Cheryl B. Klein's Blog, page 10

August 26, 2012

The Quote File: Ideas

“I begin with an idea and then it becomes something else.” — Picasso

"If you want to find, you must search. Rarely does a good idea interrupt you." — Jim Rohn

"You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it." — Neil Gaiman

"The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas." — Linus Pauling

"If you are seeking creative ideas, go out walking. Angels whisper to a man when he goes for a walk." — Raymond Inman

“Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.” — John Steinbeck

“That’s the great secret of creativity. You treat ideas like cats: you make them follow you.” — Ray Bradbury

"The question authors get asked more than any other is "Where do you get your ideas from?" And we all find a way of answering which we hope isn't arrogant or discouraging. What I usually say is ‘I don't know where they come from, but I know where they come to: they come to my desk, and if I'm not there, they go away again.’” — Philip Pullman

“Creative ideas flourish best in a shop which preserves some spirit of fun. Nobody is in business for fun, but that does not mean there cannot be fun in business.” — Leo Burnett

“First drafts are for learning what your novel or story is about. Revision is working with that knowledge to enlarge and enhance an idea, to re-form it.... The first draft of a book is the most uncertain—where you need guts, the ability to accept the imperfect until it is better.” —Bernard Malamud

“To get the right word in the right place is a rare achievement. To condense the diffused light of a page of thought into the luminous flash of a single sentence, is worthy to rank as a prize composition just by itself....Anybody can have ideas--the difficulty is to express them without squandering a quire of paper on an idea that ought to be reduced to one glittering paragraph.” — Mark Twain

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” — Henry Ward Beecher

“A book is the only place in which you can examine a fragile thought without breaking it, or explore an explosive idea without fear it will go off in your face. It is one of the few havens remaining where a mind can get both provocation and privacy.” — Edward P. Morgan

"An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all." — Oscar Wilde

“Every man is a creature of the age in which he lives, and few are able to raise themselves above the ideas of the time.” —Voltaire

“When we want to infuse new ideas, to modify or better the habits and customs of a people, to breathe new vigor into its national traits, we must use the children as our vehicle; for little can be accomplished with adults.” — Maria Montessori

“We have a powerful potential in our youth, and we must have the courage to change old ideas and practices so that we may direct their power toward good ends.” — Mary McLeod Bethune

“Cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation or social standards never can bring about reform. Those who are really in earnest are willing to be anything or nothing in the world's estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathies with despised ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences.” — Susan B. Anthony

“Our heritage and ideals, our code and standards — the things we live by and teach our children — are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange ideas and feelings.” — Walt Disney

“We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.” — John F. Kennedy

“Oh, would that my mind could let fall its dead ideas, as the tree does its withered leaves!” —Andre Gide

“A fixed idea is like the iron rod which sculptors put in their statues. It impales and sustains.” — Hippolyte Taine

“Apologists for a religion often point to the shift that goes on in scientific ideas and materials as evidence of the unreliability of science as a mode of knowledge. They often seem peculiarly elated by the great, almost revolutionary, change in fundamental physical conceptions that has taken place in science during the present generation. Even if the alleged unreliability were as great as they assume (or even greater), the question would remain: Have we any other recourse for knowledge? But in fact they miss the point. Science is not constituted by any particular body of subject matter. It is constituted by a method, a method of changing beliefs by means of tested inquiry.... Scientific method is adverse not only to dogma but to doctrine as well.... The scientific-religious conflict ultimately is a conflict between allegiance to this method and allegiance to even an irreducible minimum of belief so fixed in advance that it can never be modified.” — John Dewey

“A belief is not an idea held by the mind, it is an idea that holds the mind.” — Elly Roselle

“To die for an idea; it is unquestionably noble. But how much nobler it would be if men died for ideas that were true.” — H.L. Mencken

“The man who strikes first admits that his ideas have given out.” — Chinese proverb

“We should have a great many fewer disputes in the world if words were taken for what they are, the signs of our ideas, and not for things themselves.” — John Locke

"Ideas are far more powerful than guns. We don't allow our enemies to have guns, why should we allow them to have ideas?" — Joseph Stalin

"Beware of people carrying ideas. Beware of ideas carrying people." — Barbara Harrison

“What matters is not the idea a man holds, but the depth at which he holds it.” — Ezra Pound

“The only force that can overcome an idea and a faith is another and better idea and faith, positively and fearlessly upheld.” — Dorothy Thompson

"If you want to find, you must search. Rarely does a good idea interrupt you." — Jim Rohn

"You get ideas from daydreaming. You get ideas from being bored. You get ideas all the time. The only difference between writers and other people is we notice when we’re doing it." — Neil Gaiman

"The best way to have a good idea is to have a lot of ideas." — Linus Pauling

"If you are seeking creative ideas, go out walking. Angels whisper to a man when he goes for a walk." — Raymond Inman

“Ideas are like rabbits. You get a couple and learn how to handle them, and pretty soon you have a dozen.” — John Steinbeck

“That’s the great secret of creativity. You treat ideas like cats: you make them follow you.” — Ray Bradbury

"The question authors get asked more than any other is "Where do you get your ideas from?" And we all find a way of answering which we hope isn't arrogant or discouraging. What I usually say is ‘I don't know where they come from, but I know where they come to: they come to my desk, and if I'm not there, they go away again.’” — Philip Pullman

“Creative ideas flourish best in a shop which preserves some spirit of fun. Nobody is in business for fun, but that does not mean there cannot be fun in business.” — Leo Burnett

“First drafts are for learning what your novel or story is about. Revision is working with that knowledge to enlarge and enhance an idea, to re-form it.... The first draft of a book is the most uncertain—where you need guts, the ability to accept the imperfect until it is better.” —Bernard Malamud

“To get the right word in the right place is a rare achievement. To condense the diffused light of a page of thought into the luminous flash of a single sentence, is worthy to rank as a prize composition just by itself....Anybody can have ideas--the difficulty is to express them without squandering a quire of paper on an idea that ought to be reduced to one glittering paragraph.” — Mark Twain

“All words are pegs to hang ideas on.” — Henry Ward Beecher

“A book is the only place in which you can examine a fragile thought without breaking it, or explore an explosive idea without fear it will go off in your face. It is one of the few havens remaining where a mind can get both provocation and privacy.” — Edward P. Morgan

"An idea that is not dangerous is unworthy of being called an idea at all." — Oscar Wilde

“Every man is a creature of the age in which he lives, and few are able to raise themselves above the ideas of the time.” —Voltaire

“When we want to infuse new ideas, to modify or better the habits and customs of a people, to breathe new vigor into its national traits, we must use the children as our vehicle; for little can be accomplished with adults.” — Maria Montessori

“We have a powerful potential in our youth, and we must have the courage to change old ideas and practices so that we may direct their power toward good ends.” — Mary McLeod Bethune

“Cautious, careful people always casting about to preserve their reputation or social standards never can bring about reform. Those who are really in earnest are willing to be anything or nothing in the world's estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathies with despised ideas and their advocates, and bear the consequences.” — Susan B. Anthony

“Our heritage and ideals, our code and standards — the things we live by and teach our children — are preserved or diminished by how freely we exchange ideas and feelings.” — Walt Disney

“We are not afraid to entrust the American people with unpleasant facts, foreign ideas, alien philosophies, and competitive values. For a nation that is afraid to let its people judge the truth and falsehood in an open market is a nation that is afraid of its people.” — John F. Kennedy

“Oh, would that my mind could let fall its dead ideas, as the tree does its withered leaves!” —Andre Gide

“A fixed idea is like the iron rod which sculptors put in their statues. It impales and sustains.” — Hippolyte Taine

