Roz Savage's Blog, page 15

April 2, 2020

A Good Time for a Life Redesign

“How we spend our days is how we spend our lives.” — Annie Dillard

Routines can help us hold it all together. When everything is in turmoil, and life is scary, putting certain habits in place can help create a sense of order, and ground us when we’re feeling untethered. So if your routine has been thrown into disarray by coronavirus, it’s possible to see it as opportunity rather than embuggeration.

As with everything I’ve learned in this lifetime, I learned this the hard way. When I first set out across the Atlantic, within a matter of hours the excitement of the departure had evaporated, and I crashed into a state of complete overwhelm. I actually felt rather foolish. I had desperately wanted this adventure, and now I hated it. It was just so damn hard. Even something as simple as boiling water to rehydrate my freeze-dried dinner took ages — to get out all the equipment I needed, fire up the camping stove, put the powdery food in my thermos pot without the wind blowing it all over me, pour the boiling water into the pot without scalding myself, all while the boat pitched and rolled, and waves crashed over the deck.

I fell into a slump. I started skipping rowing shifts. After all, there was nobody to see, and I had three thousand miles to go — I could always make up for it later.

Running the Algorithm of Personal Pride

But then I noticed that any benefit I got from snoozing my way through a rowing shift was more than outweighed by how disappointed I felt with myself. Even though there was nobody there to see me, I was there to see me, and this wasn’t the person I wanted to be.

So I got my act together. I decided I was going to do four shifts of three hours of rowing, no matter whether I felt like it or not. I was going to stick to this routine like my life depended on it — which, in a way, it did. If I didn’t get to the other side of the ocean in a hundred days or so, I would run out of food.

From that point on, the schedule was non-negotiable. And far from being a tyranny, it was a complete sanity-saver. Until then, I’d often felt like I had an angel on one shoulder, piously telling me I should row, while I had a devil on the other shoulder, whispering to me that I was tired, that my shoulders hurt, that skipping just one little rowing shift wouldn’t matter in the overall scheme of things. Once I’d made the commitment to the rowing routine, they both shut up, which was a huge relief.

Routinise What Needs To Be Done

It saves so much mental energy to routinise things that need to get done. All that constant negotiating with myself was exhausting — the indecision, the dithering, the guilt and shame. That’s not what I wanted going on in my head all the time. I had to make it a central plank of my identity that I was the kind of person who shows up and gets the job done. (And, as a huge added bonus, having a routine also means that when you’re not working you have a clear conscience. It’s essential for your mental health for time off to be psychological as well as physical.)

This isn’t the end of the article!

It is an excerpt from my forthcoming book, The Gifts of Solitude. I would be most grateful if you would go to the full article on Medium.com, which will earn me a few cents in these financially challenging times. If you follow this “friend link“, you don’t have to pay to read it. I believe the algorithm gauges the number of people who read it, and for how many minutes, so please read slowly!

Please also check out my new videos and podcasts at the Gifts of Solitude website. Enjoy!

And thank you.

March 31, 2020

Words of Wisdom from a Buddhist Nun in Times of Coronavirus

This is an excerpt from my forthcoming book, The Gifts of Solitude. This is just the introduction to the interview with Tenzin Palmo – for the interview itself, I would be most grateful if you would go to the full article on Medium.com, which will earn me a few cents in these financially challenging times. If you follow this “friend link“, you don’t have to pay to read it.

I talk to Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo over Zoom on a Monday morning and I am rather dishevelled, my hair still damp from the shower, feeling rather below par after a weekend in which the days were spent writing, the nights tossing and turning with coronavirus-related money worries.

The Zoom connection is swiftly made, the internet bandwidth from the nunnery she founded in northern India giving us a clear connection, albeit with a slight time lag that will lead to me occasionally speak over her by mistake. She looks robust, healthy and serene – the exact opposite of how I feel. She is sitting in front of a white wall bearing a colourful banner of a Tibetan deity. When she flashes her smile, which is infrequent but broad and dazzling, it reminds me of somebody. It is only later than I place it – Cameron Diaz, if Cameron Diaz were a shaven-headed, seventy-six year-old Buddhist nun from Bethnal Green.

It was early 2004 when I first read the book about Tenzin Palmo’s life, Cave in the Snow. It had been recommended by a friend I’d met while traveling in Peru. He said there was this amazing book about a British nun who had spent twelve years meditating alone in a cave in the Himalayas. I said it sounded really boring.

It was early 2004 when I first read the book about Tenzin Palmo’s life, Cave in the Snow. It had been recommended by a friend I’d met while traveling in Peru. He said there was this amazing book about a British nun who had spent twelve years meditating alone in a cave in the Himalayas. I said it sounded really boring.

But then I read it, and found an amazing story of a brave, pioneering woman who boldly aspired to attain enlightenment while incarnated in a female body. This mission would involve not only unwavering dedication to her spiritual path, but doggedly ploughing her way through the institutionalised sexism and misogyny of organised religion.

I can’t do justice to her full story here, and urge you to read the book, but to give you an extremely potted biography: Diane Perry was born in 1943, and realised she was a Buddhist at the age of eighteen when she read The Mind Unshaken, by John Walters, which finally provided answers to the questions she had about herself and about life. Aged twenty-one, she travelled to India and was ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist monastic, taking the name Tenzin Palmo. (Jetsunma is a rarely-bestowed honorific title, meaning “Venerable Master”, granted to her in 2008.)

Having diligently pursued her calling in various Indian monasteries, in 1976 she felt called to find a more ascetic location for her meditation practice, and found a small cave – really more of a rocky overhang – in a remote location in the Himalayas, 13,200 feet above sea level, well above the snowline. They built out a wall to enlarge and protect the cave, but it was still tiny.

Life was harsh. She grew her own vegetables (she is a huge fan of the humble turnip), and in the summer supplies were delivered from a nearby village, although they didn’t always arrive. In the winter the snow prevented access, so she relied on stockpiles. Temperatures were often below minus thirty degrees. Once her cave was completely buried in snow, and she had to dig her way out with a saucepan lid. She meditated for twelve hours a day in a meditation box. She slept in it too, sitting upright.

The cave was her home for twelve years, from the age of 33 to 45. For the first nine years, she made occasional trips away or had visitors, but for the last three she was on strict retreat, with no human contact.

So she knows a thing or two about solitude.

When I started writing this book about solitude, Tenzin Palmo immediately came to mind. Without her inspiration, I don’t believe I would have set out to row across oceans. In my own, very different, way, I hoped that my solitude on the ocean might lead to, if not enlightenment, at least to some greater understanding of myself, life, and the nature of reality. I often thought of her as I was rowing, especially to inspire me when I was feeling sorry for myself.

In preparation for our interview, I had revisited Cave in the Snow, this time listening to it as an audiobook, and had discovered new layers of meaning which made sense only now, after my own experiences of solitude. It had also struck me anew what an exceptional story – indeed, what an exceptional woman – this was.

And now I was talking to her.

I confessed to feeling somewhat starstruck, and found myself babbling. On the recording of our conversation I can hear my usual eloquence caught up in umms and errs, and seem to have developed a new and annoying habit of clicking my tongue on my teeth just before I say something. Tenzin Palmo, meanwhile, is composed, articulate, and wise. I will attempt to do justice to our conversation here, although I have edited for length.

(The recording is available in its entirety, umms, errs, clicks and all, on the Gifts of Solitude website.)

…

A reminder again: for the interview itself, I would be most grateful if you would go to the full article on Medium.com, which will earn me a few cents. If you follow this “friend link“, you don’t have to pay. Thank you!

March 28, 2020

The Fallacy of Future Fears

Not sure you can survive lockdown? Only one way to find out. Here’s how.

