Roz Savage's Blog, page 11

January 7, 2021

Favourite Books of 2020

Happy New Year to you! (Although if you’re in the US, it may not be so happy thus far – and you have my condolences, commiserations, and sympathy.)

I took a blissful two weeks (mostly) offline over my birthday (it’s not too late to wish me a happy one!), Christmas and New Year. Towards the middle of December I noticed I was feeling really tired, and realised I hadn’t had a holiday since sometime in 2019, and I’m not even sure I had one then. This is the mixed blessing of doing work I love – even though my work inspires and energises me, I still need a break occasionally. So I cleared my diary for two weeks, to do precisely whatever I felt like doing, and have come back feel refreshed.

Part of what I felt like doing was a review of 2020, including a review of what I’ve learned and what topics have fascinated me.

High-level Summary of 2020’s Shiny New Ideas (with links to associated blog posts):

Reality, especially recognising that reality is not a bunch of static objects, but rather a web of interlocking complex systems, giving rise to emergent properties (and emergent solutions) at the edge of chaos

Taoism, Buddhism and the cycles of life

Race, race, and race

Economics as a powerful lever of societal change (expect to hear a lot more about this in 2021)

Biomimicry (and the more I learn about nature, the more intelligent I realise it is – but indigenous culture has recognised this for aeons)

Apocalypse (2020 was a good year for this one), and yet there are reasons to be cheerful

Everyday magic

And now onto a quick recap of some of my most formative/favourite books of the year.

The Case Against Reality: How Evolution Hid the Truth from Our Eyes, by Don Hoffman

Don Hoffman

Don HoffmanIf you’re a regular reader, you will know that this book had a big impact on me, and I have mentioned it often. Cognitive psychologist Don Hoffman asked himself: if we have so far failed to explain how matter gives rise to consciousness, then maybe we’re coming at this from the wrong end… what if consciousness gives rise to matter? And he goes on to present a compelling case, based in evolutionary biology, that we (and probably all other species) have evolved to perceive reality in a way that is useful, rather than accurate. So if we think that what we see around us is reality as it actually is, we are sorely mistaken.

“The problem is not that our perceptions are wrong about this or that detail. It’s that the very language of objects in space and time is simply the wrong language to describe objective reality.”

To me, this is the joker in the pack, the get-out-of-jail-free card to our environmental/existential crisis. If space-time is no more than a construct of our minds, can we transcend it? Can apparent miracles happen?

More about The Case Against Reality in my blog posts:

Just How Real Is Reality, Really?

Reality, Russian Dolls, Rocks and Ripples

Immoderate Greatness: Why Civilisations Fail, by William Ophuls

A reading list for 2020 wouldn’t be complete without a good dose of apocalypse. For a short but powerful account of six reasons why we’re screwed (in conventional space-time reality, anyway), I highly recommend Immoderate Greatness. It’s hard to argue with the logic of a statement such as:

“A developing civilization grows steadily more complex and increasingly less manageable over time, preparing the way for its eventual demise. Only a race of supremely intelligent, rational, and wise beings could so order their affairs and so limit their behaviour as to avoid this outcome. Human beings are not such a race.”

And yet… could we become such a race? I still hold out hope that our current challenges will inspire us to raise our game and genuinely put the sapiens into homo.

Blog post (with possibly my favourite blog title of the year): The Ecological Elephant in the Room Goes up the Creek Without a Paddle

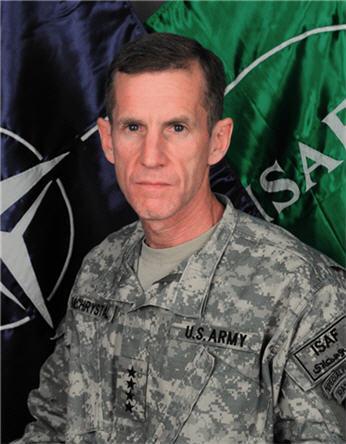

Stan McChrystal

Stan McChrystalTeam of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World, by General Stanley McChrystal

When Stan McChrystal arrived in Afghanistan in 2003 to head up the Joint Task Force, he found a lumbering, monolithic task force being run ragged by low-tech but nimble cells of insurgents. To beat them, the US military had to become more like them. Decision-making was decentralised, information flows massively improved, and iterations accelerated to create a “shared consciousness” across the organisation. It went from being an old-school hierarchy of command-and-control to more of a self-organising, biomimetic, organic system – with a huge increase in its effectiveness.

“The temptation to lead as a chess master, controlling each move of the organization, must give way to an approach as a gardener, enabling rather than directing. A gardening approach to leadership is anything but passive. The leader acts as an “Eyes-On, Hands-Off” enabler who creates and maintains an ecosystem in which the organization operates.”

Whether or not you agree with the objectives of the task force, or militarism generally, there is a lot to be learned about how organisations need to rethink and remodel themselves to operate in our complex and interconnected 21st century society, where results are increasingly unpredictable and long-term plans are increasingly irrelevant.

Blog post: Team of Teams

Finding Our Way: Leadership for an Uncertain Time, by Margaret Wheatley

As a less combative complement to Team of Teams, I highly recommend Finding Our Way. With her vast experience of working with organisations to help them become more effective, while also respecting the autonomy and dignity of the individual, Meg Wheatley has lots of very practical advice, again emphasising decentralisation, relevant metrics, and informative feedback flows. This calls for a different kind of leadership.

“Leaders who live in the new story help us understand ourselves differently by the way they lead. They trust our humanness; they welcome the surprises we bring to them; they are curious about our differences; they delight in our inventiveness; they nurture us; they connect us. They trust that we can create wisely and well, that we seek the best interests of our organisation and our community, that we want to bring more good into the world.”

She is a powerful advocate for the messiness of self-organising systems – what they lose in efficiency, they gain in adaptability, flexibility, self-regeneration, resilience, learning capacity, and intelligence.

Blog post: Finding our Way

The Sheer, Jaw-Dropping, Mind-Blowing Amazingness of Nature

This isn’t the title of a book (although maybe it should be), but rather my heading for a group of books about (non-human) nature that repeatedly blew my mind. The more we learn about the natural world, the more intelligence we find, absolutely everywhere we look, until reality really does start to look and feel like Hoffman’s “network of conscious agents”. Consciousness and intelligence seem to be everywhere once we realise that not all consciousness looks like human consciousness, and not all intelligence requires a brain.

I read these books fairly close together in time, and appreciate how they harmonise together and reinforce each other’s messages.

Robin Wall Kimmerer

Robin Wall KimmererBraiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, by Robin Wall Kimmerer

Blog post: Braiding Sweetgrass, Kiss the Ground, and Other Hints of Hope

“Philosophers call this state of isolation and disconnection “species loneliness”—a deep, unnamed sadness stemming from estrangement from the rest of Creation, from the loss of relationship. As our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated, more lonely when we can no longer call out to our neighbours.”

How to Change Your Mind: The New Science of Psychedelics, by Michael Pollan

Blog post: Beyond the Doors of Perception

“When Huxley speaks of the mind’s “reducing valve”—the faculty that eliminates as much of the world from our conscious awareness as it lets in—he is talking about the ego. That stingy, vigilant security guard admits only the narrowest bandwidth of reality, “a measly trickle of the kind of consciousness which will help us to stay alive.”

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds and Shape Our Futures, by Merlin Sheldrake

No blog post yet

“A mycelial network is a map of a fungus’s recent history and is a helpful reminder that all life-forms are in fact processes not things. The “you” of five years ago was made from different stuff than the “you” of today. Nature is an event that never stops. As William Bateson, who coined the word genetics, observed, “We commonly think of animals and plants as matter, but they are really systems through which matter is continually passing.”

Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm: Beyond the Doors of Perception into the Dreaming of Earth, by Stephen Harrod Buhner

No blog post yet – I’m only half way through, but I had to list this one. I’ve probably highlighted about 25% of the text. One OMG after another.

“All life-forms are a kind of living information, transforms, as Bate-son put it, of messages. Not, by any means, actors against a static background. But rather, information added to an already extant and very complex information system. There is, in consequence, a pattern that connects each part to each other and to the whole. A pattern that runs through everything that Gaia has done.”

