Roz Savage's Blog, page 20

April 11, 2019

Society and the Veil of Ignorance

[Including a personal update at the end, under Other Stuff…]

I was intrigued by this recent article by one of my regular reads on medium.com, Umair Haque, on this occasion writing about when luxuries become necessities and necessities become luxuries, which he claims has happened in the US. To summarise, he says that capitalism has laid claim to things that used to be basic essentials (and in many countries still are), like social interaction, medicine, nutritious food, public transport, education … even life itself. At the same time, he says, Americans are bombarded with messages that normalise McMansions, prestige cars, designer clothes, and the kind of physical perfection that for the vast majority of people requires cosmetic surgery, until they start to regard these as necessities.

“Capitalism creates intense, perpetual, ever-mounting status competition this way — by making luxuries false necessities. It preys on basic human needs, and then twists them upside down, teaching people luxuries are necessities, but necessities are luxuries.”

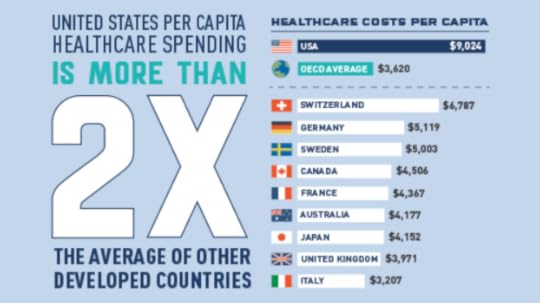

Umair is big on passion, but low on citations, so I decided to do some cross-checking. For example, what is the true story about the price of healthcare?

“America’s getting plenty angry about the rising cost of insulin—and no wonder. Between 2002 and 2013, the average price for this life-saving, injectable drug used by nearly 10 million Americans with diabetes has tripled, according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA).” (OnTrackDiabetes)

“America’s getting plenty angry about the rising cost of insulin—and no wonder. Between 2002 and 2013, the average price for this life-saving, injectable drug used by nearly 10 million Americans with diabetes has tripled, according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA).” (OnTrackDiabetes)

“Diabetic ketoacidosis is a terrible way to die. It’s what happens when you don’t have enough insulin. Your blood sugar gets so high that your blood becomes highly acidic, your cells dehydrate, and your body stops functioning. Diabetic ketoacidosis is how Nicole Smith-Holt lost her son. Three days before his payday. Because he couldn’t afford his insulin.” (NPR)

“According to the most recent data available from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), “the average American spent $9,596 on healthcare” in 2012, which was “up significantly from $7,700 in 2007.” It was also more than twice the per capita average of other developed nations, but still, in 2015, experts predicted continued sharp increases: “Health care spending per person is expected to surpass $10,000 in 2016 and then march steadily higher to $14,944 in 2023.” Indeed, average annual costs per person hit $10,345 in 2016. In 1960, the average cost per person was only $146 — and, adjusting for inflation, that means costs are nine times higher now than they were then.” (CNBC)

“A new study from academic researchers found that 66.5 percent of all bankruptcies were tied to medical issues —either because of high costs for care or time out of work. An estimated 530,000 families turn to bankruptcy each year because of medical issues and bills, the research found.” (CNBC)

What is it that we should be aiming for?

The last time we as a species took the opportunity to step back and declare our highest aspiration was just after we emerged from the horrors of World War II. Having discovered our own lethal capability when nuclear bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we took a moment to reflect and ask ourselves: Who are we? What do we stand for? What do we want our future civilisation to look like?

So there was a flurry of activity including Bretton Woods (1944), the United Nations (1945), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), and the formation of the World Health Organisation (1946). The WHO Constitution defines health as: “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. Article 25 of the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.”

So there was a flurry of activity including Bretton Woods (1944), the United Nations (1945), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), and the formation of the World Health Organisation (1946). The WHO Constitution defines health as: “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. Article 25 of the United Nations’ 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services.”

As we’re increasingly seeing with the Paris agreement on climate change, supranational organisations are great at grand declarations of intent, not so good at ensuring that they are enforced, but my point is that this is what we believed to be important in our moment of highest aspiration, when we were making our post-war, new era resolutions. It seemed self-evident that universal access to the things that support health, and the medicines that restore health, would be a Good Thing, not just for the poor and sick, but for everybody.

Some countries took the resolution and ran with it, like the social democracies of Scandinavia. You will notice that there is a remarkable overlap between the countries that adopted social democracy, and the happiest countries in the world.

We’re all in this together

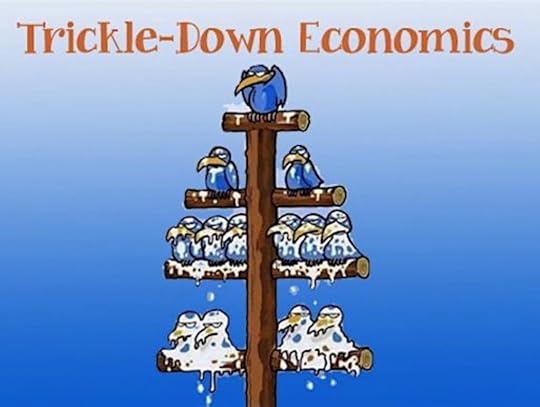

The core message is that we’re all in this together. A society is happier and healthier when it takes care of all its citizens. Collaboration works better than competition.

The core message is that we’re all in this together. A society is happier and healthier when it takes care of all its citizens. Collaboration works better than competition.

But aren’t humans comparative beings? Don’t we like to feel like we’re better off than the next guy? Don’t we prefer to have the best house in a crappy street than an objectively better, but comparatively crappy house in a very grand street?

Yes, but societies as a whole do better when inequality is reduced, when the wealth of a nation is distributed so as to ensure that everybody has enough of what they need – education, food, healthcare.

We have been told (notably by Margaret Thatcher – although she may have been misunderstood) that there is no such thing as society, that we are intrinsically selfish and self-serving, and that perfect competition is the best way to organise ourselves.

Neoclassical economists may tell us this story. But psychologists tell us a different story. They point to the emotional and physical benefits of altruism, with positive impacts on stress levels, mood, health, and even longevity.

Philosophers such as Alain de Botton also encourage greater empathy, and a kinder, gentler, definition of success:

“…in the Middle Ages, in England, when you met a very poor person, that person would be described as an “unfortunate” — literally, somebody who had not been blessed by fortune, an unfortunate. Nowadays, particularly in the United States, if you meet someone at the bottom of society, they may unkindly be described as a “loser… That’s exhilarating if you’re doing well, and very crushing if you’re not… I think it’s insane to believe that we will ever make a society that is genuinely meritocratic; it’s an impossible dream… The idea that we will make a society where literally everybody is graded, the good at the top, bad at the bottom, exactly done as it should be, is impossible. There are simply too many random factors: accidents, accidents of birth, accidents of things dropping on people’s heads, illnesses, etc. We will never get to grade them, never get to grade people as they should.”

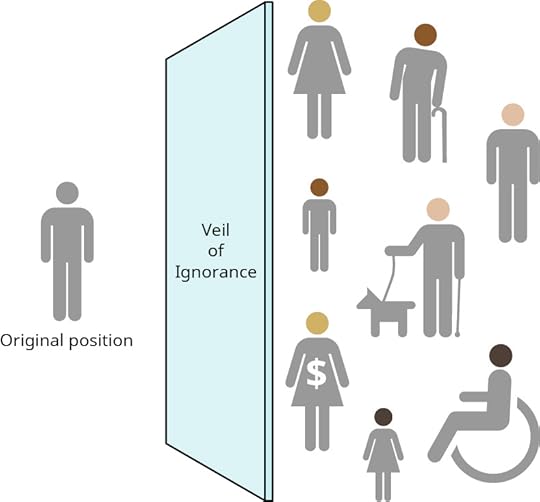

The Veil of Ignorance

The Veil of Ignorance

I’m a fan of the veil of ignorance idea, which suggests that those in a position to make laws or any major decisions that affect a significant number of people in a society or organisation, should imagine that they do not know what their role would be in that society or organisation.