We can endure a lot more than we think we can. Take it from me – I have proved this. There were many, many times that I thought I had absolutely reached my limit of frustration, discomfort, pain, boredom, and would surely explode with the unbearableness of it all – and yet, obviously, I didn’t, or I wouldn’t be here writing this.

Human beings are incredibly adaptable, and blessed (or cursed) with short memories. We might fiercely resist change, but once it comes, before long we have forgotten what life was like before. Witness car seatbelts, smoking bans, and lockdowns.

And yet we often try to imagine what we will feel like in an unknown and unknowable future, and decide we don’t like it. I call this the Fallacy of Future Fears.

Several years ago I met a very tall Dutchman called Milko van Gool who was going to swim from Ireland to Scotland, one of seven classic channel swims around the globe. He’s six foot five, I’m five foot four on a good day, so the photo of the two of us together doesn’t quite look like two members of the same species.

I was very struck by a comment that Milko made, that many channel swimmers are defeated, not by jellyfish, cold or currents, not even by exhaustion or pain, but by their fear of what they might experience before the end of the swim. “To fear the things that lie in wait for you is the real killer.”

Imagine that you’re swimming a channel, you’ve been going for six or seven hours, so you’re well into the swim but the end is not yet in sight. The water is a bit rough, and of course you’re extremely tired, but you’ve trained hard and you’re still able to put one stroke in front of another.

But then an unwelcome thought pops into your head.

“Still another three hours of this. I’m tired already, so how will it feel by the end?”

You start to feel weary in anticipation of your own future weariness. Your arms and legs are still swimming but your mind is careening off into the future, worrying about just how tired you might become, wondering if you’ve got what it takes.

I experienced something like this on the Atlantic. I wasted a lot of mental energy in the first half of the voyage wondering, “Do I have what it takes to row an ocean?”

Given that I had never tried to row an ocean before, my mind had no supporting evidence that I could do it, and so when it raked through my memory banks the answer kept coming back – NO. To say that this had a negative impact on my morale would be a serious understatement.

It took me a while to figure out that the question was bogus. The only way that I could find out whether I could do this was to continue doing it. Only when I either reached my destination or quit and asked for a pickup would I know whether I could do it. Until then it was all pointless speculation.

So I stopped focusing on the asking, and started instead to focus on the doing. I stopped freaking myself out by pondering imponderables, and forced myself to keep doing what it takes, namely, slogging my way across the ocean, one oarstroke at a time.

It’s tempting to extrapolate into the future and decide we can’t face it. It’s the brain’s job to keep us safe, so it loves to gallop off into the unknown and project our deepest fears into it. I had to learn to say, “Thank you, brain, for doing such a great job of flagging up all the things that could go wrong. I will do what I can to prepare for them. But I’m also going to remember that these are imaginings, not reality. In the past things have hardly every turned out how I expected them to, and they probably won’t this time either. So let’s stay in the present and simply wait and see what happens.”

And that’s the key – stay present. Simply keep on keeping on. Take it moment to moment, and one day at a time, and eventually you’ll get to the end.

This one technique has made a huge difference to the way I live my life. When I take on a big and intimidating challenge (and I seem to have a nasty habit of doing that – like trying to write a book in three weeks, or creating a global women’s network from scratch), it’s easy to get daunted. But I have to remind myself that it’s fine.

There’s a first time for everything, and there’s only one way to find out if I can do this. And that is to do it, and keep on doing it until it is done.

March 26, 2020

The Gifts of Solitude Chapter 1: Feel What You’re Feeling

Hearing that many people were struggling with feelings of fear, isolation, and loneliness, I have been inspired by the corona-crisis to write a book about The Gifts of Solitude. I realised I have something useful to offer, having spent up to five months completely alone at sea, without seeing another human being, or even dry land, when I was rowing solo across oceans. The solitude, and the fear, were very real. I had to find coping strategies, and eventually came to appreciate solitude as a pathway to emotional maturity and self-reliance.

So I have set myself the challenging but, I think, do-able task of writing a short book on the subject, aiming to publish around mid-April. But knowing that time is of the essence, and it’s important to get the content out there as soon as possible to support people in these trying times, I am going to publish previews of draft chapters as I write them – both here on my website, and on Medium.com.

My wonderful Italian friend Milena Fraccari (who has been in lockdown longer than most of us) has created a beautiful new website for the project – please share the link with friends who you think could benefit. They can sign up for updates, and find these draft chapters, plus the podcasts, videos, etc. I have reunited with Producer Vic Phillipson to do a video/podcast on an ad hoc basis – probably every couple of days.

My greatest wish is that this content will be useful to you. If you are feeling scared or lonely in your solitude, I hope it will bring you peace. If you’re surviving solitude, but enduring rather than enjoying it, I hope it will help you appreciate its opportunities. And if you’re relishing this chance to escape the daily routine, I hope this book articulates what you already know to be true to the extent you will want to share it with friends and family who have yet to find the gift in these times.

Call to Action: Obviously, I am offering this content – for free – because I want to do what I can to support my fellow humans in these difficult times. But like many, many others, I am suffering financially because of the coronavirus – my main source of income is keynote speaking at conferences, all of which have been cancelled for the foreseeable future. I have the chance to earn a few cents, ooh, maybe even dollars, according to how many people read my articles on Medium, and for how long. So you would be doing me a huge favour if you would please read the rest of this on my Medium page.

Chapter 1: Feel What You’re Feeling

“But feelings can’t be ignored, no matter how unjust or ungrateful they seem.” – Anne Frank

There is a good reason why solitary confinement has long been regarded as one of the harshest possible punishments: it’s hard. Humans are fundamentally social creatures.

For many millennia our survival depended on being part of a tribe. Alone, we were vulnerable. Together, we could share the workload, pool resources, and care for each other when we were young, old, or sick. Humans who were sociable would have a better chance of surviving, and passing on their genes.

Apart from practical considerations, there are also the emotional needs. We know that children who are deprived of social contact, such as those in Romanian orphanages, suffer severe developmental problems. Most humans need a sense of connection, to see and be seen, to hear and be heard. Of course, being in company is no guarantee of these things, but having no company at all can be deeply unsettling.

At the same time, for most people it’s normal to want some time alone, to think, process emotions, or take a break from talking. But normally we get to choose when and how we spend our alone-time, and for how long. Prolonged isolation can lead to physiological changes in the brain that makes rats fearful and aggressive, and scientists believe the same is true of humans.

Add fear into the mix, such as worries about infection, or financial concerns, and not only can the solitude become even more oppressive, but your immune system can be affected – exactly what you don’t want when there is a pandemic raging. Feelings of loneliness can actually affect your health, even your lifespan.

And solitude gets a really bad rap in popular culture – love songs where loneliness equates to heartbreak, commercials in which success and happiness equate to drinks/holidays/product-of-choice enjoyed in the company of friends throwing back their heads in laughter, Friends and its ilk – where solitude equals bad and gregarious equals good.

We are bombarded by messages that only losers are alone, while winners are surrounded by wonderful, charming, hilarious company. But is that really true?

——————————-

You might take the view – and I would have to agree with you – that because I had chosen to put myself in a solitary situation, alone on a rowboat on my way across an ocean, that I had surrendered all right to complain about the predicament in which I then found myself.

In my defence, it didn’t feel to me like my choice had been entirely voluntary. Maybe in the same way that someone feels an overwhelming urge to have children, like there’s some force beyond our control that is calling us to do something, I had felt deeply called to embark on this adventure. It would be easy for me to say that it was because I’d had an environmental awakening, and desperately wanted to do something to raise awareness of our looming global crisis, and rowing solo across oceans was my way to get people’s attention. That would be true, but it wouldn’t be the whole truth.

