Roz Savage's Blog, page 19

June 20, 2019

On hiatus

I’m travelling for the next couple of weeks, so am taking a break from blogging. I’ll be back, refreshed and raring to go, in July.

See you then!

June 13, 2019

Farming and Fertilisers

“The soil is the great connector of lives, the source and destination of all. It is the healer and restorer and resurrector, by which disease passes into health, age into youth, death into life. Without proper care for it we can have no community, because without proper care for it we can have no life.”

― Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture

A couple of summers ago, I spent three weeks on Holy Isle, a small Scottish island owned entirely by a Buddhist community. Some people visit for a short course or retreat, normally for a week, while there are also long-term volunteers running the kitchens, gardens, and housekeeping. I was somewhere in between – a short term volunteer donating three hours a day to working in the gardens in exchange for a discount on my board and lodging.

There were many jobs that needed to be done in the several acres of garden, which would be shared out each day amongst the volunteers. I quickly became a specialist…. in shovelling pony poo. Ah, the glamour!

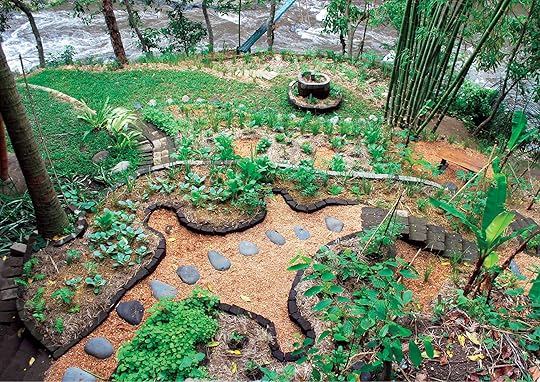

Vegetable garden, Holy Isle

Vegetable garden, Holy IsleThere is a small group of wild Eriskay ponies living on the island, descended from domestic animals, and their daily offerings are a rich source of nourishment for the vegetable beds. So each morning I would collect a wheelbarrow and a spade, and set out in search of manurish goodness. It’s really not as gross as it sounds – really just recycled grass, and not at all offensive. Once I’d exhausted the supply of poo within wheelbarrowing distance of the gardens, I’d collect seaweed from the rocky shore, or bracken from the hillsides. There were also separate compost heaps for the garden scraps, encased in chicken wire cages to keep rats away.

The end result of these various additions, suitably rotted down, was a rich, nutritious soil supplement, perfect for growing delicious vegetables. What we tend to rather disrespectfully call soil (UK), or dirt (US), is actually a complex ecosystem unto itself. It is estimated that a single teaspoon (1 gram) of rich garden soil can hold up to one billion bacteria, several yards of fungal filaments, several thousand protozoa, and scores of nematodes. Look out at your back garden, and marvel!

For many centuries, farmers knew that soil health was vital. Crop rotation ensured that nutrients were returned to the soil, and mitigated the build-up of pathogens and pests (see last week’s blog post on pesticides). But then we entered the modern era, and farming, like so many other areas of human activity, became about more, more, more, and faster, faster, faster. Cue artificial fertilisers.

Artificial fertilisers are not all bad. I’d like to make that clear at the start. The Haber process led to the Green Revolution, which increased the number of humans that could be fed from 1 hectare of land (2.47 acres) from 1.9 to 4.3. Millions have been lifted out of starvation over the last 40 years. Farmers working the poor soils in parts of Africa wouldn’t be able to feed their families without artificial fertilisers.

But there is a price to pay. Only 17% of the nitrogen used in fertilisers ends up in our food; the rest ends up in soil and water. And unfortunately nitrogen is also a great fertiliser for algae and bacteria. Fertiliser that ends up in lakes and the ocean causes massive blooms of algae, which use up the oxygen dissolved in the water, suffocating other species and creating dead zones. Right now, the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico is hitting the headlines, expected to expand to over 8,000 square miles this summer, fuelled by the Midwest floods that washed fertilizer into the Mississippi River, which then disgorged it into the Gulf. Chesapeake Bay has another large dead zone. Around the world, 405 dead zones have been identified, affecting an area of 95,000 square miles, about the size of New Zealand.

Further, producing fertilisers pollutes the atmosphere with greenhouse gases. The Haber reaction requires burning fossil fuels, which emit carbon dioxide. And other potent greenhouse gases, including nitrous oxide, are also released while making and using fertiliser.

So, can we have the best of both worlds – feed all the human mouths without damaging the soil and killing the oceans?

According to this BBC article:

“The truth is that it would be impossible to feed a growing global population using purely organic farming methods. And because organic farming is relatively inefficient (yields are on average 25% lower) compared to modern technological methods, vast new tracts of land would need to be used, which would further impact our forests and other ecological spaces.”

It turns out that different parts of the world need different solutions. African farmers need access to synthetic fertilisers if they are going to catch up with the rest of the world in crop production, as the soil they work with is so poor. But in Africa, as everywhere else, farmers should be encouraged to “micro-dose” their crops with exactly the right amount of fertilizer, which is more efficient financially, and minimises the problem of agricultural run-off creating dead zones.

In the US, Department of Agriculture (USDA) researcher Rick Haney advocates natural methods such as ploughing less, growing cover crops, and using biological controls to keep pests in check. He says:

“We were applying fertilizers and getting these big yields, so that system seemed to be working — until we began seeing, for example, the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico [created by algal blooms triggered by high nitrogen levels from fertilizer], and we started wondering if this was really working right. Are we putting on too much fertilizer? And the answer is, “Yes we are.” It’s like instead of feeding your children a balanced diet, let’s just feed them vitamins. That’s not going to work, is it?”

