K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 2

June 23, 2025

Need a Good Book Editor? Top Up-to-Date Recommendations

Where do I find a good book editor?

Where do I find a good book editor?

This is without doubt the question I receive most frequently from fellow writers. It’s a hard question to answer because, while finding an editor is easy, finding a good book editor is something else again.

I originally published this resource many years ago after reaching out to trusted writing experts for their recommendations of freelance book editors. I also encouraged readers to share their own suggestions in the comments. Today’s is the latest in a series of updates I’ve made to keep the post current—and I plan to continue revisiting it regularly to ensure the information stays helpful and relevant.

The following editors are in alphabetical order, with their names linked to their websites, so you can do further research to discover which is best suited to your needs. I’ll continue adding to the list whenever an appropriate new name comes to my attention (you can always find the list on the Start Here! page—accessible from the site’s top toolbar).

If you’ve personally worked with a good book editor, please feel free to add his or her name and URL in the comments. (If you’re an editor yourself and would like to be included, please ask one of your satisfied clients to nominate you.) The goal is to make this as useful a resource for everyone as possible. New names will be included in the list when I update it again in the future, so in the meantime be sure to check the comment section for more resources!

The Top Recommended Freelance Book EditorsMarlene AdelsteinServices: Developmental Editing, Publishing Consultations, Screenplay Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Commercial Fiction, Thriller, Mystery, Women’s Fiction, Literary Fiction, Historical Fiction, Memoir, and Screenplay.

Affordable EditorsServices: Line editing, proofreading, developmental editing, comic book editing.

Rates: 1¢–1.5¢ per word

Specialities: Science fiction, fantasy, slice of life, historical fiction, memoir, non-fiction.

Services: Developmental edit, editorial assessment, line editing, copyediting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Fiction, memoir, flash fiction, academic articles.

Services: Editing, consulting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Sally ApokedakServices: Editing, consulting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Augustine EditorialServices: Developmental editing, copyediting, proofreading, sensitivity reading, beta reading.

Rates: 1.3¢–2¢ per word.

Specialities: Tales set in immersive worlds, stories inspired by S.E. Asian folklore, and slow-burn romantic subplots.

Black Wolf Editorial ServicesServices: Content editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Bookaholics Author ServicesServices: Line editing and copyediting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: PG-13 material.

Breakout EditingServices: Content editing, copyediting, proofreading.

Rates: 1¢–4¢ per word.

Specialities: Fiction, non-fiction, children’s books, memoir, short stories.

Vicki BrewsterServices: Developmental editing, copyediting, content editing, manuscript evaluation, academic editing, indexing.

Rates: $.50–$1.20 per 100 words.

Specialities: Long-form fiction.

Grace BridgesServices: Line Editing, Developmental Editing, Proofreading.

Rates: $3–$30 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy.

Averill BuchananServices: Development Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Indexing.

Rates: £10–£45 per 1,000 words or £1,00–£2,000 per 100,000-word book.

Specialties: Fiction, especially for independent/self-publishing writers.

Burgeon Design and EditorialServices: Coaching.

Rates: $1,200–$6,500.

Specialities: Diversity.

Kelly ByrdServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Crime and Mystery, Thriller, Romance, Literary Fiction, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Memoir.

Sandra ByrdServices: Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Fiction, creative and narrative non-fiction, memoir, devotionals.

Dario CirielloServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: 1¢–4¢ per word.

Specialties: Science Fiction and Fantasy, Mystery and Crime, Romance, Literary Fiction.

Miranda DarrowServices: Developmental editing, coaching, book mapping, line editing, ghostwriting.

Rates: $.0175–$.0375 per word.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Rochelle DeansServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Query Editing, Academic Editing, Non-Fiction Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Plot structure.

Christy DistlerServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Critique.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified, but seems to lean toward Christian Fiction.

The Engaged EditorServices: Developmental editing, line editing, proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Joshua EssoeServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Genre Fiction, Fantasy, Science Fiction, Horror.

Elizabeth EvansServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Assessment, Proposal Crafting and Editing, Ghostwriting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Lorna FergussonServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Appraisals.

Rates: £275–£800+, depending on service and length of project.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Free ExpressionsServices: Comprehensive editing.

Rates: $425–$3,875 per 1,000–100,000 words.

Specialities: Fiction, picture books.

Annette M. IrbyServices: Critiquing, copyediting, proofreading, substantive editing.

Rates: $7–$9.50 per page.

Specialities: Christian fiction.

Don JanalServices: Coaching, developmental editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Non-fiction.

Jessi’s Profressional Book EditingServices: Developmental editing, line editing, copyediting, manuscript evaluation, coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Non-fiction, memoir, biography, historical fiction, literary fiction, thriller, mystery, science fiction, fantasy, Christian, young adult, children’s fiction, women’s fiction.

Caroline KaiserServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Line Editing, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Mystery, Thriller, Historical Fiction, Children’s Fiction, Young Adult, Fantasy, Science Fiction.

Nicole KlungleServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $2–$3 per standard page.

Specialties: History, Humor, Writing Instruction, Memoir, Literary Fiction, Paranormal Romance.

Mary KoleServices: Developmental Editing, Coaching, Outline Evaluation, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: $249–$3,999.

Specialties: Children’s Literature.

Ann KroekerServices: Coaching.

Rates: $125–$1,025.

Specialties: Unspecified.

C.S. LakinServices: Developmental Editing, Proofreading, Coaching.

Rates: $8-$10 per page.

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction.

Dana LeeServices: Proofreading, Copy Editing, In-Depth Editing, Developmental Editing

Rates: 1.4¢–4¢ per word

Specialties: Romance, Mystery, Memoir, Non-Fiction, Spanish to English books

Kurt LipschutzServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Poetry

Katie McCoachServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Science Fiction, Fantasy, Dystopian, Romance.

Leslie McKeeServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Romance.

Andrea MerrellServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Mentoring.

Rates: $30–$40 per hour.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Christian Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Victoria MixonServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Synopsis Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Novel, Short Story, Narrative Non-Fiction, Memoir.

Ginger MoranServices: Developmental Editing, Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction.

Roz MorrisServices: Developmental Editing.

Rates: £70 per 1,000 words.

Specialties: Fiction, Memoir, Non-Fiction

Robin PatchenServices: Developmental Editing, Line Editing, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $2–$7 per page.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Christian Fiction.

Lisa PoissoServices: Developmental editing, manuscript evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Arlene PrunklServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Indexing, Fact Checking.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified.

Lori PumaServices: Coaching, manuscript evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Fiction.

Revision DivisionServices: Manuscript evaluation, beta reading, line editing, copyediting, proofreading, coaching, outline evaluation, blurb revision.

Rates: 1.5¢–3¢ per word.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Bryan Thomas SchmidtServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Ghostwriting, Short Story Review.

Rates: 1¢–5¢ per word.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Jessica SnellServices: Proofreading, copyediting, developmental editing, ghostwriting.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Romy SommerServices: Manuscript, appraisal, developmental editing, copy editing, query assistance.

Rates: 1.2¢–1.8¢ per word.

Specialities: Romance, women’s fiction, historical, cosy mysteries.

Jim ThomsenServices: Line editing, copyediting, proofreading, developmental editing, coverage editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Crystal WatanabeServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Whisler EditsServices: 1:1 Coaching.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

Lara WillardServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Graphic Novels, Comics, Children’s Fiction, Picture Books, Young Adult.

Ben WolfServices: Developmental Editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialties: Unspecified but seems to favor Science Fiction.

Word Haven EditorialServices: Manuscript evaluation, developmental editing, line editing, copy editing.

Rates: Contact for rates.

Specialities: Unspecified.

The Write ProofreaderServices: Proofreading.

Rates: 2¢ per word.

Specialities: Unspecified.

The Writer’s HighServices: Development editing, line editing, manuscript evaluation, manuscript review, coaching.

Rates: 2.4¢–1.2¢ per word.

Specialities: Speculative fiction, historical fiction, mystery, literary, flash fiction, southern themes.

Linda YezakServices: Developmental Editing, Copyediting, Proofreading, Manuscript Evaluation, Coaching.

Rates: $3–$4 per page.