There was something deeper calling me out onto the ocean, a desire to find out who I was, and what I was capable of, some kind of impulse to test myself against a huge and daunting challenge. I was a willing accomplice to whatever force was driving me to do this crazy thing, but it also didn’t feel like it was entirely an act of free will. When I had received the call to adventure, I felt blindsided but also excited, and soon realised that to refuse the call would feel like a betrayal of some kind of soul-self that was urging me to transcend my limits.

The trouble with believing that some kind of higher power has called you to do something, is that when that something turns out to be a great deal harder than you ever imagined, it’s easy to feel mightily pissed off about it. I felt like a parent or a trusted teacher had invited me to do a task so far beyond my abilities that it looked like they were setting me up to fail.

Still, I told myself, I had vowed not to be one of those adventurers who decide to do something, and then complain vociferously about how unpleasant it is. I didn’t want my blog posts from the ocean to be an endless litany of grumbles. So I put on my best stiff upper lip, pasted on a metaphorical smile, and tried to pretend I was enjoying it.

Needless to say, this made it much, much worse.

——————————-

If Pollyanna’s Glad Game works for you, I’m very happy for you. But it didn’t work for me.

I understand why friends, family, even authors, urge us to focus on the positive, and be grateful for what we have. It’s not for our sake. It’s because they don’t like to listen to our whingeing.

When I tried to glad-game my situation, it simply added another layer of stress to what was already a very stressful situation. It made me feel guilty and inadequate for not coping better. I was assailed by the must and should and ought of trying to be cheerful.

On Day 58 of the Atlantic crossing, I posted this note to my blog, titled “Cheerfully Miserable”:

Last night I finally admitted to myself that I am not enjoying this. I’d been so determined that I would enjoy it, it has taken me until now to admit that I was wrong. (There then follows usual litany of whinges – oars broken, food cold, bed wet, shoulders aching, stereo kaput, flapjacks finished etc etc etc.)

But it’s OK.

In fact, when I made this honest admission to myself, I felt as if a weight had been lifted from my weary shoulders, the burden of pretending to myself or anybody else that this is fun.

Because it doesn’t matter. I am still achieving my personal objectives out here, and whether I am enjoying it or not is irrelevant.

In fact, it is even a good thing that I am not enjoying it. My mountaineering friend Sebastian, who was killed by an avalanche in Peru in 2003, once said, ‘The greater the suffering, the sweeter the summit’. If I was finding this easy and fun, the ultimate sense of achievement would be less.

This row has already pushed me beyond what I thought I was capable of enduring. For the most part I have found it unpleasant, uncomfortable and exhausting. It has taken every ounce of my resolve and determination to keep going. When I arrive in Antigua (God willing) the knowledge that I struggled and still succeeded will sweeten the final accomplishment a hundredfold.

I figured this out at the start of my night shift last night, and spent the rest of the three hours cheerfully hating every moment.

——————————-

And this is the point: we have to feel what we’re feeling. If we try to suppress emotions that our family or our culture have told us are bad or unworthy, they just get louder. It’s like trying to hold an inflatable beach ball under the water. It just wants to pop back up again. The harder we push it down, the more energetically it’s going to burst through. You’ve probably heard the saying, what you resist, persists. In my experience, it’s true.

At times, emotions like fear, anxiety, loneliness, or depression are a perfectly rational response to the situation in which you find yourself. (And also times when they are not, in which case you should seek professional advice.) Rather than suppressing or numbing what we’re feeling, there is real value in honouring our emotions. Rather than running away from them, we can turn around and dive deep into them.

——————————-

You might have heard the story about the cows and the buffalo. I haven’t witnessed this personally, so can’t vouch for its veracity, but let’s not let the facts get in the way of a good metaphor.

When they see a storm coming, cows will apparently run away from the storm (to the extent that cows ever run). This is what a lot of us do. Storms are scary, so we try to run away from them.

The problem is that eventually that storm catches up with the cows, and because the storm and the cows are moving in the same direction, the cows spend a lot longer than they needed to being bombarded with wind, hailstones, thunder and lightning.

The buffalo do the opposite. They head straight into the storm. This sounds counter-intuitive, but think about it. The buffalo and the storm are moving in opposite directions, so although they still feel the full fury of the storm, pretty soon they’re out the other side and back into the sunshine. The cows prolong the agony, the buffalo get it over and done with.

We can fight reality, we can try all kinds of diversionary tactics to avoid reality, we can try to ignore reality. Our strategies might even work for a while, and we think we’ve beaten reality.

But reality will have its wicked way with us, sooner or later. In my experience, sooner is better. The sooner we get present to the reality of our situation, and our feelings about our situation, the sooner we get to that sunshine on the other side, where we can look back at the storm and appreciate the gifts it brought us.

——————————-

To ponder:

What is going on for you right now, in this moment? What is your reality? What are your feelings about your reality? Feel what you’re feeling, without judgement. Allow your feelings to be what they are, without labelling them good or bad. Simply be a witness to your inner state.

What feelings are you avoiding? What are you numbing, or suppressing? What would it be like if you invited that feeling to come and sit with you, talk with you, explain to you why it is present? What would it be like if you welcomed that feeling as a reminder that you are human, and humans have feelings? What would it be like if you understood the presence of that feeling as a reasonable response to the circumstances in which you find yourself?

I hope you enjoyed this post. Please share!

March 19, 2020

Dos and Don’ts of Coronavirus

Bearing in mind that I am emphatically not any kind of medical expert, nor epidemiologist, nor doctor…. Here is what I’ve gleaned from reasonably authoritative sources around the internet. I’ve included some voices that go against the current prevailing view, i.e. they cast doubt on the threat actually posed by the virus – see the link to Dr Wolfgang Wodarg below. I have not included conspiracy theories, which can be fun to look at, but are almost always inherently unprovable. If you’re self-isolating or in lockdown, you’ve got time to check those out for yourself.

First (as the words on the cover of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy would say), don’t panic!

First (as the words on the cover of The Hitch Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy would say), don’t panic!

And also, please don’t panic-buy. It’s selfish. The supermarkets say they are keeping the usual supply chains open (so far at least) so why does my local supermarket look like Russia in the 1980s? How many bananas can you eat before they get overripe anyway? Don’t hog all the toilet paper for yourself – be public-spirited and just take what you need, else you’re creating artificial scarcity for everybody else. The tragedy of the toilet paper commons.

Do rely on authoritative, unbiased information, like the World Health Organisation. They have all the information you need, and none that you don’t. Trashy news outlets will give you trashy information.

Do wash your hands every time you come home from a public place, for at least 20 seconds, with hot water and soap. This is your #1 way to prevent infection to yourself and your family.

Do wear a mask if you are infected. Not a great deal of point if you’re not.

Do keep your distance, about 6 feet away from people. Don’t go out if you don’t have to. Avoid crowded places. This could be a good time to reconnect with nature – it’s relatively safe, and will help keep you sane and grounded in these challenging times. Get to enjoy your own company.

Do be sensitive to the fact that a lot of people will be suffering immense hardship. As well as those who are sick or dying or bereaved, a lot of people will lose income, jobs and/or homes. Don’t near-as-dammit say “let them eat cake” a la Melania Trump. Whether or not the coronavirus threat is real (see below), the fear is – yet again, proof that our thoughts create our reality.

Do pay appropriate attention to what is going on, but don’t let fear of coronavirus rule your life. Coronavirus is serious, but it isn’t everything. It’s a good time to remember the serenity prayer: have the courage to change the things you can, the serenity to accept the things you can’t, and the wisdom to know the difference. If you have more free time on your hands than usual, do use it productively – read books, play games with your family, journal, think about your future plans, paint, draw, write, learn a new language, tend your vegetable garden (hopefully said in a non-Melania kind of a way). Feel gratitude for the gifts of non-busy-ness.

