Laird Barron's Blog, page 44

November 2, 2013

Theme Song of a Heavy

I’m writing a crime novel about a guy with a lot of evil in his heart. If he had a theme song, this is what they’d play.

Clownette

“Clownette” is a story by Terry Dowling that originally appeared in SCI FICTION. After the ezine went under, a few of us wrote appreciations in honor of editor Ellen Datlow’s wonderful six year run. There are good places for fiction on the web, but nothing has replaced SCI FICTION.

Appreciation of Terry Dowling’s Clownette

Terry Dowling knows the heart of fear hasn’t strayed far from the caves and he understands the raw, ineluctable fascination of a campfire tale. He is conversant with its rules and rituals-—Did you hear the one about the guy, this salesman, who couldn’t get a room at his regular hotel? So the clerk says, “Hey, you could stay in this one room we got in back. We’ll give you our special rate . . .”

A proper campfire tale imparts a moral, a lesson, some bit of unhappy wisdom often gained at prohibitive expense. A proper campfire tale never concerns anybody special; it’s always about a couple of kids necking on Blueberry Hill, or the guy who ignores his fuel gauge until his car dies on a bleak stretch of country road at night, or, as in this piece, the hapless salesman who settles for the only room at the inn. The protagonist could’ve been one of us. Next time he might be.

In “Clownette,” Bob Jackson, harried businessman and routine traveler, discovers there are no vacancies at his regular hotel, the Macklin, except for 516-—the room employees half-jokingly refer to as the Clownette:

And this time, for maybe the eighteenth, nineteenth time in six years, it was a full house and the Clownette or nothing.

516 is an overflow room, a room few want because of the “rush of weird” that greets one at the threshold, an electric charge, a brief, ominous sensation impelling the visitor to flee. But-—the Clownette or nothing? No other hotel in the entire city? Surely Jackson’s predicament is an exaggeration, a contrivance. Not so; Dowling has deftly and elegantly foreshadowed the compulsion of morbid curiosity as it afflicts the human mind and how it drives poor, foolish Bob Jackson to tamper with things best left undisturbed.

The “rush of weird” isn’t the main attraction, however. No, that would fall to the bizarre stain on the wall, a large discoloration that bleeds through any paint job. They say covering it up with furniture is equally fruitless, because . . . because the stain moves, you see. It creeps and seeps and reaffirms itself upon the surface of the dresser, the painting, or whatever has been artfully placed to block its unsightly presence from the clientele. And it gets worse. At night the stain transforms in a most peculiar and disturbing fashion:

“You get to see the face, the ‘Motley,’ the Macklin Hotel’s very own Shroud of Turin right there in the wall.”

The Motley. Ah, and now we come to Mr. Jackson’s motive for accepting these “lesser” accommodations: here is an infrequent opportunity to rendezvous with his friendly nemesis, the leering Motley. He’s heard the legends regarding its mysterious manifestations and decided to test them for himself. This time around he’s determined to play a little game with the Man in the Wall. God help him. Jackson is a bug trapped in the honeyed embrace of a sundew, drawn to doom by his own design.

Most powerfully, Dowling in his light-as-air characterization of anonymous Bob Jackson has drawn a perfect cipher for the reader to experience the inexplicable and utterly sinister phenomena in room 516—-for this story isn’t about Jackson, it’s about any of us who have ever been tempted to go against better judgment, to accept a dare, or delve into the secret and dark places that exist in the gaps of our everyday lives. It is and has ever been contrary to human nature to leave well enough alone. Dowling quite obviously understands this fact and employs it to devastating effect.

“Clownette” is a brief, suffocating paean to fear. Terry Dowling has given us a dose of horror in its purest form-—at once cautionary and dreadful. Curiosity is the death of cats, as they say. However, death is the least of what curiosity can inflict upon the unwary and the unwise, and by the time Bob Jackson’s stay-—our stay-—in the Macklin Hotel has ended, that bitter lesson will be all too clear.

