Cheryl B. Klein's Blog, page 9

September 20, 2012

Good People of Seattle! I Have a Mission for You!

Over a year ago, Arthur and I were contacted by the Make-A-Wish Foundation regarding a young Seattle-area writer named Stephanie Trimberger (who was 13 at the time; she’s 15 now). Stephanie has brain cancer, and her dream was to have her novel edited by “the Harry Potter editors.” Arthur and I read it and wrote her an editorial letter, and she began working on revisions. A year went by, and we didn’t hear anything more. Then last week, we heard that she had finished her book and wanted us to take one last look.

Thanks to the terrific coordination of a lot of people at Scholastic, we not only managed to edit it quickly, but our designers typeset the manuscript and created a gorgeous cover for it. And with the help of an extraordinarily generous donation from the printer, Command Web, three hundred copies of Stephanie’s THE RUBY HEART have now been printed.

Your Mission, Seattle Area People!: Next Tuesday, September 25, at 6 p.m., Stephanie will be doing a reading and signing of her book at the Pacific Place Barnes & Noble. Will you please, please attend? It would be so very awesome to have a big audience there to applaud her accomplishment and make it a great day for her. Stephanie is a huge reader of YA and fantasy fiction; she lost her mom to brain cancer nine years ago, and it sounds like she’s been writing about that long. I’m sure ALL writers can sympathize with her dream of publishing a book, and it should be an amazing evening in seeing that dream fulfilled.

The details in full:

Tuesday, September 256 p.m. (it was scheduled for 5:30 earlier; the time has been moved back)Barnes & Noble Pacific Place

600 Pine Street, Suite 107

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 265-0156

You can RSVP or leave a message for Stephanie at the Facebook page for the event. Thank you!

Thanks to the terrific coordination of a lot of people at Scholastic, we not only managed to edit it quickly, but our designers typeset the manuscript and created a gorgeous cover for it. And with the help of an extraordinarily generous donation from the printer, Command Web, three hundred copies of Stephanie’s THE RUBY HEART have now been printed.

Your Mission, Seattle Area People!: Next Tuesday, September 25, at 6 p.m., Stephanie will be doing a reading and signing of her book at the Pacific Place Barnes & Noble. Will you please, please attend? It would be so very awesome to have a big audience there to applaud her accomplishment and make it a great day for her. Stephanie is a huge reader of YA and fantasy fiction; she lost her mom to brain cancer nine years ago, and it sounds like she’s been writing about that long. I’m sure ALL writers can sympathize with her dream of publishing a book, and it should be an amazing evening in seeing that dream fulfilled.

The details in full:

Tuesday, September 256 p.m. (it was scheduled for 5:30 earlier; the time has been moved back)Barnes & Noble Pacific Place

600 Pine Street, Suite 107

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 265-0156

You can RSVP or leave a message for Stephanie at the Facebook page for the event. Thank you!

Published on September 20, 2012 04:18

September 15, 2012

Breaking Down Bond -- James Bond.

This week on The Narrative Breakdown, James and I go beat-by-beat through this delightful scene from the 2006 version of Casino Royale. We chose this scene because it never ceases to please me extremely in its wit, sexiness, and -- as you'll hear us realize in talking about this -- really well-done power dynamics. Not to mention it offers excellent characterizations, perfect scene structure, a great example of subtext-becoming-text, and of course, discussion of Daniel Craig's derriere. So if you are interested in learning about any of those things:

Subscribe in iTunes

Listen on the show page

Shamefully for us, we did not give credit to the screenwriters within the episode: They are Robert Wade and Neil Purvis, who have together written all of the Bond movies in the last thirteen years, and more interestingly,

Published on September 15, 2012 11:26

September 9, 2012

Another New Episode of The Narrative Breakdown -- Now with More Bird!

We have another new episode of The Narrative Breakdown* live here at our iTunes page, and it's a really fun one this week: As the start of a new series on scene construction, screenwriter Matt Bird joins us to discuss strategies by which characters try to get what they want in a scene. As you know if you follow his blog The Cockeyed Caravan, Matt is a certifiable writing-craft genius, offering terrific tools like "The Ultimate Story Checklist" and essay series on "The Storyteller's Rulebook" and "How to Build a Scene." (And as my kidlit readers might know, he is married to the illustrious Betsy.) He has a TON of terrific ideas and insights to offer on both developing characters and showing their behavior playing out in a scene, and James and I had such a great time talking to him that at one point we ran out of disk space to record our conversation (a mistake we quickly corrected, obviously). Please check it out!

We have another new episode of The Narrative Breakdown* live here at our iTunes page, and it's a really fun one this week: As the start of a new series on scene construction, screenwriter Matt Bird joins us to discuss strategies by which characters try to get what they want in a scene. As you know if you follow his blog The Cockeyed Caravan, Matt is a certifiable writing-craft genius, offering terrific tools like "The Ultimate Story Checklist" and essay series on "The Storyteller's Rulebook" and "How to Build a Scene." (And as my kidlit readers might know, he is married to the illustrious Betsy.) He has a TON of terrific ideas and insights to offer on both developing characters and showing their behavior playing out in a scene, and James and I had such a great time talking to him that at one point we ran out of disk space to record our conversation (a mistake we quickly corrected, obviously). Please check it out!_____________

* A copyediting-dork digression: In writing this, I experienced a brief bit of existential doubt at how The Chicago Manual of Awesome would style something so lowly and unofficial as a podcast. . . . Would it be in roman and quote marks, a la an episode of a TV show? Or all caps, as I've done it before here as per Internet style? Or just a link? I'm going with itals as this is the title of a real show, dammit; and hence it shall be forevermore.

Published on September 09, 2012 07:05

Another New Episode of The Narrative Breakdown -- Now with More Bird

We have another new episode of The Narrative Breakdown* live here at our iTunes page, and it's a really fun one this week: As the start of a new series on scene construction, screenwriter Matt Bird joins us to discuss strategies by which characters try to get what they want in a scene. As you know if you follow his blog The Cockeyed Caravan, Matt is a certifiable writing-craft genius, offering terrific tools like "The Ultimate Story Checklist" and essay series on "The Storyteller's Rulebook" and "How to Build a Scene." (And as my kidlit readers might know, he is married to the illustrious Betsy.) He has a TON of terrific ideas and insights to offer on both developing characters and showing their behavior playing out in a scene, and James and I had such a great time talking to him that at one point we ran out of disk space to record our conversation (a mistake we quickly corrected, obviously). Please check it out!

We have another new episode of The Narrative Breakdown* live here at our iTunes page, and it's a really fun one this week: As the start of a new series on scene construction, screenwriter Matt Bird joins us to discuss strategies by which characters try to get what they want in a scene. As you know if you follow his blog The Cockeyed Caravan, Matt is a certifiable writing-craft genius, offering terrific tools like "The Ultimate Story Checklist" and essay series on "The Storyteller's Rulebook" and "How to Build a Scene." (And as my kidlit readers might know, he is married to the illustrious Betsy.) He has a TON of terrific ideas and insights to offer on both developing characters and showing their behavior playing out in a scene, and James and I had such a great time talking to him that at one point we ran out of disk space to record our conversation (a mistake we quickly corrected, obviously). Please check it out!_____________

* A copyediting-dork digression: In writing this, I experienced a brief bit of existential doubt at how The Chicago Manual of Awesome would style something so lowly and unofficial as a podcast. . . . Would it be in roman and quote marks, a la an episode of a TV show? Or all caps, as I've done it before here as per Internet style? Or just a link? I'm going with itals as this is the title of a real show, dammit; and hence it shall be forevermore.

