Roz Savage's Blog, page 17

November 14, 2019

What Equality Is Not

I never thought I’d say this, but I’m having real doubts about equality for women.

Before you recoil in horror (or possibly leap to agree), read on.

Yesterday I had a tremendously useful session with Marc Fest of Elevator Speech Training, who wrought miraculous improvements on my Sisters pitch in the space of a fast-paced hour. One of my action points was to research more data to back up my main points, including how much better corporations, countries, and families perform when women have a more active say.

All started well.

For corporations: “When Fortune-500 companies were ranked by the number of women directors on their boards, those in the highest quartile in 2009 reported a 42% greater return on sales and a 53% higher return on equity than the rest.” Women deal more effectively (less aggressively) with risk, they temper the over-confidence of male CEOs (HBR), tend to focus on long-term priorities (Warwick Business School), and offer less conformist perspectives. And the very obvious fact that, given that at least some of their customers will be female, having women in the boardroom helps companies relate in a more gender-balanced way.

For countries: “Women in government… advance population health… substantively advance women’s rights in areas such as pay equity, violence against women, health care and family policy… are also more effective at building coalitions and reaching consensus.” (WEF) “When women are in sufficient numbers in parliaments they also promote children’s rights and they tend to speak up more for the interests of communities, local communities, because of their close involvement in community life.” (UN conference in Chile)

For families: “When women work, they invest 90 percent of their income back into their families, compared with 35 percent for men.” (Clinton Global Initiative. No data was offered on what the guys spend their money on. :-/)

So far, so good.

But hold on a moment. What is this?

An excerpt from McKinsey’s October 2017 report: “Women Matter: Ten years of insights on gender diversity”. (Well, gosh, so nice to be told we matter.)

An excerpt from McKinsey’s October 2017 report: “Women Matter: Ten years of insights on gender diversity”. (Well, gosh, so nice to be told we matter.)

The phrases that particularly caught my attention (aka “made my jaw drop”) were on p12:

Title: An answer to the labor force and talent shortage Tagline: Gender diversity is a key battlefield for economic growth in aging countries and for companies to win the talent war

Women are actually one of the largest pools of untapped labor… The entry of more women into the labor force would be of significant benefit to countries with aging populations that face pressure on their labor pools and therefore, potentially, on their GDP growth.

At this point, I’m having to assume that McKinsey’s intended audience is NOT women, but rather stereotypical white, middle-aged (or older) males who still need convincing that women should have a seat at the boardroom table. So they are pitching equality as being, not for the benefit of women, but for the benefit of the CEO’s pension and healthcare needs.

These few lines strongly give the impression that large companies/capitalism need women far more than women need large companies/capitalism. Why would women voluntarily go into masculine structures that primarily reward masculine behaviours? We already know about the disproportionate toll it takes on our physical and mental health (and if you follow those links, you’ll see it’s not too great for the guys, either).

If we women are so smart, why wouldn’t we set up our own companies along gender-balanced lines, and be our own bosses, instead of devoting our time, talent and energy to further enriching the (98% male) 1%?

And don’t even start me on the “battlefield” and “war” imagery. So dominator, so non-partnership (to channel Riane Eisler).

I needed to share my general state of gobsmackery with a kindred spirit, so I sent the link to a friend in California, obviously knowing I’d be singing to the choir.

Her response: “I glanced through and the photos called my attention. All the women are young, fit and attractive. The men are mostly average looking. The main image sends the implicit message that women are just now coming onto the scene (witness the main photo with attractive older white male in power suit shaking hands with young woman wearing nondescript utilitarian masculine mode clothing. No question who has the power here. The other main image is a young eye shot from a come hither angle (above). The mom is harried (but gorgeous) and her kid is none too happy. The dad is average, relaxed, with happy child. Everyone wears conforming black shoes…but only one female out of four and her shoes are painfully high sexy stilettos. The imagery has an implicit power dynamic that’s palpable. I’d love to see a cover photo of EQUALS shaking hands.”

Amen, sister.

This report has really highlighted for me the bluntness of the aspiration of “equality”, and the need for greater refinement.

Should women receive equal pay for equal work as men? Yes, absolutely!

Should more of the traditional “women’s work” – caring for children, sick, elderly – be rewarded? Totally!

Do we want women to have equal access to healthcare, and for women’s medical issues to be given equal priority with men’s? Goes without saying.

But this report implies that women are seen as being huge pool of untapped labour – wanting to bring more women into organisations that are still structured in ways that are not beneficial for them, to prop up GDP growth (a very dubious measure of wellbeing) and an ageing population.

So we need to be careful – are women being brought into the workplace from a genuine appreciation of what they bring, or more to support the existing “yang” paradigm?

There are many different dimensions to equality. Some of them are desirable – and some are not. Too often in this report it feels like “equality” is assumed to mean that women’s economic participation should look the same as men’s, i.e. we conform to the masculine standard.

What we actually need is more of the feminine – no matter whether that is embodied by a man or a woman.

P.S. And while I’m on the subject, check out yesterday’s article by Umair Haque: (Why) the Future is Feminine.

November 6, 2019

We Need A New Narrative

I’m now back from my mega month-long US trip, and getting my feet back under my desk. The next few months will be spent in very hermit-like fashion, focusing on my doctorate. But still blogging on a weekly basis – I really appreciate these opportunities to share my thoughts and get feedback.

I’ve mentioned George Monbiot’s excellent 2019 TED Talk before (in a blog post in August), and make no apology for mentioning it again – especially as I have just got off the phone with George, who was rather busy given his involvement with Extinction Rebellion, and XR had just won their High Court case, but was still good enough to make time for our call.