The Gifts of Solitude: A Short Guide to Surviving and Thriving in Isolation, by Roz Savage

And finally, terrible as I am at marketing, I thought I should mention my own book, published in April in response to the Covid lockdown, to help both extroverts and introverts through these challenging times, drawing heavily on my own struggles and triumphs with solitude on the ocean.

“It’s tempting to extrapolate into the future and decide we can’t face it. It’s the brain’s job to keep us safe, so it loves to gallop off into the unknown and project our deepest fears into it. I had to learn to say, “Thank you, brain, for doing such a great job of flagging up all the things that could go wrong. I will do what I can to prepare for them. But I’m also going to remember that these are imaginings, not reality. In the past things have hardly every turned out how I expected them to, and they probably won’t this time either. So let’s stay in the present and simply wait and see what happens.”

I published various excerpts from The Gifts as blog posts, so you can even try before you buy.

Other Stuff:

TEDxStroudWomen has now rebranded as TEDxStroud, as our Covid-rescheduled date of 21st March no longer coincides with the global TEDWomen event. But we still have our original lineup of amazing speakers, and are ramping up our preparations for our virtual livestream on the equinox. Tickets will be available soon, so stay tuned! Meanwhile, you can follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube.

Print your favourite blog as an annual: As a rather self-indulgent present to myself, I got my blog posts printed up into hardcopy books, with one volume per year for 2018, 2019, and 2020. I ordered them through Pixxibook, which was pricey, but the quality is really lovely. If you have a favourite blog (maybe even this one?!) that you would like to have printed and bound, I’d happily recommend Pixxibook. (And no, I’m not on commission!)

December 18, 2020

A Farewell to 2020

This will be my last blog post of the year, and it’s hard to know what to say about 2020. I’m not going to give in to the glibness and gallows humour of “it’s all been terrible”, because I really believe that the hardest times are the greatest teachers.

But how to sum up in a few short words a year that has been dominated worldwide by the coronavirus, an invisible foe that has infected an estimated 74.2 million people worldwide, and been a factor in 1.65 million deaths? For those of you who will be missing someone you love this festive season, you have my sympathy and best wishes.

Then there has also been George Floyd and Black Lives Matter, 5G, Brexit, Sussexit, Trump and the US presidential election, and of course the billions of daily dramas, big and small, that loom large for each of us as individuals, families, and communities.

For me personally, it has been a year to remember for The Gifts of Solitude, TEDxStroudWomen, my doctoral programme (on Wednesday I submitted what I hope is my final version, so fingers crossed I may become Dr Roz early next year), the Sisters, and the SEEDS currency (of which you will probably hear much more in 2021). It has been my first full year in Gloucestershire, and I have counted my blessings every single day to live surrounded by so much natural beauty, and to be able to get out for my daily walks even at the height of the pandemic.

For me personally, it has been a year to remember for The Gifts of Solitude, TEDxStroudWomen, my doctoral programme (on Wednesday I submitted what I hope is my final version, so fingers crossed I may become Dr Roz early next year), the Sisters, and the SEEDS currency (of which you will probably hear much more in 2021). It has been my first full year in Gloucestershire, and I have counted my blessings every single day to live surrounded by so much natural beauty, and to be able to get out for my daily walks even at the height of the pandemic.

As usual, I’ll be doing a big year-end review, and an envisioning exercise for the coming year. My gut feeling about 2021 is that it will be a year of challenge and transformation – we will see the ongoing fallout of the COVID-induced economic downturn, which will cause great hardship for many – and as so often happens, crisis will birth new and hopefully better ways of doing things.

I don’t have a crystal ball, so your guess is as good as mine, but in 2021 I expect to see a growing number of women stepping up into positions of leadership. I see dramatic changes in how we work, with a lot less office space and a lot more working from home, with an associated flow of people out of cities and into the countryside in search of a better quality of life once they are no longer tethered to a daily commute. I hope that this will be accompanied by workers having more autonomy and being treated as responsible adults, with more emphasis on actual results rather than competing over who can put in the most hours at the office. And I hope we see a reprioritisation, as people have had more time during furloughs and lockdowns to reflect on what matters – matters of health, relationships, work/life balance, time in nature, and a sense of purpose.

Environmentally…. I wonder. While it is tremendously encouraging to see cities like Amsterdam, Portland and Philadelphia embracing Doughnut Economics, and the drop in carbon emissions with the dramatic reduction in flights and travel generally, but atmospheric CO2 continues to rise, and I’m not at all reassured that the UK government is doing a good job of preparing for COP26 (Christiana Figueres, where are you when we need you?!).

As to how history will regard 2020, it is too soon to tell. Astrologers and empaths are predicting a deep shift in humanity’s collective psyche, starting from the winter solstice on Monday. I know little about such things, but I do sense that change is in the air. It’s likely to be a bumpy ride for some time to come, but I’m cautiously optimistic that ultimately, we will look back on 2020 as a turning point for the better.

Meanwhile, wishing you a very merry midwinter/saturnalia/Yule/ Chanukah/Eid/Christmas/non-specific holiday, and I will see you in 2021!

Thank you to James Parker for The Coronavirus Prayer, first published in The Atlantic.

Dear Lord,

In this our hour of doorknobs and droplets,

when masks have canceled our personalities;

in this our hour of prickling perimeters, sinister surfaces,

defeated bodies, and victorious abstractions,

when some of us are stepping into rooms humid with contagion,

and some of us are standing in the pasta aisle;

in this our hour of vacant parks and boarded-up hoops,

when we miss the sky-high roar of the city

and hear instead the tarp that flaps on the unfinished roof,

the squirrel giving his hingelike cry, and the siren constantly passing,

to You we send up our prayer, as follows:

Let not heebie-jeebies become our religion,

our new ideology, with its own jargon.

Fortify us, Lord. Show us how.

What would your saints be doing now?

Saint Francis, he was a fan of the human.

He’d be rolling naked on Boston Common.

He’d be sharing a bottle. No mask, no gloves,

shielded only by burning love.

But I don’t think we’re in the mood

for feats of antic beatitude.

In New York City, and in Madrid,

the saints maintain the rumbling grid.

Bless the mailman, and equally bless

the bus driver, vector of steadfastness.

Protect the bravest, the best we’ve got.

Protect the rest of us, why not.

And if the virus that took John Prine

comes, as it may, for me and mine,

although we’ve mostly stayed indoors,

well—then, as ever, we’re all Yours.

Until further notice,

AMEN

Other Stuff:

I thoroughly enjoyed this conversation with Flint Mitchell for the Seeking Authenticity podcast.

We had our second TEDxStroudWomen webinar last Tuesday evening, on how to speak in public. I got together with two amazing women to talk about the good, the bad, and the ugly of getting onstage. You can enjoy it here on YouTube. We’ll be having more webinars on TEDx-related topics in the New Year, so stay tuned for those.

December 10, 2020

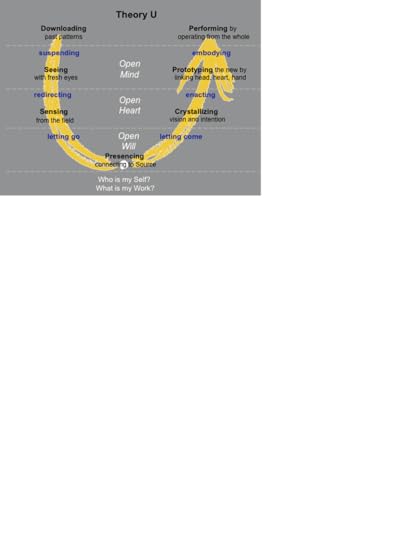

Presence and Presencing

A super-quick blog post today, heavily plagiarised from my doctoral dissertation, as I’m doing a full-time online course this week with the Presencing Institute. If you’re not familiar with Presencing, it’s a blended word formed from sensing (feeling the future possibility) and presence (the state of being in the present moment). It means sensing and actualizing one’s highest future possibility—acting from the presence of what is wanting to emerge.