He also sees a win-win in using cover crops, old-style, to not only enrich the soil but also to sequester carbon as stipulated in the Paris Accord:

“We should never have soil bare — ever. Right now, farmers leave their fields bare for much of the year. If they would only plant a diverse, multi-species cover crop, just think of the carbon that we could sequester out of the atmosphere and put into the soil on the 150 million acres of corn and wheat land in this country. We could pull a phenomenal amount of carbon back into the soil, which is where it is supposed to be.”

At the domestic, individual level, what can we do?

We can buy organic. The UK’s Soil Association, in accordance with EU law (at least until Brexit), requires that certified organic food has been grown with no artificial fertilizers. It was a bit harder to make out what the USDA policy is, although it does state that “most” artificial fertilizers are prohibited.

We can choose to use only organic fertilizers on our gardens. If you don’t happen to have access to pony poo and seaweed, you can still use compost from garden waste, leaves, grass clippings, teabags, and even paper and cardboard. (Good tips from the Eden Project.)

We can convert lawns into flower borders or vegetable beds. Lawns can be intensive in terms of watering, mowing, and fertilizing, and they are food deserts for bees and other nectar-seeking insects. (12 reasons to get rid of your lawn here.)

In a couple of weeks I’m off to Schumacher College to do a course on Gardening as a Spiritual Practice. It may not include my particular specialisation of shoveling pony poo, but I’m sure I will learn a lot. I will report back in due course!

June 6, 2019

Pesticides: Can We Live Without?

In 1962 Rachel Carson published her seminal work, Silent Spring, warning that excessive use of synthetic pesticides, especially DDT, was killing wildlife and damaging human health. She also accused the chemical industry of spreading disinformation, and public officials of accepting the industry’s marketing claims unquestioningly. The book is widely credited with galvanising the environmental movement into existence.

Rachel Carson

Rachel CarsonThat same year, the Committee for Economic Development published An Adaptive Program for Agriculture, which promotes huge corporate farms at the expense of family farms. This report guided government policy for more than a decade – and arguably still does. (See: How America’s Food Giants Swallowed The Family Farms.)

The following year the President’s Science Advisory Committee published a report vindicating Rachel Carson’s research and assertions, thereby temporarily redeeming public officials from her accusations. In response, the National Agricultural Chemicals Association doubled its public relations budget, thereby absolutely confirming her accusations. This has now become a familiar strategy of selling bad ideas to the public. (See last week’s blog on “Molecules of Freedom”.)

I invite you to take a look at this timeline outlining the history of Big Chemicals’ War on Food. It’s interesting. Here are some highlights:

1986: Israel’s breast cancer rate drops 30 percent in women below the age of forty-four, just eight years after the country banned organochlorine pesticides.

1988: The US EPA finds seventy-four different pesticides in the groundwater of thirty-eight agricultural states.

1989: The conservative World Health Organization estimates that there are 1,000,000 pesticide poisonings in the world each year, resulting in 20,000 deaths.

1992: Tissue analysis demonstrates a substantial link between pesticides and breast cancer. The European Union approves the first government-enforced standards for organic production.

1994: Studies link organochlorine chemicals with male reproductive problems and breast cancer. Problems include a 50 percent drop in male sperm count in forty years.

Meanwhile, the arms race escalates:

1972: More than 250 pests worldwide are resistant to DDT.

1984: 447 species of insects and mites are known to be resistant to one or more pesticides; 14 weed species are resistant to one or more herbicides.

1997: More than 600 insects and mites are resistant to one or more pesticides. Approximately 120 weeds are resistant to one or more herbicides. Approximately 115 disease organisms are resistant to pesticides.

Pesticides are poisons. Homicide means killing a person. Genocide means killing lots of people. Pesticide means killing “pests”, and by “pest” we mean something else that wants to eat the same food we want to eat. The pest doesn’t know it’s a pest. It just wants its dinner.

Pesticides are poisons. Homicide means killing a person. Genocide means killing lots of people. Pesticide means killing “pests”, and by “pest” we mean something else that wants to eat the same food we want to eat. The pest doesn’t know it’s a pest. It just wants its dinner.

What does exposure to these chemicals entail? It’s not nice, for either the pests, the (often immigrant) workers administering them, or the lab animals. From PennState:

The toxicity of a pesticide is its capacity or ability to cause injury or illness. The toxicity of a particular pesticide is determined by subjecting test animals to varying dosages of the active ingredient and each of its formulated products…

Acute toxicity of a pesticide refers to the chemical’s ability to cause injury to a person or animal from a single exposure, generally of short duration. The four routes of exposure are dermal (skin), inhalation (lungs), oral (mouth), and eyes. Acute toxicity is determined by examining the dermal toxicity, inhalation toxicity, and oral toxicity of test animals. In addition, eye and skin irritation are also examined. Acute toxicity is measured as the amount or concentration of a toxicant– the a.i.–required to kill 50 percent of the animals in a test population…

The chronic toxicity of a pesticide is determined by subjecting test animals to long-term exposure to the active ingredient. Any harmful effects that occur from small doses repeated over a period of time are termed chronic effects. Some of the suspected chronic effects from exposure to certain pesticides include birth defects, production of tumors, blood disorders, and neurotoxic effects (nerve disorders).

