Roz Savage's Blog, page 12

October 15, 2020

A Brain of Two Halves

“If I am right, that the story of the Western world is one of increasing left hemisphere domination, we would not expect insight to be the key note. Instead, we would expect a sort of insouciant optimism, the sleepwalker whistling a happy tune as he ambles towards the abyss.” – Iain McGilchrist

In case you’re not familiar with the footballing phrase, “a game of two halves”, it has become a cliché in British soccer commentary, and means games which have a different character in the two halves. The same could be said of our brains.

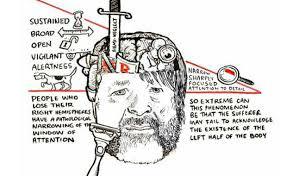

The human brain, and the brains of most other animals, is made up of two hemispheres: the left hemisphere is good at linear and reductionist thinking, categorisation, logic and analysis, mechanical concepts, and tasks requiring focused attention. It is optimistic, individualistic, has the monopoly on verbal language, and is blessed with an extremely robust perception of its own abilities (remind you of anybody you know?!).

The right hemisphere is in many ways the converse, the yin to the left hemisphere’s yang. It is good at conceptual and holistic thinking, imagination, intuition, compassion, prefers the organic to the mechanical, and has a wider orbit of peripheral vision, metaphorically speaking. It is the seat of most emotions, apart from anger – only the left hemisphere does anger. It has no verbal language, and has a high tolerance for paradox, and tends to be pessimistic, melancholy and doubtful (you may know people like this too…).

According to the philosopher and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, author of The Master and His Emissary, our world is becoming increasingly left-brain dominant, and this is not a good thing.

According to the philosopher and psychiatrist Iain McGilchrist, author of The Master and His Emissary, our world is becoming increasingly left-brain dominant, and this is not a good thing.

(Full disclosure: Iain is a dear friend of mine, and I would like to emphasise that any liberties and/or errors I have introduced in interpreting his work are mine, not his).

Our best theory at the moment is that the two hemispheres were a positive evolutionary adaptation that allowed us to maintain tight focus on the task at hand (like eating our lunch) while also being aware of what was going on around us (thereby not becoming some other creature’s lunch).

Ideally, the two hemispheres operate in harmony, each playing to its strengths. But here we run into a snag, which inspires the title of McGilchrist’s book. The story goes that there was once a wise and spiritual master who had a small but prosperous domain, but as his subjects grew in number, he trained a number of trusted emissaries to oversee the welfare of its far-flung outposts. In his wisdom, he chose not to micro-manage his emissaries, but to respect their autonomy. Unfortunately, his most ambitious emissary began to abuse his power in order to further his own wealth and influence. “And so it came about that the master was usurped, the people were duped, the domain became a tyranny; and eventually it collapsed in ruins.”

Following this metaphor, the right hemisphere should ideally be the chief strategist, given its wider and wiser perspective, while the left hemisphere plays to its strengths as administrator and executive. As McGilchrist writes, “the purpose of the left hemisphere is to allow us to manipulate the world, not to understand it”.

The dynamic between the two hemispheres is reminiscent of the creative tension between yin and yang, which gives rise to the life force, or qi:

“Another way of thinking of the difference between the hemispheres is to see the left hemisphere’s world as tending towards fixity, whereas that of the right tends towards flow. All systems in nature, from particles to the greater universe, from the world of cellular processes to that of all living things, depend on a necessary balance of the forces for stasis with the forces for flow. All existing things could be thought of as the product of this fruitful tension.”

So the hemispheres should ideally be a complementary double-act, and it seems likely that this used to be the case, or at least, more so than it is now. However, given its ebullient self-confidence, the left hemisphere has gradually usurped the power of the right. The right hemisphere knows that it needs the left. The left has forgotten that the right exists. (Any resemblance to patriarchy is purely coincidental – or not.)

According to McGilchrist, we see the symptoms of the dominant left-brain worldview all around us. This shift becomes a positively reinforcing feedback loop, as the left hemisphere creates an external world in its own image:

“Here I suggest that it is as if the left hemisphere, which creates a sort of self-reflexive virtual world, has blocked off the available exits, the ways out of the hall of mirrors, into a reality which the right hemisphere could enable us to understand. In the past, this tendency was counterbalanced by forces from outside the enclosed system of the self-conscious mind; apart from the history incarnated in our culture, and the natural world itself, from both of which we are increasingly alienated, these were principally the embodied nature of our existence, the arts and religion. In our time each of these has been subverted and the routes of escape from the virtual world have been closed off. An increasingly mechanistic, fragmented, decontextualised world, marked by unwarranted optimism mixed with paranoia and a feeling of emptiness, has come about, reflecting, I believe, the unopposed action of a dysfunctional left hemisphere.”

It’s possible that we used to have more of an intuitive sense of the underlying nature of reality (see my blog about Don Hoffman’s work for more about this), but the reductionist, materialist worldview of the left hemisphere is increasingly blocking out our ability to perceive the invisible realms that exist beyond our senses.

It’s possible that we used to have more of an intuitive sense of the underlying nature of reality (see my blog about Don Hoffman’s work for more about this), but the reductionist, materialist worldview of the left hemisphere is increasingly blocking out our ability to perceive the invisible realms that exist beyond our senses.

It was this reductionist, materialist thinking that reduced the number of our “official” senses to a mere five. It has been suggested Aristotle’s De Anima was the start of the idea that there had to be an observable physical organ corresponding to a sense for it to be real, rather than imaginary or “extrasensory” perception – eyes for sight, a nose for smell, and so on. Individuals (usually women) who exhibited allegedly extrasensory abilities, such as the ability to communicate with plants for medicinal purposes, have for the last several millennia been denigrated as witches, persecuted, and killed, leading to the loss of their wisdom traditions and (possibly) inheritable capabilities.

The more that our left hemisphere enforces its (literally) narrow-minded worldview, the more we cut ourselves off the useful information being processed by the right hemisphere. According to McGilchrist, we have paid dearly for our increasingly left-hemisphere orientation:

“We know so much, we can make so much happen, and we certainly invest much in the attempt to control our destinies. And yet, if we are honest, we feel as though it ought somehow to have added up to – more than this. Meanwhile, around us we can scarcely fail to see the evident global degradation and destruction of what we now call ‘the environment’, but which is nothing less than the living world; the breaking up of complex, close-knit communities, and their ways of living in harmony with nature, that took at least centuries, if not millennia, to form; the substitution of a way of life that we have already determined in the West to be lacking in meaning, often aesthetically barren, driven by commercialism and morally bankrupt, devoted to the pursuit of pleasure and happiness, but delivering anxiety and systemic dissatisfaction; the erosion, and in some cases the trashing, of ancient artistic and spiritual traditions; and the loss of the sense of uniqueness as everything becomes abstracted, generalised, categorised, mechanised, represented and rendered merely virtual… Meaning emerges from engagement with the world, not from abstract contemplation of it.”

Not just individuals or societies, but entire empires have also paid dearly for our abstraction from the natural world. McGilchrist sees, in accounts of the fall of the Greek and Roman empires, evidence of increasing left hemisphere dominance:

“But [the flourishing] did not last. It may be that an increasing bureaucracy, totalitarianism and an emphasis on the mechanistic in the late Roman period represents an attempt by the left hemisphere to ‘go it alone’.”

(Ringing any bells? For more on the collapse of empires, see this earlier blog post.)

If you need cheering up after McGilchrist’s rather bleak prognosis, I recommend Jill Bolte Taylor, who suffered a catastrophic left hemisphere stroke at the age of 37 (which might not sound very cheering – but it gets better).