“Apologists for a religion often point to the shift that goes on in scientific ideas and materials as evidence of the unreliability of science as a mode of knowledge. They often seem peculiarly elated by the great, almost revolutionary, change in fundamental physical conceptions that has taken place in science during the present generation. Even if the alleged unreliability were as great as they assume (or even greater), the question would remain: Have we any other recourse for knowledge? But in fact they miss the point. Science is not constituted by any particular body of subject matter. It is constituted by a method, a method of changing beliefs by means of tested inquiry.... Scientific method is adverse not only to dogma but to doctrine as well.... The scientific-religious conflict ultimately is a conflict between allegiance to this method and allegiance to even an irreducible minimum of belief so fixed in advance that it can never be modified.” — John Dewey

“A belief is not an idea held by the mind, it is an idea that holds the mind.” — Elly Roselle

“To die for an idea; it is unquestionably noble. But how much nobler it would be if men died for ideas that were true.” — H.L. Mencken

“The man who strikes first admits that his ideas have given out.” — Chinese proverb

“We should have a great many fewer disputes in the world if words were taken for what they are, the signs of our ideas, and not for things themselves.” — John Locke

"Ideas are far more powerful than guns. We don't allow our enemies to have guns, why should we allow them to have ideas?" — Joseph Stalin

"Beware of people carrying ideas. Beware of ideas carrying people." — Barbara Harrison

“What matters is not the idea a man holds, but the depth at which he holds it.” — Ezra Pound

“The only force that can overcome an idea and a faith is another and better idea and faith, positively and fearlessly upheld.” — Dorothy Thompson

Published on August 26, 2012 20:48

August 25, 2012

"Throwing Away the Alarm Clock" by Charles Bukowski

via The Writer's Almanac

my father always said, "early to bed and

early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy

and wise."

it was lights out at 8 p.m. in our house

and we were up at dawn to the smell of

coffee, frying bacon and scrambled

eggs.

my father followed this general routine

for a lifetime and died young, broke,

and, I think, not too

wise.

taking note, I rejected his advice and it

became, for me, late to bed and late

to rise.

now, I'm not saying that I've conquered

the world but I've avoided

numberless early traffic jams, bypassed some

common pitfalls

and have met some strange, wonderful

people

one of whom

was

myself—someone my father

never

knew.

my father always said, "early to bed and

early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy

and wise."

it was lights out at 8 p.m. in our house

and we were up at dawn to the smell of

coffee, frying bacon and scrambled

eggs.

my father followed this general routine

for a lifetime and died young, broke,

and, I think, not too

wise.

taking note, I rejected his advice and it

became, for me, late to bed and late

to rise.

now, I'm not saying that I've conquered

the world but I've avoided

numberless early traffic jams, bypassed some

common pitfalls

and have met some strange, wonderful

people

one of whom

was

myself—someone my father

never

knew.

Published on August 25, 2012 08:34

August 24, 2012

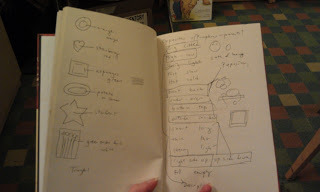

The Editorial Life: My Working Notebooks

When I started working as Arthur's editorial assistant back in 2000, I quickly discovered that I had a lot to keep track of: his appointments and any materials he might need to prep for them, my personal to-do list, people who called, what Production needed from us each day, what manuscripts most urgently required a response . . . a long, long list of priorities to juggle and information to track. There was only one possible solution to contain all this: a notebook! And as soon as I got one, my work life got a hundred times more organized.

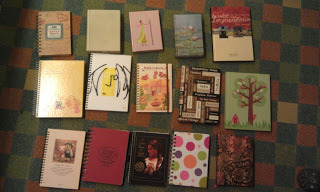

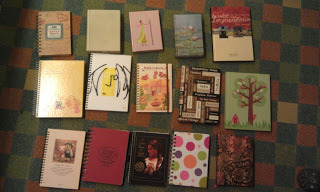

Here are my collected notebooks from 2001 through today:

I keep them because I never know when I might need to make contact with someone I spoke to on the phone about a project in April 2006 -- and I really have used these for information like that! I have also become very particular about the qualities of my notebooks through the years. A good working notebook has to open flat. Either a wire binding or a standard glued binding can work, but glued is slightly preferable, as then the wire doesn't dig into my hand when I write on the left-hand page. The notebook indeed has to be wide enough to hold my whole hand as I write, and/or have few enough pages that my wrist is still supported on the desk. And I like lined paper, but with the lines a decent distance apart, so my handwriting doesn't have to be any more crabbed than it already is when I write quickly. I don't know if many other editors use them -- any editorial readers: Do you? -- but I do give notebooks like this to new editorial assistants, to provide a home for all the many notes they have to take on procedures, and to welcome them into the tribe.

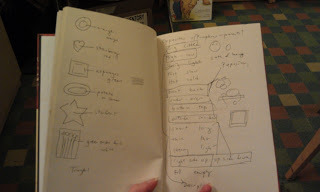

Every day, my notebook sits open on my desk to anchor me with its calm, practical list of tasks to complete (and cross off, oh frabjous joy), to accept notes on phone calls and voicemails and manuscript thinking sessions, to doodle in during meetings, to draft letters or note random phrases for flap copy. When I talk to writers, I usually take notes on our conversation for later, so my notebooks contain sloppily scribbled transcripts of my first conversations with Francisco X. Stork and Karen Rivers and Trent Reedy. Here I have notes from a brainstorming session on what concepts should be included in Food for Thought: The Complete Book of Concepts for Growing Minds.

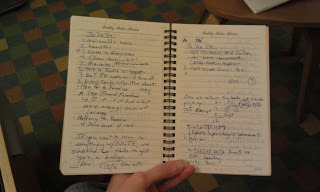

And every night, the last thing I do before I leave work is make my to-do list for the next day.

For this day in November 2007, for instance, I wrote "Notes for Francisco" (on an early draft of Marcelo in the Real World), "Email Yurika" (the foreign rights agent for Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit), "Fact sheet copy," and "Clean desk a bit?" (The question mark is telling.) I also brainstormed titles for the book that eventually became Crossing to Paradise , by Kevin Crossley-Holland, and apparently received voicemails from a couple of agents. Thus, as you can see, the notebooks are fun historical documents as well as useful ones . . . the diaries of my working life.

Here are my collected notebooks from 2001 through today:

I keep them because I never know when I might need to make contact with someone I spoke to on the phone about a project in April 2006 -- and I really have used these for information like that! I have also become very particular about the qualities of my notebooks through the years. A good working notebook has to open flat. Either a wire binding or a standard glued binding can work, but glued is slightly preferable, as then the wire doesn't dig into my hand when I write on the left-hand page. The notebook indeed has to be wide enough to hold my whole hand as I write, and/or have few enough pages that my wrist is still supported on the desk. And I like lined paper, but with the lines a decent distance apart, so my handwriting doesn't have to be any more crabbed than it already is when I write quickly. I don't know if many other editors use them -- any editorial readers: Do you? -- but I do give notebooks like this to new editorial assistants, to provide a home for all the many notes they have to take on procedures, and to welcome them into the tribe.

Every day, my notebook sits open on my desk to anchor me with its calm, practical list of tasks to complete (and cross off, oh frabjous joy), to accept notes on phone calls and voicemails and manuscript thinking sessions, to doodle in during meetings, to draft letters or note random phrases for flap copy. When I talk to writers, I usually take notes on our conversation for later, so my notebooks contain sloppily scribbled transcripts of my first conversations with Francisco X. Stork and Karen Rivers and Trent Reedy. Here I have notes from a brainstorming session on what concepts should be included in Food for Thought: The Complete Book of Concepts for Growing Minds.

And every night, the last thing I do before I leave work is make my to-do list for the next day.

