The 5 Types of Scene Endings Every Writer Must Master

There’s nothing quite like a scene that ends with a bang—or at least a purposeful beat that pulls readers deeper into the story. A well-crafted scene ending doesn’t just wrap things up, it launches momentum into the next scene, tightens your pacing, and deepens the emotional arc. Your scene might close in any number of ways, everything from a victory to a setback or a plot twist to a moment of quiet revelation. Whatever the case, scene endings create the impression that will (hopefully) carry readers into what comes next. Really, your writer’s toolbox doesn’t contain many tools more powerful than scene endings, yet they can be easily overlooked when it comes to tightening tension or strengthening overall story structure.

There’s nothing quite like a scene that ends with a bang—or at least a purposeful beat that pulls readers deeper into the story. A well-crafted scene ending doesn’t just wrap things up, it launches momentum into the next scene, tightens your pacing, and deepens the emotional arc. Your scene might close in any number of ways, everything from a victory to a setback or a plot twist to a moment of quiet revelation. Whatever the case, scene endings create the impression that will (hopefully) carry readers into what comes next. Really, your writer’s toolbox doesn’t contain many tools more powerful than scene endings, yet they can be easily overlooked when it comes to tightening tension or strengthening overall story structure.

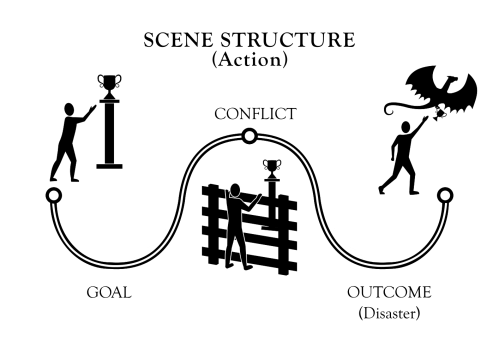

Classic scene structure breaks scenes into two broad halves: scene (action) and sequel (reaction). The scene half further breaks down into three primary pieces:

1. Goal (drives the action and intent of the scene as the character moves toward something).

2. Conflict (creates drama and complications by inserting obstacles that divert the smooth course of the character’s progression).

3. Outcome (shows the conclusion of the character’s efforts and reveals new complications leading to the next scene’s goal).

From the book Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

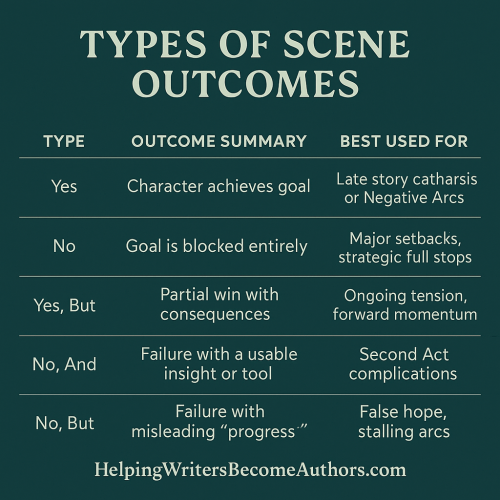

I have always emphasized the usefulness of two particular types of scene endings: the disaster (“no, and”) and the “yes, but” disaster. Today, I want to go deeper by breaking down five key types of scene endings—“Yes,” “Yes, But,” “No,” “No, And…,” and “No, But…”—and exploring how choosing the right one can keep your story flowing and your readers hooked.

In This Article:Why Ending Your Scenes Well Is Crucial for Pacing and TensionThe 5 Types of Scene Endings Writers Must Know (With Examples)“Yes” – Characters Get What They Want“No” – Characters Are Shut Down“Yes, But” — Small Victory With Complications“No, And…” – It Gets Worse, But There’s Hope“No, But…” – The Danger of False ProgressEnding Your Scenes With IntentionWhy Ending Your Scenes Well Is Crucial for Pacing and TensionFirst of all, let’s consider why we have scenes in our stories at all. Why not just one mad rush of action leading to the end? Although we could perhaps argue this a few different ways, the ultimate reason scenes are important in storytelling is the same reason any kind of structure is important: it creates and controls the pacing. And pacing, as I have shared before, is basically the writer’s version of the cool Jedi trick of mind control.

