Roz Savage's Blog, page 13

August 6, 2020

The Pathways of Purpose

I’ve been thinking a lot about purpose recently, from several different angles, so as I start writing this blog post I feel like a novelist who is embarking on a complicated, multi-stranded plot, with the hope (and not a little anxiety) that I can manage to pull all the plot-lines together at the end. Here goes…

My Purpose

For myself, I feel that purpose has had a massive impact on my trajectory. During my late teens and 20s I had little purpose other than to earn money, buying into the myth that money can make you happy, only to find that any happiness found this way is usually shallow. (Lack of money can make you unhappy, but that is a different thing.)

Abandoning my quest for material wealth, I then set out in search of something that felt more meaningful, and somewhere in the Peruvian Andes, witnessing the retreating glaciers, I found it – my environmental mission. This led to me fully embrace the purpose-led life, dedicating 7 years and 3 ocean crossings to raising environmental awareness. Along the way, I discovered deep wells of courage and resourcefulness that could have remained forever undiscovered if I hadn’t been so incredibly motivated by my goal.

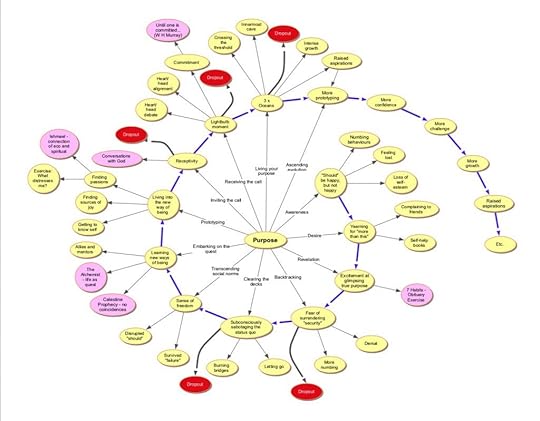

I’ve attempted to plot this journey below (the thing that looks like a psychedelic ammonite), including references to the books that shifted my perceptions in important ways. I hope this wasn’t a purely self-indulgent exercise – I wanted to start exploring whether there might be a universal pattern here, like Joseph Campbell’s monomythic Hero’s Journey, and also to identify the “gumption traps” along the way, i.e. the points at which people decide to stay with the status quo rather than pursue a calling. I hope you might find it interesting and/or helpful.

Is Purpose a Feminist Issue?

Last weekend I was at a (socially-distanced, outdoor) retreat with a group of women, and we had a campfire discussion around purpose. I’m still reviewing the recording, but my initial impression was that, while some women had a specific purpose that they have pursued through their work, purpose can also be less about what you do, than the way that you do it – for example, by taking a mindful, intentional approach to life, or by striving to live more sustainably. Purpose may not manifest in a form that will get you onto the TED stage, but a life can be purposeful none the less.

This made me wonder if there might be a spectrum of purpose, from the grand obsessions of history (Darwin, Einstein, John Nash, Edison, Mallory, Shackleton, etc – mostly men, although Marie Curie, Elizabeth Fry and the Brontës are way up there too) to the equally important but more day-to-day purposes of living a good and decent life, raising well-adjusted children, etc.

(Tangent: “well-adjusted” is such an interesting word… what is it we are adjusting them to? And why did they need adjusting in the first place? More on this later, when we get to Julia Butterfly Hill.)

This led to musings on whether there could be some broad gender correlation, which I suspect would be more cultural than innate, where historically (and still to a large extent, still currently) men have been relatively free to pursue their passions in the laboratory/writing room/Himalayas, while their wives took care of the less glamorous tasks like running the household, making sure everybody got fed, and ensuring that the kids didn’t run completely feral.

But any generalisations relating to gender are risky – just as there is a spectrum of genders, there is also a spectrum of kinds of purpose, from mild to monomaniacal, and it would be hard to distinguish nature from nurture, so I just throw this into the discussion as food for thought, rather than a distinct theory.

Maslow’s Hierarchy and Drug Dealers

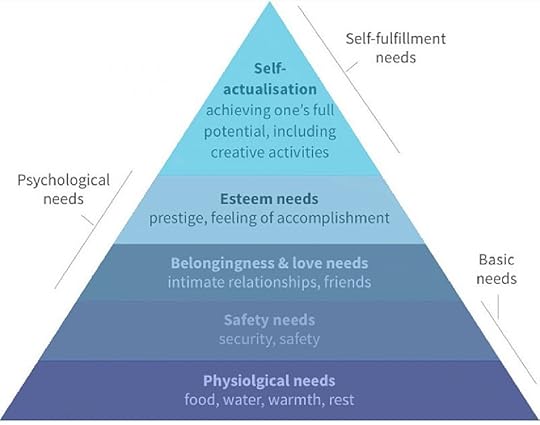

Closely related to purpose, the highest level of the traditional version of Maslow’s hierarchy is “self-actualisation” (although he did, shortly before the end of his life, add the further level of “self-transcendence”, but that’s not relevant to my present point).

Maslow defined self-actualisation as:

“The desire for self-fulfilment, namely the tendency for him [the individual] to become actualized in what he is potentially. This tendency might be phrased as the desire to become more and more what one is, to become everything that one is capable of becoming.”

In my experience, it is a sense of purpose that unlocks this potential, and enables the individual (me) to overcome (my) self-limiting beliefs and rise to challenges.

But Maslow’s hierarchy has been somewhat misinterpreted and abused over the decades. He saw it as a staircase, not a pyramid. He saw all the levels being available to everyone, and also included the possibility that we move up and down between the levels rather than it being a one-way progression up the hierarchy.

But Maslow’s hierarchy has been somewhat misinterpreted and abused over the decades. He saw it as a staircase, not a pyramid. He saw all the levels being available to everyone, and also included the possibility that we move up and down between the levels rather than it being a one-way progression up the hierarchy.

True, it’s hard to focus on self-actualisation when you’re starving or homeless, but in the original version there was no implication of elitism. By morphing the staircase into a pyramid, subsequent commentators introduced an element of exclusivity, as if the higher levels are available to fewer people than the lower levels. It’s time we re-democratised Maslow’s model.

Society has also introduced judgement around how people meet their needs. I was talking recently with a new collaborator, who introduced me to a really interesting idea: to focus on changing the product, rather than the behaviour. Drawing on her experience in the criminal justice system, she pointed out that drug dealers (the successful ones, anyway) have a talent for attracting customers, negotiating, and closing a deal. Also, given their life circumstances, drugs are an entirely logical choice of product: easily available, high profit margins, ready market.

So rather than getting them stacking supermarket shelves, why not take their talent, and turn it to a more beneficial (and legal) product – like cars, real estate, or antiques? After all, the illegality of drugs is a cultural decision, not a natural law. There are many other professions that exploit people’s weaknesses, without being illegal. (Please note: I’m not advocating for the legalisation of drugs, although I can see arguments in favour as well as those against. I’m just saying that illegality is a societal choice.)

Julia Butterfly Hill and the Joys of Not Being “Well-Adjusted”

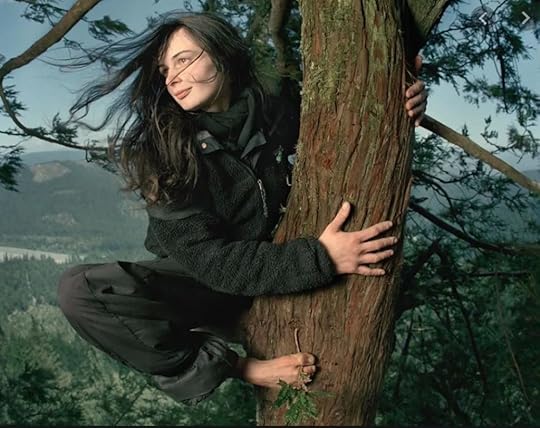

Last week I was interviewing Julia Butterfly Hill for the second edition of The Gifts of Solitude (intended to be published post-COVID, whenever that may be). If you don’t know Julia’s incredible story, I highly recommend her book, The Legacy of Luna, about the two years she spent living in a redwood tree to protect it from loggers, enduring storms, biting cold, and frequent harassment by the loggers, who sometimes even used helicopters to try and scare her out of the tree.