And of course it’s not great for the planet either. According to the US National Institute of Health, “Over 1 billion pounds of pesticides are used in the United State (US) each year and approximately 5.6 billion pounds are used worldwide”. (The article goes on to say: “In many developing countries programs to control exposures are limited or non-existent. As a consequence; it has been estimated that as many as 25 million agricultural workers worldwide experience unintentional pesticide poisonings each year.”)

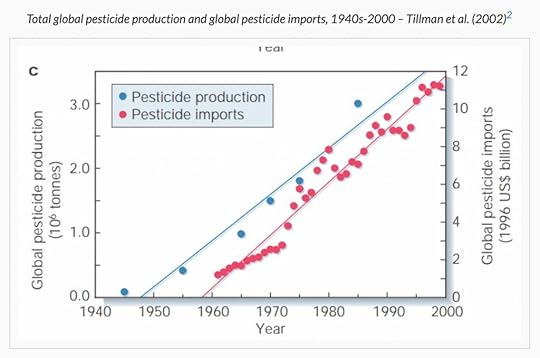

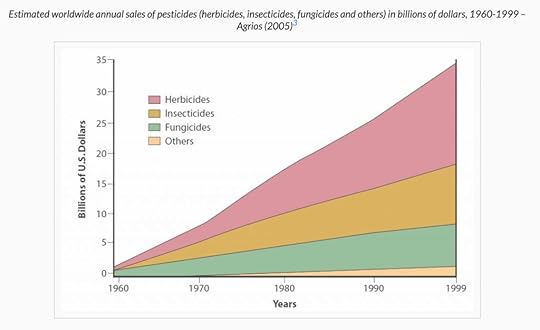

Ooh, time for some graphs, I think… (with thanks to Our World In Data).

Ah, you may say, but we need pesticides in order to produce enough food to feed everybody. And clearly, I am not advocating increasing world hunger.

The first step to reducing food poverty would be to stop wasting so much food. According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, around one third of global food production is wasted. Every year, consumers in rich countries waste almost as much food (222 million tonnes) as the entire net food production of sub-Saharan Africa (230 million tonnes).

And we don’t need to splurge pesticides around like there’s no tomorrow (literally). This study in Nature found that the losses resulting from a 50% reduction in pesticide use ranged from 5% to 13% of the yield obtained with the current pesticide use. (It also reports that two recent meta-analyses showed that the substitution of conventional high-input systems with organic systems would lead to 19% to 34% of yield loss – but see “stop wasting one third of food” point above.)

Can organic farming feed the world? According to this study by John Reganold, Regents Professor of Soil Science & Agroecology at the Washington State University, yes it can. He and his colleagues set out to see if we can feed an estimated world population of 9.6 billion people in 2050 without expanding the area of farmland we already use. They found that:

“Enough food could be produced with lower-yielding organic farming, if people become vegetarians or eat a more plant-based diet with lower meat consumption. The existing farmland can feed that many people if they are all vegan, a 94% success rate if they are vegetarian, 39% with a completely organic diet, and 15% with the Western-style diet based on meat.”

In other words, there is enough food for our need, but not for our greed, to quote Gandhi.

I’d like to leave the final word to a real-life farmer, Bob Quinn from Montana, who knows a lot more about this than I do, and believes it’s time to break our addiction to farm chemicals. Over to you, Bob.

Other Stuff:

Last night I spoke at the Royal Geographical Society in London at an event for World Oceans Day, coming up on 8th June. It was an honour to be speaking on the same stage as such oceanic superstars as Dr Sylvia Earle, Dr Callum Roberts, Dr Jon Copley, author Helen Scales, and Orla Doherty from the Blue Planet team. Thanks to all for a memorable evening.

May 30, 2019

Molecules of Freedom?

I will get back to my series on food production, I promise, but today I was sidetracked/gobsmacked by something I’ve just read in The Guardian, and needed to share.

Apparently the US energy department has rebranded fossil fuels as ‘molecules of freedom’.

I appreciate that energy can indeed improve quality of life in many ways, but energy from fossil fuels also has the potential to dramatically and negatively impact on your quality of life.

I’m assuming that the PR whizzkid who came up with the “molecules of freedom” tagline knew they were echoing the godfather of PR, Edward Bernays, who used the “torches of freedom” line to flog us something else that does us no good – cigarettes.

If you’re not familiar with this story, Bernays was hired just after World War I by the CEO of the American Tobacco Company, George Washington Hill, to help figure out how ATB could tap into the female half of the market. “If I can crack that market, it will be like opening new gold mine right in our front yard”, he allegedly said.

At the time, it was deemed unseemly for women to smoke in public. They were likely to be branded whores or harlots. A major cultural shift in public perception was going to be necessary. No doubt highly motivated by his $25,000 incentive, a vast sum at the time, Bernays came up with possibly the most audacious rebranding campaign in history.

On 31st March 1929, at the height of New York’s Easter Parade, a young woman named Bertha Hunt stepped out into the crowded Fifth Avenue and lit a Lucky Strike cigarette. The press had been informed in advance of her actions, and had been provided with leaflets containing relevant information (propaganda). What they did not know was that Hunt was Bernays’s secretary and that this was the first in a series of events that was aimed at getting women to smoke. Bernays proclaimed that smoking was a form of liberation for women, their chance to express their strength and freedom.