(And so great to see the very impressive Bella Lack right there on the XR home page.)

In his highly entertaining talk, George says we need a new story to replace the old neoliberal story of individualism and selfishness, which passed its use-by date with the financial crash of 2008 (if not earlier) but has yet to be replaced with a compelling new story.

Yes, we need a new story that we can rally around. The narrative we currently believe in would appear to be one of dominion over the Earth, rather than stewardship, or even partnership. Possibly this is based on a mistranslation of the Genesis story, which we usually hear thus: “And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness: and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air”. But see this site for a less anthropocentric interpretation. Certainly, the “dominion over” version isn’t working out so well for us at the moment, and “partnership with” would seem to be an excellent idea.

George reports on recent findings from sociology, psychology and neuroscience, which tell us that human beings are wired for altruism, compassion, and cooperation. After all, we’re not the strongest, fastest, or biggest creatures, so we had to have something going for us to achieve our runaway success. And I believe that we ARE altruistic. I have often been on the receiving end of a great deal of generosity and altruism, and hopefully also on the giving end.

And yet we live in structures and systems that tell us otherwise. The media over-emphasise the oligarchs and CEOs and politicians who are only out for themselves, for money and power, living in a zero-sum game where greed is good, and you are either a winner or a loser. And so we end up in a race to the bottom of a dog-eat-dog world.

Alex Evans, in his book The Myth Gap, tells us that we need to embrace a myth of “a bigger us, a longer now, a different kind of good life”. George suggests that this could start by embracing the commons as a starting point, in a participatory democracy, a politics of belonging. (See Nobel Prize Winner Elinor Ostrom on the governance of the commons.)

So how do we change the system, when the world is run by people who have benefited from the status quo? We start from the grassroots. And this – I believe – is where women and girls REALLY have to step up and make our voices heard.

George and I agreed that some of the most powerful voices emerging right now are women: Greta Thunberg, AOC, Kate Raworth, Ellen MacArthur. As well the other wise women who have been great influences for a decade or more – Barbara Marx Hubbard, Riane Eisler (who I saw last month at her home in Carmel), Polly Higgins (see my tribute to Polly earlier this year).

It’s happening. Economic, social, political and environmental change is coming, in a big tidal wave.

I’m sure I’ve quoted this before, and I’m going to quote it again, as it’s a rare day that I don’t mentally refer to it.

And by the way, it’s a pretty good narrative to live by.

“You have been telling people that this is the eleventh hour.

Now you must go back and tell people that this is the hour!

And there are things to be considered:

Where are you living?

What are you doing?

What are your relationships?

Are you in right relation?

Where is your water?

Know your Garden.

It is time to speak your truth.

Create your community.

Be good to yourself.

And not look outside of yourself for a leader.

This could be a good time!

There is a river flowing very fast.

It is so great and fast that there are those who will be afraid.

They will hold on to the shore.

They will feel that they are being torn apart, and they will suffer greatly.

Know that the river has its destination.

The elders say that we must let go of the shore,

push off into the middle of the river,

keep our eyes open,

and our heads above the water.

See who is in there with you and celebrate.

At this time we are to take nothing personally,

least of all, ourselves.

For the moment that we do,

our spiritual growth comes to a halt.

The time of the lone wolf is over.

Gather yourselves!

Banish the word struggle from your attitude and your vocabulary.

All that we do now must be done in a sacred manner and in celebration.

We are the ones that we have been waiting for.”

– The Elders, Oraibi, Arizona Hopi Nation

[Featured image: Top row, L-R Bella Lack, Kate Raworth, Polly Higgins. Bottom row, L-R Greta Thunberg, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Riane Eisler.]

October 31, 2019

Leading the Way into Liminality

This is something I drafted for my DProf, which I probably won’t use, but for the purposes of my blog it seemed a good way to round out what I’ve been sharing over the last month or so about the liminal space. This is what I’ve been trying to do, over the last 16 years, to boost my own courage around entering the unknown, and hoping to inspire others to likewise muster their courage and metaphorically row into unknown waters.

I first entered the liminal space in 2002, when I left the safe bubble of my married, mortgaged existence and leaped into the unknown. It had been a terrifying prospect, as just about everybody I knew was living inside identical bubbles, and I had genuinely no idea what lay outside. However, in true Hero’s Journey style, my boldness was rewarded and mentors and allies soon showed up.

By the time I received my call to adventure, in 2004, I had learned to feel secure with insecurity, and was a total convert to the freedom of living outside the gilded cage of cultural conventionality. In drawing attention to myself through rowing oceans, as well as promoting my environmental message, I hoped to model this different way of living as a possibility for people who possibly felt constrained by the old paradigm, as I had, but didn’t see other viable options either among their peers or in the media.

I know for sure of at least a dozen who have followed my lead into the liminal space, and trust that there may be many more of which I am not aware.

At the same time, I have become aware that there are many people who are living as what Daniel Quinn would describe as “leavers”, rather than “takers”, meaning that they have left behind the conventional culture to experiment with ways of living more harmoniously with each other and with the environment. For a long while it seemed that, when they left society, they all but disappeared. They were not profiled in the media, which continued to disproportionately feature the affluent and materialistic. Hello! magazine is not too interested in capturing exclusive photographs of somebody’s eco-home and low-impact lifestyle.

In the last few years, more of these stories are now being told, with books such as The Moneyless Man, by Mark Boyle, the book and film by Low Impact Man, Colin Beavan, and the individuals featured in Happier People Healthier Planet, by Teresa Belton. There are also countless books about people stepping into liminal spaces spiritually, in search of greater purpose and fulfilment.

