K.M. Weiland's Blog, page 8

April 22, 2024

How to Use Symbolic and Archetypal Settings in Your Story

Story settings serve as the backdrop, providing a tangible environment in which characters interact and events unfold. Most settings are realistic and straightforward, providing physical attributes of necessary locations in the story. But writers can raise stories to a higher level by employing symbolic and archetypal settings that go beyond mere description to act as metaphors for abstract concepts, emotions, or themes.

Story settings serve as the backdrop, providing a tangible environment in which characters interact and events unfold. Most settings are realistic and straightforward, providing physical attributes of necessary locations in the story. But writers can raise stories to a higher level by employing symbolic and archetypal settings that go beyond mere description to act as metaphors for abstract concepts, emotions, or themes.

As representatives of the collective human experience, symbolic and archetypal settings enable writers to explore profound themes, create resonance, and immerse audiences in narratives that transcend the confines of the tangible world. Symbolic settings imbue narratives with layers of meaning, allowing writers to convey emotions, themes, and abstract concepts. Taken a step further, archetypal settings tap into shared cultural symbols and myths, offering familiar frameworks that connect deeply with readers.

Over the last few years, I have taught quite a bit about the power of archetypal stories. Specifically, in the many articles on this site, in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs, and in my recent Shadow Archetypes course, I have talked about how character archetypes can be used to create potent character arcs. Inherent to all those discussions are many other archetypes and symbols. If you’ve read the beat sheets I’ve provided for the six primary archetypal journeys, then you know they are steeped in mythological and metaphorical language. Something I’ve touched upon in those discussions but never directly addressed are archetypal settings.

A while back I received the following email from Matt Wright:

I’ve been looking into “setting archetypes” as tools for writers to use in their stories but haven’t found much out there. Symbolism.org calls it “Place Symbolism.” … I wonder if you have any thoughts on this?

Today, I thought it would be fun to dive deeper into this topic. Setting is such a crucial element within fiction. Often, we will refer to it as “a character in its own right.” When done well, setting exists as so much more than simply a physical background designed to convince readers of a certain degree of realism. Rather, setting functions as context for everything in a story, which is what, in turn, deepens the opportunity for thematic subtext.

>>Click here to read “How to Choose Story Settings: The 4 Basic Types of Setting”

Although setting’s ability to offer commentary upon the rest of the story can, and often will, arise naturally from the writer’s own subconscious during creation, it is valuable to bring a deeper understanding to the symbolic and archetypal possibilities available for your stories’ settings.

There is much overlap between symbolic and archetypal settings. The distinction lies in contrasting their respective scope and significance.

A symbol is a specific object, image, or element that represents a broader, often abstract idea, theme, or concept. It carries meaning beyond its literal interpretation and can evoke emotions or convey complex notions within the context of a story. Symbols are versatile and can vary in interpretation across different cultures and contexts.

On the other hand, an archetype is a recurring pattern, character, theme, or setting that embodies universal symbols and resonates similarly across cultures and time. Archetypes are deeply rooted in collective human experiences and myths, representing fundamental aspects of the human psyche. They serve as timeless, recognizable molds that shape characters, narratives, and settings, providing a shared framework for how we understand and interact with stories.

While a symbol is specific and context-dependent, an archetype is broader and taps into the fundamental, archaic elements of storytelling that transcend individual tales. In essence, symbols are components within a narrative, while archetypes are overarching, recurring motifs that underpin the very structure of stories.

What Are Symbolic Settings?Almost every story you can think of features a setting that qualifies as symbolic. Indeed, sometimes the entire story will be created around a specifically symbolic setting. This needn’t be overt. Although a story such as Labyrinth may be obvious in using its titular setting to explore the inner maze of the evolving self, stories such as Gilmore Girls or Sweet Magnolias may use the cozy confines of a small town to symbolize safety, support, and friendship in a much more natural and invisible way.

Sweet Magnolias (2020-), Netflix.

Even stories that aren’t explicitly aware of their own symbolism often end up using settings that reflect characters’ moods or internal struggles. For example, graveyards are commonly used as backdrops for explorations of grief, terror, or mortality.

A skilled writer who is conscious of the power available in setting will tweak settings to create important symbolism. For example, both the James Bond and Jason Bourne movies are about globe-trotting spies, but the way the international settings are used evoke totally different moods and metaphors to support the respective characters’ personal journeys.

The Bourne Identity (2002), Universal Pictures.

Following are some of the more common symbolic settings you might use in your stories.

1. Maze or LabyrinthRepresents the journey of self-discovery, challenges, and the complexity of life.

For Example: Labyrinth, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Maze Runner, Inception

Inception (2010), Warner Bros.

2. ForestSymbolizes mystery, danger, the unknown, themes of transformation and growth, healing, connection to nature, and harmony.

For Example: The Lord of the Rings, Where the Red Fern Grows, Princess Mononoke, Robin Hood, Where the Wild Things Are

Princess Mononoke (1997), Studio Ghibli.

3. DesertConveys isolation, hardship, emptiness, and spiritual journey.

For Example: Lawrence of Arabia, The Ten Commandments, Dune, Mad Max: Fury Road, The Alchemist, The English Patient

Mad Max: Fury Road (2015), Warner Bros.

4. CaveRepresents secrets, hidden truths, self-reflection, and the concept of rebirth.

For Example: The Empire Strikes Back, The Descent, Plato’s allegory of “The Cave.”

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

5. Castle or FortressSignifies power, authority, protection, and can also represent imprisonment or confinement.

For Example: Dracula, The Last Castle, Harry Potter, Beauty & the Beast

Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), Warner Bros.

6. Ocean or SeaSymbolizes the subconscious, vastness, exploration, the unknown, and the mysteries of life.

For Example: Life of Pi, Moby-Dick, The Old Man and the Sea, Moana, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, Finding Nemo, Cast Away, Ponyo

Moana (2016), Walt Disney Pictures.

7. IslandRepresents solitude, isolation, self-discovery, and serves as a microcosm reflecting society.

For Example: Lord of the Flies, Robinson Crusoe, Swiss Family Robinson, The Tempest, And Then There Were None

Lord of the Flies (1963), British Lion Film Corporation.

8. CityscapeCaptures the essence of modern life, complexity, anonymity, and the opportunities and challenges of urban existence.

For Example: Blade Runner, Metropolis, West Side Story, The Great Gatsby

West Side Story (2021), 20th Century Fox.

9. MountainsSignifies challenges, obstacles, spiritual ascent, and isolation.

For Example: Into Thin Air, Seven Years in Tibet, The Mountain Between Us.

Seven Years in Tibet (1997), Sony Pictures.

10. RuinsEvokes themes of decay, the passage of time, and the aftermath of civilization.

For Example: The Road, I Am Legend, Indiana Jones, City of Ember, The Time Machine

The Road (2009), 2929 Productions.

11. GardenSymbolizes Eden, innocence, the healing power of nature, and personal growth.

For Example: The Secret Garden, The Gardener

The Secret Garden (2020), StudioCanal.

12. TunnelsSignifies hidden truths, the passage between worlds, and the exploration of the subconscious.

For Example: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Pan’s Labyrinth, The Great Escape

The Great Escape (1963), The Mirisch Company.

13. Outer Space

Represents infinity, the unknown, exploration, and the cosmic forces that shape human existence.

For Example: 2001: A Space Odyssey, Solaris, Interstellar, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, The Martian, Ender’s Game

The Martian (2015), 20th Century Fox.

What Are Archetypal Settings?Archetypal settings make use of symbolism, but take everything to a deeper place. In part, this depth is achieved through the shared understanding between writer and readers that the archetype represents not just thematic resonance, but a potential initiation of the psyche.