On 31st March 1929, at the height of New York’s Easter Parade, a young woman named Bertha Hunt stepped out into the crowded Fifth Avenue and lit a Lucky Strike cigarette. The press had been informed in advance of her actions, and had been provided with leaflets containing relevant information (propaganda). What they did not know was that Hunt was Bernays’s secretary and that this was the first in a series of events that was aimed at getting women to smoke. Bernays proclaimed that smoking was a form of liberation for women, their chance to express their strength and freedom.

The great irony was that Bernays was using sexual liberation as a form of control. “Torches of freedom” actually enslaved countless women into nicotine addiction.

The capitalist objective was served, with Lucky Strikes doubling its sales between 1923 and 1929. But at what cost to human health and wellbeing? Well heck, hospital bills boost GDP too, so what’s not to love about that? (sarcasm).

(There is a good little 5 minute film by HowStuffWorks that explains more about this story, including the clever use of colour messaging to manipulate the market. I also highly recommend a series called The Century of Self, which starts with Bernays and traces the rise and rise of PR/marketing, and hence materialism, throughout the 20th century, changing us from citizens into consumers, conditioned to satisfy our wants rather than our needs. It’s powerful viewing.)

So what is the moral of the story? I think it’s this.

When somebody tries to sell you something on the basis of “freedom”, get sceptical. While you may win a “freedom to” (smoke/burn fossil fuels), you may also lose a “freedom from” (disease/climate change). Follow the money, and see who stands to benefit. I’d can almost guarantee it’s not you.

May 23, 2019

Hi from Skye

A very short blog post this week, as we’re staying with our dear friend Dr Iain McGilchrist at his lovely home on the Isle of Skye.

Iain is a rare blend of enormous intelligence in both heart and head – do check out this talk he gave at Schumacher College in Devon. Or this short illustrated talk also gives a good overview of his work on the divided brain, and how our current world is becoming dangerously left-brain-dominant.

Right, I’m off for a hike through some glorious (if slightly damp) Scottish scenery. Enjoy!

May 16, 2019

Monoculture: Economically Efficient, Ecologically Disastrous

Economically, reducing the number of types of crops that a farmer grows makes perfect sense. Just as production lines increase the efficiency of manufacturing, focusing on one crop, with one method of harvesting, and one customer or middleman to deal with, increases the efficiency of food production.

Ecologically, though, monoculture is a disaster. Growing the same crop on the same piece of land, year after year, exhausts the soil of the nutrients used by that crop, which then have to be artificially replaced with fertilizers, usually artificial. When the land becomes damaged beyond use, we have to clear fresh land to replace it. Degraded topsoil has less organic matter, which is needed to retain rainwater, so it becomes prone to run-off into streams and rivers, causing further damage.

Large areas of one crop are susceptible to damage from weeds, insects, blights and bacteria – which we label “pests” for competing with us for food – so we then wage chemical warfare on these “pests”, although things that are bad for pests are often bad for humans too (California Jury Awards $2 Billion To Couple In Roundup Weed Killer Cancer Trial).

Large areas of one crop are susceptible to damage from weeds, insects, blights and bacteria – which we label “pests” for competing with us for food – so we then wage chemical warfare on these “pests”, although things that are bad for pests are often bad for humans too (California Jury Awards $2 Billion To Couple In Roundup Weed Killer Cancer Trial).

Nature is adaptive and resilient, and finds ways to resist our chemicals – so we up the ante, and the increasing chemical load pollutes groundwater, which then flows to other places, affecting ecosystems far from the intended target.

Monoculture also contributes to climate change; with specific regions of the world specialising in specific crops, in order to create the variety of foods demanded by consumers we have to shuffle large quantities of food around the world by road, air, and sea. The more food travels, the more it requires plastic packaging to keep it fresh, and/or energy-intensive refrigeration.

It wasn’t always like this. The earliest records of crop rotation date from 6000 BC (according to Wikipedia). A single piece of land would be used for different crops over a cycle of a number of years, and sometimes left fallow to allow the soil to recover. This system was infinitely sustainable, ensuring the soil’s nutrients were restored and rebalanced, never exhausted. Now we call it permaculture.

My favourite description of permaculture is in the third section of Michael Pollen’s The Omnivore’s Dilemma, where the author visits Joel Salatin’s Polyface Farm in Virginia, an inspiring (though not perfect) example of an almost self-sustaining ecosystem, in which farmer and nature cooperate rather than compete, and nothing is wasted.

For example, their guiding principles include:

INDIVIDUALITY: Plants and animals should be provided a habitat that allows them to express their physiological distinctiveness. Respecting and honoring the pigness of the pig is a foundation for societal health.

INDIVIDUALITY: Plants and animals should be provided a habitat that allows them to express their physiological distinctiveness. Respecting and honoring the pigness of the pig is a foundation for societal health.

COMMUNITY: We do not ship food. We should all seek food closer to home, in our foodshed, our own bioregion. This means enjoying seasonality and reacquainting ourselves with our home kitchens.

NATURE’S TEMPLATE: Mimicking natural patterns on a commercial domestic scale insures moral and ethical boundaries to human cleverness. Cows are herbivores, not omnivores; that is why we’ve never fed them dead cows like the United States Department of Agriculture encouraged (the alleged cause of mad cows).

EARTHWORMS: We’re really in the earthworm enhancement business. Stimulating soil biota is our first priority. Soil health creates healthy food.

