K.M. Weiland's Blog

September 8, 2025

Why All Stories Are Myth—and How They Transform Us

Stories are more than just entertainment. They’re also more than just reflections of real life. This is because, at its core, narrative is myth. Whether you’re crafting epic fantasy, gritty crime drama, or cozy rom-coms, deep archetypal patterns always echo through your characters, plots, and themes. Story is the theater of the psyche. It is a dream we collectively dream, in which each character and conflict embodies a part of ourselves. When we recognize this hidden foundation, we can tap this archetypal power to access the kind of storytelling that not only captivates readers but also transforms both their inner lives and our own.

Stories are more than just entertainment. They’re also more than just reflections of real life. This is because, at its core, narrative is myth. Whether you’re crafting epic fantasy, gritty crime drama, or cozy rom-coms, deep archetypal patterns always echo through your characters, plots, and themes. Story is the theater of the psyche. It is a dream we collectively dream, in which each character and conflict embodies a part of ourselves. When we recognize this hidden foundation, we can tap this archetypal power to access the kind of storytelling that not only captivates readers but also transforms both their inner lives and our own.

A few weeks ago, I shared a post that struck a chord with many of you—about my deep desire to witness the return of “soulful storytelling.” Specifically, I wrote about my personal dissatisfaction and even boredom with contemporary filmmaking. In that post, I talked about wanting to return to stories of subtextual depth, emotional earnestness, and goodheartedness (among other qualities). In pondering on this further via the many thoughtful exchanges I got to have with all of you in the comments section on that post, I realized there are more layers to the shifts we have seen in modern storytelling—and the next shift I believe we will soon see.

One of those layers is the tension we often feel, but perhaps do not always recognize, between hyper-realism in fiction and storytelling’s inherently mythic foundation. I’m talking about the differences between stories that dutifully mimic or even exaggerate the causality of everyday life and those that draw upon the timeless archetypal patterns of the psyche.

When asked to define “story,” we may reach for the convenient answer that story is a replication of real life. But this, I will posit, is not actually true. Throughout history, we have increasingly dressed our stories in the verisimilitude of realistic details and the self-consciousness of our minds’ inner workings. But underneath all the hyper-realism, the true and archetypal shape of story itself remains something quite mythic. It is much less a product of our conscious minds—our conscious and scientific understanding of the world’s workings and our place in it—and much more a product of our unconscious minds—our symbolic and dreaming selves.

Recognizing storytelling (no matter the genre) as inherently mythic allows us, as storytellers, to walk onto a much bigger stage. We exit the relatively small stage of the self we know—the conscious self—and enter the vastness of the self that lives beyond consciousness and therefore beyond the restricted understanding allowed by the ego.

When we approach story as something inherently mythic—an archetype that exists outside and beyond humanity’s “creation” of it as an artform—we regain the capacity to create stories that touch the deepest parts of ourselves to create not just transformation, but initiation.

In This Article:Story as a Primordial Force: The Mythic Foundation of NarrativeThe Theater of the Psyche: Every Character Is YouArchetypes as Living Forces in StorytellingStory as a Living Dream: Why All Stories Are MythStory as a Primordial Force: The Mythic Foundation of NarrativeFrom the far depths of human memory, story comes to us as a primordial force. Indeed, human memory itself is a story. Before we packaged stories for $20 mass consumption—before movies, before novels—story came to us as oral myths, ritual dramas, stone etchings, and catalysts of initiation.

Nowadays, storytelling is a highly specialized skill set. We come to sites like this one to study beat sheets and timing. We divide stories into highly specialized genres and check tropes off a list. We come to story as if it is something we can master. But in approaching story like this, we risk missing not just the deeper initiation story wants to offer each of us. We also risk missing out on the best possible stories we could be sharing with our own audiences.

I want to talk about one trend in particular that I see in modern storytelling. In itself, this trend is not problematic. But when too much emphasis is placed on it, it can create a polarized experience of story that can weaken its deeper impact. This trend, as I hinted previously, is hyper-realism. It is the trend—all but ubiquitous now—of faithfully recreating modern life on the page or the screen. In some ways, we might say it is “showing” rather than “telling.”

Again, I’m not saying this approach is wrong. I love detailed fiction that shows me the story world with such dimensionality that I’m there. I love deep POVs that faithfully mine and recreate the complexities of human interiority—everything from memory to motive.

But my feeling is that when this hyper-realism is not founded upon the deeper mythology of story itself, we often risk losing the forest for the trees. I will even go so far as to say this approach is a driving force behind the type of modern storytelling that carries characters and audiences to destinations awash with sophisticated despair or, at best, ambiguous apathy.

This is not to say mythic stories do not confront their fair portion of darkness and despair. But as I continue to study story as an archetype, it is my belief that these old stories (everything from the creation stories to The Odyssey to old folk tales like Little Red Riding Hood) speak to us, first and always, in metaphor and symbol. Certainly, as we explore the continuity with which the shape of story comes to us over the eons, I believe we can see that story itself is much more than simply a mirror of life. It is an initiatory force.

Becoming Supernatural by Dr. Joe Dispenza (affiliate link)

At the end of his book Becoming Supernatural, Dr. Joe Dispenza defined initiation:

I believe we are on the verge of a great evolutionary jump. Another way to say it is that we are going through an initiation. After all, isn’t an initiation a rite of passage from one level of consciousness to another, and isn’t it designed to challenge the fabric of who we are so we can grow to a greater potential?

Story is a symbolic map of transformation. It is a blueprint for growth and change. I wrote in the previous post about how I will never be satisfied with even one single story that does not challenge me in some way—because, for me, that is what I look for in a story experience. I look for that frisson of electricity, that tinge of awe, as I sense however faintly that I am entering an uncanny space—a wyrd space.

In the old Norse, the concept of “wyrd”—from which we get our word “weird”—indicated not just the uncanny, but the fated. In story, what I seek for myself are fated encounters. I seek shatterpoints of destiny that fracture, however slightly, reality as I know it.

The Theater of the Psyche: Every Character Is YouEvery story holds the seed of this transformational power. It doesn’t matter the medium or the genre. This potential is latent in all stories—whether about hellbent mobsters or romantic HEAs or comedic farces or historical reproductions or fantastical allegories. However, whether and how well this potential is realized depends on the author. To some extent, it depends on the author’s conscious awareness of and ability to empower the story’s mythic sub-structure. But I would say, even more perhaps, it depends on the author’s personal touchstone with the mythic subconsciousness that lives within them.

If we think of story as being like a dream, we are not too far from the truth. Story—true, deep, initiatory story—is something that arises from an inner depth existing beneath and beyond egoic consciousness. We are more likely to find these stories by “channeling” them than by trying to brainstorm them.

Like dreams, stories are innately symbolic—even, and perhaps especially, when we do not realize it. As authors, we cannot always explain where our best work comes from. Often, it may seem it does not come from us. It was given to us. We are the first to be changed by it. Indeed, we may spend the rest of our lives not quite understanding it.

Also like dreams, I believe it is useful to take one more step back from the hyper-detailed and hyper-realistic showing of fiction. Until we do so, we are likely to think our stories are peopled by a varied and dimensional cast, perhaps purposefully created by us to showcase a vast number of perspectives and lifestyles. When we go deeper, we may see instead that the deepest and most mythic stories represent a single psyche—perhaps the author’s, perhaps a bit more specifically the protagonist’s, but ultimately the collective psyche.

Some schools of dream interpretation remind the dreamer to consider that everything that shows up in a dream is you. That is, it is not your father in the dream; it is some aspect of your own psyche wearing the face of your father. The same can be said of a story. Every character in the story—indeed, everything in the story—is an aspect of one psyche. The hero, the antagonist, the love interest, the mentor—all are representations of a unified psychological perspective and experience.

The deep resonance of stories that work—stories that initiate us—is the result of this inner unity. Audiences resonate because they’re watching externalized inner conflicts of the self. If you start examining stories from this perspective, you may be amazed at what you discover.

A quite obvious example is The Lord of the Rings. I particularly remember the first time I saw the scene in Fellowship of the Ring, in which the characters flee underground into the Mines of Moria, where they awaken goblins and trolls in the darkness. In so many ways, this can be seen as a descent into the unconscious and a confrontation with the shadow monsters who reside forgotten there.