Do volunteer with a local organisation doing work like arranging calls with elderly people who are confined to their homes for their own wellbeing, but are also more prone to loneliness. It will be good for their wellbeing – and yours.

Do organise video calls with friends, one-to-one or as a group. Self-isolation doesn’t have to mean loneliness – we can use the extra time that a lot of us have to reach out, connect, build community and psychological resilience. Or take this time to connect with people you haven’t seen for a while – “hey, just checking in, wanted to make sure you’re okay”. Coronavirus can be an excuse to resume contact, should an excuse be needed (which, incidentally, it actually isn’t).

If you’re a government:

– Don’t disband your pandemic department – and if you have disbanded it, reband it pretty damn quick. COVID-19 isn’t the first, and it won’t be the last pandemic. (This reminds me of the legendary Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s dissenting opinion on the abolition of part of the Voting Rights Act: “Throwing out preclearance when it has worked and is continuing to work to stop discriminatory changes is like throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet.” Just because you haven’t had a pandemic in a while doesn’t mean you don’t need to plan for one.)

– Do be transparent and science-based. Don’t just say you’re being transparent and science-based. That is not at all the same thing. (Take note, BoJo.)

I have PM envy. Love this guy.

I have PM envy. Love this guy.– Be clear, calm, and authoritative, and inspire confidence that you know what you’re doing. This is what your citizens pay you for. The Prime Minister of Singapore shows how to do it.

– Don’t pretend you know as much as the medics – they have devoted a lifetime to becoming experts at what they do, and it’s disrespectful to their devotion and expertise to claim you know more than they do.

– Do whatever you have to do to make sure people can get tested. You can’t be science-based if your country is not playing its part to get real data about infection rates.

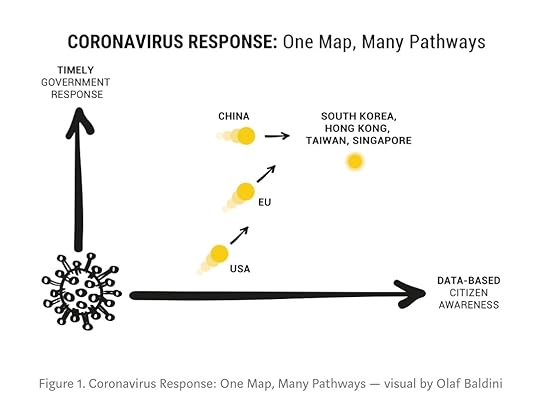

– Be bold in doing what is necessary. This is a crisis. People are looking to you to keep them safe, and that is your job. Let me say that again – KEEPING PEOPLE SAFE IS YOUR JOB. This is more important than the stock market, or your donors, or whoever else you’re trying to keep happy. Look at South Korea, China, Italy, Singapore, Hong Kong and Taiwan – that is what “doing what is necessary” looks like.

Do be informed. The best sources of information I’ve found so far:

Do be informed. The best sources of information I’ve found so far:

– TED’s Chris Anderson interviews infectious disease expert Adam Kucharski.

– I’m a big fan of Otto Scharmer and his work with the Presencing Institute and Theory U. Here is his take on coronavirus. I especially applaud this sentiment:

“What if we used this disruption as an opportunity to let go of everything that isn’t essential in our life, in our work, and in our institutional routines? How might we reimagine how we live and work together? How might we reimagine the basic structures of our civilization? Which effectively means: how can we reimagine our economic, our democratic, and our learning systems in ways that bridge the ecological, the social, and the spiritual divides of our time?”

– There is an interesting countervailing view from Dr Wolfgang Wodarg, presenting an apparently data-based view that the coronavirus is always present, and always fatal in a small percentage of cases. In other words, the current “pandemic” is nothing out of the ordinary. His view seems to be that the current situation is a media-fed mass hysteria whipped up by virologists wanting to be politically important and/or to raise funding for their labs. Ironically, the video linked above is also linked to a fundraiser – for a documentary about the coronavirus. I leave it to you to make up your own mind. (I also recommend this level-headed article from a writer in Florence, Italy.)

Do take this as an opportunity to build resilience. How can you and your family become more self-reliant, emotionally and logistically? How can you be better-prepared for future shocks to the system? (Hint: that doesn’t involve stockpiling a ten-year supply of toilet paper, but might involve learning how to make your own.) Take this as a wake-up call, and create systems and structures (and community gardens) to help future-proof your community, no matter what the future holds. I’m currently working on ideas around how the Sisters can be instrumental in increasing global resilience.

Do be curious and grateful about the gifts of these times. Carbon emissions declining. Polluted skies clearing. Life directions clarifying. All we know now is that things will change – and we might have an opportunity to change them for the better. Maybe these times of tumult are making way for something positive to emerge.

Book Recommendation:

If you have time on your hands for reading, I thoroughly recommend Upstream: The Quest to Solve Problems Before They Happen, by Dan Heath. It’s very readable, and will get you thinking proactively about root causes, and nipping problems in the bud before they become a crisis. We could do with an awful lot more upstream thinking in the world – everywhere, but especially in some sectors of our political leadership. I’ll share some highlights of the book in next week’s blog post.

Course Recommendation:

Seeing as my permaculture course has been cancelled due to coronavirus, I’m signing up for Otto Scharmer’s impromptu course, created in response to the virus. In case you missed the link in his Medium article, here it is: GAIA: Global Activation of Intention and Action.

And finally….

There have been some beautiful and uplifting odes to the gifts of coronavirus. Here are a few:

An Imagined Letter from Covid-19 to Humans

from Kristin Flyntz

A sample:

Last year, the firestorms that scorched the lungs of the earth

did not give you pause.

Nor the typhoons in Africa,China, Japan.

Nor the fevered climates in Japan and India.

You have not been listening.

It is hard to listen when you are so busy all the time, hustling to uphold the comforts and conveniences that scaffold your lives.

But the foundation is giving way,

buckling under the weight of your needs and desires.

We will help you.

We will bring the firestorms to your body

We will bring the fever to your body

We will bring the burning, searing, and flooding to your lungs

that you might hear:

We are not well.

Despite what you might think or feel, we are not the enemy.

We are Messenger. We are Ally. We are a balancing force.

An invitation to simply enjoy this space, by Emma Zeck

A sample:

With this open time

You do not have to write the next bestselling novel

You do not have to get in the best shape of your life

You do not have to start that podcast

What you can do instead is observe this pause as an opportunity

The same systems we see crumbling in society

Are being called to crumble in each of us individually

Enjoy! And be safe, be well, be kind.

March 12, 2020

Christiana Figueres vs Tony Robbins

Christiana Figueres is one of my heroes. As executive secretary of the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, she was the architect of the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015. When she talks about how they pulled off an unprecedented international agreement on climate change, the scale of her accomplishment becomes even more impressive. I will say more about that in a moment…. Along with the reason why I’m pitting her against self-help maestro Tony Robbins.

But first, a quick plug: I’ve got a new Medium article online – if you sometimes get the jitters around public speaking, difficult conversation, or anything else, I hope you find this useful advice on how to connect with your inner calm. Please enjoy, clap, and share!

And second… coronavirus. Wow. What a difference a week makes. Besides my work as a keynote speaker being impacted by conference cancellations and postponements, our Sisters retreat in Tuscany in June is now under serious threat. But these are as nothing compared with some of the deeper impacts of the virus, and even more so, the fear of the virus, which is getting stoked on a daily basis by the media. I am sure that a great many small businesses, especially in countries that depend heavily on tourism, will go to the wall before this is over. It is going to cause a great deal of suffering.

In whatever way, and to whatever extent, you are being impacted, you have my sympathy. Let’s keep calm, wash our hands, and carry on. (And let’s also keep it in proportion – after all, in the long run climate change is a much greater existential threat.)