If you think this all sounds a bit fluffy, you might be surprised to hear that it was founded by a German lecturer at MIT’s Sloan School of Management called Otto Scharmer. He co-founded the Presencing Institute in 2006, and in 2009 he and Katrin Kaufer published Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges. Described as an “action research platform at the intersection of science, consciousness, and profound social and organizational change”, the Presencing Institute has had a significant and widespread impact on addressing global challenges such as the ecological crisis, inequality, finance, healthcare and education.

Summarising their work as enabling the transition “from ego-system to eco-system”, the Institute identifies three fundamental disconnects that need to be healed in order to create an equitable and sustainable future: the ecological divide, the social divide, and the spiritual divide.

It was quite a few years ago that I first encountered this model, and it immediately made sense to me. I had been saying for a while that our environmental challenges resemble a many-headed sea monster – we can cut off the heads of climate change, deforestation, plastic pollution, etc., but until we get to the heart of the monster, it will simply keep sprouting new heads – and the heart is the mistaken idea that we are somehow separate from nature, independent of it, rather than deeply interconnected with it. It is only when this interdependence is fully understood that we will start to treat the natural world with the respect it deserves, recognising that to harm nature is to harm ourselves. It is maybe one of the biggest failures of the environmental movement’s communications that it has focused on “save the whale” or “save the planet”, when an appeal to “save the humans” might have galvanised swifter and more effective action.

It is easy to see how this disconnect came about. Nature can appear unfriendly, even dangerous – and I speak from personal experience. Early man understandably wanted to protect himself from famine and drought, extremes of heat and cold, and so he systematically set about creating a more comfortable and secure life with agriculture and homes, and later supermarkets and supply chains. In the course of this systematic attempt to conquer nature, most of us have become tragically disconnected from the systems that support life, to the extent that we liberally douse our land in pesticides, herbicides, and industrial pollutants, somehow imagining that we will be immune to the cumulative effects.

The Presencing Institute uses the emergent properties of working groups to generate creative new ideas. Theory U refers to the process of letting go of preconceptions in order to open up to new insights that are wanting to emerge from the collective intelligence in the room (or the “Field” or from “Source”, if those words resonate with you).

This concept was in part inspired by a conversation that Scharmer’s colleague and collaborator, Joe Jaworski, had in London with the physicist David Bohm, concerning the implicate order of reality. Bohm took two cylindrical jars, one slightly smaller than the other, with the smaller one having a crank on top. He placed the smaller cylinder inside the larger one, and filled the space between with viscous glycerine. When he placed a single drop of ink in the glycerine and turned the crank, the ink was drawn out to a fine ribbon until it seemed to disappear. When he reversed the motion of the inner cylinder the ink reformed to its original state as a visible drop. (You can watch a version of the experiment here – it’s quite stunning.)

What Bohm was illustrating here was that we think that the object, or ink drop, ceases to exist when we can no longer see it, but it does exist – it has merely returned from the explicate to the implicate world. As Jaworski writes:

“All matter and the universe are continually in motion. At a level we cannot see, there is an unbroken wholeness, an ‘implicate order’ out of which seemingly discrete events arise. All human beings are part of that unbroken whole, which is continually unfolding. Two of our responsibilities in life are to be open and to learn, thereby becoming more capable of sensing and actualizing emerging new realities.”

This insight proved to be a major influence on Jaworski, and subsequently also on his colleagues Peter Senge, Otto Scharmer and Adam Kahane, all of whom have used different flavours of this idea in their work. Jaworski wrote:

“Bohm had shared with me in London an explicit mental model of the way he believed the world works and the way he believed human beings learn and think. To Bohm it was clear that humans have an innate capacity for collective intelligence. They can learn and think together, and this collaborative thought can lead to coordinated action. We are all connected and operate within living fields of thought and perception. The world is not fixed but is in constant flux; accordingly, the future is not fixed, and so can be shaped. Humans possess significant tacit knowledge—we know more than we can say. The question to be resolved is how to remove the blocks and tap into that knowledge in order to create the kind of future we all want.”

This meeting influenced Jaworski’s work with the American Leadership Forum, which he founded. Through intensive courses and retreats, he sought to optimise the conditions for emergence. He saw the process as mystical, and yet reliably consistent.

“C. G. Jung’s classic, ‘Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle’, defines synchronicity as ‘a meaningful coincidence of two or more events, where something other than the probability of chance is involved’. In the beautiful flow of these moments, it seems as if we are being helped by hidden hands… Over the years my curiosity has grown, particularly about how these experiences occur collectively within a group or team of people. I have come to see this as the most subtle territory of leadership, creating the conditions for ‘predictable miracles.’”

It’s a powerful methodology. If I needed convincing that it can work, yesterday I was in a breakout room with three others, none of whom knew anything about me. One person described a current challenge, while we practiced deep listening, and then we had to report back on what images came up for us. One of the participants described her mental image: a rowboat with no oars.

I’m not saying it’s connected to my Atlantic experience, but I’m also not saying it’s not connected…

Other Stuff:

#SHEChangesClimate: Over the last few weeks I’ve been part of a rapid response group of women, ably organised by the indefatigable Antoinette Vermilye in response to the announcement of an all-male senior leadership team for the crucial COP26 climate talks being hosted by the UK next year.

Today we sent an open letter to the UK Government, calling on them for greater accountability and transparency on gender equality in the COP26 leadership team.

Our letter calls for 50:50 split of men and women in the UK COP26 top leadership team has been supported by over 400 high level signatures. Signatories include: Cherie Blair, Martha Lane-Fox, Caroline Lucas, Bella Lack, Wanjira Maathai, Rosie Boycott, Sandrine Dixson-Decleve, Livia Firth, Ellie Goulding, Kate Raworth, Fiona Reynolds, Mary Robinson, Amber Rudd, Vandana Shiva, Eve Ensler,

You can support our campaign via our website and on social media.

TEDx Webinar: Following on from the success of our first TEDxStroudWomen webinar, we will be holding our second one next Tuesday 15th December, in which I will be chatting with two highly experienced speakers about the challenge of speaking in public, and what it takes to be an effective communicator. If you’re an aspiring or actual public speaker, this one’s for you! Please REGISTER HERE in order to receive your link to the event.

December 3, 2020

Beyond the Doors of Perception

“If the doors of perception were cleansed every thing would appear to man as it is, Infinite. For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things thro’ narrow chinks of his cavern.”

― William Blake

If you think you’re living in the real world, you’re mostly mistaken.

If you’ve been reading my blog for a while, you’ll know that I’m fascinated by, amongst other things, the nature of reality. It’s fairly uncontroversial to say that our perception of the world is shaped by our experiences, the survival imperative, and by the capabilities and limitations of human sensory organs (see my notes on Deviate, by Beau Lotto, and Liminal Thinking, by Dave Gray). You might even be willing to believe that what we think is reality, is in fact just a very handy user interface for interacting with the world around us (see The Case Against Reality, by Don Hoffman).

But if “reality” is indeed just a user interface, then what is the truth that lies behind it? If we don’t have the sensory organs to perceive it, how can we ever know it?

The good news, it seems, is that we do have ways to perceive it, to open the doors of perception – it’s just that culturally we have decided to keep the doors shut… because who knows what might happen if the truth were to get out? The fragile edifice of our exploitative, dominator-style culture would crumble, that’s what.

Okay, that was quite a leap. Let me rewind and build my case more slowly.

I recently finished reading How To Change Your Mind, by Michael Pollan, also well known for The Omnivore’s Dilemma. I suppose that, in all honesty, I suppose I should also disclose the subtitle of How To Change Your Mind, in case you don’t already know it: it’s “The New Science of Psychedelics”. I realise that the word “psychedelics” may provoke an emotional response in many readers – images of the 60s, loud swirly patterns, drug addicts, bad trips, Timothy Leary, turning on, tuning in, and dropping out. But for a moment, I’d like to invite you to set aside preconceptions, and maintain an open mind… with the opening of minds being exactly the point of this blog post. (I should maybe also say that I have not had any psychedelic experiences myself, although I am intensely psychedelicurious.)