The Balrog confrontation symbolizes the psyche’s descent into shadow.” (The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), New Line Cinema.)

Another vivid example of this inner-psyche theater can be found in Hayao Miyazaki’s Spirited Away. Nearly every character in Chihiro’s journey can be read as an aspect of the self.

Her parents’ careless greed is the egoic appetite that abandons her to the unconscious.The enormous baby, Boh, is the unruly inner child who must be reparented before growth can occur.Yubaba, the domineering mistress of the bathhouse, embodies the controlling authority of the superego.Haku functions as the animus—an inner guide and companion who helps Chihiro navigate transformation.No-Face represents the shadow self: a ravenous, distorted self that can only be healed through compassion and reintegration.In this light, Spirited Away becomes not simply a fantastical coming-of-age tale, but a symbolic map of psychological wholeness.

Miyazaki’s Spirited Away shows how every story is myth: each character symbolizes an aspect of the self, from the shadow in No-Face to the inner child in Boh. (Spirited Away (2001), Studio Ghibli.)

And in a more realistic example, we can see how the various characters in Pride & Prejudice represent facets of a single psyche:

Elizabeth and Darcy embody the central tension between pride and humility, shame and love.Jane reflects openness and generosity.Lydia personifies unchecked impulse.Mr. Collins plays the part of obsequious conformity.Lady Catherine stands as rigid authority.Read this way, Austen’s novel becomes not just a social comedy but an archetypal drama of the self learning to reconcile its contradictions and move toward wholeness.

Lizzie and Darcy reflect the psyche’s struggle with pride, shame, and connection. (Pride & Prejudice (2005), Focus Features.)

Archetypes as Living Forces in Storytelling

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

For writers, one of the most useful tools for enlivening the power of mythic storytelling is to access the innate power of character archetypes.

With all things archetypal, it is crucial to interact with archetypes not as simplistic stereotypes but as living forces. Put simply: we don’t get to dictate what archetypes do. When we have truly accessed them, they tell us what they will do. When we have truly understood them, we feel it all the way down to our bones. Archetypes are dynamic energies peopling initiatory arcs. They surface in different guises but always point to universal human epochs.

As writers, we can access these forces consciously to deepen our character arcs, themes, and story arcs. The most obvious way we can work with these archetypes is to learn about them through the old stories. But they are found everywhere. I would go so far as to say they are found in every story that works. More than that, they are inherent—if perhaps latent—within each of us.

As human beings (and especially as human beings with active imaginations), we already have a deep understanding and recognition of these archetypal forces—if we are brave enough to face them. This cannot be taken for granted. It can often feel much easier to ignore the call of initiation and transformation. Cutting the journey short before we finish the Dark Night of the Soul can often seem wiser. Ironically, remaining cozy and cynical in the affirming arms of despair can feel much safer than daring to keep walking into the unknown of transformation.

What archetypal storytelling—mythic storytelling—demands of us as storytellers is that we face the archetypes themselves with authenticity and with humility. Mythic storytelling demands that we listen to the deepest, loudest, softest truths within us. We know when what we are writing is mythic and archetypal—whether we call it that or not. We know when what we are writing is the truest thing it is possible for us to write. We know in our hearts. And I do not say “hearts” lightly. The heart is a much better storyteller than the head.

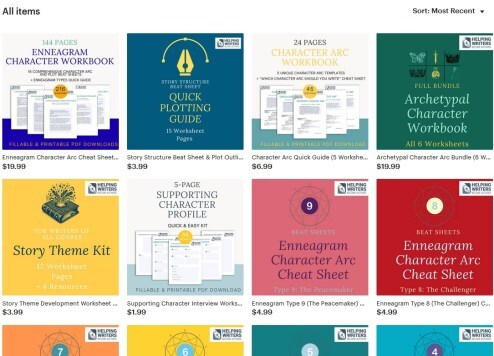

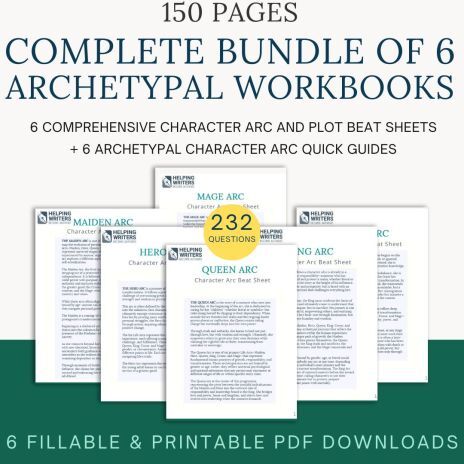

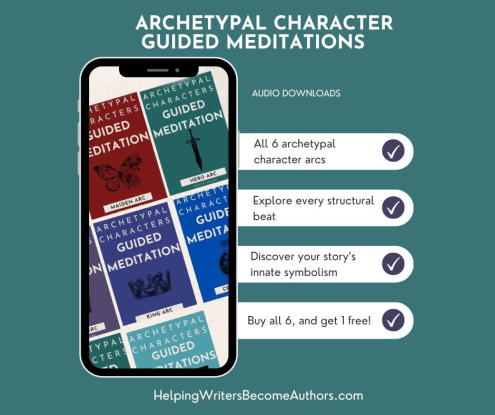

The head, however, remains a worthy ally on this journey. It is not, as it so often thinks, the protagonist. But it is a helpful sidekick. To that end, studying the mythic journeys in literature can be extremely helpful—whether the Hero’s Journey or the five further archetypal journeys I discuss in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs. (Writers can apply these insights practically through my Archetypal Character Arc Worksheets. This worksheet bundle is, in essence, a companion workbook to Writing Archetypal Character Arcs. If you’d like help charting any of the six archetypal character arcs—Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, and Mage—you can check out the worksheets I just released. If you want them all, be sure to check out the discounted bundle.)

Story is not just “about life.” It’s a dream we dream together. It is a map for transformation. If we look into the past, history tells us our storytellers were our seers, our shamans, our wayshowers, our most respected elders.

Now, we are all storytellers. We all bear this great burden to look beyond what everyone else can see and to hone the transformative truths that are meant to initiate not just us but every member of our tribe.

To do that, we must start by remembering what story really is. It is not just entertainment. It is not just escapism. It is not just pleasure. It is not just a source of income.

What is story? I believe the archetypal shape of story is, fundamentally, a truth. Perhaps even the Truth. It is the power to change the world—over and over and over and over again. It is the power to change us. It is the power to bypass our limited egoic perceptions of ourselves, others, and our world and to show us into the wyrdest depths of what it means to be human. It is a dream we dream that also dreams us. It is initiation. It is transformation. It is change. It is myth.

Frequently Asked QuestionsWhat does it mean to say all stories are myth?It means that beneath every plot and genre lies a universal archetypal pattern. From epic fantasies to contemporary romances, all stories echo mythic structures that reflect the psyche’s journey of transformation.Can hyper-realistic stories still be mythic?

Yes. Even the most realistic fiction carries symbolic depth if the writer taps into archetypal storytelling. A courtroom drama or slice-of-life novel can still follow the mythic blueprint of initiation, transformation, and return.Why do archetypes resonate so deeply with readers?

Because archetypes are not stereotypes. They are living psychological forces. When writers use archetypal character arcs, readers feel as though they are watching their own inner conflicts dramatized on the page.How can writers use archetypal character arcs in their stories?

Writers can use arcs like the Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, or Mage as blueprints for character development. These journeys help ensure stories resonate with mythic power and emotional authenticity.In Summary

At their core, all stories are myth. No matter the genre or style, narrative always springs from the archetypal blueprint of the psyche. Story is not simply a mirror of everyday life but a symbolic map of transformation—a dream we dream together. When writers embrace this mythic foundation, they create stories that not only entertain but initiate both writer and reader into deeper self-awareness and lasting change.

Key TakeawaysAll stories are myth. Beneath plot and genre lies the archetypal blueprint of transformation.Story is psyche. Every character and force reflects a facet of the self.Archetypes are alive. They are not tropes but dynamic psychological energies.Hyper-realism needs myth. Realism alone risks losing depth; archetypal foundation restores resonance.Story transforms. Writers and readers alike undergo initiation through narrative.Want More?