So if, for example, you’re deciding on a healthcare policy, you imagine that you don’t know if you are a billionaire or a homeless person, so you create a policy that works for those extremes of the spectrum, and everybody in between. Ditto for your tax policy, education, justice, gender, employment rights, food standards, and so on. You imagine that you don’t know whether you will be wealthy or poor, male or female, black or white, healthy or sick, young or old. You avoid creating scenarios that you wouldn’t want to be in yourself.

“The natural distribution is neither just nor unjust; nor is it unjust that persons are born into society at some particular position. These are simply natural facts. What is just and unjust is the way that institutions deal with these facts.”

― John Rawls, A Theory of Justice

Sound like a good idea? I think so.

Sound like what most countries have at the moment? I think not.

Other Stuff:

With all these big questions going on, I don’t write much about myself these days, but some people have been curious to know what I’m up to. So here’s a quick update. My primary paid work is as a keynote speaker. So far this year I’ve spoken in London, Kuwait, and Portugal (twice), for clients such as Dell computers, Experian, Patsnap, and the Royal London Group. I also usually do a lot in the US – I made six trips to North America last year, speaking for corporate clients like Autodesk and Clorox, as well as the National Aquarium in Baltimore and the Ocean Institute in California.

I’ve also just started a doctorate at the University of Middlesex (DProf by Public Works) and with the Sisters, my new women’s network, we’re currently piloting a new concept we’re calling Illuminations: a series of deep dives into issues that matter, through individual study and group discussion in real life gatherings, with the intention of sparking projects to create a better future, which we then crowdsource – not just with financial resources, but also with networking and mentoring. I’m working with a team based in the US and Indonesia on a new tech platform that will really support our vision for a vibrant and collaborative network of women around the world.

Some of you ask about my mother, who was such a key member of my team during my ocean rowing years. She’s doing well, still volunteering with a local organisation in Yorkshire and keeping busy, and we celebrated her 80th birthday in January. My sister continues to pursue epic hikes – she and her boyfriend completed the Continental Divide Trail last year, and having done the Pacific Crest Trail in 2012, they are now hatching plans to do the Appalachian Trail to complete the Triple Crown.

And finally, yesterday we went live with a new addition to my personal website – you can now download printable Roz quotes, in English, Hindi, Spanish, French, German, Italian, Chinese, Japanese or Russian! Thanks to Steve Perry for all his good work on this.

April 4, 2019

Economics and Ecosystems

Some great snippets from Money and Sustainability: The Missing Link, a report by Bernard Lietaer et al, selected for your delectation…

A fish will never create fire while immersed in water. We will never create sustainability while immersed in the present financial system. There is no tax, or interest rate, or disclosure requirement that can overcome the many ways the current money system blocks sustainability.

…

Viable complementary currency systems are not alone sufficient to halt our headlong drive towards disaster. But we have no chance of avoiding collapse without them.

…

This Report shows that the current money system is both a crucial part of the overall sustainability ‘problem’ and a vital part of any solution. It makes clear that awareness of this ‘Missing Link’ is an absolute imperative for economists, environmentalists and anyone else trying to address sustainability at a national, regional or global level. Aiming for sustainability without restructuring our money system is a naïve approach, doomed to failure.

…

The money system is bad for the money system itself. Unless we fundamentally restructure it, we cannot achieve monetary stability. Indeed, this Report also demonstrates that monetary stability itself is possible if, and only if, we apply systemic biomimicry – that is to say, if we complement the prevailing monetary monopoly with what we call a ‘monetary ecosystem’.

…

Environmentalists often try to address the ecological crisis by thinking up new monetary incentives, creating ‘green’ taxes or encouraging banks to finance sustainable investment. Economists, in turn, tend to believe the financial crisis can be ‘fixed’ and kept from recurring with better regulation and a strict, prolonged reduction in public spending. But, whether they are advocating greener taxes, leaner government budgets, greener euros or dollars or pounds, could both camps be barking up the wrong tree?

…

In order to face the challenges of the 21st century, we need to rethink and overhaul our entire monetary system.

…

Rather than defining environmental and social issues as ‘externalities’, our approach sees economic activities as a subset of the social realm, which, in turn, is a subset of the biosphere. This view provides the basis for the emergence of a new set of pragmatic tools, flexible enough to address many of our economic, social and environmental challenges.

I highly recommend the report in its entirety.

Other Stuff: Polly Higgins

In a recent blog post, I mentioned the stellar work being done by Polly Higgins and her campaign against ecocide (to criminalise the deliberate destruction of the natural environment). So it was with great shock that I learned that Polly has recently been diagnosed with terminal cancer, and given just 6 weeks to live. Her global community of friends is giving her all the love and support that we can. Even if you don’t know Polly, please show your support for her and her mission by signing up to be an Earth Protector, and invite your friends and family to do likewise. The invitation to sign up is on Polly’s Facebook page, and the Earth Protector signup is on her Mission Lifeforce page. Her team say:

“sign up as an Earth Protector at IAmAnEarthProtector.org – and get 20 of your mates to sign up too… Polly says she would love to *live* to see #OneMillionEarthProtectors … wouldn’t that be incredible?!”

March 28, 2019

Unfreedom

These are interesting times for democracy. It was 1947 when Winston Churchill said:

“‘Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”

… and that was before social media came along and stuck its oar in (so to speak).

Over the last couple of weeks, a number of ideas from various media have passed through my sphere of attention, and they seem to connect. Please indulge me, as we take a rollercoaster ride through the 2016 US election, Brexit, Russia, wildly unethical social psychology experiments, and the coming out of Yuval Noah Harari, to arrive at a tentative conclusion about free will, or our lack thereof.

The Road to Unfreedom: Russia, Europe, America, a book by Timothy Snyder

Timothy Snyder is a professor of history at Yale, so I assume he knows what he is talking about – even if Mueller doesn’t agree with him. He says that, “Russia works within the West to destroy the West; by supporting the far right in Europe, invading Ukraine in 2014, and waging a cyberwar during the 2016 presidential campaign and the EU referendum. Nowhere is this more obvious than in the creation of Donald Trump, an American failure deployed as a Russian weapon.” He claims that Trump’s failing businesses were propped up by Russian money, which served the useful triple purpose of laundering the money, putting Trump firmly in the pockets of the Russians, and enabling him to apply to himself the label of “VERY successful businessman” for campaigning purposes.

Snippets from the book that support these claims:

“Though bots are less numerous than humans on Twitter, they are more efficient than humans in sending messages. In the weeks before the election, bots accounted for about 20% of the American conversation about politics. An important scholarly study published the day before the polls opened warned that bots could “endanger the integrity of the presidential election.””

“In several hundred cases (at least), the very same bots that worked against the European Union attacked Hillary Clinton. Most of the foreign bot traffic was negative publicity about her. When she fell ill on September 11, 2016, Russian bots massively amplified the scale of the event, creating a trend on Twitter under the hashtag #HillaryDown. Russian trolls and bots also moved to support Trump directly at crucial points. Russian trolls and bots praised Donald Trump and the Republican National Convention over Twitter. When Trump had to debate Clinton, which was a difficult moment for him, Russian trolls and bots filled the ether with claims that he had won or that the debate was somehow rigged against him. In crucial swing states that Trump won, bot activity intensified in the days before the election. On Election Day itself, bots were firing with the hashtag #WarAgainstDemocrats.”

“In several hundred cases (at least), the very same bots that worked against the European Union attacked Hillary Clinton. Most of the foreign bot traffic was negative publicity about her. When she fell ill on September 11, 2016, Russian bots massively amplified the scale of the event, creating a trend on Twitter under the hashtag #HillaryDown. Russian trolls and bots also moved to support Trump directly at crucial points. Russian trolls and bots praised Donald Trump and the Republican National Convention over Twitter. When Trump had to debate Clinton, which was a difficult moment for him, Russian trolls and bots filled the ether with claims that he had won or that the debate was somehow rigged against him. In crucial swing states that Trump won, bot activity intensified in the days before the election. On Election Day itself, bots were firing with the hashtag #WarAgainstDemocrats.”

