What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling? (+ 6 Ways Storytelling Can Find Its Soul Again)

I’ve been feeling it for a while now—that dull, uninspired thud when the credits roll on modern storytelling. More and more, movies in particular leave me feeling unmoved and oddly detached. Bored, really. Once upon a time, I’d walk out of the theater buzzing. I’d carry that story around with me for days, sometimes weeks. I called it a “story high.”

I’ve been feeling it for a while now—that dull, uninspired thud when the credits roll on modern storytelling. More and more, movies in particular leave me feeling unmoved and oddly detached. Bored, really. Once upon a time, I’d walk out of the theater buzzing. I’d carry that story around with me for days, sometimes weeks. I called it a “story high.”

Now? More often than not, I’ve forgotten the movie by the time I reach the parking lot. Actually, most of the time I’m lucky if I remember whatever it was I watched on Netflix last night.

I keep asking myself, “Is it me who has changed?” Because God knows I have. This past decade has transformed almost everything about my life, including my relationship to my own storytelling. So perhaps what I’m experiencing is just “taste drift.” Or has something in the very DNA of our storytelling shifted? Is the drift I’m feeling really that the tilt toward spectacle, franchise maintenance, and safe, surface-level beats has taken all the magic with it?

I’ve been pondering this for a long time now, and I’ve been dancing around this post for a while too—wondering if it’s too shaded by my own subjectivity or, perhaps more tellingly, my own nostalgia and idealism. But you know what? I’m just gonna say it: I miss the way movies used to be.

I’m tired of feeling bored by something that used to delight me to no end. I’m sick of feeling a lack of engagement. I’m exhausted by the magnetism movies fail to hold for me. I used to get butterflies watching movie trailers. Now sometimes I can’t even be bothered—because even if the trailer looks good, will the movie really live up to expectations? Do I really even have expectations any longer???

The bottom line is this: it’s been a long time since more than the occasional and very random new movie (and I’m lumping in all TV and streaming content here) actually made me feel something. I know it’s not just me, because when I go back to the oldies, the difference is palpable. And in my very subjective opinion, it’s time we got back to telling stories the way we used to.

In This Article:What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling?The Impact Movies Have on BooksThe Storytelling Cycle 1970–20256 Qualities Storytelling Is Ready to See AgainWhat’s Happened to Modern Storytelling (Especially Movies)?Well, COVID happened, social media happened, streaming happened, the writers’ and actors’ strikes happened. All those things have massively affected the bottom line of how this very expensive medium is constructed to reach its audience.

But you know what? I don’t even think that’s really it.

When I examine the filmmaking landscape of the last 10–20 years in comparison to the decades that came before, what jumps out at me is the tone.

For a long while now, so much of what we’re offered to consume as storytelling audiences has been overlaid with tones of:

SnarkIronyMeta-commentaryHyper self-awarenessNihilismDeconstructive narrativesNow, admittedly, we’re living in an era of deconstruction, and I don’t necessarily see that as a bad thing. Cycles are made to turn. We need the sour with the sweet. We need the bracing cold against the lazy warmth. Idealism needs a sharp shot of cynicism every now and then. But by that same principle, cynicism eventually needs idealism to take its shot right back. Just as we cannot construct endlessly, neither can we deconstruct ad infinitum.

The Impact Movies Have on BooksBefore I go on, let me say a word about our other important storytelling medium: books. Most specifically in this post, I am referencing the current filmmaking culture in the U.S. However, because of the undeniable influence this visual media has on art of all kinds, we can’t fully separate its struggles or trends from those we find in literature.

In no small part, writing is “monkey see, monkey do.” Even those of us writing novels and short stories are inevitably influenced not just by the books we read, but I would argue perhaps even more so by the visual media we consume. Visual media is not only pervasive, it’s also unparalleled for its memorability. I suppose this is particularly true for visual learners. Speaking for myself, I can say with certainty that the visuals I consume are perhaps the single greatest influence on my storytelling.

More than that, as a comparatively snack-sized consumable, movies and even limited series are, in my opinion, unquestionably the greatest influence upon storytelling structure and techniques for modern writers. In short, what begins in the movies will eventually affect literature.