Archetypal settings may be literally archetypal in their presentation. For example, you may represent the Underworld in your story as Hades or some other equivalent. But it can also be represented more symbolically. In some stories, an underground tunnel, a graveyard, or the criminal “underworld” may be understood to represent more than just the setting’s practical function within the story.

An archetype holds the quality of transformation and transcendence. It represents the thresholds of the human experience—aka, the big changes in life, the moments that forever shift our perspectives. We may all walk by a hundred cemeteries in our lives. We may even connect to the shared symbolism of grief and the recognition of our mortality when we visit them for loved ones’ funerals. But none of these casual encounters will necessarily invoke the transformational archetype experienced by Ebenezer Scrooge in A Christmas Carol‘s use of this setting to catalyze permanent change.

Mickey’s Christmas Carol (1983), Walt Disney Pictures.

Here are some examples of possibilities for archetypal settings in your stories:

1. The UnderworldRepresents the descent into the dark realm, representing either Death or the shadows of the unconscious mind. To go there and return is indicative of the archetypal experience of Death/Rebirth.

For Example: The Inferno, Corpse Bride, What Dreams May Come, Coco, Soul

Corpse Bride (2005), Warner Bros.

2. Garden of EdenAn idyllic, perfect setting that often symbolizes innocence and sets the stage for temptation and awakening. It is indicative of the archetypal experience of Innocence and Innocence Lost.

For Example: Paradise Lost, The Giver, Avatar, The Magician’s Nephew, The Poisonwood Bible

Avatar (2009), 20th Century Fox.

3. The KingdomThe archetypal seat of power, representing authority, leadership, and often the central location for epic tales. It represents the central archetype of psychological transformation, representing the Self. Its relative state of corruption or safety indicates the lessons to be learned in the story.

Example: The Grail legends, Lord of the Rings, Game of Thrones, The Lion King, Ella Enchanted, The Princess Bride

The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King (2003), New Line Cinema.

4. WildernessA vast, untamed environment symbolizing both danger and the potential for self-discovery. It is indicative of the archetypal experience of descending into one’s shadow or unconscious on a quest for personal growth and wholeness.

For Example: The Call of the Wild, Wild, The Revenant, The Edge

Wild (2014), Fox Searchlight Pictures.

5. The WastelandA barren, desolate landscape representing decay, loss, and the need for renewal or rebirth. Can share attributes with the ocean and the desert. It is indicative of the archetypal experience of confronting corruption and mortality.

For Example: Mad Max: Fury Road, The Road, The Book of Eli, The Grapes of Wrath, Children of Men, The Walking Dead, Chernobyl

Children of Men (2006), Universal Pictures.

6. Dream WorldA surreal, fantastical world accessed through dreams or imagination, often challenging reality. Can also be a “mirror world,” paralleling reality in some telling way. It is indicative of the archetypal experience of confronting the unclaimed shadows of one’s unconscious—looking at what one doesn’t want to look at or confronting one’s fears.

For Example: Inception, The Wizard of Oz, Spirited Away, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, and my own Dreamlander

Spirited Away (2001), Studio Ghibli.

7. Temple or Sacred SpaceA place of reverence and mystery, representing spiritual or sacred knowledge. It is indicative of an encounter with the divine, with archetypal Wisdom or Love, or sometimes just with a form of higher intelligence.

For Example: Seven Years in Tibet, Stargate, The Last Crusade, The Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Shack

The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1996), Walt Disney Pictures.

8. The City of GoldA mythical city symbolizing the pursuit of wealth, success, or an idealized destination. It is indicative of an archetypal encounter with the ego, all that one desires or identifies with and all its subsequent temptations.

For Example: The Road to El Dorado, Atlantis: The Lost Empire, Lost Horizon, Treasure of the Sierra Madre, Lost City of Z

Atlantis: The Lost Empire (2001), Walt Disney Pictures.

Archetypal Settings in the 6 Life ArcsThe symbolic and archetypal settings listed above are only a sampling of those available for you to use in your stories. Writers often instinctively choose the right archetypal setting to represent the central conflicts and themes of their characters’ journeys. Sometimes it will even turn out that a setting you thought you chose for practical reasons is the perfect metaphor and catalyst for your story’s deeper explorations of psyche and spirit.

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

In my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs, I explored the six primary arcs of the human life cycle, each representing a significant initiation, beginning with the Maiden’s coming of age and traveling all the way through to the Mage’s surrender of life. These stories (of which the Hero’s Journey is the second) are deeply powerful frameworks upon which to build plots that tap the archetypal foundations we share with our readers.

If you are interested in writing one of these arcs (which you can explore in more depth here), you may be particularly interested in mapping out the specific archetypal settings inherent to each one.

1. The Maiden: HomeThe Maiden Arc begins in the Protected World of her early residence and takes her into the Real World beyond its boundaries. Although this transition can be dramatized via any number of possible symbolic settings, the primary archetypal setting around which her entire journey revolves is that of the Home.

Specifically, this is the Home of her childhood, the home of her parents or caretakers. In certain types of stories, this may not be represented literally, but it should evoke the sense of being relatively safe and cared for. The Maiden’s growth arc is that of moving beyond the controlling protection of her authorities into responsibility for herself and her own well-being. The Home setting symbolizes everything she risks losing in this transformation, as well as the constrictions of childhood she is being called to leave behind.

For Example: Ever After, Bend It Like Beckham, The Truman Show, Little Women

Ever After (1998), 20th Century Fox.

2. Hero: Village/RoadThe Hero Arc begins in the Normal World of the First Act and takes him into the Adventure World of the Second Act. The archetypal setting that frames both these symbolic words is the Village. Best known from classic portrayals of the Hero’s Journey, such as those originated by Joseph Campbell and Michael Vogler, the Village represents the home the Hero shares with his tribe. It is the place from which he leaves to embark on the Road during his quest; indeed, it is the place he specifically leaves to protect. And it is the place to which he will return with the healing elixir at the end after overcoming the Dragon.

Although the Village may be literally represented by a small town, what it symbolizes is community. Like the Maiden’s Home, the Village encompasses both the stifling qualities the Hero wants to leave behind and must fully individuate from, but also the redemptive and loving qualities that will inspire him to return with aid and to re-integrate as a healthy member of society. The Road, with all its dangers, will provide the Hero with the adventure he craves, the experience he lacks, and ultimately the perspective required to find his place within the Village.

For Example: Mulan, Treasure Island, The Goonies, Back to the Future

Back to the Future (1985), Universal Pictures.

3. Queen: Hearth/KingdomThe Queen Arc begins in the Domestic World of the First Act and takes her into the Monarchic World. She will begin at the Hearth, a cozy space not unlike the Maiden’s Home, but with the difference that the Queen is ruler of this little world. The Hearth represents her great loving heart and her capacity to care for others. She will then be challenged to grow into greater leadership by stepping beyond the Hearth into the wider Kingdom.

Although the Kingdom can be seen as an archetypal backdrop for all the archetypal arcs (or, really, any story), for the Queen the symbolism of the Kingdom is specifically pertinent, as she is challenged to take the throne of her story’s world. The Kingdom represents a broadening of her influence. She moves from being responsible for a family or perhaps the Village to now taking charge of a much vaster realm. The contrast between Hearth and Kingdom is striking, and the transition is not always an easy one, as embracing the power of the Kingdom often feels like sacrificing the comforts of the Hearth.

For Example: Elizabeth, A League of Their Own, The Incredibles, 42

Elizabeth (1998), PolyGram Filmed Entertainment.

4. King: Palace/EmpireThe King Arc begins in the Regal World and takes him into the Preternatural World. The foundational setting archetype for the King is that of the Empire he rules, which is often symbolized on a smaller level by the Palace in which many of the scenes take place. Although the King may venture outside the Palace, he will not venture outside his Empire. Rather, the great Cataclysm that threatens his reign will infiltrate his realm and come to him.