For this day in November 2007, for instance, I wrote "Notes for Francisco" (on an early draft of Marcelo in the Real World), "Email Yurika" (the foreign rights agent for Moribito: Guardian of the Spirit), "Fact sheet copy," and "Clean desk a bit?" (The question mark is telling.) I also brainstormed titles for the book that eventually became Crossing to Paradise , by Kevin Crossley-Holland, and apparently received voicemails from a couple of agents. Thus, as you can see, the notebooks are fun historical documents as well as useful ones . . . the diaries of my working life.

Published on August 24, 2012 05:30

August 23, 2012

Narrative Breakdowns, Muggles Editing, Getting a Job, Overseas Travel, and Lovely Links

About a year and a half ago ago, my fiance, James Monohan, who is a video editor and director, decided that he wanted to start a podcast to talk about story questions, and thus The Narrative Breakdown was born. (I cannot even type those words without hearing "Narrative duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh Breakdown duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh Narrative duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh Breakdown duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh The Narrative Breakdown" in James's voice, as that is a rough approximation of our theme song, which both cracks me up and makes me do a little groove. It is well worth the listen.) We only recorded three trial episodes last year before our schedules got in the way, but we are back this week with a discussion of Beginnings & Inciting Incidents, pivoting off my blog post on the subject last Saturday. James goes on to chat in Part II with our friend Jack Tomas, screenwriter and proud ubernerd, who discusses the concept of Inciting Incidents as it applies to many of pop culture's biggest properties and this summer's hit movies. We hope to be doing these much more regularly going forward. Do please check the podcast out, subscribe on iTunes, give us a rating if you like it, and enjoy!

About a year and a half ago ago, my fiance, James Monohan, who is a video editor and director, decided that he wanted to start a podcast to talk about story questions, and thus The Narrative Breakdown was born. (I cannot even type those words without hearing "Narrative duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh Breakdown duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh Narrative duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh Breakdown duh-duh-duh-duh-DUM-duh The Narrative Breakdown" in James's voice, as that is a rough approximation of our theme song, which both cracks me up and makes me do a little groove. It is well worth the listen.) We only recorded three trial episodes last year before our schedules got in the way, but we are back this week with a discussion of Beginnings & Inciting Incidents, pivoting off my blog post on the subject last Saturday. James goes on to chat in Part II with our friend Jack Tomas, screenwriter and proud ubernerd, who discusses the concept of Inciting Incidents as it applies to many of pop culture's biggest properties and this summer's hit movies. We hope to be doing these much more regularly going forward. Do please check the podcast out, subscribe on iTunes, give us a rating if you like it, and enjoy!And that is not the only podcast I'm on this week! Keith Hawk and John Granger of Mugglecast Academia kindly had me on their show to talk about being an editor, particularly my role as the continuity editor on Half-Blood Prince and Deathly Hallows. It was a fun conversation that includes some reflections on the HP series and some advice on getting a job in publishing (which I also know I still need to write about here).

Did I ever mention this blog post on the CBC Diversity website about how I got into publishing? It's probably the best account of my own story I've ever written up -- though I just noticed I did exclude the detail that Arthur thought I was a pothead during our interview, thanks to my red eyes (I was wearing my contacts). He was very kind to have faith in me and let me write reader's reports anyway.

For those of you who wonder why editors don't take unsolicited submissions: As of 8 a.m. this morning, four days after my query-open period began, I have 238 new queries in my inbox. Clearly this is a more concentrated dose than usual or than would happen if I were open all the time. But goodness. If you did not receive a confirmation e-mail (and ONLY if you did not receive a confirmation e-mail, as apparently most people did within 24 hours), you may resend your submission, using the exact same subject line as on your original submission, to CBKedit at gmail dot com, and then e-mail me separately at chavela_que at yahoo dot com with just your name and title. I will reply next week via Yahoo and confirm that those manuscripts got through.

(I have to admit, I am getting VERY testy with people who are not obeying the query instructions -- sending manuscripts to my other addresses, putting elements out of order. They are the world's most straightforward submissions directions, and they are not hard, so it does not make a great first impression if you're not paying attention and obeying them. And if you HAVE messed them up, don't send the ms. again to make up for it. Just go forth and sin no more.)

If you would like a guaranteed way to be able to submit to me in future, I am very happy to announce I'll be at SCBWI Hawaii on February 22 and 23, 2013! I'll be offering both my Plot Master Class to a small group on the Friday and participating in the general conference on the Saturday (with Lin Oliver, who's always fabulous). While a full schedule/registration will be online in November, anyone who's interested now can e-mail the RA, Lynne Wikoff, at lwikoff at lava dot net to get instructions for the Master Class and get on a mailing list for future info.

In other travel news, I'm going to be in Singapore for five days and Thailand for eight later this fall -- my first-ever trip across the Pacific, and I am very excited. If you have recommendations for things to do or see or ways to avoid jet lag, they'd be much appreciated.

Loose links:

My author Vicky Alvear Shecter, of Cleopatra's Moon fame, did a great guest post on finding and writing the emotional truth of historical events.And my author Bill Konigsberg, of next summer's thought-provoking and hilarious Openly Straight, wrote about what it's like to work with me on a first pass. ALL my authors will recognize those Post-Its. Last night I went to see a Fringe Festival NYC improv show called Help Jane Austen Write the Next Big YA Novel. It was not very Jane Austen-y, but it WAS pretty funny, and I enjoyed it thoroughly. I loved these thoughts from the sadly late Remy Charlip on the physicality of books, especially picture books, and how that affects their narrative flow.And McSweeney's Ultimate Guide to Writing Better Than You Normally Do made me, a person who teaches others to Write Better Than They Normally Do, wince a little bit as I laughed. Recommended to anyone who has read a few too many writing books.

Published on August 23, 2012 05:24

August 21, 2012

The Quote File: Ursula K. LeGuin

I haven't read nearly enough of Ursula K. LeGuin's work, but everything I have read leaves me in awe of her intelligence, empathy, high standards, and grace. Most recently, I thought of "The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas" every time I read about the Penn State horror; her "Hypothesis" effectively and efficiently destroys the pretensions of those who say genrefic can't be literature; and I reread Very Far Away from Anywhere Else at least once a year. . . . If you are or were a sensitive, smart teenager searching for connection and meaning in the vast future, you might think, like I do, it's one of the best YA novels of all time.

A very small collection of Ms. LeGuin's wisdom:

The art of words can take us beyond anything we can say in words.

We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.

A writer is a person who cares what words mean, what they say, how they say it. Writers know words are their way towards truth and freedom, and so they use them with care, with thought, with fear, with delight. By using words well they strengthen their souls. Story-tellers and poets spend their lives learning that skill and art of using words well. And their words make the souls of their readers stronger, brighter, deeper. – from “Advice to a Young Writer”

It is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope.

People who deny the existence of dragons are often eaten by dragons. From within.

What sane person could live in this world and not be crazy?

We're each of us alone, to be sure. What can you do but hold your hand out in the dark.

Love doesn't just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; re-made all the time, made new.

– from The Lathe of Heaven

When action grows unprofitable, gather information; when information grows unprofitable, sleep. – from The Left Hand of Darkness

A very small collection of Ms. LeGuin's wisdom:

The art of words can take us beyond anything we can say in words.

We read books to find out who we are. What other people, real or imaginary, do and think and feel is an essential guide to our understanding of what we ourselves are and may become.

A writer is a person who cares what words mean, what they say, how they say it. Writers know words are their way towards truth and freedom, and so they use them with care, with thought, with fear, with delight. By using words well they strengthen their souls. Story-tellers and poets spend their lives learning that skill and art of using words well. And their words make the souls of their readers stronger, brighter, deeper. – from “Advice to a Young Writer”

It is above all by the imagination that we achieve perception, and compassion, and hope.

People who deny the existence of dragons are often eaten by dragons. From within.

What sane person could live in this world and not be crazy?