In one sense, it is good news that these stories are being told. In another sense, it could be seen as not such good news that these stories are still deemed sufficiently exotic to be worthy of a book deal. The needle still has a long way to move before these lifestyles are regarded as normal.

It has been important for me, in telling my story, to emphasise my own normality, and my vulnerability. I have taken pains to emphasise that my background was very conventional, that I had the option available to stay resident in the status quo, that I had to make deliberate choices, and that I found the choices scary. In doing so, I have tried to convey that it is fine and understandable to feel apprehensive, but that the risks of stepping into the liminal space are likely to be worthwhile.

In reality, we are all in a liminal space, whether or not we know it. As we move further into the anthropocene, in which man’s mark on the world is increasingly evident, we are in a time of transition of our own making. The rate of change has never been as fast as it is now. We wonder if it can continue at this pace, or if the exponential line of our progress will crest and collapse like an ocean wave. It cannot hurt to have our wits about us, our eyes open. No matter where we’re headed, it’s better not to sleepwalk there. That is one powerfully good thing to be said about the liminal places: nothing promotes alertness like venturing into the dark cave.

In reality, we are all in a liminal space, whether or not we know it. As we move further into the anthropocene, in which man’s mark on the world is increasingly evident, we are in a time of transition of our own making. The rate of change has never been as fast as it is now. We wonder if it can continue at this pace, or if the exponential line of our progress will crest and collapse like an ocean wave. It cannot hurt to have our wits about us, our eyes open. No matter where we’re headed, it’s better not to sleepwalk there. That is one powerfully good thing to be said about the liminal places: nothing promotes alertness like venturing into the dark cave.

Maybe it’s fitting that this blog post comes out on Halloween, which before it was about costumes and candy was about warding off ghosts. What are the terrors that we are trying to ward off now?

Happy Halloween! (a phrase which has always seemed rather oxymoronic to me)

October 24, 2019

No Action = Action

I’m taking a break from the doctoral musings to share some thoughts that arose from this post in the ever-illuminating Brainpickings blog. This post shares sections from Martin Luther King’s Letter From Birmingham City Jail, and it particularly struck me how relevant his words, although written in the context of the civil rights movement, are to climate change and any other crime against nature.

Responding to a group of eight Alabama clergymen who had basically told him to take himself and his nonviolent protests elsewhere, accusing him of being an “outsider”, Dr King wrote:

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.”

Likewise, while we in the global north may feel relatively immune from the ravages of climate change – looking around the green English countryside around my home, it is hard to feel the immediacy and urgency of the crisis – it is clear that not one single inhabitant of Planet Earth, no matter where they live or what species they are, is going to be safe from the impacts of a warming climate.

He goes on to say:

“History is the long and tragic story of the fact that privileged groups seldom give up their privileges voluntarily. Individuals may see the moral light and give up their unjust posture; but … groups are more immoral than individuals. We know through painful experience that freedom is never voluntarily given by the oppressor; it must be demanded by the oppressed.”

Nailed it, Dr King. I’m sure that no individual who works in the fossil fuel industry, say, would say that they are willing to trash the future prospects of a liveable climate, and yet we now know that this is an inevitable consequence of their collective activities.

And yes, barring a few inspiring examples, those in power are rarely willing to surrender power in favour of justice and equality. See: slavery, conquistadors, women’s suffrage, civil rights movement, corporate ecocide, indigenous rights, the 1%, #metoo, etc etc etc.

Then comes the passage that really made me pause and go, “whoah”, and see the parallel with environmental destruction:

“All this … grows out of a tragic misconception of time that will inevitably cure all ills. Actually time is neutral. It can be used either destructively or constructively. I am coming to feel that the people of ill will have used time much more effectively than the people of good will. We will have to repent in this generation not merely for the vitriolic words and actions of the bad people, but for the appalling silence of the good people. We must come to see that human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability. It comes through the tireless efforts and persistent work of men willing to be co-workers with God, and without this hard work time itself becomes an ally of the forces of social stagnation. We must use time creatively, and forever realize that the time is always ripe to do right.”

“Human progress never rolls in on wheels of inevitability.” Within currently living memory, at least in the western democratic world, things have always got better. We have internalised a narrative that assumes that each generation will earn more than the previous one, be better fed, be healthier, be happier. That narrative is now running into a harsher reality. In the US, the UK, and many other parts of Europe, this next generation will struggle to find work, or buy their first home, will be more likely to be obese, die younger, suffer mental health issues. They will face a world of climate disruption that creates drought and food shortages, increases migration, destabilises already volatile regions of the globe.

Why? Because those who benefit from the status quo have been happy to let time drift on, at least until it’s not their problem any more. Kick the can down the road and let someone else deal with it. Keep the music playing in the global game of musical chairs, in the hope that the poor and the weak and the disempowered will collapse of exhaustion while we still circle the line of chairs, leaving the fat cats to claim the comfortable seats of power when the music does stop.

This brings me back to a sense I’ve had for a while, that nothing less than a shift to a higher level of consciousness will “fix” the climate. We can tinker with the problem by taxing carbon, reducing emissions, attempting to geoengineer our way out of trouble, but if we are still at the level of thinking that created the problem, once we’ve done the fixing, our flawed thinking will simply manifest in some other way. We will find something else to damage and destroy.

While we still live in a dominator society, in which it’s okay to look out for one’s own self-interest while failing to see that everything is connected in our “inescapable network of mutuality”, nobody is safe until everybody is safe. Our imperative now is to shift to a partnership society, governed by compassion, justice and equality. Not taking action is the most dangerous kind of action.

Can we do it? Is it possible for humans, flawed as we are, to make this leap of consciousness? I don’t know. But I know for sure that the only way to find out is to try.