“Americans were not exposed to Russian propaganda randomly, but in accordance with their own susceptibilities, as revealed by their practices on the internet. People trust what sounds right, and trust permits manipulation. In one variation, people are led towards ever more intense outrage about what they already fear or hate.”

The New Yorker: The Chaotic Triumph of Arron Banks, the “Bad Boy of Brexit”

“The Conservative M.P. Damian Collins has demanded a broader inquiry into Russian interference in British affairs. In an interview at his office in the Houses of Parliament, he told me that he had serious concerns about the source of [Arron] Banks’s funds. “The reason the questions persist is that he seems to own a number of businesses that don’t make any money,” Collins said. “There’s never really been a clear explanation from him about the funding of these campaigns.”…

“The Conservative M.P. Damian Collins has demanded a broader inquiry into Russian interference in British affairs. In an interview at his office in the Houses of Parliament, he told me that he had serious concerns about the source of [Arron] Banks’s funds. “The reason the questions persist is that he seems to own a number of businesses that don’t make any money,” Collins said. “There’s never really been a clear explanation from him about the funding of these campaigns.”…

…Late last year, e-mails leaked to the Observer revealed that Leave.EU had misrepresented to British investigators the extent of its ties to Cambridge Analytica, the now disgraced and insolvent British data firm funded by the [conservative] American political donor Robert Mercer to microtarget voters. In “The Bad Boys of Brexit,” Banks flatly states that Leave.EU had “hired Cambridge Analytica.””

Please remind yourself about Cambridge Analytica, euphemistically described by Wikipedia as an “English political consulting firm which combined data mining, data brokerage, and data analysis with strategic communication during the electoral processes”. This means they bought illegally-acquired user data, and how they used it is still the subject of ongoing criminal investigations in the US and UK. Steve Bannon is its former vice-president.

Experimenter: a movie about Stanley Milgram

A quirky film, this highlights the work of the famed (even notorious) social psychologist who conducted a series of experiments in the 1960s during his professorship at Yale. You may well have heard of them. In his “Behavioural Study of Obedience”, he had subjects come into his lab, where they were instructed to administer a memory test to the “learner”, who was in fact an actor in cahoots with Milgram. The punishment for a wrong answer was an electric shock, and the more wrong answers the learner/actor gave, the stronger the shock became. Although the subject and the learner/actor were in separate rooms so they couldn’t see each other, the learner/actor would emit suitably heart-rending shrieks of pain as the shocks were administered. If the subject questioned the experiment supervisor, a man in a white lab coat (mark of authority) about whether he should continue, he was instructed to do so, even as the shocks reached supposedly potentially fatal levels.

Two thirds of the subjects went all the way to the strongest possible shock. Many of them turned in concern to the supervisor, but when he said, “Please continue”, they meekly returned to the question-answer-shock routine.

Two thirds of the subjects went all the way to the strongest possible shock. Many of them turned in concern to the supervisor, but when he said, “Please continue”, they meekly returned to the question-answer-shock routine.

To put this into context, Milgram was inspired to conduct this experiment by the Holocaust. He wondered how so many individuals, who before the war had been ordinary people, not homicidal maniacs, commit such atrocities in the name of Hitler. His chilling conclusion was: “the essence of obedience consists in the fact that a person comes to view himself as the instrument for carrying out another person’s wishes, and he therefore no longer sees himself as responsible for his actions. Once this critical shift of viewpoint has occurred in the person, all of the essential features of obedience follow.”

Solomon Asch’s conformity experiments

This work was also referenced in Experimenter. The experiment consisted of a single subject being introduced into a group between 5 and 7 of Asch’s stooges, who the subject naively understood to be participants just like himself. The group would be shown two pieces of card. On the first card was a single line. On the second card were three lines of varying lengths. Each person had to say which of the lines on the second card was the same length as the line on the first card. The only true subject in the group would answer last or second-to-last.

For the first few runs of the test, the stooges would give the obvious, correct answer. After that they gave a wrong answer in around 12 out of 18 of the subsequent runs. Out of the 123 male subjects who took the test in innocence of the deception, around 1 in 20 caved in completely and agreed with the wrong majority. Around 1 in 4 withstood the peer pressure. The remainder conformed in some runs but not others – in other words, they doubted the evidence of their own eyes, and conformed to the group in giving the wrong answer.

The Big Short – movie

This is another quirky film in which, like The Experimenter, random actors directly address the camera to explain what is going on, so we get Margot Robbie sitting in a bubble bath sipping champagne while she explains “collateralized debt obligations”.

This is another quirky film in which, like The Experimenter, random actors directly address the camera to explain what is going on, so we get Margot Robbie sitting in a bubble bath sipping champagne while she explains “collateralized debt obligations”.

The 2008 financial crash was triggered by the collapse of the sub-prime mortgage bubble, a situation largely created by greed, groupthink (as in Asch), and the invisibility of the consequences from the viewpoint of the perpetrators (as in Milgram). As Brad Pitt’s character points out, when unemployment goes up 1%, 40,000 people will die. The collapse would destroy jobs, homes, and families, but while there was a buck or a billion to be made, bankers were willing to ignore the catastrophic impacts of their activities.

And yet, despite the massive and deliberate fraud going on at the highest levels, to quote the Mark Baum character: “”I have a feeling, in a few years people are going to be doing what they always do when the economy tanks. They will be blaming immigrants and poor people.”

Interview with Yuval Noah Harari (author of Sapiens, Homo Deus, etc) and Tristan Harris, Director of the Centre for Humane Technology

(Notes extracted and paraphrased from the interview)

TH: As a magician and expert on persuasion, I learned there are hacking techniques that work on everyone, regardless of age, nationality, or IQ.

YNH: Democracy is built on the idea that we are rational decision-makers, but now we know our free will is not so free. Corporations and governments now have the technology to hack us. They have been able to progress from understanding our choices, to predicting them, to manipulating them.

YNH: Democracy is built on the idea that we are rational decision-makers, but now we know our free will is not so free. Corporations and governments now have the technology to hack us. They have been able to progress from understanding our choices, to predicting them, to manipulating them.

TH: Think of your mind like a chess game. When you go to YouTube (or any other social media site) you expose your mind to the Google supercomputer, which has, in effect, run chess simulations billions of times. Whatever you do, it is one step ahead of you, and it will most likely win this game. And the algorithm doesn’t care what you want, or what is good for you – its objective is to keep you on the screen for as long as possible, and it’s really good at it.

70% of videos watched on YouTube are not what you first searched for, they’re from the “Up Next” strip on the right. 1.9 billion people spend an average of 1 hour a day on YouTube. This gives YouTube massive power to sway public opinion.

The AI algorithm has no conscience: it just maps the most common patterns of behaviour. If it knows that watching a video on dieting is often followed by watching a video on anorexia, it will recommend it, without caring that it could be leading a vulnerable teenager towards an eating disorder.

And picture this: a government setting up hundreds or thousands of “bots” to “watch” a very popular video, then “watching” a video extolling the virtues of Vladimir Putin. This pattern will become engrained in the algorithm, pushing the Putin propaganda – and hence Putin – up the rankings.

Even more creepy, your personal technology could be spying on you. The camera could be scanning your face to detect when you show signs of emotional arousal, such as dilated pupils or a raised heartbeat (yes, it really can do that). So even as you’re watching a video, it can “know” how you’re responding, probably better than you know yourself. YNH illustrated this point thus: he didn’t acknowledge until he was 21 that he’s gay. A camera scanning his face could have told him sooner – for example, by observing whether he was paying more attention to David Hasselhoff or to Pamela Anderson. And when technology knows you better than you know yourself, you’re vulnerable.

Conclusion

To put all this into a nutshell, I will re-quote from The Road to Unfreedom:

“Americans were not exposed to Russian propaganda randomly, but in accordance with their own susceptibilities, as revealed by their practices on the internet. People trust what sounds right, and trust permits manipulation.”

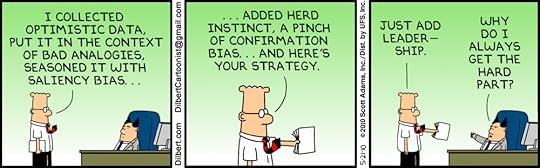

This is at the heart of what ails us at the moment, in so many ways. Confirmation bias research tells us unequivocally that we filter information to reinforce what we already “know”, while ignoring contradictory evidence. The brain favours coherence over accuracy, so a nice, neat, coherent story will prevail over truth, which is often messier.