That said, I don’t feel these concerning trends are as obviously prevalent in literature as in film. Part of the reason for this is that salable literature is a vast landscape in comparison to salable visual media. Mostly, this is because the stakes aren’t as high. Strictly speaking, it costs nothing to create a book in comparison to the staggering millions dropped on visual spectacle. This alone makes books a far more forgiving medium in which to experiment and stretch the bounds of convention or audience expectation.

The book-reading experience can also be much more subjective in its personalization. People are far more likely to be watching the same movies and shows than they are to be reading the same books. Those books we have all read—whether classics or bestsellers—have sometimes been baptized in the fires of public scrutiny a bit more thoroughly than the latest film we’ve “all” seen.

So with all that said, although my own recent experiences with modern novels have been largely more positive than with modern movies, the general downturn in the filmmaking industry certainly crosses over to some extent—making these concerns more about “storytelling” in general than simply “filmmaking.”

The Storytelling Cycle: 1970–2025

Click for larger view.

Although I am undeniably nostalgic for the movie landscape of my teenage and young adult years, the changes I’m picking up on point to more than just that. If we look back just fifty years or so, at the overall storytelling cycle, we can see a clear oscillation:

1970s – Grit & DisillusionmentTone: Cynical realism, moral ambiguity, personal stories.

Examples: The Godfather, Taxi Driver, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest

Drivers: Post-Vietnam, Watergate, social upheaval. Audiences suspicious of authority. Anti-heroes dominate.

The Godfather (1972), Paramount Pictures.

1980s – Mythic Optimism & Pop EscapismTone: High-concept, archetypal, sincere adventure.

Examples: Star Wars, E.T., Back to the Future, The Princess Bride

Drivers: Blockbuster economics, Reagan-era optimism, VFX advances. The rise of the Hero’s Journey as mainstream glue.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

1990s – Irony & DeconstructionTone: Quirky realism, meta-humor, genre-bending.

Examples: Pulp Fiction, Fight Club, The Matrix, The Truman Show.

Drivers: Post-Cold War uncertainty, Gen X skepticism, indie boom. Themes interrogate reality and authenticity.

The Matrix (1999), Warner Bros.

2000s – Earnest Epic ResurgenceTone: Sweeping, sincere myth for a new millennium.

Examples: The Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter, Gladiator

Drivers: Pre-/post-9/11 yearning for unity, moral clarity. Large-scale adaptations brought back allegory and grand stakes.

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), New Line Cinema.

2010s – Meta-Franchise EraTone: Connected universes, quippy self-awareness, formula mastery.

Examples: MCU Phases 1–3, Frozen, Game of Thrones.

Drivers: Social media feedback loops, globalization, IP exploitation. Themes (and conclusive arcs) are often secondary to brand continuity.

The Avengers (2012), Marvel Studios.

2020s – Saturation, Fragmentation, & CautionTone: Brand maintenance, “safe” messaging, heavy serialization, frequent irony to preempt critique.

Examples: MCU Phase 4, Disney’s Star Wars, Rings of Power, The Witcher, Disney’s live-action reboots.

Drivers: Pandemic shifts viewing habits, political polarization, streaming war economics, strikes. Thematic depth appears in pockets (e.g,. Dune), but most mass-market fare is either spectacle-first or message-first.

The Witcher (2019-), Netflix.

6 Qualities Storytelling Is Ready to See AgainSo are we at the end of the current cycle? Are we ready for a resurgence of idealism, hope, wonder, and optimism? Hard to say. Ultimately, I believe these things take as long as they need to take to work their archetypal and energetic perogatives within the overall cycle. But, personally, I think we’re ready. I think it’s time. God knows I’m ready for it as a viewer. More than that, I know this is what I want to write. If I get to have a contribution to the never-ending story of this cycle, then I know this is what I want it to be.

If you’re ready to hop on this train as it’s getting ready to leave the station, here are six qualities I think it’s past time we bring back to mass media.