The Cataclysm itself can be viewed as a sort of setting—as an apocalyptic stormscape of sorts—that alters the base setting of Empire, turning what was once safe and protected into someplace dangerous and uncertain. The King’s arc will evolve him into a surrender of his power and an exit from the world stage. The supernatural aspects of the Preternatural World may be represented by grand archetypal settings, but more likely by the inner landscape of his own mind.

For Example: Casablanca, Iron Lady, Braveheart, Black Panther

Black Panther (2018), Marvel Studios.

5. Crone: Hut/UnderworldThe Crone Arc begins in the Uncanny World and moves to the Underworld. Symbolically, a Hut in the dark forest best represents the Crone’s starting place. She begins in a comparatively small and confined physical space—symbolizing, in part, the comparative smallness and constriction of her own diminishing physicality. From there, she will begin to explore her potential for psychological and spiritual vastness.

The Underworld is the crucial archetypal setting for the Crone. It represents her central challenge of confronting Death, via her own mortality, and discovering the hope necessary to still embrace Life. Although the Underworld may, of course, be dramatized literally, it may also be represented quite subtly. What is important is that it brings with it that sense of the uncanny—the sense of moving beyond the ordinary into non-ordinary reality.

For Example: Howl’s Moving Castle, Our Souls at Night, Up, Paladin of Souls

Howl’s Moving Castle (2004), Studio Ghibli.

6. Mage: CosmosThe Mage Arc begins in the Liminal World and moves to the Yonder World. What is meant by this is that the Mage begins already with a broadened perspective that allows him to see the greater truths of Life and to look beyond into the even greater truths of Death. From there, the arc of his story will eventually take him beyond this world, into the “Yonder.” His realm is bigger than simply the practical concerns of the Queen’s Kingdom or the King’s Empire; he understands that these domains are but tiny pieces of the larger Cosmos.

However, as big as the Mage’s archetypal setting can indeed be, it is often represented more practically by the much smaller archetypal settings of previous archetypes. The Village, Kingdom, and Empire can all be on the map of his journey, as he travels to help younger archetypes with their own challenges. What is most important in choosing the Mage’s archetypal settings is that they contrast the physical limitations with his own understanding of himself as a “citizen of the Cosmos,” as someone who is “in the world, but not of it.”

For Example: Miracle on 34th Street, Mary Poppins, The Legend of Bagger Vance, Star Wars: A New Hope

***

While all stories find grounding in realistic descriptions, the magic of symbolic and archetypal settings shapes a narrative’s very soul. Symbolic settings transcend the literal, weaving layers of meaning into the narrative fabric, while archetypal settings tap into the symbols, resonating across cultures and epochs. As conduits of collective human experiences, these settings unlock profound themes that transport audiences into the realms of metaphor and myth. Each symbol and archetype serves as a portal, inviting readers on a transformative journey.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What symbolic and archetypal settings have you used in your stories? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Use Symbolic and Archetypal Settings in Your Story appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 15, 2024

Checklist for Beginning Your Story: Plot Considerations

Welcome to this week’s post, which is a continuation of what we talked about in last month’s video when we started a checklist of important elements to consider for your story’s beginning. Last time, we specifically talked about what you need to consider in regards to character and all of the many elements you can use both to enhance character in the beginning and to use character to create an awesome beginning that hooks readers.

Welcome to this week’s post, which is a continuation of what we talked about in last month’s video when we started a checklist of important elements to consider for your story’s beginning. Last time, we specifically talked about what you need to consider in regards to character and all of the many elements you can use both to enhance character in the beginning and to use character to create an awesome beginning that hooks readers.

I talked in that video about how complex a topic beginnings are and how the first chapter has so many moving pieces and so many things to think about, not just in hooking readers and convincing them this is an entertaining story, but also in laying the groundwork for everything to follow. If your beginning can’t do all that, then it compromises the story that follows.

So I wanted to divide this topic into two posts (and you can also watch the video or listen to the podcast, if you prefer those mediums). Really, there’s so much to talk about and we’re not covering all of everything that there is to consider about beginnings.

>>Click here to read “Your Ultimate First Chapter Checklist, Pt. 1: Hooking Readers“

>>Click here to read “Your Ultimate First Chapter Checklist, Pt. 2: Writing the Opening Scene“

>>Click here to read “Your Ultimate First Chapter Checklist, Pt. 3: Introducing the Story“

Today, we are going to be talking about plot considerations for your story’s beginning.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

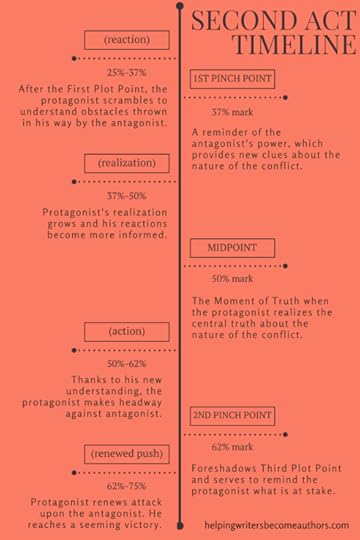

Obviously, character is a huge part of this. You can’t have plot without character. Beginning with some of the things we talked about in the last video as a foundation is important in creating or highlighting elements of your character’s personality that drive the conflict and show your character’s relationship to the thematic Lie and Truth, which are going to drive their character arc and influence what they want and how they interact in the plot.

Setting Up Your Character’s Plot Goal in Your Story’s BeginningOne of the first things to remember in introducing the plot in your story’s beginning is that every scene in your story is like a domino in a row of dominoes. You know how people create those really elaborate designs, where if you push one domino over, it creates this chain reaction? Every domino has to be perfectly in place for this to happen, or the action comes to a halt and, at best, the person has to come in and manually bump over the next domino to recreate the chain reaction.

The first domino in your plotline of dominoes is the first scene. Ask, “How does this set up the chain reaction that’s going to follow?” It can’t be this arbitrary scene that’s tacked on in order to accomplish other important things that have to happen in the beginning (such as introducing characters or even just hooking readers). It has to do so in a way that is integral to the entire story and that creates this sense of cohesion and resonance.

Setting Up Your Character’s Desire and Plot GoalWhat is plot in a nutshell? We can simply think of it as the character wanting something. They have a goal, and that goal is met with obstacles, which is what creates the conflict and therefore the entire drama of the story. It all begins with something your character wants.

This desire is something specific. It’s the plot goal, whatever that may be in your story, whether it’s a relationship (i.e., they want to be with somebody), whether it’s an actual item they’re pursuing that they need, or whether it’s to defeat an enemy. The plot goal can be something very specific (i.e., something they can hold it in their hand), or it can be something more abstract. Whatever it is, it is something specific within the plot. That specific goal is driven by a deeper desire on your character’s part. This is the Thing Your Character Wants.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Setting Up the Thing Your Character WantsThis is important to consider when setting up your first chapter, because the plot goal will continue to gel as the story goes along. Particularly throughout the First Act, the goal may not be something the character specifically is after or even knows about necessarily. It may not fully come into view until the beginning of the Second Act, but you still have this whole first part of your story that you have to fill with stuff that has to happen. These events need to engage readers and make them want to read on until they get to that full immersion in the story’s drama.

So what do you do? What drives the plot in this early part of the story? Again, the answer is the Thing Your Character Wants. This is a deeper desire. It’s a deeper Want that fuels the desire and the need for that plot goal. As the story progresses, this desire will funnel into something that’s more specific. But this initial Want is founded upon and driven by the character’s relationship to the thematic Lie the Character Believes.