Last week I was interviewing Julia Butterfly Hill for the second edition of The Gifts of Solitude (intended to be published post-COVID, whenever that may be). If you don’t know Julia’s incredible story, I highly recommend her book, The Legacy of Luna, about the two years she spent living in a redwood tree to protect it from loggers, enduring storms, biting cold, and frequent harassment by the loggers, who sometimes even used helicopters to try and scare her out of the tree.

And this brings me back to “well-adjusted” children, as mentioned earlier. She told me how the things that she was always being scolded for as a child, were actually the things that enabled her to do what she did – such as caring passionately about nature, being noncompliant and strong-willed. When society tries to create obedient, compliant children, are we actually crushing the very qualities that could help lead them to their purpose?

Rebellious children may be difficult, but how do we know if the thing we try to change about them is the very thing that might help them find their purpose? (Easy for me to say, I know.) Socialisation is important, but how do we avoid socialisation becoming homogenisation? I have no idea, and leave these questions to people who know what they’re talking about, like Sir Ken Robinson in his classic TED Talk, Do Schools Kill Creativity? – which has now racked up an unbelievable 66 million views.

Julia and I also laughed about the fact that, both being preacher’s kids and having spent much of our early adulthood rebelling against that inheritance, we have both ended up preaching, albeit in a non-religious context. Maybe the apple doesn’t fall so far from the tree after all. Even if neither of us inherited our parents’ religious convictions, maybe we did internalise the message that life can be enriched by a sense of vocation, which is just another word for purpose.

Conclusion

So, after all these half-baked theories, cultural cross-references, and random tangents, have I managed to get any closer to an analysis of purpose? Good question. Here’s what I think I know.

For me, personally, having the grand purpose of rowing across oceans to raise environmental awareness has added immeasurably to my life, introducing me to people, places, and inner resources that I would never have otherwise encountered.

But this just happened to be my path in this lifetime. And there are many other paths, which are also purpose-led, and equally important and valid. Society may still bestow greater rewards on the people who pursue purposes that have historically been associated more with the male of the species, such as exploration, science, business and politics, but purpose can also be a quiet, modest, non-attention-seeking thing that finds expression through daily acts of kindness, caring, and mindful living.

Ultimately, I would suggest that having a sense of purpose is an entirely subjective experience. If we know what our values and principles are, and live in accordance with them, then we are following our purpose. And we know the feeling when we are out of integrity with our purpose – if everything looks great on paper, but inwardly we know something doesn’t feel right – then it’s time for a rethink.

Writing this blog post has helped me clarify why I usually feel embarrassed when somebody praises what I’ve done (all that ocean-rowing malarkey) or says that they could never do it. If they had been in my shoes, with the perfect storm of influences and ideas all colliding at once to make the absurd idea of rowing across oceans seem like a good one, they would have made the same choice. And, like me, they would have set out not knowing if they could do it, and somewhere along the way they would have found out that they could.

I simply followed my intuition or, as I prefer to think of it, the calling of my soul. And that is all purpose is.

Other Stuff:

TEDxStroudWomen: The deadline for speaker applications was midnight last Friday, and we received an incredible 60+ applications in the last 36 hours, bringing our total to 84. The committee now has the unenviable task of winnowing these down to a shortlist of 20 or so, and then down to our final 9.

TEDxStroudWomen: The deadline for speaker applications was midnight last Friday, and we received an incredible 60+ applications in the last 36 hours, bringing our total to 84. The committee now has the unenviable task of winnowing these down to a shortlist of 20 or so, and then down to our final 9.

We are still on the lookout for sponsors, so if you know companies, philanthropists, or anybody else who might want to throw money our way, especially if they are Gloucestershire-based, please let me know.

And if you want to be sure of an invitation to buy tickets, whether in real life or virtual, depending on the COVID situation come 29th November, please sign up for our newsletter on the website. Thanks!

July 30, 2020

As Within, So Without

I wonder what happens to you when you think about this coming decade.

What images flicker through your mind’s eye? Do you see COVID dragging on indefinitely, global recession, ongoing civil unrest, the rise of populism, Trump clinging to power, the Amazon burning, climate change starting to bite harder?

Or do you see COVID fading into memory, communities being rebuilt, many forms of inequality being surfaced and addressed, COP26 delivering unprecedented commitments to carbon reductions, humanity rising to the challenge of climate change?

And how do these thoughts make you feel? Even just reading my words, even though they are not your thoughts but mine, maybe the gloomy paragraph made you feel fearful, constricted, tense. And maybe the more optimistic paragraph made your shoulders relax, your chest expand, your spirits rise.

Which paragraph made you feel empowered to do something? Which paragraph helped you see possibilities, rather than obstacles? Which paragraph made you feel more creative, resourceful, inspired?

Of course, it’s never that simple. If you’re like me, you have days when you are glass half full, and other days when you are glass half empty. You might flip-flop between the two states several times in a day, or even in an hour, depending on which news headline you have just read. Sometimes everything seems possible, sometimes everything seems impossible.

Interviewed by TED’s Chris Anderson early in the COVID lockdown, author Elizabeth Gilbert observed that when asked what the long-term impacts of the COVID lockdown would be, her optimistic friends foresaw a utopian outcome, while her pessimistic friends foresaw a dystopian one.

Interviewed by TED’s Chris Anderson early in the COVID lockdown, author Elizabeth Gilbert observed that when asked what the long-term impacts of the COVID lockdown would be, her optimistic friends foresaw a utopian outcome, while her pessimistic friends foresaw a dystopian one.

In other words, and at the risk of stating the obvious, none of us know for sure what the future holds, so whatever we think we foresee is no more than a projection into the future of our personal worldview. And because our personal worldview is derived from what has happened in our past, our past (or, more to the point, how we choose to interpret our past) becomes the primary determinant of our expectations of the future.

And our expectations of the future have a better-than-random chance of becoming our actual future. Whether you come at this question from the spiritual, psychological or even the quantum perspective, perception shapes reality. (Stanford researchers say so.)

Here’s my personal take on it. When I think back over my life, I can conjure up many examples of times when it felt like everything was going to hell. Whether it was an expedition, or a relationship, or an accident that sent everything flying sideways at high speed, there have been times when I fought reality, feeling indignant and/or outraged that things hadn’t turned out as I expected. And yet I can look back now, and see how those events have shaped me for the better, forcing me to become stronger, more resourceful and more courageous than I would otherwise have been.

Here’s my personal take on it. When I think back over my life, I can conjure up many examples of times when it felt like everything was going to hell. Whether it was an expedition, or a relationship, or an accident that sent everything flying sideways at high speed, there have been times when I fought reality, feeling indignant and/or outraged that things hadn’t turned out as I expected. And yet I can look back now, and see how those events have shaped me for the better, forcing me to become stronger, more resourceful and more courageous than I would otherwise have been.

I can’t say for sure that there was a divine pattern at work to give me the experiences that I needed in order to learn what I needed to learn, but sometimes it has definitely felt that way. The principle that “everything happens for a reason” may or may not be true – no way of knowing – but pending proof either way, it definitely makes me feel better to believe that there is some rhyme or reason behind the perceived hardship, and one day I will be able to look back and be grateful for it.

As Max Ehrmann puts it in Desiderata, the words of which I have hanging in my bathroom:

“Even though it may not be clear to you, no doubt the universe is unfolding as it should.”

I perceive myself as a lucky person. And you could justifiably say that it’s easy for me to see myself that way – I am a well-educated person, born into a normally-abled, white-skinned body in a developed country, who is straight and cis and otherwise remarkably unremarkable. And I acknowledge all that privilege. But there are others, who on paper appear to be every bit as privileged as me, who see themselves as unlucky, and who approach the world with an attitude of fear and apprehension rather than faith and agency, while there are still others, who appear to have been dealt a less favourable hand, who transcend their circumstances to create an amazing life (like Nick Vujicic, born with no limbs).