Their website goes on to illustrate:

“The laying hens scratch through the dung, eat out the fly larvae, scatter the nutrients into the soil, and give thousands of dollars worth of eggs as a byproduct of pasture sanitation. Pastured broilers in floorless pasture schooners move every day to a fresh paddock salad bar. Pigs aerate compost and finish on acorns in forest glens. It’s all a symbiotic, multi-speciated synergistic relationship-dense production model that yields far more per acre than industrial models.”

I also highly recommend The Running Hare: The Secret Life of Farmland, a lyrical (and occasionally earthy) account of a year in a life of a small field that its owner resolves to farm the old-fashioned way, and witnesses the return of wildlife in abundance, contrasted with the barrenness of the surrounding fields owned by farmers he dubs “The Chemical Brothers”.

Can we feed the world with organic/permaculture farming?

Apparently, yes. And the benefits – for biodiversity, for the oceans, for future generations of humans – are not just significant, they are vital. If we continue with intensive agriculture, we may only have 60 more harvests left – and that is just looking at the soil side of the equation. If insect populations continue to plummet as a result of pesticides and climate change, we may lose our pollinators.

The good news is, we can all contribute to the solution by growing food in our garden, on our balcony or windowsill. We’re moving house this summer, from the town to the country – and I can’t wait to put to use my new book, Veg in One Bed. Even when I was on my boat, I was able to grow fresh sprouts (sponsored by Sproutpeople), which are delicious and packed with healthy goodness.

It’s not difficult to grow some of your own food, and it all helps – less plastic, less environmental degradation, more health and more connection to nature. What’s not to love about that?!

Other Stuff:

I received this very interesting correspondence after last week’s blog post, Eating Ourselves Out Of House, Home, And Planet:

Please know this email comes from my heart and I have the utmost respect for you! Also, I might be misunderstanding the point you made–my apologies up front if I’ve done that.

In my opinion the passages you quoted from Quinn is part of the “neo-Malthusian” movement, that began way back with Paul Ehrlich and Population Bomb in 50s and 60s. It’s a form of neo-colonialism. Without going into the weeds, here’s what’s true: The human population increases when there is food/health INSECURITY rather than food/health security. Population isn’t growing bc there’s plenty of food. When people don’t have food/health security they have larger families–it’s in the data. All developing countries have high tfr (total fertility rates) bc they are poor and have little future security. Educate them, give them a future and food/health security and the tfr always drops. Most importantly, educate the girls (because boys by default have first crack at education when it first becomes available). Educated girls then have options aside from child bearer and water carrier. Education can’t come without first having food/health taken care of. So, food security isn’t driving population growth–poverty is. My sense is that Quinn is confused on this point, and he falls into the neo-Malthusian trap that (in Malthus’ case) was cloaked misogyny and misanthropy. I’m not saying Quinn was that, but Malthus certainly was that. (The character Scrooge was based on him.) The world population is going to plateau at 10-11 billion by 2100. That plateau only comes with economic development of poor countries. 80% of the world will live in Africa and Asia by 2100. Africa doesn’t have an overpopulation problem–it has a poverty problem.

I can very much see the logic in it, even while feeling faintly depressed at the thought of 10-11 billion humans with all of our consumption, pollution, and general taking-up-of-space.

I’m absolutely all in favour of education and equality (economic and gender being particularly relevant here), and I’m appreciative of the correlation between the education of girls and a drop in birth rates. I do, though, remain tremendously concerned about the impact of our increasing population combined with increasing consumption. The inescapable logic of the IPAT equation again…. (Impact = Population x Affluence x Technology).

May 9, 2019

Eating Ourselves Out Of House, Home and Planet

“Famine isn’t unique to humans. All species are subject to it everywhere in the world. When the population of any species outstrips its food resources, that population declines until it’s once again in balance with its resources. Mother Culture says that humans should be exempt from that process, so when she finds a population that has outstripped its resources, she rushes in food from the outside, thus making it a certainty that there will be even more of them to starve in the next generation. Because the population is never allowed to decline to the point at which it can be supported by its own resources, famine becomes a chronic feature of their lives.”

When I first read Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit, back in about 2004, it completely disrupted my perception of the relationship between humans and the other sectors of nature. It was as if it lifted a veil of delusion, and I understood the world in a way I hadn’t before. For the first time, I really grasped how humans have sought to dominate nature, and how unsustainable a strategy this is.

When I first read Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael: An Adventure of the Mind and Spirit, back in about 2004, it completely disrupted my perception of the relationship between humans and the other sectors of nature. It was as if it lifted a veil of delusion, and I understood the world in a way I hadn’t before. For the first time, I really grasped how humans have sought to dominate nature, and how unsustainable a strategy this is.

By “Mother Culture” in the passage above, Quinn refers to the collective myth that we humans demonstrably hold; that we are superior to nature, that nature is there to serve our purposes, and that we are in some magical way exempt from the rules of nature.

He isn’t saying that famine relief is a bad thing – clearly it is the “civilised” and compassionate thing to do – but he is saying that, at the macro level, it doesn’t address the systemic problems that created the famine in the first place. It’s giving a man a fish to feed him for a day, rather than helping him relocate to a place with more fish, or better still, finding ways (education, contraception, etc) to help him and his family produce fewer human mouths in need of fish.