I recently finished reading How To Change Your Mind, by Michael Pollan, also well known for The Omnivore’s Dilemma. I suppose that, in all honesty, I suppose I should also disclose the subtitle of How To Change Your Mind, in case you don’t already know it: it’s “The New Science of Psychedelics”. I realise that the word “psychedelics” may provoke an emotional response in many readers – images of the 60s, loud swirly patterns, drug addicts, bad trips, Timothy Leary, turning on, tuning in, and dropping out. But for a moment, I’d like to invite you to set aside preconceptions, and maintain an open mind… with the opening of minds being exactly the point of this blog post. (I should maybe also say that I have not had any psychedelic experiences myself, although I am intensely psychedelicurious.)

Since time immemorial, humans have used plants (and occasionally toads) to experience altered states of consciousness. Such states can also be achieved through meditation, certain breathing exercises (like Holotropic Breathwork), sensory deprivation, fasting, prayer, overwhelming experiences of awe, extreme sports, and near-death experiences (I recommend you don’t try this last one at home.) Michael Pollan set out, from a position of slight nervousness and definite scepticism, to find out why.

He was surprised by some of the advocates he encountered. At a dinner party in Berkeley, he encounters a prominent psychologist who:

“felt that LSD gave her insight into how young children perceive the world. Kids’ perceptions are not mediated by expectations and conventions in the been-there, done-that way that adult perception is; as adults, she explained, our minds don’t simply take in the world as it is so much as they make educated guesses about it. Relying on these guesses, which are based on past experience, saves the mind time and energy… LSD appears to disable such conventionalized, shorthand modes of perception and, by doing so, restores a childlike immediacy, and sense of wonder, to our experience of reality, as if we were seeing everything for the first time.“

Bob Jesse, a monk living in a remote mountaintop cabin, related:

“What stands out most for me is the quality of the awareness I experienced, something entirely distinct from what I’ve come to regard as Bob. How does this expanded awareness fit into the scope of things? To the extent I regard the experience as veridical—and about that I’m still not sure—it tells me that consciousness is primary to the physical universe. In fact, it precedes it.”

What Don Hoffman is concluding mathematically, Jesse arrived at via the psilocybin mushroom. He is the founder of the Council on Spiritual Practices, “a collaboration among spiritual guides, experts in the behavioral and biomedical sciences, and scholars of religion, dedicated to making direct experience of the sacred more available to more people.”

A recurring theme throughout the book is the question whether experiences while under the influence of psychedelics are indeed a glimpse through the doors of perception, or merely a delusion created entirely by a drugged brain.

Bill Richards, a Baltimore psychologist, doesn’t believe that they are delusions. He:

“emerged from those first psychedelic explorations in possession of three unshakable convictions. The first is that the experience of the sacred reported both by the great mystics and by people on high-dose psychedelic journeys is the same experience and is “real”—that is, not just a figment of the imagination. “You go deep enough or far out enough in consciousness and you will bump into the sacred. It’s not something we generate; it’s something out there waiting to be discovered. And this reliably happens to nonbelievers as well as believers.” Second, that, whether occasioned by drugs or other means, these experiences of mystical consciousness are in all likelihood the primal basis of religion. And third, that consciousness is a property of the universe, not brains.”

Mycologist Paul Stamets believes that the promise of such insights is in fact a way that the plant kingdom reaches out to humans to invite us to be better stewards:

“Plants and mushrooms have intelligence, and they want us to take care of the environment, and so they communicate that to us in a way we can understand.” Why us? “We humans are the most populous bipedal organisms walking around, so some plants and fungi are especially interested in enlisting our support. I think they have a consciousness and are constantly trying to direct our evolution by speaking out to us biochemically. We just need to be better listeners.”

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859)

Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859)Stamets is, in a sense, echoing the words of the 18th/19th century polymath and naturalist, Alexander von Humboldt, who according to Pollan:

“believed it is only with our feelings, our senses, and our imaginations—that is, with the faculties of human subjectivity—that we can ever penetrate nature’s secrets. “Nature everywhere speaks to man in a voice” that is “familiar to his soul.” There is an order and beauty organizing the system of nature… but it would never have revealed itself to us if not for the human imagination, which is itself of course a product of nature, of the very system it allows us to comprehend.””

The author and spiritual seeker Aldous Huxley had already written The Doors of Perception, based on his experience with mezcaline in 1953, when Al Hubbard introduced him to LSD in 1955. The experience put the author’s earlier trip in the shade.

“As Huxley wrote to Osmond in its aftermath, “What came through the closed door was the realization … the direct, total awareness, from the inside, so to say, of Love as the primary and fundamental cosmic fact.””

After his own, initially tentative, experiences with psychedelics, Pollan concludes that:

“When Huxley speaks of the mind’s “reducing valve”—the faculty that eliminates as much of the world from our conscious awareness as it lets in—he is talking about the ego. That stingy, vigilant security guard admits only the narrowest bandwidth of reality, “a measly trickle of the kind of consciousness which will help us to stay alive.” It’s really good at performing all those activities that natural selection values: getting ahead, getting liked and loved, getting fed, getting laid. Keeping us on task, it is a ferocious editor of anything that might distract us from the work at hand, whether that means regulating our access to memories and strong emotions from within or news of the world without.”

In other words, with the ego out of the picture, the mind is able to explore the expansive realms of truth, beauty, and love. This might remind you of the experience of the neuroanatomist, Jill Bolte Taylor, while she was suffering a catastrophic stroke that shut down her narrowly-focused left hemisphere, leaving her right hemisphere to experience with awe the interconnectedness of everything (I write about it here).

“In the absence of my left hemisphere’s analytical judgment, I was completely entranced by the feelings of tranquillity, safety, blessedness, euphoria, and omniscience.”

Pollan reflects on his three psychedelic experiences, in words reminiscent of Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo’s description of our ignorance of our own true nature:

Pollan reflects on his three psychedelic experiences, in words reminiscent of Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo’s description of our ignorance of our own true nature:

“The journeys have shown me what the Buddhists try to tell us but I have never really understood: that there is much more to consciousness than the ego, as we would see if it would just shut up. And that its dissolution (or transcendence) is nothing to fear; in fact, it is a prerequisite for making any spiritual progress. But the ego, that inner neurotic who insists on running the mental show, is wily and doesn’t relinquish its power without a struggle. Deeming itself indispensable, it will battle against its diminishment, whether in advance or in the middle of the journey. I suspect that’s exactly what mine was up to all through the sleepless nights that preceded each of my trips, striving to convince me that I was risking everything, when really all I was putting at risk was its sovereignty.”

This may also explain why psychedelics have been tremendously helpful for many people who have received a terminal diagnosis, and are suffering depression at the prospect of their own demise. Pollan suggests that these feelings are the product of the ego, desperate to prevent its extinction. When the dying person attains a glimpse of the bigger picture, the existential dread drops right away.

“This sense of merging into some larger totality is of course one of the hallmarks of the mystical experience; our sense of individuality and separateness hinges on a bounded self and a clear demarcation between subject and object. But all that may be a mental construction, a kind of illusion—just as the Buddhists have been trying to tell us. The psychedelic experience of “non-duality” suggests that consciousness survives the disappearance of the self, that it is not so indispensable as we—and it—like to think.”

So, back to the overthrowing of the established order (and could this be the primary reason why, in the US at least, psychedelics were demonised and outlawed around at the end of the 60s?), Pollan suggests that the slang name for LSD may be particularly apt:

“LSD truly was an acid, dissolving almost everything with which it came into contact, beginning with the hierarchies of the mind (the superego, ego, and unconscious) and going on from there to society’s various structures of authority and then to lines of every imaginable kind: between patient and therapist, research and recreation, sickness and health, self and other, subject and object, the spiritual and the material. If all such lines are manifestations of the Apollonian strain in Western civilization, the impulse that erects distinctions, dualities, and hierarchies and defends them, then psychedelics represented the ungovernable Dionysian force that blithely washes all those lines away.”

In other words, could humans pollute nature, or go to war, or exploit the Global South, or rape, murder, or dominate any other being if to do so felt like we were doing it to ourselves?