There is a kind of infinite regression problem here – how do you become the kind of person who perceives opportunity rather than obstacles? If the accident of birth or early formative experiences have led to a very rational belief that the world is hostile and harsh, how do you bootstrap your way out of that mindset and into one that is more positive?

It’s learnable. This article in The Week on how to become luckier offers some very practical pointers to start.

It’s learnable. This article in The Week on how to become luckier offers some very practical pointers to start.

Maximize opportunities: Keep trying new things.

Listen to hunches: Especially if it’s an area where you have some experience, trust your intuition.

Expect good fortune: Be an optimist. A little delusion can be good.

Turn bad luck into good: Don’t dwell on the bad. Look at the big picture.

Even when everything seems hopeless, scan your inner landscape for the most positive thought you can find and grab onto it. It’s a lifeline you can use to haul yourself out of the innermost cave.

“When you reach for the thought that feels better, the universe is now responding differently to you because of that effort. And so, the things that follow you get better and better, too. So it gets easier to reach for the thought that feels better, because you are on ever-increasing, improving platforms that feel better.” – Abraham-Hicks

The truth is, we don’t yet fully know how the universe works. In our 21st century arrogance and hubris, we might think we’re tremendously advanced, but heed the words that may or may not have been uttered by Lord Kelvin in 1900…

“There is nothing new to be discovered in physics now. All that remains is more and more precise measurement”

…mere months before Max Planck described his famous postulate, thereby sowing the first seeds of the vast new field of quantum physics.

At the cutting edge of the new science, Don Hoffman’s work (summarised in an earlier blog post) suggests that reality is not as we perceive it, but that “fitness” beats “truth” every time (fitness being perceptions that support the ability to survive for long enough to pass along one’s genes, versus truth, or objective reality). He proposes that reality is formed by a network of conscious agents, and that consciousness may be the invisible ground out of which the material world emerges, rather than vice versa. So it doesn’t seem to be a leap too far to assume that the nature of that consciousness would have a powerful influence on its material manifestation.

So, to circle back to my hero Christiana Figueres, quoted above, and her story behind the success of the 2015 Paris climate change negotiations, maybe there is some truth in the dictum from The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus:

So, to circle back to my hero Christiana Figueres, quoted above, and her story behind the success of the 2015 Paris climate change negotiations, maybe there is some truth in the dictum from The Emerald Tablet of Hermes Trismegistus:

“As above, so below. As within, so without.”

(See also the Cherokee story of “which wolf are you feeding?“)

All in all, there is a growing body of evidence from both science and spirituality that our thoughts shape our reality. Even on the most pragmatic level, think back to those paragraphs at the start of this blog post, and reflect on how the negative thoughts impacted your energy levels compared with the positive thoughts. Even if you don’t buy into the notion that thoughts shape reality, actions certainly do, and you’re more likely to take positive action if you are feeling energetised rather than despairing.

So, whichever way you look at it, optimism can only be a good thing – not the bright-siding, wilfully blind kind of Pollyanna optimism that pretends that everything is just lovely in the garden, but the gritty, determined, roll-your-sleeves-up kind of optimism that gets stuff done.

Wishing you a wonderful week of positivity.

July 23, 2020

If You’re Not Living On The Edge…

“Evil can hide in systems much more readily than in individuals.”

Richard Rohr writes this in reference to Francis and Clare of Assisi, who he says “found both their inner and outer freedom by structurally living on the edge of the inside of church and society”.

I feel that this edge-ness has a lot to do with where we are as a world right now, in relation to racial justice, COVID, and climate change. I will attempt to explain.

Richard Rohr

Richard RohrRohr goes on to say:

“By “living on the edge of the inside” I mean building on the solid Tradition (“from the inside”) from a new and creative stance where you cannot be co-opted for purposes of security, possessions, or the illusions of power (“on the edge”).”

In other words, they had one foot in each of the two worlds: they had one foot in the old order, because if they left that order entirely, they couldn’t be a force for change. But they also had one foot in the unknown realm of newness, outside of the status quo, from which they could objectively see the strengths but also very much the weaknesses of the old system, and start to imagine a better new world.

The problem for people who have both feet squarely in the old order is that they often can’t see the need or potential for a new and better way of doing things. While Otto Scharmer says (in the downloadable pdf of the introduction to his excellent book, Leading from the Emerging Future) that the old civilisation is “collectively creating results that nobody wants”, I don’t think it’s quite accurate to say that nobody wants them. There are clearly some somebodies who do want those results, because the results suit them just fine, thank you very much.

Systems often embed old and outdated moral codes. We inherited them from an era when there was less awareness and less respect for the rights of our fellow humans and of nature, but because we are so embedded in the systems, and “it has always been that way”, those of us who have nothing to complain about are often blind to their flaws. If the injustices are not part of our daily experience, we don’t see what we don’t see.

A quote that has been widely used in the context of racial bias in the American (so-called) justice system is, “the system isn’t broken; it was built to work this way”. This is how faulty old systems like discrimination based on race or gender, or rapacious forms of capitalism, manage to perpetuate themselves. The people who have acquired power within that system have less than zero incentive to change the system, and the people who want to change it don’t have the power to do so.

Conversely, nor will having both feet in the new order generate impetus for change. It may enable enlightened individuals to live in an off-grid utopia, but if they have totally opted out of the mainstream to sit on a metaphorical mountaintop, their influence will be mystical rather than material.

In a blog post I wrote in June about Fairness, Floyd, Cooper, Cummings and Chaos, I mentioned that, according to chaos theory, change requires both a shock to the existing system, plus a powerful point attractor outside the existing regime. But there is such a thing as “too far outside” the existing regime. If those inside the regime can’t even see the new alternative, they’re not going to gravitate towards it in the numbers necessary for it to gain traction.

And so we come back to the edge. One foot in the old, one foot in the new.

Mitchell Waldrop in his book Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos describes this edge thus:

“Right between the two extremes [order and chaos] … at a kind of abstract phase transition called the edge of chaos, you also find complexity: a class of behaviours in which the components of the system never quite lock into place, yet never dissolve into turbulence, either. These are the systems that are both stable enough to store information, and yet evanescent enough to transmit it. These are systems that can be organized to perform complex computations, to react to the world, to be spontaneous, adaptive, and alive.”

Put more simply, the edge is where the cool stuff happens – creativity, imagination, innovation, envisioning.

If chaos theory is a bit too cerebral for your tastes, Sharon Blackie puts the same idea beautifully and in more embodied fashion in If Women Rose Rooted:

If chaos theory is a bit too cerebral for your tastes, Sharon Blackie puts the same idea beautifully and in more embodied fashion in If Women Rose Rooted:

“I have always been drawn to the edges of things, the places where two things collide. Where bog borders riverbank, where meadow merges into forest. Where you stand in the margins of what is behind you and look out across the threshold of the future. The brink of possibilities – will you cross? Edges are transitional places; they are also the best places from which to create something new. Ecologists call it the ‘edge effect’: at the convergence, where contrasting ecological systems meet and mingle… Those of us who live here must be comfortable with storms and with change, for it is on these unsettled, unsettling edges that we will hear the Call which launches us on our journey. And though we can never quite be sure what that journey will involve, we know that new possibilities may be created only if we surrender to uncertainty.”

And with that last word, she alerts us to the dangers. Edges may be where the cool stuff happens, but they are also, well, more edgy.

“When we heed that Call and step off the edge, thinking to firmly set foot on the path which lies ahead of us, to strike out confidently on our new pilgrimage – we may instead find ourselves losing our footing, plummeting down into the dark.”

And that is the invitation of these times, as we emerge (for now) from COVID lockdown, with fundamental problems being (re)surfaced, demanding resolution. We know that evil is hiding in many of our old systems and that, in fact, those systems were built to work that way. A hasty retrofit of wokeness just isn’t going to do the job.