The Lie is a limited perspective the character holds—a limiting belief about themselves or the world they live in—that is motivating their actions in a way that is ultimately dysfunctional. It becomes increasingly so within the events of your specific story. Think about in this first scene as you’re crafting. What is the Thing Your Character Wants?

Even if you’re not yet able to craft an opening scene that is specifically involved with the plot goal that will come to light later on, you can still craft a scene based around the character’s desire, around the Thing Your Character Wants in this opening scene. In so doing, you get the opportunity to dramatize their relationship to the Lie and their relationship to the Normal World.

>>Click here to read “What Does Your Character Want? Desire vs. Plot Goal vs. Moral Intention vs. Need“

Setting Up the Thing Your Character NeedsYou can also think about the Thing Your Character Needs, which contrasts the Want. Generally, the Thing the Character Needs is the thematic Truth, which the character will come to believe as the story goes on. The Truth is the more expanded mindset contrasts the limitations with which they start out. Obviously, they don’t have the Truth in the beginning of the story. They may never get the Truth, depending on what type of arc they’re following. In a Positive Change Arc, they won’t fully integrate the Truth until the end of the story.

Use your awareness of the Thing the Character Needs—and their lack of it—to show how they’re interacting with the Thing the Character Wants. How are they trying to pursue the Want as a replacement for the Need?

A basic example of this would be that the character needs to let somebody love them, but their want is to fill that need with other things. Maybe they want to be a pop star. They think they want fame when what they need is love. Maybe the story is about falling in love or maybe it’s about reuniting with an estranged parent or something like that, the events of which will help the character evolve their perspective of and their relationship to love and to themselves and to loving themselves ultimately. You’re setting up this plot in which they’re pursuing a mistaken mode of trying to get love via their pursuit of fame. They start out thinking, I’m going to become a famous pop star and everybody’s going to love me! That kind of thing. Set that up in the very first chapter, even as you’re waiting to fully bring in the dynamics that will challenge that mindset and make it difficult for the character to get what they need via what they think they want.

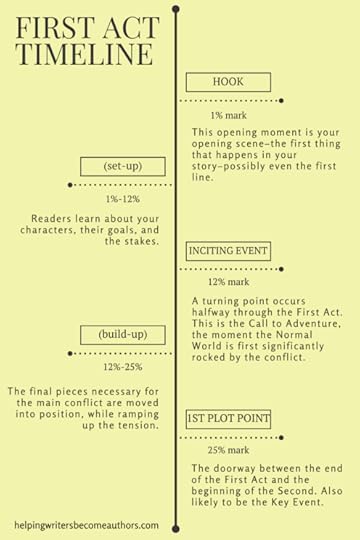

The Structural Job of Your Story’s BeginningFrom a structural perspective, the main function of the beginning is to set up the story that is to follow. Its job is to introduce all of the important elements, whether that’s the characters, the settings, the stakes, the theme, the pieces of your character’s arc (i.e., the Lie the Character Believes, the thematic Truth, the Thing the Character Wants, the Thing the Character Needs). All of that has to be introduced within the First Act. Usually, you will at the very least start foreshadowing almost all of those things from the very first scene in the first chapter.

How can you bring in all these crazy disparate elements that have to start happening within a very confined space? Think about how this first chapter structurally relates to other important structural moments throughout the story.

Using the First Chapter to Set Up the First Plot PointWhat happens in the beginning, whether it’s exactly the first chapter or a little later on, sets up and therefore foreshadows whatever happens at your story’s First Plot Point. The First Plot Point happens around the 25% mark. It’s the the doorway between the First Act and the Second Act. It’s a big moment. It is the moment when your character becomes fully engaged with the story’s main conflict against the antagonistic force in your story. Think about how you can set that up in the very first chapter, even if it’s subtle.

How is what’s happening in this opening scene creating a line of cause and effect within your plot that will lead your character to the First Plot Point? If you realize some of your ideas for this beginning chapter don’t seem to influence the First Plot Point, then it is possible you’re beginning too soon. The true beginning of your story is that moment where the character’s life begins to change. It’s not necessarily dramatic yet; it’s not overt. Very subtly, the circumstances are changing.

The character’s own inner experience is changing in a way that means they cannot remain the way they were anymore. This could be mainly the result of external circumstances. Maybe their neighborhood is going to be condemned, and they have to move, whether they want to or not.

Writing Archetypal Character Arcs (affiliate link)

Or the change could be the result of internal circumstances. This is what we see very often in archetypal character arcs, such as I talk about in my book Writing Archetypal Character Arcs. Wherever you’re at within the life cycle brings you to a point where you’re changing. Puberty is a great example. You don’t get a choice that you’re going on this next character arc into adulthood.

Maybe your character can’t help what’s happening, or maybe they’re excited for it. Maybe they think they know what they’re getting into and they want it. Either way, something is changing. It’s probably subtle. In the first chapter, it’s not at a point where they even recognize their life is going to change forever. But readers get to witness the first rumblings. Those first rumblings are where you want to begin your story. That is what then leads into and foreshadows the First Plot Point at the end of the First Act.

Using the Hook to Set Up the ResolutionOne other thing you can think about structurally, is how the Hook in your story’s beginning mirrors and sets up the Resolution in your story’s ending.

The structural point and job of the first chapter is to act as a hook for readers. It’s to create that opening dynamic that not only kicks off the plot but pulls in readers. The Hook is that first beat in your story’s structure. By the time you get to the Resolution, whatever happens in the beginning, even if it seems very ancillary to the rest of the story, readers should be able to experience a harmony between the beginning and the ending.

For example, perhaps the character returns to wherever they were in the beginning of the story in that first scene. In some stories, this can be an extremely effective way to bring the story full circle and to show how the character and or the world has changed because of the effects of the story.

But the mirroring can be much subtler than that. Sometimes you might literally mirror whatever the Characteristic Moment was in the beginning with another Characteristic Moment in the very end, showing how the character has changed—or maybe they haven’t changed and that’s what you’re trying to emphasize.

Sometimes something you’ve created in the opening scene is something that you can mirror by the time you do get to the ending. Just keep that in mind when writing your story’s beginning. Realize that even if the beginning of the story seems very separate from what’s going to be the main conflict, you can create cohesion and bring the plot full circle by thinking about how any questions (whether overt or subtextual) that you’re raising in that first chapter can eventually be answered in the end.

Again, this can be very subtle. It is probably isn’t something you want readers thinking about throughout the whole story. But you can sow little seeds that can come to fruition at the end. This makes the whole story feel very grounded and resonant and purposeful. Even if you didn’t intend for the foreshadowing and the connections—even if it just magically happens that in the end you’re mirroring something in the beginning—it makes the story seem very intentional.

Techniques for Opening Your Story With a BangThe last couple of things I want to talk about are techniques for opening your story. How can you take these elements we’ve talked about apply them to the actual story? How can you bring these techniques to life in a way that works for readers? It’s one thing for you to say, “This and this and this is going to happen.” It’s another thing to dramatize those events through words in a way readers will enjoy and relate.

Again, the Hook is your primary tool for pulling readers in with all of the great stuff you’re trying to share with them in the story. There are many ways to accomplish this. Bottom line: the Hook is a question. You’re not necessarily necessarily trying to get readers to ask an explicit question, but you do want to pique their curiosity and make them wonder what’s going to happen? with this dynamic.

You want them to ask, “What are the consequences of what just happened?” or “What would make someone do this?”

We’ve talked about backstory in previous video posts and how it can create a whole layer of subtext that makes readers wonder, “Why would someone do this? What’s the motivation?”

Think about how you can sew little hooks that get readers curious. If they’re curious, they keep reading. You can start with a little hook to pull them along until you can start planning bigger and bigger hooks as you continue to develop the main plot.