Archetypal Character Workbook (Full Bundle of 6)

If you’d like to put these insights into practice, explore my Archetypal Character Arc Worksheets—a series of six fillable, downloadable guides designed to help you chart mythic journeys for your characters. Each worksheet breaks down one of the six archetypal arcs—Maiden, Hero, Queen, King, Crone, and Mage–into structural beat sheets, reflective questions, and story prompts. Whether you’re writing epic fantasy or modern literary fiction, these tools will help you harness archetypal storytelling, deepen your characters, and unlock the mythic power within your narrative. Find the full set (including the discounted bundle) in my Etsy store.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Do you see your own stories as mythic at their core? How do you think recognizing the archetypal foundation of storytelling might change the way you write? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Why All Stories Are Myth—and How They Transform Us appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 30, 2025

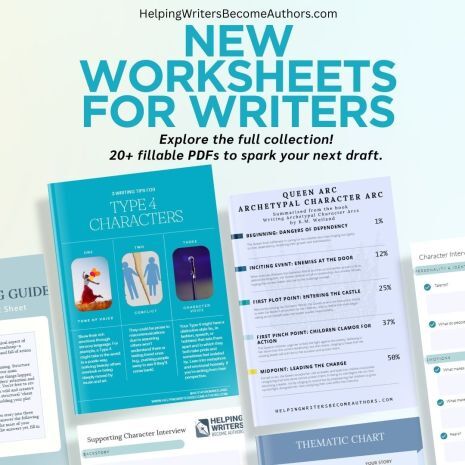

New Worksheets for Writers: Fillable PDFs to Spark Your Story

Sometimes the “quick little projects” are the ones that surprise me the most! Back in the spring, I thought it might be fun to put together a few simple printable writing worksheets—something light and easy, just a side project before the second edition of my Structuring Your Novel Workbook comes out this October.

Of course, you know how that goes.  One idea led to another, and before long my “tiny project” turned into a whole collection of 20+ digital writing resources. And honestly? I had a blast making them. (Seriously. I had to make myself stop!)

One idea led to another, and before long my “tiny project” turned into a whole collection of 20+ digital writing resources. And honestly? I had a blast making them. (Seriously. I had to make myself stop!)

Now, after months of work, I’m excited to share them with you!

Why I Created These Worksheets for WritersWhen I was in grade school, I had a “Write Your Novel” kit that came with worksheets. I can still remember how excited I felt sitting down with those pages—answering questions, filling in blanks, and dreaming up characters and stories. Secretly, that early love of worksheets has never left me. To this day, I still find them ridiculously fun.

Of course, worksheets should never be about ticking off boxes or forcing your story to fit into rigid rules. Writing begins and ends as discovery. But sometimes we all hit blind spots:

An arc that feels flatA theme that won’t come togetherA character who just isn’t coming aliveThis is where worksheets shine. Worksheets are tools to help you spark fresh insight, troubleshoot weak spots, and unlock ideas you didn’t know you had.

My goal was to design practical, easy-to-use tools that:

Give you direct access to the writing techniques I teachSpark new insights into your characters, themes, and plotsOffer flexible, fun ways to brainstorm and outline your storiesWhether you’re working on a novel, screenplay, or even an RPG campaign, these fillable PDF worksheets for writers are designed as creative companions for your storytelling journey.

Browse the entire collection of 20+ worksheets here: [Grab the Worksheets!]

Browse the entire collection of 20+ worksheets here: [Grab the Worksheets!]

If you’re not sure where to start, I’d recommend checking out two special bundles:

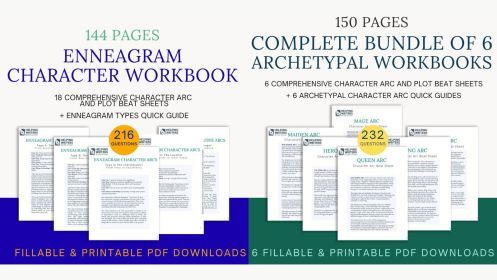

The Archetypal Character Arc Cheat Sheets – Provides quick-glance guides to all six of the major archetypes in the Archetypal Life Cycle. For those of you have been asking, this is really a companion workbook for Writing Archetypal Character Arcs . (And, who knows, if you love the digital worksheets, my next project may be collecting them into a paperback!) The Enneagram Character Arc Cheat Sheets – An 18-worksheet collection for creating powerful arcs (both Positive and Negative) for all nine personality types.Both bundles are steeply discounted so you can grab them at the best value, rather than purchasing each worksheet individually.

After that, here are a few standouts I think you’ll love:

Character Interview Worksheet – 100+ questions to dig deep into your protagonist’s psychology, habits, and quirks. Perfect if you want to truly know your character inside and out. Supporting Character Interview Worksheet – 30 targeted questions for side characters, because your story world comes alive only when all the characters feel real. Character Arc Quick Guide – Beat sheets for all five major arc types (Positive, Flat, Disillusionment, Fall, and Corruption). A handy way to clarify your character’s journey at a glance. Story Structure Beat Sheet – A step-by-step breakdown of the classic seven-beat structure. Use it to tighten pacing or map out missing beats. Theme Worksheet – A 12-page guided exploration of your story’s thematic heart, with resources on character arcs, core elements, and dozens of bonus links.What’s Inside the Worksheets for Writers (The Bonuses!)These aren’t just worksheets—they’re mini writing toolkits. Each one comes with an extensive PDF resource guide packed with links to my most helpful blog posts, podcast episodes, and free tools. That way you can dig deeper into the craft while putting ideas directly into practice.

You’ll also find extras like:

Quick-reference infographics to keep story structure principles at your fingertipsExpanded guidance for flexible worksheet useTips and curated examples to inspire your processSince this is a brand-new launch, your support means so much! You can purchase the worksheets directly from my store, but I’d especially appreciate if you order through my Etsy shop. Every purchase there helps me build credibility and visibility on the platform.

And if you find the worksheets helpful, leaving a quick review on Etsy would be an enormous help in boosting the shop’s ranking!

I made these worksheets with you in mind, and I hope they give you the same spark of excitement I felt while creating them. I can’t wait to see what stories they help you bring to life!

Explore the new worksheets here: [Worksheets Here!]

Explore the new worksheets here: [Worksheets Here!]

The post New Worksheets for Writers: Fillable PDFs to Spark Your Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 25, 2025

What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling? (+ 6 Ways Storytelling Can Find Its Soul Again)

I’ve been feeling it for a while now—that dull, uninspired thud when the credits roll on modern storytelling. More and more, movies in particular leave me feeling unmoved and oddly detached. Bored, really. Once upon a time, I’d walk out of the theater buzzing. I’d carry that story around with me for days, sometimes weeks. I called it a “story high.”

I’ve been feeling it for a while now—that dull, uninspired thud when the credits roll on modern storytelling. More and more, movies in particular leave me feeling unmoved and oddly detached. Bored, really. Once upon a time, I’d walk out of the theater buzzing. I’d carry that story around with me for days, sometimes weeks. I called it a “story high.”

Now? More often than not, I’ve forgotten the movie by the time I reach the parking lot. Actually, most of the time I’m lucky if I remember whatever it was I watched on Netflix last night.

I keep asking myself, “Is it me who has changed?” Because God knows I have. This past decade has transformed almost everything about my life, including my relationship to my own storytelling. So perhaps what I’m experiencing is just “taste drift.” Or has something in the very DNA of our storytelling shifted? Is the drift I’m feeling really that the tilt toward spectacle, franchise maintenance, and safe, surface-level beats has taken all the magic with it?

I’ve been pondering this for a long time now, and I’ve been dancing around this post for a while too—wondering if it’s too shaded by my own subjectivity or, perhaps more tellingly, my own nostalgia and idealism. But you know what? I’m just gonna say it: I miss the way movies used to be.

I’m tired of feeling bored by something that used to delight me to no end. I’m sick of feeling a lack of engagement. I’m exhausted by the magnetism movies fail to hold for me. I used to get butterflies watching movie trailers. Now sometimes I can’t even be bothered—because even if the trailer looks good, will the movie really live up to expectations? Do I really even have expectations any longer???

The bottom line is this: it’s been a long time since more than the occasional and very random new movie (and I’m lumping in all TV and streaming content here) actually made me feel something. I know it’s not just me, because when I go back to the oldies, the difference is palpable. And in my very subjective opinion, it’s time we got back to telling stories the way we used to.