October 17, 2019

The Rise and Fall of the Human Empire

Continuing my sharing of musings on liminality (aka the “threshold” places and times) from my doctorate. Having pondered liminality from the perspective of the individual, I’m moving on to think about entire societies entering a liminal, or transformational, phase – sort of in the hope that the world is entering one right now. Liminal spaces are never comfortable, but sometimes they are necessary. [The bits in square brackets are not in the draft of my thesis – they are just my flippant remarks to liven up a blog post.]

There are various analyses of the rise and fall of empires, but here I will focus on the 1976 essay, The Fate of Empires, by [the magnificently named] General Sir John Glubb. Glubb examined the life cycles of eight empires since 859 B.C., and concluded that each empire (Assyria, Persia, Greece, Rome, Arab, Marmeluke, Ottoman, Spain, Romanov Russia, and Britain) spanned around 250 years, or 10 generations, and passed through the following phases:

The Age of Pioneers: expansion of territory

The Age of Conquests: more expansion, not always peaceably

The Age of Commerce: wealth is created through trade and innovation

The Age of Affluence: all appears to be well, but the seeds of destruction are being sown

The Age of Intellect: the acquired affluence enables people to pursue the life of the mind. Academic institutions may produce sceptical intellectuals who start to question the dominant narratives of the empire, undermining its authority

The Age of Decadence: people indulge in excessive consumption in the pursuit of happiness, while in actuality becoming less happy. The civilisation creates diversions for the populace, from gladiator fights to Facebook and Instagram, while people indulge in addiction and debauchery. The values and discipline that enabled the creation of the empire are eroded

The Age of Decline and Collapse: inequality grows, increasing numbers are excluded from meaningful work and the means to fulfil their potential. Discontent leads to disruption and the empire collapses.

Glubb points to the heroes of an empire as a key indicator of where it is in this life cycle. During the early phases, pioneers and warriors are lauded. Then come the entrepreneurs and merchants. Once celebrities such as film stars, musicians, and athletes become the main focus of popular attention, no matter how flawed their characters, the empire is in trouble. Clearly this is where many countries in the western world are now. [See my blog post on Kardashians.]

The British historian Arnold Toynbee, in his 12-volume A Study of History, argued that the collapse of civilizations is not caused either by losing control over the environment, or attacks from outside. He posits that societies that develop great expertise in problem solving develop strong structures for problem resolution that they try to apply to all problems. So when new problems arise, requiring new structures, the methodology fails. [To the person who has only a hammer, everything looks like a nail. Except that not everything is a nail.]

He also argues that, during a period of social decay, some people are able to respond by transcending the current reality, meeting the challenges of the decaying civilization with new insights. They are then well positioned to create new structures and schools of thought better suited to the new reality, around which a subsequent civilization may begin to form after the old one has passed away.

This harks back to Donella Meadows’s number one leverage point for transformation of a system: the ability to transcend the existing paradigm. Whether that transcendence happens proactively in order to change the system, or reactively in response to the decline of the old system, is open to debate. Picking up on the wave metaphor of societal transformation mentioned elsewhere, it may make little practical difference: it may be the timing of the new paradigm, rather than its rightness, that is most likely to determine its success. In Darwinian terms, the “fitness” of an idea may be determined more by its fitness for purpose at the time it arises, rather than its inherent strength.

The German philosopher Karl Jaspers, in Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (The Origin and Goal of History), published in 1949, called this relatively fluid period of disruption an “axial age”, which he described as “an interregnum between two ages of great empire, a pause for liberty, a deep breath bringing the most lucid consciousness”. Bjorn Thomasson suggests that the Axial Age was a historically liminal period, when old certainties had lost their validity and new ones were still not ready.

These interstitial periods represent powerful transformational potential. Apparent chaos is an opportunity [to quote Petyr Baelish in Game of Thrones] for new ideas and structures to take hold and become established. I have for several years felt intuitively that there needs to be a strategy covering the most important aspects of human society such as food, water, transport, energy, education, economics, and so on, using the best knowledge that we have at our disposal to forge a better future as the old structures break down. In a perfect world, there would be a smooth transition; new structures would be put in place that are so obviously more fit for purpose than the old structures that people would make the transition voluntarily. However, history suggests that this is unlikely, given the human tendency to cling to the old and familiar rather than courageously embracing the new. While humans have an appetite for novelty in terms of acquiring new things, few wish to leap into the radical newness of the liminal void, even individually, let alone collectively.

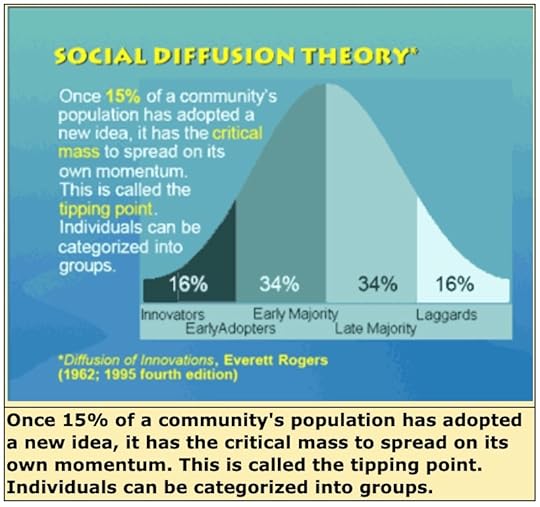

So how do we coax humanity into entering the liminal space, into the place where we can collectively re-imagine the way we inhabit this Earth? The good news is that we don’t have to have 100% of people thinking along these lines. We don’t even need 50%. According to Social Diffusion Theory, in the bell curve of adoption, from the innovators through the early adopters, the majority, and eventually the laggards, the tipping point lies somewhere between 15% and 20%.