Opening Your Story In Medias ResNow, one relatively popular way of trying to hook readers and beginning a story is starting in medias res. This is Latin for “in the middle of things.” Very often we see this in action stories where there’s already a battle going on. There’s already a car chase or a battle or whatever, and we are plunged right in the middle of it without knowing what’s going on. We don’t know why these characters are doing this or what’s at stake. It’s just action. The type of action will depend on the context of your story. Maybe it’s relational. For instance, maybe you open right smack in the middle of characters breaking up.

Regardless, the idea is that you’re cutting out the throat-clearing—the explanations of what’s happening—and just getting readers right into the good stuff. This can be very effective, but it’s also quite tricky. Particularly in written fiction, readers need a reason to invest in reading about action. Very often, descriptions of action are quite dense. Action isn’t the easiest thing for readers to immediately jump in and be interested in. Readers need a reason to care about the action. They need to know why your character is running through the streets. Very often, it’s better to hold the action back until at least later in the first chapter, if not later altogether.

Opening Your Story With MovementHowever, the exception is in understanding what it means to open in the middle of the action. You may remember me mentioning in the last video how valuable it can be to open with your character in motion. You want them moving toward something. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re running through the streets or shooting it out or some big action moment. It just means there’s a sense of movement. They’re moving toward something. There’s momentum. There’s a sense they want something—and therefore there’s a plot. There’s a goal, and there’s the opportunity for that goal to be obstructed, which is conflict.

If you can just impart that in your first chapter, that is often enough to allow your story to open in a way that cuts through the throat clearing, gets straight to the point of what the character is doing in this first chapter, without asking readers to invest in a really intense scene where they don’t yet know who they’re sympathizing with or they’re identified with.

Opening Your Story With DialogueVery often opening with dialogue is one of the best ways to begin in the action because dialogue actually is action. I like to say dialogue the purest form of showing rather than telling because, literally, you don’t have to describe it or explain it. It is straight from the horse’s mouth—straight from the character’s mouth. This isn’t to say you want your first line to be dialogue. And you probably do not want a dialogue conversation without the context of dialogue tags that point out who these characters are. But the back and forth of dialogue gives you the opportunity to get readers into the action of the story, while also sewing in bits of information about the characters who are speaking and whatever they’re doing as they go.

Dialogue won’t be appropriate for every story’s first chapter. Obviously, the situation that you’re trying to convey in your first chapter will have a lot to do with deciding whether dialogue is your best opening gambit. But, generally speaking, it is an effective technique for grabbing readers and creating that perfect balance between action and forward momentum, while also giving readers an opportunity to invest in the characters, to understand what’s going on, who’s talking, what they’re doing, what they want, etc.

***

Beginnings have so much ground to cover. There are so many things we could still talk about! Between last month’s video and this one, this a good overview of the basic elements and considerations for crafting a really solid beginning that sets the groundwork for the plot and the whole story to come, while also hooking readers and giving them a reason to be interested in the story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What were your primary plot considerations when beginning your story? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post Checklist for Beginning Your Story: Plot Considerations appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 8, 2024

Writers With ADHD: Strategies for Navigating the Writing Process

Note From KMW: Earlier this year, I received an email from Bret Wieseler, requesting, “I would love to see a post about writers with ADHD. If you’ve never struggled with it yourself, maybe you know someone who has and can share their thoughts, methods, management strategies, etc. You offer such great insight into the many aspects of being a writer. I’m sure some of your readers, like myself, who struggle with ADHD would appreciate any advice you could offer.”

Note From KMW: Earlier this year, I received an email from Bret Wieseler, requesting, “I would love to see a post about writers with ADHD. If you’ve never struggled with it yourself, maybe you know someone who has and can share their thoughts, methods, management strategies, etc. You offer such great insight into the many aspects of being a writer. I’m sure some of your readers, like myself, who struggle with ADHD would appreciate any advice you could offer.”

I immediately knew who to call on, and I am excited to share a guest post today from a writer who has been a part of my own journey almost from the very beginning. Johne Cook and I met on an online writing forum over 15 years ago, and he remains one of my favorite people to have entered my life in this journey. I have long admired his pragmatism, his insight, and his general cool in the face of the Internet’s insanity. To this day, I will often ask myself, “What would Johne do here?”

He has always been open about his experience as a writer with ADHD—both the challenges and his solutions for overcoming them. Today, I’m excited to have the opportunity to let him share his experience, tips, and resources with you. Enjoy this treasure trove of insight!

***

DiscoveryI wish I knew then what I know now.

For my first 45 years, I thought I was broken: I was a daydreamer, I couldn’t focus on things everyone else thought were important, I fidgeted when I should have been focusing, and I focused intently on the wrong things when people wanted my attention elsewhere.

It’s not like there weren’t clues. I excelled as part of an award-winning marching band in high school where marching in unison was expected, but it was like I was out of step with society.

I had difficulties with organization, time management, and sustaining attention in non-stimulating environments.

I couldn’t make important decisions to save my life. I kept putting things off. I had health problems, money problems, interpersonal problems.

I waited until the 11th hour to begin anything important, and things frequently fell through the cracks.

When I was young, what I wanted most was to be “normal.” But the older I got, the more I believed that was never my reality or calling.

Everything changed the day I heard a piece on NPR called “Adult ADHD in the Workplace.” As they discussed what ADHD was and shared six basic questions, I realized I checked five of the six boxes. They shared a link to a website, and I double-checked my results when I got home.

And then I met with a doctor and confirmed the diagnosis. My entire identity changed.

When I tried two different medications that gave me additional focus at the expense of my creativity (and some other small side effects), I sensed, for the first time, that my creativity was somehow tied to my condition. I valued my ability to sling words, see patterns, and make intuitive leaps that others around me couldn’t.

Because I valued my creativity, I ultimately handled my ADHD through other means that I’ll talk about below.

I realized I could either run from my ADHD or embrace it.

I decided to lean into it.

CommunicationKnowing is half the battle. Knowing this about myself (and knowing that I was special, not broken) changed the way I saw everything.

I started by talking to my wife Linda and my family about what I was like and gradually increased my communication to include my boss and peers at work.

For some of them, what I told them was no surprise, and my biggest pleasant shock was how cool everyone was about it.

Finally, when appropriate, I shared about my ADHD with people I met out in the world. Letting people know what I was like set expectations and minimized confusion.

Once I had that handled, I moved on to the fun stuff.

ADHD as a SuperpowerIf attention deficit is the disorder, attention hyper-focus is my superpower.*

During the pandemic, Linda and I watched an interrupted season of The Amazing Race, mostly for Penn and Kim Holderness from YouTube’s The Holderness Family. It was only while watching the show that we learned that Penn was very ADHD. They referred to his ADHD as a superpower, and I saw with my own eyes how his ADHD helped him with pattern recognition, creative outside-the-box thinking, and hyper-focus during challenges.

And watching Penn at work on the show changed how I viewed my own ADHD.

In short, when managed effectively and embraced for its positive attributes, ADHD can empower writers to harness their inner strengths and achieve success in various domains of life.

Understanding ADHD in the Writing ProcessPeople with ADHD exhibit different symptoms such as difficulty maintaining attention, hyperactivity, or impulsive behavior. For writers, these symptoms can manifest as challenges in organizing thoughts, staying on task, and completing projects.

However, it’s also associated with high levels of creativity, the ability to make unique connections, and a propensity for innovative thinking.

Challenges Faced by Writers With ADHD(The following challenges are common but not universal.)