The good news, as I see it, is that while evil may hide in systems, solutions hide in communities. When we bring together small groups to talk openly in an atmosphere of trust, even if that trust has to be slowly earned over time, we start to find a way forward towards a world that works for all.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” — Margaret Mead

We have to stand on that scary edge, with one foot in the old order, and one planted firmly – or more likely, precariously – in the new. And together we have to hoist that edge onto our collective shoulder, and drag it, maybe bending under its weight, towards a new, better, more just and equitable horizon.

We don’t know what the future holds. So we have to create the path by walking – and talking – together.

July 16, 2020

White Lies and the Branches on the Tree of Systemic Racism

“It’s like a tree with branches, that if you cut off one branch, don’t mean the damn tree going to die. It’s just going to grow another branch. And that’s what’s happening. We need to find the root of all this.” – Joanne Bland, co-founder of the National Voting Rights Museum in Selma, Alabama

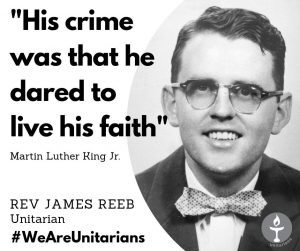

I’ve just finished listening to White Lies, an excellent story of investigative journalism by two white Alabamians into the case of Rev. James Reeb, a Unitarian minister who in March 1965 left his wife and four young children at home in Boston, to travel to Selma in response to Martin Luther King’s appeal for clergymen to come and support the cause after the unprovoked Bloody Sunday attack on nonviolent activists on Edmund Pettus Bridge. Less than 24 hours after arriving in Selma, Reeb was leaving a restaurant with two other clergymen (all of them white sympathisers with the civil rights cause) when he was set upon by a group of four or five white men, one of whom hit him hard in the side of the head with a billy club, with a sound that reverberated down the street. A melée ensued, in which all three clergymen were beaten by this group of white locals. Reeb died two days later as a result of his head injury. Three white men were brought to trial, but were acquitted by an all-white jury.

White Lies follows Chip Brantley and Andrew Beck Grace as they spend several years trying to find out what really happened. They are relentless in their pursuit of the truth, rummaging around in sheds of old files, knocking on doors, interviewing anybody who will speak to them (and many people won’t). Nearly 55 years after the fact, the trail couldn’t be much colder, and many potential witnesses are dead, but their doggedness pays off.

White Lies follows Chip Brantley and Andrew Beck Grace as they spend several years trying to find out what really happened. They are relentless in their pursuit of the truth, rummaging around in sheds of old files, knocking on doors, interviewing anybody who will speak to them (and many people won’t). Nearly 55 years after the fact, the trail couldn’t be much colder, and many potential witnesses are dead, but their doggedness pays off.

Whether you are in it for the racial issues it raises, or because you like a good murder mystery, or both, It’s well worth listening to all seven episodes, or reading the transcripts if you prefer, but the fully produced audio production really is worth experiencing – hearing the voices and accents of the interviewees brings it vividly to life in a way that the written word simply can’t.

I don’t want to say too much more about it, for fear of spoiling it for you, but I will just explain what inspired the name of the series. Almost immediately after Reeb’s murder, a story started that he had not died of the injuries caused by the initial attack, but had been killed in the back of the ambulance while on his way to the nearest neurological unit, in Birmingham, Alabama. The lie suggested that the civil rights movement needed a white martyr (because a lost white life would get more publicity than a lost black life), and they seized their opportunity with the already-injured Reeb.

The convenient lie quickly gained traction, overriding the inconvenient truth of the racism that ran so deep through white Alabamian society. Even witnesses, who had seen the truth with their own eyes, lied to the authorities out of fear of the consequences if they told what had really happened.

The convenient lie quickly gained traction, overriding the inconvenient truth of the racism that ran so deep through white Alabamian society. Even witnesses, who had seen the truth with their own eyes, lied to the authorities out of fear of the consequences if they told what had really happened.

This is one story, about one incident, that killed one man, many decades ago. But the uncomfortable question is still with us, whether we relate it to race, or economic inequality, or environmental destruction:

What are the lies we tell ourselves in order to sleep at night? What untruths are we choosing to believe, because they enable us to maintain the perception of ourselves as good people? If we truly are good people, what do we need to open our eyes to, and be willing to embrace the discomfort, and have the brave conversations, and be open to listening and learning, in order to heal the wounded human psyche?

These aren’t just rhetorical questions. Please really think about them, and read about the experiences of others who may not share your skin colour, or educational advantages, or economic comfort. I’m aware that I’m asking you to get outside your comfort zone, and you may not appreciate that (and may not appreciate me for inviting you to do it). But this really, really matters.

“Do not be a silent witness. Just do it. You have to be the one.” — Joanne Bland

Joanne Bland on the right. The guy in the middle looks vaguely familiar… (40th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, 2005)

Joanne Bland on the right. The guy in the middle looks vaguely familiar… (40th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, 2005)Other Stuff:

A quick tech question: a correspondent has said that the font of my newsletter appears so small on her phone that it is difficult to read. Are other people having that same problem?

July 9, 2020

Question Thinking: From Judging to Learning

In the introduction to Change Your Questions, Change Your Life, author Marilee Adams writes:

“Questions open our minds, our eyes, and our hearts. With our questions we learn, connect, and create. We are smarter, more productive, and able to get better results. We shift our orientation from fixed opinions and easy answers to curiosity, thoughtful questions, and open-minded conversations, lighting the way to collaboration, exploration, discovery, and innovation. I have a vision of workplaces and a society—of individuals, families, organizations, and communities—that are vibrant with the spirit of inquiry and possibility.”

She goes on to explore this via a fictional account of Ben Knight, whose career is hitting the rocks, and it looks like his marriage of less than one year might be doing the same. Thanks to a coach called Joseph, he switches from looking for the right answers to seeking better questions. I don’t think it’s a massive spoiler to say that this shift in perspective transforms both his job and his relationship.

Like many modern parables, Change Your Questions isn’t going to win prizes for literary lyricism any time soon, but it does convey an important message that is very much in alignment with my exploration of leadership for uncertain times like these. Old-style, authoritarian leaders considered facts and arrived at answers. New-style (or “teal”) leaders ask questions in order to unlock the intelligence of the team. Question Thinking (QT) is a system of tools for transforming thinking, action, and results through skilful question-asking—questions we ask ourselves as well as those we ask others.

“It is not the answer that enlightens, but the question.” – Eugene Ionesco

According to Arnold Toynbee, civilisations fail when they start to believe that the same old winning formula can be applied to new problems. Past successes blinker their approach to the current reality. But, as Marshall Goldsmith pithily puts it in his eponymous book, What Got You Here Won’t Get You There, at some point, the old approaches stop working, and stubbornly persevering in using them leads to collapse, individual and/or societal. It seems that asking questions rather than leaping to find answers could get us out of this bind.

The crux of the matter is to adopt an attitude of curiosity, rather than leaping to conclusions. Carol Dweck might call this adopting a growth mindset rather than a fixed mindset. Riane Eisler might call it a partnership paradigm rather than a dominator paradigm. When you’re in “judging” mode, there is an arrogant implication that you know best and hence, by implication, others don’t.

“The clues that I was in Judger were in my own moods and attitudes, which I’ve learned to associate with Judger— self-righteousness, arrogance, superiority, and defensiveness.”

When you switch into Learner, you open the door to co-creation and synergy, creating the possibility of working with others such that the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts. Everybody feels more engaged and empowered, and creativity is unleashed. The dynamic evolves from the zero-sum game of a power struggle into the spirit of being fellow travellers on a journey into the unknown.

When you switch into Learner, you open the door to co-creation and synergy, creating the possibility of working with others such that the whole becomes greater than the sum of the parts. Everybody feels more engaged and empowered, and creativity is unleashed. The dynamic evolves from the zero-sum game of a power struggle into the spirit of being fellow travellers on a journey into the unknown.

“Change your questions, change your thinking. Change your thinking, change your results. If only for a second, you become an observer watching a movie of your life. You simply notice whatever moods, thoughts, and behaviours are going on, without interpretation or judgment. That mindfulness sets the stage for just accepting what is, which also sets the stage for change, for choosing the mindset you’re going to operate from.”