Specialties: Fiction and Non-Fiction.

Ginny YtrrupServices: Developmental Editing, Coaching.

Rates: 2.5¢–3.5¢ per word.

Specialties: Fiction, Non-Fiction, Web Content, Devotional, Query or Cover Letter, Book Proposal, Fiction Synopsis.

***

In today’s market, getting feedback from a skilled editor is crucial—especially if you’re planning to publish independently. If you’ve yet to find a good book editor, start with the names here and get ready to transform your story!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever worked with a good book editor? Can you add to the recommendations here? Tell me in the comments!The post Need a Good Book Editor? Top Up-to-Date Recommendations appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 16, 2025

How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character (Part 2 of 2)

One of the most exciting challenges in storytelling is writing characters who grow over time—not just within a single story, but across several. Whether you’re working on a series or revisiting a familiar protagonist in a new standalone, the question inevitably arises: How do you create different character arcs for the same character without repeating yourself? How do you honor what’s come before while still offering readers something new? In many ways, this is where character development becomes the most rewarding—when you’re not just building a compelling arc, but an evolving journey.

One of the most exciting challenges in storytelling is writing characters who grow over time—not just within a single story, but across several. Whether you’re working on a series or revisiting a familiar protagonist in a new standalone, the question inevitably arises: How do you create different character arcs for the same character without repeating yourself? How do you honor what’s come before while still offering readers something new? In many ways, this is where character development becomes the most rewarding—when you’re not just building a compelling arc, but an evolving journey.

Last month, we did a bit of exploring about how to vary your character arcs by using the Enneagram system to identify different internal conflicts for characters with different personality types. We also talked about how pairing Enneagram insights with the archetypal Life Cycle can generate arcs that are not only distinct but also deeply resonant. However, as I mentioned last week in the first installment in this two-part series, the more I sat with that discussion, the more I realized there was another layer we hadn’t fully uncovered: what happens when you’re writing different character arcs for the same character?

The reader question that originally inspired these discussions (about how to use the Enneagram’s nine types to avoid repetitive Lies the Character Believes) sparked a larger reflection, not just on personality theory, but on long-term character development. If you’re writing a series or revisiting a character across multiple stories, you’ve likely asked yourself: How do I keep this arc feeling fresh? What else can this character learn, face, or become? The challenge isn’t just variety for its own sake. Rather, it’s about honoring the integrity of your characters while continuing to push their evolution in meaningful ways.

Last week, I offered six progressive systems you can use to help you chart long-term serial character arcs. This week, I want to dig into some general principles for approaching a character’s journey as an unfolding process that stretches beyond a single arc.

In This Article:How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character: Write Different ThemesUsing Robert McKee’s Thematic SquareExploring Different Archetypal Roles (Beyond the Life Cycle)Exploring Different Backstory GhostsHow to Deeply Develop a Single Theme: Listen to Your CharactersExploring Different Inner FacetsChanging Up the Supporting CastExploring Consequences From Previous BooksEmphasizing Different EmotionsHow to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character: Write Different ThemesLet’s start by exploring the two different approaches you might find yourself in when writing multiple books. The first is the possibility that you are writing totally different character arcs for each new story. This might be because you’re writing an entirely new cast of characters and don’t want to repeat yourself; or it could be because you’re writing an episodic series in which you want to explore new plots and arcs in each installment.

In either case, the simplest rule of thumb when wanting to write different character arcs for the same character is to focus on exploring different external aspects. Basically: write a different plot. A relatively good example of this is the MCU, which featured dozens of stories set in the same story world. The series often succeeded in creating varied character arcs by offering varied or unexpected plots.

>>Click here to read The Do’s and Don’ts of Storytelling According to Marvel

For Example:

Tony Stark’s themes of escapist irresponsibility created very different themes from Peter Parker’s mistakes of teenage naivety.

Spider-Man: Homecoming (2017), Sony Pictures, Marvel Studios.

Here are a few more tools you can use to help you accomplish this variation.

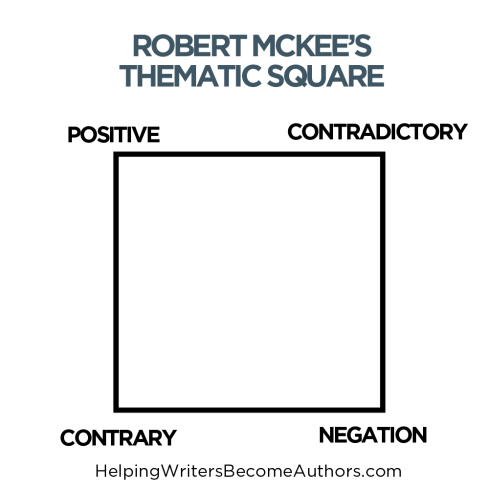

1. Robert McKee’s Thematic Square

Story by Robert McKee (affiliate link)

Plot is tied to character arc which is tied to theme. The Thematic Square is a storytelling tool created by Robert McKee in his book Story that helps writers explore theme from multiple angles by identifying not only the central value (e.g., love) and its opposite (e.g., hate), but also a contrary value (e.g., indifference) and its negation (e.g., self-hatred). In a single story, this can help you create layered moral complexity and richer character conflict. However, by exploring a different quadrant of the square in different stories, you can visit various thematic neighborhoods within the same world from story to story.

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

In addition to the continuity of the archetypal Life Cycle (which I mentioned last week and which you can read more about in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs), you can also focus on other ancillary archetypes. For example, exploring how your protagonist manifests the Trickster aspects of persoanlity in one story, the Rebel in another, and the Caregiver in still another can create opportunities for wildly different character arcs. Here’s a quick list of possibilities:

The Trickster – Brings chaos, humor, and unexpected change, often disrupting the status quo.The Ally – Supports others through trials as a loyal companion.The Shapeshifter – Changes form or allegiance, often creating doubt and intrigue.The Innocent – Seeks happiness and safety, often symbolizing purity or naiveté.The Orphan – Craves belonging and connection after experiencing loss or abandonment.The Rebel – Challenges norms and fights against injustice or oppression.The Sage – Pursues truth and knowledge, often as a detached observer.The Creator – Builds, innovates, or brings visions into reality.The Caregiver – Protects and nurtures others, often sacrificing personal needs.3. Explore Different Backstory GhostsFinally, as you seek to generate new and different character arcs throughout your series, remember that the catalyst for any character arc is the character’s backstory Ghost (sometimes called the wound). To explore different character arcs for the same character, look at different catalyzing events in your character’s past. This is a common (although often overdone) approach for TV series. When they finish one story arc and need to pursue a fresh angle, they will often reveal new and unexpected events in the characters’ pasts that link them to new conflicts.

For Example:

After wrapping up its initial storyline and associated character arcs in Season 5, Supernatural extended its run by introducing new backstory elements, notably the main characters’ reaction to secrets in their family’s past, including the fact that their mother had been a Hunter before meeting their father.

Supernatural (2005-2020), The CW.

How to Deeply Develop a Single Theme: Listen to Your CharactersWhat if you’re writing a series with an overarching plot that goes deep with a thematically cohesive character arc for your protagonist? In that case, how can you keep each story’s exploration of this overarching theme fresh and interesting, while also advancing the bigger arc?

The first thing to remember is that, in any story or series of stories, the thematic Truth a character learns (and therefore the successive Lies the Character Believes that must be overcome) exists along an ever-evolving spectrum. Therefore, even though the character may learn some version of an “ultimate” Truth by the story’s end, that Truth will be built of many smaller realizations and epiphanies along the way.

To progress that thematic throughline in a way that feels both realistic and also deep and nuanced, the most important trick is simply to listen to your characters. Really, this means listen to yourself. Listen to your own deep, innate knowing of how personal change occurs and what questions, roadblocks, sacrifices, and triumphs are likely to feel resonant along the way.

Here are a few tips and tricks for deepening your theme from book to book in a series.

1. Explore Different Inner FacetsIn any dramatic personal change (and therefore in any dramatic character arc) many different facets of the person will be affected. Depending on the length of your series, you have the opportunity to go deep with many different ways your characters are affected by the changes they are undergoing. For example, in one story you might explore how the change impacts the protagonist’s relationships, while in another you might explore how it impacts the protagonist’s experience of hope versus despair, while still another might delve into issues of ongoing personal integrity in the face of the changes the character is confronting.