And, by definition, we can’t see our blind spots. Put another way, we can’t see the water we’re swimming in, and while we’re in the water we are susceptible to peer pressure, propaganda, manipulation, obedience to authority, even to advertising. We are not free.

And, by definition, we can’t see our blind spots. Put another way, we can’t see the water we’re swimming in, and while we’re in the water we are susceptible to peer pressure, propaganda, manipulation, obedience to authority, even to advertising. We are not free.

Asked how we can protect ourselves against hacking, Yuval Noah Harari strongly suggests, “know thyself”. Only when we know our own prejudices, susceptibilities, and preferences, can we notice when all our inputs seem to be agreeing with us just a bit too much.

Heck – this whole blog post is a prime example! I’ve read and watched various things, and have picked out the elements that reflect my pre-existing concerns, and have now offered them to you as something approaching “truth”.

I trust that the difference is that I am sincerely not trying to manipulate you, I am trying to warn you. We are all being hacked, it is just a question of how much. At least, once we’re aware of it, we can take precautions against it – and I don’t just mean by putting a piece of sticky tape over your laptop camera.

We need to be alert, to maintain a stance of critical thinking, to check in on the independence of our views, to notice when others disagree with us and get curious about what they may know that we don’t. We can’t rely on our digital newsfeeds to give us an objective view of the world, and this really, really matters.

Exactly at the time when we need our leaders to be making smart decisions, our ability to choose the right leaders is being undermined. We need to be vigilant, as never before. Truth and freedom – even our perception of reality – are under threat. Ultimately, we may need a new kind of democracy, but for now, those of us who care about the future have a duty to stay alert, and to be aware that the waters in which we swim are increasingly murky.

March 21, 2019

Of Brexit and Biophysics

Many of my friends are Americans, and I spend a fair bit of time on the left hand side of the pond. Very often, as the sole Brit in a gathering, I am asked what I think of Brexit.

This normally elicits an involuntary eye roll and a sigh – not because I don’t want to talk about it, but because I don’t really know what to say, or at least not in polite company. It’s a mess.

Mostly, I have put Brexit into the bucket of “things that affect me but I can do nothing about”. If I get too caught up in the daily drama of negotiations, votes, amendments, extensions, backstops, and rebellions, it doesn’t make me feel good, and to be honest, I long ago lost track of the detail of what’s going on.

“Blame him”

“Blame him”I still harbour a lingering resentment towards David Cameron, who held the referendum in a bid to lay to rest forever the European question and, not to put too fine a point on it, completely ballsed it up by: a) misreading his audience/electorate, b) running a lacklustre Remain campaign, c) not foreseeing that Europe would absolutely punish the UK as the first country to break ranks, and d) not requiring at least 50% of the total electorate to vote for Brexit, not just 50% of those who turned out on the day. I’m also not delighted with Boris Johnson (with apologies to his father, Stanley, who is a dear friend of mine, and is in no way to be blamed for the actions of his son), who misrepresented the financial benefits of

Brexit in a bid, some might say, to further his own political career.

(If you’re a total policy nerd and want the nitty-gritty from a more reliable source than me, I commend the insightful (and even occasionally humorous) articles written by my old University College, Oxford acquaintance, Anand Menon, now Professor of European Politics and Foreign Affairs at King’s College London, who writes for The Guardian, and has also co-authored a book entitled Brexit and British Politics.)

I suspect that, if we were to have a second referendum, it would probably go the other way. Now that we’re starting to see the consequences of Brexit, as companies move their financial and manufacturing operations out of the UK, as we see the impact on funding for universities and research, as the property market slows and dips, the UK becomes the world’s biggest buyer of refrigerators as the NHS stockpiles medicines, and all the rest of it, we are beginning to understand what a post-Brexit UK will look like, and it’s not a pretty picture. Also, given that older people were more likely to vote to leave while youngsters favoured remain, the demographic shift that has taken place in the nearly 3 years since the first referendum, as old people die and young people achieve voting age, would probably tip the balance in favour of remaining in the EU. But it’s not likely to happen, and even if it did, it could create as many problems as it solves.

Guess now we get to see what a post-growth world looks like…

Guess now we get to see what a post-growth world looks like…The reasons to dislike Brexit are many – even beyond the saturation media coverage (yawn), the threat of imports of American-produced food that doesn’t meet European standards, the damage to British job prospects, and the general shame of taking part in an entirely non-fact-based referendum result (the two most Googled terms in the UK were “what does it mean to leave the EU?” and “what is the EU?” – the day AFTER the referendum) – the thing that annoys me most is that Brexit is taking up practically all of our national bandwidth at precisely the time that we should be paying attention to rather bigger issues, like the unravelling Arctic, collapsing insect populations, the sixth mass extinction, and imminent climate collapse. At the same time, we’re potentially losing the 80% of our environmental protections that come from EU law (detailed breakdown here).

Theresa May, that diligent schoolgirl tasked with the worst homework assignment of all time, but determined to see it through no matter what, obviously doesn’t have time to think about long term environmental concerns while she ping-pongs between Brussels and the House of Commons on her mission impossible. Sure, the clock is ticking towards March 29th, when we are due to leave the EU, with no deal yet in place. But in the overall scheme of things, that clock is a small and insignificant clock compared with the planetary clock that is ticking away our last chances to change course for sustainability. These are crucial years for humanity, and at least as the UK is concerned, we’re in danger of focusing on the “urgent but not important” at the expense of the “increasingly urgent and existentially important”.

Politics may matter, but biophysics are irrefutable.

March 14, 2019

Possibly The Only Time I Will Ever Write About The Kardashians

I don’t know why, but I find it rather depressing that Kylie Jenner has just become the world’s youngest ever billionaire, at the age of 21, based on income from her cosmetics empire. I’ve tried to figure out why I feel this way. Is it:

Kylie Jenner (in case you didn’t know)

Kylie Jenner (in case you didn’t know)Envy? Am I just bitter and twisted because she is less than half my age and worth… well, shall we just say a large multiple of my personal wealth? When I was a little girl I used to daydream that my parents were actually adopted, and my true parents were a king and queen who would one day show up to claim their princess, after which I would live in a castle and wear beautiful dresses. Am I jealous that Kylie got born into the 21st century equivalent of a royal family – a reality TV family?

Is it because I’m proud to be a woman, yet obviously it is mostly women who have put Kylie where she is now by buying her over-priced and over-packaged cosmetics? Am I ashamed by our collective gullibility?

Is it because we (or at least, some of us) still idolise youth and wealth over more durable and admirable personal attributes, like courage, character, and contribution? Why should we care that a young, over-privileged socialite has a ten-figure fortune while the world goes to hell in a hand-basket?

Or am I just being generally grouchy, far beyond the relatively insignificant Kylies of the world, because humanity is facing extinction rather sooner than I had expected? It’s enough to put anybody in a bad mood.

I don’t think it’s so much princess-envy or woman-shame. I’d like to think, rightly or wrongly, that I’m bigger than that. I think it’s more to do with my general despair about how we still measure success by the size of someone’s bank balance rather than the size of their heart.

Yes, many rich people are major philanthropists and give away millions to good causes (even if their personal fortune is so vast that it still grows, no matter how fast they give it away). Heck, during my ocean rowing years I was on the receiving end of some incredible generosity, and I’m certainly grateful and appreciative. To be absolutely clear, I am not critical of the individuals whose hard work and/or good fortune has brought them great wealth. It’s the system that I’m questioning.

While we continue to lionise the wealthy and correlate financial riches with happiness (despite extensive research disproving the connection beyond a certain level), we perpetuate the myth of infinite growth on a finite planet. If we’re all striving to live the m/b/zillionaire lifestyle, with planes and yachts and mansions, we’re going to continue to head in completely the wrong direction sustainability-wise (see this no-punches-pulled diatribe by Marc Doll).