Bolte Taylor was a neuroanatomist so, given her professional expertise, she was able to observe, with (mostly) dispassionate calmness, her life-threatening predicament in real time as she had her stroke, which she describes in her 2008 TED Talk and book, My Stroke of Insight. As the blood wreaked havoc in her left hemisphere, shutting down its functions, she found herself seeing reality in an entirely different way which, far from being terrifying, was extremely alluring, even spiritual:

Bolte Taylor was a neuroanatomist so, given her professional expertise, she was able to observe, with (mostly) dispassionate calmness, her life-threatening predicament in real time as she had her stroke, which she describes in her 2008 TED Talk and book, My Stroke of Insight. As the blood wreaked havoc in her left hemisphere, shutting down its functions, she found herself seeing reality in an entirely different way which, far from being terrifying, was extremely alluring, even spiritual:

“As the haemorrhaging blood interrupted the normal functioning of my left mind, my perception was released from its attachment to categorization and detail. As the dominating fibres of my left hemisphere shut down, they no longer inhibited my right hemisphere, and my perception was free to shift such that my consciousness could embody the tranquillity of my right mind. Swathed in an enfolding sense of liberation and transformation, the essence of my consciousness shifted into a state that felt amazingly similar to my experience in Thetaville. I’m no authority, but I think the Buddhists would say I entered the mode of existence they call Nirvana… In the absence of my left hemisphere’s analytical judgment, I was completely entranced by the feelings of tranquillity, safety, blessedness, euphoria, and omniscience.”

She uses phrases that could equally be used by someone describing a peak spiritual experience, or the effects of hallucinogenic drugs, such as “peaceful bliss of my divine right mind”, “glorious bliss”, and “sweet tranquillity”.

“My left hemisphere had been trained to perceive myself as a solid, separate from others. Now, released from that restrictive circuitry, my right hemisphere relished in its attachment to the eternal flow. I was no longer isolated and alone. My soul was as big as the universe and frolicked with glee in a boundless sea.”

Bolte Taylor equates the left hemisphere with head, thinking, mind consciousness, small ego mind, small self, masculine, and yang consciousness, and the right with heart, feeling, body’s instinctive consciousness, capital ego mind, inner or authentic self, feminine, and yin consciousness.

I’m not for a moment here suggesting that we would be better off without our left hemisphere – it evolved for a very good reason, and we wouldn’t do very well without it – but I invite you to imagine what it might be like if we were able to subdue the left hemisphere at will, and connect intentionally with the worldview of the right hemisphere. Or we can simply learn from Bolte Taylor’s account:

“My stroke of insight is that at the core of my right hemisphere consciousness is a character that is directly connected to my feeling of deep inner peace. It is completely committed to the expression of peace, love, joy, and compassion in the world… It is my goal to help you find a hemispheric home for each of your characters so that we can honour their identities and perhaps have more say in how we want to be in the world. By recognizing who is who inside our cranium, we can take a more balanced-brain approach to how we lead our lives.”

Seems to me that Bolte Taylor is agreeing with McGilchrist that both an individual and a society function optimally when it knows when best to invoke right brain consciousness, and when to rely on the left. A quote usually attributed to Albert Einstein (who, according to a 2013 study, was blessed with an unusual corpus callosum that had more extensive connections between certain parts of his cerebral hemispheres compared to the brains of both younger and older control groups) states:

Bolte Taylor feels that most of us (with exceptions in indigenous cultures, and assorted individuals in the western world who may practice as healers, intuitives, and so on) will have to work mindfully (literally) to reverse the shift and re-create balance in our predominantly left-brain-oriented world.

We would do well to remember who is the master, and who is the emissary, which is the sacred gift and which is the servant, and do our best to nurture the optimal balance between the two.

Note: The Master and His Emissary is a fascinating, but somewhat daunting, read – and I’m not easily daunted. There is a relatively bite-sized version called The Divided Brain and the Search for Meaning, also by Iain, and also very good, and I particularly recommend this animated/illustrated RSA talk.

Other Stuff:

Early bird tickets for TEDxStroudWomen are selling fast – but luckily, as we’ve now had to go virtual, the sky is the limit, and the more the merrier! Please join us on Sunday 29th November for a day of fascinating talks around our theme of Emergence. All details on Eventbrite and on our website.

Early bird tickets for TEDxStroudWomen are selling fast – but luckily, as we’ve now had to go virtual, the sky is the limit, and the more the merrier! Please join us on Sunday 29th November for a day of fascinating talks around our theme of Emergence. All details on Eventbrite and on our website.

October 8, 2020

The Taoist Farmer

In this craziest of years, here is a story that I hope will be balm to some troubled souls, maybe especially on the far side of the pond, given RBG, ACB, DJT, and COVID.

There was once a farmer in ancient China who owned a horse. “You are so lucky!” his neighbours told him, “to have a horse to pull the cart for you.” “Maybe,” the farmer replied.

One day he didn’t latch the gate properly and the horse ran off. “Oh no! This is terrible news!” his neighbours cried. “Such terrible misfortune!” “Maybe,” the farmer replied.

A few days later the horse returned, bringing with it six wild horses. “How fantastic! You are so lucky,” his neighbours told him. “Now you are rich!” “Maybe,” the farmer replied.

The following week the farmer’s son was breaking-in one of the wild horses when it kicked out and broke his leg. “Oh no!” the neighbours cried, “such bad luck, all over again!” “Maybe,” the farmer replied.

The next day soldiers came and took away all the young men to fight in the war. The farmer’s son was left behind. “You are so lucky!” his neighbours cried. “Maybe,” the farmer replied.

(Story of the Taoist Farmer, told by Alan Watts, the British writer and teacher known for interpreting and popularising Buddhism, Taoism, and Hinduism for a Western audience. I’ve just finished listening to the audiobook of The Book: On the Taboo Against Knowing Who You Are, which I highly recommend. It’s jam-packed with timeless wisdom, and a few smiles along the way too.)

We never know how things are going to turn out. Have you ever had an experience when something went terribly wrong – you missed your flight, you lost your bag, your car broke down – but somehow that disaster led to something really good happening, some synchronicity or serendipity that couldn’t have happened otherwise?

So if you’ve been on an emotional rollercoaster recently, have patience.

There’s another anecdote that turns out not to be true, but let’s not let the facts get in the way of a good story.

The story goes that Zhou Enlai, the premier of Communist China from 1949-1976, was once asked for his impressions of the long-term effects of the French Revolution (in 1789). Zhou famously responded that it was “too soon to tell”.

So, here’s to more “maybe”. Let’s take an attitude of “too soon to tell”.

It all works out in the end, and if it hasn’t worked out, it isn’t the end yet…

TEDxStroudWomen:

6 weeks to go until TEDxStroudWomen on 29th November, which I’m curating, and early bird tickets are now on sale! Due to COVID, we will be virtual and livestreaming from the Sub Rooms in Stroud. Nine amazing speakers, presenting leading edge ideas on economics, health, compassion, community, education, collaboration, art, and sustainability. Tickets just £5 until the end of October, and you can join us from anywhere in the world! We start at 2pm UK time, 9am EST, 6am PST – hope to “see” you there!

We are also looking for sponsorship. All donations are welcome – no contribution too small. So even if you want to support Stroud women, and women in general, but can’t attend on the day, you could buy a ticket anyway to make a micro-donation, and/or spread the word to your network.

Or, if you would like to make a bigger contribution – first of all, THANK YOU! And second, please email me at [email protected].

Thanks in advance for any support you can give us – all very much appreciated!

October 1, 2020

Complexity, Emergence and Creativity

I’ve been thinking about emergence a lot recently. It’s the theme of the event that I’m curating, TEDxStroudWomen (which is now going to be virtual and livestreamed, so you can attend, no matter where in the world you are – tickets now on sale here!), and is also, I absolutely believe, going to be essential to the shift in consciousness that we need if we’re going to do anything more than dabble around the edges of our current existential crisis.