So how do we coax humanity into entering the liminal space, into the place where we can collectively re-imagine the way we inhabit this Earth? The good news is that we don’t have to have 100% of people thinking along these lines. We don’t even need 50%. According to Social Diffusion Theory, in the bell curve of adoption, from the innovators through the early adopters, the majority, and eventually the laggards, the tipping point lies somewhere between 15% and 20%.

So even if you feel that kindred spirits are few, take heart. If you only encounter one person in five or six who has the courage to envision a better future, we’re on track. If you encounter fewer, see what you can do to tip them. If you encounter more, see how you can help them become more courageous advocates. Every conversation counts.

October 10, 2019

Living at the Edge

For the last couple of weeks I’ve been sharing chunks from the (very) draft version of my doctoral dissertation, and I’m continuing that this week with some more reflections on liminality, that slightly mysterious and transitional/transformational realm on the edges of society. Although transformation CAN take place en masse (and let’s hope for the sake of the world that it does, and soon!), historically it has been a solo enterprise, undertaken alone, and usually in nature. Here I explore some of the academic literature on the liminal state, and reflect on how it relates to my experiences on the ocean.

Historically, and still in some indigenous cultures, solitude is seen as sacred, a liminal space in which there is space for a re-creation of the self as it transitions from one chapter of life to the next.

“…the initiands live outside their normal environment and are brought to question their self and the existing social order through a series of rituals that often involve acts of pain: the initiands come to feel nameless, spatio-temporally dislocated and socially unstructured… the formative experiences during liminality will prepare the initiand (and his/her cohort) to occupy a new social role or status, made public during the reintegration rituals” ” (Bjørn Thomassen, “Liminality” in The Encyclopedia of Social Theory (London 2006) p. 322).

The folklorist Arnold Van Gennep (Rites of Passage, 1909) was the first to analyse liminality in an academic context. He identified three stages:

Preliminal rites (or rites of separation): In order to make space for the new, the initiate leaves behind her/his previous identity and ways of being.

Liminal rites (or transition rites): Traditionally, these follow a ritualised sequence, presided over by an officiant of some sort. The identity of the initiand is transformed as she/he passes over the threshold from one phase into the next.

Postliminal rites (or rites of incorporation): The initiand integrates the rite of passage to form a new identity, and is re-admitted to the community in this transfigured form.

Lacking only the officiant to supervise the transition rites, unless we hand that role to the ocean, this tracks exactly to my experience on the ocean, particularly my Atlantic crossing. There was a powerful sense of process in venturing away from dry land and into the liminal space of the ocean, having my old identity stripped away as many of the things that I would once have deemed essential (comfort, company, entertainment, communication) were shown to be optional luxuries, at the same time as an intense learning curve took me onto a higher plane of self-knowledge, wisdom, and understanding, and finally the process of returning to land and diligently doing the work of integrating the lessons learned on the ocean into the fabric of who I am in everyday life. Of lesser importance to me, but nonetheless following Van Gennep’s structure, was the societal recognition of my achievement as having been transformative, by the elevation of my social standing, invitations to write and speak, and awards such as the MBE, honorary doctorate, and so on.

(For a blog post from the Atlantic that reveal how this process felt at the time, see Day 49.)

Victor Turner picked up on Van Gennep’s work in the 1960s, and expanded its relevance beyond tribal societies. According to Turner, the liminal person’s sense of identity dissolves, as I described above in my own personal experience, creating a degree of disorientation that leads to the possibility of new perspectives. Turner suggests that liminality can be regarded as a period of withdrawal from normal cultural modes of social action, and is thus an opportunity to re-evaluate the central values and norms of one’s culture.

This certainly felt true in my case. In Stop Drifting Start Rowing I wrote of my return to dry land after rowing from San Francisco to Hawaii:

“As Mum and I were given a lift from the Yacht Club to my weatherman’s house, I went into reverse culture shock. The speed of the car seemed unnaturally fast. The skyscrapers of Waikiki seemed dangerously high. And all these people! I felt like a space alien seeing human civilization for the first time. I looked at the shops selling designer clothes, jewelry and electronics. I was quite perplexed that people would spend so much money on such pointless things. If you couldn’t eat it, drink it, or row with it, then what purpose did it serve? A rower’s needs are very simple – enough food and water, and a few miles in the right direction are enough to make it a good day. Examining my visceral reaction to the blatantly conspicuous consumption all around me, I realized that, having been so very materialistic in my early adult life, my values had fundamentally changed. Not only was I not interested in owning much stuff, I was actually repulsed by this flagrant consumerism.”

It did feel very much that I had been in what I now understand to be a “liminal space” and had come back with a fresh eye, able to see the prevailing culture through a more objective lens. This relates back to the idea of the operational narratives of a society: while we are living inside the narrative, we can no more see it than a fish can see the water. It is only when we separate ourselves from the society that we can see it clearly.

This contributed to the profound effect that Daniel Quinn’s Ishmael had on me. By casting a telepathic gorilla as the teacher, Quinn shifts the perspective from the human to that of an intelligent observer who can clearly see from one step removed the destructive path that humanity is pursuing.

How do we enable more people to achieve this degree of objectivity? It is said that travel broadens the mind, but that is increasingly untrue. Even though they may travel overseas and move through other cultures, most tourists and travelers are encased in a bubble of their own culture, insulated from exposure to a different narrative. Traveling in groups, or staying in hotels and hostels amongst people of similar nationalities, income brackets, and cultures, does not expand the mind in the same way as would, say, spending a month living with locals. So the artifice of their own cultural narrative is not revealed as it would be to the solo traveler.