Not only does the Judger mindset have adverse impacts on our relationship with others, it can also have adverse impacts on our relationship with ourselves. You can probably think of judgemental people in your life. Chances are, you don’t particularly like being around them. But have compassion for them too, because whatever judgement they show towards you, they probably show 10x towards themselves.

“Judger has two faces, one being judgmental toward ourselves, the other being judgmental toward others. The results can look quite different, but they come from that same judgmental, critical place in our thinking.”

Just to be clear, we do all judge. It’s human nature. When we meet somebody new, we quickly arrive at an initial assessment about their character, trustworthiness, likeability. The point is not to mistake judgement for truth.

Also, there is a difference between judgement and discernment. Once we get to know that person better, we might find that there are aspects of their character that we don’t feel particularly comfortable with. (No doubt Jeffrey Epstein was very charismatic on first acquaintance, but….) We may then wisely choose not to have anything to do with them. Judgement in this context is no bad thing, and it is known as discernment.

When I look at the divides that have riven many of our societies recently – Remainers vs Brexiteers, Democrats vs Republicans, the divides based on race, religion, region, and so on – I see so much judgement, so much “them and us”, so much disgust. Any comment that includes the words “these people” is coming straight from judgement. And that just creates more of the same.

“Learner begets Learner. And Judger begets Judger.”

So what would happen if we got curious, and went from Judger to Learner? What if we asked questions to understand better why people feel as they feel, believe as they believe? We’d probably find that we have a lot more in common than we think. We could defuse this conflict, and start to heal the wounds.

There is a danger – that I’m guessing I’m not the only one to have fallen into this – that we believe the latest book we read really is the answer to all that ails the world. But Question Thinking really does have power – the power to heal division, and maybe even the power to save civilisation as we know it.

What questions are you going to ask today?

A helpful resource is the Choice Map above, downloadable here. Many more resources on the Inquiry Institute website.

Other Stuff:

TEDxStroudWomen is gathering momentum. That’s not me giving a TED Talk (in fact, as curator of the event I am not allowed to speak, so will be keeping my mouth shut, other than emcee-ing the event). It’s our TEDx committee having a recce at the Sub Rooms in Stroud yesterday, checking out the lighting, sound, and stage setup. Jerry the techie found a TEDx logo to project onto the screen, and suddenly it all seemed very real!

We are now open for applications from aspiring speakers. As the video below says, you don’t have to be an experienced speaker – you just need a big idea worth sharing. We will support you every step of the way from selection to stage with a series of workshops with professional speaking trainers. Please apply, and/or spread the word!

Angela Madsen: Following Angela’s tragic loss at sea, please remember about the fundraiser on GoFundMe to cover the cost of repatriating Angela’s body, and recovering her boat with the film footage on board. Please do what you can to support this cause, and check out Angela’s website for news updates.

July 2, 2020

The F-word: Why “Feasible” Will Never Get Us Where We Need To Go

I was reading this article about climate in The Guardian, and one word leaped out. Feasible.

“Chris Stark, chief executive of the CCC (Committee on Climate Change), defended the logic behind its 2050 target, which he said was based on “detailed considerations of the climate science, based on the IPCC’s work, the international context, including the Paris agreement and ‘equity’ considerations, and the feasible speed and cost at which UK emissions can be reduced”.”

While I’m all for pragmatism, I’m not for using feasibility as an excuse for wishy-washy targets and procrastination. If you were a smoker and your doctor told that you had emphysema, and would die in six months if you carried on smoking, I don’t think you would take an incremental approach to reducing your consumption of cigarettes. I think it would scare the living daylights out of you, and you would stop immediately.

As the late, great Polly Higgins used to say, if you heard your neighbours beating their kids, you wouldn’t go round and ask them to beat the kids a little less. You would ask them to stop.

If we’re going to talk about feasibility, let’s look at some of the facts that we might once have thought were unfeasible.

Temperatures in the Arctic Circle hit an all-time record on 20th June, reaching an astonishing 38C (100F) in Verkhoyansk, a Siberian town.

Temperatures in the Arctic Circle hit an all-time record on 20th June, reaching an astonishing 38C (100F) in Verkhoyansk, a Siberian town.

Wildfires are ravaging parts of the Arctic, with areas of Siberia, Alaska, Greenland and Canada engulfed in flames and smoke.

Greenland’s ice sheet shrank more in July 2019 than in average year.

Do unfeasible scenarios call for feasible solutions? I don’t think so.

This article, written in May, reports on a drop of 4-8% in global carbon emissions due to the coronavirus, equivalent to losing the entire energy demand of India, and sunnily predicts, “This will feed through to large falls in CO2.”

Unfortunately, it didn’t.

The readings at the Mauna Loa observatory showed a rise of nearly 2 parts per million (ppm)between June 2019 and June 2020 (taking us close to 420ppm, which is 140ppm above pre-industrial levels, and 70ppm above the theoretical long-term liveable limit), implying either that there is a significant time lag between a drop in emissions and a drop in atmospheric CO2, and/or the feedback loops that have already been set in motion more than outweigh a temporary reduction in emissions.

We are currently on track for more than 3 degrees C of warming. Might not sound like much, but it really is. This is quite a cool website that models the difference between 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees of climate change, and in places 3 degrees or more. Way less cool, but way more bone-chilling, is this piece describing the impacts at increasing temperature bands. Here’s a sample:

We are currently on track for more than 3 degrees C of warming. Might not sound like much, but it really is. This is quite a cool website that models the difference between 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees of climate change, and in places 3 degrees or more. Way less cool, but way more bone-chilling, is this piece describing the impacts at increasing temperature bands. Here’s a sample:

“BETWEEN TWO AND THREE DEGREES OF WARMING

Up to this point, assuming that governments have planned carefully and farmers have converted to more appropriate crops, not too many people outside subtropical Africa need have starved. Beyond two degrees, however, preventing mass starvation will be as easy as halting the cycles of the moon. First millions, then billions, of people will face an increasingly tough battle to survive.”

It’s not a cheerful read. You have my permission to pour yourself a stiff drink afterwards, to toast the end of civilisation as we know it.

Whether or not you believe that all of climate change is caused by humans, if there is anything at all we can do to slow it or stop it, we should be doing it, no matter how feasible those measures might be.

Our response to COVID, by slamming the brakes on the global economy, was unfeasible. But we did it anyway.

The estimated cost to the global economy of COVID is between $3.3 trillion and $82 trillion over the next 5 years. Reporting in Nature, researchers found that if human beings fail to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to the levels designated in the Paris Agreement, the economic cost would range from $150 trillion to as much as $792 trillion by 2100. (If you want to really depress yourself, this article implies that the eventual cost of climate change, if you want to try and put a value on it in terms of money, could be “all of it” – as in, no humans, no economy.)

We didn’t see COVID coming (although arguably we could/should have done). But for sure we can see climate change coming. But it’s a quirk of human psychology that we prioritize the loud, proximate, and urgent over the silent, distant, and long term. (See George Marshall’s excellent book, Don’t Even Think About It: Why Our Brains Are Wired To Ignore Climate Change.) This doesn’t mean that the creeping threat of a warming world is any less lethal. The human brain, which has created so much and benefited so many, also suffers from numerous cognitive biases that impede our ability to understand exponential change leading to existential risk. These failures of rationality could prove to be our fatal flaw. This, and the immense hubris of our collective, self-important human ego.

We must begin with the end in mind (to channel Steven Covey) – not looking at where we go from here, but rather envisioning where we as a species want to be 50 or 100 years from now, and work backwards from there (akin to the obituary exercise that changed my life). I, for one, want to live in a world where we still have ice caps and healthy oceans, and where “Amazon” isn’t just a world-dominating retail company.

I think it was Christiana Figueres who said that we must do, not what is feasible, but what is necessary. We really are up against the F-word. If we don’t get past a lame, flaccid requirement of feasibility, then we are well and truly f***ed.