Emergence, in this sense, is a feature of a complex system, which in turn is defined as a system comprising many distinct elements that interact with each other, for example: financial markets, cities, and natural ecosystems such as forests and oceans. I am particularly interested in the subset of complex systems known as complex adaptive systems, which Wikipedia defines as:

“…a system in which a perfect understanding of the individual parts does not automatically convey a perfect understanding of the whole system’s behaviour. In complex adaptive systems, the whole is more complex than its parts, and more complicated and meaningful than the aggregate of its parts.”

Emergence refers to this particular aspect of complex adaptive systems (other features would be diverse agents and phase transitions, which I might write about in the future).

Fittingly, water is a good example. It is made up of oxygen and hydrogen, which are both gases at room temperature, but they come together to create H2O, a liquid. In a further step of emergence, six or more molecules of water create “wetness”, a property that a single water molecule does not possess (even apart from the fact that it would be really, really hard to pick up a single water molecule to decide whether it was wet or not).

As Daniel Schmachtenberger, of Civilization Emerging, says in his talk on emergence (which is absolutely brilliant, and I highly recommend it):

“How do you bring particles or planets or anything together and all of a sudden the whole has some properties that none of the parts have? Like, where do they come from? Which is why in the fields of science that study emergence, which evolutionary theory, and biology, and systems science, and complexity theory studies, it’s considered the closest thing to magic that’s actually a scientifically admissible term.”

We all have some personal connection to emergence. Some researchers believe that consciousness is an emergent property of complex brains (although Donald Hoffman disagrees), so if they are right, the sense that I have of my self-ness is an example of emergence that goes to the very core of my existence as a sentient (mostly) being.

As another example, many of us will have had the experience of mulling on a question over an extended period of time, eventually giving rise to a sudden “a-ha” moment. Neuroscientists have started to explore the neural correlates of insights (although again, Hoffman might dispute that correlation equals causation), which occur in the right hemisphere of the brain.

I have my own version of what goes on. I think that, as we acquire data to inform our response to a question, we build up a web of knowledge that gets encoded into our neural network. Eventually this network spontaneously gives rise to a sudden insight, often when we are thinking about something completely different (or not thinking about anything much at all). The sense of surprise that usually accompanies such an insight suggests that the whole (the insight) is greater than the sum of the parts (the data we have been acquiring).

This was certainly my experience when the idea came to me to row across oceans, and use my adventures to raise awareness of environmental issues. I had been pondering for about six months what I could do to support the environmental cause, during which time I had been reading, thinking, and conversing in relation to my quest, and also in areas that had seemed unrelated but which had helped create the ground from which this idea emerged. When the a-ha moment came, during a long drive with my brain in neutral, the idea was astonishing and yet also perfect, meeting all my criteria and more besides.

So now I deliberately cultivate such insights. I picture the gathering of information as if I am putting ingredients into the melting pot of my subconscious mind, where I leave them to bubble until they alchemize into something new, exciting, and unpredictable (albeit rarely on cue). I also allow generous mental down-time, to allow space for the idea to emerge. As I discovered on the ocean, when there is too much information pouring into the mind, there is no way for ideas to come out, so this disengagement from input is an essential part of the process. The hypnopompic period just as I am waking up is especially fruitful; there is a precious window of opportunity before my conscious mind has fully engaged, as it tends to drown out the more creative subconscious.

In Synchronicity, Joseph Jaworski describes how such moments can also arise in a group:

“C. G. Jung’s classic, ‘Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle’, defines synchronicity as ‘a meaningfulcoincidence of two or more events, where something other than the probability of chance is involved’. In the beautiful flow of these moments, it seems as if we are being helped by hidden hands… Over the years my curiosity has grown, particularly about how these experiences occur collectively within a group or team of people. I have come to see this as the most subtle territory of leadership, creating the conditions for ‘predictable miracles.’

”

Otto Scharmer and Katrin Kaufer also refer to this process of flow in the brilliant Leading From The Emerging Future, which describes presencing process:

“Presencing is a blended word combining sensing (feeling the future possibility) and presence (the state of being in the present moment). It means sensing and actualizing one’s highest future possibility—acting from the presence of what is wanting to emerge.”

You might have your own opinion about creativity and where it comes from – from the collective unconscious, intuition, the right hemisphere, the muse, the Universe, God? The main thing I want to say is that my own creativity works best when I know it’s not coming from me. The thinking brain definitely has its uses, and I’m glad I have one. Daily logistics would be really challenging without it. But when it comes to the big, important stuff, I really do my best to get out of the way, and let what wants to emerge, emerge.

The ideas that come from that rather mysterious realm are far better than mine.

September 24, 2020

Reality, Russian Dolls, Rocks and Ripples

I’ve written before about Don Hoffman’s book, The Case Against Reality, and you might want to read that blog post first if you haven’t already – especially if what I write below strikes you as completely bonkers. At the moment it’s an unproven theory, but for me it resonates with other reading I’ve done, in both the psychological and spiritual realms, and if true, it opens up all kinds of exciting possibilities for societal transformation.

In his book, The Case Against Reality: How Evolution Hid The Truth From Our Eyes, Donald Hoffman, a quantitative psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, sets out a radical new theory of reality, based primarily on evolutionary biology and backed up with mathematics. I will offer a short and necessarily crude summary of his theories, and then focus on the aspects that I find the most fascinating, and explain why.

This theory does great violence to most people’s intuitions about what is objectively real and what is not, but I invite you to suspend disbelief and consider that it just might be true, and if so, whether it could start to reconcile science and spirituality. I have a mental picture of science and spirituality divorcing each other around the time of Galileo and the Age of Enlightenment in the 17th century, and it just might be that after several hundred years of estrangement, they are now starting to once again flirt with each other. If Hoffman and his colleagues are right, we may in our lifetimes see them consummate their reunion.

He proposes that over the course of millions of years, evolution has favoured organisms that perceive reality in a useful way, rather than an accurate way. Computer simulations have proved repeatedly that, other things being equal, an organism maximises its evolutionary potential when it optimises for “fitness payoffs” such as fight, flight, feeding, and f…, err, mating, compared with organisms that optimise for truth. In other words, creatures that see the world usefully, rather than accurately, maximise their chances of passing along their genes, while the accuracy-perceiving creatures are weeded out of the gene pool.

He proposes that over the course of millions of years, evolution has favoured organisms that perceive reality in a useful way, rather than an accurate way. Computer simulations have proved repeatedly that, other things being equal, an organism maximises its evolutionary potential when it optimises for “fitness payoffs” such as fight, flight, feeding, and f…, err, mating, compared with organisms that optimise for truth. In other words, creatures that see the world usefully, rather than accurately, maximise their chances of passing along their genes, while the accuracy-perceiving creatures are weeded out of the gene pool.

As Hoffman puts it, “The truth won’t make you free. It will make you extinct.”

So, over the course of time, human perception (and presumably that of other creatures) has progressively crafted an interface between us and the true nature of reality. This interface is extremely useful, and enables us to manipulate our world in ways that are beneficial to our survival and procreation, but we should not mistake it for reality itself.

Hoffman uses the metaphor of a computer desktop. Maybe I have an icon in the top right corner of my desktop that is blue and rectangular and represents a folder. This is not to say that there is an actual blue rectangular object that contains my documents and spreadsheets. The reality is that my data lies in the ones and zeroes in the circuit boards of my computer, but if I had to manipulate the data at the level of electrical impulses (even if I knew how to), it would take me a very long time to get any work done. So successful generations of computer programmers have created this extremely useful interface that enables me to do my work effectively. The user interface on my computer screen conceals the reality of the electrical pulses that constitute my data.