More than almost any other technique in fiction, pacing allows us to guide the audience’s experience. This is perhaps nowhere more true than of scene endings—which give audiences the opportunity to put the story down… or keep going. If you convince them to keep going, that means they’re enjoying themselves—and the more they’re enjoying themselves, the more likely they will stay all the way to the end.

Two Ways to Think About Scene EndingsThe outcome taking place at the end of the scene structure (discussed above).Any obvious break in the narrative—such as a chapter or commercial break or even just the subtle division of a scene break on the page.It’s important to notice that the two may be the same, but don’t have to be. A structural scene is defined by the pieces that make up its whole (scene and sequel, with all their smaller parts), while chapters and “scenes” (as dictated by visual scene breaks on the page) can be of whatever length is most useful to the pacing. A structural scene may expand across many chapters or a single chapter may contain multiple structural scenes.

>>Read more here: 7 Questions You Have About Scenes vs. Chapters

For our purposes today, we’re mostly focusing on the outcome of a structural scene. Why? Because these moments move beyond simple hooks or tricks used to tease audiences. Importantly, structural scene outcomes are always important turning points that advance the plot. The only way the plot is ever advanced is by something changing in the narrative—i.e., whatever scene goal the character just enacted cannot be enacted once again in exactly the same way. Something has changed. This could be simply that the character learned how to try again in a better way, or it could be that a major setback or achievement was reached that significantly altered the goal itself.

It’s also worthwhile to note that the idea of a scene “goal” does not necessarily insist that characters know exactly what they want and move toward it with single-minded focus. Sometimes the forward momentum implied by the idea of a “goal” is better recognized as simply an “intent” on the characters’ parts. They may be moving in a particular direction, but they may also (depending on the needs and tone of the story) simply be leaning in a certain direction.

Either way, what is most important is that this forward intent is met with some level of conflict. Here, too, it’s important to understand conflict in its broader sense. Conflict need not necessarily mean a confrontation or any hint of violence (i.e., something so slight as a disagreement on one end of the spectrum escalating into physical chaos on the other). Rather, conflict is best understood simply as something that impedes the scene’s forward momentum. Conflict is an obstacle creating the further complications or consequences that eventually change the character’s position within the narrative—thus changing the plot.

This change of situation is what then leads into the end of the scene—the outcome—which can show up as several different possibilities. Each possibility will impact your story’s pacing, flow, and function in different ways, which is why it’s important to understand all of them, the consequences they create, and which is best suited to any particular scene ending in your story.

The 5 Types of Scene Endings Writers Must Know (With Examples)So what are the best types of scene endings in fiction? Some endings slam the door shut. Others crack it open. Some fling it off its hinges and send your characters stumbling into the next chapter! What’s most important is that the scene’s outcome matters. It creates consequence, change, and momentum.

Let’s break down the five primary types of scene endings and explore how each one functions in your narrative (and why some are stronger choices than others).

The five types of scene endings are “Yes,” “No,” “Yes, But,” “No, And,” and “No, But.”

1. “Yes” Scene Ending — Characters Get What They WantThis one’s straightforward: characters set out to achieve a goal in the scene, and they succeed. (Yay!) Sometimes “yes” endings can be deeply satisfying. However, they must be used with caution and awareness as they risk deflating tension. Usually, ultimate success is reserved only for the end of the story. This is for the simple reason that once the character has definitively succeeded (or failed) to reach the overall story goal, the plot is over. If your characters’ progress toward that ultimate goal is left unimpeded for too long, the plot will quickly run its course.

Of perhaps even greater concern is that “yes” scene endings don’t always generate new questions or consequences for the characters to explore in subsequent scenes. Usually, “yes” scene endings are most appropriate later in the plot when you’re wanting to show characters getting closer to achieving their final success. “Yes” scene endings can also be used for catharsis late in the story to relieve some of the tension you may have built—such as when romantic couples finally get together in a positive and love-affirming way (even if their struggles in the main plot haven’t yet been fully resolved).

Ironically, “yes” scene endings can be more appropriate in Negative Change Arc stories than in Positive Change Arc stories. This is because when a character is headed for a bad end, the successes achieved on the scene level ultimately lead to greater accumulated consequences down the line.