In This Article:What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling?The Impact Movies Have on BooksThe Storytelling Cycle 1970–20256 Qualities Storytelling Is Ready to See AgainWhat’s Happened to Modern Storytelling (Especially Movies)?Well, COVID happened, social media happened, streaming happened, the writers’ and actors’ strikes happened. All those things have massively affected the bottom line of how this very expensive medium is constructed to reach its audience.

But you know what? I don’t even think that’s really it.

When I examine the filmmaking landscape of the last 10–20 years in comparison to the decades that came before, what jumps out at me is the tone.

For a long while now, so much of what we’re offered to consume as storytelling audiences has been overlaid with tones of:

SnarkIronyMeta-commentaryHyper self-awarenessNihilismDeconstructive narrativesNow, admittedly, we’re living in an era of deconstruction, and I don’t necessarily see that as a bad thing. Cycles are made to turn. We need the sour with the sweet. We need the bracing cold against the lazy warmth. Idealism needs a sharp shot of cynicism every now and then. But by that same principle, cynicism eventually needs idealism to take its shot right back. Just as we cannot construct endlessly, neither can we deconstruct ad infinitum.

The Impact Movies Have on BooksBefore I go on, let me say a word about our other important storytelling medium: books. Most specifically in this post, I am referencing the current filmmaking culture in the U.S. However, because of the undeniable influence this visual media has on art of all kinds, we can’t fully separate its struggles or trends from those we find in literature.

In no small part, writing is “monkey see, monkey do.” Even those of us writing novels and short stories are inevitably influenced not just by the books we read, but I would argue perhaps even more so by the visual media we consume. Visual media is not only pervasive, it’s also unparalleled for its memorability. I suppose this is particularly true for visual learners. Speaking for myself, I can say with certainty that the visuals I consume are perhaps the single greatest influence on my storytelling.

More than that, as a comparatively snack-sized consumable, movies and even limited series are, in my opinion, unquestionably the greatest influence upon storytelling structure and techniques for modern writers. In short, what begins in the movies will eventually affect literature.

That said, I don’t feel these concerning trends are as obviously prevalent in literature as in film. Part of the reason for this is that salable literature is a vast landscape in comparison to salable visual media. Mostly, this is because the stakes aren’t as high. Strictly speaking, it costs nothing to create a book in comparison to the staggering millions dropped on visual spectacle. This alone makes books a far more forgiving medium in which to experiment and stretch the bounds of convention or audience expectation.

The book-reading experience can also be much more subjective in its personalization. People are far more likely to be watching the same movies and shows than they are to be reading the same books. Those books we have all read—whether classics or bestsellers—have sometimes been baptized in the fires of public scrutiny a bit more thoroughly than the latest film we’ve “all” seen.

So with all that said, although my own recent experiences with modern novels have been largely more positive than with modern movies, the general downturn in the filmmaking industry certainly crosses over to some extent—making these concerns more about “storytelling” in general than simply “filmmaking.”

The Storytelling Cycle: 1970–2025

Click for larger view.

Although I am undeniably nostalgic for the movie landscape of my teenage and young adult years, the changes I’m picking up on point to more than just that. If we look back just fifty years or so, at the overall storytelling cycle, we can see a clear oscillation:

1970s – Grit & DisillusionmentTone: Cynical realism, moral ambiguity, personal stories.

Examples: The Godfather, Taxi Driver, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Drivers: Post-Vietnam, Watergate, social upheaval. Audiences suspicious of authority. Anti-heroes dominate.

The Godfather (1972), Paramount Pictures.

1980s – Mythic Optimism & Pop EscapismTone: High-concept, archetypal, sincere adventure.

Examples: Star Wars, E.T., Back to the Future, The Princess Bride

Drivers: Blockbuster economics, Reagan-era optimism, VFX advances. The rise of the Hero’s Journey as mainstream glue.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

1990s – Irony & DeconstructionTone: Quirky realism, meta-humor, genre-bending.

Examples: Pulp Fiction, Fight Club, The Matrix, The Truman Show.

Drivers: Post-Cold War uncertainty, Gen X skepticism, indie boom. Themes interrogate reality and authenticity.

The Matrix (1999), Warner Bros.

2000s – Earnest Epic ResurgenceTone: Sweeping, sincere myth for a new millennium.

Examples: The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Gladiator

Drivers: Pre-/post-9/11 yearning for unity, moral clarity. Large-scale adaptations brought back allegory and grand stakes.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), New Line Cinema.

2010s – Meta-Franchise EraTone: Connected universes, quippy self-awareness, formula mastery.

Examples: MCU Phases 1–3, Frozen, Game of Thrones.

Drivers: Social media feedback loops, globalization, IP exploitation. Themes (and conclusive arcs) are often secondary to brand continuity.

The Avengers (2012), Marvel Studios.

2020s – Saturation, Fragmentation, & CautionTone: Brand maintenance, “safe” messaging, heavy serialization, frequent irony to preempt critique.

Examples: MCU Phase 4, Disney’s Star Wars, Rings of Power, The Witcher, Disney’s live-action reboots.

Drivers: Pandemic shifts viewing habits, political polarization, streaming war economics, strikes. Thematic depth appears in pockets (e.g,. Dune), but most mass-market fare is either spectacle-first or message-first.

The Witcher (2019-), Netflix.

6 Qualities Storytelling Is Ready to See AgainSo are we at the end of the current cycle? Are we ready for a resurgence of idealism, hope, wonder, and optimism? Hard to say. Ultimately, I believe these things take as long as they need to take to work their archetypal and energetic perogatives within the overall cycle. But, personally, I think we’re ready. I think it’s time. God knows I’m ready for it as a viewer. More than that, I know this is what I want to write. If I get to have a contribution to the never-ending story of this cycle, then I know this is what I want it to be.

If you’re ready to hop on this train as it’s getting ready to leave the station, here are six qualities I think it’s past time we bring back to mass media.

1. Subtext, Metaphor, and Allegory

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

If I think about one element that is the hallmark of every movie I’ve ever loved, it’s this: it’s subtext. So much of we’re seeing today is either on-the-nose or deliberately subverting its own subtext to create meta references or irony. Story’s richest depths live in subtext. The best stories are about more than just the text. Their subtext offers thematic symbolism with the capability of turning even the simplest story into something deep and true. This is the power of allegory. It is the power of thematic metaphor. Even though all stories offer the potential for this, it actually takes a tremendous amount of courage for a storyteller to resist the urge to simply spell it all out.

When I speak about this, I think about movies like The Legend of Bagger Vance, The Lion King, and Forrest Gump. But even obviously blockbuster stories such as Jurassic Park and The Terminator elevate themselves into timeless and unforgettable experiences through their subtextual expertise. This stands in such blatant contrast to their resurrected franchise sequels—most of which, despite all their bling, are heartless, soulless, and (because you don’t get the first two without this one:) brainless.

Forrest Gump (1994), Paramount Pictures.

2. Mythic Structure and Archetypal Resonance

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

Mythological and archetypal underpinnings lay the foundation for stories of effortless truth. They point to what is most real, and they supply the kind of symbolism that takes audiences deep without even trying. Solid plot structure and character arcs start this off (as they are themselves rooted in myth and archetype), but there is so much more depth we can explore.

It’s true the old stories need to reinvent and resurrect themselves from time to time—or more strictly, culture needs to reinvent its relationship to these stories. We can get so close to them, we begin to think they are “tame lions” and we forget that what they really represent is something terrifyingly beautiful in its raw and primal power.

Our relationship to these structures evolves. But really it is us who evolves more than the structures themselves. I was reminded of this in recently viewing StudioBinder’s excellent retrospective of the Hero’s Journey (in which I was honored to appear):

It is arrogance that lets us think, in all our perky snark and world-weary cynicism, that we write the stories. No, the stories write us. We forget that at our peril, and as storytellers we, above all, safeguard the chthonic depths of our deepest, most terrifying, and most transcendent truths.

The great myths of our age have been movies (either first or perhaps most prevalently): Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter. And they have changed us utterly. For this reason, if no other, I will never be content with even one single story that does not confront me, does not make me feel something, does not transform me.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011), Warner Bros.