We're each of us alone, to be sure. What can you do but hold your hand out in the dark.

Love doesn't just sit there, like a stone, it has to be made, like bread; re-made all the time, made new.

– from The Lathe of Heaven

When action grows unprofitable, gather information; when information grows unprofitable, sleep. – from The Left Hand of Darkness

Published on August 21, 2012 05:13

August 20, 2012

Query Holiday Guidelines

As announced earlier this month, I am open to unsolicited submissions from this very moment -- Monday, August 20, at 8 a.m. -- until Friday, August 24, at 11:59 p.m. To submit, please use the following guidelines (adapted from the ones for the SCBWI Winter Conference--but they HAVE changed, so don't refer to those):

You can see my general "What I'm Looking For" at the Submissions page on my website. You should also check out the Books page on my website and the "Books I Edit" label to the right to see more about the kinds of things I publish. Genrewise, I'm always pretty much looking for everything -- picture books, middle-grade, YA, mystery, fantasy, romance; what's important to me is the freshness of the voice and idea, the quality of the writing and story, and the depth of the characters and the emotions explored. Expanding on this: The writer and blogger Caleb Crain once defined "depth" as "a sense of the complexity of reality," and that's precisely what I mean when I say I'm looking for a novel with literary depth: I want fiction that presents the complexity of reality (which could be a funny or romantic reality as well as a tragic one--indeed, most realities are in more than one mode), and writers who can make those realities tangible and meaningful. Open up a new e-mail to CBKEdit at gmail dot com. Agented submissions should continue to go to my work e-mail address.In the subject line, put the code word SUMMER SQUID, your n ame, and the title of your manuscript. ("SQUID" is a nickname I've long used in affectionate reference to slush-pile manuscripts; I eventually decided it stands for "Submissions, Queries, and Unsolicited Interesting Documents").In the body of the e-mail, please include the following elements in this order:Your nameThe title of the manuscriptThe format/age/genre of the manuscript. To keep this simple, include any of these options as appropriate: Picture Book / Easy Reader / Chapter Book / Middle Grade / Young Adult / Nonfiction / Fantasy / Mystery / Romance / Paranormal / Historical / PoetryA portion of the manuscript as follows:Picture Book: complete textNovel (whatever age): the first chapterNonfiction / Poetry Collection / Etc.: the first ten pagesYour query letter, including your contact information, and a flap-copy-like summary of the work as a whole.If you are an author-illustrator with a picture book text that you want to illustrate, I suggest any of the following methods: (a) paste the full text here, then include one sample illustration in the body of the e-mail; (b) paste the full text here, then put a link to your website in the query letter so I can see your style; (c) if you have a full dummy available online (the best option), simply include a link in your query -- no need to paste in the text. I am able to read HTML submissions, which will retain manuscript formatting; I am also able to read plain text, whichever you send and prefer. Please do not send attachments. I do not care about any formatting questions beyond the inclusion of the elements above in the order I specified them, so please don't ask them. You will receive an automatic reply letting you know your manuscript has been received. It says that you will get a response within six months, and I will do my best to keep to that. I have often failed to stay within these expectations in the past, which I regret, but I'm doing the best I can. SUMMER SQUID Submissions received after 11:59 p.m. on Friday will be deleted unread. As with my submissions through the regular mail, if I am interested, I will send you some personal response; if not, you will receive a form letter. Due to the demands created by the many manuscripts I receive and edit, I will not be able to correspond further than this if I am not interested. Thank you for your interest, and I look forward to seeing your work.

You can see my general "What I'm Looking For" at the Submissions page on my website. You should also check out the Books page on my website and the "Books I Edit" label to the right to see more about the kinds of things I publish. Genrewise, I'm always pretty much looking for everything -- picture books, middle-grade, YA, mystery, fantasy, romance; what's important to me is the freshness of the voice and idea, the quality of the writing and story, and the depth of the characters and the emotions explored. Expanding on this: The writer and blogger Caleb Crain once defined "depth" as "a sense of the complexity of reality," and that's precisely what I mean when I say I'm looking for a novel with literary depth: I want fiction that presents the complexity of reality (which could be a funny or romantic reality as well as a tragic one--indeed, most realities are in more than one mode), and writers who can make those realities tangible and meaningful. Open up a new e-mail to CBKEdit at gmail dot com. Agented submissions should continue to go to my work e-mail address.In the subject line, put the code word SUMMER SQUID, your n ame, and the title of your manuscript. ("SQUID" is a nickname I've long used in affectionate reference to slush-pile manuscripts; I eventually decided it stands for "Submissions, Queries, and Unsolicited Interesting Documents").In the body of the e-mail, please include the following elements in this order:Your nameThe title of the manuscriptThe format/age/genre of the manuscript. To keep this simple, include any of these options as appropriate: Picture Book / Easy Reader / Chapter Book / Middle Grade / Young Adult / Nonfiction / Fantasy / Mystery / Romance / Paranormal / Historical / PoetryA portion of the manuscript as follows:Picture Book: complete textNovel (whatever age): the first chapterNonfiction / Poetry Collection / Etc.: the first ten pagesYour query letter, including your contact information, and a flap-copy-like summary of the work as a whole.If you are an author-illustrator with a picture book text that you want to illustrate, I suggest any of the following methods: (a) paste the full text here, then include one sample illustration in the body of the e-mail; (b) paste the full text here, then put a link to your website in the query letter so I can see your style; (c) if you have a full dummy available online (the best option), simply include a link in your query -- no need to paste in the text. I am able to read HTML submissions, which will retain manuscript formatting; I am also able to read plain text, whichever you send and prefer. Please do not send attachments. I do not care about any formatting questions beyond the inclusion of the elements above in the order I specified them, so please don't ask them. You will receive an automatic reply letting you know your manuscript has been received. It says that you will get a response within six months, and I will do my best to keep to that. I have often failed to stay within these expectations in the past, which I regret, but I'm doing the best I can. SUMMER SQUID Submissions received after 11:59 p.m. on Friday will be deleted unread. As with my submissions through the regular mail, if I am interested, I will send you some personal response; if not, you will receive a form letter. Due to the demands created by the many manuscripts I receive and edit, I will not be able to correspond further than this if I am not interested. Thank you for your interest, and I look forward to seeing your work.

Published on August 20, 2012 05:00

August 19, 2012

Five Things I Love about Leah Bobet's ABOVE

1. The voice.

What got my attention first, from the second and third paragraphs of the book:

2. The perfect match between plot and theme.

Shortly after the underground world of Safe is established as a place where outcasts from Above can receive care and acceptance, an old enemy -- a former resident -- invades Safe, kills its founder, and forces many of its residents to flee to Above . . . which is actually the everyday contemporary world we live in, which is also the world they fear most. As Matthew, the narrator and protagonist, tries to figure out how he can defeat the enemy and reclaim his home, he also discovers the secret history of Safe, and that his beloved home has never been as much of a refuge for all as he believed. But can you admit everyone into your refuge, and what are the limits of that generosity? What happens to people when they stay inside their safe borders all the time, by their own will or by others'? How do community myths form, and how are they maintained? Who can you save -- or can you save anyone?

The story's events keep pushing Matthew back toward these questions, and then he has to make choices about them and take action from the results, which leads to more story events and more questions: the perfect match between plot and theme. Above is a book about insiders and outsiders, myths and truths, safety and isolation vs. openness to experience. It's thinking through these real-world moral and ethical problems using fictional people and events -- but the thinking never feels heavy-handed or moralistic, because we care so much about the characters and their problems are so real. And I get really excited about books that are about things, and especially ones where the thinking-through is as intelligent and the emotion as real as it is here.