1. Subtext, Metaphor, and Allegory

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

If I think about one element that is the hallmark of every movie I’ve ever loved, it’s this: it’s subtext. So much of we’re seeing today is either on-the-nose or deliberately subverting its own subtext to create meta references or irony. Story’s richest depths live in subtext. The best stories are about more than just the text. Their subtext offers thematic symbolism with the capability of turning even the simplest story into something deep and true. This is the power of allegory. It is the power of thematic metaphor. Even though all stories offer the potential for this, it actually takes a tremendous amount of courage for a storyteller to resist the urge to simply spell it all out.

When I speak about this, I think about movies like The Legend of Bagger Vance, The Lion King, and Forrest Gump. But even obviously blockbuster stories such as Jurassic Park and The Terminator elevate themselves into timeless and unforgettable experiences through their subtextual expertise. This stands in such blatant contrast to their resurrected franchise sequels—most of which, despite all their bling, are heartless, soulless, and (because you don’t get the first two without this one:) brainless.

Forrest Gump (1994), Paramount Pictures.

2. Mythic Structure and Archetypal Resonance

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

Mythological and archetypal underpinnings lay the foundation for stories of effortless truth. They point to what is most real, and they supply the kind of symbolism that takes audiences deep without even trying. Solid plot structure and character arcs start this off (as they are themselves rooted in myth and archetype), but there is so much more depth we can explore.

It’s true the old stories need to reinvent and resurrect themselves from time to time—or more strictly, culture needs to reinvent its relationship to these stories. We can get so close to them, we begin to think they are “tame lions” and we forget that what they really represent is something terrifyingly beautiful in its raw and primal power.

Our relationship to these structures evolves. But really it is us who evolves more than the structures themselves. I was reminded of this in recently viewing StudioBinder’s excellent retrospective of the Hero’s Journey (in which I was honored to appear):

It is arrogance that lets us think, in all our perky snark and world-weary cynicism, that we write the stories. No, the stories write us. We forget that at our peril, and as storytellers we, above all, safeguard the chthonic depths of our deepest, most terrifying, and most transcendent truths.

The great myths of our age have been movies (either first or perhaps most prevalently): Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Harry Potter. And they have changed us utterly. For this reason, if no other, I will never be content with even one single story that does not confront me, does not make me feel something, does not transform me.

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2 (2011), Warner Bros.

3. Emotional Sincerity, Vulnerability, and EarnestnessThis one isn’t always popular. But, honestly, I feel the truth of it deep in my bones: we are missing stories that confront us with emotional sincerity, with vulnerability, and, yes, with earnestness. We’re so jacked on sarcasm and skepticism. Perhaps it began as a tool to transform structures that had seen their day. But now, it’s starting to feel like a defense we’re just hiding behind.

There’s no hiding from hope—the hope that we will be seen, accepted, loved—not for who we are supposed to be, but just as we are in all our messy glory. Think about how hard it is to show up with your heart in your hand.

Although we certainly do see many films these days striving for this (and kudos to them), I can’t help feeling many are still hiding a bit behind their own weariness and tragedy. Sometimes simplicity and innocence and even happiness can feel the most vulnerable of all. I’m thinking of films like Big and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. These are simple—and in some ways very disruptive—comedic romps that reach far beyond themselves through their willingness to show up in the full earnestness of the human capacity for hope and faith.

Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), Paramount Pictures

4. Moral Clarity (With Nuance)Oh, yes, movies today have a certain moral clarity. At least, they like to tell you exactly what they think (see above about no subtext) and probably exactly what you should think too. Examples abound, from all perspectives. And, frankly, they’re all bad. But then we’ve also got a lot of post-modern confusion going on, and literally a slew of stories whose ambiguity leaves you wondering at the end if there even was a thematic message.

I’ve always liked to say, “Stories are better as questions than as answers.” I still stand behind that. Heavy-handed moralism goes hand in hand with no subtext, and it never works out well. But that doesn’t mean stories can’t (and shouldn’t) have something to say and to say it with all the conviction and nuance they can muster.

Think about Schindler’s List, Amadeus, every John Hughes film ever made, even Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure for crying out loud. These stories know what they are and what they’re trying to say about the world. They say it with assurance, and they offer the package up for us to have our own experiences and make our own judgements.