2. Change Up the Supporting CastOne of the easiest ways to open new opportunities for exploring different facets of your characters is to change up the supporting cast. The thematic elements that arise from your protagonist’s interaction with a parent will be very different from the thematic elements that arise from your protagonist’s interaction with a love interest or frenemy. The only caution here is to make sure that in changing up the cast dynamics, you are not shortchanging the screentime of any key relationships that may, in fact, be the primary reason readers are there in the first place.

3. Explore Consequences From Previous BooksThe juiciest part of any series is its unparalleled ability to go deep with its own consequences. If you’re uncertain how your character’s arc might be different in a subsequent book, start by asking yourself:

What’s changed?What did the characters do or have done to them in the previous book that has consequences?How did the conclusion of the character arc in the previous book change how the character views the world or him/herself?Start pulling threads and exploring what new thematic avenues may now be open to you.

For Example:

The BBC show Poldark was particularly good at this from season to season. Its protagonist, Ross Poldark, rarely made a decision that didn’t have unforeseen but still realistic consequences. One example is his secret purchase of his cousin’s widow’s shares in his then-worthless mine, in order to gift her with needed money. When that mine later became profitable, he was accused by his nemesis of underhanded dealings in “stealing” from her.

Poldark (2015-2019), BBC One.

4. Emphasize Different EmotionsFinally, one of the easiest ways to tap into new and different character arcs for the same character is to explore different emotions. If anger predominated in one book, then perhaps joy or love may be the focus of another. If confidence and self-realization showed up in one book, then despair or disillusionment may follow. Particularly, think about how the “positive” or “negative” charge of one emotional theme can arc into its opposite. For example, in a long series, a defeat may follow a victory may follow a defeat.

Obviously, no one book should focus exclusively on a single emotion. But you can go deep with one emotion as a way of shining its particular shade of color onto the larger stage of your story’s and series’ themes.

***

Exploring different character arcs for the same character invites writers into some of the richest possibilities storytelling has to offer. It asks you to think deeply about the long-term consequences of change, how different parts of a character’s psyche can take center stage at different times, and how transformation itself evolves. Whether you’re crafting a series, revisiting an old character, or simply playing with the idea of continuity across your stories, this kind of narrative layering can open up new creative depths for both you and your readers.

In SummaryWriting different arcs for the same character requires more than just inventing new external conflicts. It demands an understanding of how transformation can unfold in complex, realistic, and meaningful ways across time. By focusing on how plot, character, and theme create and influence one another, you can gain deeper insights into how to naturally and resonantly evolve your character through multiple different character arcs.

Key TakeawaysDifferent arcs for the same character are best built around new thematic focuses and inner conflicts, as well as new plots.Tools like the Thematic Square and archetypal roles (such as Trickster and Caregiver) can offer helpful variety and depth in mapping believable inner change.Long-term character growth feels most authentic when arcs build on each other through a deep understanding of personal transformation and thematic intent.Revisiting a character can offer opportunities to explore consequences from past books, new emotional outlooks, and different relationship dynamics.Want More?

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

If you’re fascinated by the deeper structure behind character arcs—and especially how they connect to theme—check out my book Writing Your Story’s Theme. In it, I explore how character change is naturally intertwined with plot and theme. These “big three” naturally work together to create cohesive and resonant stories. Whether you’re writing standalone stories or weaving a multi-arc journey across a series, your characters’ emotional evolution is most impactful when it’s inextricably tied to the thematic heart of your story. Writing Your Story’s Theme offers a step-by-step approach to identifying, developing, and integrating theme at every stage of your story’s structure and your characters’ growth. It’s the perfect companion for writers who want their stories to resonate on every level. It’s available in paperback, e-book, and audiobook.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever written different character arcs for the same character across multiple stories? What challenges or discoveries did you encounter in keeping those arcs fresh and meaningful? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character (Part 2 of 2) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 9, 2025

How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character (Part 1 of 2)

One of the most interesting challenges of writing a series is figuring out how to create different character arcs for the same character, without it feeling repetitive or forced. Whether you’re writing a progressive arc that unfolds over several books or you’re exploring entirely different arcs in each installment, the goal is always to keep the character’s journey fresh and meaningful.

One of the most interesting challenges of writing a series is figuring out how to create different character arcs for the same character, without it feeling repetitive or forced. Whether you’re writing a progressive arc that unfolds over several books or you’re exploring entirely different arcs in each installment, the goal is always to keep the character’s journey fresh and meaningful.

Last month I shared a post about developing different character arcs using the Enneagram personality system. However, after writing that post (and its follow-up about how to unite the Enneagram with the archetypal Life Cycle for even deeper character arcs), I realized I hadn’t quite got to the heart of the question that inspired that original post, from Zoe Dawson:

What is your take on using the Enneagram nine personality types and constructing their Lies so that it’s not repetitious for each story?

Although Zoe’s question was specifically about the Enneagram, the deeper underlying dilemma is one any author writing more than one story will eventually face: How can you make sure you’re writing varied and interesting character arcs—rather than just repeating yourself?

This quandary may ring true in a number of different scenarios:

You’re writing a series in which each book features progressive character arcs that all tie into a larger overarching arc.You’re writing a series that features a thematically new and independent character arc for each story.You’re writing multiple unrelated books and want each one to be fresh and different.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

Today, I want to dig deeper into the big picture of how to construct Lies the Character Believes, character arcs, and themes that don’t repeat from story to story. This week, we’ll dig into some specific tools and frameworks that can help you shape varied arcs; next week, we’ll explore some general principles to keep in mind.

To get us started, here’s an idea I’ve always found resonant and that can be helpful to keep inmind when seeking to vary your writing:

We all have one story to tell and we just go on telling it in different ways.

Now, is that explicitly true?

Certainly not.

I, for one, have written one novel after another that is completely different from one another. And yet, I do feel that every story in an author’s body of work must ultimately point to the deeper truths and themes of the foundational story that is the author’s own life. No matter how much you may (or may not) change the outer trappings in your story (genre, setting, plot focus, etc.), the underlying thrust and focus will always be you.

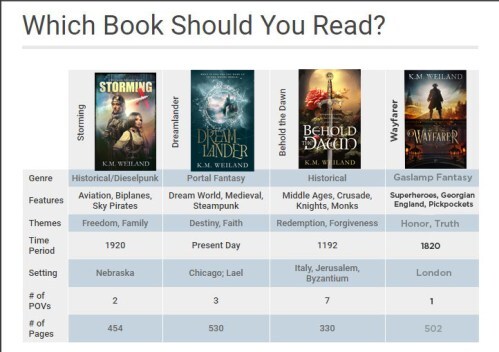

Click to enlarge.

I don’t see this as a drawback. I see it as the most compelling offering every author brings to their readers. In fact, I would suggest you might be most successful in varying your character arcs across books once you can realize the thrust of your own underlying interest and intention. For example, no author was perhaps more famous for writing a legion of staggeringly quirky and unique characters than Charles Dickens, yet even a cursory familiarity with his stories shows the underlying cohesion of the author’s focus on social issues, particularly the plight of the city’s poor. As you brainstorm new and different character arcs for your stories, it might be worthwhile to start by first identifying what actually makes them the same.

Little Dorrit (2008), BBC / WGBH Boston.

In This Article:6 Progressive Personalities and Development Systems to Write Different Character ArcsThe Five Foundational Character ArcsThe Life Cycle of Archetypal Character ArcsEnneagram Map of HealthSpiral DynamicsThe Four Stages of AlchemyThe Four Stages of Knowing6 Progressive Personality and Development Systems to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same CharacterLet’s start where this question is trickiest: How to write different character arcs for the same character?

One powerful way to write different character arcs for the same character is to ground the character’s growth in a larger developmental framework. Just like real people, characters evolve through recognizable stages—emotionally, psychologically, and even spiritually. Mapping your characters’ journeys to a progressive system can offer a shortcut for creating arcs that feel both fresh and cohesive across a series.

The following models can offer useful blueprints for tracking your characters’ inner evolution and continuing to shift the lens through which they experience the world.