We already know that non-human creatures perceive reality differently than we do. With its bill, the platypus can locate its prey through electroreception. Bats use echolocation to find their way. Snakes can detect infrared. Birds and bees navigate by perceiving polarised light to calibrate their magnetic compass.

Hoffman also points to synaesthetes, the approximately 4% of humans who have some degree of crossover between their senses. He uses the example of Michael Watson, a chef who perceives flavours as physical objects that hover in front of him, invisible, but which he can feel with his hands as if they were real. Mint translates into a smooth column of ice. Angostura bitters becomes a basket of ivy. Other synaesthetes experience numbers as colours, people as sounds, or different musical instruments as a physical sensation in different parts of their body. It’s as if evolution is experimenting with novel ways to perceive reality to see if they enhance or diminish the usefulness of our user interface.

Hoffman also points to synaesthetes, the approximately 4% of humans who have some degree of crossover between their senses. He uses the example of Michael Watson, a chef who perceives flavours as physical objects that hover in front of him, invisible, but which he can feel with his hands as if they were real. Mint translates into a smooth column of ice. Angostura bitters becomes a basket of ivy. Other synaesthetes experience numbers as colours, people as sounds, or different musical instruments as a physical sensation in different parts of their body. It’s as if evolution is experimenting with novel ways to perceive reality to see if they enhance or diminish the usefulness of our user interface.

I will now zero in on the aspects of Hoffman’s theory that especially fascinate me.

Space-time:

Hoffman started out from the “hard problem of consciousness”, the stunning failure of science to explain why we each have a sense of self-ness, as a being that experiences sensory input from our nerve endings, eyes, ears, nose and tongue, and has memories, opinions, and preferences. Neuroscientists have done a good job of identifying “neural correlates of consciousness”, i.e. finding out which parts of the brain respond to which stimuli, but correlation does not establish causation. To date, there is no viable scientific theory that describes how brain activity creates your subjective experience, like the smell of coffee, the sight of a rainbow, the sound of uplifting music, or the thrill of a lover’s touch.

So Hoffman decided to flip the question on its head. If matter does not give rise to consciousness, could it be that consciousness gives rise to matter?

His interim conclusion is that it does, that reality is in fact “a network of conscious agents”, and that space-time, including the neurons that have so fascinated neuroscientists, are a product of that consciousness, created to help us navigate our way through reality.

Could this be what Einstein meant when he said, “Reality is merely an illusion, albeit a very persistent one”?

This theory seems to support the following:

If space-time is a product of consciousness, a shift in consciousness could create an apparent “miracle” that defies our intuitive understanding of reality, but could be possible within this new hypothesis.

This could begin to explain Lynne McTaggart’s Intention Experiments, and the Global Consciousness Project, in which coordinated meditations directed at a specific objective such as peace create a measurable impact on levels of violent crime within the vicinity.

The interaction of more than one consciousness:

Hoffman and his colleagues have created a mathematical representation of consciousness. When they use this to mathematically represent the interaction between two consciousnesses, the resulting representation is also a consciousness, and so on in ever increasing levels of complexity. Consciousness therefore appears to be fractal, with the organism at each level having a degree of consciousness, but not able to access the consciousness of the organisms at the levels above or below. It is like a set of nested Russian dolls, but each doll is unaware of the dolls larger or smaller than itself.

Hoffman and his colleagues have created a mathematical representation of consciousness. When they use this to mathematically represent the interaction between two consciousnesses, the resulting representation is also a consciousness, and so on in ever increasing levels of complexity. Consciousness therefore appears to be fractal, with the organism at each level having a degree of consciousness, but not able to access the consciousness of the organisms at the levels above or below. It is like a set of nested Russian dolls, but each doll is unaware of the dolls larger or smaller than itself.

There is some evidence of this in the lived experience of split-brain patients, the poor unfortunates who not only had to have their corpus callosum severed to treat the most severe forms of epilepsy, but are then subjected to a lifetime of experiments by inquisitive neuroscientists like Roger Sperry and Michael Gazzaniga.

There are reported cases of the two hemispheres having quite different personalities, for example, the woman whose right hand and left hand would fight in the supermarket over what items she wanted to put in her trolley, or the student whose right hemisphere wanted to be a racing car driver, while the left wanted to be a draftsman.

Yet, despite these apparently warring hemispheres, when these split-brain patients were asked if they felt any different after the surgery than they had before, they replied that, other than being freed from their debilitating seizures, they felt the same. This initial answer came from the only verbal hemisphere, the left one, so the researchers asked the right hemisphere the same question, providing it with a pencil or a set of Scrabble letters so it could reply non-verbally, and the right hemisphere produced the same answer: no difference. So even though there was now no physical connection at all between the two hemispheres, the subjective perception of the patient was that they were still a unified consciousness.

So if consciousness is fractal, and perceives itself as unified even in the absence of physical connection, this could disrupt our perception of ourselves as isolated individuals. It could be that all the bacteria, viruses, etc. in my microbiome have a consciousness, albeit a limited one, and that I am the sum total of, and yet somehow more than, these consciousnesses. As in chaos theory, it could be that my whole is greater than the sum of my parts.

Could this unification operate at the species-wide level? The controversial biochemist, Rupert Sheldrake, proposes the theory of morphic resonance, which states that “natural systems… inherit a collective memory from all previous things of their kind”, and that morphic resonance explains “telepathy-type interconnections between organisms”.

Moving to the next step up the scale, James Lovelock’s Gaia hypothesis proposes that the Earth is a self-regulating, synergistic system whose living organisms interact with their ecosystem to optimise conditions for their continued survival. Stephan Harding interprets the hypothesis thus, which sounds very much like a collective consciousness at the planetary level:

“It is at least not impossible to regard the earth’s parts—soil, mountains, rivers, atmosphere etc,—as organs or parts of organs of a coordinated whole, each part with its definite function. And if we could see this whole, as a whole, through a great period of time, we might perceive not only organs with coordinated functions, but possibly also that process of consumption as replacement which in biology we call metabolism, or growth. In such case we would have all the visible attributes of a living thing, which we do not realize to be such because it is too big, and its life processes too slow.”

Beyond a planetary consciousness, at the ultimate stage everything is unified into an overarching collective consciousness (aka God), commensurate with the entire cosmos, and here we are verging on the mystical. The German theologian, Meister Eckhart (1260-1328), is quoted in Aldous Huxley’s The Perennial Philosophy as saying:

“The knower and the known are one. Simple people imagine that they should see God, as if He stood there and they here. This is not so. God and I, we are one in knowledge.”

Huxley also quotes the Blessed John of Ruysbroeck (1293-1381), in a passage which could be interpreted as a holographic representation of consciousness:

“The image of God is found essentially and personally in all mankind. Each possesses it whole, entire and undivided, and all together not more than one alone. In this way we are all one, intimately united in our eternal image, which is the image of God and the source in us of all our life.”

Some modern secular texts, such as Conversations with God, emphasise that “We Are All One” in a way that seems more than metaphorical, representing our sense of self as being something of a delusion that separates us from each other and from our spiritual source.

“We are all One. That is what is meant by ‘whatsoever ye do unto the least of these… ye do unto me.’… Consciousness is a marvellous thing. It can be divided into a thousand pieces. A million. A million times a million. I [God] have divided Myself into an infinite number of ‘pieces’ – so that each ‘piece’ of Me could look back on Itself and behold the wonder of Who and What I Am.”

Even Einstein had something to say on the matter:

“We experience ourselves, our thoughts and feelings as something separate from the rest. A kind of optical delusion of consciousness.”

For sure, at the very least an appreciation of the interconnectedness of all life, if not going as far as “We Are All One”, has been shown to be beneficial to compassion, altruism, and psychological wellbeing.