Other Stuff:

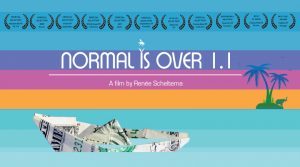

On Monday night, the Sisters had a virtual screening of Normal is Over 1.1 (the updated edition of the 2015 documentary), followed by a Q&A with the filmmaker, Renee Scheltema. As well as the original lineup of Charles Eisenstein, Bernard Lietaer, Vandana Shiva, Paul Gilding, Naomi Oreskes, Michael Mann, Ta’Kaiya Blaney, Lester Brown, etc., the film now also includes an interview with Kate Raworth about her Doughnut Economics model. Comments after the film included: “I laughed and I cried. . . I can’t believe only 3 percent of the animals on the planet are wild . . . In 45 years we have wiped out 62% of all wild animals . . . I agree we have lost connection to nature and community through a money focussed economy . . . there is SO much in this film, informationally, emotionally and visually. I am going to watch it again to fully absorb all of its richness… I say what if community spirit was created by everyone essentially working as nature workers and we regenerate our Mother Earth through a nature currency, not a money one… This film really brings everything together in one place, and shows the connections.”

On Monday night, the Sisters had a virtual screening of Normal is Over 1.1 (the updated edition of the 2015 documentary), followed by a Q&A with the filmmaker, Renee Scheltema. As well as the original lineup of Charles Eisenstein, Bernard Lietaer, Vandana Shiva, Paul Gilding, Naomi Oreskes, Michael Mann, Ta’Kaiya Blaney, Lester Brown, etc., the film now also includes an interview with Kate Raworth about her Doughnut Economics model. Comments after the film included: “I laughed and I cried. . . I can’t believe only 3 percent of the animals on the planet are wild . . . In 45 years we have wiped out 62% of all wild animals . . . I agree we have lost connection to nature and community through a money focussed economy . . . there is SO much in this film, informationally, emotionally and visually. I am going to watch it again to fully absorb all of its richness… I say what if community spirit was created by everyone essentially working as nature workers and we regenerate our Mother Earth through a nature currency, not a money one… This film really brings everything together in one place, and shows the connections.”

Numerous Sisters are now in turn hosting their own screenings. Please watch the film, and hold on right to the end, where you’ll find the calls to action. And maybe you’ll want to host your own screening – if so, let me know, and I’ll connect you with the filmmaker so you can let her know.

Angela Madsen:

Further to last week’s blog post reporting the sad loss of a legendary ocean rower, and paying tribute to her immense courage, I’d like to add that a fundraiser has been started on GoFundMe to cover the cost of repatriating Angela’s body, and recovering her boat with the film footage on board. Please do what you can to support this cause, and check out Angela’s website for news updates.

You may also want to take a look at the wonderful obituary that appeared on CNN, including a video of Angela speaking on camera, and a very moving tribute to Angela written by Naïma Hana Simi, the mother of Angela’s filmmaker, Soraya. It’s a beautiful piece and I highly recommend it.

June 25, 2020

In Memory of Angela Madsen, Ocean Rowing Legend

I was tremendously saddened to hear that Angela Madsen has died during her first solo row, an attempt to become the first paraplegic and oldest woman to row from California to Hawaii. She was about half way through her journey, at the furthest point from land, and had just celebrated her 60th birthday at sea.

Angela Madsen with New Zealand rower Tara Remington, at the Pete Archer Rowing Center in Long Beach, on May 15, 2014. (Photo by Sean Hiller/ Daily Breeze).

Angela Madsen with New Zealand rower Tara Remington, at the Pete Archer Rowing Center in Long Beach, on May 15, 2014. (Photo by Sean Hiller/ Daily Breeze).After Angela failed to respond to text messages on Sunday, Soroya Simi, who was making a film about Angela’s bid, contacted the US Coast Guard. They sent a plane, and the crew spotted Angela in the water, still tethered to her boat, apparently lifeless. Her body was later retrieved by a cargo ship.

Angela had told her wife, Debra, that she was going to make some repairs or adjustments to the sea anchor deployment apparatus on the bow of the boat, which would require her to go into the water. I was always very careful about going into the water (apart from the one time when I wasn’t, and very nearly came unstuck and lost my boat: see The Stupidest Thing I Have Ever Done), and I would imagine that Angela would have been at least twice as careful as I was, having limited use of her legs after being left paraplegic by a botched back surgery, intended to remedy a basketball injury, in 1993. I am sure she would only have got into the water if the repair was absolutely necessary.

We will probably never know exactly what happened. It’s not much fun trying to do repairs, or even scrub off barnacles, while in the water. Unless the ocean is absolutely dead calm (i.e. almost never), the boat is wallowing around, and could possibly hit you on the head and knock you out. You’re trying not to think too much about what wildlife could be below you, wondering whether to take an exploratory nibble to see if you taste good. You’re also trying to ignore that fact that the ocean is around two miles deep on average, which can be a bit of a freaky thought.

I am guessing that, most likely, Angela grew exhausted and didn’t have the strength to pull herself back on board. Unlike me, she was smart enough to stay tethered to the boat, so she didn’t become separated from it, but maybe her limbs weren’t strong enough to pull herself up and onto the deck. I used to get back on board by placing a foot in the grab-line, and then using the horizontally-stowed oars as climbing bars to pull myself up. I needed the full use of all arms and legs to get safely back into the boat.

Whatever actually happened, it seems it’s the way she would have wanted to go. Angela’s wife, Debra, says that, “Angela was living her dream. She loved being on the water as you could see from the photos she sent.”

Filmmaker Soraya said, “This was a clear risk going in since day one, and Angela was aware of that more than anyone else. She was willing to die at sea doing the thing she loved most.”

So I hope that her last moments were peaceful, a calm release of her soul into the deep blue waters of the Pacific. My sympathies are with Debra, and all who knew and loved her.

With Angela in January, 2009

With Angela in January, 2009I don’t claim to have known Angela well. We met only a few times. But she was a great inspiration to me as an indomitable woman to lived life to the fullest. Her brothers told her she wouldn’t make it in the military – she proved them wrong. A sporting injury was compounded by failed surgery – she went on to become a medal-winning Paralympic athlete. She lost her job, her marriage, and ended up living on the streets – she bounced back and created a rowing programme for people with disabilities. She came out as gay – she married Deb and became a vocal LGBTQ activist. She was a legend.

I was surprised how much the news of her death affected me. My personal belief is that death is not necessarily traumatic (see my interview with Sue Brayne in The Gifts of Solitude, which has informed my view of what happens when we pass over), and that it is not necessarily the final end. Maybe Angela had done all she came here to do in this lifetime – to be sure, she did a lot. So maybe it was a more selfish sadness that I was feeling, that her light is no longer here to shine on this earthly plane – except that it is still shining, for as long as we remember Angela and her courageous spirit.

(Angela’s story is told in her book, Rowing Against the Wind.)

Other Stuff:

Lia Ditton has recently set out to also row to Hawaii, starting from San Francisco. She is hoping to beat my time, which shouldn’t be too hard if conditions are favourable. I was built for style, not speed.

June 18, 2020

Team of Teams

A book on military strategy may not seem like an obvious place to find a model for the future of humanity, but I found Team of Teams tremendously inspiring in terms of the world we could create.

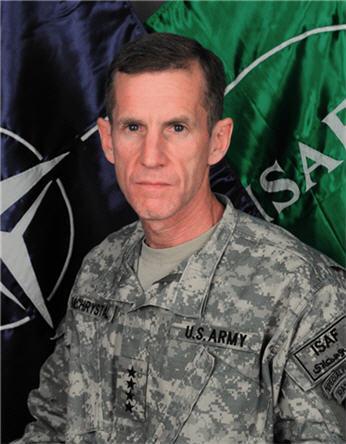

When General Stanley McChrystal arrived in Iraq in 2003 as the newly appointed commander of the Joint Special Operations Task Force, he found that al-Qaeda were running circles around the task force, despite being massively outgunned in terms of numbers, equipment, and training. To put it in biblical/American terms, the Davids were whipping Goliath’s ass. This realisation led to a radical restructuring of the way the task force operated, in order to become more nimble and responsive to fast-evolving situations in real time.