3. A true love story.

Matthew's quest to regain his home isn't the only plot in the book; he is also desperately in love with Ariel, a girl who can shapeshift into a bee. Ariel is from Above, while Matthew was born in Safe, and that among other things makes her a little bit unknowable to him. But he tries as hard as he can to know her and to keep her safe. . . . I am an absolute sucker for a good romance between flawed, real people -- it is probably my favorite plot in fiction, to be honest -- and there are moments in this book that just made my heart split open with their realness and beauty.

4. The entirely human, entirely matter-of-fact diversity.

I'll acknowledge upfront that it's kind of weird and self-reflexive to call this out, like Look! People of color! People romantically interested in the same gender! All of it presented as just human and not anything of note!, when clearly the very praise itself indicates it's something of note. But the truth is that such a presentation can still be rare enough in fiction, especially YA fantasy, that it IS actually of note, and it's also something I really value in fiction, and it's done right here.

So: Matthew? Half-Punjabi, half-French Canadian, with fish scales down his back. The strongest, most stable, and long-lasting relationship? Between two ladies. The wisest person in the book? A Native woman medical doctor -- not wise because she is Native by any means, in the stereotyped wisdom-of-savages way, but the fact that she grew up on a reservation means that she has a specific opinion about the book's situation, which comes directly out of her personal experience. It was such a pleasure to see all of these people brought together not in a showy way -- a la the Look! People of color! bit cited above -- but simply in honest community, with all of the compromises and joys that entails.

5. A protagonist who takes responsibility for his actions and grows thereby.

Another way that Jane Austen has influenced my life: I love protagonists who are brought to see the truth of their actions, who recognize and admit their mistakes, and who keep trying. That is where the real work of character happens, in those recognitions and continuations, and that's ultimately what makes a lot of coming-of-age novels satisfying, I think: that sense that the character is improving as a person, and will continue on the right track even after the novel ends. That happens for Matthew here, and his new wisdom in the face of the community's turmoil feels both momentarily surprising, and ultimately reassuring and right.

This is a powerful, painful, gorgeous book -- not for all readers, but what book is? And if you like beautiful writing, love stories, personal stories, marvelous imagination, terrific debuts, and/or thinking about big questions through narrative, it is well worth your time. Do check it out.

Related links:

Rebecca Rabinowitz's review: "Above has stunning prose and went straight to my heart, for reasons artistic and political; for story; and for how story, character, politics, and prose are one."The Tor.com review: "Bobet’s prose stands up to the task she sets before it: telling a complicated and fantastical story of a bloody, dangerous, heart-twisting coming of age"The Publishers Weekly starred review Interviews with Leah: How she wrote and sold the book (and how the story came about) On Inclusivity and Exclusivity in FictionOn dystopian literature (though it isn't actually a dystopian book, please note) Leah's website

What got my attention first, from the second and third paragraphs of the book:

It's half past three already, and nobody awake except for Hide and Mack and Mercy and me, unloading our week's ration of scuffed-up bottles and tins into the broad-wide kitchen cabinets. Most supply nights that's all there is to it: the swish and thunk of stacking tins, the slow quiet of faucets stopping, pipes sleeping, water mains humming lower as the city Above goes to bed. The air moves slower with everyone laid asleep; gets dustier, goes back to earth. There's a light by the kitchens, run by a wire drawn down off the old subway tracks, and the rest is feel-your-way dark until morning, when Jack Flash lights the lamps with a flick of his littlest finger.Obviously these lines raise a lot of intriguing story questions (why do these people collect scuffed-up bottles and tins? Why are they underground? How can this guy light the lamps with his finger?), and those were interesting. But what was more important to me was the obvious authority in the voice, as I was talking about in the previous post: the control Leah demonstrates in setting a tone and doling out details. The lines about "the slow quiet of faucets stopping" and "The air moves slower" themselves are slow and quiet, with a murmuring, rolling-on rhythm, which draws me into the world through the sound of the prose, as well as what it's describing. She doesn't say outright that this happens underground, but trusts us readers to figure it out through phrases like "the city Above" or "the old subway tracks" -- and I love novelists who have faith in me as a reader, whose own obvious intelligence requires me to pay attention. The caps on "Curse" and "Pass" indicate this place has its own language, its own ways of showing meaning, different from our regular world. And finally, some of those phrases are just beautiful, like "feel-your-way dark" and "sparks jumping out of things to kiss at his knuckles." These virtues captured me immediately and inspired me to want to read on.

Jack's got a good Curse. He might have made it Above if not for the sparks always jumping out of things to kiss at his knuckles. Me, the only thing good 'bout my Curse is that I can still Pass. And that's half enough to keep me out of trouble.

2. The perfect match between plot and theme.

Shortly after the underground world of Safe is established as a place where outcasts from Above can receive care and acceptance, an old enemy -- a former resident -- invades Safe, kills its founder, and forces many of its residents to flee to Above . . . which is actually the everyday contemporary world we live in, which is also the world they fear most. As Matthew, the narrator and protagonist, tries to figure out how he can defeat the enemy and reclaim his home, he also discovers the secret history of Safe, and that his beloved home has never been as much of a refuge for all as he believed. But can you admit everyone into your refuge, and what are the limits of that generosity? What happens to people when they stay inside their safe borders all the time, by their own will or by others'? How do community myths form, and how are they maintained? Who can you save -- or can you save anyone?

The story's events keep pushing Matthew back toward these questions, and then he has to make choices about them and take action from the results, which leads to more story events and more questions: the perfect match between plot and theme. Above is a book about insiders and outsiders, myths and truths, safety and isolation vs. openness to experience. It's thinking through these real-world moral and ethical problems using fictional people and events -- but the thinking never feels heavy-handed or moralistic, because we care so much about the characters and their problems are so real. And I get really excited about books that are about things, and especially ones where the thinking-through is as intelligent and the emotion as real as it is here.

3. A true love story.

Matthew's quest to regain his home isn't the only plot in the book; he is also desperately in love with Ariel, a girl who can shapeshift into a bee. Ariel is from Above, while Matthew was born in Safe, and that among other things makes her a little bit unknowable to him. But he tries as hard as he can to know her and to keep her safe. . . . I am an absolute sucker for a good romance between flawed, real people -- it is probably my favorite plot in fiction, to be honest -- and there are moments in this book that just made my heart split open with their realness and beauty.

4. The entirely human, entirely matter-of-fact diversity.

I'll acknowledge upfront that it's kind of weird and self-reflexive to call this out, like Look! People of color! People romantically interested in the same gender! All of it presented as just human and not anything of note!, when clearly the very praise itself indicates it's something of note. But the truth is that such a presentation can still be rare enough in fiction, especially YA fantasy, that it IS actually of note, and it's also something I really value in fiction, and it's done right here.

So: Matthew? Half-Punjabi, half-French Canadian, with fish scales down his back. The strongest, most stable, and long-lasting relationship? Between two ladies. The wisest person in the book? A Native woman medical doctor -- not wise because she is Native by any means, in the stereotyped wisdom-of-savages way, but the fact that she grew up on a reservation means that she has a specific opinion about the book's situation, which comes directly out of her personal experience. It was such a pleasure to see all of these people brought together not in a showy way -- a la the Look! People of color! bit cited above -- but simply in honest community, with all of the compromises and joys that entails.

5. A protagonist who takes responsibility for his actions and grows thereby.

Another way that Jane Austen has influenced my life: I love protagonists who are brought to see the truth of their actions, who recognize and admit their mistakes, and who keep trying. That is where the real work of character happens, in those recognitions and continuations, and that's ultimately what makes a lot of coming-of-age novels satisfying, I think: that sense that the character is improving as a person, and will continue on the right track even after the novel ends. That happens for Matthew here, and his new wisdom in the face of the community's turmoil feels both momentarily surprising, and ultimately reassuring and right.

This is a powerful, painful, gorgeous book -- not for all readers, but what book is? And if you like beautiful writing, love stories, personal stories, marvelous imagination, terrific debuts, and/or thinking about big questions through narrative, it is well worth your time. Do check it out.