“A variety of philosophical, religious, spiritual, and scientific perspectives converge on the notion that everything that exists is part of some fundamental entity, substance, or process. People differ in the degree to which they believe that everything is one, but we know little about the psychological or social implications of holding this belief. In two studies, believing in oneness was associated with having an identity that includes distal people and the natural world, feeling connected to humanity and nature, and having values that focus on other people’s welfare… The belief in oneness is a meaningful existential belief that has numerous implications for people’s self-views, experiences, values, relationships, and behavior.”

Death may not be the end:

Daring to go where most scientists would fear to tread, Hoffman proposes that, if his theory of consciousness is correct, that space-time is an illusion and that consciousness gives rise to the phenomenon of matter, death may not be as terminal as Western secular culture would have us believe.

He uses a metaphor from virtual reality: if I and my friends put on our VR headsets to play a game of beach volleyball, we would have the very convincing perception that we were suddenly transported to a beach with a volleyball court, a net, and a ball. We would play for a while inside this virtual interface, and then, maybe, I would say that I am thirsty and I am going to fetch a drink. I take off my VR headset. To my friends, I would appear to either collapse, lifeless, to the ground, or I would disappear altogether, depending on the programming. In either case, I would appear to have expired, but in fact I would simply have stepped out of the interface to get refreshment.

If, as Hoffman suggests, death is no more than stepping out of the earthly interface or, as the Dalai Lama has put it, equivalent to a change of clothes, this would have major impacts on the story that most non-religious people tell themselves about the finality of death, with all the anxiety that brings. Compelling research suggests that fear of death makes us less happy, unsurprisingly, and more materialistic.

Adopting a different belief around death could enable us to opt out of what I call the existential death spiral, in which climate change (or any other existential threat) makes us anxious, so to divert ourselves and/or to create a reassuring external representation of permanence and immortality we go shopping, which exacerbates the very problem that made us anxious in the first place, leading to still greater anxiety, and more retail therapy, and so on.

If death lost its sting, in other words, we would be more relaxed, indulge less in the purchase of superfluous consumer goods, and improve the long-term prospects of our species.

Conclusion:

When ancient wisdom from just about every religious tradition across the world appears to be converging with modern psychological research and theories on the fundamental nature of reality, it is at least worth paying attention to.

For many years I have had a mental image of what is needed in the world, which looks like a deep blue subterranean pool representing our collective consciousness, into which I long to throw a big rock that will send waves of change rippling out through the water. This metaphor depends on the existence of the pool – a dimension in which we are all connected – and it would seem that science is now starting to agree with spirituality that such a dimension exists.

It also depends on the availability of a rock, and for a long time I did not know what this rock might be. Now it seems increasingly obvious to me that I am the rock. You are the rock. We are all rocks with the ability to spread ripples of change. In fact, we are already doing so, but for the most part our ripples are unconscious and lacking in specific intention. Now would be a good time to take our cue from Lynne McTaggart’s Intention Experiments, and start using manifestation to create a better world for everybody.

September 16, 2020

Day 36 – A Parcel of Peace

I’ve been really busy this week, so I’m going to do something I very rarely do, and recycle an old blog post – but somehow, this message from the third leg of the Pacific voyage feels much needed at the moment. As the lockdown tightens once again in the UK, and the US presidential election steps up into an even higher state of crazy, I thought we could all use a parcel of peace.

And just before we get to that, huge congrats to Lia Ditton and Tez Steinberg for their respective successful solo completions of the California-Hawaii route. After the sad deaths of Angela Madsen and Ruihan Yu earlier this year, it is wonderful to get some good news from the world of ocean rowing!

24th May 2010

Dictated by Roz at 9.36pm and transcribed by her mother Rita Savage

Position: -08.10850S, 152.09482E

A calm sky.

A calm sky.My blog to you tonight is a little parcel of peace. But before you open it, find somewhere quiet. It doesn’t have to be quiet around you as long as it is quiet within you. Peace is very fragile, and you don’t want non-peace to get into the box. So no matter what you are doing, put your work aside for now and take three deep, calming breaths. OK now you are ready.

It’s a small box about three inches in each direction. It is a sky blue box with a deep blue ribbon. Go ahead and open it.

Inside you will find a little silver ribbon on a moonlit ocean. The boat is rocking gently, on water barely ruffled by the breeze, and it is pleasantly cool after the heat of the day. There is no sound apart from the slight gurgle of water and the flap of a bird’s wings as it makes its way across the quiet ocean. A few fluffy clouds are glowing like ghosts in the light of the half moon. You feel the sense of accomplishment in a kind of satisfying way; with skin glowing slightly as though from sitting in a chair in the sunshine. (words not at all clear at this point – difficult to transcribe) It is a scene of pure peaceful serenity, soothing and refreshing.

Keep it safe, close the box and retie the ribbon. Put it away and put it in a place where you can find it again any time that you need it, then you can take it out and relax in a moment of calm in this crazy world. This parcel of peace is my gift to you.

Other Stuff:

Another day of good progress today as you may gather from my general air of serenity. Hot, hard, sweaty work and not as calm a sea as yesterday but as my tiredness increases, I just cut the work into shorter shifts so that I manage to keep it going. There is a light wind from the north but it shouldn’t impact me too badly now that I am in a generally northwesterly current. I am about fifty miles from the nearest land, so that is a reasonable margin of safety.

As of tonight, 414 nautical miles to go.

September 10, 2020

Prosperity Without Growth

“The idea of a non-growing economy may be anathema to an economist. But the idea of a continually growing economy is anathema to an ecologist.” – Tim Jackson

I recently re-read Prosperity Without Growth, by Professor Tim Jackson. The first edition was originally released as a report by the Sustainable Development Commission. The study rapidly became the most downloaded report in the Commission’s nine-year history when it was published in 2009. Later that year a reworked version was published as a book, and the following year Tim Jackson spoke at TED. A new, significantly revised and expanded version came out in 2017, so if you haven’t read it recently, you might want to revisit it.

The main thrust of the book is that economic growth has only limited capacity to deliver wellbeing, but huge capacity to trash the planet, so we need to strike a balance between a thriving economy and thriving humans, recognising that one is not synonymous with the other. Let’s take a look at his argument in a bit more detail.

The main thrust of the book is that economic growth has only limited capacity to deliver wellbeing, but huge capacity to trash the planet, so we need to strike a balance between a thriving economy and thriving humans, recognising that one is not synonymous with the other. Let’s take a look at his argument in a bit more detail.

“Prosperity itself – as the Latin roots of the English word reveal – is about hope. Hope for the future, hope for our children, hope for ourselves.”

So it’s only in later years that prosperity has come to be equated with financial wealth. Jackson reminds us that using material consumption as a proxy measure for happiness is both flawed and destructive:

“… living well on a finite planet cannot simply be about consuming more and more stuff… Prosperity, in any meaningful sense of the term, is about the quality of our lives and relationships, about the resilience of our communities and about our sense of individual and collective meaning.”

Central to his case is the need for sustainable and equitable wellbeing. If we simply maximise our own individual wellbeing, at the expense of others who live now and in the future, then this is not true prosperity. We need to find a way to deliver the greatest good to the greatest number over the longest period of time. (I’ve written about this before – see Capitalism vs the Environment – How to End the War.) But the systems we have in place at the moment run counter to that goal.

“Our technologies, our economy and our social aspirations are all badly aligned with any meaningful expression of prosperity… In pursuit of the good life today we are systematically eroding the basis for wellbeing tomorrow. In pursuit of our own wellbeing, we are undermining the possibilities for others. We stand in real danger of losing any prospect of a shared and lasting prosperity.”