Quinn goes on to say:

“You need to take a step back from the problem in order to see it in global perspective. At present there are five and a half billion of you here, and, though millions of you are starving, you’re producing enough food to feed six billion. And because you’re producing enough food for six billion, it’s a biological certainty that in three or four years there will be six billion of you. By that time, however (even though millions of you will still be starving), you’ll be producing enough food for six and a half billion—which means that in another three or four years there will be six and a half billion. But by that time you’ll be producing enough food for seven billion (even though millions of you will still be starving), which again means that in another three or four years there will be seven billion of you. In order to halt this process, you must face the fact that increasing food production doesn’t feed your hungry, it only fuels your population explosion.”

And of course in the closed system that is Planet Earth, the more humans there are, the less space is left is left for other species. Sadly, this is one zero sum game that isn’t going away. (Even if you’re into colonising other planets, it’s going to be a very long time before they becomes a viable source of food.) As you can see from the graphic, humans now require more than 50% of Earth’s land surface area for our homes and our food production. Every extra square mile that we claim for ourselves means one less square mile for rainforest, wetlands, savannah, and other vital strongholds of biodiversity.

It’s not just the amount of space that we take up – it’s how we use it. Over the coming weeks I’m going to take a look at modern food production, covering such topics as:

Monocultures

Chemical farming and agribusiness

Run-off and dead zones

Soil degradation

Food shipping (and plastic packaging)

Animal cruelty (feedlots and slaughterhouses)

Climate change

Deforestation and palm oil

Displacement of subsistence farmers (US, Africa etc)

GMO

These are quite big and heavy subjects, so I’m going to be keeping these blog posts shorter. I’ve been getting a bit long-winded of late (!), so am downsizing this series of food-related posts into bite-sized (Chicken Mc)nuggets.

A final comment from Quinn/Ishmael, pulling no punches:

“This is considered almost holy work by farmers and ranchers. Kill off everything you can’t eat. Kill off anything that eats what you eat. Kill off anything that doesn’t feed what you eat.

It IS holy work, in Taker culture. The more competitors you destroy, the more humans you can bring into the world, and that makes it just about the holiest work there is. Once you exempt yourself from the law of limited competition, everything in the world except your food and the food of your food becomes an enemy to be exterminated.”

Other Stuff:

I’m off to Wales tomorrow for a Sisters weekend retreat. Very much looking forward to connecting with some amazing women, with lots of walking and talking on the agenda. Especially looking forward to exploring several miles of Glyndwr’s Way, even if it is named after a warrior idolised by the Welsh for taking on the English!

May 2, 2019

And Now For Some Good News

Here in Windsor the sun is shining (for now) and spring has sprung, with this season’s show of bluebells being the best I’ve ever seen. So it felt like time for a more upbeat blog post after all the seriousness and passings away that have featured heavily of late.

I’m also going to be unashamedly focused on my home country, the UK, in this blog post, because for once, in the midst of our Brexit morass, we have some good news.

Greta Thunberg has been in town, and along with the rest of her cohort that have been taking part in school strikes, she has shaken things up, and shamed her seniors into action. (I recommend her full speech, where she pulls no punches – for example: “we [my generation] probably don’t even have a future any more. Because that future was sold so that a small number of people could make unimaginable amounts of money. It was stolen from us every time you said that the sky was the limit.”)

An attentive audience including Michael Gove (Sec of State for Environment) and Ed Miliband (former Sec of State for Energy and Climate Change)

An attentive audience including Michael Gove (Sec of State for Environment) and Ed Miliband (former Sec of State for Energy and Climate Change)Extinction Rebellion used civil disobedience to powerful effect, opening the door to conversations with politicians who are finally pulling their heads out of the dark hole that is Brexit and facing up to the climate emergency.

The Committee on Climate Change has come up with a plan on how the UK can reach net zero carbon emissions by 2050 – maybe even sooner.

Of course, talk is cheap, but it really does feel as if change is afoot in our small corner of the world. We may be a minnow compared with the great white sharks of China, India, Russia and the US, but along with the rest of the Carbon Neutrality Coalition we have a key role to play in demonstrating that developed countries can realistically set an intention for net zero.

Words may not be sufficient, but they are necessary. And now they must lead to action.

Other Stuff:

If you’re into nature documentaries (I nearly wrote “nature porn”, and then I remembered my mother reads this blog) then you will love Earth From Space, a stunning new series from the BBC that marries up satellite imagery with footage shot from the ground, to dazzling effect.

We don’t know how much is left for the world as we know it, so enjoy it while you can.

April 25, 2019

Polly Higgins, Lawyer for the Planet

I’m sad to say that the world has lost yet another great and courageous advocate for a better future. I was honoured to call Polly Higgins a friend, and her death at the age of just 50 has, I’m sure, left a gap in the many lives that she touched during her passionate campaign to have ecocide recognised as an international crime, ecocide being the wilful destruction of our ecosystems by corporate or government action.

I first met Polly back in November 2009, when we both went to an event organised by a mutual friend at the Fortnum & Mason store in London. We quickly discovered that we had a lot to talk about, so as soon as we could we sloped off to find somewhere where we could speak more easily. We ended up in a very odd establishment – a vast restaurant with hardly anybody in it, with waiters who seemed to have only the vaguest idea what waiting tables involved. We concluded that the restaurant was probably a cover operation for some nefarious activity, but we stayed anyway, and talked for hours about our shared concern for the future of Earth.