Published on September 09, 2012 07:05

September 5, 2012

New Episode of THE NARRATIVE BREAKDOWN now live!

This time, James and our friend Jason Ginsburg discuss generating and developing science-fiction and fantasy story concepts and ideas. I had the pleasure of seeing both The Avengers and Prometheus with Jason and James this summer (and Jason's wife Wendy), and our guest host knows his stuff. Please check it out on iTunes, and rate and review the show if you enjoy!

While I'm here, a quick Summer Movie Report Card:

The Avengers: A-. Maybe a little bit too long, but Joss Whedon's dialogue and sense of humor + great relationships + terrific action + shawarma = the most enjoyable thing I've seen this year, I think.

Prometheus: D+ -- and even that is entirely based on how pretty the whole thing was, most especially Michael Fassbender (though still not as wonderful as he was as Mr. Rochester, because my word, his Mr. Rochester!). The characters were idiots (especially as scientists!) and the plot made no sense at all. But truly a nice use of the film's CGI budget. Maybe it will be redeemed in the Director's Cut.

The Dark Knight Rises: B-? After the brilliant intensity of The Dark Knight, that thrilling and terrifying examination of the worth of human beings as a class and as individuals (through the Joker's nihilism vs. Batman's goodness vs. Harvey Dent's whole journey), this came off as a little bit scattered to me, with too many stories to cram in, not enough time to develop any of the relationships, an all-over-the-place economic vision, and not as much thematic coherency as the previous movie. I also think the story put itself at a disadvantage by having to spend so much time convincing Batman to come out of retirement . . . It starts slow and then has to cram things together later, with many, many plot holes along the way. But wonderful visuals, as ever, and all the actors acquitted themselves nicely, especially Anne Hathaway.

If you're a Christopher Nolan fan, you must see this -- useful for punctuating conversations as well: The Inception Button.

Ruby Sparks: B+. I have quibbles with the ending, but up until then, this is a smart and thoughtful take on writing, relationships, and the dangers of creating or applying the former through/to the latter. I loved the sequence where he was creating Ruby's character especially. And hooray for a female screenwriter and co-director! Highly recommended for writers and people who love them.

Beasts of the Southern Wild: I don't even know how to grade this movie, it's so unlike anything else I've ever seen. An A for its heroine and her performance, for sure; an A for the beauty of its visuals; an A for originality and imagination; a N/A for plot structure.

The Amazing Spider-Man: B+. The best parts of this by far to me were the conversations between Peter and Mary Jane, when the real spark between Andrew Garfield and Emma Stone seemed to imbue their characters as well. Those also seemed like the only times Andrew Garfield smiled -- I wanted to love him, wanted him to be my fun-loving Spidey superhero, but his performance seemed to actively resist offering any emotional warmth to me as a viewer, which left me a bit confused. But a good, creepy villain and Martin Sheen being wise are always pleasures.

Still would like to see (and now might have to catch on DVD): The Bourne Legacy, Premium Rush, The Campaign, Brave, Seeking a Friend at the End of the World, Snow White and the Huntsman, Searching for Sugar Man. Anything else you'd recommend?

While I'm here, a quick Summer Movie Report Card:

The Avengers: A-. Maybe a little bit too long, but Joss Whedon's dialogue and sense of humor + great relationships + terrific action + shawarma = the most enjoyable thing I've seen this year, I think.

Prometheus: D+ -- and even that is entirely based on how pretty the whole thing was, most especially Michael Fassbender (though still not as wonderful as he was as Mr. Rochester, because my word, his Mr. Rochester!). The characters were idiots (especially as scientists!) and the plot made no sense at all. But truly a nice use of the film's CGI budget. Maybe it will be redeemed in the Director's Cut.

The Dark Knight Rises: B-? After the brilliant intensity of The Dark Knight, that thrilling and terrifying examination of the worth of human beings as a class and as individuals (through the Joker's nihilism vs. Batman's goodness vs. Harvey Dent's whole journey), this came off as a little bit scattered to me, with too many stories to cram in, not enough time to develop any of the relationships, an all-over-the-place economic vision, and not as much thematic coherency as the previous movie. I also think the story put itself at a disadvantage by having to spend so much time convincing Batman to come out of retirement . . . It starts slow and then has to cram things together later, with many, many plot holes along the way. But wonderful visuals, as ever, and all the actors acquitted themselves nicely, especially Anne Hathaway.

If you're a Christopher Nolan fan, you must see this -- useful for punctuating conversations as well: The Inception Button.

Ruby Sparks: B+. I have quibbles with the ending, but up until then, this is a smart and thoughtful take on writing, relationships, and the dangers of creating or applying the former through/to the latter. I loved the sequence where he was creating Ruby's character especially. And hooray for a female screenwriter and co-director! Highly recommended for writers and people who love them.

Beasts of the Southern Wild: I don't even know how to grade this movie, it's so unlike anything else I've ever seen. An A for its heroine and her performance, for sure; an A for the beauty of its visuals; an A for originality and imagination; a N/A for plot structure.

The Amazing Spider-Man: B+. The best parts of this by far to me were the conversations between Peter and Mary Jane, when the real spark between Andrew Garfield and Emma Stone seemed to imbue their characters as well. Those also seemed like the only times Andrew Garfield smiled -- I wanted to love him, wanted him to be my fun-loving Spidey superhero, but his performance seemed to actively resist offering any emotional warmth to me as a viewer, which left me a bit confused. But a good, creepy villain and Martin Sheen being wise are always pleasures.

Still would like to see (and now might have to catch on DVD): The Bourne Legacy, Premium Rush, The Campaign, Brave, Seeking a Friend at the End of the World, Snow White and the Huntsman, Searching for Sugar Man. Anything else you'd recommend?

Published on September 05, 2012 17:08

August 31, 2012

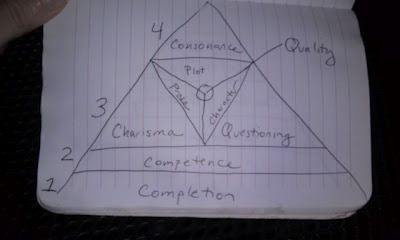

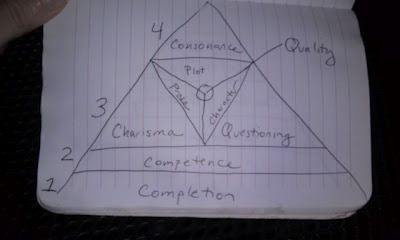

Theory: The Klein Pyramid of Literary Quality

I am finishing out this month of blogging (hooray!) with a theory I've been working on for some time. Last February, thanks to John Green's The Fault in Our Stars -- which I loved intensely and immensely -- I was thinking about Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs and how it might apply to literary judgments. That is, to use the books within the book of The Fault in Our Stars (which form an important part of the narrative), what makes The Price of Dawn (an action-adventure novel based on a video game) better or worse than An Imperial Affliction (a literary novel about life, love, death, and the existence of God)? Is one better or worse? How do we decide that? And for me, in my real-world daily life: What makes one manuscript better than another on a solely literary basis? To answer these questions, I hereby present, as a hypothesis up for discussion, the Klein Pyramid of Literary Quality:

Someday I will figure out how to master WordArt and make a proper computer diagram of this. Until then, to take these from the bottom (lowest level) up:

1. COMPLETION. The literary work is complete. (Lots of writers never even get here -- a completed manuscript -- so truly, this counts for something.)