3. Emotional Sincerity, Vulnerability, and EarnestnessThis one isn’t always popular. But, honestly, I feel the truth of it deep in my bones: we are missing stories that confront us with emotional sincerity, with vulnerability, and, yes, with earnestness. We’re so jacked on sarcasm and skepticism. Perhaps it began as a tool to transform structures that had seen their day. But now, it’s starting to feel like a defense we’re just hiding behind.

There’s no hiding from hope—the hope that we will be seen, accepted, loved—not for who we are supposed to be, but just as we are in all our messy glory. Think about how hard it is to show up with your heart in your hand.

Although we certainly do see many films these days striving for this (and kudos to them), I can’t help feeling many are still hiding a bit behind their own weariness and tragedy. Sometimes simplicity and innocence and even happiness can feel the most vulnerable of all. I’m thinking of films like Big and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. These are simple—and in some ways very disruptive—comedic romps that reach far beyond themselves through their willingness to show up in the full earnestness of the human capacity for hope and faith.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), Paramount Pictures

4. Moral Clarity (With Nuance)Oh, yes, movies today have a certain moral clarity. At least, they like to tell you exactly what they think (see above about no subtext) and probably exactly what you should think too. Examples abound, from all perspectives. And, frankly, they’re all bad. But then we’ve also got a lot of post-modern confusion going on, and literally a slew of stories whose ambiguity leaves you wondering at the end if there even was a thematic message.

I’ve always liked to say, “Stories are better as questions than as answers.” I still stand behind that. Heavy-handed moralism goes hand in hand with no subtext, and it never works out well. But that doesn’t mean stories can’t (and shouldn’t) have something to say and to say it with all the conviction and nuance they can muster.

Think about Schindler’s List, Amadeus, every John Hughes film ever made, even Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure for crying out loud. These stories know what they are and what they’re trying to say about the world. They say it with assurance, and they offer the package up for us to have our own experiences and make our own judgements.

Schindler’s List (1993), Universal Pictures.

5. Joy and Wonder

Here’s another one that isn’t always praised in our modern film-going culture. But, by God, we need it. Of late, we have been in a time and a place where we have needed to stare down our shadows. But I think it’s time to remember why. Why do we face our shadows? What’s the point? Why is it worth it?

Every story faces its Point of No Return, its Moment of Truth, and its Dark Night of the Soul so it can emerge at the end transformed. The shadow transformed is always light.

I mentioned at the beginning of the article that it’s been a while since I’ve seen a film that really made feel something. If I’ve felt anything at all, it was probably some type of catharsis—grief, anger, shock, disgust. It’s been much longer since a film has taken me to that place of joy and wonder—that revelry just in being alive.

Star Wars did that for me, some of the early MCU movies did that, Secondhand Lions always does that. But these stories don’t have be romps. Joy is always waiting for us at the end of It’s a Wonderful Life, just as wonder waits for us at the end of Princess Mononoke.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

6. Goodheartedness

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

Finally, I am reminded of what Joseph Campbell had to say about the quality of goodheartedness as a necessary quality of anyone who would succeed upon the Hero’s Journey. He spoke of the Irish folk hero Niall, who won his crown through the simplicity of goodheartedness as demonstrated in his kindness to a seeming old crone who was then transformed into the beautiful archetypal force capable of granting him the “Royal Rule.”

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am a friend to the shadows. I believe wholeheartedly in the necessity and courageous importance of facing our shadows—which, in so many ways, is what we are being called upon to do in this moment in time—and reintegrating them into a greater wholeness. All stories reflect humanity’s never-ending struggle with this transformative process. Some parts of the storytelling reflect one aspect; some another.

But even in the midst of our darkest shadow work, may we never forget the crucial piece that is goodheartedness. As storytellers, we bear the great burden of the world’s catharsis—the grief, the anger, our most violent and abhorrent proclivities. But part of that, too—and I would say the most important part—is also the tether to something deeper and truer and better and kinder.

May we write stories like Lord of the Rings and Anne of Green Gables and The Breakfast Club and E.T. and Little Women and Star Wars and Driving Miss Daisy and Harry Potter and Groundhog Day. May we write stories about the heroes we wish we were, the compassion we wish we had, the courage to transform, and the supreme gratitude with which to accept all the glory that is life.

Those are the movies I want to watch again. That’s how you put the whole world on a story high.

In Summary: Why Stories Must Find Their Heart AgainOver the past fifty years, storytelling has swung like a pendulum—from grit and cynicism to myth and wonder, and back again. Right now, we’re in a season of fragmentation, irony, and surface-level spectacle. But history suggests the cycle always turns. What’s missing today (and what audiences are aching for) is a return to sincerity, subtext, allegory, and stories that dare to make us feel something real.

Key TakeawaysModern movies often feel hollow because spectacle has replaced subtext.Storytelling moves in cultural cycles: grit → myth → irony → sincerity.We’re likely on the cusp of another turn toward earnest, mythic storytelling.Writers and filmmakers can be part of that shift by embracing sincerity, allegory, and goodheartedness.Want More?If this resonates, check out my Shadow Archetypes email course. Over eight weeks, we’ll explore the passive and aggressive shadow polarities of the six main archetypes in the Archetypal Life Cycle. It’s a deep dive into how the darker sides of our characters (and ourselves) shape narrative truth. You can sign up here.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think happened to modern storytelling? Do you feel the same hollow note I’ve described, or do you think the magic is still out there if we just know where to look? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling? (+ 6 Ways Storytelling Can Find Its Soul Again) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 18, 2025

Writing Better Character Conflicts With the 5 Conflict Management Styles

Note From KMW: Before we get started today, I just wanted to let you know that this weekend, I’m excited to be sharing a presentation at the WorldShift: The Speculative Fiction Writers’ Summit 2025. This is a free, 4-day online event packed with workshops on character, worldbuilding, plotting, publishing, and more from 30+ writing experts. Whether you write speculative fiction or not, you’ll walk away with tools you can use in any story. You can grab your free ticket here: Join the Summit.

Note From KMW: Before we get started today, I just wanted to let you know that this weekend, I’m excited to be sharing a presentation at the WorldShift: The Speculative Fiction Writers’ Summit 2025. This is a free, 4-day online event packed with workshops on character, worldbuilding, plotting, publishing, and more from 30+ writing experts. Whether you write speculative fiction or not, you’ll walk away with tools you can use in any story. You can grab your free ticket here: Join the Summit.

***

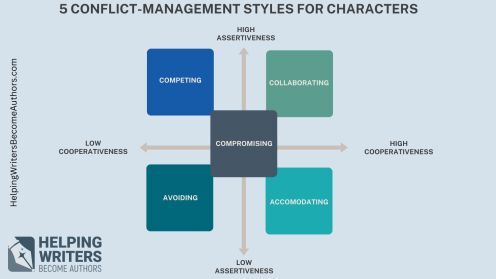

In fiction, every clash between characters comes down to a conflict management style. This is true whether you’re writing a heated argument or a quiet standoff. In real life, psychologists group these into five main approaches: competing, collaborating, compromising, accommodating, and avoiding. Understanding how each works can help you write richer, more realistic character conflicts.

It is a common axiom in the writing world that conflict drives story. Although the simplicity of this advice is necessarily limited, what it means is that plot is created from a series catalysts that cause characters to respond. Basically: cause and effect.

This is what then creates the chain of story events (aka, scenes) that engenders the larger story. At its simplest, story conflict is nothing more or less than some kind of obstacle interfering with a character’s forward progression. That said, the word “conflict” itself does tend to most readily connote interpersonal conflict—whether in the form of a fistfight or a passive-aggressive argument. Indeed, most people find this aspect of conflict to be the most obviously entertaining and useful for plot, since it tends to inherently combine all three of a story’s major engines: plot, theme, and character.

This means that much of what writers need to know about conflict in general comes down to character conflicts. The more nuanced your characterizations, the more interesting the conflict will be and the more realistic and compelling your characters will be.

So how do you create nuanced character conflict?

One way is to study and understand conflict management styles. If you can figure out which conflict management styles best fit your characters, you not only have the opportunity to create instantaneously complex relationship dynamics (since every character’s approach to conflict will be different), but also conflict that naturally arises from the management styles themselves (e.g., characters with opposing styles can sometimes spark conflict just because they clash with each other’s approaches).