For Example:

In The Great Gatsby, when Gatsby finally reunites with Daisy at Nick’s house, he achieves his goal of finally meeting with her. The scene ends with Gatsby glowing in his long-awaited triumph. No real conflict derails the scene goal, and Gatsby doesn’t have to pay any immediate price. He gets exactly what he wants, and in that moment, it feels like success.

The Great Gatsby (2013), Warner Bros.

2. “No” Scene Ending — Characters Are Shut DownBy contrast, in a “no” ending, characters are stopped cold. The movement toward the goal isn’t just complicated, it’s outright blocked. No progress whatsoever is made. “No” scene endings can be effective for shooting the stakes sky-high. However, they should also be used with caution. Too many in a row means the plot can make no progress since characters never get any closer to the overall story goal. More than that, the absoluteness of “no” endings can make it difficult for characters to regroup or gather enough context to try again in a different way.

“No” endings often bring the narrative to a screeching halt. This is rarely a good plot device, since it actually kills tension instead of building it. In essence, if a “yes” ending deflates conflict by giving the protagonist a win, the “no” ending kills the conflict by instead giving the antagonistic force the win. There aren’t a lot of options for the protagonist after a solid “no” ending.

One of the only times a hard “no” ending might be desirable is when you do, in fact, want to screech the plot to a halt for a bit, as would be the case if you wanted to return to deeply traumatized or disillusioned characters after a passage of time in order to watch as they pick themselves back up.

For Example:

The Empire Strikes Back ends with a pivotal “no” when Luke Skywalker confronts Darth Vader in Cloud City. Luke’s goal is clear: defeat Vader and save his friends. Not only does he fail to defeat Vader, he loses his hand and is hit with the devastating reveal that Vader is his father. Physically, emotionally, and psychologically, he is stopped cold. The scene doesn’t just complicate things, it shuts the door completely. He escapes only by falling into the void. And after this moment, the plot does screech to a halt for a time between episodes, which allows the necessary space for Luke to reflect, regroup, and build into a new approach in Return of the Jedi.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

3. “Yes, But” Scene Ending — Small Victory With ComplicationsOne of the most useful scene endings is the “yes, but” outcome. This one mixes elements of victory and defeat to deepen the narrative. On the one hand, the characters’ efforts achieve a “yes”—they get some or all of what they wanted in the scene. On the other hand, they are met with a “but”—their gain comes with complications or consequences.

This approach is particularly effective since it allows the plot to move steadily forward thanks to the characters’ achievement of scene goals on the path toward the larger story resolution. It also ensures the plot can’t end too quickly, thanks to the complications that prevent a clean victory. For instance, perhaps the characters get half of what they want, but that means they also don’t get half of what they want. Or perhaps they get exactly what they sought in this scene, but doing so raises the stakes or gets them into trouble, which can then prompt a new goal in the next scene.

From a pacing perspective, the “yes, but” scene ending is great since it gives the audience little hits of satisfaction as the characters receive yummy rewards, but it also ramps tension and keeps readers reading since these rewards complicate either the characters’ lives or their forward progress toward the ultimate catharsis of the Climactic Moment. In truth, this type of scene ending is so useful and versatile, you could easily use it for every scene outcome all the way to the end.

For Example:

The Fellowship of the Ring offers a great “yes, but” during the Council of Elrond when Frodo volunteers to take the Ring to Mordor. Although Frodo’s goal in that moment isn’t fully conscious, his intent is clear: he wants to do the right thing, stop the Council’s squabbling, and take responsibility for the burden he’s been given. He succeeds when the Council accepts his offer in a definitive “yes.” The complications, however, are enormous as this decision definitively turns the plot by launching Frodo onto a long, dangerous road filled with escalating threats.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), New Line Cinema.

4. “No, And…” Scene Ending — It Gets Worse, But There’s HopeWhat’s the difference between a “yes, but” and a “no, and” scene ending? The “no, and” scene ending is similar to the “yes, but” ending, but flips the script. Here, instead of mostly succeeding, characters mostly fail. However, the failure is not complete. Out of the rubble of failure, scraps of insight or hope emerge. Some small bit of ground is gained.