We spent time together again the next month, at the COP15 UN conference in Copenhagen, hoping for a fair and binding deal on climate change, which sadly failed to materialise, and the following year I stayed with Polly and her husband, Ian, at their home in Islington. I don’t remember now exactly how long I stayed, but as I had no fixed abode during those ocean rowing years, I suspect it was longer than a houseguest should. I do specifically recall that for whatever reason I was short of clothes, and Polly loaned me some of her own. That’s what she was like – a true friend who would literally give you the clothes off her back.

I have many more personal memories that I could share, but I will instead focus here on Polly’s work and legacy.

Having started out her professional career as a barrister, which could have led to a lucrative life of ease and comfort, Polly answered the call to adventure by becoming an advocate for the Earth. She combined her legal training with her environmental passion to home in on the idea of criminalising wilful ecological damage as the most powerful tool to prevent further destruction. She later discovered that this was in fact a reboot of an earlier idea that arose in the idealistic period after World War II. Her book, Eradicating Ecocide, was published in 2010.

As well as having a formidable intellect, Polly also had a huge heart, and a strong spiritual life. At TEDxWhitechapel, at the last minute she discarded her prepared remarks about ecocide, and instead talked on the theme “Dare to be Great” – definitely walking the talk when it came to daring greatly. This was a phrase that had come to her while she walked barefoot in a downpour in the New Forest, and became her call to action, as well as the title of her third book. She challenged all of us to become the leaders we have been waiting for, rather than waiting in vain for a hero. She saw this recognition of our interdependence as crucial to the shift to a sustainable future – interdependence between humans, and interdependence between humans and nature. She identified three core values:

The interconnectedness of all life

The sacredness of all life

The love of life

“[My work] is driven by a huge amount of love for people and planet,” she said. “It’s the love that drives me forward. I love this earth, and it is utterly untenable that we keep on destroying it.” She saw no role for hatred or blame, only love. It’s not about being a protester, she said – it’s about being a protector.

And this, I think, is a rare and precious quality. Christiana Figueres, an equally impressive woman, also has it: the ability to speak both from the head and from the heart, having the knowledge but also the wisdom, combining clear sightedness with compassion.

In terms of her legacy, she reminds me of Rachel Carson who, like Polly, was claimed by cancer at way too young an age, but left us with powerful writings that both sound an alarm bell, and point the way to a better future.

The last few weeks I have started to feel more like an obituary writer than a blogger. I sincerely hope that it will be a long while before I need to pay tribute again to a late, lamented spirit like Bernard Lietaer, Barbara Marx Hubbard, or Polly.

At the same time as we are losing the older guard of luminaries from the environmental world, it also feels as if there is a passing of the baton to the young people, like Bella Lack and Greta Thunberg, who have the moral authority as representatives of the generation that will bear the brunt of climate change and the sixth mass extinction.

We will, of course, miss having Polly with us in person, but her work will be carried on by her team at Earth Protectors. You can sign up to become an Earth Protector yourself – your donation (min 5 Euros) goes to help fund the campaign by small island states pursuing the enactment of ecocide law through the International Criminal Court.

More resources on Polly:

Interview (transcript) with Dan McTiernan

April 18, 2019

Barbara Marx Hubbard: The Revolutionary Evolutionary

Sometimes deaths come in spates. In 2016 we lost several famous rock stars, including David Bowie, Prince, Leonard Cohen and George Michael. I hope 2019 isn’t turning into the year that we lose too many rock stars of the future/visionary world. In 2019 Bernard Lietaer passed away, and last week I heard that Barbara Marx Hubbard had died. She was 89 years old, admittedly, but had been in excellent health until a swollen knee led to a chain of events that ended with her life support being turned off.

I never met Barbara, as I never met Bernard, and yet both had a significant influence on my worldview, particularly on how I perceive the future and what needs to happen to make it both peaceful and sustainable. As you have hopefully gathered from recent blog posts, I am extremely doubtful that we can solve our problems from within the same structures that have created them, and believe that we need a new narrative about what it means to be human in the 21st century: as Alex Evans puts it in The Myth Gap, we need a narrative that embodies “a larger us, a longer now, a better good life”.

I never met Barbara, as I never met Bernard, and yet both had a significant influence on my worldview, particularly on how I perceive the future and what needs to happen to make it both peaceful and sustainable. As you have hopefully gathered from recent blog posts, I am extremely doubtful that we can solve our problems from within the same structures that have created them, and believe that we need a new narrative about what it means to be human in the 21st century: as Alex Evans puts it in The Myth Gap, we need a narrative that embodies “a larger us, a longer now, a better good life”.

If you’re not familiar with Barbara’s work, I will attempt to do it some small amount of justice in this blog post, and I’d also encourage you to watch one of her talks, like this one. Her central thesis was that, after millions of years of evolution on Planet Earth, we are the first species to be aware of the process of evolution, so it is incumbent on us to use that awareness to consciously manage our future evolution.

She has sometimes been disparagingly referred to as part of the New Age movement, but I think this is to do her a disservice. She brought immense intellectual curiosity to her work, with great questions being her particular stock in trade.

A turning point in Hubbard’s life was the end of World War II and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “What was all this power for?” she wondered.

In 1952, her father took her to see President Eisenhower in the Oval Office. “What can I do for you, young lady?” he asked casually. “Mr. President,” she said, “I have a question for you. What is the meaning of our new powers that is good?”

He looked startled, shook his head, and said, “I have no idea.”

Then we better find out, she thought, and the quest for a vision of the future equal to our new power became the driving question of her life.