Okay, on with the blog…

Christiana Figueres

Christiana FigueresThe other day I was listening to Christiana Figueres being interviewed onstage at the Royal Society of Arts in London (I thoroughly recommend the video in its entirety – informative, entertaining, and inspiring) in which she described how, in the run-up to the Paris COP, she and her team realised:

“We can’t settle for what is good, we have to push for what is necessary.”

All in secret, they set about building an enormous network of companies, religious leaders, and other influencers – in every country around the globe – and built a system that would enable them to respond to what was happening in the negotiating room in real time.

Christiana’s co-conspirator, Tom Rivett-Carnac, a former Buddhist monk, was inside the negotiating room, and would get the nod from Christiana if one of the negotiators wasn’t playing ball. He would then call his secret team, who were located in a completely separate building, and the hidden network would swing into action. Someone on the team would call a person who would call a minister who would call the person in the negotiating room… and with the support of this network of allies, Christiana would get the result that she wanted.

But what I loved most about this conversation was the response that Christiana gives to a question towards the end of the video, which is very much in keeping with her Buddhist philosophy, and is at the same time both deeply personal and totally universal:

“At one point there was a huge knot in the negotiations because industrialised countries were refusing to accept their historic responsibility, and were blaming developing countries that all future emissions were going to come from them. And conversely developing countries were blaming industrialised countries that they had caused climate change – which is factually true; it’s not ideology. And they weren’t even able to talk to each other about this. There was a constant blaming going on, and a constant “who is the victim of who?”.

And my Buddhist studying at that time had made me realise that if you get into the victim/perpetrator role, that all of us have in so many aspects of our life, that that victim/perpetrator role is one that is completely impossible to win. Because the moment I accuse you of being my perpetrator, you will not stand still. You will then turn around and tell me that I am actually your perpetrator….

And I also realised that I was doing that in my own personal life. And I had viewed myself as a victim, and had pointed accusatory finger at my former husband, who I had identified as being the perpetrator. And it was very clear to me that as long as I embodied that reality, what I was responsible for was not going to untangle itself. And because what is true at one level of the system is true at all levels of the system, my first responsibility was to take myself out of that victim/perpetrator role. Because if I continued to do it, I would see all the countries continue to do that, and we would never have gotten to the Paris Agreement.

So it wasn’t until I did my own little homework, and it wasn’t easy, and I’m still working on it (laughter from the audience), and took the edge out of that and began to see that this really is a completely fruitless and endless discussion that helps no one. The only way out was to exit that and to see everything from the observer role, which is what you’re taught in these Buddhist practices. And lo and behold, and although it took a heck of a lot of work, and quite a long time, it was when I shifted that that I began to see the shift in the international negotiations. I’m not claiming a direct causal link, but I’m also not claiming that it was coincidence.”

(Cue massive applause from the audience.)

And it also struck me that her approach is very yin, focusing on the outer result as a reflection of the inner state. To change the result she is getting, she changes herself.

Tony Robbins

Tony RobbinsThis contrasts with, say, Tony Robbins. When I thought about this, it was almost comical. I don’t know Christiana’s height, but looking at her standing behind a podium, or with other people, I am sure she is a LOT closer to five foot than to six. Compare her with Tony Robbins, who is a giant of a man – due to a condition called acromegaly arising from a tumour on his pituitary gland, he put on a huge growth spurt in high school, ending up at around 6 foot 7 inches, with the characteristic large hands and feet, and Desperate Dan jawline. (Richard Kiel, the actor who played Jaws in two James Bond movies, also had it.)

But the contrast I’m thinking about isn’t really the physical one. I’ve got great respect for Tony – he is amazing at what he does, a total NLP ninja – and it hit me that, compared with Christiana’s yin-ness, Tony is very yang. He’s big, he’s loud, he’s somewhat domineering. His events are characterised by thousands of people getting enormously over-excited, desperate for the opportunity to be “cured” by the man, as if he is a modern day Messiah.

Although his technique hinges on altering their inner state, often by delivering a visceral shock to their system to jolt them out of their habituated pattern of thinking, it still feels to me like it is something he does to them. He is subject and they are object. They are broken, and he fixes them.

This video of Tony curing a stutterer would be a perfect example, with the tagline: “30 years of stuttering, cured in 7 minutes!” It really does look like a modern-day miracle. (“Lazarus dead for 4 days, resurrected in 5 seconds!”) And I defy you not to get a lump in your throat at the end. I totally did.

Of course, both Christiana and Tony are both yin and yang. Christiana had to bring a whole load of yang to the party to assemble that global network of leverage points, and Tony’s greatest masterpiece is possibly himself, having done deep work on his inner state to achieve spectacular external results. So I’m definitely cherry-picking these two narrow instances to illustrate my point – but I hope the point is made.

So where am I going with this? I believe it has deep implications for the way we try to address the challenges facing the world right now.

In the past, we’ve been holding out for a hero (to channel Bonnie Tyler). We’ve wanted a big, bold, brave, Tony-type person to come along and fix it. If we could just find the right hero with the right superpowers, everybody will be saved.

But now, my belief is that we need a different kind of hero – and if you’ll go and take a look in the mirror, you’re looking at one. We can’t sit around waiting for somebody else to come and be the subject to our object. Our problems now are too big and too interconnected for any one person to save us.

So I, for one, am going to be taking inspiration from Christiana Figueres, knowing that I have to do my own inner work before I can start to create any worthwhile transformation externally. Our present reality is the outer projection of whatever is going on inside (getting close to) 8 billion heads and hearts. When we heal ourselves, we start to heal the world.

As the saying goes: you give a person a fish, you feed them for a day. You teach them how to fish, you feed them for a lifetime. Likewise, you give a person a miracle, you help one person. You teach them how to work miracles (or remind them that they already can), you help the world.

Other Stuff:

Following on from last week’s earthling/extra-terrestrial theme, you might enjoy this episode of the After On podcast in which Rob Reid talks to astronomer Avi Loeb about a very unusually-shaped object currently passing through our solar system, and the possibility that it might not be a naturally-formed object (i.e. it might be a product of an alien intelligence). More about that Oumuamua asteroid in article form here.

Oh, and the ET theme also led me to listen to this podcast: This Movie Changed Me, from the On Being network. This particular episode was about the movie Contact, which I hadn’t seen since soon after it came out in 1997…. So of course then I had to watch the movie again. It has stood the test of time well. Primed by the podcast, I especially appreciated the dynamic between Jodie Foster, representing rational science, and Matthew McConaughey, who plays a priest and represents the faith-based perspective. Recommended!

If you want to learn more about Christiana Figueres, I also recommend her TED Interview with Chris Anderson. You will learn a lot more about her background (specifically how her father went from being a rebel in exile to president of Costa Rica, where he abolished the army and committed the country to environmental stewardship), and about her unique brand of “stubborn optimism“.

March 5, 2020

Calling All Earthlings

During my morning walk yesterday I was listening to Krista Tippett on the On Being podcast interviewing Jill Tarter, astronomer and co-founder of the SETI Institute, the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence. (You can find the podcast at It Takes a Cosmos to Make a Human.) Jill was the inspiration behind the Jodie Foster character in the movie Contact, based on a novel by the cosmologist and visionary Carl Sagan.

A couple of weeks ago I mentioned the overview effect, the phenomenon experienced by astronauts looking back at our Earth from afar, and appreciating its vulnerability, uniqueness, and preciousness. The SETI perspective is somewhat similar. I’ll come back to that in a moment, but first, some background.

The SETI Institute was founded in 1984, and has been searching for evidence of extra-terrestrial intelligence ever since. Despite massive progress in Earth-based and space-based telescopes, no luck so far.