The “no, and” scene ending is the classic “cup half full.” Everything’s gone to pot, yet characters are still able to salvage some small win. They find a way forward through the mess or latch onto the bit of knowledge learned from their mistakes. Whatever the case, the most important thing to leverage about a “no, and” ending is that it moves the plot. The only way it can do that is by changing something for the characters. Even though they may have spectacularly failed to gain what they wanted, they now have some tool or clue that allows them to try again but in a different way.

“No, and” endings can’t be used as exclusively as “yes, but” endings (unless your story leads to your characters’ ultimate failure), but they can be used liberally, especially in the Second Act, to increase tension, raise the stakes, and create interesting dynamics for prompting characters to evolve.

For Example:

The Martian by Andy Weir features a great “no, and” scene ending when protagonist Mark Watney tries to make water to grow his crops and accidentally blows himself up. His goal was simple: create a livable environment using chemistry and ingenuity. The scene ends in failure. However, in the aftermath, he figures out what went wrong, recalibrates his approach, and gains critical information about how to proceed more safely next time.

The Martian (2015), 20th Century Fox.

5. “No, But…” Scene Ending — The Danger of False ProgressThis is the trickiest one. In a “no, but” ending, characters fail to get what they want, but walk away with something that seems helpful—until it turns out it’s not. “No, but” scene endings creates the illusion of movement without true momentum. As a plot device, this is never particularly useful since it never actually moves the plot, no matter how much it may look like it does. It creates dead ends in which characters spend time working on a seeming solution—only to end up exactly where they started back before the original “no, but” scene. The result can be a “busy” plot that actually goes nowhere.

The “no, but” outcome may be used very occasionally with purposeful effect to emphasize a character’s current refusal to learn and/or to face consequences or personal blind spots. It can also be used to deepen tension and despair in certain situations, in which a character is clinging to false hope—such as in disaster stories in which characters think they have found a way out of their peril only to realize it was a mirage. Used sparingly, this kind of scene can underscore a character’s stuckness or false sense of growth.

For Example:

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade features a solid “no, but” scene early on when Indy fails to recover the Cross of Coronado from the treasure hunter who stole it. He’s given a token “win” when the local authorities thank him and the museum director tells him, “At least you tried.” However, although it may feel like he’s accomplished something or at least clarified his purpose, the artifact is still gone. He’s no closer to recovering it than he was before. This isn’t progress. The “but” gives the illusion of development, but the narrative is effectively paused until the real plot kicks in with the Grail storyline.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), Paramount Pictures.

Ending Your Scenes With IntentionAs with most writing techniques, the power of scene endings lies not simply in recognizing the options, but in knowing how and when to use them. The way you close a scene determines how your story moves forward. This is true whether you’re building tension, paying off a moment of catharsis, or giving your characters one more reason to grit their teeth and keep going. If your scene endings feel flat, confusing, or disconnected, chances are your plot is suffering too. However, when you choose your outcomes with intention by aligning them with character goals, story structure, and pacing, you can create a reading experience that feels cohesive and alive with momentum.

In SummaryScene endings are structural turning points that determine your story’s pacing, tension, and sense of movement. Choosing the right type of outcome, whether it’s a clean win, a total failure, or something sneakier in between, can keep your plot evolving and your readers fully engaged.

Key TakeawaysEvery structural scene ends with an outcome that determines the story’s forward momentum.The five main types of scene endings are: “Yes,” “No,” “Yes, But,” “No, And,” and “No, But.”“Yes” scene endings create character success but can flatten tension if overused.“No” scene endings end in total failure and must be used sparingly to avoid stalling the plot.“Yes, But” scene endings are the most versatile, combining satisfaction with escalating tension.“No, And” scene endings emphasize failure but give characters new tools or insight to try again.“No, But” scene endings create only the illusion of progress and should be used sparingly to avoid plot dead ends.Want More?

Structuring Your Novel: Revised and Expanded 2nd Edition (Amazon affiliate link)

If you’re ready to take a deep dive into the mechanics of scene structure, including how to seamlessly integrate your scene and sequel halves, check out my book Structuring Your Novel. Not only will it teach you how to structure a solid plot, it’s packed with practical tools and intuitive frameworks to help you build scenes that keep readers reading. It’s available in e-book, paperback, and audiobook.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Which of these five scene endings do you find yourself using most often? Are there any you tend to avoid? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post The 5 Types of Scene Endings Every Writer Must Master appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.