I’ve just started to read Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm, by Stephen Harrod Buhner, which dovetails very nicely with How To Change Your Mind. Echoing what Pollan writes, he suggests:

I’ve just started to read Plant Intelligence and the Imaginal Realm, by Stephen Harrod Buhner, which dovetails very nicely with How To Change Your Mind. Echoing what Pollan writes, he suggests:

“For if we should recapture the response of the heart to what is presented to the senses, go below the surface of sensory inputs to what is held inside them, touch again the “metaphysical background” that expresses them, we would begin to experience, once more, the world as it really is: alive, aware, interactive, communicative, filled with soul, and very, very intelligent—and we, only one tiny part of that vast scenario. And that would endanger the foundations upon which Western culture, our technology—and all reductionist science—is based; for as James Hillman so eloquently put it, “It was only when science convinced us that nature was dead that it could begin its autopsy in earnest.” A living, aware, and soul-filled world does not respond well to autopsy.”

But how are we to get ourselves out of our enculturated hall of mirrors? How do we think thoughts, and feel feelings, that have been deeply trained out of us?

“What is really true is that we must abandon the normal channels of thought we, as a species, have used the past century or more, step outside of our habituation of perspective, and enter new territory. Not just put our toe in the water, but immerse our whole being, our whole mind and spirit in a very different paradigm and perceptual experience. This means that You must abandon your preconceptions and travel into the world itself, as it really is, and find out for yourself what is true, and find, as well, just what you, yourself, are meant to do in this lifetime. And to do that, to really see deeply into the world, means using perceptual capacities that our culture habitually denies.”

As to how to do that… I’m only up to page 40, so I will have to get back to you on that. Consider this a cliffhanger – so stay tuned!

Other Stuff:

We conducted our first live TEDxStroudWomen webinar last night, when I interviewed our special guests Liu Batchelor of TEDxFolkestone, and Thibau Grumett of TEDxPCL about how to organise and curate a TEDx event. If you missed it, we will be posting the video shortly. Please sign up for our mailing list and/or our social media channels at https://www.tedxstroudwomen.co.uk/ for this and other updates as we prepare for our event, postponed from last month due to the coronavirus, but coming back bigger and better in Spring 2021!

November 25, 2020

Magic, Mystery and Everyday Miracles

“And above all, watch with glittering eyes the whole world around you because the greatest secrets are always hidden in the most unlikely places. Those who don’t believe in magic will never find it.”

― Roald Dahl

“Do you believe in magic?”

A friend asked me this question earlier this year, and my immediate response was that yes, I do believe in magic, in the sense that there are events, feelings, connections and coincidences that happen that we can’t explain. And it seems that the more attention I pay to those things, and give gratitude for them, the more they happen.

It’s possible that one day there will be a scientific explanation for this kind of magic – maybe something to do with quantum entanglement, or the underlying nature of reality, or wormholes through time. But I think it would be a shame to know exactly why and how magic works. Quite literally, the magic would be lost.

So I try not to examine it too closely, in case I break the spell.

I only discovered this kind of everyday magic about 17 years ago, around the time I went to Peru, which was in itself a magical experience, and I feel like my life has been touched by magic ever since. I had just read The Celestine Prophecy, by James Redfield, a spiritual novel that proposes that there is no such thing as coincidence, that every event and encounter has significance if we are only willing to see it. It’s too long a story to relate here, but even the path of synchronicities that led me to Peru was magical in itself, and things got even more crazy-magical once I got there (including an extraordinary night when I found myself in the main square of Cuzco watching a lunar eclipse with Tony Hadley of Spandau Ballet – and no, I wasn’t on drugs – although copious quantities of Chilean Sauvignon Blanc were involved…).

Tony and me, Cuzco (2003)

Tony and me, Cuzco (2003)I suppose that whether or not you claim to believe in magic depends on how you define it. If you picture Harry Potter-style wand-waving, then no, I don’t believe in it. But I wouldn’t want the kind of magic that leads to instant gratification. This was, in fact, my friend’s next question:

“What would you do if you were gifted with a magic wand?”

This question had me baffled for a while. At first I thought I should say something lofty, like “world peace”. But we all know that if we had world peace on a Tuesday, humans would have found something to fall out about by lunchtime on Wednesday.

So then I tried to think of something more personal – financial security, owning a house and garden, wishing for good things for my mother or my friends – but that all seemed too prosaic.

And eventually I realised that if I did have a magic wand, I would put it in a nice glass cabinet and admire it, and know I had the power to use it if I really needed it one day, but I would leave it untouched for now. Three reasons:

1. If it was for me to decide what was worthy of my one wish, I would probably come up with something too small. My best ever idea wasn’t my idea at all. The notion to row across oceans came from somewhere else, for sure, and was far more audacious than anything I could have come up with. I felt as if I’d been called to adventure. The collective intelligence of the universe is much greater than mine. My job is simply to recognise the call when I hear it, and to say “yes”.

2. I believe life is really about the journey. When I did the obituary exercise that changed my life, I found out that I wanted to live many different lifetimes in one, to live as rich and varied a life as possible. So it’s not about a result I want to “have”, or even something I want to “do”, it’s about a way I want to “be”, and that has to unfold in its own way, with all its ups and downs, snakes and ladders.

Would it have felt this good if I’d just waved a magic wand? I doubt it.

Would it have felt this good if I’d just waved a magic wand? I doubt it.Following up on that last point, when I was on the Atlantic, and having a really, really hard time, I wanted nothing more than to reach Antigua. If I’d had a magic wand, I might have been tempted to use it. But then when I look at the video of me finally arriving after 103 days at sea, and remember how utterly euphoric I felt, I know the sense of satisfaction – and the learning – wouldn’t have been as great if I’d taken the shortcut by magicking myself there.

3. The suspense is so much fun! If I could wave the magic wand, it would be like skipping to the last chapter of a book. The “not knowing” is such a deliciously enticing stage of the story. Even if you think you know the eventual outcome, there are lots of times when you don’t know if or how you’re going to get there. Hope and doubt, optimism and pessimism… even elation and despair. The magic wand would take all of that away. Imagine the romcom where the guy gets the girl (or the girl gets the guy, or the guy gets the guy, or the girl gets the girl) in the first scene. No flirtation, no misunderstandings, no “will they, won’t they?”. Where would be the fun in that?

So, in summary, magic wands are highly overrated. But magic… that is something wonderful. And it’s all around us, all the time, if we just choose to see it.

[And lest we forget, to someone alive a thousand years ago, our current lifestyles would appear magical in the extreme. Electric lights, TVs, computers and mobile phones are, of course, pretty damn magical, but even the fact that ordinary people (in the developed world, at least) can simply buy whatever they want in the way of food, clothes, and books, and have hot and cold water literally on tap, would blow the mind of a time traveller from 1020.]

For more on magic, here are two beautiful books that I highly recommend – I listened to them both on audiobook:

The Enchanted Life: Unlocking the Magic of the Everyday, by Sharon Blackie

Spun Into Gold: The Secret Life of a Female Magician, by Romany Romany

Other Stuff:

Happy Thanksgiving!

Yes, I know we don’t do Thanksgiving in the UK, but in 2020 it seems more important than ever to focus on the things we can be grateful for, rather than the myriad of things that have not gone quite as we hoped.

On that note, a reminder that TEDxStroudWomen will NOT be taking place this coming Sunday, 29th November, as we had planned, due to the current COVID restrictions. I have applied for a new TEDx license, and we will hold our rescheduled event in the spring – I will update you as soon as I have any definite news.

Meanwhile, we have a wonderful series of FREE webinars for your delectation, on the theme of what goes into creating a TEDx event, kicking off next Wednesday with me in conversation with two TEDx organisers who have trodden this path before me. Liu Batchelor has curated TEDxFolkestone for several years, always in real life. Thibau Grumett curated his first TEDx this year, in virtual format. I look forward to learning from their contrasting experiences, and hope you will join us by registering below – and please forward this email to any aspiring TEDxers who might be interested!

November 19, 2020

Cycles and Spirals

Seems we humans like to represent ideas as cycles, or spirals. In fact, even the things that at first appear to be cycles are really spirals – the seasons form a cycle, but winter 2021 will not be the same as winter 2020 (thank heavens, some might say…). Time moves on, so in the same way you can’t step in the same river twice, you can’t live through the same winter twice.

Here are a few cycles for your delectation, including one I made up myself.

