Roz Savage's Blog, page 21

January 31, 2019

Elinor Ostrom and Avoiding the Tragedy of the Commons

Recently I’ve been looking at democracy and its shortcomings as a system of governance. I’ve also looked at some alternatives. This week I’d like to look at my front-runner for a viable form of governance that could nicely balance autonomy and control: self-organising management, created, implemented, governed, and maintained by the people most affected.

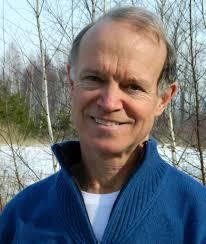

Elinor Ostrom

Elinor OstromThe real pioneer of this approach was Elinor Ostrom, the first – and so far only – woman to win the Nobel Prize for Economics. Born in 1933, into a family of limited means, she paid her own way through college, and although initially employers were interested only in her abilities in shorthand and typing, she went on to do her PhD at UCLA and joined the faculty at Indiana University. (I strongly encourage you to check out this great bio and video interview – on the website of UBS, my former employers!)

Her particular fascination was with – and ultimately her Nobel Prize would be awarded for – the management of the commons. The theory of the tragedy of the commons was that individual users acting independently according to their own self-interest would behave contrary to the common good of all users by over-exploiting the shared resource through their collective action. However, Ostrom noticed, this wasn’t always so. Many such potential situations around the world managed to avoid tragedy through active cooperation.

After extensive interviews with farmers and peasants to gather case studies from many countries, and discussion of their findings with scholars across many disciplines, Elinor and her husband arrived at eight principles:

1. Define clear group boundaries.

Specifically, who are the people concerned, and what is the shared resource, under discussion?

2. Match rules governing use of common goods to local needs and conditions.

There is no one-size-fits-all. Rules should be determined by local people in accordance with local ecological needs.

3. Ensure that those affected by the rules can participate in modifying the rules.

Participatory decision-making is vital.There are all kinds of ways to make it happen, but people will be more likely to follow the rules if they had a hand in writing them. (And see the recent crowdsourced constitution in Iceland for an example of this principle in action. It remains be seen if a successful exercise conducted in a country of around half a million people can be scaled up to larger countries.)

4. Make sure the rule-making rights of community members are respected by outside authorities.

Commons rules won’t count for anything if other nearby and/or higher authorities don’t recognise them as legitimate.

5. Develop a system, carried out by community members, for monitoring members’ behaviour.

Once rules have been set, communities need a way of checking that people are keeping them. Commons don’t run on good will, but on accountability.

6. Use graduated sanctions for rule violators.

Ostrom observed that the commons that worked best didn’t just ban people who broke the rules, which tended to create resentment. Instead, they had escalating systems of warnings and fines, as well as informal reputational consequences in the community.

(This system works well in the Balinese community Banjars – see this article, which is worth reading in its entirety. Especially relevant here: “the main form of punishment meted out by the Banjar is not a Rupiah fine, but ostracism – the exclusion from the Banjar of someone who refuses three times in a row to respect the community decisions. And the reason given why such ostracism is so serious is “when they have an important family ceremony, like a cremation, marriages, or coming of age rituals, then nobody will give Time for helping them in the preparations.” In short, depriving someone of Time from the community is considered the ultimate retribution.”)

7. Provide accessible, low-cost means for dispute resolution.

When issues come up, resolving them should be informal, cheap and straightforward. That means that anyone can take their problems for mediation, and nobody is shut out. Problems are solved rather than ignoring them because nobody wants to pay legal fees.

8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

8. Build responsibility for governing the common resource in nested tiers from the lowest level up to the entire interconnected system.

Some things can be managed locally, but some might need wider regional cooperation – for example an irrigation network might depend on a river that others also draw on upstream. The concept here is not so much hierarchical, as fractal, where each unit is self-contained, but also contained within a larger unit.

A classic example of Ostrom’s principles in action was her field research (no pun intended!) in a Swiss village where farmers tend private plots for crops but share a communal meadow to graze their cows. While this would appear a perfect model to prove the tragedy-of-the-commons theory, Ostrom discovered that in reality there were no problems with overgrazing. This was because of a common agreement among villagers that no one was allowed to graze more cows on the meadow than they could care for over the winter—a rule that dates back to 1517.

One critique is that the communities that Ostrom studied all had the quality of being a “community of mutually vulnerable actors”. If one actor has a disproportionate amount of power, they will not be very motivated to participate. And, in reality, power is rarely evenly distributed. To draw a parallel, the happiness and wellbeing of the Nordic countries have often been attributed to their relatively small populations, coupled with homogeneity and equality. Citizens are willing to pay high taxes in exchange for excellent education, healthcare, and pensions, because the assumption is that all their fellow citizens are contributing more or less equally, and that those being helped are, essentially, “people like us”. This does not hold true in all countries.

One critique is that the communities that Ostrom studied all had the quality of being a “community of mutually vulnerable actors”. If one actor has a disproportionate amount of power, they will not be very motivated to participate. And, in reality, power is rarely evenly distributed. To draw a parallel, the happiness and wellbeing of the Nordic countries have often been attributed to their relatively small populations, coupled with homogeneity and equality. Citizens are willing to pay high taxes in exchange for excellent education, healthcare, and pensions, because the assumption is that all their fellow citizens are contributing more or less equally, and that those being helped are, essentially, “people like us”. This does not hold true in all countries.

Another critique is that not all governance can take place at such a local and devolved level. Some policies simply have to operate at a national level in order to make sense. The question has been raised: “Globalization has a major impact on local-level resource management through such mechanisms as the creation of international markets. Can a theory of the commons, based on local-level cases, be scaled up to deal with the complexity of communities and social-political networks?” Although arguably it would be beneficial in many ways to return to smaller scale communities and economies (see Bill McKibben’s Eaarth, in which he argues for the greater resilience of “small is beautiful”), it looks close to impossible from where we are now, but it’s not impossible that we could yet create a nested, or fractal, system of communities, in which national policies equate to the sum total of local policies.

In Journey to Earthland (which I highly recommend – the free download is available at GreatTransition.org), Paul Raskin speaks of a future utopia called Earthland, whose political philosophy resting on the principle of constrained pluralism, comprised of three complementary sub-principles: irreducibility, subsidiarity, and heterogeneity. Irreducibility affirms his One World philosophy: the adjudication of certain issues (such as climate change) necessarily and properly is retained at the global level of governance. Subsidiarity means the importance of Many Places: the scope of irreducible global authority is sharply limited and decision-making is guided to the most local level feasible. Heterogeneity grants regions the right to pursue forms of social evolution that chime with their democratically determined values and traditions, constrained only by their obligation to conform to globally mandated responsibilities.