2. COMPETENCE. The literary work is readable and understandable by a reader who is not the author.

3. CHARISMA. The literary work is able to make you feel the emotion the writer intends you-the-reader to feel, so well as that intention can be discerned. (While the subject of intention is clearly nebulous and much debated, I feel as if it is safe to say Pride and Prejudice is intended to make a reader laugh, for example, while Pet Sematary is intended to scare us, and any romance novel is intended to make readers fall in love along with the characters.)

3. QUALITY. The literary work displays some measure of imagination, originality, and/or accomplishment in at least once of these areas: Prose, Character, Plot. Ideally, all three aspects of the Quality triangle will work together to contribute to the book's Charisma or Questioning or both.

3. QUESTIONING. The literary work intentionally asks and answers questions about our human existence. (See above for caveats on intention.)

4. CONSONANCE. The literary work successfully integrates all of the above into a meaningful and beautiful whole. Consonance books are masterpieces.

How to Use This Pyramid: To measure the literary quality of the work, you fill in all the triangles/trapezoids the particular work has achieved according to you, the reader. The darker the pyramid, the better the book is. A book must have all of the triangles/trapezoids of the previous level filled in to advance to the next level. Thus, for me, The Fault in Our Stars would be one solid dark triangle, because I think it does everything well, up to and including Consonance. But Twilight would be a dark trapezoid at the bottom (Levels 1 and 2) with just the Charisma triangle filled in above it, as it totally caught me up in the feelings of falling in love, even as I was not overly impressed by any of its Quality attributes, and I don't think Ms. Meyer especially intended to Question anything. An intensely didactic picture book might fill in Levels 1 and 2 but then have only the Questioning triangle complete, as it's asking how we should live and then answering that question, but with no emotional appeal (Charisma) at all.

Each judgment would be peculiar to its reader and the date s/he read the work, as opinions vary widely and can change over time; but that is where half the fun of literary discussion comes in, as one reader might say "Oh, this book was totally Charismatic for me!" and another would sniff, "Hmph. It barely achieved Competence!" The more widely it is agreed a book fills up the pyramid, the closer to classic status it moves in the public eye. And this pyramid has nothing to do with sales or other financial success; it is for aesthetic judgments only.

There are two more concepts that I've puzzled over whether and how to include them in the pyramid: the ideas of Pleasure and Ethics. Gone with the Wind, for instance, would have earned Consonance from me when I read it in seventh grade, and it Pleased me intensely at the time, but it's also a book rife with racial stereotypes; should it then not be allowed to achieve Consonance in my judgment, because its Ethics are bad? Or Waiting for Godot is likewise Consonant for me, but I hated reading it (I've never seen it staged): Can it then not be Consonant because I didn't take Pleasure in it? (I guess there was some Pleasure in recognizing the mastery of the construction, how completely the Quality of its plot, characters, and prose contributed to the Questioning and Charisma it wanted to achieve; but none of that really made up for my desire for someone to move, dammit.) (Also, clearly, I would have to come up with synonyms for "Pleasure" and "Ethics" that start with K sounds.)

What do you think? Are there categories I've left out that should be included in any future revision to the Pyramid? Would YOU include Pleasure and/or Ethics, and how, and what would you call them? What books have you read this year that you would call Consonant and why?

I would be delighted to hear thoughts here! And thanks to anyone who's stuck around and read my posts through all of this month; I've really enjoyed the writing of them, and appreciate your attention.

Someday I will figure out how to master WordArt and make a proper computer diagram of this. Until then, to take these from the bottom (lowest level) up:

1. COMPLETION. The literary work is complete. (Lots of writers never even get here -- a completed manuscript -- so truly, this counts for something.)

2. COMPETENCE. The literary work is readable and understandable by a reader who is not the author.

3. CHARISMA. The literary work is able to make you feel the emotion the writer intends you-the-reader to feel, so well as that intention can be discerned. (While the subject of intention is clearly nebulous and much debated, I feel as if it is safe to say Pride and Prejudice is intended to make a reader laugh, for example, while Pet Sematary is intended to scare us, and any romance novel is intended to make readers fall in love along with the characters.)

3. QUALITY. The literary work displays some measure of imagination, originality, and/or accomplishment in at least once of these areas: Prose, Character, Plot. Ideally, all three aspects of the Quality triangle will work together to contribute to the book's Charisma or Questioning or both.

3. QUESTIONING. The literary work intentionally asks and answers questions about our human existence. (See above for caveats on intention.)

4. CONSONANCE. The literary work successfully integrates all of the above into a meaningful and beautiful whole. Consonance books are masterpieces.

How to Use This Pyramid: To measure the literary quality of the work, you fill in all the triangles/trapezoids the particular work has achieved according to you, the reader. The darker the pyramid, the better the book is. A book must have all of the triangles/trapezoids of the previous level filled in to advance to the next level. Thus, for me, The Fault in Our Stars would be one solid dark triangle, because I think it does everything well, up to and including Consonance. But Twilight would be a dark trapezoid at the bottom (Levels 1 and 2) with just the Charisma triangle filled in above it, as it totally caught me up in the feelings of falling in love, even as I was not overly impressed by any of its Quality attributes, and I don't think Ms. Meyer especially intended to Question anything. An intensely didactic picture book might fill in Levels 1 and 2 but then have only the Questioning triangle complete, as it's asking how we should live and then answering that question, but with no emotional appeal (Charisma) at all.

Each judgment would be peculiar to its reader and the date s/he read the work, as opinions vary widely and can change over time; but that is where half the fun of literary discussion comes in, as one reader might say "Oh, this book was totally Charismatic for me!" and another would sniff, "Hmph. It barely achieved Competence!" The more widely it is agreed a book fills up the pyramid, the closer to classic status it moves in the public eye. And this pyramid has nothing to do with sales or other financial success; it is for aesthetic judgments only.

There are two more concepts that I've puzzled over whether and how to include them in the pyramid: the ideas of Pleasure and Ethics. Gone with the Wind, for instance, would have earned Consonance from me when I read it in seventh grade, and it Pleased me intensely at the time, but it's also a book rife with racial stereotypes; should it then not be allowed to achieve Consonance in my judgment, because its Ethics are bad? Or Waiting for Godot is likewise Consonant for me, but I hated reading it (I've never seen it staged): Can it then not be Consonant because I didn't take Pleasure in it? (I guess there was some Pleasure in recognizing the mastery of the construction, how completely the Quality of its plot, characters, and prose contributed to the Questioning and Charisma it wanted to achieve; but none of that really made up for my desire for someone to move, dammit.) (Also, clearly, I would have to come up with synonyms for "Pleasure" and "Ethics" that start with K sounds.)