[For more on this, please see the wonderful book, #FutureGen: Lessons from a Small Country, by Jane Davidson, the former Welsh Minister for the Environment, who helped create the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 – the first piece of legislation on Earth to place regenerative and sustainable practice at the heart of government.]

It’s clear that we have an obligation to alleviate poverty. More than 3 billion people still live on less than $5 a day. (According to Jason Hickel, overseas aid might help, but halting the systemic exploitation of the Global South would help more – see Of Grabbing and Gifting.) Some countries’ economies clearly do need to grow in order to achieve this.

It’s clear that we have an obligation to alleviate poverty. More than 3 billion people still live on less than $5 a day. (According to Jason Hickel, overseas aid might help, but halting the systemic exploitation of the Global South would help more – see Of Grabbing and Gifting.) Some countries’ economies clearly do need to grow in order to achieve this.

But in the developed world, many countries are definitely seeing diminishing marginal returns on increases in wealth, or even negative returns. Of course, much depends on how the wealth is distributed – for example, in the US, wealth is distributed in a highly unequal fashion, with the wealthiest 1 percent of families holding about 40% of all wealth and the bottom 90% of families holding less than one-quarter of all wealth, and inequality is known to have a negative impact on wellbeing (see The Spirit Level, by Kate Pickett and Richard Wilkinson). But even besides inequality, an additional $1,000 per annum makes a lot less difference to an American than it would to, say, a Malawian.

“Would it not be better to halt the relentless pursuit of growth in the advanced economies and concentrate instead on sharing out the available resources more equitably?”

With a nod to biomimicry, Jackson quotes Richard Wilhelm’s 1923 translation of the I Ching,

“In nature there are fixed limits for summer and winter, day and night, and these limits give the year its meaning.”

But it would seem that humans, or at least many Western humans, rebel against such limits.

“As more and more people achieve higher and higher levels of affluence, they consume more and more of the world’s resources. Material growth cannot continue indefinitely because planet earth is physically limited. Eventually, the scale of activity passes the carrying capacity of the environment, resulting in a sudden contraction – either controlled or uncontrolled. First the resources supporting humanity – food, minerals, industrial output – begin to decline. This is followed by a collapse in population.”

[See my commentary on William Ophuls’ Immoderate Greatness: Why Civilisations Fail, and in the same blog post, Kevin MacKay on Radical Transformation: Oligarchy, Collapse, and the Crisis of Civilization.]

Echoing the famous 1972 report by the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth, Ophuls warns that by the time the signs become obvious, it will probably be too late:

Echoing the famous 1972 report by the Club of Rome, Limits to Growth, Ophuls warns that by the time the signs become obvious, it will probably be too late:

“The process is insidious. Limits constrict by degrees. Decay creeps in unnoticed. It is only late in the game—usually too late to do much about it—that those living become aware of a gradual and imperceptible transformation that has rendered the civilization increasingly tired, depleted, impoverished, vulnerable, and ineffectual.”

Part of the problem is that our world is a complex adaptive system, an intricate and hard-to-map web of connection in which positive feedback loops can suddenly and unpredictably spiral out of control. As our human society increases in complexity, these invisible dynamics become more and more potent agents of chaos.

This is why many of our current problems are being described as “wicked”, a term coined by Alan Watkins and Ken Wilber in Wicked and Wise: How to Solve the World’s Toughest Problems. A wicked problem is multi-dimensional, has multiple stakeholders, multiple causes, multiple syndromes, multiple solutions, and is constantly evolving, even changing in response to attempts to “fix” it. No wonder they’re quite tricky.

So in a perfect world (which we’re not), we would start to act on a problem as soon as we see it coming. There’s a saying in sailing, if you’re thinking about reefing (meaning: reducing the size of the sail to slow the boat in strong winds), you should already be reefing.

But we haven’t done that. We can see the storm coming, but our response is to hoist more and more sail, doubling down and accelerating towards disaster.

We are already in overshoot on four out of the nine critical biophysical boundaries (see my summary of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics).

We are already in overshoot on four out of the nine critical biophysical boundaries (see my summary of Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics).

The IPCC has calculated that to have a better than 50% chance of meeting the target of no more than 1.5 degrees of climate change:

“…the cumulative carbon dioxide emissions released into the atmosphere since 1870 need to be kept below 2,350 billion metric tonnes. So far, more than 2,000 billion tonnes have been emitted. So the maximum available ‘carbon budget’ between now and the end of the century is only 350 billion tonnes. At the current rate of emissions, this budget would be exhausted within a decade. Beyond that point, meeting the target we would have to rely on largely unspecified negative emission technologies.”

I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to bet the future of humanity on technologies that mostly haven’t been invented yet. (Can’t resist – just have to mention the IPAT equation yet again! Even though Technology (T) has the potential to mitigate increases in Population (P) and Affluence (A), it would have to do so at unprecedented speed and scale to get us out of our existential tight spot.)

Jackson goes on to consider eco-economic “decoupling”, meaning that growth in dollars is ‘decoupled’ from growth in physical throughputs and environmental impacts, but rather bleakly concludes that: “this hasn’t so far achieved what’s needed. There are no prospects for it doing so in the immediate future.”

“In short, we have no alternative but to question growth. The myth of growth has failed us. It has failed the 3 billion people who still live on little more than the price of a skinny latte from the café next door. It has failed the fragile ecological systems on which we depend for survival. It has failed, spectacularly, in its own terms, to provide economic stability and secure people’s livelihoods.”

“Prosperity consists in our ability to flourish as human beings – within the ecological limits of a finite planet. The challenge for our society is to create the conditions under which this is possible. It is the most urgent task of our times.”

He then turns to a consideration of what true prosperity means, in terms of what actually makes us feel good. As already mentioned, there has long been an assumption that increasing GDP leads to increasing wellbeing, but surveys reveal that maybe the best things in life are indeed free.

“Health, family, friendships and a fulfilment at work are often mentioned ahead of income or material wealth. Freedom and a sense of autonomy seem to matter. So too does a sense of meaning and purpose.”

So if we are optimising for human wellbeing (see my piece on What Are We Optimising For?), then it would seem that we can have our cake and eat it; we can continue to increase wellbeing while reducing our environmental impact.

Jackson goes on to focus on four foundations for the economy of tomorrow, an economy with the potential to deliver a lasting prosperity:

Enterprise as Service

The primary goal of enterprise must be to provide the capabilities for people to flourish. Second, this must happen without destroying the ecological assets on which our future prosperity depends.

He points to the fringe activities that currently form a kind of “Cinderella economy”, as he calls it (and it is maybe no coincidence that the metaphor is feminine): community energy projects, local farmers’ markets, slow food cooperatives, sports clubs, libraries, community health and fitness centres, local repair and maintenance services, craft workshops, writing centres, outdoor pursuits, music and drama, yoga, martial arts, meditation, gardening, the restoration of parks and open spaces.

He points to the fringe activities that currently form a kind of “Cinderella economy”, as he calls it (and it is maybe no coincidence that the metaphor is feminine): community energy projects, local farmers’ markets, slow food cooperatives, sports clubs, libraries, community health and fitness centres, local repair and maintenance services, craft workshops, writing centres, outdoor pursuits, music and drama, yoga, martial arts, meditation, gardening, the restoration of parks and open spaces.

Work as participation

“Good work offers respect, motivation, fulfilment, involvement in community and, in the best cases, a sense of meaning and purpose in life. Sadly, the reality is somewhat different. Too many people are trapped in low-quality jobs with insecure wages, while others are threatened with long-term unemployment from rapid technological transitions. These processes undermine the creativity of the workforce and threaten social stability.”

He highlights the important psychological benefits of meaningful work, and proposes care, craft, and culture as three economic sectors we should focus on:

“…people often achieve a greater sense of wellbeing and fulfilment, both as producers and as consumers of these material-light, employment-rich activities, than they do in the time-poor, materialistic, supermarket economy in which much of our lives is spent.”