There may be, to some extent, a fear of venturing into a liminal space, even those that are far less intimidating than the ocean or a foreign country. The disorientation mentioned above is an uncomfortable sensation for many. In tribal and some religious societies, where rites of passage involving liminality are undertaken by all (or at least, all males) on reaching a certain age, peer pressure, and the knowledge that one’s elders have all endured the experience, effectively render it non-optional. In non-tribal, secular societies, however, where social pressure to undergo a rite of passage does not exist, many people prefer to take the option of ease and comfort rather than challenge and transformation. There have been a few calls for the reinstatement of national service to provide a structured, disciplined transition into adulthood, which could be effective, but this remains a minority view.

What are your thoughts? Are you comfortable with discomfort, all cool with life on the edge? Or do you find it intimidating, and if so, what is it that scares you about it? Either way, I’d love to hear from you!

October 3, 2019

When Everything Suddenly Falls Apart

Following on from last week’s extract from my doctoral jottings, When Everything Suddenly Comes Together, this week we move on to when everything suddenly falls apart, as it did for me and my boat on the Atlantic voyage. If I had been more Buddhist at the time, I would have known that this is how it goes in the cycles of life. Things come together. Things fall apart. But at the time, I was just pissed off. But, as Steven Wright says, “Experience is something you don’t get until just after you needed it.”

Roz Savage rowing across the Pacific from San Francisco to Honolulu

Roz Savage rowing across the Pacific from San Francisco to HonoluluIf I had hoped to find enlightenment on the ocean, it turned out to be very different from what I expected. My role models had embraced a fairly contemplative path. There is not much that is contemplative about ocean rowing. It is a much more intense and distracting activity than sitting in a cave or a cabin. Equipment broke, waves tossed, winds blew (often not in the “right” direction), injuries and sores afflicted, and so on. My emotions veered between boredom and terror, with not that much in between. Serenity and insight seemed extremely distant, almost all of the time. As it was occurring, the experience seemed anything but spiritual. As environmental advocacy had been my prime motivating factor in venturing onto the ocean, I spent a lot of time feeling indignant that Mother Ocean was not showing more gratitude for my endeavours.

However, with the passage of time, I have come to discover the perfection in everything that went wrong. If everything had gone perfectly smoothly and according to plan, I would not have learned anywhere near as much as I did, conquered my fears and my inner demons (mostly), and grown as much as a person. It took a hostile environment like the ocean (hostile to humans, anyway) to humble me, strip away my ego, at times even make me just about forget who I was, other than a puny rower struggling her way across a vast ocean.

It seems particularly significant that both my onboard stereo and my satellite phone broke. I was able to use my stereo hardly at all: for the first month there was not enough sunshine to solar-power anything apart from the essentials, such as the watermaker, GPS, and satellite phone. Shortly after the sun came out, the stereo fizzled out due to corrosion, leaving me alone with my thoughts for the remainder of the journey. I was thus involuntarily subjected to the intense contemplative experience that I had wished for, with no opportunity for solace or distraction.

Julia Cameron

Julia CameronThere is a huge qualitative difference between occasional dips into distraction-free solitude, and an intense, nonstop, 103-day immersion. In the absence of external input, the mind reaches back into itself and brings up all varieties of thoughts, memories, and emotions. It is as if there is a membrane between the self and the outer world, and in our 21st century modern world the nonstop bombardment of words, music, advertisements, media, images, and other stimuli fills the channels of the membrane with inward-bound information. It is only when the external stimuli are suspended that the quieter, more subtle forms of information that lie within have the opportunity to emerge into consciousness. (The influential book on creativity, The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron, recommends a media-free Week 4 during the 12-week programme, which many participants find difficult and rewarding in equal measure. The reward side of the equation is the emergence of latent creative vision.)

This contemplative experience intensified after my satellite phone also succumbed to corrosion, leaving me incommunicado for the last 24 days of the voyage. It was only at that point that I realised what an intrusive portal, or umbilical cord, the phone was. Its demise made a massive difference to my sense of solitude; the contrast between lots of input and little input is nowhere near as great as the contrast between a little input and no input at all. My solitude was now complete.

One of the interesting features of my solitude was the erosion of my ego-based identity. In everyday life, we are usually unconsciously playing roles appropriate to our context, revealing different aspects of ourselves depending on whether we are with colleagues, with our boss, with friends, with parents, with children, or with our spouse or partner. Sometimes we are only aware of this when we feel a conflict between our roles, when worlds collide and we feel confused by the attempt to play two roles at once.

Alone on the ocean, there was no need to play any role at all. Especially after the satellite phone broke, releasing me even from the self-imposed obligation to write a blog post every day, I was in relationship with nobody and nothing apart from myself and my surroundings. On some levels this was liberating, to be so free to be and do whatever I wanted. I peeled back the layers of my identity, letting go of identification with my gender, nationality, race, education, profession, and so on. I wondered what I would find at my core: who or what was I when all else was stripped away? My (possibly disappointing) answer is that I found nothing. When all the layers had been discarded, there was nothing that I could point at and say with certainty, “that is me”.

Some may choose to see that as support of the hypothesis put forward by Bruce Hood, in The Self Illusion: Why There is No ‘You’ Inside Your Head, that the “self” does not exist as anything more than an assembly of experiences, opinions, responses, and internal storylines about “who I am”, generated by the brain to enable us to function in relation to the outside world.