In Journey to Earthland (which I highly recommend – the free download is available at GreatTransition.org), Paul Raskin speaks of a future utopia called Earthland, whose political philosophy resting on the principle of constrained pluralism, comprised of three complementary sub-principles: irreducibility, subsidiarity, and heterogeneity. Irreducibility affirms his One World philosophy: the adjudication of certain issues (such as climate change) necessarily and properly is retained at the global level of governance. Subsidiarity means the importance of Many Places: the scope of irreducible global authority is sharply limited and decision-making is guided to the most local level feasible. Heterogeneity grants regions the right to pursue forms of social evolution that chime with their democratically determined values and traditions, constrained only by their obligation to conform to globally mandated responsibilities.

At its heart, whether we look to Ostrom or Raskin or Bali or some other model, it seems self-evident to me that any healthy system of governance needs to embody and promote trust, legitimacy, and transparency. This seems a far cry from what many western democracies have become, corrupted by big money, big egos, and hidden machinations. One great challenge of constitutional reform is that, by definition, the people who have the power to create the change are the very ones who have benefited from the status quo.

Unless the pitchforks – or a global political Spring – are coming….?

January 24, 2019

Carpe Diem

Today I’m digressing from my current series on Big Questions to talk about something much more personal – the loss of a friend and longtime supporter, Karen Morss of Emerald Hills, California.

Life, love, and longevity are much on my mind this week, as I was up in Yorkshire to celebrate my mother’s 80th birthday (happy birthday, Mum!). Mum has lived a sensible life of moderation, and despite two hip replacements she is still in good health and quite capable of walking five or even seven miles at a time. I trust she will be with us, fit and active, for many years to come.

Her good fortune was brought into sharp relief by some sad news from the US. Karen Morss had been a friend of mine since 2008, when we were both featured in the same issue of the Bucks restaurant menu, a Silicon Valley institution, and were connected by our mutual friend Jamis MacNiven. Karen had planted an organic lemon orchard in her backyard, and was supplying various local businesses, including Bucks.

With Karen, 2008

With Karen, 2008I was about to set out on my second attempt on the Pacific. Karen had come up with the lovely idea of naming each of her forty trees after a woman who inspired her, and honoured me with an invitation to be one of her Lemon Ladies. I spent an enjoyable afternoon at her home, painting a terracotta tile which would become the name tag for “my” tree. Over the years after that, Karen would always find a way to get some lemon marmalade and plum jam to me before each voyage, no matter where in the world I was, to augment my onboard supplies. I found many creative and delicious uses for the preserves, and it always gave me a glow to eat a bit of California sunshine and think of the kindness behind the gift.

She would also often send me a link to a news story from her iPad, and had an uncanny knack for knowing what I would find interesting.

I last saw Karen Morss at a brunch hosted by my wonderful friends, Angela Hey and John Mashey, at their home in Portola Valley, back in late October. She seemed as lively and energetic as ever, but said she hadn’t been feeling too great, so she left early.

Karen and Lucy, 2008

Karen and Lucy, 2008The following day she emailed me: “It was so nice to see you both yesterday. You are both looking well. Life is agreeing with you! I’m sorry for the quick departure. I’m off to the chiropractor this morning. My back was really hurting yesterday but I really wanted to see you.”

On 9th December I pinged her an email to see how she was doing, and a couple of hours later received this reply: “I have some bad news. I’ll know more by end of the week. More tests this week. Looks like cancer has spread throughout everything.” We exchanged a few more emails, mine expressing sympathy and support, hers affectionate and positive, accompanied by emojis of hearts and lemons.

While I was up in Yorkshire last week, I realised I hadn’t heard from her in a while, so I dropped her an email. A few hours later I received this reply from Karen’s husband:

“This is Dave responding. Karen passed away December 30. Her ashes are now in the lemon orchard with the ashes of Lucy, Sophie and Tosha (their dogs)”.

It was such a shock. I had to read the message several times before I could believe it. How could somebody so alive be gone? And so swiftly?

Me and “my” lemon tree

Me and “my” lemon treeSo this blog post is my tribute to Karen Morss. All those years ago, when I wrote two versions of my own obituary – an exercise that changed my life – Karen is exactly the sort of person I would have turned to for inspiration. She lived several lifetimes in one – tech entrepreneur, pilot, flight school owner, author, lemon lady. Everything she did, she did with gusto and high standards. She did me the honour of writing an article for the very first edition of our Sisters magazine, When Lemons Give You Life, which I very much encourage you to read to get a sense of the essence of Karen.

My thoughts are especially with Dave, and with all who knew and loved Karen.

I take this sad loss as a reminder to live life to the fullest, because it is a privilege to be alive. Life should be cherished, because we never know how long we have.

January 17, 2019

Democracy Revisited

After my last blog post, on democracy and its shortcomings, I had originally planned to plough on into a discussion on capitalism, as another bright and breezy topic (!). But there has been some interesting feedback and discussion on democracy, and I’d like to share a few more ideas that have emerged since my last post, mostly around global governance.

GLOBAL PLANETARY AUTHORITY

A friend drew my attention to Angus Forbes’s call for a Global Planetary Authority. On their website they say:

“After 250 years of the increasingly destructive Anthropocene, a separate authority needs to be set up to protect and enhance the natural assets of our incredible planet for the next 1000 years. We now run a biosphere. We have joined mother nature in the driving seat. We are the first species ever to do so and we are doing a terrible job because we are not properly organised… So we have to create a global authority that is fit for purpose, designed specifically to do the job of protecting a biosphere.”

To this end, the VoteGPA campaign is looking to garner one and a half billion votes, saying that this will give them the mandate to create a GPA.

Somehow the GPA makes me think of the Jedi Council…

Somehow the GPA makes me think of the Jedi Council…I agree with Forbes on the following points:

the relationship between humans and nature has fundamentally shifted, and we would be disingenuous to pretend that we don’t have the power to destroy our biosphere, or at least materially alter it for the worse (the book Defiant Earth is a gut-punching wake up call on this topic)

attempting to avoid ecological disaster through on a nation state basis, as in the UN conferences on climate change where delegates seek to protect their national interests, is not working – we need to recognise that, no matter what country we come from, we all live on the same planet, connected by our oceans and our atmosphere.

However, I have a lot of reservations about the feasibility and conceptual basis of a GPA. On the feasibility, even if he manages to gather the one and a half billion votes, I don’t see the Putins or Trumps of this world bowing down meekly and allowing the GPA to levy taxes on their citizens to support its work.