In This Article:Take the Test: What Are the 5 Conflict Management Styles?Using the 5 Conflict Management Styles to Build Character ConflictThe Competing Style: High-Stakes ShowdownsThe Collaborating Style: Win-Win SolutionsThe Compromising Style: Meeting in the MiddleThe Accommodating Style: The Peacemaker’s PathThe Avoiding Style: Delaying the BattleTips for Mixing Conflict Styles in Your StoryTake the Test: What Are the 5 Conflict Management Styles?The idea of five distinct conflict management styles comes from the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI), developed in the early 1970s by psychologists Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann. Originally designed for workplace and organizational settings, the model maps how people handle conflict along two dimensions: how a person pursues one’s own goals (i.e., a spectrum of unassertiveness and assertiveness) and how one considers others’ goals (i.e., a spectrum of uncooperativeness to cooperativeness). From there, they used these two axes to map five core approaches to conflict: competing, collaborating, compromising, accommodating, and avoiding.

To discover which style best fits your characters (and yourself!), you can purchase the official test here. Below is a short version that can get you started by giving you the general idea:

Character Conflict Style QuizDiscover how your characters naturally handle disagreements, tension, and power struggles. Start by choosing a single character you want to assess. For each statement below, imagine how this character would respond in a variety of situations (e.g., with friends, rivals, strangers, etc.).

Rate each statement on a scale of 1–5:

1 = Strongly Disagree

2 = Disagree

3 = Neutral / Sometimes True

4 = Agree

5 = Strongly Agree

At the end, follow the scoring guide to discover your character’s dominant conflict style(s).

The StatementsMy character pushes hard for his/her own way, even if it risks upsetting others.My character seeks solutions that work for everyone involved in the disagreement.My character will give up part of what he/she wants if it helps resolve the conflict.My character often lets others have their way to keep the peace.My character avoids bringing up issues unless there’s no other choice.My character enjoys finding creative solutions in which everyone feels satisfied.My character is willing to settle halfway if it ends the argument quickly.My character puts the other person’s needs first when harmony matters most.My character changes the subject or withdraws to avoid escalation.My character insists on his/her own position, believing he/she’s right.ScoringAdd the scores for each style category:

Competing = Q1 + Q10Collaborating = Q2 + Q6Compromising = Q3 + Q7Accommodating = Q4 + Q8Avoiding = Q5 + Q9Highest Score → This is your character’s dominant style in conflict.

Close Second(s) → These could be secondary style(s) your character may use in certain situations.

Lowest Score(s) → These are the styles your character is least likely to use.

Use the dominant style to shape your characters’ dialogue, body language, and choices in tense scenes. From there, you can play with your story’s conflict by putting your characters in situations that force them into their weakest styles. Not only does this usually create more conflict, but it’s great for growth arcs and plot twists. Also, look for ways to combine different styles in ensemble casts to create natural friction between characters.

Understanding conflict management styles for your characters can provide a solid foundation that influences many aspects of your story. This lays the groundwork for realistic personalities, while also contributing to how you manage each scene’s tension, pacing, and tone. It will influence how character relationships play out, and—since this is usually the heart of any story—from there it can end up creating the plot all by itself.

If you realize any one character lacks a strong conflict style and/or many of your characters share the same style, you can easily troubleshoot for a stronger narrative by mixing things up or strengthening the accuracy and consistency of how a particular conflict style is showing up in your story.

Using the 5 Styles Conflict Management Styles to Build Character ConflictLet’s take a deeper look at each of the five styles and how each one might show up in your fiction.

5 Conflict Management Styles for Writers Graph (click for larger view).

1. The Competing Style: High-Stakes ShowdownsCharacters with a Competing style go all in to get what they want. They score high in both assertiveness and uncooperativeness, which means they tend to prioritize victory over relationships. This can be a great way to raise the stakes, since it creates scenarios with clear winners and losers.

Although these characters often come across as selfish, they can also be excellent leaders since they are ultimately all about efficiency. Their focus is entirely on getting results, which can actually be on behalf of someone else (i.e., protecting or providing for the group) even if relationships are often not factors in the decision making.

For Example:

Miranda Priestly in The Devil Wears Prada relentlessly pushes her own agendas, regardless of how it impacts others. When she demands Andrea obtain an unpublished Harry Potter manuscript for her twins, Miranda exerts total control, making it clear her needs come before anyone else’s.

The Devil Wears Prada (2006), 20th Century Fox

Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick obsessively pursues his own goal (killing the whale), even at the cost of his crew’s safety. He rallies the crew to join his hunt for Moby-Dick, overriding the ship’s original mission and dismissing the first mate Starbuck’s concerns.

When two characters team up to find a solution that works for everyone, they’re Collaborating. Unlike the Competing style, the Collaborating style can often serve to strengthen connections even while highlighting differences. Like Competitors, Collaborators score high in assertiveness. They’re there to get the job done, but because they also score high in cooperativeness, they wish to do so in a way that doesn’t clearly define themselves as winners and everyone else as losers.

These characters make great leaders, although usually more heart-based than the head-based Competitors. Sometimes their downfall can be trying to make situations work for everyone when that isn’t possible or desirable (which can ironically cause everyone to “lose”).

For Example:

As she becomes a leader, Moana works to find solutions that honor her people’s traditions while also solving their urgent needs. When she realizes the antagonist is actually the goddess Te Fiti, Moana does not seek to defeat her, but rather restores her heart, resolving the conflict in a way that benefits everyone.

Moana (2016), Walt Disney Pictures.

Atticus Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird strives to seek truth and fairness by balancing empathy with justice and involving others in the moral conversation. During his courtroom defense of Tom Robinson, he appeals to the jury’s conscience and shared values in an attempt to gain a resolution that serves both justice and his community’s moral integrity.

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), Universal Pictures.

3. The Compromising Style: Meeting in the MiddleThis style desires both sides to give a little and meet in the middle. Compromisers tend to create a partial resolution that still leaves some tension in play. Compromisers ride the middle of both axes—assertiveness and cooperation—landing somewhere betwixt and between. Because they lack as much assertiveness as Competitors and Collaborators, they tend to fill leadership roles only reluctantly and in the absence of someone more decisive. This isn’t necessarily because the more decisive types are better leaders, but because those types can sometimes fill the role faster, while the Compromising type is still examining all the options.

The Compromising style can often lend itself to indecision. Because their greatest desire is for everyone to be happy, they can get stuck in pursuit of an impossible ideal. They can be frustrating to both assertive types, but offer valuable and necessary perspectives.

For Example:

Marty McFly in Back to the Future consistently seeks middle-ground solutions to avoid outright confrontation, like persuading George to stand up to Biff so he doesn’t have to directly fight Biff himself, or finding a way to get the time machine running without demanding perfection from Doc.

Back to the Future (1985), Universal Pictures.

Katniss Everdeen in The Hunger Games often negotiates partial agreements with allies (like Peeta or Haymitch) to survive, while still holding to her values. Although she will fight if pushed (indicating a secondary conflict style), she generally prefers to find workaround solutions.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

4. The Accommodating Style: Seeking PeaceSometimes a character will give in to keep the peace, a choice that can alternatively reveal loyalty, fear, or quiet acts of self-sacrifice. This conflict style scores low in assertiveness and high in cooperativeness. Although this style often lends itself to characters who can get run over by more assertive types, it also represents the most empathetic of the five. This is usually a person who is highly tuned in to others.

However, their conflict aversion can make it difficult for them to get what they want or to pursue (or sometimes even acknowledge) their own desires. If they don’t have a strong secondary style to help them out, they can (ironically) struggle to create enough conflict to drive the plot.

For Example:

Samwise Gamgee in The Lord of the Rings shows Accommodating tendencies in his dedication to putting Frodo’s needs and safety above his own desires, even when it’s hard, such as on Mt. Doom when he gives Frodo the last of their water instead of taking it himself, prioritizing Frodo’s needs over his own survival. However, Sam also shows a strong secondary Competitive style, especially when confronting Gollum.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), New Line Cinema.

Beth March in Little Women consistently yields to her sisters’ wishes in order to maintain family harmony, even at personal cost. For instance, when Meg is invited to a party, Beth encourages her to go even though it means Beth will left be alone.