1. The Five Foundational Character Arcs

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

The basic “shape” of foundational character arcs can, in themselves, guide you to resonant variations. These foundational arcs (which I talk about in-depth in my book Creating Character Arcs and elsewhere) are:

Heroic ArcsPositive Change ArcFlat Arc>>Click here to read more about the Heroic Arcs.

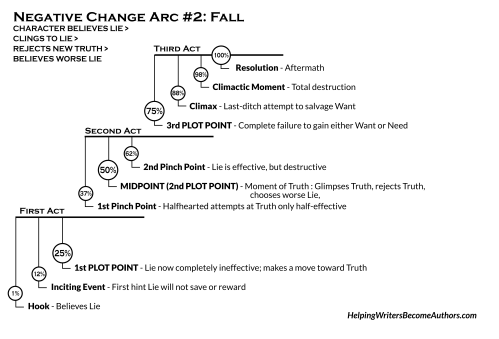

Negative Change ArcsDisillusionmentFallCorruption>>Click here to read more about the Negative Arcs.

You can mix and match these arcs from story to story to create vastly varied experiences. The simplest approach is to observe the natural connections among them, especially between the two Heroic Arcs and the three Negative Change Arcs, respectively.

The Positive Change Arc—in which the character overcomes a limited Lie-based perspective and gains a broader Truth-based perspective—leads naturally into a subsequent Flat Arc—in which the character can stand upon this newly gained Truth to inspire change in others.

Likewise, the Negative Arcs can be crafted as part of a larger cycle. The character might undergo a Disillusionment Arc—in which a difficult new Truth creates a vulnerability that may lead to resistance or resentment. This can then easily lead into a Fall Arc, in which the character bolsters resistance to the Truth by investing in greater and greater Lies. This easily leads into the still worse Corruption Arc, in which a character who once had the opportunity and advantage of recognizing the Truth instead opts to reject it utterly.

2. The Life Cycle of Archetypal Character Arcs

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

In my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs, I fleshed out the mythic lens of storytelling beyond just the Hero’s Journey to explore the full gamut of the human Life Cycle. Each of these six foundational archetypal character arcs naturally leads one into the other, making them perfect for a series in which you wish to explore an ever-maturing character.

These six foundational archetypes are:

The Maiden (Individuation)The Hero (Service)The Queen (Leadership)The King (Sacrifice)The Crone (Surrender)The Mage (Transcendence)You can find even more possibilities for variation—while adhering to a solid thematic throughline—by also exploring the six Flat archetypes and the twelve shadow archetypes that accompany each of the primary archetypes.

Graphic by Joanna Marie Art.

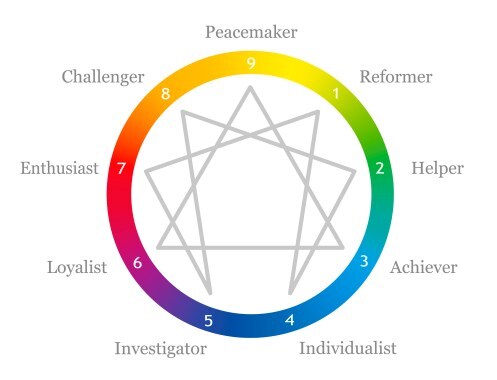

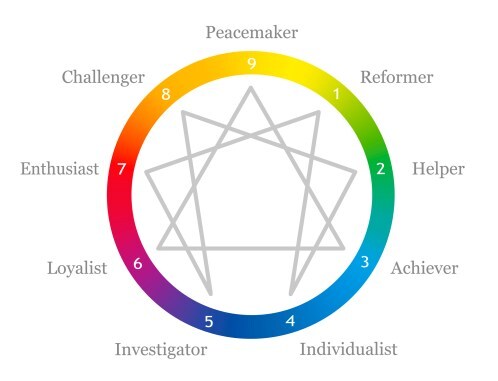

3. Enneagram Map of Health

Personality Types by Don Richard Riso and Russ Hudson (affiliate link)

Last month, I offered quite a few new tools and perspectives for using the Enneagram personality system to develop your character arcs. One particularly useful aspect I did not touch on was the stages of growth inherent to each type. In their book Personality Types, Don Richard Riso and Russ Hudson map nine stages for each type, ranging from healthy to average to unhealthy. Each of these stages could be fleshed out into a full character arc with the stages advanced in either direction, depending on whether you wanted to ultimately tell a story of a character who changes positively or negatively.

For example, the nine stages of Type Eight (the Challenger) are listed like this (from healthy to unhealthy):

The Magnanimous HeartThe Self-Confident PersonThe Constructive LeaderThe Enterprising AdventurerThe Dominating Power BrokerThe Confrontational AdversaryThe Ruthless OutlawThe Omnipotent MegalomaniacThe Violent Destroyer4. Spiral Dynamics

Spiral Dynamics by Don Edward Beck and Christopher C. Cowan (affiliate link)

Created by Don Beck and Chris Cowan, Spiral Dynamics is a model of human development that maps how individuals and societies evolve through increasingly complex value systems. Each stage—represented by a color—reflects a particular worldview, from basic survival to tribal loyalty to achievement and beyond. In character development, Spiral Dynamics can help you explore how a character’s core motivations and beliefs shift over time. As they move up (or regress down) the spiral, they may adopt new values, question old assumptions, or clash with characters operating from different stages, all of which can offer rich material for varied arcs across a series.

The currently recognized stages or “memes” of the spiral are:

Beige (SurvivalSense): Basic survival priorities (e.g., food, water, shelter, safety).Purple (KinSpirits): Tribal loyalty, superstition, tradition.Red (PowerGods): Dominance, ego, power, and asserting control over others (also called the Warlord meme).Blue (TruthForce): Order, rules, morality, and obedience to a higher purpose or authority.Orange (StriveDrive): Achievement, success, science, and rational progress.Green (HumanBond): Equality, empathy, community, and consensus-driven values.Yellow (FlexFlow): Integration, systems thinking, flexibility, and personal responsibility.Turquoise (GlobalView): Holistic awareness, unity, and spiritual consciousness.5. The Four Stages of AlchemyOriginally developed in the Middle Ages as a supposed process of turning lead into gold, the stages of alchemy are now recognized as a symbolic representation of … you guessed it, character arcs! (Aka, psychological development. Potato. Potahto.) A few years ago, I shared a post showing how the four stages of alchemy map perfectly onto the four quarters of story structure and, therefore, character arc. However, you can also choose to represent each stage as an entire arc of its own, allowing a four-story cycle to reveal the final alchemy. For that matter, many explorations of alchemy posit many more stages than just four, which could allow you to both lengthen and deepen your story arc.

The four basic stages of alchemy are:

The Nigredo (The Blackening): Descent into darkness, confusion, breakdown, ego death.The Albedo (The Whitening): Purification and clarity, recognizing truth, separating from illusion.The Citrinitas (The Yellowing): Insight, illumination, integration, growing wisdom.The Rubedo (The Reddening): Wholeness, rebirth, final transformation into the true self.6. Four Stages of KnowingEarlier this year, I similarly explored how the popular “four stages of knowing” also map neatly onto the four quadrants of a story’s development. Just as with the alchemical process, you can also stretch these stages to explore each aspect of the transformation more deeply in multiple evolving character arcs.

The Four Stages of Knowing are:

Not Knowing That You Don’t Know: Unconscious ignorance.Knowing That You Don’t Know: Conscious ignorance.Not Knowing That You Know: Unconscious competence.Knowing That You Know: Conscious competence.***

All of these frameworks—whether psychological, mythic, philosophical, or symbolic—can offer powerful scaffolding for exploring different character arcs for the same character without losing cohesion or authenticity. Not only can they help you avoid repetition, they can also support you in uncovering the deeper throughline of meaning that connects your stories to each other—and to you!

Next week, we’ll zoom out for a big-picture look at some guiding principles and narrative strategies you can use to vary your character arcs across multiple books or series. We’ll explore how to make your arcs feel intentional and fresh without straying too far from the heart of what makes your storytelling uniquely yours. Stay tuned!