Schindler’s List (1993), Universal Pictures.

5. Joy and Wonder

Here’s another one that isn’t always praised in our modern film-going culture. But, by God, we need it. Of late, we have been in a time and a place where we have needed to stare down our shadows. But I think it’s time to remember why. Why do we face our shadows? What’s the point? Why is it worth it?

Every story faces its Point of No Return, its Moment of Truth, and its Dark Night of the Soul so it can emerge at the end transformed. The shadow transformed is always light.

I mentioned at the beginning of the article that it’s been a while since I’ve seen a film that really made feel something. If I’ve felt anything at all, it was probably some type of catharsis—grief, anger, shock, disgust. It’s been much longer since a film has taken me to that place of joy and wonder—that revelry just in being alive.

Star Wars did that for me, some of the early MCU movies did that, Secondhand Lions always does that. But these stories don’t have be romps. Joy is always waiting for us at the end of It’s a Wonderful Life, just as wonder waits for us at the end of Princess Mononoke.

It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), Liberty Films.

6. Goodheartedness

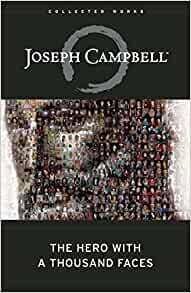

The Hero With a Thousand Faces Joseph Campbell (affiliate link)

Finally, I am reminded of what Joseph Campbell had to say about the quality of goodheartedness as a necessary quality of anyone who would succeed upon the Hero’s Journey. He spoke of the Irish folk hero Niall, who won his crown through the simplicity of goodheartedness as demonstrated in his kindness to a seeming old crone who was then transformed into the beautiful archetypal force capable of granting him the “Royal Rule.”

Now, don’t get me wrong. I am a friend to the shadows. I believe wholeheartedly in the necessity and courageous importance of facing our shadows—which, in so many ways, is what we are being called upon to do in this moment in time—and reintegrating them into a greater wholeness. All stories reflect humanity’s never-ending struggle with this transformative process. Some parts of the storytelling reflect one aspect; some another.

But even in the midst of our darkest shadow work, may we never forget the crucial piece that is goodheartedness. As storytellers, we bear the great burden of the world’s catharsis—the grief, the anger, our most violent and abhorrent proclivities. But part of that, too—and I would say the most important part—is also the tether to something deeper and truer and better and kinder.

May we write stories like Lord of the Rings and Anne of Green Gables and The Breakfast Club and E.T. and Little Women and Star Wars and Driving Miss Daisy and Harry Potter and Groundhog Day. May we write stories about the heroes we wish we were, the compassion we wish we had, the courage to transform, and the supreme gratitude with which to accept all the glory that is life.

Those are the movies I want to watch again. That’s how you put the whole world on a story high.

In Summary: Why Stories Must Find Their Heart AgainOver the past fifty years, storytelling has swung like a pendulum—from grit and cynicism to myth and wonder, and back again. Right now, we’re in a season of fragmentation, irony, and surface-level spectacle. But history suggests the cycle always turns. What’s missing today (and what audiences are aching for) is a return to sincerity, subtext, allegory, and stories that dare to make us feel something real.

Key TakeawaysModern movies often feel hollow because spectacle has replaced subtext.Storytelling moves in cultural cycles: grit → myth → irony → sincerity.We’re likely on the cusp of another turn toward earnest, mythic storytelling.Writers and filmmakers can be part of that shift by embracing sincerity, allegory, and goodheartedness.Want More?If this resonates, check out my Shadow Archetypes email course. Over eight weeks, we’ll explore the passive and aggressive shadow polarities of the six main archetypes in the Archetypal Life Cycle. It’s a deep dive into how the darker sides of our characters (and ourselves) shape narrative truth. You can sign up here.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think happened to modern storytelling? Do you feel the same hollow note I’ve described, or do you think the magic is still out there if we just know where to look? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post What’s Happened to Modern Storytelling? (+ 6 Ways Storytelling Can Find Its Soul Again) appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.