My choice would be to interpret my personal experience (while recognising the paradox in this, and realising I may equally be in the grip of the “self illusion”) as supporting Neale Donald Walsch’s (God’s) revelation that we are all fragments of a unified consciousness, manifested into myriad forms in order to experience existence from as many different perspectives as possible. Possibly both these perspectives, despite coming at it from the seemingly opposing directions of science and spirituality, boil down to the same thing; what Aldous Huxley called “self-naughting”, or the mystic’s highest ambition to dissolve the self into union with the divine.

Abraham Maslow recognised something similar, adding a further level to his hierarchy above self-actualisation, to represent “transcendence”, i.e. giving oneself to something beyond oneself. He equated this with the desire to access the infinite. “Transcendence refers to the very highest and most inclusive or holistic levels of human consciousness, behaving and relating, as ends rather than means, to oneself, to significant others, to human beings in general, to other species, to nature, and to the cosmos.”

We don’t seem to talk about these ideas very much in everyday life, at least, not outside the walls of a monastery or convent. But isn’t it sort of important? Doesn’t it somehow relate to those questions like, “why are we here?” and “what’s the point?”. Even if you don’t think that transcendence, or anything like it, is the point, I think it’s something worth talking about. At some level, I believe we DO all have our own version of the reason why we’re here, even if we have concluded that there is no reason at all. Is it delusional to think that we do have some role to play, tiny, fleeting, and insignificant as we may be? Is it just an attempt by the ego to find some relevance for itself?

I don’t have any answers, but it’s fun to wonder.

September 26, 2019

When Everything Suddenly Comes Together

Today I’m sharing another draft section from my doctoral studies. The Doctorate in Professional Studies by Public Works is all about the candidate critiquing their own contributions and deriving further learning from the knowledge outcomes they have published in the public domain. In my case, those “publications” include my voyages, as well as the more conventional publications such as books, blogs, and speeches.

This section is about that wonderful feeling that you get when you have an idea for a project (or, more accurately in my case, the idea had me) that seems to bring together all the threads of your life into one glorious tapestry, as if all those experiences had been preparing you for this. Maybe even ventures that seemed like dead ends at the time suddenly become relevant again. In my worldview, that’s a clue that the new idea, however crazy it may seem, is exactly what I’m meant to be doing.

This is the first of four or five related sections that I’ve drafted, that I’ll share over the coming weeks. I’ll be on the road for much of October, so if you comment on my blog or reply to my newsletter, please forgive if it takes me even longer than usual to get back to you. I won’t be living in my inbox!

My ocean rowing voyages were, in effect, my first public works. When I received the call to adventure I knew only that rowing solo across oceans ticked all the boxes I had in mind, and sensed that all the experiences in my life had been leading up to this point. These two factors contributed to the sense that these adventures were in some way ordained by a higher power, or were “meant to be”. I little knew just how perfectly my voyages would embody the themes that were current in my life at the time, even when that perfection was heavily disguised in countless apparent imperfections such as injury, breakage, and loss.

Those themes that had been emerging in the lead-up to the call to adventure were:

– In Peru I had particularly enjoyed the physicality of trekking and climbing in the Andes, so a physical adventure of some sort appealed to me.

– I’d raced in a couple of marathons over the previous few years, drawn to the event by people telling me that I would find out things about myself in the last few miles of a marathon. This had been my motivation – the possibility of greater self-knowledge – but the marathon failed to enlighten. Maybe 26.2 miles just wasn’t far enough, and I needed a longer physical challenge, or even an adventure, but I didn’t seem qualified to do much. I didn’t know how to climb, sail, or cope with Arctic conditions. But I did know how to row.

– Although my book on my Peruvian adventure had not (and still has not) been published, I had very much enjoyed the experience of writing, while also appreciating the degree of detachment it gave me while traveling: even when plans were going awry, the inconvenience was outweighed by the prospect of rich material for my book.

– The environmental research I had undertaken in Ireland was still fresh in my mind. I wanted to see more of this planet before we degraded it even further. But I did not want my travels to hasten those changes, so whatever means of transport I chose would have to be environmentally friendly.

– I was desperate to raise awareness of our environmental issues. I needed a platform for my message, a way to get people’s attention. Rowing solo across oceans seemed sufficiently audacious and unusual to capture the public imagination.

– I was increasingly enjoying my own company, and the sense of self-reliance it engendered. I was growing as a person, discovering abilities and strengths that I hadn’t known I possessed, and I suspected there were more. But being rather lazy by nature I knew I had to put myself in a situation where I would have to fend for myself and not depend on someone else for assistance. I also wanted to find out who I was when I was alone – when I was not reacting to the expectations of others. Who was I when I was not being someone’s wife, girlfriend, daughter, sister, colleague, friend? So my new project had to be solo.

– I had recently read several books that emphasised the solitary inner journey, particularly surrounded by nature, as a pathway to spiritual growth: Tenzin Palmo’s Cave in the Snow, and Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. After my strides into individuation came a desire for initiation, a transformative rite of passage that would lead me into greater maturity and insight.

– I wanted to contribute to the greater good. It may have been partly due to the influence of my parents, who spent their lives in dutiful service to others, but I felt a strong need to leave a legacy. I knew I was unlikely to have children, so I wanted to find some other way to make my mark. I needed to believe that my time on this earth would leave the world a slightly better place than it had been when I arrived.

– Conversations with God had instilled in me a belief that my personal longevity was less important than my contribution to the collective consciousness, and to maximise this contribution I was no longer going to play small. It was time for me to step up, be bold, and make a statement to the world about who I was in this new identity.

There was also a newfound awareness of the importance of liminal spaces, the “fertile void of uncertainty”, to use Deepak Chopra’s phrase, where enculturation and social norms melt away into the background, and the individual is relatively free to define their own reality from within, rather than having it imposed from without. Oceans seemed, quite literally, a fluid realm where I would be free to explore and re-create my self and my reality.