And conceptually, it feels very “dominator” to me – a small central authority of “experts” imposing its will on the rest of the world. Isn’t this the kind of oligarchy that we’re trying to move away from?

I fundamentally believe that we need to move out of our current dominator culture and into a mindset of partnership, in which we acknowledge that everything and everybody is connected, and gather together to co-create a better future.

WORLD POLITICAL PARTY

I am a member of the Great Transition Network, and we’re currently having a discussion around a proposal for a WPP written by Heikki Patomäki, a Finnish political scientist. The idea is to create a transnational association dedicated to democratic principles and processes that, under an umbrella of shared principles and aims, spawns a vast network of semiautonomous nodes at all levels.

I am a member of the Great Transition Network, and we’re currently having a discussion around a proposal for a WPP written by Heikki Patomäki, a Finnish political scientist. The idea is to create a transnational association dedicated to democratic principles and processes that, under an umbrella of shared principles and aims, spawns a vast network of semiautonomous nodes at all levels.

I agree with him that there is an urgent need for political action on a global level, that “shared problems require shared action”, and that “A sustainable global future will be impossible without a fundamental shift from the dominant national mythos to a global worldview”.

Most of the critiques that I have read so far centre on the fact that a WPP would face the same problems that undermine the effectiveness of the national political parties we already have – that no country is willing to put itself at a competitive disadvantage by doing what is necessary rather than what is economically expedient.

SIMPOL

We all take the leap together

We all take the leap togetherA couple of alternative models have emerged from the discussion. The Simultaneous Policy concept (SIMPOL) consists of a series of multi-issue global problem-solving policy packages, each of which is to be implemented by all or sufficient nations simultaneously, on the same date, so that no nation loses out. Citizens who join the campaign can contribute to the design of those policies and to getting them implemented. By joining the campaign, citizens agree to ‘give strong voting preference in all future national elections to politicians or parties that have signed a pledge to implement SIMPOL simultaneously alongside other governments, to the probable exclusion of those who choose not to sign’. This pledge (the ‘Pledge’) commits a politician, party, or government to implement SIMPOL’s policies alongside other governments, if and when sufficient other governments have also signed on, and SIMPOL only gets implemented if and when all or sufficient nations have similarly signed up.

The idea is getting some traction: in the UK where SIMPOL is most developed, at the last national election in 2017 over 650 candidates from all the main political parties signed the Pledge. Of those, 67 are now Members of Parliament, which is about 10% of all UK MPs. Elsewhere, there are 14 pledged MPs in the Irish Parliament and 11 in the German Bundestag, plus a handful of MPs in the EU parliament, and in Australia, Argentina, and Luxembourg.

Clearly there’s a long way to go before the concept can be proven, and looking at the past it may seem a stretch to believe that humans could act in such a concerted fashion, but maybe we will be united by crisis.

THE GOOD COUNTRY

Another member of the Great Transition Network mentioned The Good Country, which launched a few months ago.

The feelgood video on their website ends with the invitation: “If you’re a member of the human race first, and a citizen of your own nation second…. If you’d like governments to focus a lot more on collaborating, and a little less on competing…. If you see a great future for humanity, if only humanity could learn to work as one… then you’re one of us. Welcome home to the Good Country.”

All sounds good, but how does it work? According to their website, “Research shows that at least ten percent of the world’s population shares the Good Country’s values and its world-view. That’s 760 million people, the third most populous nation on earth, and nobody even knew it was there. Until now.”

They believe their AI platform will enable ‘big conversations’ in which citizens can comment, discuss and ultimately rate recommendations so as to inform the creation of crowd-policy. “Normally, this approach is only possible in small focus groups, but the AI technology behind Remesh makes it possible to “take the temperature” of the Good Country’s entire population simultaneously – doing away with traditional binary voting systems and removing the need for a government bureaucracy.”

So it’s more grassroots in its approach than the GPA or the WPP, and feels more “partnership” than “dominator”, which I like. But can it access and influence the big levers of power, like political parties and multi-national corporations? It’s too soon to tell.

THE THEORY OF FLAWS

While I was at Yale in 2012, I had a number of conversations with Professor Richard Foster at the School of Management, and he shared with me his Theory of Flaws – that all systems created by humans are necessarily flawed, because humans are flawed. It’s hard to fault the logic.

To aspire to perfection may, then, be unrealistic. But when we look at the current fruits of our systems of governance – separatist, self-protecting, combative, short-termist, ego-driven – it seems that we have plenty of room for improvement.

I’ll leave you with a final thought – or more of a question, really. What is the disruption that will lead to a form of governance better suited to creating the kind of future that we want?

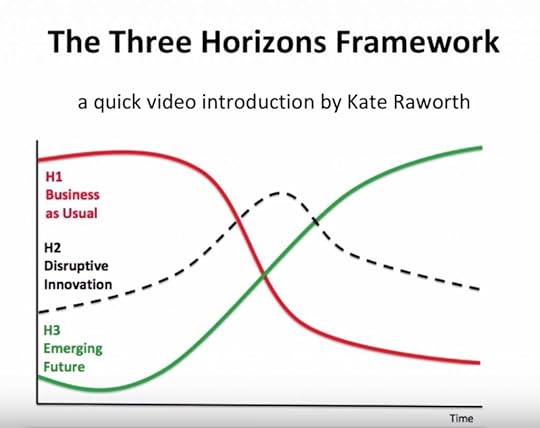

Check out this video on Bill Sharpe’s Three Horizons Thinking, presented by the wonderful Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics (and it is to my regret that Kate is the only woman featured on this blog post – and even then she is presenting a man’s theory – where are all the women’s voices on this topic?!).

Check out this video on Bill Sharpe’s Three Horizons Thinking, presented by the wonderful Kate Raworth, author of Doughnut Economics (and it is to my regret that Kate is the only woman featured on this blog post – and even then she is presenting a man’s theory – where are all the women’s voices on this topic?!).

Horizon 1 is business as usual, a degenerative and divisive economy. Horizon 3 is the emerging future, a regenerative and distributive economy. We may accept that we want to move from H1 to H3. And in between we have H2, which is the rogue element of disruption that can give us a sufficient jolt off our current track that we can jump onto a new one. Some potential disruptions get co-opted by H1, and we get more of the same. But some enable us to leap to H3.

What will it take for us to move beyond dreaming of better governance, and actually make it happen?

January 3, 2019

Big Questions: Democracy for the Future

Wishing you a very Happy New Year! I hope your 2019 has got off to a serene start.

I’d like to launch 2019 with an ambitious series of blog posts that take a look at some of our global systems that have served reasonably well for a long time, but now it may well be worth asking if we can create something better. Let’s start with a little thing like democracy. (Yikes!)