Admittedly, we’ve only explored up to around 4 billion miles from Earth, which would be a good long walk, but in the overall scale of the universe – or even the Milky Way – is effectively just around the corner, not even outside our own solar system.

But if there was intelligent life out there, rather than us having to go looking for it, wouldn’t it have made contact with us?

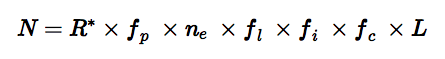

This is where we come to the Drake Equation. (Ah, thank heavens! you may be thinking… for once she’s not banging on about the IPAT equation!)

Simple, right?!

Actually, it’s quite easy to make sense of it once you know what the variables mean.

(Not to be confused with the search for Intelligent Wife.)

(Joe Scott does a good explanation of it on this video.)

According to Wikipedia, current estimates of the value of N (N being the number of civilisations in the Milky Way) vary from 9.1 × 10−13. i.e., suggesting that we are probably alone in this galaxy, and possibly in the observable universe, to 15,600,000, i.e. our galaxy is pretty darn crowded with friends (hopefully) we just haven’t met yet.

This brings us to the Fermi Paradox, most concisely stated as, “But where is everybody?” If there is indeed intelligent life out there, where are they? Haven’t they seen the Hollywood sci-fi movies? – they’re supposed to say hi to the humans, and ask to be taken to our leader!

(Joe Scott is good on the Fermi Paradox too.)

Suggestions fall into four main categories:

– we actually are all alone

– intelligent extra-terrestrial beings are extremely rare

– they exist – or who knows, could even be here already – but for various reasons we see no evidence (e.g. they exist in a dimension not perceivable by us, they choose to remain hidden, they are waiting and watching, etc.)

– the lifetime of such civilisations is short

This last category is maybe the most cautionary one. As I’ve written before, human empires are historically short-lived. It’s only been 50 years since the moon landing, and already we’re staring down the barrel of our own collapse. Hopefully we will have many centuries of space exploration ahead of us, but that is far from certain. For interplanetary civilisations to make contact with each other, they need to have some chronological overlap (adjusting for the speed of light) in which one civilisation has the technology to transmit, and another has the technology to receive the transmission.

As of now, we have yet to find any evidence of life on planets other than our own, let alone intelligent life. As far as we know, we might be all there is.

How does that make you feel? Special? Lonely? Grateful to be alive?

We take ourselves so much for granted, and yet we are absolutely amazing (even on a bad hair day). We have these incredibly useful and adaptable bodies that can climb mountains and row oceans. We have brains that have found ways to split the atom and understand quantum physics. We have emotions that make us capable of superhuman courage and allow us to appreciate the beauty of a symphony or an oil painting. Yet we walk around like we’re just another run-of-the-mill creature, rarely pausing even to appreciate our opposable thumbs (which we mostly use for texting on smartphones).

Jill Tarter’s main point, much like the overview effect mentioned above, is – we’re all on this Earth together. From down here, we mostly see what makes us different. But from space, we would all look very similar. An alien might notice that humans come in different shapes, sizes, and colours, but to the alien we would all be Earthlings, united by our shared habitation of this beautiful and infinitely varied planet. The alien might think it strange that we squabble with each other, make a mess of our home, and generally behave in ways incompatible with our long-term health and wellbeing.

As Jill says, if we would only recognise our shared humanity, and our shared dependence on this very special lump of rock, it goes without saying that we would take better care of it – and of each other.

I’ll leave you with Monty Python’s Galaxy Song…. Especially fast forward to the last two lines (lyrics below the video). And also Carl Sagan’s beautiful words about the pale blue dot.

Whenever life gets you down Mrs. Brown

And things seem hard or tough

And people are stupid, obnoxious or daft

And you feel that you’ve had quite enough…

Just, remember that you’re standing on a planet that’s evolving

And revolving at nine hundred miles an hour

That’s orbiting at nineteen miles a second, so it’s reckoned

A sun that is the source of all our power

The sun, and you and me, and all the stars that we can see

Are moving at a million miles a day

In an outer spiral arm at forty thousand miles an hour

Of the galaxy we call the Milky Way

Our galaxy itself, contains a hundred billion stars

It’s a hundred thousand light years side-to-side

It bulges in the middle, sixteen thousand light years thick

But out by us it’s just three thousand light years wide

We’re thirty thousand light years from galactic central point

We go round every two hundred million years

And our galaxy is only one of millions of billions

In this amazing and expanding universe

The universe itself keeps on expanding and expanding

In all of the directions it can whiz

As fast as it can go, the speed of light you know

Twelve million miles a minute and that’s the fastest speed there is

So remember when you’re feeling very small and insecure

How amazingly unlikely is your birth

And pray that there’s intelligent life somewhere up in space

Cause there’s bugger-all down here on Earth

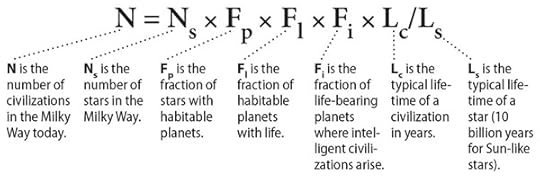

Carl Sagan on the Pale Blue Dot:

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there-on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.

The Earth is a very small stage in a vast cosmic arena. Think of the endless cruelties visited by the inhabitants of one corner of this pixel on the scarcely distinguishable inhabitants of some other corner, how frequent their misunderstandings, how eager they are to kill one another, how fervent their hatreds. Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot.

Our posturings, our imagined self-importance, the delusion that we have some privileged position in the Universe, are challenged by this point of pale light. Our planet is a lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark. In our obscurity, in all this vastness, there is no hint that help will come from elsewhere to save us from ourselves.

The Earth is the only world known so far to harbor life. There is nowhere else, at least in the near future, to which our species could migrate. Visit, yes. Settle, not yet. Like it or not, for the moment the Earth is where we make our stand.

It has been said that astronomy is a humbling and character-building experience. There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

― Carl Sagan, Pale Blue Dot: A Vision of the Human Future in Space

February 27, 2020

Kahneman, the Commons, and the Power of Accumulation

After my more environmentally-focused talks, I often get a question along the lines of “I’m just one person out of billions on the planet – how can anything I do make any difference?” I always try to emphasise that it all makes a difference.

Part of the problem here is our preference for instant gratification: for many people, we want to see results, and we want to see them quickly. The human brain is not well wired to appreciate the subtle accumulation of tiny actions over time and across large populations. Per Daniel Kahneman’s WYSIATI (we think that What You See Is All There Is), we do not have a strong relationship with lines of causality stretching into the past or into the future, nor for events taking place in far-distant parts of the world.

Daniel Kahneman

Daniel KahnemanMy rowing voyages brought home to me, in a deep and visceral way, how oarstrokes, 3-hour rowing shifts, and days and months of rowing add up to a significant result – and likewise how skipping rowing shifts or cutting them short can also accumulate. For better or worse, it’s the little habits that add up to big differences.

But you don’t have to be an ocean rower to see this. We all see it, whether it is the accumulation of surplus calories around our middle, or an addiction that leads to a predictable (and yet somehow always unexpected) disease, or even a distressingly large credit card balance made up of many, seemingly insignificant amounts. It seems that as humans we’re destined to be constantly surprised by the impacts of accumulation.

Most of our environmental issues have resulted from an array of tragedies of the commons, where individuals act out of self-interest, taking just a little bit of a shared resource – a few fish from the sea, or a few trees from the edge of the forest – or polluting just a little bit – one plastic water bottle a day, or a few extra leisure flights each year – and these individual self-interested actions accumulate to create a major impact, until the resource is exhausted or extinct. (More examples here.)