Little Women (1994), Columbia Pictures.

5. The Avoiding Style: Delaying the BattleFinally, instead of facing the issue, a character might dodge the conflict entirely. Although this can totally deflate a scene’s conflict, it can also lend itself to subtextual passive-aggression as the tension builds in the silence and unresolved emotions linger. Notably, although this type scores low in assertiveness, it scores high in uncooperativeness.

This style often lends itself to loner characters who prefer to go their own way rather than engage with others. It is separate from the Accommodating style in that it is more concerned with protecting itself than placating others. The true Avoidant style will also do almost anything to avoid conflict. It would rather slip away (either physically or by disassociation) than bond or fight in order to end the dispute.

For Example:

Christopher McCandless in Into the Wild consistently sidesteps the deep conflict of his strained family relationships, instead physically removing himself by leaving home and embarking on a solo journey into the wilderness. His avoidance defines not just isolated moments, but his entire approach to life’s tensions.

Into the Wild (2007), Paramount Vantage

Bruce Banner in The Avengers keeps a low profile in Calcutta, tending to patients and dodging any situation that might trigger his transformation. His alter-ego, the Hulk, of course, displays the opposite conflict style of Competitor.

The Incredibles (2004), Walt Disney Pictures.

Tips for Mixing Conflict Styles in Your StoryAlthough most characters will demonstrate a primary conflict style, this doesn’t mean they can’t utilize secondary tactics as well. Usually, secondary tactics will represent a less well-developed (and therefore less “mature”) approach that kicks in when the primary style proves counter-productive.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

You can use conflict styles as a central fulcrum in creating a character arc. For example, a character who relies exclusively on a Competing style might have to learn how to become less aggressive and more Cooperative. Likewise, as in Into the Wild, your story could focus on the dangers of taking any one conflict style to a tragic extreme.

One of the single best ways to utilize conflict styles in your story is to focus on the interplay between how the styles show up in different characters.

For Example:

Two Accomodating characters will probably cancel each other out, creating a scene that lacks conflict (and probably nobody getting what they want either).Two Competitive characters will be entertaining, but unless one of them arcs otherwise, their story will always end with clear winners and losers.Competitive and Collaborative leaders can create interesting stories that start with sparks and end with mutual growth.Compromising characters can often struggle in confronting other types, but offer both balanced perspectives and room for growth.With deep roots in psychology, conflict management styles make for powerful storytelling tools. By giving each character a clear, consistent approach to conflict, you can create authentic tension, natural relationship dynamics, and plot turns that feel inevitable. You may want to see your characters locking horns in a showdown or finding creative win-win solutions or slipping quietly out the back door. Whatever the case, the way they handle conflict will shape everything from pacing to theme. Mastering these five styles can help you write stories that feel more real, more layered, and far more compelling.

In SummaryThe five conflict management styles—Competing, Collaborating, Compromising, Accommodating, and Avoiding—offer writers a structured way to design believable interpersonal conflict. Each style is defined by how characters balance assertiveness (pursuing their own goals) and cooperativeness (considering others’ goals). Assigning conflict styles to characters adds depth, realism, and tension to your scenes and relationships. Going further, to mix different styles in your cast can then naturally generate friction and plot momentum. You can even shift a character’s style over time to create satisfying character arcs.

Key TakeawaysConflict drives story. Knowing your characters’ conflict styles makes that conflict richer and more organic.Different styles = different sparks. Pairing contrasting styles creates built-in tension, while matching styles can either cancel conflict or amplify it.Extreme reliance on one style can be a flaw that drives an arc or downfall.Use the Character Conflict Style Quiz to quickly identify how your characters approach disagreements.Incorporating real-world psychology models into fiction can boost authenticity and reader engagement.Want More?

Creating Character Arcs Workbook

If you’d like to take your character development even further, check out my Creating Character Arcs Workbook. Packed with guided exercises, prompts, and structure templates, it will help you chart your characters’ journeys from start to finish. It covers Positive Change Arcs, Flat Arcs, and Negative Change Arcs. Learn how to weave plot and character together seamlessly so every scene feels purposeful and emotionally resonant. It’s available in e-book and paperback.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinion! Which of your characters has the most clearly defined conflict management style, and how has it shaped relationships or the plot? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Writing Better Character Conflicts With the 5 Conflict Management Styles appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 11, 2025

How to Start Dictating Fiction (Even If You’ve Tried and Failed Before)

From KMW: I’ve always loved writing by hand. There’s something about the feel of pen on paper that just makes the creative process click for me, especially when outlining and brainstorming. However, between the wrist pain, bad posture, and the fact that I can’t read my own handwriting half the time, I’ll admit there are certain downsides—just as there are to typing. I’ve dabbled with dictation off and on over the years, but I always hit the same wall: it just didn’t feel like “real” writing. If I wasn’t typing or scribbling, was I actually creating?

From KMW: I’ve always loved writing by hand. There’s something about the feel of pen on paper that just makes the creative process click for me, especially when outlining and brainstorming. However, between the wrist pain, bad posture, and the fact that I can’t read my own handwriting half the time, I’ll admit there are certain downsides—just as there are to typing. I’ve dabbled with dictation off and on over the years, but I always hit the same wall: it just didn’t feel like “real” writing. If I wasn’t typing or scribbling, was I actually creating?

But as I read Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer’s guest post this week, I had to rethink that a bit. She breaks down some of the myths and mental roadblocks around dictating fiction in such a grounded, compassionate way that it made me realize something kind of obvious (but also kind of profound): storytelling was originally oral. We had voices and listeners long before we had keyboards or pens!

So if you’ve ever felt curious about dictation but haven’t been sure where to start (or, like me, have gotten frustrated after trying it), I think you’ll find Sarah’s approach refreshing. She’s been where you are, and she’s mapped out a path forward that’s both practical and encouraging. Enjoy!

***

Have you ever read about an author who dictates 5,000+ words while taking a walk and thought to yourself, “If dictation is so amazing, why isn’t everyone doing it?”

Maybe you’ve tried dictation. You opened a voice app, started talking, and… froze. It felt awkward. Disjointed. The transcription was a mess.

After working with hundreds of authors making the transition from typing to speaking their words of fiction, I know this story well. It was my story when I first tried dictation. And failed. Again and again.

Dictation is one of the most misunderstood tools for authors, yet one with potential for powerful transformation in your author life.

In This Article:4 Myths About Using Dictation to Write FictionHow to Get Started With Dictating (Even if You’ve Failed Before)The Next Step: Making Dictation Effortless4 Myths About Using Dictation to Write FictionAs someone who has dictated 14 books and trained hundreds of authors in how to dictate fiction, I want to say this: dictation isn’t a magic shortcut that will solve all your writing challenges. But it tackles a great many of them.

And dictation can absolutely be learned, just as you learned how to handwrite and type. I want you to get there without getting overwhelmed.

Let’s start by eliminating common myths around dictating fiction.

Myth #1: Dictation = Talking Fast = Writing FastWhen you think about dictation, speed is probably the first thing that comes to mind. Speed is what drew me and countless authors to give it a shot.

Dictation can help you draft faster. I doubled my writing speed from 1,500 words of fiction per hour to 3,000 words, and with less strain on my body.

But when you only see dictation as a way to supercharge your productivity, you might experience frustration and even disappointment before you’ve trained yourself to do it well.

Dictation isn’t a race to speak as fast as you can. I talk slower when dictating fiction than when I’m having a conversation.

If you find yourself slowing down to dictate, that’s normal. In fact, I encourage it. Take your time. Pause. Breathe. When you’re ready, tackle the next sentence.

Speed will come with practice.

But dictation isn’t just writing faster. There are health benefits since dictation frees you from your desk.

It can also help you break through mental blocks around your plot, develop better dialogue, and get words squeezed into the little spaces of life: doing the dishes, sitting in the car pool line, or walking the dog.

While dictation can lead to faster drafts, I’ve seen these other benefits outweigh speed.

Myth #2: “I Tried Dictation, It’s Just Not for Me.”This is the one I hear most. It was the myth that held me back for years.

Maybe you tried dictation while walking. Or you spoke your story into your phone one morning and felt completely disconnected from the words. Maybe the transcription came back such a mess, you decided it wasn’t worth the hassle.