In their book Crowdocracy, Alan Watkins and Iman Stratenus set out a list of democracy’s fundamental shortcomings:

Democracy is not majority rule.

A study looked at more than 20 years of data, and found that “the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.” But it was a very different story for the richest 10% of Americans. If the wealthy are against a law, it has a zero percent chance of being passed. If they are in favour of it, it has a 70% chance of being passed.

A study looked at more than 20 years of data, and found that “the preferences of the average American appear to have only a minuscule, near-zero, statistically non-significant impact upon public policy.” But it was a very different story for the richest 10% of Americans. If the wealthy are against a law, it has a zero percent chance of being passed. If they are in favour of it, it has a 70% chance of being passed.

And of course there is gerrymandering, the practice of manipulating the boundaries of electoral districts to favour the party in power. And the first-past-the-post system means that the number of seats a party wins rarely bears any relation to the number of votes it received. In 2015 the British Conservative government won the election with only 37% of the vote – the rest of the electorate voted for a different party, or didn’t vote at all. The Greens and UKIP got more than 5 million votes (out of an electorate of 46 million), but got only one seat apiece, while in Scotland the Scottish National Party received 50% of the votes but won 95% of the seats. In different years in the US, Al Gore and Hilary Clinton polled 51% and 56% respectively, but still lost. (Source: Wikipedia)

Small wonder that a lot of people don’t feel that their government represents their views and interests. Odds are, it doesn’t. It has been said that we get the politicians we deserve, but sometimes we don’t even get the ones we voted for.

And we haven’t even talked about Facebook, Cambridge Analytica, or the Russians…

Supreme power is held by the lobby and vested interests.

There is a strong correlation between your budget and your chances of electoral victory. In the Senate in 2014, 91% of the candidates who spent the most money, won. The sums of money involved are vast, and most of it comes from the richest 0.2% of the population. The climate-change-denying Koch brothers expected to spend $889 million on the 2016 presidential election, and they probably did. Do we really believe that donors expect no favours in exchange for their generosity, or that a politician is immune to the hope of future largesse?

There is a strong correlation between your budget and your chances of electoral victory. In the Senate in 2014, 91% of the candidates who spent the most money, won. The sums of money involved are vast, and most of it comes from the richest 0.2% of the population. The climate-change-denying Koch brothers expected to spend $889 million on the 2016 presidential election, and they probably did. Do we really believe that donors expect no favours in exchange for their generosity, or that a politician is immune to the hope of future largesse?

In the 5 years to 2015, the 200 most politically active companies in the US spent $5.8 billion influencing the government, and received $4.4 trillion in taxpayer support – so their money was well spent. In the UK, the lobbying industry is estimated to be worth £2 billion. The late Nye Evan MP referred to “gastronomic pimping”, in which MPs are handsomely wined and dined in the hope of future favours. In his first week as London Mayor, Boris Johnson was invited to attend a dinner party along with 19 senior bankers, at which he pledged to do his utmost to ward off banking regulation in the City.

Even our former Prime Minister David Cameron called it out, saying: “It arouses people’s worst fears and suspicions about how our political system works, with money buying power, power fishing for money and a cosy club at the top making decisions in their own interest.”

Jimmy Carter was even more blunt: “It violates the essence of what made America a great country in its political system. Now it’s just an oligarchy with unlimited political bribery being the essence of getting the nominations for president or being elected president.”

Democracy fosters superficial and inadequate focus on the issues.

It sometimes feels as if, when one party says white is white, the other party will say white is black, just to be contrary. As H. L. Mencken pithily summed it up: “Under democracy, one party always devotes its chief energies to trying to prove that the other party is unfit to rule – and both commonly succeed, and are right.”

It sometimes feels as if, when one party says white is white, the other party will say white is black, just to be contrary. As H. L. Mencken pithily summed it up: “Under democracy, one party always devotes its chief energies to trying to prove that the other party is unfit to rule – and both commonly succeed, and are right.”

The night that Barack Obama was inaugurated, a group of high-powered Republicans met and agreed to “show a united and unyielding opposition to the president’s economic policies.” The unrelentingly adversarial nature of politics in both the US and the UK makes it increasingly hard to find the optimal outcome for the country, when the major parties refuse to agree with each other on anything at all. And let’s not even talk about the yah-boo-sucks schoolyard jeers of Prime Minister’s Questions.

Democracy fosters division.

US: Republicans vs Democrats. UK: Brexit vs Remainers. QED.

Politicians are struggling under the weight of escalating complexity.

The world is a complicated place. It was complicated enough in the era of Yes, Minister (Sir Humphrey on classic form here), and it is exponentially more complicated now. Cabinet appointments, in the UK at least, are based less on relevant expertise than on whether one’s star is rising (Foreign Secretary) or falling (Culture). And sometimes a minister has just got the hang of, say, Transport, when they get whisked to the Exchequer, and have to master their brief from Day 1, with zero tolerance for failure.

Rather them than me.

Democracy is not a meritocracy.

If it were, we wouldn’t need spin doctors.

Human nature being what it is, and as we’re mostly too time-starved to do our due diligence, our choice is more likely to be determined by appearance, demeanour, and media-friendliness than by character and policies.

And in certain countries, already having bucketloads of cash doesn’t hurt either.

Politicians don’t have a voice either – their vote is “whipped”.

(For non-UK readers, the “whip” isn’t actually a physical whip (although it may sometimes have the same effect) – he/she is a political official appointed by their party to ensure their Members of Parliament vote the way they are supposed to.)

Politicians have many competing loyalties, and sometimes they may be left with no choice but to toe the party line.

(from my Yale class on political courage)

(from my Yale class on political courage)

The system facilitates self-interest and scandal.

Possibly because most politicians get paid less than their peers in banking or industry, they often feel entitled to garner a few perks on the side, of varying degrees of legitimacy – from lucrative “revolving door” roles when they leave office, to blatantly fraudulent expense claims.

Possibly because most politicians get paid less than their peers in banking or industry, they often feel entitled to garner a few perks on the side, of varying degrees of legitimacy – from lucrative “revolving door” roles when they leave office, to blatantly fraudulent expense claims.

Since leaving office in 2007, Tony Blair has accumulated an estimated £80 million in earnings, while Bill and Hillary Clinton made $240 million between 2000 and 2015. Vladimir Putin is estimated to be worth $200 BILLION, which would make him the richest person on earth – and we probably don’t even want to speculate how he came by his money.

Arguably they are entitled to their wealth – politics is a brutal business, and the CEO of Time Warner makes $50 million a year just for running a Fortune 100 company, not a country – but you can’t help wondering whether this tarnishes their motivation.