Related links:

Rebecca Rabinowitz's review: "Above has stunning prose and went straight to my heart, for reasons artistic and political; for story; and for how story, character, politics, and prose are one."The Tor.com review: "Bobet’s prose stands up to the task she sets before it: telling a complicated and fantastical story of a bloody, dangerous, heart-twisting coming of age"The Publishers Weekly starred review Interviews with Leah: How she wrote and sold the book (and how the story came about) On Inclusivity and Exclusivity in FictionOn dystopian literature (though it isn't actually a dystopian book, please note) Leah's website

Published on August 19, 2012 20:42

August 18, 2012

Some Lists about First Pages

A few months ago, I helped judge a contest where I read a bunch of first pages for YA novels all in one sitting -- about forty of them in the course of three hours. And by the end of it, I have to say, I had seen quite a lot of:

Contemporary first-person protagonists:

Who are cynical or world-weary (especially evinced by rolling their eyes, and/or sarcastic remarks to whatever parent is present)Who blame themselves for something that happened in the past (often an accident)Who are outcasts and either (a) proud of it or (b) self-loathing for itAll of the aboveWith parents:

Who are goofy-quirkyWho are SO MEAN and DON'T UNDERSTAND Who are dying of some disease Who are already dead (often thanks to some accident or other circumstances the protagonist didn't prevent; see #2 above) Or who:

Live in a land ravaged by war or ecological disaster (post-apocalyptic)Have some kind of paranormal magical power, often involving death BothAll of these things are perfectly fine elements in fiction, actually. . . . I could rattle off YA novels I love that have each of these things. I only object to them when these elements are broadcast (as they often were in these contest entries) on the first page, often in the first paragraph--like a mini-synopsis right at the very beginning:

Chiefly, this demonstrates what I think of as "conceptitis" -- a common ailment among first pages, where the writer is so excited about the concept of the novel that s/he gives that concept away on page 1. Or in this case, a whole mess of concepts: conflict with the mother, high and deadly politics in the fantasy world of Columbakron, a missing father, an unlikely assassin. It's hard for me to have a sense of where the story is going because there are so many stories on the page right here, so, as a reader, I feel more confused than drawn in.Periana is also starting us off with her emotional volume already at 11--screaming at her mother as she runs away. Because I as a reader haven't seen any of the circumstances that led to this screaming and running, I feel more alienated from her than connected to her. It's usually better to start softer and give your protagonist some emotional room to play with.I was talking to a writer earlier this year about my exhaustion with first-person teen or preteen protagonists who are angry or whine all the time, and she said, "But that's how my kids talk to me, so that's an authentic teen voice, isn't it?"And that is true--it's authentic to one of the voices and emotional registers that teenagers often use. But it's hardly their most attractive voice, quite often, especially if it involves constant conflict or whining; and it's one that's really hard to connect with, I think, especially if there's no charm or truth or humor to the whininess. So really, I don't want to read a teen voice that echoes how your kids talk to you--I want to read one that sounds like how your kids talk to their friends, with that honesty and humanity and a wider range of emotion than you parents might see from them. Actually, I even want to see how you (the writer/parent) talked to your friends when you were a teenager--omitting the slang of the period, maybe, but with that same emotional authenticity. Protagonists should never, ever whine unless they know they're doing it and they're aware that it's bad behavior. (This might be just my pet peeve, but lord, I hate whiners.)Elbow-jogging the reader with as-yet-unnecessary details that clog up the storytelling, like the stepfather's name and the beauty of Velatrinia.The deadly poisonous left toe is clearly ridiculous, but some days it feels like the only paranormal ability someone has not yet written about. And the "real father" gambit is so common that it makes me roll my eyes a little. Which is not to say it's not true or believable or a necessary element in many stories--the search to know oneself by knowing one's family; only that because it's so common, I wouldn't lead with it on page 1. Hook the reader with some other elements first. I understand that writers are told over and over again to capture a reader on Page 1; I've probably given that advice myself at some point. But I believe that the number-one thing that hooks readers is authority, by which I mean a sense that this writer is in control of the story and how it's being told. An author with authority isn't in a rush to give away the central plotline of the book, because s/he knows that plot is going to be good, and so s/he can afford to take her time getting there, and to do it right. Nor is s/he sucking up or desperate to attract the reader, which is often how a case of conceptitis comes off, and which often loses my respect in turn. Rather, s/he can offer little details, hints, shafts of light illuminating the characters and world that's about to unfold for us, and help us get anchored within that world, so once the action truly begins, we readers have an emotional relationship of some kind with the place and the characters.

The author can take that time because s/he still makes all of this backstory build up steadily to the Inciting Incident, which happens by the end of the first chapter if not earlier -- and s/he knows it's a good Incident, an event that's not only interesting and noteworthy all on its own, but one that sets up clear lines of action and/or questions that will follow out of it, so there's more story there that I want to know about. And s/he has good, strong, confident prose that draws me in by showing me the protagonist and world. This formula describes:

The Golden CompassIntriguing hint in the first line: Mention of "daemons," with no explanation of what they are (ever, really; Philip Pullman is like the honey badger and doesn't care if you keep up)Getting to know the world and character: Lyra is in a clearly alternate Oxford, and she dares to both explore forbidden territory and hide in a wardrobe to eavesdrop.Inciting Incident in first chapter: The arrival of Lord Asriel, and the attempt on his lifeThe Hunger GamesIntriguing hint in the first paragraph: Katniss's obvious love for her sister, who needs comfort, because "This is the day of the reaping." Getting to know the world and character: District 12 is poor, and Katniss needs and likes to huntInciting Incident: The reaping Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's StoneIntriguing hint in the first line: The phrase "perfectly normal, thank you very much"Getting to know the world and character: the contrast between the Dursleys and the Potters and their respective worldsInciting Incident: Hagrid's delivery of Harry to the Dursleys via Dumbledore The Fault in Our StarsIntriguing hint in the first line: The disjunction between Hazel's behavior and the fact that she implicitly asserts she is not depressed; also, the specificity with which she lists those symptomsGetting to know the world and character: observations of her Support Group

Inciting Incident: Hazel meets Augustus Stealing Air (by Trent Reedy, forthcoming in October; I know Trent will be embarrassed to be included in this company, but his first chapter works for exactly the same reasons these others do)Intriguing hint in the first line: "Great success through great risk"Getting to know the character and world: Brian does take a risk in stepping up to try to make friends, and we get a good sense of layout of this small town as he later tries to escape the parkInciting Incident: Fight with Frankie, and Max's rocketbikeStudy those models; take your time; show us the character and world; have a good Inciting Incident; and finally claim your authority, and readers will follow. I've said it before and will say it again: Write your novel like you're performing a striptease, not going to a nude beach.

++++

One blog business thing: In response to a request, I added a "Subscribe via e-mail" button there at the right. Thank you for your interest!

Contemporary first-person protagonists:

Who are cynical or world-weary (especially evinced by rolling their eyes, and/or sarcastic remarks to whatever parent is present)Who blame themselves for something that happened in the past (often an accident)Who are outcasts and either (a) proud of it or (b) self-loathing for itAll of the aboveWith parents:

Who are goofy-quirkyWho are SO MEAN and DON'T UNDERSTAND Who are dying of some disease Who are already dead (often thanks to some accident or other circumstances the protagonist didn't prevent; see #2 above) Or who:

Live in a land ravaged by war or ecological disaster (post-apocalyptic)Have some kind of paranormal magical power, often involving death BothAll of these things are perfectly fine elements in fiction, actually. . . . I could rattle off YA novels I love that have each of these things. I only object to them when these elements are broadcast (as they often were in these contest entries) on the first page, often in the first paragraph--like a mini-synopsis right at the very beginning:

"Periana!" I heard my mother call as I fled into the woods.