This question also led her to meet her husband. She was a student at Bryn Mawr in Pennsylvania when she took a year out in Paris. One day, while hanging out in a Parisian café, she struck up a conversation with an artist, a man by the name of Earl Hubbard. She asked him the questions she had been asking everyone, the questions inspired by Hiroshima: “What do you think is the meaning of our new power that is good, and what do you think is your purpose?” This young man had an immediate answer: “I’m seeking a new image of man commensurate with our power to shape the future. When a culture loses its story, loses its self-image, it loses its greatness. The artist has to find a new story and until it is expressed by artists, we won’t be able to bring our culture to fruition.” Her only response was a small voice in her mind that said, “I’m going to marry him.”

And she did. And went on to have five children as a housewife in Connecticut. But she needed more than domestic bliss, and started reading books in search of answers.

It started with Maslow’s Toward a Psychology of Being. He said that every self-actualizing person has one thing in common: a chosen vocation they found intrinsically self-rewarding. Here she found a great clue to conscious evolution: the need to find innate life purpose that transcends mere selfish desire to prevail, with vocation being a vital way of directly experiencing the evolutionary impulse.

Then came Teilhard de Chardin. She wrote later: “This was the real opening. I could tell from his Law of Complexity/Consciousness — the understanding of God in evolution rising to higher consciousness, freedom and more complex order, that my own impulse to grow, to be more, to realize my potential was not the musings of a neurotic housewife, but rather, it was the universe unfolding in me as me.”

Then came Buckminster Fuller, who told us that we have the resources, technologies and know-how to make of humanity a 100% physical success without destroying our environment.

It was February 1966 when she had a life-changing vision while walking on a frosty hill near her Connecticut home. She wrote:

“I asked the universe a question: “What is Our Story? What on Earth is comparable to the birth of Christ?” What I meant by that is the Gospels were such an amazingly effective story. What could be our story comparable in power to that?

Suddenly, my mind’s eye penetrated the blue cocoon of earth and lifted me up into the utter blackness of outer space. A Technicolor movie turned on. I felt the earth as a living organism, heaving for breath, struggling to coordinate itself as one body. It was alive! I became a cell in that body.

In the next few minutes I saw conscious evolution as the next stage of evolution itself. It is the evolution of evolution from unconscious to conscious choice. I realized that we are literally in a crisis of birth of the next stage of our evolution. We are outgrowing the womb of self-conscious humanity and planet-boundedness. We can learn to restore the Earth, free ourselves from scarcity and move forward into an immeasurable future as a co-evolutionary co-creative species. Like a newborn infant, we innately know how to do this…. when we have the right story to guide us.”

She dedicated herself to learning the story and to telling it in every way that she could. She believed that Maslow was right, in that a true vocation is a key to participation in conscious evolution.

“I see vocation as the enfolded implicate order, the process of creation localizing and unfolding in each of us as our own passion to create. Once that happens the Consciousness Force internalizes and we enter the process of conscious self-evolution. We become conscious evolutionaries.”

She saw the essential task of conscious evolution as being “to learn how to be responsible for the ethical guidance of our evolution. It is a quest to understand the processes of developmental change, to identify inherent values for the purpose of learning how to cooperate with these processes toward chosen and positive futures, both near term and long range.”

She boiled this down to “the three C’s:”—new cosmology, new crises, and new capacities.

Our new cosmology is the story that science has revealed about where our universe came from, about the extraordinary process of which we are a part. It is important, Hubbard wrote, because it gives us “a new sense of identity, not as isolated individuals in a meaningless universe but rather as the universe in person” Our new crises, she explained, are those potentially catastrophic global issues we face, such as climate change. In light of evolution’s trajectory, these are reframed as a “natural but dangerous stage in the birth process” of our next evolutionary stage. Hubbard points out that there have always been crises as part of the process—mass extinctions, ice ages, and so on—but never before have we had advance warning of our pending self-destruction and therefore had the opportunity to do something about it. We are shifting, she wrote, from “reactive response to proactive choice.”

The third piece in Hubbard’s triad, new capacities, are recently developed powers such as biotechnology, nuclear power, nanotechnology, cybernetics, artificial intelligence, and artificial life. She acknowledged that in our current state of “self-centred consciousness” these are potentially hazardous, and yet, she suggests, they may be exactly what we need for the next phase of our evolution. She cautioned against acting out of fear and prematurely destroying these new technologies. The task of conscious evolution is rather to “guide their capacities toward the emancipation of our evolutionary potential.”

She saw a special role for women in the emerging new consciousness: “An evolutionary woman is activated by an inner impulse to create, to love more, be more, create more and give more… The evolutionary woman is able to love what’s being born in her – the creative feminine – and able to love giving her gift to the unknown world.”

I will give the last word to BMH:

“Perhaps we are indeed coming to the end of this world, to the end of civilization, the end of separate self consciousness as we have known it. And this is good. We are being instructed by Failure – the failure of war to win, the failure of consumerism to satisfy, the inevitable rise of the seas in response to global warming brought on in part at least by human destruction of nature. All of these evolutionary drivers may indeed be the impulse needed to jump our species to a higher order, or to self destruction.”

She lived a long and prolific life, and many will miss her, but she has left a huge legacy of thought leadership, books, and presentations. Although I don’t particularly believe in a heaven as such, I nonetheless like to imagine that her spirit is now somewhere where she can ask great questions to her heart’s content, and get the answers she so enthusiastically sought.