So one way and another, democracy has its issues. There are, of course, many forms ofdemocracy – Switzerland, Singapore, and the Nordic countries have some interesting models. China isn’t a democracy, but until recently didn’t seem any the worse for it.

The main point I’m making is not that democracy is failing, but that we shouldn’t simply assume that democracy is the ultimate form of political governance. There may possibly be something better.

Watkins advocates crowdocracy, using technology to enable universal participation in governance. He draws inspiration from Iceland’s crowdsourcing of its new constitution in 2012 in the wake of the financial crash. Although I very much concurred with his analysis of the failings of democracy in its current form, I wasn’t convinced by the practicalities of his vision for crowdocracy. It seemed likely to me that most people would still be disengaged from the process, while the country would be run by the kind of committee-loving people who usually get to run things.

Holacracy was fashionable for a while, especially in Silicon Valley. The concept is of a self-organising structure with minimal management, maximum autonomy, in a kind of biomimetic nested structure. The shoe company Zappos is one of its chief proponents. It may have some potential, although I’m not aware of any countries attempting it at a nationwide level.

The next stage beyond holacracy would seem to be Teal organisations, as advocated by Frederic Laloux. The three foundations of the Teal organization (lifted from this review) are:

Self-management: To operate effectively based on a system of peer relationships, without the need for either hierarchy or consensus.

Wholeness: People no longer have to show only their “professional” self, or hide doubts and vulnerability. Instead, a culture invites everyone to bring all of who we are at work.

Evolutionary purpose: Instead of trying to predict and control the future, the organization has a life and a sense of direction of its own. Everyone is invited to listen in and understand what the organization wants to become, what purpose it wants to serve.

Could something like this ever work at a national level? It sounds like a terrifying prospect, with visions of anarchy and chaos immediately leaping to mind.

In a perfect world (which doesn’t exist) we would all be terribly sensible people who simply want the greatest good for the greatest number, as described in the fictional country of Herland. If we lived in a system that trusted us to be good and decent people, would we live up to that level of responsibility? But wouldn’t we have had to already reach that level of responsibility in order to create that system? Our social contracts and sense of community would need to be a lot stronger than they are now.

So it all becomes rather cart-and-horse.

I’d be really interested to hear what you think. What great ideas do you have for the form of governance you would like to see in your country?

Other Stuff:

I spent the last few days of 2018 doing my review of the year. I describe the full process in my article for the Sisters magazine (and my dear friends Anja and Ishika also describe theirs). If you didn’t get around to doing an annual review before the end of the year, it’s not too late. In fact, there’s never a bad time to do a review – a bit of a life audit is always a great idea!

December 20, 2018

December 13, 2018

Wicked and Wise

You might have come across the idea of wicked problems. These are not “wicked” in the sense of the Wicked Witch of the West, but rather wickedly complicated to resolve. Many problems facing the world today fit into “wicked”, as defined by Alan Watkins and Ken Wilber in their book, Wicked and Wise: How to Solve the World’s Toughest Problems.

A wicked problem is multi-dimensional

A wicked problem has multiple stakeholders

A wicked problem has multiple causes

A wicked problem has multiple syndromes

A wicked problem has multiple solutions

A wicked problem is constantly evolving (and is therefore never fully solved)

Sound like some problems you know? Climate change, mass migration, species extinction, soil degradation, rise of populism, mental health crisis, etc etc etc.

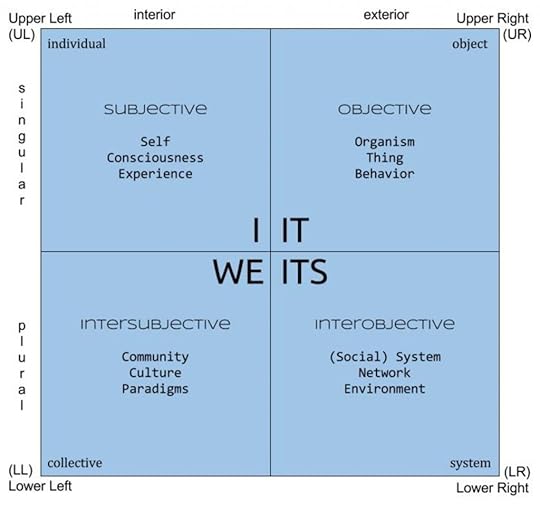

If you’re wondering what the authors mean by “multi-dimensional”, the fundamental idea is that all of the existence, all knowledge can be mapped into four basic quadrants underlying the Universe. This division is based on two parameters: internal and external, on the one side, and singular and plural on the other. Adding those up we arrive at four quadrants:

Upper Left (UL); subjective: individual, self, consciousness, experience – I

Lower Left (LL); intersubjective: collective, community, culture, worldviews – WE

Upper Right (UR); objective: object, organism, thing, behavior – IT

Lower Right (LR); interobjective: system, (social) structures, networks, environment – ITS

Just to make matters even more complicated, Watkins and Wilber observe that every problem needs to be viewed through a variety of lenses and tackled with corresponding solutions – these lenses being political, economic, social, technological, legal and environmental.

Your head might be exploding at this point – four quadrants, six lenses – does that mean looking at a problem 24 different ways before you even start solving it?!

Well, maybe, or maybe not. And the views that follow are my own, not those of W&W.

I take the above model to be a vital reminder that we cannot solve a wicked problem if we fail to recognise that it has multiple dimensions. By definition, a campaign simplifies a problem and presents a silver bullet solution. (Chris Rose, author of How To Win Campaigns: “Education, while good in itself, is a broadening exercise. It uses examples to reveal layers of complexity, leading to lower certainty but higher understanding. Don’t use it to campaign. Campaigning maximises motivation of an audience, not its knowledge. Use education to campaign, and you’ll end up exploring your issue but not changing it.”) So while the campaign may succeed, the resulting action may well fail.

For example, let’s say that Mr Trump sees the light on climate change (go on, dare to dream): he develops the political will and puts in place a legal framework to ensure environmental protection. But he hasn’t considered the impact on his grassroots supporters at the social level, or his business buddies at the economic level. And the technological solutions are there, but the green tech industry isn’t yet developed enough to make his legislation viable. So the policy fails, he loses his grassroots support, and gets voted out at the next election. (Do I hear cheering?)

Clearly a new style of leadership is going to be necessary. No matter how intelligent a leader may be (or not), it’s not possible for one person to be an expert in all of these realms. Collaborative leadership is going to be increasingly necessary. This may even look like no leadership at all.