While we continue to lionise the wealthy and correlate financial riches with happiness (despite extensive research disproving the connection beyond a certain level), we perpetuate the myth of infinite growth on a finite planet. If we’re all striving to live the m/b/zillionaire lifestyle, with planes and yachts and mansions, we’re going to continue to head in completely the wrong direction sustainability-wise (see this no-punches-pulled diatribe by Marc Doll).

We need, as Alex Evans argues in The Myth Gap, a bigger us (less tribal), a longer now (not just short-term thinking), and a better good life “in which growth is less a story of increasing material consumption and more about finally growing up as a species.”

I commend Lisa Marshall’s book (she also happens to be my coach): Speak the Truth and Point to Hope: The Leader’s Journey to Maturity, in which she advocates for the wisdom of the sage or elder, which is less about chronological age and more about a state of mind, rather than what she calls “Peter Pan” leaders, who elevate the adolescent mindset to an art form. Less Mark Zuckerberg, more Atticus Finch.

In the same vein, some groups are now building on the work of Carol Dweck on Fixed vs Growth Mindset, and suggesting we need to cultivate a Benefit Mindset, a pro-social way of seeing the world in which leaders seek to maximise their contribution to a future of greater possibility.

Jane Goodall

Jane GoodallTo me it seems obvious that this is what we need more of, and yet it’s not what is highlighted in the media. It’s fantastic to see some true heroes occasionally getting headlines – like Jane Goodall, David Attenborough, Greta Thunberg – but their followings are tiny compared with Kylie, Khloe, Kourtney, and all the other badly-spelled Kardashians.

Humans love to measure and compare things, and money is a seductively simple metric. One dollar is much like any other dollar within the same currency, so it’s that easy to see that if Bezos is worth $131 billion while Gates is worth a mere $96.5 billion, Bezos is clearly better off. Money doesn’t require us to think about the relative merits of Bezos’s positive character traits vs those of Gates. With money, it’s all about the numbers.

But if we stop to think about it, does this mean that Bezos is the best person in the world, because he has the most money? Clearly not. He’s probably not even the smartest person in the world. Nor the kindest, or most generous, or most thoughtful. He’s just really, really good at making money, within our current neoliberal capitalist system.

And while that system has done a lot of good, it is also doing a lot of harm. So is that really what we want to aspire to?

So, Kylie, I watch with interest. I hope that your fortune brings you great happiness, and that you might also blaze a trail to show young women what a modern billionaire can look like, by putting it to good use in making the world a better place.

March 7, 2019

Capitalism and Consumerism

On a recent episode of The Big Bang Theory, Sheldon reveals to Amy his guilty secret – a large storage unit that contains everything he has ever owned in his life, including all his toothbrushes, racks of clothes and shelves of books, and his entire collection of sporting equipment (comprising the golf ball his brother once threw at him).

Sheldon

SheldonWe’re on Season 9 (I think) so the Sheldon character is 35 years old. Somehow, there didn’t seem to be all that much stuff in the storage unit. Some children have probably got through enough toys by the time they’re 10 to fill such a unit. (British research found that the average 10-year-old owns 238 toys but plays with just 12 daily.)

This got me wondering about just how much stuff a person gets through over the course of their life. Gratis of Google, I managed to find some weird and wonderful facts. In one lifetime, the average person will:

Eat approximately 35 tons of food (and grow around 590 miles of hair… and 2 metres of nose hair).

Use 2.72kg of lipstick if she’s a woman (and some men).

Walk the equivalent of 3 times around the world.

Drink 70,000 cups of coffee.

Spend £1.9 million (if British). (Surprisingly, this article claims a typical American university graduate spends less than a Brit – $1.8 million – with men earning on average $1 million more than women over a lifetime.)

The average American woman has 103 items of clothing in her closet, comprising 30 outfits—one for every day of the month. In 1930, that figure was 9 outfits. She considers 21 per cent of her clothes to be ‘unwearable’, 33 per cent too tight and 24 per cent too loose (according to a survey of 1,000 US women by ClosetMaid).

The average American woman has 103 items of clothing in her closet, comprising 30 outfits—one for every day of the month. In 1930, that figure was 9 outfits. She considers 21 per cent of her clothes to be ‘unwearable’, 33 per cent too tight and 24 per cent too loose (according to a survey of 1,000 US women by ClosetMaid).

The average British woman, over the course of a lifetime, will own 600 dresses, 400 pairs of shoes, 1,116 tops, 558 pairs of trousers and 372 cardigans.

The average American throws away 65 pounds of clothing per year (or 4,875 pounds over a 75-year lifetime).

Americans spend more on shoes, jewellery, and watches ($100 billion) than on higher education.

Over the course of our lifetime, we will spend a total of 3,680 hours or 153 days searching for misplaced items. Phones, keys, sunglasses, and paperwork top the list.

The average American will own 12 cars in their lifetime. That number is 9 for the average Brit. (Sheldon doesn’t drive, hence the lack of cars in his storage unit.)

Technology is definitely important for Sheldon, being a theoretical physicist and all. In fact, it’s the untimely demise of his trusty laptop that leads us to the whole storage unit storyline. There’s not much that’s average about Sheldon, but if he were a typical American, in a lifetime this website suggests that he would own:

Technology is definitely important for Sheldon, being a theoretical physicist and all. In fact, it’s the untimely demise of his trusty laptop that leads us to the whole storage unit storyline. There’s not much that’s average about Sheldon, but if he were a typical American, in a lifetime this website suggests that he would own:

Laptops: between 15.8 and 26.3

Tablets: 35.9

Mobile phones: 43.9

(and of course a lot of those purchases are not because the technology has failed, but because a better model has come out – at least Sheldon seems to be immune to this need to keep up with the latest model.)

Then there were some other stats that I couldn’t find online, so had to calculate for myself.

An average baby will go through 5,700–6,600 disposable nappies (aka diapers if you’re American) before it’s fully potty-trained. (Rather relieved Sheldon didn’t keep his.)

An average baby will go through 5,700–6,600 disposable nappies (aka diapers if you’re American) before it’s fully potty-trained. (Rather relieved Sheldon didn’t keep his.)

Assuming Sheldon is 35 and has been brushing his teeth since he was 1, that’s 34 years of toothbrushes, at 4 brushes per year, which equals 136 toothbrushes.

(I then got totally carried away calculating a lifetime’s consumption of hamburgers, with associated water usage and production of greenhouse gasses. But I realised I’d disappeared too far down the rabbit hole and hauled myself back. Maybe I’ll save those calculations for another blog. Oooh, I can tell you’re excited already.)

So what’s my point here?

The point is that over a lifetime we buy, use, and dispose of a LOT. This song by (appropriately) Garbage really brings vividly to life the image of a lifetime of stuff sitting and waiting for us in some imaginary attic, like a consumerist portrait of Dorian Gray, silent and incriminating.

All the garbage that you have thrown away

Is waiting somewhere a million miles away

Your condoms and your VCR

Your Ziploc bags and father’s car

Dark and silent, it waits for you ahead

So much garbage will never ever decay

And all your garbage will outlive you one day

(Etc. Hear it here.)

Do we really need all this stuff? Does it make us happy?

Some of it does, sure, and some we regard as necessary for a comfortable and convenient life. But everything comes with a cost, and I don’t mean just the financial one. Raw materials extracted, toxins and greenhouse gasses produced, and a long afterlife in landfill – these are the by-products we often don’t think about. As Daniel Kahneman says, we think What We See Is All There Is (WYSIATI), so once a possession passes out of our hands, to our minds it has disappeared. But it hasn’t.

I’ve got two ideas for apps, neither of which have any chance of catching on, but it’s an interesting thought experiment:

True Cost: you go into a store, and you’re interested in buying a cotton t-shirt. You point your smartphone at the barcode, and the phone brings up a rapid timelapse video of cotton growing, irrigation, pesticides, cotton-pickers, trucks, factories, sweatshop workers, night deliveries, and all the other things that had to happen to bring the t-shirt to this shop. Maybe it even shows you what the app deems to be a fair cost, if environmental degradation and fair wages were factored in, so you can compare this with the actual cost on the price tag and see if you still feel good about buying this item.