Investment as commitment

“When large proportions of investment are dedicated towards nothing more than asset price speculation, the productive relationship between the present and the future is fundamentally perverted, destabilising the economy and undermining prosperity.”

So we should be investing in the assets on which tomorrow’s prosperity depends, such as schools and hospitals, public transportation systems, community halls, quiet centres, theatres, concert halls, museums and libraries, green spaces, parks and gardens.

“The critical distinction is to invest in assets that maximise our potential to flourish with the minimum level of material consumption, rather than in assets that maximise the throughput of material commodities – irrespective of their contribution to long-term prosperity.”

Money as a social good

“Impact investing – the channelling of investment funds towards ethical, social and sustainable companies, technologies and processes – is an increasingly important element in the financial architecture.”

Examples would be credit unions, Triodos Bank, and sovereign money. Remembering that “the economy is not an end in itself but a means towards prosperity”, this does potentially mean an expansion of the government’s management of the economy, and a corresponding reduction in the role of banks:

“What’s at stake here is the nature of money itself as a vital social good. Money facilitates commercial exchange; it provides the basis for social investment; it has the power to stabilise or destabilise the economy. Handing the power of money creation over to commercial interests is a recipe for financial instability, social inequality and political impotence.”

Conclusion

Tim Jackson doesn’t underestimate the challenge, nor the fineness of the balance that we need to strike.

Tim Jackson doesn’t underestimate the challenge, nor the fineness of the balance that we need to strike.

“Society is faced with a profound dilemma. To reject growth is to risk economic and social collapse. To pursue it relentlessly is to endanger the ecosystems on which we depend for long-term survival… The dilemma, once recognised, looms so dangerously over our future that we are desperate to believe in miracles. Technology will save us. Capitalism is good at technology. So let’s just keep the show on the road and hope for the best.”

Prosperity Without Growth is, ultimately, an optimistic book. Both courage and intellectual rigour are required to face up to the inevitable outcome of our current trajectory, and to examine the assumptions that lead us to remain wedded to our current model of never-ending growth, even when the relationship is doing us harm, and a divorce is long overdue.

After all, humans created the economy in order to make our lives better – more prosperous in the broadest sense of the word. But circumstances have changed dramatically over the centuries – there are now so many of us, living so materialistically, that the system has become a victim of its own success. It has outlived its ability to deliver on the promise of better lives. It is entirely within our power to redesign the economy in ways that get back to its original objectives, and yet somehow the economy has become the master, and we its slaves. It’s time to remember that money is just a story – as Yuval Noah Harari says:

“Money is the probably the most successful story ever told. It has no objective value… but then you have these master storytellers: the big bankers, the finance ministers… and they come, and they tell a very convincing story.”

But we can opt out of that story, and put money back in its place. It is not impossible. As Jackson concludes:

“Impossibilism is the enemy of social change. Time and again, throughout this book, we’ve seen these axiomatic truths dissolve under a more careful scrutiny. A post-growth macroeconomics is after all conceivable… People can flourish without endlessly accumulating more stuff. Another world is possible.”

Other Resources:

More on this in an earlier blog post on my debate with my eco-modernist friend, known here as Socrates: Overconsumption – Must, or Madness?

Also The F-Word: Why Feasible Will Never Get Us Where We Need To Go.

Also check out John de Graaf’s What’s The Economy For Anyway?, referenced in my 2012 blog post on Success – Measure What Matters.

September 3, 2020

A Paradise Built in Hell

In A Paradise Built in Hell: The Extraordinary Communities That Arise in Disaster, Rebecca Solnit looks at how people responded in the aftermath of disasters such as the earthquakes in San Francisco in 1906 and Mexico City in 1985, 9/11, and Hurricane Katrina. What she finds, by delving behind the official accounts and media headlines, is an inspiring picture of the innate intelligence and compassion of human beings, who spontaneously self-organise into communities of mutual support.

Following on from last week’s blog post on biomimicry, and other recent posts on chaotic and emergent systems (like Team of Teams, and Fairness, Floyd, Cooper, Cummings, and Chaos), I was fascinated to read how people, displaced and disrupted by natural or manmade catastrophes, rapidly coalesce into improvised supply chains to provide food, clothing, and shelter for those in need.

I could picture it almost like the Boids computer programme that I linked to last week – immediately after the disrupting event, the Boids/humans are milling around in disarray, but after a couple of beats, points of attraction emerge – a town square, or a church, or a charismatic individual – and people start to gravitate towards them. As they gather, they begin to collaborate, often focusing on meeting the needs of the most vulnerable first. Resources are acquired and distribution mechanisms set in place. It quickly starts to look like an emergent system, with new rules of governance created via the collective intelligence of the crowd.

Many of Solnit’s accounts report how calm people are, and how altruistic. After an earthquake, long before the official first responders can arrive on the scene, neighbours are already working to reach those buried in the rubble, making the most of the crucial period immediately after the buildings have collapsed when the chance of finding survivors is the greatest. Media reports tend to focus on the official response, largely because the reporters arrive around the same time as the uniformed professionals, at which point civilians are usually banished from the scene. So the version of the story that makes it into the media tends to exaggerate the role of the official responders, who are indeed brave and skilful at their jobs and deserving of praise, but the downside of this emphasis is that the role of ordinary people to serve and save their neighbours is downplayed.

Many of Solnit’s accounts report how calm people are, and how altruistic. After an earthquake, long before the official first responders can arrive on the scene, neighbours are already working to reach those buried in the rubble, making the most of the crucial period immediately after the buildings have collapsed when the chance of finding survivors is the greatest. Media reports tend to focus on the official response, largely because the reporters arrive around the same time as the uniformed professionals, at which point civilians are usually banished from the scene. So the version of the story that makes it into the media tends to exaggerate the role of the official responders, who are indeed brave and skilful at their jobs and deserving of praise, but the downside of this emphasis is that the role of ordinary people to serve and save their neighbours is downplayed.

In many cases, the official response actually makes things worse, rather than better. Katrina was a case in point, with a laggardly, inadequate, and often inhumane response from the authorities.

“At large in disaster are two populations: a great majority that tends toward altruism and mutual aid and a minority whose callousness and self-interest often become a second disaster.”

This latter is called “elite panic”, the phrase coined by Rutgers University professors Caron Chess and Lee Clarke for the fear felt by those with the most to lose.

“…to heck with this idea about regular people panicking; it’s the elites that we see panicking. The distinguishing thing about elite panic as compared to regular-people panic, is that what elites will panic about is the possibility that we will panic. It is simply, more prosaically more important when they panic because they’re in positions of influence, positions of power.”

“Elite panic in disaster, as identified by the contemporary disaster scholars, is shaped by belief, belief that since human beings at large are bestial and dangerous, the believer must himself or herself act with savagery to ensure individual safety or the safety of his or her interests.”

Original caption for this photo: “Looters make off with merchandise from several downtown businesses in New Orleans, Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2005, after Hurricane Katrina hit the area. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)”

Original caption for this photo: “Looters make off with merchandise from several downtown businesses in New Orleans, Tuesday, Aug. 30, 2005, after Hurricane Katrina hit the area. (AP Photo/Eric Gay)”This was particularly evident in the aftermath of Katrina, when vigilante groups defended privileged neighbourhoods against the perceived threat of looters, shooting people (almost without exception people of colour) who they suspected of ill intent, based more on their mere presence and the colour of their skin, rather than on any evidence. Solnit also points out how the racial bias of the media often manifested in reports of this process of distributing necessary goods – black people were reported to be “looting”, while white people were said to be “requisitioning supplies”.