Distraction: Writing progress can be derailed by the lure of new ideas, social media, or even minor environmental changes.Difficulty Organizing Thoughts: It can be daunting to translate a whirlwind of thoughts into coherent, structured writing.Procrastination: Delaying writing tasks in favor of more immediately rewarding activities.Impulsivity: Starting new projects without finishing current ones can lead to a cycle of uncompleted works.Despite these challenges, many writers with ADHD have developed strategies to thrive.

Strategies and Tools for Writing with ADHDI decided against medication. Once I took medication off the table, I began leaning harder on software tools to become more organized and to remind myself of important things.

Turning ADHD challenges into advantages requires a combination of personal strategies, environmental adjustments, and technology.

Linda and I are a team—she knows to prompt me to use my tech to capture ideas or thoughts in the moment, and I’ve become better at tracking my ideas by noting them in my phone or on my calendar.

Today, there are more tools available than ever.

Here are several approaches:

1. Structuring the Writing EnvironmentMinimize Distractions: Create a writing space with minimal visual and auditory distractions. Tools like noise-canceling headphones or apps that play white noise can help.

Establish Routines: Having a set writing schedule can provide structure and make it easier to start writing sessions.

2. Breaking Down Tasks

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Use Lists and Outlines: Breaking writing projects into smaller, manageable tasks can make them less daunting. Outlining can also help organize thoughts before diving into writing.

Set Small Goals: Focus on short, achievable objectives, such as writing a certain number of words daily, to build momentum.

3. Leveraging TechnologyCalendars: Google Calendar or Fantastical (MacOS only) free up my mind and keep me up-to-date.

Writing Software: Applications like Scrivener or Google Docs offer features to organize ideas, research, and drafts in one place.

Time Management Apps: Pomodoro timers or task management apps like Trello can help manage time and keep track of progress.

Pocket: A social bookmarking service for storing, sharing, and discovering web bookmarks.

SnagIt: A screenshot app on my computer where I capture and store screenshots in folders for later use. Also does optical character recognition (OCR) on text strings, allowing me to replicate URLs with copy/paste.

Note-taking apps: Apple Notes—my second mind that I can access from any of my Internet-connected devices. Notion—a beefier app for more sophisticated note-taking

4. Embracing the Creative ProcessAllow for Free Writing: Set aside time to write without worrying about coherence or structure. This can help capture creative ideas without the pressure of perfection.

Develop a System for Capturing Ideas: Use note-taking apps or carry a notebook to jot down ideas as they come, regardless of the time and place.

5. Seeking SupportWriting Groups: Joining a writing group or participating in writing challenges can provide accountability and motivation.

Professional Help: For some, working with a coach or therapist specializing in ADHD can offer personalized strategies and support.

Success Stories: Writers With ADHDMany successful writers have ADHD and have spoken about how it affects their creative process. Writers emphasize the importance of embracing their non-linear thinking, and view it not as a hindrance, but as a source of creativity and originality:

Agatha Christie: The “Queen of Crime” was known for her prolific output and intricate plots. Some speculate that her energetic writing style and ability to focus intensely on details could be signs of ADHD.

Murder at the Vicarage by Agatha Christie (affiliate link)

Dav Pilkey: The creator of the popular children’s book series Captain Underpants has openly discussed his struggles with ADHD. He credits his condition with helping him be a creative thinker.

The Adventures of Captain Underpants by Dav Pilkey (affiliate link)

John Irving: The author of The World According to Garp was diagnosed with ADHD as an adult and has spoken about how his condition has both helped and hindered his writing process.

The World According to Garp by John Irving (affiliate link)

ConclusionAs a writer, I don’t see things the way others do. I think outside the box.

My ADHD makes me more:

CreativeEnergeticInnovativeHyper-focused on things that capture my attentionDon’t let anyone tell you ADHD is a curse. You can view it as a gift. You can embrace it.

And then you, too, can lean into it!

Resources and Further ReadingFor those looking to dive deeper into managing ADHD as a writer, or seeking inspiration from those who’ve navigated similar challenges, here are some invaluable resources:

ADHD Questionnaire (a questionnaire based on an internationally respected screening tool for ADHD) 6 Surprising Ways My ADHD Brain Helped Me Write an Award-Winning Novel The Link Between Creativity and ADHD Tool & Tricks For Writers With ADHD ADHD Is Awesome written and read by Penn and Kim Holderness* Hyperfocus is common but not universal.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Can you share any tips or experiences for managing ADHD as a writer? Tell us in the comments!The post Writers With ADHD: Strategies for Navigating the Writing Process appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

April 1, 2024

How to Choose Story Settings: The 4 Basic Types of Setting

Beyond mere backdrop, story settings are what allow authors to orchestrate meaningful connections among characters. Settings should serve as more than just scenery. They should provide characters with compelling reasons to share the stage with one another. Accomplishing this in a story requires understanding how to strategically choose story settings as meeting grounds that amplify character interactions and deepen the resonance of the narrative.

Beyond mere backdrop, story settings are what allow authors to orchestrate meaningful connections among characters. Settings should serve as more than just scenery. They should provide characters with compelling reasons to share the stage with one another. Accomplishing this in a story requires understanding how to strategically choose story settings as meeting grounds that amplify character interactions and deepen the resonance of the narrative.

When writers choose story settings, they don’t always think about why they are choosing specific settings. You might choose a particular setting for a number of reasons:

It seems like the most obvious or convenient choice to facilitate a scene’s plot events (e.g., a diner as a place to meet locals).It’s an interesting or unique locale that seems fun to explore (e.g., a space station).It seems symbolically resonant to the scene’s thematic content (e.g., a graveyard).Sometimes settings come pre-packaged with certain genres (e.g., expansive worlds in fantasy or the halls of Congress or the White House in political dramas) or certain tropes (e.g., high schools in YA romances or famous world landmarks in international spy thrillers). Sometimes the setting will be the entire point of the premise (e.g., a burning skyscraper in The Towering Inferno or a Russian sub in The Hunt for Red October). Other times, settings are retrofitted into a story based on the needs of the plot (e.g., a claustrophobic setting is required for a climactic encounter between protagonist and antagonist).

The Hunt for Red October (1990), Paramount Pictures.

Although these are legitimate factors, none get at the heart of one of the most important metrics for how to choose story settings. That metric is simply: figuring out which settings will facilitate plot events that keep readers riveted.

At first glance, authors might be tempted to think the best way to rivet readers with setting is simply to choose something flashy and unique. But here’s the thing: flashy and unique settings won’t matter to readers at all if those same settings don’t give them what they’re really here for. And what is that? Simply, they came for the story. They came for the characters and for how those characters act when put in certain situations (aka, the plot).

But, again, let’s drill deeper. After all, you can have characters doing all kinds of plot stuff on the page—running around in exciting settings, exploring, seeing new things, shooting it out with the bad guy, falling in love, all of it—and still not satisfy readers. Story (as opposed to a string of scenes) is a development of character. Setting needs to facilitate that—either by becoming a catalytic “character in its own right” or by creating situations that bring other characters together.

In short, one of the key considerations for how to choose story settings is whether these settings will promote important dynamics between characters.

The General Rule of Thumb for How to Choose Story SettingsUltimately, my top metric for how to choose story settings is simply logistics. Every time you maneuver characters into a setting, you need to ask how it will affect their proximity to other important characters. Closer isn’t always better (as we’ll explore in the next section), but generally speaking, if your most interesting characters are not sharing space for most of the story, you are wasting serious entertainment opportunities.

I have read and watched so many stories that were legitimately great in all other respects, but which failed to entertain, sometimes for chapters or episodes on end, because the author’s choice to separate characters into different settings killed the chemistry and all the good stuff that goes with it. This includes opportunities for dialogue, relational conflict, and the integral plot development created by the mutuality of characters’ cause and effect upon one another.