If We All: I’m still a bit vague on this one, but it’s something relating to the tragedy of the commons crossed with being the change you want to see in the world. You would tell the app something that you’re planning to do, like taking a cheap flight to the Costa Brava, and you then choose one of these options:

“if everybody did this”

“if x% of everybody did this”

“if I did this every day/month/year for the rest of my life”

…”what would be the impact?”

It could relate to something that you expect to have a negative impact, like that cheap flight or the sweatshop t-shirt or the hamburger, or it could be a positive action, like picking up three pieces of litter a day. You’d get some kind of an image that would show how your action would impact the world if multiplied up.

Any takers? I guess not. Never mind – I hope you get the point of what I’m saying, that if we could really see the full lifetimes of our stuff, before it comes into our hands and after it passes out of them, and also visualise the collective impact over time and space, we might make very different consumer decisions.

To tie this back to my recent theme of capitalism, we have been coerced into buying more than we need in order to fuel the capitalist machine. I highly recommend The Century of Self, about the rise and rise of advertising to hijack our human frailties and put them in service of consumerism. (Available for free on YouTube in 4 parts – Part 1 here.)

Some snippets from a recent article on Climate and Capitalism:

“Without steady growth, the [capitalist] economic system will proceed to wither away like a plant deprived of water and sunlight.”

“One of the problems facing capitalism throughout the nineteenth century was chronic overproduction. Businesses were producing goods for the market, but people tended to be frugal, self-sufficient, and were reluctant to spend their earnings on more and more consumer goods. More often than not, people tended to follow the ethic expressed in Christian Proverbs, “He that tilleth his land shall have plenty of bread: but he that followeth after vain persons shall have poverty enough … Remove far from me vanity and lies: give me neither poverty nor riches; feed me with food convenient for me.” For many Americans at that time, conspicuous consumption — overtly consuming and buying to display social status — was unseemly.”

“One of the problems facing capitalism throughout the nineteenth century was chronic overproduction. Businesses were producing goods for the market, but people tended to be frugal, self-sufficient, and were reluctant to spend their earnings on more and more consumer goods. More often than not, people tended to follow the ethic expressed in Christian Proverbs, “He that tilleth his land shall have plenty of bread: but he that followeth after vain persons shall have poverty enough … Remove far from me vanity and lies: give me neither poverty nor riches; feed me with food convenient for me.” For many Americans at that time, conspicuous consumption — overtly consuming and buying to display social status — was unseemly.”

“Capitalism has a systemic need to sell things. If people show no inclination to buy these things, then the capitalist machine will break down. To survive, capitalism must find ways — manipulation and seduction if necessary — to get people to buy more and more things that potentially have little or no relevance to their physical or spiritual well-being, or to that of their offspring. “

I wonder if it’s possible for us to return to nineteenth century simplicity? Stuff takes up a lot of headspace – earning the money to buy it, choosing it, buying it, transporting it, storing it, losing it, finding it, disposing of it. Many things no doubt add to our sum total of happiness, but many don’t. There is definitely a diminishing marginal return on acquiring more stuff once we have what we need, but the environmental impact doesn’t diminish along with the utility.

Enough is enough.

Enough is abundance to the wise. — Euripedes

P.S. Further to the debate whether a non-fan of capitalism is thereby a socialist/Marxist, in his own polemic way Umair Haque has a perspective that resonated with me.

February 28, 2019

Capitalism vs the Environment – How to End the War

The bluefin tuna is an amazing fish. According to the WWF website:

“Bluefin are the largest tuna and can live up to 40 years. They migrate across oceans and can dive more than 4,000 feet. Bluefin tuna are made for speed: built like torpedoes, have retractable fins and their eyes are set flush to their body. They are tremendous predators from the moment they hatch, seeking out schools of fish like herring, mackerel and even eels. They hunt by sight and have the sharpest vision of any bony fish.”

Unfortunately for bluefin tuna, they are also delicious. In 2013 it was reported that they had suffered a catastrophic decline in stocks in the Northern Pacific Ocean, of more than 96%. Even worse, most of the tuna being fished were juveniles that had not yet reproduced, threatening the future of the species.

Unfortunately for bluefin tuna, they are also delicious. In 2013 it was reported that they had suffered a catastrophic decline in stocks in the Northern Pacific Ocean, of more than 96%. Even worse, most of the tuna being fished were juveniles that had not yet reproduced, threatening the future of the species.

Money is playing a key role in the demise of the bluefin tuna. Mitsubishi, the car and electronics company, is not only investing heavily in tuna, they are stockpiling it in freezers in order to drive up the price. The rarer it gets, the more valuable it becomes. Once all the wild bluefins have gone, Mitsubishi’s frozen assets will be gradually released to the market at peak price.

Financially, there is every incentive to render the bluefin tuna extinct. Ethically, we have to question a system of incentives that produces such a result.

Yes, I know that over the last couple of hundred years capitalism has led to massive leaps forward in human wellbeing. Healthy competition has encouraged creativity and innovation. Rising wages have enabled huge rises in the standard of living. Philanthropy has improved the lot of many.

But I believe we need a new form of economics that will remedy the failings of capitalism as it is currently practiced. Many books have been written on this subject, so in this blog post I can only skim the surface of a much bigger topic, but here are a few reasons, right off the top of my head, why we need to take a long hard look at the monopoly of capitalism.

Externalisation of costs

John Paul Getty

John Paul GettyIf the goal of capitalism is maximisation of profit, then the incentive is to minimise costs. So if your company can exploit natural resources for next to free, then it will. As John Paul Getty said, “Formula for success: rise early, work hard, strike oil.” If the pure capitalist shows any restraint in the extraction of oil, precious metals, etc, it is not out of regard for the future, but to avoid flooding the market and hence reducing the price.

Likewise, if the capitalist can save the cost of disposing of unwanted by-products by dumping them into the air or a nearby river, he/she will do so, regardless of the consequences for humans and wildlife. Capitalism has no mechanism for discouraging exploitation or pollution, as they have no monetary cost, unless poor PR leads to reduced demand for the company’s goods. The blatant disregard of many companies for the environment has led to calls for the criminalisation of their degradation of our earth, air, and water – see Polly Higgins’ Ecocide campaign.

Civil society may organise protests to express their disgust at the environmental destruction, but companies will rarely respond until compelled to do so by government, which leads us to….

Corporate lobbying

(See earlier blog post on democracy.) Powerful industry lobbies can, and do, influence government through some strategically placed funding. They can also invest in…

Bad science

Nicotine isn’t addictive. Climate change doesn’t exist. Pesticides and herbicides do no harm (despite being poisons).

Koch Brothers

Koch BrothersIf you haven’t yet seen “Merchants of Doubt”, please do, or at least watch the trailer. It shows how there has been a concerted campaign of misinformation. Conservative think tanks with warm-and-cuddly-sounding names like Americans for Prosperity, Freedom Partners, Heritage Foundation, the Institute for Humane Studies, are funded by the rich and powerful to cast doubt on sound science and sow seeds of confusion in the collective public mind. (Oh, and those are just the think tanks funded by the Koch Brothers, described by The New Yorker as “longtime libertarians who believe in drastically lower personal and corporate taxes, minimal social services for the needy, and much less oversight of industry—especially environmental regulation.” There are many, many more such organisations.) If you ever see reports of a “study” claiming that something is safe – check who funded it, and then who funded them. Follow the money.

The mono-metric

“Perhaps what you measure is what you get. More likely, what you measure is all you’ll get. What you don’t (or can’t) measure is lost” – H. Thomas Johnson

So if all you measure is money – which is tempting, as money is so nice and easy to measure – then it’s unlikely that you will place much value on environmental stewardship, staff engagement, health, and wellbeing, unless and until they start to impact on your bottom line. Caring about staff wellbeing because sick days are impacting your profitability, or caring about the environment because ethical consumers are boycotting your products – that’s not really caring. That’s money.