What do you think? Are there categories I've left out that should be included in any future revision to the Pyramid? Would YOU include Pleasure and/or Ethics, and how, and what would you call them? What books have you read this year that you would call Consonant and why?

I would be delighted to hear thoughts here! And thanks to anyone who's stuck around and read my posts through all of this month; I've really enjoyed the writing of them, and appreciate your attention.

Published on August 31, 2012 20:54

August 30, 2012

Taking a Stand for Standing

So in the last few months, I have become a standing-desk devotee. My interest in the subject started with articles like this one, which pretty much say that anyone with a computer is doomed to die early from sitting in front of it, and then increased with the apostolism of authors I admire. My excellent (and extremely health-conscious) fiance began talking about it, and I then followed his lead in putting my laptop on various high surfaces in our apartment when I was working--the kitchen counter, a tall dresser. After I got used to the sensation of standing for so long, I came to like it . . . for an hour or two, anyway, at which point I'd sit down for an hour or two in turn. But the variety was fun.

And now I have two standing desks, at work and at home! Here's the work version:

Yes, indeed, that is the extremely advanced standing-desk technology of two cardboard boxes attached to each other, with a mousepad on one and my keyboard on the other. The keyboard is now right at the angle of my elbows, so typing is very comfortable, and my computer screen conveniently tilts up so I can see it easily. I made a side handle out of packing tape so it's easy to whisk it out of the way. I try to follow the policy that if I'm doing e-mail, I have to stand up, while if I'm doing editorial work, it's OK to be sitting down. Other times I just follow an hour-up, hour-down policy. It's gotten to the point that if I do sit for more than an hour or so, I start to feel antsy, and back on my feet I go. (I've also come to mind standing on the subway much less than before.)

At home James and I really did get actual technology involved, as well as some homemade gimcrackery::

We found the treadmill on Craigslist for $80 (it almost cost more to rent a moving van to get it home), and then, as the handles were inconveniently low, we rigged up the temporary solution you see here until we can figure out how to build a permanent frame. The result is more at James's height than it is mine, but it's still effective for us both. James can walk and work for three hours at a time at low speeds; I remain more task- and hour-oriented. Either way, we both enjoy having a little more of a head start on outwalking Death.

We found the treadmill on Craigslist for $80 (it almost cost more to rent a moving van to get it home), and then, as the handles were inconveniently low, we rigged up the temporary solution you see here until we can figure out how to build a permanent frame. The result is more at James's height than it is mine, but it's still effective for us both. James can walk and work for three hours at a time at low speeds; I remain more task- and hour-oriented. Either way, we both enjoy having a little more of a head start on outwalking Death.

And now I have two standing desks, at work and at home! Here's the work version:

Yes, indeed, that is the extremely advanced standing-desk technology of two cardboard boxes attached to each other, with a mousepad on one and my keyboard on the other. The keyboard is now right at the angle of my elbows, so typing is very comfortable, and my computer screen conveniently tilts up so I can see it easily. I made a side handle out of packing tape so it's easy to whisk it out of the way. I try to follow the policy that if I'm doing e-mail, I have to stand up, while if I'm doing editorial work, it's OK to be sitting down. Other times I just follow an hour-up, hour-down policy. It's gotten to the point that if I do sit for more than an hour or so, I start to feel antsy, and back on my feet I go. (I've also come to mind standing on the subway much less than before.)

At home James and I really did get actual technology involved, as well as some homemade gimcrackery::

We found the treadmill on Craigslist for $80 (it almost cost more to rent a moving van to get it home), and then, as the handles were inconveniently low, we rigged up the temporary solution you see here until we can figure out how to build a permanent frame. The result is more at James's height than it is mine, but it's still effective for us both. James can walk and work for three hours at a time at low speeds; I remain more task- and hour-oriented. Either way, we both enjoy having a little more of a head start on outwalking Death.

We found the treadmill on Craigslist for $80 (it almost cost more to rent a moving van to get it home), and then, as the handles were inconveniently low, we rigged up the temporary solution you see here until we can figure out how to build a permanent frame. The result is more at James's height than it is mine, but it's still effective for us both. James can walk and work for three hours at a time at low speeds; I remain more task- and hour-oriented. Either way, we both enjoy having a little more of a head start on outwalking Death.

Published on August 30, 2012 19:07

August 29, 2012

The Editorial Process, Step by Step

(Not the large-scale process, from editorial letter to line-edit to copyedit; but what happens in your brain, letter by letter, word by word, if you too have the editorial bug.)

1. Notice that something feels off to you. It may be a dangling modifier; it may be a mistake in the chronology; it may be as big as the fact that the main character is turning out to be a smarmy jerk or you're bored at a point where the action ought to make you excited; it may be as tiny as an "an" where the author should really have a "the." In any case, like Miss Clavel, you sense that SOMETHING IS NOT RIGHT.

Portrait of the Editor as a Young Nun

Portrait of the Editor as a Young Nun

2. Reread the passage and confirm the presence of wrongness. Look at it again. Is the feeling still there? Or did you just misread the sentence? Oh yeah, it's still there.

3. Identify the problem and the principle it's violating. "A problem well stated is a problem half solved," said Charles Kettering, and indeed zooming in on the problem is half the battle. If it's a spelling, grammatical, punctuation, or style error, the answer is often pretty obvious; you've known those rules for years and you have Merriam-Webster's 14th New Collegiate Dictionary and the Chicago Manual of AWESOME* to back you up. If it's a plot or character problem, you can measure it against Freytag's triangle and other editorial principles inculcated in us over decades, often even without our knowing it: Protagonists should be interesting people, generate energy, and take action; we should see a change in both the character and his or her circumstances from beginning to end; the child character must solve the problem; the climax needs to be the culmination of all that came before it, and so on and so forth.

But sometimes a sentence just sounds wrong. Why? Uh . . . Hrmm. Is the thought coming out of nowhere? Coming in at the wrong time in a paragraph? Are all the words used correctly? Would it be better in active as opposed to passive voice? Is it repeating a word or thought or phrase or sentence rhythm you read (heard, really) in the last two pages or so? Is it just your taste vs. the author's style? Is the sentence actually a violation of the author's style in some way and so you should push him on it? Sometimes it's not until I change the sentence or paragraph to what sounds right to me that I can figure out why something sounds wrong. Until that point, I just stare at it, which is one of the reasons my personal editorial process is extremely slow.

(You can run this whole process on illustrations too, by the way; you just then have to know your visual principles as well as your verbal and narrative ones.)

* This is an in-joke with one of my authors, who prefers to call it the Chicago Manual of Boring.

4. Weigh the problem. Is this worth bringing up with the author? Well, that depends on the nature and severity of the problem, the importance of the principle it's violating, the work that would be required to fix it, where you all are in the editorial process, how much the reader would be likely to notice the problem and care, the other things you're already asking the author to do in this round (and those things might be a higher priority for now, so you could pick this one up in a later draft if it's still an issue then), your understanding of the author's revision capabilities (can she do both small revisions and large-scale ones at the same time, or is it better to save the small ones for later with her? Can he fix plot problems but is utterly hopeless at deepening his characters?), the strength of your authority here (Does the author appreciate your comments or resent them? What if Chicago and Words into Type conflict?), what the author's vision of this book is and whether correcting this would serve that, your knowledge of your personal editorial irritants (because every editor has that one thing that drives them crazy and nobody else, which is then often not worth asking about). . . . Editors truly consider all of these things -- many of them subconsciously in about 2.5 seconds -- in choosing what to query with an author.