The Hero’s Journey, as described by Joseph Campbell:

The hero isn’t a hero when he sets out, but as he crosses the threshold into the unknown, and endures trials, failures, and the innermost cave, he grows as a person before returning transformed, bearing a gift of wisdom for his community. Star Wars famously follows this structure, and it’s no coincidence that George Lucas was good friends with Joseph Campbell.

And then the cycle starts over again. As did Star Wars in its 8 reboots.

The Rise and Fall of Empires:

I’ve written before about Glubb and Ophuls and their perspectives on the rise and fall of empires. Glubb, in particular, asserted that the average lifespan of an empire is around 250 years.

Some people have tracked this to the movements of Pluto. I think the correlation is a bit of a stretch, frankly, but it does at least illustrate our human affinity for cycles. According to this theory, the United States of America is heading for imminent collapse…. but take it from me, as someone who lives in a supposedly post-collapse country, it’s not so bad. We get by.

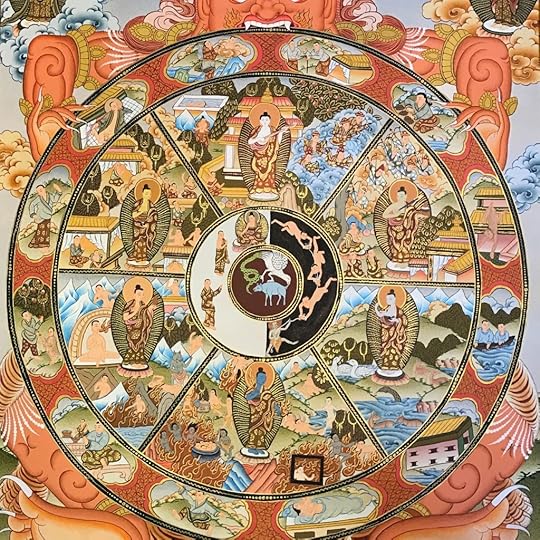

The Buddhist Wheel of Life:

When I was interviewing Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo for my book, The Gifts of Solitude, she shared with me something tht has stayed with me ever since. She said:

“…the [Buddhist] Wheel of Life… [is] like a wheel which is endlessly turning, called samsara [Note: Samsara in Buddhism is the continuous cycle of life, death, and reincarnation] … At the hub of the wheel are three animals – a pig, a rooster, and a snake. The snake stands for anger, the rooster for desire and greed, and the pig for ignorance. And they’re biting each other’s tails… And their going round and round and round is what sets the whole wheel spinning. And that’s the problem. Our delusion about our true nature, which gives rise to greed and desire for what gives pleasure, and aversion and anger towards that which does not give pleasure. And it keeps the whole wheel circling, no matter our best intentions. So the only way to stop the wheel is to break the hub… Within those three, the important one is our ignorance, our ignorance of our true nature. We identify with our ego, and although our ego is a good servant, it’s a terrible master, because it’s blind… Once we realize that the nature of our existence is beyond thought and emotions, that it is incredibly vast and interconnected with all other beings, then the sense of isolation, separation, fear and hopes fall away. It’s a tremendous relief!”

So what do we make of all this? Are cycles/spirals part of the inevitable way of things? Maybe even the entire Universe is caught in an endless cycle of birth and collapse – how can we know that our Big Bang was the only Big Bang?

For now, we’re not in any immediate danger of stopping the wheel, depending as that does on ending human ignorance…

…so maybe the best thing for us to do is adopt an attitude of acceptance.

Day and night, summer and winter, birth and death, rise and fall… it’s all part of the human condition. We tend to cling to what is known and familiar, but sometimes we have to let go of the old to make way for the new, often without yet knowing what the new might be. That can be scary, but is also necessary.

So maybe the cycle isn’t something to be escaped from. What would existence be like if we somehow ended this endless coming and going? As I sit here typing this, I think about my breath, coming and going. If it stopped coming and going I’d be in pretty poor shape. So maybe cycles of change, like the cycles of my breathing, are essential to life.

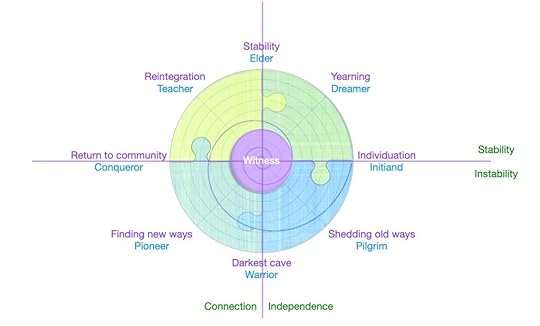

So here is my version of a cycle:

The graphic is intended to be read both sequentially as a clockwise cycle, and also as four complementary pairs with the archetype on the opposite side of the circle. It aims to summarise the spiralling nature of human existence, at both the individual and the collective level, to remind us that disruption and struggle are part of the natural cycle of things, and that letting go of the old is an inevitable and unavoidable step on the way to creating the new.

But we don’t have to get caught up in the drama. We can be the eye of the storm, the calm witness to the wheel as it spins around us, not getting over-excited about the “good” stuff nor over-despondent about the “bad”.

Change is the only constant. So we may as well get used to it.

November 12, 2020

Braiding Sweetgrass, Kiss the Ground, and Other Hints of Hope

Eco-warriors sometimes get exhausted. Often, it seems that there is too much bad news, and not enough good. And even the silver clouds, such as the election of an eco-sympathetic US president, can have dark linings.

So I’d like to share a book and a documentary that I have read and seen recently that cheered me up, and might offer balm to the battle-weary green soul.

I listened to the author, Robin Wall Kimmerer, reading the audiobook of Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants. She reads as beautifully as she writes, and you can often hear the smile in her voice as she describes her favourite wonders of nature. She is a member of the Potawatomi Nation, and also a professional botanist, and she brings these two traditions together, each enhancing the other.

The main message that I took away from the book is that, while we might sometimes think that humans are the worst thing that ever happened to the rest of the natural world, this is not true. We are part of nature, and when we choose to live harmoniously and respectfully it, this can benefit nature as much as it benefits us.

The main message that I took away from the book is that, while we might sometimes think that humans are the worst thing that ever happened to the rest of the natural world, this is not true. We are part of nature, and when we choose to live harmoniously and respectfully it, this can benefit nature as much as it benefits us.

For example, Robin-the-botanist participates in a scientific study to assess the impacts of harvesting sweetgrass. Plots of grass are designated for indigenous-style harvesting, while control plots are left to their own devices. Spoiler alert! The respectfully-harvested plots become healthier than the left-alone plots.

Key to this is the concept of the indigenous “honourable harvest”, which can be summed up:

“Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them.

Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life. Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer.

Never take the first. Never take the last. Take only what you need.

Take only that which is given.

Never take more than half. Leave some for others. Harvest in a way that minimizes harm.

Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken. Share.

Give thanks for what you have been given.

Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken.

Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

In the absence of such honour and respect, modern civilisation has become like the Windigo, the insatiable monster of indigenous tradition. The more it consumes, the hungrier it becomes. Enough is never enough.

“The footprints of the Windigo [are] everywhere you look. They stomp in the industrial sludge of Onondaga Lake. And over a savagely clear-cut slope in the Oregon Coast Range where the earth is slumping into the river. You can see them where coal mines rip off mountaintops in West Virginia and in oil-slick footprints on the beaches of the Gulf of Mexico. A square mile of industrial soybeans. A diamond mine in Rwanda. A closet stuffed with clothes. Windigo footprints all, they are the tracks of insatiable consumption. So many have been bitten. You can see them walking the malls, eying your farm for a housing development, running for Congress. We are all complicit. We’ve allowed the “market” to define what we value so that the redefined common good seems to depend on profligate lifestyles that enrich the sellers while impoverishing the soul and the earth. Cautionary Windigo tales arose in a commons-based society where sharing was essential to survival and greed made any individual a danger to the whole. In the old times, individuals who endangered the community by taking too much for themselves were first counselled, then ostracized, and if the greed continued, they were eventually banished.”

This disconnection doesn’t just damage the Earth – it damages us, as our imagined dislocation leaves us feeling vulnerable and fearful.