You may tell me that we have BCorps and other companies that embrace the triple bottom line of people, planet, profit – and yes, this is true. But John Elkington, the man who coined the phrase “triple bottom line” recently issued a product recall on his concept, saying:

“Fundamentally, we have a hard-wired cultural problem in business, finance and markets. Whereas CEOs, CFOs, and other corporate leaders move heaven and earth to ensure that they hit their profit targets, the same is very rarely true of their people and planet targets. Clearly, the Triple Bottom Line has failed to bury the single bottom line paradigm. Critically, too, TBL’s stated goal from the outset was system change — pushing toward the transformation of capitalism. It was never supposed to be just an accounting system. It was originally intended as a genetic code, a triple helix of change for tomorrow’s capitalism, with a focus was on breakthrough change, disruption, asymmetric growth (with unsustainable sectors actively sidelined), and the scaling of next-generation market solutions.”

He goes on to point to companies that are genuinely embracing TBL as it was intended, but it is a short list. Profit still has a virtual monopoly as a corporate success metric.

Short term thinking

As I’ve said recently, I regard myself as essentially a utilitarian, curious about how we create systems that deliver the greatest good to the greatest number over the longest period of time. But this runs counter to short-term corporate reporting, and pressure to deliver maximum returns to shareholders. It’s encouraging to see organisations like Ceres working to “advance sustainability leadership among investors, companies and capital market influencers to drive solutions and take stronger action on the world’s biggest sustainability challenges, including climate change, water scarcity and pollution, and human rights abuses.” But there is still a long way to go. Extractive industries such as fossil fuels and minerals cannot, by definition, be sustained indefinitely. Industries such as fishing and farming have the potential to be sustainable, but are mostly not – current practices are leading to population crashes of many fish species, and to catastrophic degradation of the soil.

In too many ways, we are killing the goose that lays the golden egg of our future food supply.

So, what to do about all this?

Despite what some readers may think, I am not anti-capitalist, but I do believe that it is dangerous to have a neoliberal monoculture. Capitalism is well suited to some industries (technology, cars, electronics) but not to others (healthcare, nature conservation, social services).

To have a more resilient economy, and a more sustainable lifestyle, we need to embrace an ecosystem of types of currency that operate in different ways to motivate different kinds of behaviour. As Bernard Lietaer said:

To have a more resilient economy, and a more sustainable lifestyle, we need to embrace an ecosystem of types of currency that operate in different ways to motivate different kinds of behaviour. As Bernard Lietaer said:

“A complementary currency is a medium of exchange other than conventional money… I am talking about using this proven technology, characteristic of the information age, and using it to do things that do make a difference, by changing behaviour towards the environment and other people, encouraging people to do things that they wouldn’t do spontaneously… The alternative to using currency for this function is to create laws requiring or forcing people to do such things. With a currency you create a pull rather than a push, and that is a lot more attractive. You choose your objectives and specifically design your currency to achieve them.”

So, in my view, this is the way forwards – a multiplicity of currencies, some geographically based (such as the Brixton/Bristol/Totnes Pounds), some functionally based (Dashboard.Earth, Eco Coin, Women’s Coin, etc.) and so on, to create an interconnected web of financial-ish incentives to get more of the behaviours that will lead us towards a peaceful and sustainable future.

February 21, 2019

Bernard Lietaer, Visionary Economist

I was very saddened to hear of the passing away earlier this month of Bernard Lietaer. I never had the privilege of meeting him, but his work has had a profound effect on my thinking over the last year or so. Bernard’s wisdom will be much missed amongst people who are thinking hard about the future of money and attempting to design financial systems that promote sustainability and stability.

As he saw it, capitalism alone is not enough. Our current monoculture of capitalism makes the system volatile and vulnerable. We need a more multicultural approach to money, to build greater resilience into the system.

Further, the values that conventional economics promotes, such as short term thinking and competition, are suitable for some purposes, but not for others. So in those other areas, we can design complementary currencies better designed to motivate the behaviours we want to promote.

The big advantage of these complementary currencies is that they positively encourage certain behaviours in certain domains. The alternative would be increased legislation and central control. Better to have the “pull” dynamic of a complementary currency than the “push” of increased centralisation.

He goes into these points in greater detail in his video message for Bonmont Money. What follows is a paraphrased version of his words, as fast as I could type, and any errors are mine.

“I have a unique background, having been part of many situations that are usually mutually exclusive:

Central banker

Designer of Euro

Offshore currency fund manager

Academic

President of an electronic payments system

Worked with some of the largest multinationals on the planet

Worked with some of the poorest countries on the planet

These angles have given me the opportunity to see money in a way that wasn’t possible from the other angles.

Climate change is our number one problem. Other problems are: ageing societies; monetary instabilities under the current system; and structural unemployment because we can now have economic growth without jobs growth.

Conventional money is incompatible with sustainability for the following reasons:

Conventional money is incompatible with sustainability for the following reasons:

Short term thinking

The way money is created promotes the business cycle (boom and bust)

Users are all in competition with each other, which in some environments is healthy, but is not optimal in other environments

Social capital is not measured.

Nature does not look for maximum efficiency, it looks for a balance between efficiency and resilience. If you design only for efficiency, you have a fragile system. If you design only for resilience, you have stagnation. And conventional money is extremely efficient, hence very fragile.

None of the above challenges can be addressed within the current paradigm, i.e. with a single form of currency funded through bank debt. But they can all be addressed through complementary currencies. Money is the most powerful leverage point because it changes the motivation system.

A complementary currency is a medium of exchange other than conventional money. Loyalty schemes are the oldest form of complementary currency, e.g. airmiles, which are 40 years old. Shop loyalty schemes use a similar model. But these don’t do anything for society.

I am talking about using this proven technology, characteristic of the information age, and use it to do things that do make a difference, by changing behaviour towards the environment and other people, encouraging people to do things that they wouldn’t do spontaneously.

The alternative to using currency for this function is to create laws requiring or forcing people to do such things. With a currency you create a pull rather than a push, and that is a lot more attractive. You choose your objectives and specifically design your currency to achieve them. And it’s exportable. You can use it anywhere in the world.

The alternative to using currency for this function is to create laws requiring or forcing people to do such things. With a currency you create a pull rather than a push, and that is a lot more attractive. You choose your objectives and specifically design your currency to achieve them. And it’s exportable. You can use it anywhere in the world.

A key difference between the past and today is that more people on the planet have mobile phones than bank accounts. You can use mobiles to make global payments. That’s the future both for complimentary currencies, and for conventional money. Complementary currencies can be used on a scale that they have never been used in the past.

I want to pioneer this idea, to encourage experimentation, improvements, and diversity. And we need to also do work on the mainstream economy, and on the relationship between businesses and consumers.

Complementary currencies can create sustainable abundance. There is no reason there should be scarcity. We can have abundance, even for 10 billion people, if we rethink our money systems.

I am not suggesting that complementary currencies are enough to change everything, but changing our money is a necessary condition. Without changing the money system there is no chance of having, in ten to fifteen years, a planet that we want to live on.”

Those last words really resonated with me. Rethinking our money system may not be sufficient to secure our human future, but it is certainly necessary.

You may recall some of my earlier blogs reflecting on Bernard’s writings:

Money Makes the World Go Round?

Bernard, I’m sorry you didn’t live long enough to see the transformation of our global economy that you started, but we thank you for being a pioneer and pointing us in a better direction.

February 14, 2019

Capitalism and Beyond

Well, well, it has been an interesting week since I published my blog post about capitalism and what’s wrong with it.

First of all, let me say how grateful I am for having such a wide range of readers. When we hear in the media about the problem of isolated echo chambers and news bubbles… well, this blog’s audience is clearly both wider and wiser than that. And I celebrate you.

Secondly, I sincerely thank all those who took the trouble to write. You have definitely contributed to my knowledge and broadened my perspectives. You have also demonstrated something that we don’t see often enough in political circles, or at least in the US and the UK we don’t – a civilised exchange of views, in which we may agree to disagree, but at least both sides have listened, and responded rather than merely reacted. I appreciate it.

Thirdly, I notice how the emails of approval tended to be short (“Awesome thread of thought and well needed!” “a breath of fresh air in this pro capitalist nightmare” “wonderful work”), while the dissenting emails tended to be much longer, and in some cases conveyed desperate concern, as if I am a wayward child in danger of losing my immortal soul to the perils of communism. The word “Marxist” has come up more than once.