5. If it is of sufficient weight: Articulate the problem in a manner tailored to the author and manuscript. Having half solved the problem by stating it clearly for yourself, you now have to state it for the author in a manner that he can appreciate and which will inspire him to take action. Name the problem and the principle it's violating clearly and nonjudgmentally; it's not a personal failure of the author, it's a simple mistake in the manuscript, and mistakes can be corrected. Just as in disagreements in relationships, it's often useful to put things in terms of your own emotional reaction ("Because of [X factor in the manuscript], I felt [Y negative feeling]"), which can again be changed if X factor in the manuscript is changed. Remember that just as the author needs to show-not-tell the story to you, you have to show-not-tell the problems to her, and thus it's useful to back up your assertions with solid examples from the manuscript. Sometimes a series of questions is the best way to show that there's a problem, even if you fear you'll sound stupid; I sometimes call myself the Designated Dumb Lady within a ms. if I'm not getting what's going on, and that frees me up to ask the dumb but necessary questions. Suggest a strategy for a fix (or multiple options for a fix) if you think the author will be open to it and find it useful, but remember it's always the author's choice whether and how to fix it, not yours. (If the author is repeatedly making bad fix choices, from your point of view, then you may not be a good editorial match. Or you may just be too persnickety or egotistical; that's always a possibility worth staying aware of.)

Plot and character stuff usually belongs in an editorial letter; it's extremely useful to know which one is the author's greatest strength or primary interest, if one or the other, so you can couch your argument for making the change in terms of that strength, which might make her feel more excited and capable of doing it. Ditto for the usefulness of knowing what the author's goal for and/or vision of this manuscript is, whether to explore the idea of death or make a reader fall in love with the character or write a really breakneck adventure; you can then phrase your argument for this particular change in service of that (if it truly is; authors are smart and can see when you're going back to the same well too often, so you shouldn't overuse any of these strategies). With mechanical stuff, which you should be saving for the copyediting and proofreading stages anyway, you can usually just say something like, "Hey, Chicago says we should capitalize 'Princess' here--OK?", or the even briefer "Cap as per CMOS 6.24."** Paragraph- and sentence-level stuff is always basically the effort to explain why "an" vs. "the" is so very important (one is a new or random reference; the other refers to something we've already seen in the text) or the equivalent, or what you as a reader WANT to be feeling at this point in the text and why you aren't and how if we can just cut this sentence, please oh please, you will be.

If you are an editor who does multiple passes through a line-edit, like I do, then it's often wise to save your argument for a change for the second or third pass through, so you can reread your suggested change outside the heat of the moment and see whether it's really a problem or if you were just in a weird editorial mood. That happens.

** This reference number not verified in the Chicago Manual.

6. Make sure the author knows you're open to conversation to help them better understand the problem or brainstorm solutions.

7. Hope for a response that fixes or removes the problem in the next draft. If that doesn't happen, then repeat steps #1-6, perhaps making your argument in #5 from a different angle. If it's a small thing, or a thing that is mostly a matter of your taste vs. the author's taste, then consider just letting the issue go. But that depends on what you weighed in #3 (and also how careful you know the author is; some authors get distracted easily and might just have missed a query they'll gratefully address later).

8. Read the next line. If necessary: Repeat.

1. Notice that something feels off to you. It may be a dangling modifier; it may be a mistake in the chronology; it may be as big as the fact that the main character is turning out to be a smarmy jerk or you're bored at a point where the action ought to make you excited; it may be as tiny as an "an" where the author should really have a "the." In any case, like Miss Clavel, you sense that SOMETHING IS NOT RIGHT.

Portrait of the Editor as a Young Nun

Portrait of the Editor as a Young Nun

2. Reread the passage and confirm the presence of wrongness. Look at it again. Is the feeling still there? Or did you just misread the sentence? Oh yeah, it's still there.

3. Identify the problem and the principle it's violating. "A problem well stated is a problem half solved," said Charles Kettering, and indeed zooming in on the problem is half the battle. If it's a spelling, grammatical, punctuation, or style error, the answer is often pretty obvious; you've known those rules for years and you have Merriam-Webster's 14th New Collegiate Dictionary and the Chicago Manual of AWESOME* to back you up. If it's a plot or character problem, you can measure it against Freytag's triangle and other editorial principles inculcated in us over decades, often even without our knowing it: Protagonists should be interesting people, generate energy, and take action; we should see a change in both the character and his or her circumstances from beginning to end; the child character must solve the problem; the climax needs to be the culmination of all that came before it, and so on and so forth.

But sometimes a sentence just sounds wrong. Why? Uh . . . Hrmm. Is the thought coming out of nowhere? Coming in at the wrong time in a paragraph? Are all the words used correctly? Would it be better in active as opposed to passive voice? Is it repeating a word or thought or phrase or sentence rhythm you read (heard, really) in the last two pages or so? Is it just your taste vs. the author's style? Is the sentence actually a violation of the author's style in some way and so you should push him on it? Sometimes it's not until I change the sentence or paragraph to what sounds right to me that I can figure out why something sounds wrong. Until that point, I just stare at it, which is one of the reasons my personal editorial process is extremely slow.

(You can run this whole process on illustrations too, by the way; you just then have to know your visual principles as well as your verbal and narrative ones.)

* This is an in-joke with one of my authors, who prefers to call it the Chicago Manual of Boring.

4. Weigh the problem. Is this worth bringing up with the author? Well, that depends on the nature and severity of the problem, the importance of the principle it's violating, the work that would be required to fix it, where you all are in the editorial process, how much the reader would be likely to notice the problem and care, the other things you're already asking the author to do in this round (and those things might be a higher priority for now, so you could pick this one up in a later draft if it's still an issue then), your understanding of the author's revision capabilities (can she do both small revisions and large-scale ones at the same time, or is it better to save the small ones for later with her? Can he fix plot problems but is utterly hopeless at deepening his characters?), the strength of your authority here (Does the author appreciate your comments or resent them? What if Chicago and Words into Type conflict?), what the author's vision of this book is and whether correcting this would serve that, your knowledge of your personal editorial irritants (because every editor has that one thing that drives them crazy and nobody else, which is then often not worth asking about). . . . Editors truly consider all of these things -- many of them subconsciously in about 2.5 seconds -- in choosing what to query with an author.

5. If it is of sufficient weight: Articulate the problem in a manner tailored to the author and manuscript. Having half solved the problem by stating it clearly for yourself, you now have to state it for the author in a manner that he can appreciate and which will inspire him to take action. Name the problem and the principle it's violating clearly and nonjudgmentally; it's not a personal failure of the author, it's a simple mistake in the manuscript, and mistakes can be corrected. Just as in disagreements in relationships, it's often useful to put things in terms of your own emotional reaction ("Because of [X factor in the manuscript], I felt [Y negative feeling]"), which can again be changed if X factor in the manuscript is changed. Remember that just as the author needs to show-not-tell the story to you, you have to show-not-tell the problems to her, and thus it's useful to back up your assertions with solid examples from the manuscript. Sometimes a series of questions is the best way to show that there's a problem, even if you fear you'll sound stupid; I sometimes call myself the Designated Dumb Lady within a ms. if I'm not getting what's going on, and that frees me up to ask the dumb but necessary questions. Suggest a strategy for a fix (or multiple options for a fix) if you think the author will be open to it and find it useful, but remember it's always the author's choice whether and how to fix it, not yours. (If the author is repeatedly making bad fix choices, from your point of view, then you may not be a good editorial match. Or you may just be too persnickety or egotistical; that's always a possibility worth staying aware of.)

