarmac. As well as replacing greenness with greyness, all those non-absorbent surfaces increase runoff, which in turn increase erosion. And it’s not nice rainwater – by the time it has washed down our streets, it is polluted with oil, fuel, tyre rubber, and other junk.

Plastic

I’ve heard that in China, the plastic that they use to cover fields is not removed when no longer needed, but ploughed into the soil, to the extent that many fields now appear white rather than brown when bare of crops. I haven’t been able to verify this exactly, although this article describes a similar problem. Yuck.

Seawater Inundation

As icecaps melt and sea levels rise, more coastal areas are being flooded, which contaminates the land with salt. You might remember from your history lessons that salting the earth is what victors used to do to render land uninhabitable because the salt would prevent crops from growing.

Well, there’s more, but that’s enough to be going on with, before we get too overwhelmed.

How do we turn this around?

First, what are we aiming for? Here’s a soil enthusiast talking about what soil should look like.

And second, what can we as individuals do to promote this lovely, rich, wormy soil?

Do our bit to curb industrial farming.

Eat less meat and dairy, and more fruit and veg, to reduce the need for tilling, multiple harvests and agrochemicals. Eating lower on the food chain is a much more efficient use of our agricultural land.

Bring back the trees.

Plant trees, and vote for policies that promote sustainable forest management and reforestation schemes.

Stop or limit ploughing.

In your own garden, adopt a no-dig policy. Support farmers who adopt a zero-tillage strategy, and make sure no soil is left exposed by sowing cover crops directly after harvest.

Replace goodness.

Compost, pony poo, seaweed, whatever you can find that will enrich your soil.

Leave it be.

When land is left to recover, nature does a marvellous restoration job. Hydroponics, vertical farming, and switching to mostly or entirely vegan diets all reduce our currently insatiable demand for land for food production.

If you doubt your power to make a difference, don’t! We’ve mostly ended up with these challenges through the billions of micro-decisions we all make every day about what to eat, and who to buy it from. So we need to start making better micro-decisions, and spreading the word. We all make a difference, all the time – make it a good one!

June 27, 2019

The Hero Path

Today’s blog post is courtesy of Joseph Campbell, author of The Hero with a Thousand Faces and many other books, good friend of George Lucas, and inspiration behind Star Wars. I heard this quote during an episode of the excellent On Being podcast, hosted by Krista Tippett, in an interview with Father Richard Rohr. This really resonated with me, and I thought it might with you too.

[I’m on the road at the moment, hence shorter-than-usual blog post. Normal service will be resumed in July.]

We have not even to risk the adventure alone

for the heroes of all time have gone before us.

The labyrinth is thoroughly known …

we have only to follow the thread of the hero path.

And where we had thought to find an abomination

we shall find a God.

And where we had thought to slay another

we shall slay ourselves.

Where we had thought to travel outwards

we shall come to the center of our own existence.

And where we had thought to be alone

we shall be with all the world.