I threw back my head and screamed "LEAVE ME ALONE!"

"I hate her," I whined to myself. She was such a harpy! Ever since my stepfather, Varrow Rai, became High Archon of Columbakron, she had been on my back for me to stumble into his archenemy, the beautiful Archoniess Velatrinia, and step on her foot with my deadly poisonous left toe. I knew my real father would never ask me to do anything so degrading--if only my mother would tell me where he was.To enumerate the faults here (and I made that example up, in case you couldn't tell):

Chiefly, this demonstrates what I think of as "conceptitis" -- a common ailment among first pages, where the writer is so excited about the concept of the novel that s/he gives that concept away on page 1. Or in this case, a whole mess of concepts: conflict with the mother, high and deadly politics in the fantasy world of Columbakron, a missing father, an unlikely assassin. It's hard for me to have a sense of where the story is going because there are so many stories on the page right here, so, as a reader, I feel more confused than drawn in.Periana is also starting us off with her emotional volume already at 11--screaming at her mother as she runs away. Because I as a reader haven't seen any of the circumstances that led to this screaming and running, I feel more alienated from her than connected to her. It's usually better to start softer and give your protagonist some emotional room to play with.I was talking to a writer earlier this year about my exhaustion with first-person teen or preteen protagonists who are angry or whine all the time, and she said, "But that's how my kids talk to me, so that's an authentic teen voice, isn't it?"And that is true--it's authentic to one of the voices and emotional registers that teenagers often use. But it's hardly their most attractive voice, quite often, especially if it involves constant conflict or whining; and it's one that's really hard to connect with, I think, especially if there's no charm or truth or humor to the whininess. So really, I don't want to read a teen voice that echoes how your kids talk to you--I want to read one that sounds like how your kids talk to their friends, with that honesty and humanity and a wider range of emotion than you parents might see from them. Actually, I even want to see how you (the writer/parent) talked to your friends when you were a teenager--omitting the slang of the period, maybe, but with that same emotional authenticity. Protagonists should never, ever whine unless they know they're doing it and they're aware that it's bad behavior. (This might be just my pet peeve, but lord, I hate whiners.)Elbow-jogging the reader with as-yet-unnecessary details that clog up the storytelling, like the stepfather's name and the beauty of Velatrinia.The deadly poisonous left toe is clearly ridiculous, but some days it feels like the only paranormal ability someone has not yet written about. And the "real father" gambit is so common that it makes me roll my eyes a little. Which is not to say it's not true or believable or a necessary element in many stories--the search to know oneself by knowing one's family; only that because it's so common, I wouldn't lead with it on page 1. Hook the reader with some other elements first. I understand that writers are told over and over again to capture a reader on Page 1; I've probably given that advice myself at some point. But I believe that the number-one thing that hooks readers is authority, by which I mean a sense that this writer is in control of the story and how it's being told. An author with authority isn't in a rush to give away the central plotline of the book, because s/he knows that plot is going to be good, and so s/he can afford to take her time getting there, and to do it right. Nor is s/he sucking up or desperate to attract the reader, which is often how a case of conceptitis comes off, and which often loses my respect in turn. Rather, s/he can offer little details, hints, shafts of light illuminating the characters and world that's about to unfold for us, and help us get anchored within that world, so once the action truly begins, we readers have an emotional relationship of some kind with the place and the characters.

The author can take that time because s/he still makes all of this backstory build up steadily to the Inciting Incident, which happens by the end of the first chapter if not earlier -- and s/he knows it's a good Incident, an event that's not only interesting and noteworthy all on its own, but one that sets up clear lines of action and/or questions that will follow out of it, so there's more story there that I want to know about. And s/he has good, strong, confident prose that draws me in by showing me the protagonist and world. This formula describes:

The Golden CompassIntriguing hint in the first line: Mention of "daemons," with no explanation of what they are (ever, really; Philip Pullman is like the honey badger and doesn't care if you keep up)Getting to know the world and character: Lyra is in a clearly alternate Oxford, and she dares to both explore forbidden territory and hide in a wardrobe to eavesdrop.Inciting Incident in first chapter: The arrival of Lord Asriel, and the attempt on his lifeThe Hunger GamesIntriguing hint in the first paragraph: Katniss's obvious love for her sister, who needs comfort, because "This is the day of the reaping." Getting to know the world and character: District 12 is poor, and Katniss needs and likes to huntInciting Incident: The reaping Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's StoneIntriguing hint in the first line: The phrase "perfectly normal, thank you very much"Getting to know the world and character: the contrast between the Dursleys and the Potters and their respective worldsInciting Incident: Hagrid's delivery of Harry to the Dursleys via Dumbledore The Fault in Our StarsIntriguing hint in the first line: The disjunction between Hazel's behavior and the fact that she implicitly asserts she is not depressed; also, the specificity with which she lists those symptomsGetting to know the world and character: observations of her Support Group

Inciting Incident: Hazel meets Augustus Stealing Air (by Trent Reedy, forthcoming in October; I know Trent will be embarrassed to be included in this company, but his first chapter works for exactly the same reasons these others do)Intriguing hint in the first line: "Great success through great risk"Getting to know the character and world: Brian does take a risk in stepping up to try to make friends, and we get a good sense of layout of this small town as he later tries to escape the parkInciting Incident: Fight with Frankie, and Max's rocketbikeStudy those models; take your time; show us the character and world; have a good Inciting Incident; and finally claim your authority, and readers will follow. I've said it before and will say it again: Write your novel like you're performing a striptease, not going to a nude beach.

++++

One blog business thing: In response to a request, I added a "Subscribe via e-mail" button there at the right. Thank you for your interest!

Published on August 18, 2012 12:57

August 17, 2012

"Security," by William Stafford

Tomorrow will have an island. Before night

I always find it. Then on to the next island.

These places hidden in the day separate

and come forward if you beckon.

But you have to know they are there before they exist.

Some time there will be a tomorrow without any island.

So far, I haven't let that happen, but after

I'm gone others may become faithless and careless.

Before them will tumble the wide unbroken sea,

and without any hope they will stare at the horizon.

So to you, Friend, I confide my secret:

to be a discoverer you hold close whatever

you find, and after a while you decide

what it is. Then, secure in where you have been,

you turn to the open sea and let go.

I always find it. Then on to the next island.

These places hidden in the day separate

and come forward if you beckon.

But you have to know they are there before they exist.

Some time there will be a tomorrow without any island.

So far, I haven't let that happen, but after

I'm gone others may become faithless and careless.

Before them will tumble the wide unbroken sea,

and without any hope they will stare at the horizon.

So to you, Friend, I confide my secret:

to be a discoverer you hold close whatever

you find, and after a while you decide

what it is. Then, secure in where you have been,

you turn to the open sea and let go.

Published on August 17, 2012 13:30

August 15, 2012

Six Reasons Why Everything in Publishing Takes So Long

Publishing takes so long because . . .

1. Because each book is individual.

The beautiful and difficult thing about publishing is that it's a one-to-one industry: one writer connecting to one reader at a time. And because everything is individual, there are absolutely zilch solid rules in this business (beyond "Have a sense of humor" and "Don't be a jerk"). Each author is different; each manuscript is different; each editor is different; each agent is different; each publishing house is different. No matter how many books an editor and author have worked on together, each new manuscript has to be considered on its own strengths, with its own problems.