This post was inspired after I started the second season of Amazon’s steampunk fantasy Carnival Row. Although it struggled a bit after the antag reveal toward the end, Season 1 was a delight—a rare fantasy show that not only developed a unique and cohesive world but kept its plot tightly focused on its primary characters. In it, the primary setting of the Dickensian slum Carnival Row creates a milieu that keeps crossing the paths of ill-fated lovers Philo, a human detective, and Vignette, a “pix” freedom fighter and refugee. Not only does this setup allow the characters’ individual plotlines to become more and more intertwined, it also ensures that the bulk of their scenes offer viewers juicy interpersonal conflict and development—which, in turn, translates to higher stakes in the exterior plot.

Carnival Row (2019-23), Amazon Studios.

Season 2, unfortunately, immediately compromised itself by separating its two main characters. Although they now live together, the plot is engineered to put the characters in separate settings from the beginning. This was clearly designed with the idea that the next phase of the characters’ interpersonal development would be confronting their opposing goals and methods for saving Carnival Row. On its surface, this does not seem like a bad plan for the plot. But the practical outcome is that the primary dynamic that worked so well in the first season is utterly upended in the second. As a result, the relationship simply isn’t as interesting as it was in the first season. Thus the stakes aren’t as engaging, the individual plotlines fall comparatively flat, and the supporting characters who are amped up to try to remedy this can’t save the show.

Carnival Row (2019-23), Amazon Studios.

When choosing settings (and plot events, for that matter), it is so important to look beyond the top layer of what seems eye-catching or obvious. Instead, dig down to the actual effect these choices will have on the entire story. Are you choosing settings that bring your characters together—or that force them apart? Are you choosing settings that create and enhance your story’s most entertaining dynamics—or settings that generate scenes readers may, in fact, end up skimming or skipping?

We don’t always think of setting when questioning these aspects of our stories, but we should. Setting can offer tremendous clues into how the story may or may not be developing its tightest and most engaging possibilities.

The Logistics of How to Choose Story SettingsReally, all you need to know about how to choose story settings that enhance your plot’s possibilities is that you want settings that create the cauldron into which all of your story’s best individual elements can be alchemized into an intriguing whole.

To go deeper with this, explore the underlying purpose of any setting in your story. On the surface, the purpose of a setting might seem to be something along the lines of “where the first murder victim is discovered” or “where the protagonist finds the shocking letter from her dead ex” or “the gas station where the characters are robbed.” Deeper down, each of these scenarios creates a specific impact upon the characters and the evolution of their respective positioning in the story related to all other characters. These logistics create dynamics, and dynamics create gripping fiction.

Today, let’s examine four types of setting. It’s interesting (although certainly not necessary) to recognize that each of these setting types is, in fact, inherent to the four sections of story structure (as represented by the Normal World, the Adventure World, the Underworld, and the New Normal World). This doesn’t mean each of the following setting types needs to be used in order or exclusively in alignment with the four sections of story structure. Indeed, you will probably mix and match multiple iterations of these setting types throughout your story. But recognizing the association of these primary archetypes with the larger pattern of story can further underline how each one functions within the mechanics of your plot.

1. Settings That Are Meeting GroundsAny setting that falls into this category is a powerhouse of opportunity for your story. Meeting Grounds are settings designed to bring characters together. This may be for an initial meeting, but it can also create a dynamic that brings characters together over and over again, allowing the relationship to evolve and develop with each new meeting.

The more Meeting Ground settings you incorporate into your story (or the more use you’re able to make of a single Meeting Ground), the more opportunity your story will have for scenes in which interesting characters are forced to come together. Meeting Grounds offer an inherent sense of movement. They are not static spaces, in which characters rest together, but spaces in which they are always coming and going.

Job places are an obvious example, as are schools, in which characters have no choice but to see each other every day. Other types of Meeting Places can be restaurants or bars.

For Example: Casablanca‘s entire setting is one big Meeting Ground, built around a plot in which characters use Casablanca in general and Rick’s Café in particular as a stopping-off point in an attempt to escape war-torn Europe and Africa. This then allows a specific premise in which protagonist Rick is forced to reunite with his lost love Ilsa, who is desperate to escape with her freedom-fighter husband.

Casablanca (1942), Warner Bros.

*Meeting Ground symbolically aligns with the Normal World‘s function of the First Act.

2. Settings That Are Shared SpaceShared Spaces are those in which characters expect to be together. They may or may not want to be in this space, but they are there because it is mutually beneficial. Shared Spaces are designed to give you the opportunity to keep characters together long enough to develop their interpersonal conflict apart from any bigger external conflict.

Shared Spaces are not so energetically dynamic and changeable as Meeting Grounds, but they offer the opportunity to go deep. They are often appropriate for the “sequel” half of scene structure, which focuses on character reactions. This type of setting may be employed when you want to signify comparative peace within a relationship dynamic. The characters will have the opportunity to come together and learn more about each other, which deepens their bond and raises the stakes.

At its most positive, a Shared Space might be a home cohabited by multiple characters, someplace safe and inviting, where everyone enjoys being together. More negatively, a Shared Space might be a place of refuge, where disparate characters huddle together out of no other commonality than that of trauma and survival.

For Example: In The Hunger Games: Catching Fire and Mockingjay, protagonist Katniss finds herself sharing space with other Panem refugees, including her mother and sister, in the rundown District 13. This setting creates the opportunity to develop characters and relationships that create the stakes for the external action that happens later in the arena.

The Hunger Games: Mockingjay, Part 1 (2014), Lionsgate.

*Shared Space symbolically aligns with the “friends and allies” aspect of the Adventure World of the Second Act.

3. Settings That Are Shared DangerEqually interesting and important are settings of Shared Danger. Scenes of Shared Danger create the framework for your heavy-lifting plot scenes, those that move the story forward in the external conflict. Shared Danger needn’t always be physical or dire. It simply represents situations in which characters must turn outward to face external threats.

Characters who share these spaces may be either allies or enemies—either protecting each other from external danger or creating the danger for one another. The important distinction here is that the danger is “shared.” This ensures external plot events are (usually) occurring in a way that creates interpersonal stakes and conflict amongst characters.

Conflict and “danger” can be introduced into almost any type of setting. A home invasion would quickly transform a Shared Space setting into one of Shared Danger. However, it is also possible to engineer specific settings within your story that are designed to enhance conflict by choreographing characters into a space that is either dangerous in its own right or made more so by the presence of antagonistic forces.

War zones, “disaster” settings (such as burning buildings and sinking ships), wilderness settings, and confined or cluttered settings can all be used to enhance physical danger. In less physical stories, settings that emphasize Shared Danger could be tension-filled workspaces or homes filled with difficult family members.

For Example: An archetypal example is the prison in Shawshank Redemption, which traps the protagonist and many others in a hellscape populated by manifold dangers.

Shawshank Redemption (1994), Columbia Pictures.

A more prosaic example would be the Westons’ family home in August: Osage County, where the three grown daughters must endure a reunion with their toxic and volatile mother.

August: Osage County (2013), The Weinstein Company.

*Shared Danger symbolically aligns with the Underworld aspect of the Third Act.

4. Settings That Are a Parting of the WaysSettings that facilitate a Parting of the Ways should be used with caution. On the one hand, they afford the opportunity for deeply complex and poignant scenes, as characters must at least temporarily dissolve the dynamic they have created amongst themselves. However, because these settings also eventuate plots in which interesting relational dynamics are eliminated from the story, they can negatively affect the reading experience unless utilized with understanding and caution.

Parting of the Ways settings are the opposite of Meeting Grounds; they are settings that divide characters from one another. Any type of setting can be utilized to create this effect. Often, the best Parting of the Ways setting for a particular story will be one that offers symbolic and personal import to the characters. More obviously, airports and train stations often function to separate characters from one another.