Some interesting books I’ve read on this over the last few years:

Reinventing Organisations, by Frederic Laloux. From the back cover: “The way we manage organizations seems increasingly out of date. Deep inside, we sense that more is possible. We long for soulful workplaces, for authenticity, community, passion, and purpose. In this groundbreaking book, the author shows that every time, in the past, when humanity has shifted to a new stage of consciousness, it has achieved extraordinary breakthroughs in collaboration. A new shift in consciousness is currently underway. Could it help us invent a more soulful and purposeful way to run our businesses and nonprofits, schools and hospitals? (If you prefer video to reading, this is a long one but a good one.)

Danah Zohar

Danah ZoharRewiring the Corporate Brain, by Danah Zohar. From the back cover: “Corporate structures, like the physical and biological structure of the human brain, operate from one of three individually distinct but intricately interrelated systems: mental, emotional, and spiritual. The healthiest organizations, like the healthiest minds, learn to respond and adapt to external stimuli through a well integrated union of all three structures rather than a single, rigid approach. Business models, however, primarily neglect emotional and spiritual components in their operations, placing emphasis instead on efficiency, results, and other qualities readily associated with the mental structure alone. With only one-third of the corporate brain utilized, the remaining two-thirds present a vast reserve of ideas and opportunities for responding creatively to the daily demands of corporate life. Rewiring the Corporate Brain offers a new way to think about, lead, and structure organizations for fundamental transformation. It demonstrates how people must change the thinking behind their thinking – i.e., rewire the structures of the corporate brain – to operate more fully and achieve genuine fundamental organizational change. Written for managers at all levels, Rewiring the Corporate Brain takes its lead from quantum, chaos, and the latest brain sciences to offer practical, accessible, and inspiring alternatives to traditional structures in corporate design, practice, and implementation.” Memorable quote, attributed to a FTSE 100 CEO as he came into a management meeting (somewhat paraphrased): “It’s just as well we know we don’t know what we’re doing, because if we thought we did know what we’re doing, we’d probably f*** it up.”

Crowdocracy, by Alan Watkins. From the back cover: “Crowdocracy discusses one of the world’s most debated and critical issues – who decides our future and how should we be governed? Democracy is struggling to produce solutions to the challenges of our times. Populations feel disenfranchised with the political process, with the real power today being in the hands of a small elite. Crowdocracy offers a radical new way forward, one that allows all of us – not just some of us – to participate in how we are governed. Using technology and the insights of crowd wisdom, the authors describe how all of us can replace our elected officials and ultimately shape and govern our communities. A revolutionary idea that can be implemented in an evolutionary way.” Surprising fact: a group made up of “smart” and “not so smart” people consistently produces better results than a group made up of exclusively “smart” people.

With my Sisters hat on, I can’t help feeling that this has powerful implications for female/feminine leadership. The era of the lone wolf is over. It is the traditionally feminine skill of collaboration that is needed now – leadership will become an explicitly collective endeavour, rather than a vehicle for a single ego.

Of course, this also has important implications for followership. We can’t wait for a hero to come along and fix things. This is going to take all of us, bringing what we can, playing our part. This means we need to get informed, get engaged, get involved.

No more passengers. Only crew!

Next blog post: Should we be looking at problems? Or at solutions?

November 29, 2018

From Ego System to Eco System

Thanks to everybody who wrote to me after my last blog post , on Wildfire and Gunfire. It was interesting that it evoked such a positive reaction – these are evidently issues that trouble many of us, and we are in search of explanations and, ideally, solutions.

So I’ve been digging deeper. And have uncovered an interesting idea that would point to the same root cause underlying both the lack of environmental stewardship (wildfire) and the growing propensity to run amok with guns or knives (gunfire).

Philip Shepherd

Philip ShepherdI started reading Radical Wholeness: The Embodied Present and the Ordinary Grace of Being, by Philip Shepherd. Relevant to the wildfire issue and the environment more generally, he writes:

“When our thinking unmoors itself from the body . . . we come to feel and believe that we are superior to the world and distinct from it and that the fate of humanity is somehow sealed and independent from that of life on Earth.”

He sees this disconnect as being at the heart of patriarchy, which is not merely a gender issue, but more broadly a desire to dominate over, rather than partner with. (This chimes with The Chalice and the Blade, which I reviewed earlier this year.)

Shepherd points to the aspect of the western cultural story in which the brain has been idolised at the expense of the body, and how this loss of integration has trickled out into all of our institutions.

“The Story of Western culture asserts through those particulars a range of messages: that humans stand as independent of nature as our skyscrapers do; that the head should be in charge of the body, just as a CEO is in charge of a corporation; that we can own trees, land and animals; that self-mastery is the means to success; that what we feel as ‘the self’ lies within the boundary of the skin; that the pursuit of happiness is the primary goal of our lives; and that money buys security.”

If you’re thinking that all these ideas are self-evident, and so what anyway – well, that is how cultural stories work.

“Because the Story is largely invisible, its instructions rule us without our being aware of it. Nations, economies, scientists, religions and social movements are held in its sway. As the politics of our world amply demonstrate, what ‘feels right’ to voters is frequently contrary to their interests and immune to logic. The Story they have grown up with is their primary reality and they vote to perpetuate it…. The most difficult thing in the world is to question an assumption you’ve never consciously made—and the Story hides such assumptions in our language, our architecture, our customs, our institutions and our very neurology. How do you even begin to question something that is so normal it’s invisible?”

When we examine this cultural belief about the superiority of the brain, with the rest of the body existing primarily to provide nourishment, transportation, and the means by which the brain’s ideas get translated into reality, it fairly quickly falls apart. Sure, we don’t do so well if somebody cuts our head off, but we don’t do so well without a heart, or a gut, either. The body is an integrated system, and apart from the odd appendix or tonsil or even a limb, it’s all necessary to the healthy functioning of the whole.

In the same way, all members of society are necessary to the healthy functioning of the whole. Even though they may get paid a lot less (which is a whole other story), a company needs its workers, a community needs its nurses, teachers, and firefighters, and humans need nature (which gets paid nothing at all).