At TED Mission Blue, I pointed out the negative aspect of accumulation:

“Generally, we haven’t got ourselves into this mess through big disasters. Yes, there have been the Exxon Valdezes and the Chernobyls, but mostly it’s been an accumulation of bad decisions by billions of individuals, day after day and year after year. And, by the same token, we can turn that tide. We can start making better, wiser, more sustainable decisions. And when we do that, we’re not just one person. Anything that we do spreads ripples.”

And related it back to the metaphor of a rowing voyage:

“Every action counts. Each of my ocean crossings takes about a million oarstrokes. I could have stood under the Golden Gate Bridge and said “one stroke isn’t going to get me anywhere”. But you take a million, or 7 billion, tiny actions, and you string them all together, and you really can achieve almost anything.”

This power of accumulation emphasises the importance of good habits. Humans are creatures of habit; hard thinking (Kahneman’s System 2) costs the brain a lot of calories, so it automates as much as it can into default routines, which are hard to disrupt.

In my experience, the best way to create better habits is to make them a matter of identity. I learned this on the boat. I don’t especially like physical exercise, so it was always a battle of willpower to get myself to row for 12 hours a day. But then I realised that I wanted to be able to look back at my time on the ocean and feel proud of how I had conducted myself. I wanted to identify as a person who could show up in a professional way, demonstrating commitment and discipline.

Kahneman highlights the difference between feeling “happy in one’s life” and “happy about one’s life” (see his TED Talk). We each have a preference somewhere on the continuum between these two extremes. The pure hedonist wants happiness in the moment, while the ascetic wants to feel they’ve led a good life. I found that I skewed sufficiently towards the latter that I could overcome my dislike of exercise, knowing that I was serving my longer-term purpose of being able to look back without shame or regret.

So if I wanted to identify as a professional adventurer, I had to show up and be professional. If I want to identify as an environmentally conscious person, I have to remember my reusable grocery bag, bottle, and cup when in public; I choose an economical car; I don’t fly unnecessarily.

As well as helping us develop positive habits, this habit/identity philosophy enables us to spread ripples of change without preaching. By consistently being the change we want to see in the world, we take the yin approach, rather than the yang way which involves talking about it, or trying to force other people to change through legislation or brute force. We can see in the United States how a significant proportion of conservatives respond to the perceived finger-wagging of the liberals; they become ever more entrenched in their views, and take a perverse pleasure in behaving and voting against the liberal agenda, even when it involves cutting off their nose to spite their face.

Trying to persuade other people to change very rarely works. Being the change just might.

So what kind of change are you being?

February 20, 2020

All The Time In The World

Last week’s blog post (rather wordily titled The Ecological Elephant In The Room Goes Up The Creek Without A Paddle) elicited some interesting responses. Thanks especially to Inka for pointing me in the direction of some interesting pieces on population.

This article – Stop blaming population growth for climate change. The real culprit is wealth inequality – was interesting, but I was unconvinced. It is a critique of Dr Jane Goodall‘s remark at Davos that most environmental problems wouldn’t exist if human population was at the levels of 500 years ago. As you can tell from the title of the article, the author says it’s not about population, it’s about inequality. (And apparently Dr Jane was misquoted anyway.)

This article – Stop blaming population growth for climate change. The real culprit is wealth inequality – was interesting, but I was unconvinced. It is a critique of Dr Jane Goodall‘s remark at Davos that most environmental problems wouldn’t exist if human population was at the levels of 500 years ago. As you can tell from the title of the article, the author says it’s not about population, it’s about inequality. (And apparently Dr Jane was misquoted anyway.)

While I can readily believe that consumption by the world’s richest 10% makes up half of the planet’s consumption-based CO₂ emissions, I don’t see how that makes inequality the culprit.

Don’t get me wrong – I am one hundred percent in favour of greater economic equality. And I agree with the article that a key driver of our ecological woes is:

“the waste and inequality generated by modern capitalism and its focus on endless growth and profit accumulation”.

I also agree that:

“Developing regions in Africa, Asia and Latin America often bear the brunt of climate and ecological catastrophes, despite having contributed the least to them”

…and that this is grossly unfair.

But to me there is a huge and unfounded leap of logic to the statement:

“Inequalities in power, wealth and access to resources – not mere numbers – are key drivers of environmental degradation.”

You could argue that while the world is run by those with enormous power and wealth, who have the resources to insulate themselves from the worst impacts, or to even leave the planet entirely, they will have no qualms about screwing over the rest of us to maximise their profits. But the article doesn’t say that.

Yes, the wealthiest group degrades disproportionately, but if there was greater equality, I’m guessing there would be even more degradation. If more people had the money to fly more, have more homes and cars, and generally consume more, they probably would. Even if a gazillionaire has ten or even twenty homes, that is fewer homes overall than several billion people having two homes rather than one. Even if the gazillionaire flies every single day of the year, that is still fewer flights overall than several billion people taking ten flights a year.

So while I find it obscene that 26 billionaires have as much wealth as the poorest half of the world, and I wholeheartedly support the eradication of poverty, and I agree that ecological and social justice are inextricably connected, I don’t agree that it is the differential between the billionaires and the rest that is responsible for our problems. I think they simply have too much, and could be using it for more worthwhile causes than their own extravagant, carbon-intensive lifestyles.

Yes, I’m sorry – I’m going to have to mention the IPAT equation yet again.

Impact (environmental) = Population x Affluence x Technology

I’m sure that the distribution of the affluence has some influence on overall impact, but the much greater issue is the sum total of population, and the sum total of affluence (by which I really mean “material consumption”, because affluence doesn’t necessarily have to translate into degradation – it all depends on what the money is used for).

If you know me at all by now, you will know that I’m not one to defend the uber-wealthy. But I just don’t think the author has made a compelling case, if there is indeed one to be made. There may be correlation between rising inequality and environmental degradation, but I’m not seeing the causation – whereas with population growth and environmental degradation, I do. We need to address inequality as well as ecological destruction, but it would be misleading to assume that fixing the former will fix the latter.

So I’m with Jane Goodall on this one. If there were a lot fewer of us, we would have a much better chance of living comfortably while still leaving plenty of space and resources for the other creatures unfortunate enough to share this planet with us.

Inka also pointed me in the direction of a book called Empty Planet: The Shock of Global Population Decline, by Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson, and I’m going to do that unforgivable thing of critiquing a book without having read it. Mea culpa. But please bear with me – the book itself is not the point here.

From reading the blurb, it sounds like a reasonably balanced perspective, outlining the pros and cons of a peaking and then declining human population. The authors apparently:

“find that a smaller global population will bring with it a number of benefits: fewer workers will command higher wages; good jobs will prompt innovation; the environment will improve; the risk of famine will wane; and falling birthrates in the developing world will bring greater affluence and autonomy for women. But enormous disruption lies ahead, too. We can already see the effects in Europe and parts of Asia, as aging populations and worker shortages weaken the economy and impose crippling demands on healthcare and vital social services. There may be earth-shaking implications on a geopolitical scale as well.”

So far, so good. What really made my jaw drop, though, was a Goodreads rating by a certain Charles J who, while making the valid if somewhat pedantic observation that the authors should have written “cleft palate” rather than “cleft palette”, is also so emphatically pro-human that I would quite like to put him and Jane Goodall in a verbal cage fight together and see who wins. My money is on Dr Jane.

Charles’s concern is that, with the human population predicted to peak at around 11 billion in 2100, there won’t be enough dynamic young workers to keep the old folks in the style to which they would like to be accustomed.

Let me run some of these comments past you:

“In excess of ninety percent of such accomplishments [in science, art, exploration, or anything else] have been made by people under thirty-five. (Actually, by men under thirty-five, for reasons which are probably mostly biological, but that is another discussion.) The simple reality is that it is the young who accomplish and the old who do not.”