Robin Wall Kimmerer

“Philosophers call this state of isolation and disconnection “species loneliness”—a deep, unnamed sadness stemming from estrangement from the rest of Creation, from the loss of relationship. As our human dominance of the world has grown, we have become more isolated, more lonely when we can no longer call out to our neighbors.”

“It is a terrible punishment to be banished from the web of reciprocity, with no one to share with you and no one for you to care for.”

My favourite phrase in the book is “Regenerative Reciprocity”: when we remember who we are, and our relationship with our living, breathing planet, our attitude changes from one of rapaciousness to one of gratitude, and we start acting in very different ways. No matter how urban or technologically-mediated our lives are, this understanding is available to all of us – and it isn’t just good for the Earth, it is good for our emotional wellbeing:

“Each of us comes from people who were once indigenous. We can reclaim our membership in the cultures of gratitude that formed our old relationships with the living earth. Gratitude is a powerful antidote to Windigo psychosis. A deep awareness of the gifts of the earth and of each other is medicine. The practice of gratitude lets us hear the badgering of marketers as the stomach grumblings of a Windigo. It celebrates cultures of regenerative reciprocity, where wealth is understood to be having enough to share and riches are counted in mutually beneficial relationships. Besides, it makes us happy.”

When I walk in the lovely countryside near my home, it makes me feel sad when I hear birds raising the alarm with their cries or the exaggeratedly loud beat of their wings, and when deer and rabbits go running at my approach. I can’t blame them – as Yuval Noah Harari points out in Sapiens, as the population of homo sapiens spread across the globe, there was a strong correlation between our arrival and the extinction of megafauna from each continent. It seems we were the likely perpetrator, as well as killing off the other five species of humans that used to share our planet. So running off seems like an eminently sensible survival strategy when there is a homo sapiens in the vicinity.

Could it ever become different? I would like to think so. Wall Kimmer paints a beautiful vision:

“We need acts of restoration, not only for polluted waters and degraded lands, but also for our relationship to the world. We need to restore honor to the way we live, so that when we walk through the world we don’t have to avert our eyes with shame, so that we can hold our heads up high and receive the respectful acknowledgment of the rest of the earth’s beings.”

Coming back down to earth – literally – I also recommend Kiss the Ground (trailer here, full movie available on Netflix or Vimeo – or you can host your own screening). Narrated by Woody Harrelson, with celebrity appearances from Patricia Arquette, Gisele Bundchen, and Ian Somerhalder, as well as farmers, ranchers, scientists, and Paul Hawken, the author of Drawdown, the film focuses on how we produce our food, and the implications for soil health.

Coming back down to earth – literally – I also recommend Kiss the Ground (trailer here, full movie available on Netflix or Vimeo – or you can host your own screening). Narrated by Woody Harrelson, with celebrity appearances from Patricia Arquette, Gisele Bundchen, and Ian Somerhalder, as well as farmers, ranchers, scientists, and Paul Hawken, the author of Drawdown, the film focuses on how we produce our food, and the implications for soil health.

The bad news is that, in the US at least, the soil has become so depleted by industrial agriculture that it will only be able to produce 50 or 60 more harvests (yes, that is 50 or 60 more years of food production) before the topsoil is so eroded and/or denatured that agriculture collapses.

The good news is that soil regeneration can be simple, cheap, and enormously effective not just in improving the soil for future generations, but the revitalised vegetation also draws down CO2 into the ground through biosequestration to help mitigate climate change. The images towards the end of the film of the transformation of 35,000 square kilometres of the Loess Plateau in China are particularly dramatic. The film focuses mostly on farmers and large-scale projects, but these are principles we can apply at the domestic level of food production too (such as never leaving soil bare, but always having a cover crop), and we can also choose to support food producers who farm regeneratively.

Healthier plants, healthier humans, happier cattle, regenerated soil, and mitigated climate change. What’s not to love about that? That’s regenerative reciprocity in action!

Other Stuff:

Due to the lockdown in England, we’ve had to postpone TEDxStroudWomen until the spring. As the organising committee, we are of course disappointed to have to change our plans, but we also trust that it will be well worth the wait, and will be even bigger and better in March 2021! All tickets are valid for the rescheduled date, and we thank you for your patience.

On Tuesday, 17th November (that’s next Tuesday) I will be speaking at the WeWorld Summit 2020: Luminate. As well as salty old sea stories of ocean rowing, I will also be sharing some insights from my recent doctoral thesis for the first time in public, so do please join me, WeWorld founder Dr Rain Lim, and the other speakers for this exciting summit!

October 30, 2020

The Ocean in a Drop

There has been this assumption, on the wing of the liberal, sustainable, equitable, political left, that we will win because we think we are right. This assumption is clearly not working. So then we wonder – should we use the same strategies that are working so well for what we regard as the conservative, exploitative, unequal, political right? – because apparently they are winning.

No. We should not.

This judgement, this “othering”, this polarisation, can never succeed. We have to recognise that we are all, individually and collectively, all of it. Everything is connected. I am you, and you are me. We are them, and they are us. We are all inseparable, all aspects of the one interconnected web of being.

While we imagine separation, we are doomed. When we envisage connection, we may yet survive.

Personally, I don’t believe this is a moral universe. During the hundreds of days and nights I spent on the ocean, I had no sense of it being benevolent, malevolent, or even indifferent. These words anthropomorphise the ocean, and even if it turns out that the ocean has some form of consciousness, I don’t believe that it has morality, nor any opinion about what happens to those who dare to venture across its waters.

My view is that the law of the cosmos is not moral law; it is scientific law. Even if I did believe that the arc of the moral universe tends towards justice, to quote Martin Luther King Jr., whose justice would that be? Who gets to decide? (Cue a Game of Thrones moment, when Daenerys Targaryen claims the right to decide what is good, and the others don’t get to choose – leading Jon Snow to come to his own decision…)

My view is that the law of the cosmos is not moral law; it is scientific law. Even if I did believe that the arc of the moral universe tends towards justice, to quote Martin Luther King Jr., whose justice would that be? Who gets to decide? (Cue a Game of Thrones moment, when Daenerys Targaryen claims the right to decide what is good, and the others don’t get to choose – leading Jon Snow to come to his own decision…)

This, I believe, is the point of free will. Sam Harris and others might argue that free will does not exist, but as the saying goes, even if we don’t have free will, we have free won’t, i.e. ideas suggest themselves to us based on our experiences and conditioning, and we choose from the options available. I am good, and I am evil; I contain both polarities, but I can make conscious choices about which pole I express. It is the consciousness that we bring to it – if we accept the responsibility of being conscious beings – that determines what the future holds.

In a recent newsletter from the Centre for Action and Contemplation, the mystic and Episcopal priest, Cynthia Bourgeault, quotes the final poem from Thomas Keating’s The Secret Embrace, “What Matters”:

“Only the Divine matters,

And because the Divine matters,

Everything matters.”

She describes this as “a powerful new incentive for a compassionate re-engagement with our times”, and goes on to comment:

“In this short poem of eleven laser-like words, Thomas smashes through centuries of theological barricades separating God from the world and contemplation from action, offering instead a flowing vision of oneness within a profoundly interwoven and responsive relational field… Practically speaking, the map affirms that our actions, our choices, our connections bear more weight than we dare to believe. We are neither isolated nor helpless but immersed in a great web of belonging in which divine intelligence and compassion are always at our disposal if our courage does not fail us.” [her italics]

So this is what it comes down to. How much power do you have, or do I have, to make a difference in the world?

More than we think. And getting some kind of accurate understanding about the extent of our power is really, really important.

I hinted at this in my blog post a couple of weeks ago. And a couple of weeks before that.

If consciousness is fractal, then anything I (or you) think, say, or do, has an impact. Imagine a single drop of ink falling into the ocean. It won’t change the colour of the ocean a lot, but it will change it an infinitesimal amount. Everything we do makes a difference. What kind of difference are you making?

It’s one of life’s challenges to understand where the boundary lies between what we can control or influence, and what we can’t. If we try to control things that are actually beyond our control (like Covid), we get frustrated.

But if we don’t control or influence the things that we can, then we’re being unnecessarily helpless, a bystander to our own lives. As Jim Rohn says, “If you don’t design your own life plan, chances are you’ll fall into someone else’s plan.”