Fear not, dear reader. Just because I am not a fan of neoliberal capitalism does not mean I am a Marxist, socialist, communist, nor Corbynista.

Maybe this is part of the problem with our current thinking – the dualism that dictates that if we say we’re not one thing, the assumption is that we are its perceived “opposite”, while there is actually a whole spectrum of options.

Utilitarianism

UtilitarianismIf I were to apply any label to myself (and I’m not a big fan of labels, finding them over-simplistic), I would opt for “utilitarian”, with utilitarianism being defined as something like: “an ethical theory that determines right from wrong by focusing on outcomes. It is a form of consequentialism. Utilitarianism holds that the most ethical choice is the one that will produce the greatest good for the greatest number”. To that I would add “over the longest period of time, and relating to non-human as well as human actors”.

I am not going to be an apologist for Jason Hickel – he can do that for himself, as in this open letter disputing Steven Pinker’s much more rosy view of the current era. I don’t particularly appreciate Hickel’s tone – he adopts the condescension and faux politeness so often deployed in public arguments – but he makes some valid points to rebut Pinker’s critique. I’d specifically like to highlight this passage:

“Let me be clear: this is not a critique of industrialization as such. It is a critique of how industrialization was carried out during the period in question. If people had willingly opted into the capitalist labour system, while retaining rights to their commons and while gaining a fair share of the yields they produced, we would have a very different story on our hands. So let’s celebrate what industrialization has achieved – absolutely – but place it in proper context: colonization, violence, dispossession and all.”

Capitalism is not bad in itself – the fault lies in the way that it has too often been deployed (see Theory of Flaws).

Hickel’s main point is:

“What matters… is the extent of global poverty vis-à-vis our capacity to end it. As I have pointed out before, our capacity to end poverty (e.g., the cost of ending poverty as a proportion of the income of the non-poor) has increased many times faster than the proportional poverty rate has decreased.”

So yes, as a percentage, poverty is decreasing – but nowhere near as much as it could have done if we were genuinely trying to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number.

This led me to wondering: is the greatest good served by increasing income?

It might sound obvious that it would be, but I’ve been to villages where people have no electricity, extremely limited infrastructure, and a diet consisting of a narrow range of locally available foods – yet as night fell the forest would echo to the sound of laughter, rarely heard in the developed urban world. Was this just an anomaly, or could we be wrong in assuming a direct causal relationship between money and happiness?

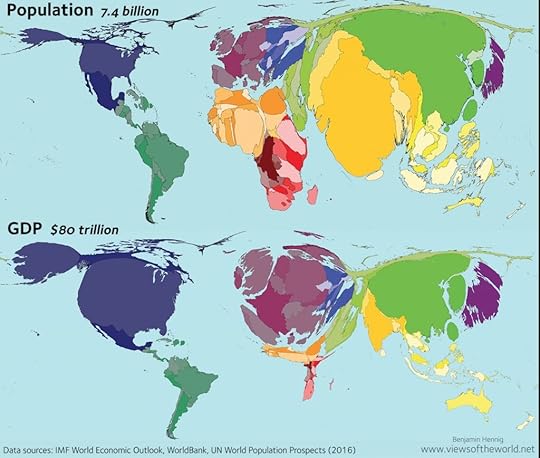

Overall, the evidence shows that yes, richer people are happier (lots of great data here). You may have heard of the Easterlin paradox where, in the US and Japan, reported levels of happiness appeared to stagnate despite an increase in average GDP per capita. However, according to this article, it appears that in Japan this was due to changes in the questions being asked about subjective happiness, so they weren’t comparing like with like, and in the US the plateau in wellbeing was due to the inequality of distribution – the increase in wealth was confined to the top few percent. At an individual level, there are of course happy poor people and miserable rich people, but in general it’s a lot easier to be happy if you have access to decent food, clean water, shelter, and healthcare.

Overall, the evidence shows that yes, richer people are happier (lots of great data here). You may have heard of the Easterlin paradox where, in the US and Japan, reported levels of happiness appeared to stagnate despite an increase in average GDP per capita. However, according to this article, it appears that in Japan this was due to changes in the questions being asked about subjective happiness, so they weren’t comparing like with like, and in the US the plateau in wellbeing was due to the inequality of distribution – the increase in wealth was confined to the top few percent. At an individual level, there are of course happy poor people and miserable rich people, but in general it’s a lot easier to be happy if you have access to decent food, clean water, shelter, and healthcare.

If you check out Dollar Street – which I strongly encourage you to do – you can see for yourself how the rest of the world lives. The team visited 264 families in 50 countries and collected 30,000 photos, then arranged them by level of income. So on the site you can zoom in on a family in Burundi living on $27 a month, and see their land, toys, stove, plates, water supply, cleaning materials, food, front door, bathroom facilities, shoes, teeth, beds, and so on. And a family living in the US on $4,446 a month. (Sadly it seems Jeff Bezos was not available to have his bathroom facilities photographed.) And many other countries and income levels besides.

One thing we notice from these photographs is that poor people generally have a lot less stuff than rich people. They have smaller houses, eat less, buy less, travel less, and have a lesser environmental impact (although are often in the front line of environmental disasters).

Yes, we want to end poverty – which, by implication, means we want poor people to have access to more food, more comfort, more of the good things in life. And here we run, yet again, into the inescapable logic of the IPAT equation:

Impact = Population x Affluence x Technology.

If the Affluence of developing countries is going to increase, and it’s unlikely that Technology can improve efficiency enough to counterbalance it, then if we want to hold Impact constant (or better still, reduce it) either we need to reduce Population, and/or we need to distribute Affluence more effectively in order to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number.

Oh wow, if capitalism was a controversial issue, now I’m really going in deep with population and wealth redistribution… Ah well, in for a penny, in for a pound. Let’s have this conversation! (to be continued)

P.S. I can’t not mention this. The other morning I was listening to BBC Radio 4, and after all the usual headlines about Brexit, Boris, etc. etc., the final headline was that insects are in catastrophic decline and could all but disappear by the end of the century, leading to the collapse of nature, which would be shortly followed by the extinction of humanity.

P.S. I can’t not mention this. The other morning I was listening to BBC Radio 4, and after all the usual headlines about Brexit, Boris, etc. etc., the final headline was that insects are in catastrophic decline and could all but disappear by the end of the century, leading to the collapse of nature, which would be shortly followed by the extinction of humanity.

Really?? The possible extinction of humanity within a century – the last headline??!

Or maybe I’ve just got my priorities all wrong. Clearly the imminent fiasco that is Brexit, or Boris Johnson’s latest utterances, are a lot more important than human extinction.

P.P.S. I’d be interested to hear your views on David Malpass, Trump’s nominee to head up the World Bank. I found his article in the FT, What I would do as the Next President of the World Bank, rather colonialist and patronising towards poorer countries, while also perpetuating the myth of the possibility of infinite growth on a finite planet. Oh, and until now I hadn’t realised that the president of the World Bank is ALWAYS an American, and in the couple of cases where the nominee is not, they are naturalised as US citizens first.

P.P.S. I’d be interested to hear your views on David Malpass, Trump’s nominee to head up the World Bank. I found his article in the FT, What I would do as the Next President of the World Bank, rather colonialist and patronising towards poorer countries, while also perpetuating the myth of the possibility of infinite growth on a finite planet. Oh, and until now I hadn’t realised that the president of the World Bank is ALWAYS an American, and in the couple of cases where the nominee is not, they are naturalised as US citizens first.

Might it not make more sense to have the bank headed up by someone who really, deeply understands the problems they are trying to alleviate? Maybe just occasionally?

February 6, 2019

How Capitalism is Failing

Oooh, I really feel I am straying into dangerous territory here. I have no doubt that many (or all) of you may not agree with some (or all) of the content of this blog post. If you don’t agree, please don’t storm off in a state of silent high dudgeon, or yell at me. The reasons that this blog series is called Big Questions is because they are a) Big, and b) Questions. If one viewpoint or another was obviously correct, they would be neither.