Ah! So a world like Logan’s Run, where humans are euthanised when they reach 30! Because who needs all that wisdom and experience that us old farts bring to the party? And while we’re at it, why not discard a load of those under-achieving females? Oh, but no, because we need them to have lots of babies. (Hello, The Handmaid’s Tale.)

Ah! So a world like Logan’s Run, where humans are euthanised when they reach 30! Because who needs all that wisdom and experience that us old farts bring to the party? And while we’re at it, why not discard a load of those under-achieving females? Oh, but no, because we need them to have lots of babies. (Hello, The Handmaid’s Tale.)

He criticises the authors for not personally producing enough children, and parenthetically mentions: “(Since you ask, I have five children. I am part of the solution, not part of the problem.)” And having critiqued the selfishness of western society, he rather contradicts himself by saying: “I cannot say why (the authors do not have more children], of course, and it would be unfair to assume a selfish choice. But whatever the reason, it is undeniably true that as a result they have less investment in the future than people with children.”

As a childless/child-free person myself, dear Charles, I can assure you that many of us care passionately about the future, not out of a vested interest in our own progeny, but because the future matters to us as thoughtful and responsible human beings. In fact, a growing number of young people are choosing not to have children precisely because of their concerns about the future, wanting to reduce their impact and/or reluctant to bring new lives into such an uncertain world.

And the bigger point is: if our current economic model is creating a demographic time bomb, then rather than continuing to expand the population to keep the model happy, change the model. Find another way to fund the elderly, or to help them stay healthier for longer, or create a new range of occupations to enable them (us?!) to continue being productive and contributing members of society, or…. there are lots of options. We created the model, and if it is no longer working due to changing demographics, change it.

So, I’m not going to fall into the Charles J trap and try to tell people how many children they should or shouldn’t have. Or even how much they should or shouldn’t spend. I am sure it will all sort itself out in the end – maybe not in time to save the humans, but whatever.

After all, the Earth has all the time…. in the world.

Finally, and somewhat relevantly, it has taken me a while to get around to Russell Brand’s podcast. A couple of friends had recommended it, but I had certain preconceptions and prejudices about him that put me off the man, based on things he has done in the past. But this morning I listened to his interview with astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who admittedly would be awesome no matter who he was in conversation with. Amongst many things, they talked about the “cosmic perspective”, also known as the “overview effect”, reported by astronauts who have seen the Earth from space. They actually paused the interview while NdGT looked up this quote on his phone, which I think is just fabulous:

Finally, and somewhat relevantly, it has taken me a while to get around to Russell Brand’s podcast. A couple of friends had recommended it, but I had certain preconceptions and prejudices about him that put me off the man, based on things he has done in the past. But this morning I listened to his interview with astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson, who admittedly would be awesome no matter who he was in conversation with. Amongst many things, they talked about the “cosmic perspective”, also known as the “overview effect”, reported by astronauts who have seen the Earth from space. They actually paused the interview while NdGT looked up this quote on his phone, which I think is just fabulous:

“You develop an instant global consciousness, a people orientation, an intense dissatisfaction with the state of the world, and a compulsion to do something about it. From out there on the moon, international politics look so petty. You want to grab a politician by the scruff of the neck and drag him a quarter of a million miles out and say, ‘Look at that, you son of a bitch.’”

— Edgar Mitchell, Apollo 14 astronaut

February 13, 2020

The Ecological Elephant In The Room Goes Up The Creek Without A Paddle

This blog post ends cheerfully, although has a lot of not-very-cheerful stuff on the way there. So if you’re feeling a bit anxious anyway, you might want to skip to the end, or at least pour yourself a stiff drink first (although definitely not before driving, and preferably not before breakfast).

First, though, a quick bit of news. I’ve got two new articles on Medium.com (well, actually, one of them came out a couple of weeks ago, but I forgot to tell you – sorry!). How To Overcome Your Own Self-Limiting Beliefs and, hot off the press yesterday, You Manifest What You Measure. Please read, enjoy, and share the love by sending to someone you care about who would benefit from these.

Right, now on with the blog…

Last October I wrote a blog post about the rise and fall of empires throughout history, inspired by the 1976 essay of Sir John Glubb, The Fate of Empires, which you can download for free here. I recommend it in its entirety (24 pages).

Some of it may rub up against contemporary social mores, particularly on immigration, but it is also insightful and prescient, foreshadowing the collapse of the Soviet Union, and even hinting at Brexit (he was writing in the early years of the formation of the EU) and the subsequent infighting between the Home Nations. If even 24 pages is too much, I’ve copied and pasted some quotes at the end of this blog post to give you a flavour, along with various other resources.

This week I’m picking up the somewhat apocalyptic theme of the decline of empires as I’ve just finished reading Immoderate Greatness: Why Civilizations Fail, by William Ophuls. As books go, it’s another short read – it took me about an hour and a half, and I’m not a particularly fast reader. And it’s also hard to go fast when it feels like you’re reading the death warrant of our world.

Ophuls provides a compelling synopsis, based on the historical record, of the six major factors that propel civilizations toward breakdown, saying that “civilization is effectively hardwired for self-destruction”. If you can find ways to refute his arguments, please tell me, because I’d like to believe it’s not true, and his case is quite convincing.

So here we go. Let’s dive into this cheery hypothesis and the six factors.

BIOPHYSICAL LIMITS

1. Ecological Exhaustion

As a civilisation expands, so does its ecological footprint. To date, every civilisation has centred around a great city (Rome, Athens, Istanbul, etc) and cities tend to: a) have a higher per capita footprint than the average for the rest of the nation, and b) conceal from their inhabitants the extent of the ecological impacts (soil degradation, deforestation, declining aquifers, etc.). Even before the resources are totally exhausted, the cost of exploiting them becomes unfeasible.

Part of the problem is the time lag before the problem becomes evident:

“Unfortunately, the benefits accrue immediately, but the debts come due only later, so the momentum of development continues.”

And another part of the problem is the “law of the minimum”, meaning that the variable that is in the shortest supply becomes the limiting factor. It doesn’t help a civilisation much if it has bountiful building materials, or even food, if it has a shortage of drinkable water.

In many ways, it’s not our fault. It’s in the nature of every species.

“In pursuing greatness, human beings are simply expressing their biological nature. Biological evolution is driven by the tendency of all organisms to expand their habitat and exploit the available resources—just as bacteria in a Petri dish grow until they have consumed all the nutrients and then die in a toxic soup of their own waste.”

Just like bacteria, humans will expand just as much as they can, given the prevailing conditions. But remember the law of the minimum? What if those conditions change – say, due to a change in the climate, human-induced or otherwise?

“The law of the minimum has a corollary: consuming to the limit when times are flush leaves a civilization exposed to peril if resources decline in quality or quantity… consistently pressing ecological limits is risky to the point of being suicidal.”

For more on that, see Kate Raworth and Doughnut Economics – we’re already over our limits on 4 out of 9 planetary boundaries. That leaves us really vulnerable and over-exposed to any change in conditions.

Oops.

2. Exponential Growth

As a species, we’re really rubbish at comprehending non-linear growth. Think of the bacteria in the Petri dish again, because we’re not so different. If they double in number every day, they’re probably still feeling pretty chill when their dish is one-eighth full. “Hey folks, loads of space – let’s stretch out and relax!” The next day their dish is still only one-quarter full. Still roomy. The next day it’s half full. Still no problem. The day after that….

Our population growth might be slower than bacteria, but it’s still happening really fast. The chart above might not look too scary. But how about this one, with a longer time span on the x axis?

Now we’re looking rather like those bacteria in the Petri dish.

Oops (#2).

3. Expedited Entropy