In SummaryWhen writing multiple stories—whether within a series or across a body of work—one of the most powerful ways to ensure fresh and meaningful character arcs is to root them in the natural evolution of human development. By drawing on progressive models like the five foundational arcs, archetypal Life Cycle, Enneagram growth stages, Spiral Dynamics, and other systems, you can create nuanced journeys that build upon one another rather than repeat. Recognizing your own thematic throughline as an author only deepens the authenticity of these arcs. Next week, we’ll look at broader storytelling principles that can help you vary arcs across books, even outside of progressive systems.

Key TakeawaysRepetition in character arcs is a common challenge for writers of series or multiple books, but it can be overcome with intention and structure.

Developmental models like the five foundational character arcs or the archetypal Life Cycle can offer a roadmap for evolving your character’s journey meaningfully across books.

The Enneagram and Spiral Dynamics can offer deep personality and value-system frameworks that naturally lend themselves to transformation over time.

Alchemy and symbolic systems can add depth and metaphorical resonance to character progression.

Discovering your own thematic signature as an author can be a compass for creating unique yet unified arcs across your body of work.

Want More?

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

If you’re looking to deepen your understanding of character development and ensure your cast evolves in meaningful, thematically resonant ways, my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs offers a powerful framework. It explores six foundational arcs—Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, and Mage—that reflect universal patterns of growth and transformation. Whether you’re crafting a protagonist’s journey or exploring contrasting arcs for supporting characters, this resource can help you weave rich, symbolic layers into your storytelling. It’s perfect for anyone wanting to write dynamic character arcs for different characters across a standalone novel or an entire series. It’s available in paperback, e-book, and audiobook.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you approach writing different character arcs for the same character in a series or across multiple books? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Write Different Character Arcs for the Same Character (Part 1 of 2) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

June 2, 2025

The Danger of Overexplaining in Dialogue—and How to Avoid It

Note From KMW: This week’s post is a quick one—but it covers a sneaky little habit that can creep into even the best of stories: overexplaining in dialogue. I’ve seen it in books I’ve read, and I’ve definitely caught myself doing it too. It’s easy to do when we want to make sure readers really understand what’s going on, but often, this dialogue mistake just ends up slowing the story and undercutting our characters.

Note From KMW: This week’s post is a quick one—but it covers a sneaky little habit that can creep into even the best of stories: overexplaining in dialogue. I’ve seen it in books I’ve read, and I’ve definitely caught myself doing it too. It’s easy to do when we want to make sure readers really understand what’s going on, but often, this dialogue mistake just ends up slowing the story and undercutting our characters.

If you’ve ever wondered whether you’re trusting your readers enough, this one’s for you! The post was inspired by an example so bad I’m paraphrasing rather than directly quoting it. :p I’ll be back next week with a longer post (and podcast), the first in a two-part series I’m really excited about. Stay tuned!

***

As writers, we work hard to earn our readers’ trust. Nothing shatters that trust faster than treating them like they’re not smart enough to keep up. One of the most subtle and common ways authors do this is by overexplaining in dialogue. This usually doesn’t happen intentionally, but out of the fear readers won’t “get it” unless you spell it out. Unfortunately, when you overexplain or repeat yourself, especially in dialogue, readers can feel like the story is talking down to them or even, simply, below their level. That’s a fast track to losing their interest.

Consider a fantasy novel I once read. The author wrote some good dialogue that effectively explained situations while also conveying attitude, nuance, and subtext. Unfortunately, she submarined the dialogue’s inherent buoyancy by having the narrating character explain everything that was said, almost to the point of paraphrasing the dialogue.

For example, in one particular scene, the narrator worried another character might react violently if awoken. This was made clear in the narrative, then repeated, almost word for word, in an immediately subsequent dialogue exchange. The story was otherwise a smart, funny romp. But the author’s penchant for explanation added deadweight that slowed the book down and made me, as a reader, want to start skimming.

Here’s a paraphrased example of how dialogue that repeats the narrative (and vice versa) can feel condescending to readers:

Marcella hesitated outside the bedroom door, clutching Marcus’s supper with both hands. Her fingers tightened around the clay bowl. The last time she’d tried to wake Marcus when he was having one of his episodes, he’d come up swinging—half-conscious and convinced she was someone else. She’d ended up with a sprained wrist and a bruised cheek.

She looked at Angelina. “I don’t think I should go in there,” she whispered. “Last time he had one of these nightmares, he thought I was someone else and attacked me. I hurt my wrist pretty badly.”

This version needlessly repeats the same information in both the narrative and the dialogue. The reader is told twice about Marcus’s violent outburst and the character’s fear—without any additional depth or emotional layering. It slows the pace and makes Marcella sound like she’s explaining the situation not to another character, but to the readers—as if the author doesn’t trust them to retain or interpret what they just read.

The best fiction respects the intelligence of its readers. When your narrative and your dialogue work together, rather than redundantly repeating each other, you create a more immersive, efficient, and respectful reading experience. Before you hit publish, take a pass through your dialogue scenes and ask yourself: “Am I letting the story speak for itself, or am I explaining things that are already clear?”

Trust your readers. They’re smarter than you think—and they’ll thank you for believing it!

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever caught yourself overexplaining in dialogue—or spotted it in a book you were reading? Tell me in the comments!The post The Danger of Overexplaining in Dialogue—and How to Avoid It appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 26, 2025

Crafting Archetypal Arcs With Enneagram Insights

Note From KMW: Before we get started today, this is just a quick note to let you know that today is the final day you can save 25% off my entire store during my Memorial Day weekend sale. This includes all the e-books, workbooks, courses, and brainstorming guides. If you need some new writing tools, now’s a great time!

Note From KMW: Before we get started today, this is just a quick note to let you know that today is the final day you can save 25% off my entire store during my Memorial Day weekend sale. This includes all the e-books, workbooks, courses, and brainstorming guides. If you need some new writing tools, now’s a great time!

***

The Enneagram is often thought of as a personality system, but at its heart, it is an archetypal map of human motivation and transformation. Each of its nine types represents a universal pattern of behavior rooted in deep emotional truths (what we, as storytellers, might think of as thematic Truths). Like the Life Cycle of archetypes I explore in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs, the Enneagram reflects the evolving inner journeys we all undertake throughout our lives.

Although this archetypal similarity makes the Enneagram and the six Life-Cycle archetypes intuitive partners, it can also be difficult to sort the complexity of the two systems in a way that is actually useful for developing characters. Last week, we explored some of the innumerable possibilities for character-arc variation available within each Enneagram type. This week, I’m answering another reader question—from Elisheva–that points to this central conundrum of combining the Enneagram with the archetypes of the Life Cycle:

I love archetypes and I love the Enneagram, but when I try to use both tools when writing a story I get confused about how they interact. Both of them have their own Lies and conflict dynamics. And yet, they both are true. As a person, we go through the archetypical life stages, but we also have our personality to contend with. So, essentially, we are juggling the Lies and conflicts that come with each stage while also juggling the Lies and conflicts from our innate natures. How does this work when writing a story, so as not to confuse ourselves and others and get tangled in a conglomeration of themes, Lies, and conflicts—but to have it come through cohesively?

The shortest answer is that you don’t need to understand or combine both systems in order to create dynamic and dimensional characters. Often, the simplest approach is best, in which case focusing on either an archetypal approach or an Enneagram approach might be best. However, if you enjoy the complexity of examining how different systems combine to reveal even deeper insights into human behavior, then this is your stop!

In This Article:What Happens When You Combine Archetypal Arcs With Enneagram Insights?Enneagram Lies for the 6 Archetypes of the Life CycleType 1: The ReformerType 2: The HelperType 3: The AchieverType 4: The IndiviudalistType 5: The InvestigatorType 6: The LoyalistType 7: The AdventurerType 8: The ChallengerType 9: The PeacemakerBest Fit Enneagram Types for Each ArchetypeWhat Happens When You Combine Archetypal Arcs With Enneagram Insights?As I’ve explored in other posts (linked below), the Enneagram is a system of nine archetypal personality types, each representing a different core motivation and strategy for navigating the world. It maps surface behaviors, as well as the deep emotional patterns that drive our actions, fears, and desires. Unlike many personality systems, the Enneagram charts a path of growth, showing how individuals can evolve toward their healthiest, most integrated selves—or fall into patterns of stress and fixation.