As with so many of the narratives currently dominant in our world:

“Disaster myths are not politically neutral, but rather work systematically to the advantage of elites. Elites cling to the panic myth because to acknowledge the truth of the situation would lead to very different policy prescriptions than the ones currently in vogue.”

So let’s dive into that last sentence a little further. Humans have emerged as the dominant successful species (rather too dominant, and too successful, some might argue) because we are good at cooperation. And we were good at cooperation long before there were laws and structures to force us to cooperate. It was a biological and evolutionary imperative. As creatures go, we’re not particularly fast or strong, and our senses are positively dull compared with many other species. But, as Yuval Noah Harari points out in Sapiens, humans are really good at cooperation and adaptation – both being qualities that disasters call forth.

Looking to the future, there is every chance that we are going to see more and more disasters. Climate change leads to more severe weather events – floods, hurricanes, maybe even earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Climatic volatility tends to lead to political instability, which can lead to manmade disasters and sudden mass migrations. Elites, desperately clinging to power, will default to old-school command-and-control strategies, trying to hold back the tide of disruption that threatens their power base. The image of King Canute comes to mind.

Kerala, India

Kerala, IndiaSo what would it be like if we had leaders that recognised where the world is heading, and gave us back the rights to our freedom, autonomy and creativity, that recognised that the majority of human beings are resourceful, kind and generous and allowed us to express the better angels of our nature as millennia of evolutionary biology have conditioned us to do? Simply put, what if we were allowed to be more self-organising?

Contrast this narrative with the narrative put forward in his book, tellingly titled Propaganda, by Edward Bernays who is credited (or blamed) as the godfather of the modern-day advertising industry:

“The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country… In almost every act of our daily lives, whether in the sphere of politics or business, in our social conduct or our ethical thinking, we are dominated by the relatively small number of persons…who understand the mental processes and social patterns of the masses. It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind.”

Which of these narratives do we want to hold to be true? Are we capable of organising ourselves in civilised, dignified, and compassionate ways? Or are we puppets to be manipulated by a small number of cynical, powerful people pursuing their own ambitious ends?

At the moment, I would say that both are true. But both don’t have to be.

Solnit’s conclusion is that:

“In the wake of an earthquake, a bombing, or a major storm, most people are altruistic, urgently engaged in caring for themselves and those around them, strangers and neighbors as well as friends and loved ones. The image of the selfish, panicky, or regressively savage human being in times of disaster has little truth to it.”

And in fact, there may even be gifts in the coming disruptions. They may be immensely traumatic and painful in the short term, but as I wrote a few weeks ago (If You’re Not Living On The Edge..), the cool stuff happens at the edge of chaos, where the fragile faux-stability of the old order rubs up against the vibrant potentiality of the as-yet-unknown.

You’ve probably heard the parable of the chopsticks:

A very old man knew that he was going to die very soon. Before he died he wanted to know what heaven and hell were like, so he visited the wise man in his village.

“Can you please tell me what heaven and hell are like?” he asked the wise man.

“Come with me and I will show you”, the wise man replied.

The two men walked down a long path until they came to a large house. The wise man took the old man inside, and there they found a large dining room with enormous table covered with every kind of food imaginable. Around the table were many people, all thin and hungry, who were holding twelve-foot chopsticks. Every time they tried to feed themselves the food fell off the chopsticks.

The old man said to the wise man, “Surely this must be hell. Will you now show me heaven?”

The wise man said, “Yes, come with me.”

The two men left the house and walked farther down the path until they reached another large house. Again they found a large dining room and in it a table filled with all kinds of food. The people here were happy and appeared well fed, but they also held twelve-foot chopsticks.

“How can this be?” said the old man. “These people have twelve-foot chopsticks and yet they are happy and well fed.

The wise man replied, “In heaven the people feed each other.”

The point is, heaven and hell might be much the same… but in heaven, everybody helps each other.

This, I believe, will be the invitation of our times: can we learn to support each other during this chaotic, exciting, creative liminal space of transformation? I believe we can, especially when we trust in the power of self-organising, biomimetic, mutually supportive communities, bound by love and trust and the understanding that we live or die… together.

August 27, 2020

Biomimicry: Because Mother Nature Has Got Creativity and Resilience Nailed

For the last couple of years I’ve had a growing interest in biomimicry, looking to nature to inspire the design of products or systems. Of those two, I’m far more interested in the systems aspect – how do we adopt and adapt nature’s principles to create social systems that are creative and resilient?

I’ve written up this list of biomimetic features that I believe will be valuable in creating a more peaceful and sustainable, yet still dynamic and innovative, world – or any subset of the world, like organisations, businesses, economies, communities, etc.

To create this list, I started with a list from an article in Wired Magazine, which in turn was distilled from the wisdom of Janine Benyus, Michael Braungart and William McDonough, Kevin Kelly, Steven Vogel, D’Arcy Thompson, Buckminster Fuller, Julian Vincent, and Dee Hock. Then I’ve added to it from my own reading of thinkers like Elinor Ostrom, Margaret Wheatley, Barbara Marx Hubbard, Riane Eisler, Bernard Lietaer, Frederic Laloux, Iain McGilchrist, Otto Scharmer and Stan McChrystal (the links are to past blog posts I’ve written about their work, and see also my post on the Shift in Consciousness).

I’ll start out with a section on flocking behaviour, which consists of three simple rules, and then I’ll go into a selection of other principles. This is just a short introduction, and this list of principles is by no means exhaustive, but I hope it might inspire some thoughts on how you can bring more biomimicry into your own life and work. I really believe biomimicry holds important clues to the future organisation of our world.

Flocking

As Mitchell Waldrop sets out in Complexity, there are three simple rules that determine flocking behaviour, as programmed into the Boids algorithm (there is also a short video explaining this):

separation: steer to avoid crowding local flockmates

separation: steer to avoid crowding local flockmatesalignment: steer towards the average heading of local flockmates

cohesion: steer to move towards the average position (centre of mass) of local flockmates

This model can be replicated in organisations to promote effectiveness, unity of purpose, and flat-structured collaboration.

To say more about each of these three dynamics:

Separation

Nature abhors a vacuum, so it diversifies to fill every niche. Think of leaves optimising for photosynthesis. When a tree falls in the forest, it doesn’t take long before opportunistic plants grow to fill the space. Even within a single plant, leaves pivot to optimise their exposure to sunlight, avoiding the shade of leaves higher up. Every space is filled, but not over-filled. Survival of the “fittest” doesn’t mean the strongest or fastest – it means the organism that is best adapted to fit in with its environment.

Alignment

For self-organisation to work, there needs to be a shared sense of overall direction that arises organically from the collective. Instead of trying to predict and control the future, the flock/organization has a life and a sense of direction of its own. Everyone is invited to listen in and understand what the organization wants to become, what purpose it wants to serve. Margaret Wheatley calls this its Evolutionary Purpose.

Cohesion

Nature rewards cooperation. A large area of forest is exponentially more diverse and productive than a small area of forest. A flock or herd can better protect its young and vulnerable. Likewise, a grouping of humans or human-created enterprises can create a richer ecosystem than isolated ones – think of a city’s theatre district, or business district, or restaurant district, where geographical proximity improves, rather than diminishes, the prospects of its inhabitants.

And now onto some other examples:

Self-assembling

The organisation creates itself from the ground up. In nature, single cells combine to become multi-celled organisms, which combine to create higher-order organisms (like humans: see I Contain Multitudes), which create superorganisms, ecosystems and societies. The organisation is fractal, in the sense that it is self-similar at all scales – think of a tree, in which each tree branch, from the trunk to the tips, is an approximate copy of the one that came before it. This creates resilience, because you can chop the organism/organisation into smaller pieces, and each piece will still be able to function independently of the whole.