Aesthetically terrible books get published and make a ton of money; aesthetically brilliant books win the National Book Award; other aesthetically terrible books cost their publishers piles of cash with very little return; other aesthetically brilliant books disappear completely. In adult publishing, Alice Sebold, Charles Frazier, Audrey Niffenegger and Sara Gruen (to pick four names in a very common pattern) all experienced incredible success with their first novels, leading to advances for their second novels in the multiple millions; and not one of those second novels has achieved the success of their previous books. I heard anecdotally (and this may not be true) that Markus Zusak and The Book Thief ended up on Good Morning America because a publicity assistant at Knopf made a mistake and sent a copy directly to Charlie Gibson, who saw it sitting on his assistant’s desk and picked it up out of curiosity. If that did happen, there's no way to guarantee it happening again, and thus it illustrates my point: Every book is individual, and a success not easily replicable.

2. Because editors and agents have many submissions to wade through, because . . .

2A. . . . The barriers to being a writer who submits manuscripts are extremely low.

This is not a complaint or an accusation or anything pejorative, just a factual observation: Writing is an individual pursuit, that anyone who is literate can participate in, with extremely low technological requirements (as technological requirements go in the modern age). As a result, all you need to write and submit a manuscript is the ability to write in English, access to a computer with word-processing software, and an Internet account so you can send out the resulting manuscript. (You no longer even need a printer! Or stamps!) So a lot of people can participate in this process, and do.

2B. . . . Writers vastly outnumber editors and agents — especially when writers multiply submit.

We are also living in an unprecedented age of access to information about publishers and editors and agents, thanks to the Internet, Amazon, acknowledgment pages, writers’ discussion boards, QueryTracker, you name it. This makes it extremely easy for writers to research places to submit their work, and to send forth manuscripts accordingly to all the places they find.

I am not complaining about multiple submissions, please note; I understand why writers and agents do it, and those reasons are 100% valid. But if we think of the amount of time spent reading a query as quantity X, then one writer submitting to one agent equals a reading time of X across the whole industry. One writer submitting to six agents equals 6X across the industry. Six writers submitting to six agents each equals 36X (though note we still have just those same six agents doing six times the work) . . . and so it all grows exponentially, and crowds out the time for other things within the industry. Again, these are not complaints, just facts.

2C. . . . Reading is inherently not fast.

The very smart Jason Pinter once wrote something on Twitter like, "The average person reads 250 words per minute -- 60 pages an hour. If you give someone your 350-page manuscript, you're asking them to spend the length of a flight from New York to California with you talking to them." His point was that you should do your best to be sure that you're good company, which is true. But no matter how good the company is, it takes a lot more than just sitting down to listen to a three-minute song, or watch a 30-minute TV show. . . . I have days when I wish I could fly back and forth from New York to California to get all my reading done.

3. Because each book has both aesthetic and economic factors that must be carefully weighed at each step in the process.

I remember once in my first year as an editorial assistant, I fell in love with a picture-book manuscript and took it in to my afternoon meeting with Arthur. “I love this manuscript,” I said. “Will you read it right now?”

“Sure, leave it with me,” he said.

“It’s not even two complete pages,” I said. “Can’t you just look at it?”

“No, I can’t,” he said patiently. “Leave it here and we’ll talk about it tomorrow.”

Now that I’ve had manuscripts thrust at me at conferences, and been that editor facing an intern with a great manuscript in hand, I understand where he was coming from. Because each manuscript — even a two-hundred-word picture book text — presents an editor with a series of questions to be answered, to wit:

Is this any good in an aesthetic sense?Is it of any interest in a publishing sense? Is it appropriate for our publishing house? Do I like this?*If it is some good aesthetically, but not perfect, what parts aren't working?Can those parts be made to work?Assuming yes to question #6: Are the good parts good enough, and the publishing interest strong enough, to justify the editorial time and energy in trying to make it work?Assuming yes to question #7: Is this strong enough as it is to try to acquire it? Or should I request a noncontractual revision? Is the author capable of revising it? (Some writers simply are no good at revising.) Is s/he someone we'll want to work with for the long term or just this book?How much do we think the book will sell? Following on #11, how much should we pay for it? Assuming no to question #7: How should this be rejected?If it’s a picture book: Who could or should illustrate it? What is Dream Illustrator's schedule like? How much would we have to pay him/her? Etc. Sometimes those answers come very quickly: If the answer to the first three and sometimes four questions are “no,” everything else is simple. But naming the bad parts takes time; writing a letter to the author takes time; figuring out whether the book is of publishing interest or whether, say, five other books on the same topic have just been published takes time. And of course, just plain reading the manuscript takes time!

And if I do decide I want to acquire it, there's a whole other to-do list after that (and then another one after that), which keeps coming back to evaluating the book's artistic and publishing strengths and how they can be maximized. Publishing is an extremely long-term game, and long-term games aren't fast.

* N. B. Many years ago, back when I was an assistant with time to do freelance editing, an author I was working with said, "I have the feeling you don't like my book." I realized then that I didn't care whether I liked the project, actually, because I was committed to editing it either way; I cared only whether the book worked, whether it accomplished the task it was meant to do, because then the book (and my work) would have been successful, and my personal feelings about the project were irrelevant. It's very different from my job now, where, if I'm going to put in all the time and effort that I do put in to a manuscript, and stand before my acquisitions committee, sales force, and the world and say, "You should pay attention to this," I want to feel emotionally connected to the project, and to feel like it's worthy of that attention.

4. Because each draft is a wholly new artistic work and must be considered as such.

I can't just read the two chapters or five lines that were changed from the previous draft to this; I have to consider them in the context of the whole, to see how the whole makes me feel now, and therefore whether the revision is working. (This is not so true in later stages of novels, after I've read the book six times and we're polishing moments; but it is true early on, and always true with picture books.) Then see #2C above.

5. Because what is individual is often deeply personal, and people deserve kindness.

I love my authors, and I often know their spouses’ names, their children’s names, where they’re from, when they’re going on vacation and where. When I have bad news, I want to present it to them in the kindest and most supportive way possible. When I have good news, I want to celebrate with them in a way that feels present. I have relationships with agents, and I want to give them smart feedback on projects so they'll keep thinking I'm worth submitting to even when I say no (as I frequently must). When I read manuscripts, I'm very aware that every one is a little piece of the writer's soul there on the page for me -- like a good Horcrux -- and that if I'm turning it down, I need to do so with at least politeness. In a world that grows ever more rushed and demanding, time spent is a compliment, and I want to pay that compliment to the people who are important to me.

6. Because we're trying to make beautiful things that matter here and share them with other people who will love them too.

And that takes time, in the writing and thinking and editing and painting and copywriting and publicizing and selling and reading and telling; and that's all there is to it.

1. Because each book is individual.

The beautiful and difficult thing about publishing is that it's a one-to-one industry: one writer connecting to one reader at a time. And because everything is individual, there are absolutely zilch solid rules in this business (beyond "Have a sense of humor" and "Don't be a jerk"). Each author is different; each manuscript is different; each editor is different; each agent is different; each publishing house is different. No matter how many books an editor and author have worked on together, each new manuscript has to be considered on its own strengths, with its own problems.

Aesthetically terrible books get published and make a ton of money; aesthetically brilliant books win the National Book Award; other aesthetically terrible books cost their publishers piles of cash with very little return; other aesthetically brilliant books disappear completely. In adult publishing, Alice Sebold, Charles Frazier, Audrey Niffenegger and Sara Gruen (to pick four names in a very common pattern) all experienced incredible success with their first novels, leading to advances for their second novels in the multiple millions; and not one of those second novels has achieved the success of their previous books. I heard anecdotally (and this may not be true) that Markus Zusak and The Book Thief ended up on Good Morning America because a publicity assistant at Knopf made a mistake and sent a copy directly to Charlie Gibson, who saw it sitting on his assistant’s desk and picked it up out of curiosity. If that did happen, there's no way to guarantee it happening again, and thus it illustrates my point: Every book is individual, and a success not easily replicable.

2. Because editors and agents have many submissions to wade through, because . . .

2A. . . . The barriers to being a writer who submits manuscripts are extremely low.