Plot and character stuff usually belongs in an editorial letter; it's extremely useful to know which one is the author's greatest strength or primary interest, if one or the other, so you can couch your argument for making the change in terms of that strength, which might make her feel more excited and capable of doing it. Ditto for the usefulness of knowing what the author's goal for and/or vision of this manuscript is, whether to explore the idea of death or make a reader fall in love with the character or write a really breakneck adventure; you can then phrase your argument for this particular change in service of that (if it truly is; authors are smart and can see when you're going back to the same well too often, so you shouldn't overuse any of these strategies). With mechanical stuff, which you should be saving for the copyediting and proofreading stages anyway, you can usually just say something like, "Hey, Chicago says we should capitalize 'Princess' here--OK?", or the even briefer "Cap as per CMOS 6.24."** Paragraph- and sentence-level stuff is always basically the effort to explain why "an" vs. "the" is so very important (one is a new or random reference; the other refers to something we've already seen in the text) or the equivalent, or what you as a reader WANT to be feeling at this point in the text and why you aren't and how if we can just cut this sentence, please oh please, you will be.

If you are an editor who does multiple passes through a line-edit, like I do, then it's often wise to save your argument for a change for the second or third pass through, so you can reread your suggested change outside the heat of the moment and see whether it's really a problem or if you were just in a weird editorial mood. That happens.

** This reference number not verified in the Chicago Manual.

6. Make sure the author knows you're open to conversation to help them better understand the problem or brainstorm solutions.

7. Hope for a response that fixes or removes the problem in the next draft. If that doesn't happen, then repeat steps #1-6, perhaps making your argument in #5 from a different angle. If it's a small thing, or a thing that is mostly a matter of your taste vs. the author's taste, then consider just letting the issue go. But that depends on what you weighed in #3 (and also how careful you know the author is; some authors get distracted easily and might just have missed a query they'll gratefully address later).

8. Read the next line. If necessary: Repeat.

Published on August 29, 2012 20:52

August 28, 2012

How to Get a Job in Publishing, 2012 Edition

Today was the twelfth anniversary of my first day at Arthur A. Levine Books / Scholastic (as yesterday was the twelfth anniversary of my arrival in New York City), and as such, it seems like a good day to knock out one of the questions I was asked at the beginning of this month of blogging:

How does one get his/her foot in the door at a publishing house? Any tips on how to make oneself stand out when applying for internships or assistant positions?

It is a tough time to be an aspiring editorial assistant, I have to say, as publishers receive literally hundreds of applications for every slot. Here are six things I highly recommend for anyone who wants to get a job at a big publisher these days. (All of these are my opinion based on what I see; none of them are Scholastic HR-department approved, so I could be completely off base; and I'm sure there are also exceptions to every one.) My 2006 post "How do I become a book editor?" is the preliminary reading here.

1. Live in the publisher's area (which means in practice for most jobs: live in New York). There are so many applicants for every slot that HR departments and editors have little incentive to try to interview anyone who lives far outside the publisher's region. . . . After all, why should they require you to go to all the trouble and expense of flying here for an interview when another fifty candidates can come in tomorrow?

2. Do what you can to meet people who already work in the industry. As publishing is an intensely personal business, a lot of jobs happen through personal connections. Many positions get filled by former interns or current employees in other departments. The good news is that you can meet publishing people these days not just through long-established methods like informational interviews and the publishing institutes, but at writer's conferences, if you can find an unpressured time to talk, and in various forums online. I connected with one of my favorite-ever interns through a listserv I belong to, which showed me her enthusiasm for children's literature was genuine and that she was a good writer (even though she didn't live near New York at the time), so when she later asked if we could do an informational interview, I was happy to oblige.

3. Study and practice editing and publishing where you are. Read books about writing. Take a copyediting or proofreading course. Be a beta editor for fan fiction, or even hang your shingle out as a dissertation doctor or freelance editor. Write and submit a little fiction yourself so you know what authors experience. Learn e-book formatting and help a friend self-publish something (or even self-publish your own work to know what that's like). All of these things would be useful experience that would give you valuable practical knowledge long-term, especially in a changing industry; it will diversify the number of jobs you can apply for within said industry, and practice before you get in; and it will help give you a running start when you get a job at last.

Also, if you wouldn't edit something for free, simply out of love of editing and helping a written project become better, you might want to think about going into a different industry. Because if you become an editor, you will spend many nights and weekends on the work of reading, thinking about, and editing books -- which really means you have to love the job enough that you do it even on time that you aren't actively paid for it. If you don't feel that passionate about it, consider another department in publishing, or a more lucrative line of business altogether.

4. Be massively prepared for any contacts or interviews you might have, and try to make connections with editors, not just HR people. Stay up on what's popular in children's literature, and read lots of recently published books in the field. If you are going to meet an editor for an interview of some kind, read at least one of the books he or she has published and have intelligent things to say about it or questions to ask. Try to get an overview of the editor's list as a whole, then think about the qualities he or she values in books, and the place those books hold within the output of the larger publishing house. If you're sending an application cover letter, demonstrated that same sort of knowledge. Have a list ready in your head of your favorite books of all time, the books you've read most recently, and the kind of books you would most want to work on if you could.

5. Be genuine, passionate, and energetic but not obnoxious. When I do informational interviews, I'm most impressed by the people who clearly love books and know their stuff; who are engaged with the world and do things for the love of it, and who are eager to transfer that make-things-happen energy into the publishing industry; who write well, as that's essential in this business; and who have good, calm, non-obsequious manners and a good self-presentation. Don't laugh too much, especially in agreeing with your interviewer, and don't suck up. Be someone I can respect as a possible editorial colleague, with well-thought-through opinions of your own.

6. Do everything right. Of course this is impossible, but in general: Write the very best you can. Proofread the hell out of anything you turn in. Turn it in on time, or before on time. Tailor your work to the publisher (or even better the editor) to whom you're applying. Wear nice interview clothes and send a thank-you note afterward. Do all the basic professional things right, and then go above and beyond in your smarts, insight, and passion for books.

How does one get his/her foot in the door at a publishing house? Any tips on how to make oneself stand out when applying for internships or assistant positions?

It is a tough time to be an aspiring editorial assistant, I have to say, as publishers receive literally hundreds of applications for every slot. Here are six things I highly recommend for anyone who wants to get a job at a big publisher these days. (All of these are my opinion based on what I see; none of them are Scholastic HR-department approved, so I could be completely off base; and I'm sure there are also exceptions to every one.) My 2006 post "How do I become a book editor?" is the preliminary reading here.