The problem comes when a society forgets that everything is connected and, as Mahatma Gandhi said, “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” So now we come to the gunfire. In the other book I’ve been reading this week, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, Sebastian Junger examines what has gone wrong with our western society, especially the way that it has made people feel disconnected, isolated, unwanted and unnecessary. He points out:

The problem comes when a society forgets that everything is connected and, as Mahatma Gandhi said, “A nation’s greatness is measured by how it treats its weakest members.” So now we come to the gunfire. In the other book I’ve been reading this week, Tribe: On Homecoming and Belonging, Sebastian Junger examines what has gone wrong with our western society, especially the way that it has made people feel disconnected, isolated, unwanted and unnecessary. He points out:

“A person living in a modern city or a suburb can, for the first time in history, go through an entire day—or an entire life—mostly encountering complete strangers. They can be surrounded by others and yet feel deeply, dangerously alone. The evidence that this is hard on us is overwhelming. Although happiness is notoriously subjective and difficult to measure, mental illness is not. Numerous cross-cultural studies have shown that modern society—despite its nearly miraculous advances in medicine, science, and technology—is afflicted with some of the highest rates of depression, schizophrenia, poor health, anxiety, and chronic loneliness in human history.”

Hr cites a global survey by the World Health Organization, which shows that people in wealthy countries suffer depression at as much as eight times the rate they do in poor countries, and people in countries with large income disparities—like the United States—run a much higher lifelong risk of developing severe mood disorders.

He concludes:

“The mechanism seems simple: poor people are forced to share their time and resources more than wealthy people are, and as a result they live in closer communities.”

Particularly poignant in the light of the Thousand Oaks shooting, committed by a veteran, is his observation that, in a modern western culture, often the only circumstance in which a person can experience true connection is in armed conflict.

“The earliest and most basic definition of community—of tribe—would be the group of people that you would both help feed and help defend… Soldiers experience this tribal way of thinking at war, but when they come home they realize that the tribe they were actually fighting for wasn’t their country, it was their unit. It makes absolutely no sense to make sacrifices for a group that, itself, isn’t willing to make sacrifices for you.”

Sebastian Junger

Sebastian JungerJunger makes some incisive observations on the current-day USA.

“Today’s veterans often come home to find that, although they’re willing to die for their country, they’re not sure how to live for it. It’s hard to know how to live for a country that regularly tears itself apart along every possible ethnic and demographic boundary. The income gap between rich and poor continues to widen, many people live in racially segregated communities, the elderly are mostly sequestered from public life, and rampage shootings happen so regularly that they only remain in the news cycle for a day or two. To make matters worse, politicians occasionally accuse rivals of deliberately trying to harm their own country—a charge so destructive to group unity that most past societies would probably have just punished it as a form of treason. It’s complete madness, and the veterans know this. In combat, soldiers all but ignore differences of race, religion, and politics within their platoon. It’s no wonder many of them get so depressed when they come home.”

Yet could it be that in the consequences of our disconnection, there might lie the cure?

As nature – and disenfranchised members of society – fight back, we have the opportunity to draw together as communities and even as a species – if we choose to. As conflicts increase, intensified by dwindling access to food and water in some parts of the world, migration will inevitably increase. At the moment it seems that the response of many countries to this increasing disruption is to pull up the drawbridge. But if we can seize this opportunity to rediscover our shared humanity, this era could be the transformative crucible that we need.

Drawing on evidence from the Blitz and other periods of extreme hardship, Junger posits that:

“As people come together to face an existential threat, class differences are temporarily erased, income disparities become irrelevant, race is overlooked, and individuals are assessed simply by what they are willing to do for the group. It is a kind of fleeting social utopia…. The beauty and the tragedy of the modern world is that it eliminates many situations that require people to demonstrate a commitment to the collective good. Protected by police and fire departments and relieved of most of the challenges of survival, an urban man might go through his entire life without having to come to the aid of someone in danger—or even give up his dinner.”

“It was better when it was really bad,” someone spray-painted on a wall about the loss of social solidarity in Bosnia after the war ended. That sense of solidarity is at the core of what it means to be human and undoubtedly helped deliver us to this extraordinary moment in our history. It may also be the only thing that allows us to survive it.

November 21, 2018

Wildfire and Gunfire

I’ve just returned from California, where I was combining a series of speaking engagements and spending time with friends, old and new.

It was an intense time to be in the US. No matter where you are in the world, you may well have heard about the wildfires that have been ravaging California, from one end of the state to the other. These are largely due to the prolonged drought in that part of the world, which has left huge areas as dry and volatile as tinderboxes, and has killed an estimated 102 million trees, just when we most need their contribution to carbon drawdown. The wildfires will have claimed many more. The human toll has been terrible, but so has the toll on an ecosystem already under pressure.

Then there have been the shootings. Last week I spoke in Thousand Oaks near Los Angeles, the night after a shooting in a bar less than 6 miles away took the lives of 12 people. (A couple of days later the town was evacuated because of wildfires. They were having a really terrible week.) This, in a place that earlier this year was designated the third safest city in the US. This was the 307th mass shooting (defined as more than 3 people dead, not including the shooter) in the US so far this year.

Also while in the US, I was on the East Coast during the mid-term elections, when a record number of women (but still not enough) were elected to Congress, increasing from 84 to 102 out of 435 members.

When I hear about headlines like this, I get curious. These visible events are just the tip of the iceberg, and the media often doesn’t dig deeper. So let’s look deeper now. I should emphasise that this is my blog, so these are my theories. Feel free to disagree and debate. I’m always interested in getting closer to the truth.

Events: wildfires

Events: wildfires

Trends: are these becoming more, or less, frequent? Definitely more. And more deadly. (See Time article: California’s Wildfires Have Become Bigger, Deadlier, and More Costly. Here’s Why.)

Causes: dead trees and dry grass due to prolonged drought. What causes the drought? Could it be climate change? How are we as humans creating, promoting, or allowing these conditions?

Underlying narrative: assumption that nature always has provided and always will provide for humans, no matter how many of us there are, or how much we compromise our ecosystems

Events: mass shootings

Trends: are these becoming more, or less, frequent? Definitely more. And more deadly. (And yes, I know those are the same words I used about wildfires. See article in the Washington Post: The Terrible Numbers That Grow With Each Mass Shooting.)

Trends: are these becoming more, or less, frequent? Definitely more. And more deadly. (And yes, I know those are the same words I used about wildfires. See article in the Washington Post: The Terrible Numbers That Grow With Each Mass Shooting.)

Causes: some theories are put forward in this article in Psychology Today: Mass Public Shootings Are On The Rise. I also think there is a gender issue here. According to Statista, less than 3% of mass shootings are committed by women. Negativity and isolation are reaching epidemic proportions in so-called “developed” societies, and speaking generally, in women this negativity is internalised in the form of depression, while in men, it is externalised as anger. If these issues are primarily expressed in developed societies, we have to ask ourselves just what it is that we are developing. Not widespread sanity and sound mental health, that’s for sure.

Underlying narrative: in a purported meritocracy, everybody is “entitled” to get what they want – money, success, fame, sex, whatever. And if they don’t get it, they get frustrated, then angry, then explosive.