Parting of the Ways settings may be introduced into a story in one of two ways. The first is that the author deliberately chooses a setting and its inherent scenario to separate characters for plot reasons, The second is that the author incidentally chooses a Parting of the Ways setting that separates the characters for reasons not required by the plot—and then drags readers through unnecessary scenes in which the parting must be played out to satisfy cause and effect.

Although an author can legitimately choose to separate characters for reasons that don’t, in fact, advance the story, this scenario is the one authors must be especially careful of when choosing settings. If any particular setting or plot circumstance creates separation between characters who have an interesting or important relationship dynamic, always step back and ask yourself if this is truly serving the plot and the character development.

For Example: In The Fellowship of the Ring, the Breaking of the Fellowship at Amon Hen is where Frodo and Sam leave the others. This effectively splits the story, advancing three different plotlines from this point on. This is undeniably important for the overall scope of the story. However, the main reason it actually works is because the primary relationship dynamics are preserved—Frodo and Sam remain a unit; Pippin and Merry remain a unit; and Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli remain a unit.

The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001), New Line Cinema.

A generic negative example is one found in countless other fantasy war stories, in which friends are separated to fight on different fronts. This is usually done for no other reason than to give the author an excuse to explore different facets of the story. If it destroys the story’s central relationship dynamic—and especially if it does not replace it with an equally meaningful relationship—it is never worth the expanded plot opportunities.

*Parting of the Ways symbolically aligns with the New Normal World of the Resolution.

***

Writers often select settings based on convenience, novelty, or thematic resonance, but the true measure of a setting’s effectiveness lies in its ability to enhance the dynamics between characters. Examining these four setting types—Meeting Grounds, Shared Spaces, Shared Danger, and Parting of the Ways—shows the nuanced role each plays in shaping character relationships. The strategic selection of story settings hinges on crafting a narrative crucible where every element harmoniously blends and readers are always given more, rather than less, of what is best about your story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What do you think is the most important consideration in how to choose story settings? Tell me in the comments!Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)The post How to Choose Story Settings: The 4 Basic Types of Setting appeared first on Helping Writers Become Authors.

March 25, 2024

From Lead to Gold: The Alchemy of Character Arc With Carl Jung

Storytelling is a mystical crucible. Just as the ancient alchemists sought the transformation of base metals into gold, writers strive for the metamorphosis of their characters’ inner selves throughout the story. Alchemy, as explored through the lens of Carl Jung’s insights, can elevate your characters from the leaden weight of initial flaws to the gleaming brilliance of transformation.

Storytelling is a mystical crucible. Just as the ancient alchemists sought the transformation of base metals into gold, writers strive for the metamorphosis of their characters’ inner selves throughout the story. Alchemy, as explored through the lens of Carl Jung’s insights, can elevate your characters from the leaden weight of initial flaws to the gleaming brilliance of transformation.

Last fall, I spent part of my month-long writing retreat in the Berkshires auditing a series of online lectures from the Centre of Applied Jungian Studies. These lectures from leading Jungian experts, collected under the heading “The Mystery School,” explored revolutionary depth psychologist C.G. Jung’s writings and theories about how ancient alchemy stands as a metaphor for psychological transformation. Throughout, my excitement grew as I recognized that the four intrinsic parts of the alchemical/analytical process are also reflected in (surprise!) story structure.

Some of you may remember I posted about this Instagram.

View this post on Instagram

A post shared by KM Weiland (@authorkmweiland)

So what is alchemy, and why should writers care? For me, one of the most delightful mysteries of life is how, when you start paying attention, the theories of story structure and character arc show up everywhere. Not only is this interesting in applying the wisdom of story to life, it also creates opportunities to learn how to tell better stories by examining systems that, at first glance, seem to have nothing to do with fiction.

The series of lectures I watched focused on Jung’s recognition that the four parts of alchemy naturally aligned with his own four tenets of analysis and personal transformation. Even though I teach a Three Act structure, this structure divides story into four equal parts. Particularly when examined from the perspective of character arc, these four parts align naturally and perfectly with the four parts of alchemy/Jungian analysis. The pattern deepens!

I’ve written before about how writers can apply various theoretical models (such as the Karpman Drama Triangle and the Enneagram) to storytelling. Alchemy is yet another window through which to view story. It offers a tool to help us shape our stories into greater verisimilitude. Plus, if you’re a pattern hunter, as I am, it’s just cool!

Today, I invite you to explore the parallels in these systems and to glean new insights into how to craft psychologically resonant stories. I’m just beginning to scratch the surface of this comparison myself and can’t wait to share more about it in the future. For now, here are some of the parallels.

The Four Stages of Alchemy

The Alchemist by Paulo Coelho (affiliate link)

Apart from Paulo Coelho’s beautiful fable The Alchemist, most of us probably aren’t super-familiar with the ancient ideas of alchemy. Put simply, the alchemists believed they could discover a scientific method for turning lead into gold. Great tomes were written about their experiments, although there was never any evidence of success (until modern science).

As time went on, Jung and others began to posit that alchemy was really a metaphor for psychological transformation in which the lead of the self may be refined into a higher state of “gold.” In later life, Jung studied and theorized extensively about how the principles of alchemy could be utilized as archetypal wisdom for furthering the analytic process.

Although alchemy can be broken down into further stages, the four main ones are as follows:

1. The Nigredo: The BlackeningIn functional alchemy, this represented the burning away of the initial base dross. The goal was to remove all impurities in a return to the “prima materia” (the original pure) and to emerge with the golden Philosopher’s Stone.

Psychologically, the Nigredo represents the beginning of transformation. It is the Dark Night of the Soul, the death that creates the opportunity for rebirth. It is a period of recognizing and facing one’s shadow as the first step toward integration and wholeness. (And for more on the shadow, check out my brand new email course Shadow Archetypes: Writing Complex Fictional Characters!)

2. The Albedo: The WhiteningThe second step is that of further purification, as the alchemist takes steps to wash away impurities after the Nigredo phase and/or shine a light upon the work to highlight further impurities. Here, the lead becomes silver.

Psychologically, the Albedo represents the beginning of individuation. The period is marked by a recognition of two separate entities that emerged during the confrontation with the shadow in the previous stage and which now invite a movement toward union.

3. The Citrinitas: The YellowingThe third step signifies the appearance of a yellow or gold color. This stage is often associated with the idea of the sun rising, symbolizing the infusion of warmth and light into the alchemical work.

Psychologically, Citrinatus can be interpreted as the emergence of enlightenment, spiritual insight, or a higher state of consciousness. It suggests a progression toward the culmination of the alchemical journey, where the transformative process takes on a radiant and luminous quality.

4. The Rubedo: The ReddeningThe final step represents the culmination of the Great Work, or Magnum Opus. Rubedo is characterized by the appearance of a vibrant red or gold color, symbolizing the attainment of perfection (i.e., the Philosopher’s Stone). This stage is associated with the union of opposites, the integration of purified elements, and the realization of spiritual rebirth. The alchemist, having undergone the challenges of the preceding stages, achieves the highest level of transformation and transmutation.

The Rubedo is a symbol of the soul’s journey toward self-realization and the ultimate goal of alchemy: the reunion and reintegration of soul and psyche into a unified whole.

The Four Stages of Jungian AnalysisAmongst Carl Jung’s mountainous legacy of work, his application of alchemical symbolism to his own systems of psychological analysis and transformation are among the most intriguing. Earlier, he developed a four-part approach to what he called analytical psychology, which he describes in the Collected Works of C.G. Jung, Vol. 16:

Analytical psychology is defined as embracing both psychoanalysis and individual psychology. This approach includes four stages: confession, elucidation, education and transformation.