1. Live in the publisher's area (which means in practice for most jobs: live in New York). There are so many applicants for every slot that HR departments and editors have little incentive to try to interview anyone who lives far outside the publisher's region. . . . After all, why should they require you to go to all the trouble and expense of flying here for an interview when another fifty candidates can come in tomorrow?

2. Do what you can to meet people who already work in the industry. As publishing is an intensely personal business, a lot of jobs happen through personal connections. Many positions get filled by former interns or current employees in other departments. The good news is that you can meet publishing people these days not just through long-established methods like informational interviews and the publishing institutes, but at writer's conferences, if you can find an unpressured time to talk, and in various forums online. I connected with one of my favorite-ever interns through a listserv I belong to, which showed me her enthusiasm for children's literature was genuine and that she was a good writer (even though she didn't live near New York at the time), so when she later asked if we could do an informational interview, I was happy to oblige.

3. Study and practice editing and publishing where you are. Read books about writing. Take a copyediting or proofreading course. Be a beta editor for fan fiction, or even hang your shingle out as a dissertation doctor or freelance editor. Write and submit a little fiction yourself so you know what authors experience. Learn e-book formatting and help a friend self-publish something (or even self-publish your own work to know what that's like). All of these things would be useful experience that would give you valuable practical knowledge long-term, especially in a changing industry; it will diversify the number of jobs you can apply for within said industry, and practice before you get in; and it will help give you a running start when you get a job at last.

Also, if you wouldn't edit something for free, simply out of love of editing and helping a written project become better, you might want to think about going into a different industry. Because if you become an editor, you will spend many nights and weekends on the work of reading, thinking about, and editing books -- which really means you have to love the job enough that you do it even on time that you aren't actively paid for it. If you don't feel that passionate about it, consider another department in publishing, or a more lucrative line of business altogether.

4. Be massively prepared for any contacts or interviews you might have, and try to make connections with editors, not just HR people. Stay up on what's popular in children's literature, and read lots of recently published books in the field. If you are going to meet an editor for an interview of some kind, read at least one of the books he or she has published and have intelligent things to say about it or questions to ask. Try to get an overview of the editor's list as a whole, then think about the qualities he or she values in books, and the place those books hold within the output of the larger publishing house. If you're sending an application cover letter, demonstrated that same sort of knowledge. Have a list ready in your head of your favorite books of all time, the books you've read most recently, and the kind of books you would most want to work on if you could.

5. Be genuine, passionate, and energetic but not obnoxious. When I do informational interviews, I'm most impressed by the people who clearly love books and know their stuff; who are engaged with the world and do things for the love of it, and who are eager to transfer that make-things-happen energy into the publishing industry; who write well, as that's essential in this business; and who have good, calm, non-obsequious manners and a good self-presentation. Don't laugh too much, especially in agreeing with your interviewer, and don't suck up. Be someone I can respect as a possible editorial colleague, with well-thought-through opinions of your own.

6. Do everything right. Of course this is impossible, but in general: Write the very best you can. Proofread the hell out of anything you turn in. Turn it in on time, or before on time. Tailor your work to the publisher (or even better the editor) to whom you're applying. Wear nice interview clothes and send a thank-you note afterward. Do all the basic professional things right, and then go above and beyond in your smarts, insight, and passion for books.

Published on August 28, 2012 20:56

August 27, 2012

A Ramble List: the Dinner Table Debate, Religion, Bigotry, and Monkey Brains

As they agreed last spring, Brian Brown of the National Organization for Marriage and Dan Savage of the Savage Love column et al. met recently at Mr. Savage's home to debate same-sex marriage. I was fascinated by their conversation, learned some stuff, and think it's worth watching through at least the two opening statements (which would take about twenty minutes). Some observations on this dialogue:

1. They are working from fundamentally different and incompatible definitions of the word "marriage" here. Paraphrasing, Mr. Brown says "Marriage is a covenant between a man and a woman"; Mr. Savage says "Marriage is a gender-neutral package of civil rights and privileges." Mr. Brown does not acknowledge that his covenant includes that civil package -- rights that all same-sex couples are being denied -- while Mr. Savage obviously does not agree that marriage is dependent on differing genders.

2. They're also working from fundamentally different ideas of the purpose of marriage -- though here I suspect Mr. Brown of double-dealing, or maybe just being a bad debater. He says repeatedly that marriage is for procreation, thus subscribing to the only point of marriage that truly excludes gay people . . . but then he also repeatedly fails to address the issue of why heterosexual couples who are unable or unwilling to have children should then be allowed to marry, or whether their marriages are any less valid than those of couples with children. Mr. Savage, for his part, asserts that marriage is for the pleasure, companionship, and support of the two adults involved. I wager Mr. Brown would have agreed with him on this (as at least one aspect of marriage, anyway) up until gay marriage became a major issue in the United States, when he had to retreat to procreation to keep his position at least somewhat intellectually coherent.

3. And in general with language, truth, Scripture, legal and romantic relationships, academic studies, love: There are so many sides to each jewel, and each debater turns the stone in a different direction. Whenever the Regnerus study comes up, Mr. Savage asserts its methodology was flawed; Mr. Brown asserts the methodology was fine, and the only reason it hasn't been repeated was because Mr. Regnerus was so brutally attacked for his study's conclusions. It seems as if there ought to be a scientifically sound way to determine whether the methodology was flawed, but according to the Times article in the link, there are only more things to weigh: whether the child lived with the parents, whether the parents truly lived as gays or lesbians or only had had a same-sex relationship at some point in their lives, the economic status of all involved, the funding of the study — all of which nuances both Mr. Savage and Mr. Brown bring up as evidence for their respective sides. So many facets to every human story.

4. The most irritating thing about this debate for me: In almost every statement Mr. Brown makes, especially his opening one, he comes back to how he and other Christianists* have been called bigots and how much this upsets him -- making this endlessly about himself and his pain. It was the same dynamic that played out in the Chik-Fil-A controversy a few weeks ago, where Christianists bought chicken sandwiches in order to practice their rights to free speech, which were supposedly under threat. While the Boston and Chicago mayors’ claims that they’d ban the chain were definitely stupid, in both cases, the claim to injury was truly an attempt to level the emotional playing field, both at this dinner table and in the media: Our enemies are in pain (here because of the denial of marriage rights); pain creates sympathy for them—pain sells; we need some pain of our own; let us blow up an insult to us to make our pain as great as theirs. Mediawise, I'd agree, the Christianists don't come off well, because it's hard for the media to portray their position without saying "They think God hates gays." But at the end of the day, the vast majority of marriage laws in this country (and all of them at the federal level) still favor the Christianists, so Christianists pretending that the two pains are equal is rather ridiculous.

* As defined by Andrew Sullivan, “Christianists” are "those on the fringes of the religious right who have used the Gospels to perpetuate their own aspirations for power, control and oppression."

5. Which is not to say that Christianists are the only one who practice this dynamic; Jews and Islamists the world over do it; atheists do it; God knows the Republicans and Democrats do it; Mitt Romney and Barack Obama do it; MSNBC and Fox News; Todd Akin has certainly done it in the last few weeks. And all of them (all of us) get rewarded for it with money, media attention, more support from their side. . . . The “fight” instincts in all our little monkey brains light up at being attacked, and into the arena we go.