(And I’m certainly not having a go at the US here. We in the UK have our own problems with the rise in stabbings. Same problem, different access to weapons.)

And now to something more cheerful….

Events: more women running for, and being elected to, office

Events: more women running for, and being elected to, office

(some very encouraging stats here, not just about the quantity, but also the quality, of female candidates)

Trends: not only more women, but also more gay, trans, indigenous, Muslim, and other minorities (CNN)

Causes: elected officials need to look more like the people they’re supposed to represent

Underlying narrative: “Well, heck, I can do better than THAT guy” / “If you want something done properly, do it yourself”

Clearly, we as a species could be doing things better. Some trends are heading in a positive direction, some not so much.

What vision should we be aiming for? I’d like to offer a book recommendation – a quick read, and for once, fiction. Herland, by Charlotte Perkins Gilman, published in 1915. It’s only 146 pages, but if even that is too long then check out the Sparknotes. The premise is that three male adventurers fly into an isolated country populated entirely by women, who have created a paradise of orderliness and good sense, where food production, reproduction, clothes, education, child-rearing and everything else are designed in an eminently sensible way.

We will never know if this would indeed be the case, and I doubt it would be fun to find out. But it’s an intriguing thought experiment.

P.S. In poignant juxtaposition to the destruction wrought by the fires, the book I was reading while in California just happened to be the most beautiful and fascinating tribute to trees that I have read: The Hidden Life of Trees, by a German forester called Peter Wohlleben. I highly recommend it. You will never look at a tree in quite the same way again.

October 18, 2018

Spaceship Earth

Once upon a time there was a great civilisation that wanted to explore the stars. They knew that this would be a very long journey, so they built a great spaceship that contained everything necessary to sustain life indefinitely, provided that the cosmonauts abided by the ship’s rules and shared their supplies fairly. The great day came, and they launched the spaceship into the sky.

Years passed. The spaceship forged on through the cosmos. The first generation of cosmonauts died off, and were replaced by their children.

More years passed. Generations came and went. Now there was nobody on board who remembered where they had come from, or even where they were going to. Their spaceship was the only home they had ever known.

The cosmonauts forgot who they were, and they forgot about the ship’s rules. Some of them wanted more than their share of the resources, and they started to fight the other cosmonauts so they could take their share. The other cosmonauts fought back.

Soon everybody was fighting everybody. They shot at each other and threw bombs at each other. They damaged and spoiled the very things they were fighting over. With all this fighting going on inside, the very fabric of the spaceship began to come apart.

That’s as far as the story goes. It hasn’t ended yet.

With thanks to Zach Ho who told a version of this story during SEEDS Leadership in Toronto a couple of months ago.

And thanks to Buckminster Fuller, who popularised the term Spaceship Earth. His original Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth (1969) is available here. There is a good summary/commentary by Balint Bakos here. And another one at Gaia.com here. Also many resources on the website of the Buckminster Fuller Institute. I strongly recommend finding out more about the work of this extraordinary visionary.

Other Stuff:

I leave next week for a trip to the US, where I’m speaking in the San Francisco area (for two corporate clients), Baltimore (National Aquarium), and Los Angeles (Outward Bound and the Ocean Institute). Do please come along to the public events if you’re in the area – I’d love to see you!

October 3, 2018

Musings on Spirituality

At a speaking engagement at Cumberland Lodge for Windsor Leadership recently, I was asked if I had a spiritual faith that helped sustain me in the middle of the ocean. Given that both my parents were Methodist preachers, some people wonder if I have followed in their footsteps and have a strong Christian belief system.

To which I would say – not really. I do have a strong sense of the spiritual, but it wouldn’t fit into any conventional world religion that I am aware of, although some form of Buddhism would probably be the closest.

Like any question of faith, I have no definite answers. Rather, I have a belief system that works well for me. I don’t claim it as factual truth. The corollary of this is that I am absolutely happy for anybody else to believe whatever they want to believe, so long as it doesn’t impinge on my freedom to believe what I want to believe.

My general thoughts on the subject go something like this:

– We know that reality as we experience it is not reality as it really is. Humans have evolved over the generations to favour the attributes conducive to survival, rather than the ability to perceive the “real” reality in all its dimensions. For example, it could well be that hyper-sensitivity to danger (fast movement, loud noises, etc) was genetically preferable to a more rounded view of the world, as the individual humans who spotted danger first were more likely to get the opportunity to pass on their genes.

– We know that reality as we experience it is not reality as it really is. Humans have evolved over the generations to favour the attributes conducive to survival, rather than the ability to perceive the “real” reality in all its dimensions. For example, it could well be that hyper-sensitivity to danger (fast movement, loud noises, etc) was genetically preferable to a more rounded view of the world, as the individual humans who spotted danger first were more likely to get the opportunity to pass on their genes.

– Given the above, plus the very inadequate nature of our paltry five senses, and our very short time perspective, there are probably many things that exist in reality of which we have no conscious awareness, because we have no sense organ to detect them, or they are too big or too small to comprehend, or they operate on a time scale that is imperceptible to us (e.g. tectonic plate shift).

– So it could be that things that we regard as “spiritual”, such as synchronicities, seemingly telepathic connections, ability to perceive things at impossible distances of time or space, etc are actually capable of scientific explanation, if only we were sophisticated enough and knew what we were looking for (although I can’t help feeling that a bit of the magic would be lost if we could scientifically explain these “spiritual” phenomena).

Further to all the above, I would like to think that it is possible that we are entering a “shift of consciousness” stage, where a tipping point will be reached and we as a species will suddenly see things in a different way. Maybe we will rediscover our connection to each other and to the other parts of nature, and stop behaving like we are all isolated individuals, competing with each other for wealth, resources and attention.

Further to all the above, I would like to think that it is possible that we are entering a “shift of consciousness” stage, where a tipping point will be reached and we as a species will suddenly see things in a different way. Maybe we will rediscover our connection to each other and to the other parts of nature, and stop behaving like we are all isolated individuals, competing with each other for wealth, resources and attention.

Maybe. And maybe not. Given the rapidity at which the train is approaching the ravine, with seemingly no bridge, no brakes, and no points to shift us onto a different track, let’s hope that this actually is happening, unlikely as it may appear from where we are now. (Ecomodernists take a more optimistic view, which you are welcome to try on for size by reading their manifesto. Thanks to Canon Bryan for bringing this to my attention.)

I know hope is NOT a strategy, but we are running out of options, and last-minute miracle might be our best bet, even while many of us continue to strive for sustainability.

Either way, I take comfort from the fact that this planet will long outlive humanity, and despite all the damage that we have inflicted on it, time is a great healer.