So how do we get this right? How do we know where the boundary lies?

For better or worse, believe that you have a lot more power than you think you have. Our world is now so interconnected that we never know what impacts we have. A good starting assumption is, as Scott Page says, “An actor in a complex system controls almost nothing, yet influences almost everything.” Plan accordingly. Impeccability is a very high standard, and none of us will reach it, but we can try.

Marianne Williamson’s most famous quote hints that we know, on a deep level, just how powerful we are, but too often we choose to play small, because our power scares us:

“Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, and fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people will not feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It is not just in some of us; it is in everyone and as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give others permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.”

So try that idea on for size. I hope you find it empowering, rather than paralysing. Interesting times are already here, with many more ahead, so it behooves us all to be everything we can be.

October 29, 2020

What is it you Plan to Do with your One Wild and Precious Life?

I’ve written before about life purpose, as finding a sense of purpose has made such a massive difference to my life, helping me to discover and unleash capabilities I didn’t know I had.

But how do we find a sense of purpose? If we don’t have a clue what our purpose is, where do we start looking? Or maybe we could pick any one of half a dozen purposes – how do we figure out which one is The One?

First, I don’t think we need to stress too much about this. For most of us, and certainly for me, I don’t think there is just one single purpose for an entire lifetime. Purpose is likely to evolve, or even change completely, according to our age and circumstances.

Mary Wesley

Mary WesleySecond, purpose doesn’t have to look like a grand obsession with music, science, exploration, etc. Purpose can be a quiet creature, more values-based, being more about how we do what we do that what we are actually doing.

And third, purpose might just come and find you when it’s good and ready – which of course, might mean when you are good and ready. Sometimes we find it, and sometimes it finds us. I always take great comfort from the example of Mary Wesley, who didn’t publish her first novel until she was 71 years old, and still managed to rack up 10 bestsellers and 3 million copies sold before she died at the age of 90.

Having said all that, I’d like to offer a couple of pointers to rebels looking for a cause.

The Obituary Exercise

I have written and spoken about this countless times, but there’s a good reason for that. It works. It reminds you that you don’t have forever (Mary Wesley notwithstanding) to create the life you want. And because it begins with the end in mind, and invites you to reverse-engineer from there, it frees your imagination from the tyranny of “what am I qualified for?” So try it. Described here.

What is the Sunshine?

This is for those of you who have multiple contenders vying to be your purpose.

Back in 2004, it was my sudden awareness of the environmental crisis that first gave me a sense of mission and purpose. However, as time went on, other important issues came to my attention which seemed to be connected to, but not the same as, the environmental mission. Well-meaning friends and colleagues advised me to pick one, and focus on it, but as soon as I tried to, I discovered it was connected to all the others. It seemed impossible to fix any one problem in isolation, because it rapidly became clear it was part of a whole ecosystem of interconnected issues.

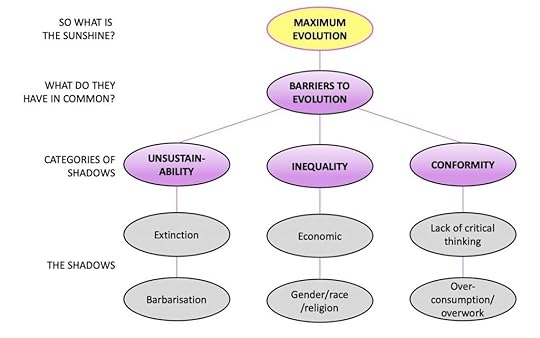

My solution was to map out all the issues that bugged me, group them together under headings, and then ask myself the question: “If these are the shadows, what is the sunshine?” In other words, if these were the things that I did not want, then what did I want? This was the result (to be read from the bottom upwards):

It turned out that what I really cared about was the freedom of humanity (and all other sentient beings) to evolve to its highest potential, and the things that really bothered me were the obstacles impeding this freedom. Clearly our extinction would impede our evolution very seriously, and so would the collapse of civilisation, leading to a barbaric world where we struggle to meet our basic needs. Inequality of any kind affects the freedom of the disadvantaged to become everything that they can be. Having previously been consummately conformist myself, I now found that my own shadow came back to haunt me: I knew from personal experience how easy it is to lie low, fit in, and be agreeable, to the detriment of mind and spirit. I also knew how easy it is to get caught in the salary trap, the rat race, or the hedonic treadmill, whichever phrase resonates most with you – almost (!) as if the capitalist system were designed to prevent us having enough time and space to think, in case we start a revolution against the insanity of it all.

Why evolution? Certainly, Conversations with God, by Neale Donald Walsch, has been a big influence on me.

“The soul has come to the body, and the body to life, for the purpose of evolution. You are evolving, you are becoming. And you are using your relationship with everything to decide what you are becoming. This is the job you came here to do. This is the joy of creating Self. Of knowing Self. Of becoming, consciously, what you wish to be.”

I’m not offering evolution as a one-size-fits-all purpose. I offer it here more as an example of the process, than as a ready-made answer. Every person has to do their own inner work to find their own answer to the question: what am I doing here?

It is vitally important, in my view, that we ask this question. To read that the Gallup poll across 155 countries found that 85% of employees are either “not engaged” or “actively disengaged” is heartbreaking, a tragic waste of human time, creativity, and potential, especially when there is so much important work to be done.

As Steve Jobs said in his famous Stanford commencement speech in 2005:

Steve Jobs at Stanford

“Your work is going to fill a large part of your life and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do… Your time is limited, so don’t waste it living someone else’s life. Don’t be trapped by dogma — which is living with the results of other people’s thinking. Don’t let the noise of others’ opinions drown out your own inner voice. And most important, have the courage to follow your heart and intuition. They somehow already know what you truly want to become. Everything else is secondary.”

Given that he died at the young age of 56 (I’m 52, so 56 seems really young to die), it’s poignant that he mentioned the importance of accepting our mortality if we are to truly live. Paradoxically, recognising the inevitability of death gives meaning to our life:

“Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”

Ultimately, finding purpose is as simple as that. Follow your heart to find what you want to do, and then use your head to figure out how you can do that and pay the bills. But don’t, please, let the bills decide how you’re going to spend the one non-renewable resource – your time.

“Doesn’t everything die at last, and too soon?

Tell me, what is it you plan to do

With your one wild and precious life?”

— The Summer Day, by Mary Oliver

Other Stuff: TEDxStroudWomen

Tickets are available at the early bird price for just two more days for TEDxStroudWomen. £5 for 9 amazing speakers is incredibly good value. Please buy at least one ticket, post, and share!

We’re now listed as an event on LinkedIn, to make it easy to share with your network.

Please note – you don’t have to be near Stroud, and you don’t have to be a woman, to enjoy this event. We are live-streaming on 29th November, and all are welcome!

There’s a great video on LinkedIn of behind-the-scenes clips, along with shots of all our speakers and their topics. I’m so excited to be presenting these wonderful women to the world.

October 22, 2020

Reasons to be Cheerful(ish)

“When we get out of the glass bottles of our ego,

“When we get out of the glass bottles of our ego,

and when we escape like squirrels turning in the

cages of our personality

and get into the forests again,

we shall shiver with cold and fright

but things will happen to us

so that we don’t know ourselves.

Cool, unlying life will rush in,

and passion will make our bodies taut with power,

we shall stamp our feet with new power

and old things will fall down,

we shall laugh, and institutions will curl up like

burnt paper.”

Escape, by D. H. Lawrence

Regular readers of this blog will know that I believe we’re in for a rough ride over the next few years (or maybe even decades) as we transition from the old industrial order to a new way of being in the world.

The transition is necessary, but that doesn’t mean it will be easy.

To recap, according to the analyses of Sir John Glubb and William Ophuls, it is likely that the globalised world is entering an era of major civilisational disruption, or even collapse. Humanity has created a perfect storm of “wicked” problems that are interconnected and constantly evolving, reinforced by mutually reinforcing positive feedback loops: for example, climate change, ocean acidification, biodiversity loss, soil exhaustion, overpopulation, economic inequality, and political isolationism, which combine with various quirks of human psychology to blind us to the scale and urgency of the problems until it is now probably too late, given the time lags inherent in the system.