6. But as a practicing Methodist, I find this particularly troublesome when Christianists do it—when we jump to be offended at the first opportunity. Because if Christianity is about anything at all in practice here on this earth, it is about imaginative empathy with others, about sacrificing one's own ego to share others' pain and take on their burdens. "Love your neighbor as yourself," repeatedly named as the greatest commandment, means that we must imagine ourselves in our neighbors' positions and treat them as we would treat ourselves. Christ's death on the cross was an act of imaginative empathy: It was taking on the sins of the world in order to spare humanity the endless suffering from those sins. Turning the other cheek and offering our cloaks also demands that the other person receive all we have. The New Testament calls us to make this our first priority: to listen, to empathize, to give, to love.

7. This is not to say that there are no limits on this giving, nor that the law does not exist or is nullified; a literal reading of the scripture would certainly make same-sex sex an abomination. But many Christianists seem to see only the law, not the humans behind it, so they don't extend empathy to the genuine pain of a young man who believes passionately in Christ and also falls passionately in love with his male best friend; or to an elderly long-term lesbian couple who cannot be together when one partner goes into the hospital. . . . What to do with empathy when it conflicts with the law is a vexing and vexed question. But in cases like this, where no harm to others has been committed, I believe a Christian's first responsibilities are always to empathy and humility, never to self-satisfaction and simplistic judgment. If we practice these latter things instead, we deny the humble, generous, radically honest and complicated God-in-man we claim to serve.

8. This might sound juvenile, but I keep coming back to this word as the one that best expresses the principle: Above all, Christians should not be mean. People who have power and use it for their own pleasure in causing pain are mean. People who have power and ostentatiously wave it in the face of those who don’t are mean. On the day of the eat-in at Chik-Fil-A, the Christianists who lined up to buy chicken sandwiches were actively demonstrating their distaste for people who have often already suffered and continue to suffer for being the people God made them to be; and that felt to me like a profoundly mean and un-Christian thing to do.

9. I admit I did not behave well during the Chik-Fil-A contretemps myself. A high school classmate made a remark on Facebook that somehow linked the issue to the Muslim community center near Ground Zero. Non-New Yorkers being self-righteous about Ground Zero is one of the things that stirs up MY monkey brain, and the remark was so completely counterfactual (Mayor Bloomberg did not threaten to ban Chik-Fil-A), and the comments supporting it so obviously equally ill-informed and self-satisfied, that I gave into my worse instincts and wrote a dissenting comment. I then tried to be as matter-of-fact as I could in the comments “discussion” that followed, not to submit further to that monkey brain, but I did not succeed fully, and I regret that.

10. Coming back to the debate: I eventually got depressed by the conversation, because nobody’s mind is changed and there is nothing, nothing, these men can agree on. (Peter Sagal pretty much nails the reasons why.) So it simply becomes two angry men who feel aggrieved, speaking forcefully past each other in the same room. And the same thing happened for me on Facebook: I came away from the Chik-Fil-A argument more saddened than anything. In both cases, there was an opportunity for people to meet and talk as generous human beings — over a dinner table, as Facebook “friends” — about differing interpretations of a contentious and deep issue, and that respect, humility, and true conversation did not happen.

11. Perhaps it was overly optimistic even to hope for that sincere conversation on both sides: As Mr. Sagal notes, the identity issues and principles involved are grounded too deeply within Messrs. Savage and Brown for them to be able to detach from them, even if they were genuinely open to doing so. Merriam-Webster’s defines a bigot as "a person who is obstinately or intolerantly devoted to his or her own opinions and prejudices”; and as nobody’s feelings and beliefs are ever entirely rational and proportionate, I imagine there are very few people in the world who are not bigots for something or other. (Or as they sing in Avenue Q, "Everyone's A Little Bit Racist." And yes, readers: I just called every one of you bigots! Ha!) Mr. Brown is a bigot for fundamentalist Christianity and the Christianist doctrines that he sees as following from that; Mr. Savage is a bigot for the freedom to love and marry who he likes. I will happily proclaim I am a bigot in the obstinacy sense for the novels of Jane Austen, gender equality (often known as feminism), and civil same-sex marriage. Perhaps the best we can all do is to recognize our opinions as opinions, try to keep them anchored in objective reality. and then prevent that obstinate bigotry from extending into intolerance, by treating others with respect and kindness even when we disagree.

12. (I disagree with Peter Sagal on one thing: I don't want my Facebook friends punished for disagreeing with me or for eating at Chik-Fil-A. I want them to recognize the humanity of gay people and the validity of their romantic relationships and to change their minds about civil marriage. They can keep objecting to it religiously and eating chicken sandwiches for all I care--they just have to accept that their interpretation of religious truth does not govern Mr. Savage's and my civil lives.)

13. But this can be so hard when the other side of whatever argument has fewer scruples and doesn't behave well as we do, and/or when the feelings run so deep. . . . The biggest argument against religion from my point of view (and really the only argument against it I'd make myself) is that it encourages its practitioners to think they know immutable and eternal truth -- to the extent that I'd wager at least one person who just read that sentence is now offended because, as a practitioner of the _________ faith, they DO know immutable and eternal truth, and I have just implied the matter is a little more fungible. And it is near impossible to see outside that particular kind of immutable and eternal truth, to remember that others might have their own immutable and eternal truths that are just as real to them as ours are to us, and just as valid when weighed against objective reality, if we can even determine such a thing.

14. I'm guilty of this too: Last year, a lovely author and I disagreed profoundly on a manuscript, where I saw it as an X type of book and she saw it as a Z type of book. She did not want to change it in the least toward an X, and I could not make it cohere in my head as a Z. . . . The X type felt immutably right to me, just because of my own experiences as a reader and editor and my bigotry (I'll own it) toward X type of plots. But she was the author; she knew what she wanted to do with her book best; she may well have been right about the whole thing, or as right as one can declare anything when all reading is subjective; and I admired her devotion to her vision, even if I was unable to share it. We ended up mutually agreeing to part ways, with the sincerest good wishes on each side -- which nonetheless left me sad and confused about my inability to help her get where she wanted to go, even as I was relieved and glad that she could now find someone else to do that as I could not. Sometimes we just have to accept that the obstinate, not entirely reasonable opinions are what make us who we are, and live with that, with the gains and losses that follow. And then again remember the "opinions are opinions" thing.

15. I don't know if this kind of separation will work in the same-sex marriage debate, or any of the other religiously based conflicts that roil America, except that I feel sure Brian Brown will never go to Dan Savage's place ever again.

16. And sometimes the monkey brain is necessary and can be used for good. Rep. Todd Akin was simply flat-out wrong about his medical facts, and oh my goodness did he need to be called on them (and now voted out so he can't implement the thinking behind them). When we encounter something that activates the monkey brain, we need to feel and conserve the energy from that; take a deep breath; remember we are never, ever in possession of perfect knowledge or righteousness; weigh the supposed offense against our truths and our principles and our long-term ends (time spent objecting to a blog post can be better spent on supporting an election); and then fight as hard and reasonably and honorably and passionately as we can.

17. I need a conclusion here, because otherwise I can ramble all night and continue to contradict myself into oblivion. Oh, here's one: conclusion.

Published on August 27, 2012 20:22