Stan McChrystal

Stan McChrystalThe story told in Team of Teams makes an interesting complement to two other books I have read recently – Coping With Chaos and Finding Our Way (which I reviewed in this blog), and one that I read a while ago, Reinventing Organisations.

Coming from very different directions, all these books arrive at the same conclusion: in this increasingly complex (versus merely complicated) world, hierarchical power structures simply don’t work any more. No single human brain can cope with the sheer amount of data that is available, nor the “wickedness” of our challenges – with “wicked” referring to a problem that has multiple causes, multiple solutions, involves multiple stakeholders, and is constantly evolving, so is never truly “solved”.

[See also the sidebar on the 10 features of wicked problems in the Harvard Business Review, and my blog post on Wicked and Wise, by Alan Watkins and Ken Wilber.]

If you still hold a mental model of the military world as being based on hierarchy, command-and-control dynamics, and blind obedience to orders, you may be surprised to find Team of Teams uses phrases like emergence, shared consciousness, trust, common purpose, and empowered execution. Like many organisations facing unprecedented situations, the Task Force found it needed to decentralise authority and decision-making in order to overcome a scrappy but highly motivated terrorist network. It needed to stop behaving like an org chart and start behaving like a single organism, sharing information freely across what had once been siloed units. It had to sacrifice MECE (mutually exclusive, collectively exhaustive) efficiency in favour of messy effectiveness.

I find myself fascinated by this new modus. It seems clear to me that this is the direction we are heading, and that it is a good thing. Top-down hierarchies may have worked in the simpler world of the nineteenth or even twentieth centuries, but the pace of change and the volume of available data have increased exponentially. The COVID crisis caught many governments flat-footed, especially those of the larger nations, with the result that smaller, more localised authorities (city mayors, state governments etc) responded more quickly and assumed more power. More organisations are going “teal” (see Reinventing Organisations and/or check out this lecture by its author, Frederic Laloux), devolving authority to small, self-organising teams.

As Margaret Wheatley puts it in Finding Our Way:

[Self-organising systems] “have the capacity to create for themselves the aspects of organisation that we thought leaders had to provide. Self-organising systems create structures and pathways, networks of communication, values and meaning, behaviours and norms. In essence, they do for themselves most of what we believed we had to do for them.”

The future may be here, but it is not yet evenly distributed. There are still many systems where information flows don’t provide essential feedback to sub-units on a timely basis, or at all.

For example, the systemic failures that led to the 2008 sub-prime mortgage fiasco and the resulting global financial crisis have not yet been resolved, because the feedback loops didn’t work. Governments bailed out the banks, and the perpetrators of the crisis still took home outsized bonuses. They received no meaningful feedback that their strategies had failed, and worse still, had caused massive hardship for many people. They didn’t see that hardship, so it wasn’t real to them. There is every danger they would do the same thing again.

Another example would be climate change, in which all of us in the developed world are perpetrators. But mostly the consequences of our choices are hidden from us. We don’t see forests being cleared to make way for cattle. We don’t see the lengthy supply chains that bring us food and products. We don’t see the methane emitted by the food we toss into landfill. And most of us don’t see the melting Arctic, or the sea level rise affecting small island nations. Again, we lack meaningful feedback that might motivate us to make different choices.

In the Joint Operations Centre at their bunker at Balad, McChrystal’s task force could see on an array of screens what was happening all across the region in real time. Daily O&I (Operations and Intelligence) briefings lasted an hour and a half, and were mandatory for the seven thousand personnel across the region, enabling them to share crucial information and best practice.

What would it be like if we had a similar command centre for our world, or even for our own individual world? What would it be like if we had trustworthy, unfiltered, real-time information about the consequences of our actions, individually and collectively, against key metrics? For many people, their key metric of success is how many “likes” they just got on Facebook or Instagram, but what could the world be like if we had access to real-time metrics that actually mattered? What if ignorance could no longer be an excuse?

What would it be like if we had a similar command centre for our world, or even for our own individual world? What would it be like if we had trustworthy, unfiltered, real-time information about the consequences of our actions, individually and collectively, against key metrics? For many people, their key metric of success is how many “likes” they just got on Facebook or Instagram, but what could the world be like if we had access to real-time metrics that actually mattered? What if ignorance could no longer be an excuse?

And what would it be like if we were able to truly embrace the power of the internet to create a world in which humanity could respond like a unified organism, with shared consciousness and emergent intelligence?

Ah, but then we would have to have a shared concept of what “success” looks like to us. It is more straightforward in a military context. There is an “enemy” who must be overcome, disrupted, disempowered, killed. Success can be measured in terms of strikes, captives, key figures removed or neutralised. But as humanity, we haven’t really decided what we are optimising for.

What would be the chief criterion against which we would evaluate the success or failure of the human enterprise? Our longevity as a species? Our sum total of wellbeing and happiness? The love and bonds of trust we generate? Or… a race to see which one of us can acquire the most toys before he (on current models of success, it would be 99% likely to be a “he”) dies?

Our ideal course would be simple, but not easy.

Decide what we are trying to achieve.

Decide what metric best suits the goal.

Measure it, and share it with every human to create a virtuous feedback loop of motivation and reward towards our shared objective.

Can we do it? Can humanity unite around a common purpose, and become a team of teams?

[Full disclosure: I know Stan McChrystal slightly – we are both Senior Fellows at Yale’s Jackson Institute, and have also crossed paths at the Renaissance Weekend conference in the US – but our personal acquaintance has not coloured my perspective on his book, which I genuinely endorse as a valuable text for anybody interested in leadership for the 21st century.]

Other Stuff:

I have been granted the license to run TEDxStroudWomen on 29th November, which we are hopeful can take place as a normal TEDx with a live audience. We are inviting aspiring speakers to apply via our website. You don’t have to live in Stroud, nor be a woman, to speak, but you will need to go through our selection process – details here. Our theme, very much in keeping with shared consciousness, is “emergence”. Please note that we will be running a series of fortnightly workshops to prepare our speakers, meaning that you should be within a commutable radius of Stroud, UK. If you have aspirations to be a TEDx speaker, please do apply, and/or forward this to someone you know who you think would be a great fit for our theme.

I have been granted the license to run TEDxStroudWomen on 29th November, which we are hopeful can take place as a normal TEDx with a live audience. We are inviting aspiring speakers to apply via our website. You don’t have to live in Stroud, nor be a woman, to speak, but you will need to go through our selection process – details here. Our theme, very much in keeping with shared consciousness, is “emergence”. Please note that we will be running a series of fortnightly workshops to prepare our speakers, meaning that you should be within a commutable radius of Stroud, UK. If you have aspirations to be a TEDx speaker, please do apply, and/or forward this to someone you know who you think would be a great fit for our theme.

June 11, 2020

Decommodify Power

commodification

noun, often disapproving

the fact that something is treated or considered as a commodity (= a product that can be bought and sold)

This article about defunding the police in the US got me thinking about the relationship between money and power.

The point of the article is summed up in this paragraph:

“…the United States has an extreme budget commitment to prisons, guns, warplanes, armored vehicles, detention facilities, courts, jails, drones, and patrols — to law and order, meted out discriminately. It has an equally extreme budget commitment to food support, aid for teenage parents, help for the homeless, child care for working families, safe housing, and so on. It feeds the former and starves the latter.”

It advocates for moving investment upstream, so rather than throwing money at dealing with the consequences of inequity, simply reduce the inequity:

“It would mean ending mass incarceration, cash bail, fines-and-fees policing, the war on drugs, and police militarization, as well as getting cops out of schools. It would also mean funding housing-first programs, creating subsidized jobs for the formerly incarcerated, and expanding initiatives to have mental-health professionals and social workers respond to emergency calls.”

In other words, to de-power the police, and empower deprived communities, reallocate the money from the former to the latter.