It did, indeed, feel as if everything in my life had been leading up to this point, that this was the perfect embodiment of all the values I held dear, and all the interests that had captured my imagination. It was an outrageously audacious idea, but it seemed that I had found my destiny.

More on this next week!

September 19, 2019

Thingism and Betweenism

I’ve been writing about liminality for my doctorate – that in-between space when a person is not quite one thing any more, but nor are they yet what they are becoming. It often refers to the state of transition during a tribal rite of passage, when the initiand usually absents themselves from their society to go into the wilderness and undergo some kind of trial, like sacrificing a wild animal, to mark their transition from childhood to adulthood.

Richard Rohr

Richard RohrSpaces can also be liminal, as a place of transition. Author and theologian Richard Rohr describes this liminal space as:

“where we are betwixt and between the familiar and the completely unknown. There alone is our old world left behind, while we are not yet sure of the new existence. That’s a good space where genuine newness can begin. Get there often and stay as long as you can by whatever means possible…This is the sacred space where the old world is able to fall apart, and a bigger world is revealed. If we don’t encounter liminal space in our lives, we start idealizing normalcy. The threshold is God’s waiting room. Here we are taught openness and patience as we come to expect an appointment with the divine Doctor.”

For me, my liminal space was the ocean, particularly the Atlantic – my first crossing, and the voyage when I was most keenly aware of being removed from everything that was familiar and thrust into a place of intense fear, leading to exponential growth and transformation.

It strikes me that we generally don’t pay enough attention to these in-between places and states. The last few centuries of reductionist, mechanistic science have trained us to focus on things, rather than the spaces in between them. Even the word “space” is usually defined as empty, unoccupied, an absence rather than a presence.

I wonder what it would be like if we paid more attention to the liminal aspects of reality, and focused on….

…oceans as well as than continents

…relationships as well as than individuals

…boredom/not doing as well as busyness/tasks

…waiting as well as progressing

…who are we when nobody is looking, as well as when everybody is looking.

It feels to me that we need to develop this practice to help bring the world back into balance – to appreciate the yin as well as the yang, the receptive as well as the active, the right brain as well as the left – not just as a spiritual “nice to have” practice, but in order to connect with what science is increasingly telling us is the nature of reality. We inhabit a holistic universe, that can’t be fully explained by cutting it into little pieces, analysing them, and then putting them back together again. It is a synergistic universe, in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. It is a universe composed mostly of dark energy and dark matter, which we can’t see or measure. According to the NASA Science website:

“More is unknown than is known. We know how much dark energy there is because we know how it affects the universe’s expansion. Other than that, it is a complete mystery. But it is an important mystery. It turns out that roughly 68% of the universe is dark energy. Dark matter makes up about 27%. The rest – everything on Earth, everything ever observed with all of our instruments, all normal matter – adds up to less than 5% of the universe. Come to think of it, maybe it shouldn’t be called “normal” matter at all, since it is such a small fraction of the universe.”

How mind-blowing is that?!

So if we think that what we see is all there is (Daniel Kahneman’s WYSIATI), we are very much mistaken. To even begin to grasp the nature of reality, we need to pay attention to the invisible, the interstitial, the liminal. Seems like that’s where all the juicy stuff is. So I’m going to make a conscious effort to be less thingist, and more betweenist.

Other Stuff:

Speaking of liminality, I’ve just finished reading The Salt Path, by Raynor Winn, a wonderful and moving memoir about the journey she and her husband took, walking 630 miles along the South West Coast Path through Dorset, Devon, and Cornwall, after they lost their home and business, and he was diagnosed with a terminal disease. It includes some interesting reflections on the nature of the homeless, those people who have fallen into the liminal spaces of our society. I highly recommend the book (although I found the Audible narration rather annoying – the actor’s voice sounded too old and too posh when I wanted to pretend it was the author speaking).

These thoughts on liminality also remind me of the . So in a way they focus on the things (blocks) rather than the in-betweens (the streets), which is interesting given that, in general, “when processing visual scenes, Westerners attend to salient objects and East Asians attend to the relationships between focal objects and background elements”, so you might have thought they would name the streets, while we in the west would name the blocks. Anyhow, the main point is that there are different ways of looking at things, and holding the awareness that we have been enculturated to see things one way is a crucial first step to being able to see them a different way.

And finally, I’d like to recommend a short-but-sweet book called Liminal Thinking, by Dave Gray. If you don’t have time to read even that (184 pages, with lots of pictures), there is a good Q&A here, a 20-min video here, and my own summary in a previous blog post here.

September 12, 2019

On Existence

I’m grateful for the responses I received to last week’s blog/newsletter, Of Waves and Wonderings. In particular, I’d like to share (with his permission) an exchange of correspondence with a reader in the US.

Hi Roz,

I wanted to let you know how meaningful I found this week’s and last week’s newsletter. Thank you so much for sharing. They arrived in my inbox at the perfect time.

As I’ve come to terms with the trauma in my childhood due to religion, I’ve decided that I don’t believe in God. But I do believe that we are all connected by an unknowable energy – the water you talk about. It’s the energy that delivered a card from my mom into my mailbox just hours after she passed. It’s the energy that inspired a friend to check in with me the day after she died, not knowing she was gone. And maybe another name for that energy is God. So maybe I believe in God after all.

When my Mom passed, she asked that a card with a favorite picture and quote be shared with everyone who knew her. The final paragraph of your newsletter reminded me of the quote.

Thank you for all the positive energy you bring to the world.