>>Click here to read 5 Ways to Use the Enneagram to Write Better Characters

>>Click here to read 9 Positive Character Arcs in the Enneagram

>>Click here to read 9 Negative Character Arcs in the Enneagram

>>Click here to read Enneagram Types for Writers: Types 1-4

>>Click here to read Enneagram Types for Writers: Types 5-9

>>Click here to read Avoiding Repetition for Lies Each Type Might Believe

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

Similarly, the archetypal Life Cycle I explore in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (and the Archetypal Character Guided Meditations) charts the universal phases of transformation we experience as we move through life. From the individuation of the Maiden, through the personal expansion of the Hero, the leadership of the Queen, the sacrifice of the King, the acceptance of the Crone, and the surrender of the Mage, the cycle demonstrates how archetypal energies evolve as we mature, confront challenges, and step into new roles within both our inner landscapes and our outer lives.

Combined, these two systems offer a richly layered view of human development. The Enneagram helps us understand the why behind our individual journeys (i.e., our motivations, blind spots, and inner work), while the archetypal Life Cycle provides a broader view of the when (i.e., the inevitable seasons of growth and change we all encounter). Together, they can create a powerful framework for writing deeper characters, as well as living more conscious, authentic lives.

Enneagram Lies for the 6 Archetypes of the Life CycleWhat follows is, as ever, a limited and subjective list of suggestions for how the themes of the Life Cycle and the Enneagram may mingle. My hope is that it will spark your own intuitive knowing about these deep archetypes, so you can find your own best interpretations for your characters and stories.

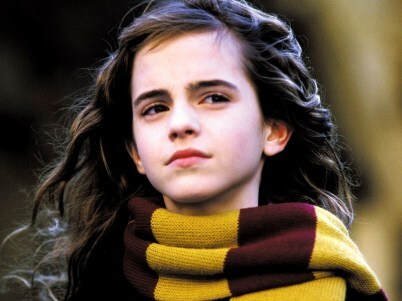

Type 1: The ReformerCore Lie: “I must be good to be worthy.”

Maiden’s Lie: “I must always be perfect to earn a place in the world.”

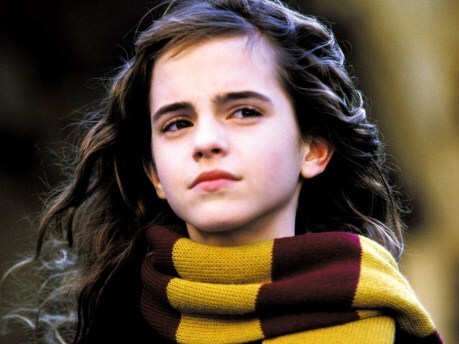

Book/Movie Example: Hermione Granger (Harry Potter) constantly seeks academic perfection to prove herself, but must individuate beyond the system of authority to learn which rules are worth breaking.

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), Warner Bros.

Hero: “I can only defeat evil if I never make mistakes.”

Theoretical Example: A police cadet learns that true bravery lies not in flawless actions, but in showing up and serving despite imperfections.

Queen: “Leading means upholding impossible moral standards.”

Book/Movie Example: Jean Valjean (Les Misérables) burdens himself with living a perfectly moral life after his redemption.

Les Miserables (2018-2019), BBC One.

King: “I must be flawless to maintain my authority.”

Theoretical Example: A legendary mob boss, feared and respected for his rigid moral code and flawless control, must face the devastating truth that his need to be untouchable is tearing his empire apart.

Crone: “I failed in life because I was never perfect enough.”

Book/Movie Example: Judge Danforth (The Crucible) struggles to evolve with the times, clinging to his rigid beliefs and refusing to acknowledge his mistakes.

The Crucible (1996), 20th Century Fox.

Mage: “True wisdom is reserved for the flawless.”

Theoretical Example: A beloved professor, on the brink of retirement during a critical crisis facing his school, must confront his fear of leaving his students vulnerable and step back to let them take charge, trusting that their own mistakes will lead to the growth they need—while he comes to terms with the fact that his time as their guiding force has ended.

Core Lie: “I must earn love through service.”

Maiden: “If I am not useful, I will be abandoned.”

Theoretical Example: A young woman on the brink of adulthood believes she must constantly care for others and meet their emotional needs, even it means sacrificing her own dreams.

Hero: “I can only save others by sacrificing myself.”

Theoretical Example: A young paramedic, eager to prove his bravery and worth in service to his community, believes he must always be the first to respond to emergencies, even at the cost of his own well-being.

Queen: “I must care for everyone, even at the cost of my own needs.”

Movie Example: Mufasa (The Lion King) rules with compassion, but his inability to fully confront and neutralize the threat posed by his brother reveals his failure to assert the tough authority needed to protect the kingdom.

The Lion King (1994), Walt Disney Pictures.

King: “Real authority is earned by serving everyone else first.”

Theoretical Example: A veteran football coach, beloved for always putting his players first, must confront the painful truth that his need to be needed is holding the team back—and that the greatest act of service might be letting someone else lead.

Crone: “Without someone to care for, I have no purpose.”

Theoretical Example: A retired teacher, disheartened by the loss of her former vitality, is coaxed back into the community by a group of former students. She must reconcile with her own aging and accept that her contribution may now look different.

Mage: “Wisdom means knowing how to fix everyone’s pain.”

Theoretical Example: An aging master carpenter, watching his apprentices struggle with the pressures of their craft, must confront his deep need to fix their problems and allow them to endure the pain of their mistakes in order to grow into their own skill and wisdom.

Core Lie: “My worth depends on what I accomplish.”

Maiden: “I must earn the approval of my authority figures.”

Theoretical Example: A high school senior, eager to prove herself, constantly overextends her commitments and sacrifices her personal needs to earn the approval of her teachers and parents, believing her worth is defined by their recognition.

Hero: “I must win at all costs to prove my worth.”

Movie Example: Lightning McQueen (Cars) believes winning races is his only value.

Cars (2006), Walt Disney Pictures.

Queen: “My reign will only be respected if I am admired.”

Movie Example: Regina George (Mean Girls) seeks admiration above authentic leadership.

Mean Girls (2004), Paramount Pictures.

King: “My value lies in my success and productivity, so I must stay in control and maintain my position, even when it’s no longer serving the greater good.”

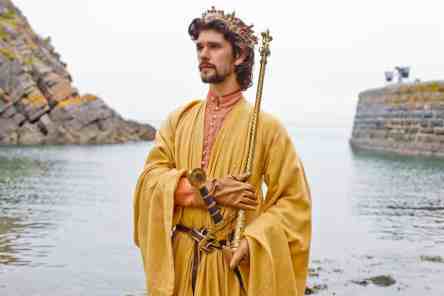

Play Example: Shakespeare’sRichard II clings to his throne, seeking personal validation and glory, but is ultimately forced to sacrifice his throne for the greater good of the kingdom when he realizes his inability to lead effectively has caused more harm than good.

The Hollow Crown (2012-2016), BBC Two

Crone: “Without accomplishments, I am nothing.”

Book/Movie Example: Miranda Priestly (The Devil Wears Prada) clings to her influence and refuses to advance her loyal employees.

The Devil Wears Prada (2006), 20th Century Fox

Mage: “I must prove my worth by making sure others succeed according to my standards, or I will be seen as ineffective or irrelevant.”

Theoretical Example: After decades of groundbreaking work, a renowned scientist hesitates to retire, fearing that stepping back will make his life’s achievements seem less significant if the next generation surpasses him.

Core Lie: “I must be unique to be significant.”

Maiden: “I must be unique and different to be truly valued, and if I don’t stand out, I’ll never be understood.”

Theoretical Example: A sheltered artist, struggling to believe her voice matters in a noisy world, is unsure how to break free from the expectations placed on her by family and society.

Hero: “I must prove my worth through my struggles and pain, or I will never truly be seen as special or important.”

Theoretical Example: A struggling musician determined to make it big must learn that personal growth comes not just through artistic expression, but by accepting himself and others.

Theoretical Example: A compassionate community organizer fears that if she imposes responsibility on others, she will be misunderstood and rejected for being too rigid or impersonal.

King: “My uniqueness sets me apart from everyone, including those I lead.”

Theoretical Example: An aging founder of a successful nonprofit, believing his uniqueness is what made the organization thrive, fears his departure will cause the loss of his individuality and the purpose he’s created.