Almost always, money and power go together. “Rich and powerful” is almost a tautology. In the US, the relationship is particularly blatant. There is a strong correlation (although not necessarily causation) between campaign funding and the chances of victory.

Built into the system of money and power is a feedback loop that over time generates a bigger and bigger divide between those who benefit from the system, and those who don’t. An (apparently controversial, although also self-evident) new book by Daniel Markovits, The Meritocracy Trap, states:

“Whatever its original purposes and early triumphs, meritocracy now concentrates advantage and sustains toxic inequalities. And the taproot of all these troubles is not too little but rather too much meritocracy. Merit itself has become a counterfeit virtue, a false idol. And meritocracy – formerly benevolent and just – has become what it was intended to combat. A mechanism for the concentration and dynastic transmission of wealth and privilege across generations. A caste order that breeds rancor and division. A new aristocracy, even.”

The core of the problem is that those who have benefited from meritocracy naturally want their children, too, to benefit from meritocracy. So they:

“invest thousands of hours and millions of dollars to get elite educations for their children. And meritocratic jobs require elite adults to work with grinding intensity, ruthlessly exploiting their educations in order to extract a return from these investments.”

Meritocracy becomes less a ladder, more a treadmill for the elite, while systematically excluding the non-elite whose parents had less time and less money to invest in their education. At all levels, people get trapped where they are, and nobody is particularly happy about it.

In The Spirit Level, by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson, the authors provide evidence that almost everything – from life expectancy to mental illness, violence to illiteracy – is affected not by how wealthy a society is, but how equal it is, and that societies with a bigger gap between rich and poor are bad for everyone in them – including the well-off.

And yet, change is hard due to the status quo bias that is built in. Those in power won’t change the system because it is the very system that has put them into power.

In last week’s blog post, I referred to the theory of point attractors in a complex adaptive system such as human society: change to a complex system requires two complementary actions:

Random shocks must be introduced into the existing regime

A seed for the new order must be created outside the existing regime

Buckminster Fuller put it another way:

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

So what could that look like? Given its self-perpetuating nature, how do we disrupt the status quo?

I’m sure there are many possible solutions. Personally, I’m pursuing my interest in complementary currencies. If you create a parallel economic system – possibly one that rewards the prosocial behaviours, like collaboration, caring, sharing, and contribution, but it doesn’t have to be, so long as it’s a separate system from the mainstream – you don’t have to try and take away the toys from the rich folks, because they’ll never give them up. You just create another system that enables its participants to get what they want, without reference to the existing system. Over time, more and more people will be attracted to the new system, for the obvious reason that it is to their benefit.

Money is, essentially, a game. To misappropriate Einstein’s quote about reality, money “is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one”. It works because we have all bought into the story of money, and agreed that its supply is controlled by the government, via the banks. And right now, the national currency is generally the only game in town.

But what if we set up another game? What if we formed an agreement that we could use acorns, or seashells, or points in an app, to enable trade with other people who had signed up to the same agreement?

If enough individuals and businesses signed on for the new, fairer economy, and departed the old, rigged system, the lockstep link between (conventional) money and power would be weakened, and we might have a chance at an equitable balance.

Radical? Probably.

Realistic? Only one way to find out.

Other Stuff:

An informative, insightful, and ultimately optimistic article that I recommend: Why Ta-Nehisi Coates is hopeful, in conversation with Ezra Klein for Vox.

June 4, 2020

Fairness, Floyd, Cooper, Cummings, and Chaos

I’m extremely nervous about mentioning what’s currently happening in the US, being neither American nor black, and thus almost certain to say something wrong. There again, I can’t not mention it, as it’s so hugely important. So I’ll do my best, and please forgive me if I say anything ignorant and/or offensive.

Trevor Noah’s commentary on George Floyd’s murder by police officer Derek Chauvin strikes me as brilliant and insightful: he says that the social contract that enables societies to function was broken, and is broken every day for black people all across America (and in many other countries). He says that the looting of Target is retaliation (and mild retaliation at that) for the metaphorical looting of black people’s bodies by police officers, vigilantes (Ahmaud Arbery), and privileged people like Amy Cooper who weaponise their whiteness, knowing they can use the colour of a person’s skin as a presumption of guilt, and that they can count on the police to be their allies.

Trust is a central plank of the social contract. We trust that everybody will generally observe the rules of a civilised society so that we can all live in harmony. We accept some limitations on our freedom to do what we damn well please, in the faith that everybody else is likewise accepting the same limitations, for the benefit of all.

Generally, when one person ruptures that pact, society calls them a criminal, and punishes them. The greater good requires that there are sanctions against breaking faith with the social contract.

So what happens when the person who creates the rupture is a police officer? (or a president?) When a man whose mantra is supposed to be to protect and serve, kills in cold blood one of the people he is supposed to be protecting and serving?

And the tragic Floyd/Chauvin story is far from exceptional.

According to The Atlantic, “Of the 1,146 and 1,092 victims of police violence in 2015 and 2016, respectively, the authors found that 52 percent were white, 26 percent were black, and 17 percent were Hispanic”, but only 13.4% of the US population is black, so the proportion of victims is around twice what it “should” be. According to several different studies, black men aged 15 to 34 are between nine and 16 times more likely to be killed by police than other people.

And the deaths are only the tip of a much bigger iceberg of over-policing, harassment, and disproportionate incarceration. To many, especially people of colour, “American justice system” seems like an oxymoron.

The outrage that greeted the news that Dominic Cummings, a senior adviser to Boris Johnson, had broken the lockdown guidelines that he helped to draft, may seem disproportionate, but there are some parallels. When people have made personal and economic sacrifices for the common good, and one person – especially a person in authority – acts as if they are above the law, the moral indignation is visceral.

As in any relationship, once trust has been lost, it is very hard to win back, and when trust has been lost in the key institutions of a country – its judiciary, police force, media, and/or government – then little stands in the way of anarchy.

I don’t want to end on a negative note, so I will do my best to offer a pointer as to what needs to happen, not just in the US, but anywhere that injustice and inequality threaten. According to chaos theory, a change to a complex system requires two complementary actions:

Random shocks must be introduced into the existing regime. Yes, we have these, aplenty.

A seed for the new order must be created outside the existing regime. Hmmm….

But I do believe those seeds exist. There are communities and groups finding new ways of living. But are those seeds strong enough? Will they fall on fertile soil? Will enough of them germinate? Only time will tell.

Other Stuff:

The Biggest Little Farm

Speaking of fertile soil, if you are in need of upliftment, I highly recommend The Biggest Little Farm, a gorgeous film about a couple who take on two hundred acres of barren earth outside LA and turn it into a regenerative farm. John Chester was a wildlife film cameraman in his previous life, so the shots of animals are just beautiful. You can go deeper with the Chesters on the Rich Roll interview.

Here’s a question for you. The Biggest Little Farm is a perfect example of a complex system, in which everything is interconnected. Are there any lessons we can take away from it to help inform the changes that need to happen in our human complex systems?

CogX

I’ve got 10 free passes to CogX (June 8th-10th), featuring Jane Goodall and Samantha Power, amongst others, on the theme of “How do we get the next 10 years right?” First come, first served. To claim your free pass, follow this link.

Interview

I’d also like to point you in the direction of an interview I did pre-COVID with my friend, Sue Brayne, who I in turn interviewed for my latest book, The Gifts of Solitude. She generously implies that I had some inkling that a major disruption was coming. Well, I did, but that was fairly obvious to me – I just didn’t know what, and when. If my crystal ball was as accurate as Sue suggests, I would do a lot better on the stock market!

Audiobooks

I’m currently recording the audiobook of The Gifts of Solitude, hampered by the fact that professional sound recording studios are still closed. Living in the countryside as I do, I have to wait for all the birds to go to sleep before I can start recording, which around this latitude is getting on for 10pm, and I am so very much not a night owl. If you know anybody in or around Gloucestershire who has a private recording studio, please let me know!

I’d also like to remind you that my previous two books are available on Audible, narrated by yours truly. So if you enjoy listening to my dulcet tones, check out Rowing the Atlantic and Stop Drifting Start Rowing.