I hear you. My first shot at dictation, I thought I was on to something. In 2013, I posted on social media how I dictated a few words of fiction, and how it could be epic. And it was.

An epic failure.

I couldn’t get past the mental and technical hurdles of speaking my words instead of typing.

I went through it all: staring at a blank screen with an equally blank imagination. I stumbled over words, dreaded hearing my voice, and had no idea how to clean up my transcriptions.

I didn’t know what I was doing and made a mess of everything.

Dictation just wasn’t for me.

But then I realized something: I needed to train myself to dictate just like I trained myself how to type. You need to dig new neural trenches in your brain to allow the words to flow through your mouth as naturally as your fingertips.

I came back to dictation in 2020. I released the pressure on my brain to dictate fiction. I started practicing by dictating my morning pages and text messages. Then I experimented with apps and methods until I found what worked for me. I stopped expecting it to immediately “feel right.”

Slowly, it started to work. I found my rhythm. I dictated a full (backstory) scene. Then a full chapter. Then a full novel.

Now, dictation is how I write my first drafts. I write faster and enjoy the process of creating fiction even more than when I typed (much more enjoyment through the “muddy middle” of a first draft where I always got stuck when typing).

Myth #3: You Need Fancy Software or EquipmentBack in the day, your only option to dictate fiction was to hire a private secretary or transcriptionist at hundreds or thousands of dollars per novel. Then it became more affordable with the entrance of Dragon Dictation at under $1,000 for unlimited novels.

I’ve never used Dragon to dictate my novels.

Nowadays, you don’t need expensive software to start. You likely already own what you need to dictate fiction at little to no cost:

A smartphone or computerA free transcription service (the one built into your device works just fine)A quiet space (optional, but helpful)Yes, there are other tools and methods out there (I dictate on my phone directly into my Scrivener iOS app. You can get a free mini-course on my methods here.). But when you’re starting out, I found it’s best to keep it simple. In fact, adding too much tech too soon is one of the fastest ways to get overwhelmed.

Start easy. Get comfortable with the feel of speaking words and having them transcribed. Once that’s second nature, you can develop methods and experiment with tools that fit your process and lifestyle.

Myth #4: Dictated Drafts Are Too Messy to Be Worth ItYes, dictated drafts are messy.

But so are most first drafts.

I’ve developed a cleanup process that’s fast and gets my dictated drafts reading as well as a typed first draft. It’s still a mess to deal with in the editing phase, but I’m starting with the same type of messy first draft.

Dictation helps you let go of perfectionism and get your messy first draft on the page so you can edit it later. When you type, it’s easy to backspace, rewrite, and tweak every sentence endlessly. Dictation makes that harder, which helps you get to “the end.”

Instead of editing as you go, dictation invites you to get the story out of your head and onto the page. The refinement comes later, during revision.

How to Get Started with Dictating (Even If You’ve Failed Before)After working with hundreds of authors on making the transition from typing to speaking their words, I’ve found three keys that make all the difference:

1. Embrace the DiscomfortDictating fiction will feel awkward. As the sign over my desk says, “I know I’m in my own little world, but they all know me here.”

To speak “their” worlds out loud feels more vulnerable than typing. At least at first.

But remember, discomfort is a sign of growth. It’s a sign of learning. Lean into that feeling, knowing that’s what will get you to the other side in developing the skill of dictating your fiction.

Give yourself permission to be a beginner.

2. Start With Low-Stakes ScenesInstead of launching into dictation in the middle of your current work-in-progress (WIP), remove the pressure from your brain by picking a scene you can write with a familiar character’s backstory. Have fun with it. Let your imagination run free while you speak your words.

It may come out looking more like a scene outline than an actual scene. That’s okay. You are training yourself to speak fiction instead of typing it.

Everything is progress.

3. Set a TimerI have a power habit I call 5 Minutes of Fiction. This helped me get back into writing after a recovery sabbatical I took in recent years.

As I’ve taught this habit, writers have shared with me how it’s helping them practice dictation. The main idea is that you dictate for just 5 minutes every day.

It can be on a “throwaway” story, backstory, flash fiction, or your current WIP. Set a timer or check the clock before you start, and only go for 5 minutes. Don’t judge what you wrote. Just move on with your day (which may be typing the rest of the words for your writing session).

I created the 5-Minute Fictation Club for authors to tackle this habit together.

Club for authors to tackle this habit together.

Once you start, you’ll be surprised at how confident you begin to feel each time you do your 5 minutes.

The Next Step: Making Dictation EffortlessI’m a big fan of finding ways to make things easier and more fun. Effortless.

That’s part of what dictation has done for my author life, along with a host of other benefits. It’s why I’ve developed ways to make learning dictation as effortless for you as possible.

If you’ve tried dictation and failed, or if you’ve wanted to try but felt overwhelmed, I’ve created something for you: a free Dictation Quick Start Guide for Fiction Authors designed to help you take your first steps in dictating your fiction.

As one author told me,

Dictation can free you.

Let it free you to live your best creative lifestyle.

In SummaryDictating fiction isn’t a magic fix, but it is a learnable skill that can transform your writing process by boosting your word count and freeing you from your desk. If you’ve tried dictation and felt awkward or overwhelmed, you’re not alone and you’re not doomed to fail. With the right expectations, a simplified approach, and a bit of patience, you can develop your own voice (literally) and discover a writing method that works with your lifestyle instead of against it.

Key TakeawaysDictation isn’t just about speed. It can improve your health, productivity, and even creativity.Initial discomfort is normal. Like any writing skill, dictation requires practice to feel natural.You don’t need fancy tools. A smartphone and basic transcription software are enough to start.Messy drafts are part of the process. Dictation helps you overcome perfectionism and get words on the page.Ease into it. Start with low-stakes scenes (like backstory) and short 5-minute sessions to build confidence.Training your brain to speak fiction is possible. Dictation is a skill anyone can learn with the right approach.Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Have you ever trying dictating your fiction? Does it sound helpful? Tell us in the comments!The post How to Start Dictating Fiction (Even If You’ve Tried and Failed Before) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

August 4, 2025

The 5 Types of Scene Endings Every Writer Must Master

There’s nothing quite like a scene that ends with a bang—or at least a purposeful beat that pulls readers deeper into the story. A well-crafted scene ending doesn’t just wrap things up, it launches momentum into the next scene, tightens your pacing, and deepens the emotional arc. Your scene might close in any number of ways, everything from a victory to a setback or a plot twist to a moment of quiet revelation. Whatever the case, scene endings create the impression that will (hopefully) carry readers into what comes next. Really, your writer’s toolbox doesn’t contain many tools more powerful than scene endings, yet they can be easily overlooked when it comes to tightening tension or strengthening overall story structure.

There’s nothing quite like a scene that ends with a bang—or at least a purposeful beat that pulls readers deeper into the story. A well-crafted scene ending doesn’t just wrap things up, it launches momentum into the next scene, tightens your pacing, and deepens the emotional arc. Your scene might close in any number of ways, everything from a victory to a setback or a plot twist to a moment of quiet revelation. Whatever the case, scene endings create the impression that will (hopefully) carry readers into what comes next. Really, your writer’s toolbox doesn’t contain many tools more powerful than scene endings, yet they can be easily overlooked when it comes to tightening tension or strengthening overall story structure.

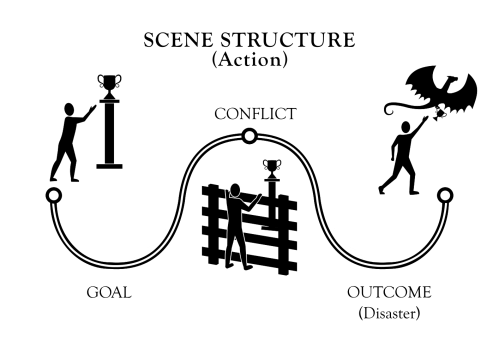

Classic scene structure breaks scenes into two broad halves: scene (action) and sequel (reaction). The scene half further breaks down into three primary pieces:

1. Goal (drives the action and intent of the scene as the character moves toward something).

2. Conflict (creates drama and complications by inserting obstacles that divert the smooth course of the character’s progression).

3. Outcome (shows the conclusion of the character’s efforts and reveals new complications leading to the next scene’s goal).