Crone: “I was always too different to truly matter.”

Book/Movie Example: Miss Havisham (Great Expectations) isolates herself after heartbreak.

Great Expectations (2012), Lionsgate.

Mage: “My wisdom is irreplaceable, and no one else can truly understand my unique insights.”

Theoretical Example: A once-celebrated maestro watches his protégés follow their own unconventional paths, overcoming his fear that if he doesn’t guide every decision, his unique vision and legacy will be forgotten.

Core Lie: “I have to protect my energy and stay self-sufficient.”

Maiden: “I must have all the answers and fully understand everything before I can be valued or take action.”

Theoretical Example: A refugee teenager feels she must handle every challenge on her own, fearing that asking for help would put her at the mercy of unfeeling authorities.

Hero: “I can’t act until I know everything.”

Theoretical Example: A young environmental activist believes that to make a real difference, he must single-handedly lead every initiative and never show vulnerability, fearing that depending on others will expose his lack of knowledge or authority.

Queen: “Leading requires complete control over information.”

Theoretical Example: A respected scholar must come to terms with the limitations of her intellect and find a balance between reason and the emotional needs of others, ultimately discovering that leadership requires vulnerability.

King: “I must hold onto control at all costs because if I let go, everything will fall apart and no one will be able to manage without me.”

Theoretical Example: A long-serving mayor of a small town struggles to step down, convinced that without his detailed knowledge of the community’s history and past decisions, the town’s future will unravel.

Crone: “My worth ended when I stopped learning new things.”

Book/Movie Example: Ben Weatherstaff (The Secret Garden) is initially withdrawn and resigned to his age and solitude, but must learn to open up and connect with the younger generation.

The Secret Garden (1993), Warner Bros.

Mage: “True mastery requires total detachment.”

Theoretical Example: An admiral who has led his fleet through countless battles must now nurture younger officers as they begin to oversee their own missions.

Core Lie: “Security must come from the outside.”

Maiden: “I can’t trust myself; someone else must guide me.”

Movie Example: Rapunzel (Tangled) clings to Mother Gothel’s authority even as she grows suspicious.

Tangled (2010), Walt Disney Pictures.

Hero: “I must rely on rules and authorities to survive.”

Theoretical Example: During the American Revolution, a young militia leader, determined to prove his worth in battle, hesitates to take command in the face of danger, fearing that if he fails, he will not only let down his comrades but prove he was never truly fit for leadership.

Queen: “The crown is safest when I control everyone’s loyalty.”

Theoretical Example: A new President, obsessed with maintaining unwavering loyalty from every member of her Cabinet, begins to micromanage their actions and decisions, believing any hint of dissent could unravel the entire country.

King: “I must eliminate all threats to maintain stability.”

Theoretical Example: A seasoned detective, revered for keeping his city safe through rigid oversight and paranoia, begins to unravel his own team with distrust and overreach, forcing him to realize that his need to control every threat is eroding the stability he built and that stepping aside is the only way to restore trust.

Crone: “I only mattered when others needed me for advice and support.”

Theoretical Example: An aging fairy godmother, long retired and forgotten, sinks into despair believing her worth ended when the kingdoms no longer needed her contribution—until a young, reckless princess unexpectedly seeks her out, forcing her to confront her fear of irrelevance and rediscover a deeper purpose in passing on her wisdom.

Mage: “True wisdom comes only from following tradition.”

Theoretical Example: An experienced blacksmith who has spent decades perfecting his craft allows his apprentice to explore modern advances.

Core Lie: “Pain must be avoided at all costs.”

Maiden: “I can’t commit to anything serious because if I do, I’ll be stuck and miss out on all the exciting possibilities life has to offer.”

Play/Book/Movie Example: To avoid sorrow and responsibility, Peter Pan (Peter Pan) refuses to grow up.

Peter Pan (2003), Universal Pictures.

Hero: “Winning means staying one step ahead of pain.”

Movie Example: Tony Stark (Iron Man) masks his trauma with wit and invention.

Iron Man 2 (2010), Marvel Studios.

Queen: “If I take on too much responsibility, I’ll lose my freedom and the joy of spontaneity that I crave.”

Show Example: Louis XIII (The Musketeers) refuses to face the mounting pressures of his reign, instead distracting himself with pleasures and escapism, believing that avoiding harsh realities will protect him from the pain of responsibility and prevent his kingdom from unraveling.

The Musketeers (2014-2016), BBC One

King: “If I step down, I’ll miss out on all the excitement and adventure, and my life will lose its purpose.”

Theoretical Example: The aging sheriff of a small frontier town refuses to retire, convinced that without the daily thrill of chasing outlaws and dispensing justice, his life will become empty and meaningless.

Crone: “If I stop chasing fun, I’ll face regret.”

Theoretical Example: In her twilight years, a once-vibrant grandmother convinces herself that if she keeps distracting herself with new hobbies and adventures, she can stave off the emptiness that comes with facing her mortality.

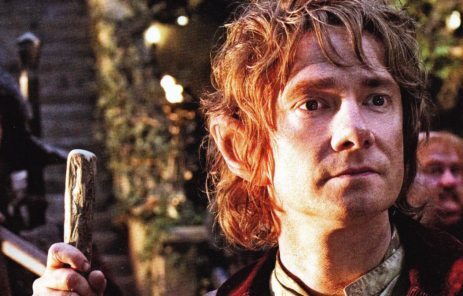

Mage: “I must keep my proteges entertained and excited with new ideas and challenges, or they’ll lose interest and never grow into their full potential.”

Book/Movie Example: Gandalf (The Lord of the Rings) sometimes feels the need to inject excitement and challenge to keep people engaged, especially during moments of stagnation.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), New Line Cinema.

Type 8: The ChallengerCore Lie: “Vulnerability equals weakness.”

Maiden: “If I don’t stay tough and in control, the world will crush me before I get the chance to grow up.”

Show Example: Haunted by the loss of her mother and consumed by shame over a secret mistake, a young Beth Dutton (Yellowstone) learns to weaponize her vulnerability—driving away Rip, the boy who loves her, believing that needing anyone will only lead to more pain and make her unfit to carry the Dutton legacy.

Yellowstone (2018-2024), Paramount Network.

Hero: “Victory demands total dominance.”

Book/Movie Example: Achilles (Troy) prioritizes glory over collaboration.

Troy (2004), Warner Bros.

Queen: “I must crush weakness to lead effectively.”

Movie Example: Princess Leia (Star Wars) believes that if she doesn’t keep absolute control over the Rebellion and shield everyone with her strength, everything she has built will fall apart.

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

King: “Power must be protected at all costs.”

Theoretical Example: An ancient dragon-king refuses to name a successor, believing that if he releases his hold on the throne, chaos will consume the realm and erase everything he’s built.

Crone: “If I show any weakness now, the world will forget me.”

Theoretical Example: An aging private investigator, weary from years of solving crimes, struggles with the belief that if she doesn’t stay ahead of everyone, she’ll be left behind and forgotten.

Mage: “If I don’t control everything around me, everything will fall apart.”

Theoretical Example: A dying inventor must accept that without his direct involvement, the future of art and science will fall into the hands of the next generation—whether they are ready or not.

Core Lie: “My presence creates conflict.”

Maiden: “If I assert myself, I’ll anger those in authority.”

Movie Example: Cinderella (Cinderella) silently endures mistreatment to preserve fragile peace with her step-family.

Cinderella (2015), Walt Disney Pictures.

Hero: “Keeping the peace is more important than fighting for what’s right.”

Book/Movie Example: Frodo Baggins (The Lord of the Rings) hesitates to act against Gollum despite danger.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), New Line Cinema.

Queen: “A ruler must maintain harmony at any personal cost.”

Theoretical Example: A single mother must reconcile with her teenage son’s drug use and her struggle to impose discipline.

King: “Leadership means erasing my own desires.”

Theoretical Example: An aging carnival owner, long seen as the heart of a beloved traveling show, must confront the truth that true harmony sometimes means letting go.

Crone: “My life mattered only when I avoided conflict.”

Theoretical Example: A retired diplomat refuses to enter the fray again even though she is needed.

Mage: “Wisdom is found only in silence and noninterference.”

Book/Movie Example: Professor Dumbledore (Harry Potter) initially withholds vital truths, believing noninterference safest.

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix (2007), Warner Bros.

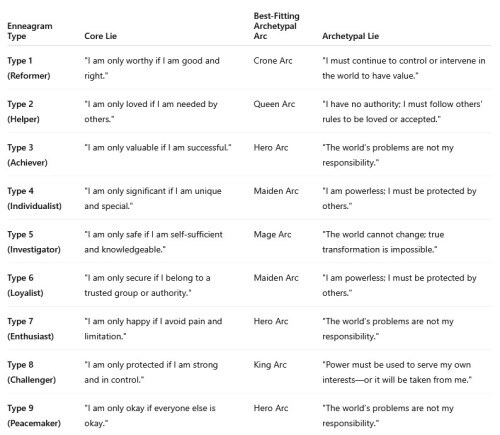

Best Fit Enneagram Types for Each ArchetypeUnderstanding which Enneagram types align best with each character archetype can offer further insights for writers looking to craft psychologically resonant stories. Below, we’ll explore which Enneagram types can be the best fit for each of the six major archetypal arcs. As seen above, every Enneagram type will have the opportunity to embody each part of the archetypal Life Cycle. However, for the purposes of storytelling, certain Enneagram types more obviously align with the innate themes of certain life archetypes.

Click for a larger view.

1. Maiden ArcThe Maiden represents youth, innocence, and the early stages of growth. This archetype often involves a journey of self-discovery, in which the character confronts fears of inadequacy.

Suggested Best Fits:Type 2 (The Helper): Twos seek external validation and approval, often believing they must be useful to be loved or accepted. This aligns with the Maiden’s journey of proving her worth.

Type 4 (The Individualist): Fours often feel like outsiders and believe they’re too different or broken to belong. This aligns with the Maiden’s struggle to find her place.

Type 6 (The Loyalist): Sixes struggle with self-doubt and trust issues. This aligns with the Maiden’s early dependence on others.

2. Hero ArcThe Hero is the archetype of the individual who goes on a quest to prove himself, often facing trials that push him beyond his limits. This arc typically involves growth through challenges and the development of inner strength.

Suggested Best Fits:Type 3 (The Achiever): Threes are motivated by the desire to prove their worth through accomplishment. This aligns with the Hero’s need to confront the difference between authentic self-worth and success-driven identity.

Type 7 (The Enthusiast): Sevens seek excitement and avoid pain. This aligns with the Hero’s lessons in embracing hardships and responsibility, as well as the adventurousness found in many Hero stories.

Type 9 (The Peacemaker): Nines prefer to avoid conflict and maintain harmony. This aligns with the Hero’s lessons in standing up and taking action for what is right.

3. Queen ArcThe Queen archetype represents leadership, responsibility, and the balance of power with wisdom. The Queen must confront the tension between personal desires and the needs of others. She often faces internal conflict over whether to uphold idealistic values or to compromise for the greater good.

Suggested Best Fits:Type 1 (The Reformer): Ones seek perfection and uphold high moral standards. This aligns with the Queen’s responsibility to govern with justice.

Type 2 (The Helper): Twos may take on leadership roles out of a need to care for others. This aligns with the Queen’s struggle to balance the needs of the people she leads with the equal necessity for justice and fairness.

Type 3 (The Achiever): Threes are driven by a desire for success and admiration. This can align with the Queen’s desire to lead effectively while also ensuring she is loved and respected.

4. King ArcThe King is an archetype of mastery, authority, and moral leadership. Kings must balance power with compassion, making decisions that affect others, while also grappling with personal doubts about worth and legacy.

Suggested Best Fits:Type 1 (The Reformer): Ones value moral integrity while desiring to fix the world. This aligns with the King’s role as a ruler who holds the kingdom’s best interests at heart.

Type 6 (The Loyalist): Sixes seek stability and security, often taking on leadership roles when they believe they can protect others. This aligns with the King’s desire to shoulder the tremendous burden of total responsibility for his kingdom.

Type 8 (The Challenger): Eights possess a drive for control and strength; they must learn that real power comes from wisdom, not domination. This aligns with the King’s focus on authority and leadership.

5. Crone ArcThe Crone represents wisdom, reflection, and acceptance of life’s consequences. This archetype is concerned with legacy and the knowledge gained through life’s experiences.

Suggested Best FitsType 1 (The Reformer): Ones must learn to accept imperfection. This aligns with the Crone’s need to forgive herself and embrace her flaws.

Type 4 (The Individualist): Fours often feel like they are misunderstood or disconnected. This aligns with the Crone’s need to reflect on her life choices and embrace her true self.

Type 5 (The Investigator): Fives search for knowledge and detachment. This aligns with the Crone’s focus on intellectual wisdom and the perspective gained over a lifetime. Fives can also align with the Hermit archetype, the negative aspect of which the Crone struggles with in her passive shadow form.

Type 5 (The Investigator): Fives search for knowledge and detachment. This aligns with the Crone’s focus on intellectual wisdom and the perspective gained over a lifetime. Fives can also align with the Hermit archetype, the negative aspect of which the Crone struggles with in her passive shadow form.

The Mage represents mastery, transformation, and the passing of knowledge. The Mage has the wisdom and skills to guide others, but may struggle with the isolation and surrender needed in the role of mentor.

Suggested Best Fits:Type 1 (The Reformer): Ones desire to fix and improve the world through wisdom and example. This aligns with the Mage’s role as a wise leader who desires to guide the young.

Type 3 (The Achiever): Mature Threes can provide guidance to others on how to achieve success while also needing to confront their need for external validation. This can align with the Mage’s role as a mentor who passes on knowledge.

Type 5 (The Investigator): Fives are natural learners and seekers of knowledge. This aligns with the Mage’s ability to impart wisdom to others.

Understanding the best-fit Enneagram types for each archetypal character arc can offer powerful insight into your characters’ internal journeys. When you align your characters’ Enneagram-driven fears and desires with the core themes of their archetypal arcs, you create a narrative with emotional resonance and psychological depth.

Whether your character is a Hero learning to face his limitations, a Queen learning to lead with integrity, or a Crone reckoning with her past, the Enneagram can add nuance and authenticity that helps bring the character arc to life. By thoughtfully pairing archetypes with Enneagram types, you can gain a dual lens through which to craft stories that both captivate and transform.

In Summary:Both the Enneagram and the archetypal Life Cycle systems are powerful tools for understanding human motivation and transformation. When combined, they can offer a deeper layer of insight into character development. The key challenge is balancing the complex dynamics of both systems without creating confusion in the story. While it’s not necessary to merge both systems to create dynamic characters, those who enjoy complexity can use them together to enrich their writing. Each Enneagram type brings its core Lie and conflict dynamics into the phases of the Life Cycle, influencing how characters evolve.

Key Takeaways:The Enneagram provides a framework for understanding a character’s motivations, fears, and desires, while the Life Cycle tracks universal phases of transformation.Combining both systems can deepen character exploration. However, it’s important to avoid overwhelming readers with too many conflicting themes and conflicts.Focusing on one system at a time (either Enneagram or archetypal Life Cycle) is a simpler approach, but integrating both can lead to more complex and nuanced character arcs.Using the core Lies and conflicts of each Enneagram type within the phases of the Life Cycle can help to create multidimensional characters that evolve through their internal and external struggles.Want More?If you’re ready to dive deeper into your characters and their journeys, my Archetypal Character Guided Meditations can help unlock fresh insights and inspire new creative possibilities. These guided meditations are perfect for dreamzoning, brainstorming, and exploring your characters’ core motivations from the inside out.

Whether your character’s story is best suited to the archetypes of Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, or Mage, these meditations will guide you to understand the heart of your characters and bring them to life in new and exciting ways. It’s like having a personal guide to help you dig into the soul of your story! Start exploring today: Archetypal Character Guided Meditations.

Go on the journey with your characters! Check out the Archetypal Character Guided Meditations.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! How do you merge archetypal characters with the Enneagram types in your writing? Which Enneagram type fits best with the archetypes you use, and how do their core motivations shape the journey? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Crafting Archetypal Arcs With Enneagram Insights appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

May 19, 2025

Using the Enneagram for Character Development: Avoiding Repetition for Lies Each Type Might Believe