–Laird Barron, Olympia, WA 2006

November 1, 2013

Vlad & Jack

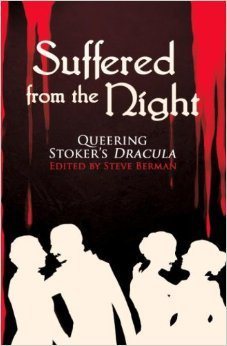

My new horror stories are set in, or strongly reference, Alaska. Steve Berman took one called “Ardor” for his new anthology Suffered From The Night: Queering Stoker’s Dracula.

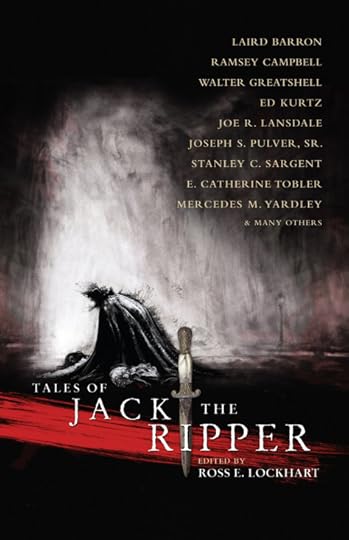

Another was recently published by Ross Lockhart for Tales of Jack the Ripper. Stefan Dziemianzowicz gives the anthology a terrific review in LOCUS. He gets what’s going down in my contribution, “Termination Dust.”

October 31, 2013

Happy All Hallows Eve

October 30, 2013

Bonus Post: Joshi versus The Beautiful Thing

Angel

There’s about 36 hours left to grab The Beautiful Thing That Awaits Us All on Kindle for the fire sale price of 1.99. Thanks again to everybody who picked it up so far. It has been numero uno in its category off and on the entire month and that’s a big deal.

I’ll leave you with one of my favorites by Massive Attack and currently on the theme song track for my in-progress crime novel:

October 29, 2013

Peter Straub

Last week I was in New York with John Langan for a reading. We spent much of the day with Peter Straub at his place on the Upper West Side. Peter had extended the invitation a while back and we finally had a chance to get into the city.

His work meant a lot to me during my early teens when I discovered Shadowland, Ghost Story, Floating Dragon, and The Talisman. Back then, I envisioned myself an author of space opera and epic fantasy; my journeys within Peter Straub’s universe were purely for escape from a bad childhood. Little did I know what a profound and lifelong impression his words would have. He’s one of the touchstones I return to when lost or stymied–I ask myself how he’d get a character from one scene to the next, how he’d handle a tricky narrative transition, or an act of transformative violence, or any of a dozen similar technical propositions. He and a handful of others have served as exemplars of the trade through their works. I’ve never needed a workshop or how-to manual or a magic bullet. Because I’ve always had these things in the novels and collections of Peter Straub, TED Klein, Roger Zelazny, and their colleagues.

Peter is a gracious man. I knew this from our interactions at various conventions over the last seven or eight years. He welcomed us into his home, a five story brownstone, laden with enough books to stock a couple of public libraries. We talked shop, confirming my estimation that the man keeps abreast of literary happenings–his to-read stack loomed over the kitchen table. He’s on top of the contemporary scene and we had a nice discussion regarding our admiration for the likes of Aimee Bender, Dan Chaon, Ben Percy, and Brian Evenson, among a slew of others. I might have turned him on to the brilliance of Stephen Graham Jones. If so, the mission was a total success.

Later, he took us to lunch at a classy little neighborhood bistro. After lunch came a leisurely tour of the house, which, due to its scope and dimensions, merely scratched the surface. Peter is a collector of fine things, especially books, and John was in awe over the shelf of of various Raymond Chandler tomes, all first editions. We wound up on the top floor…After thirty-plus years of admiring Peter Straub’s work, it was an odd sensation to stand in the middle of his office where all the black magic happens.

When it came time to depart, Peter gifted me a signed collector’s edition of his novella The General’s Wife, one of the few things of his I haven’t read. Then John and I were heading for yet another subway to meet up with my agent in preparation (drinking booze) for the reading. I had a terrific afternoon. One of those times you hope for when you’re a kid learning to write, hoping for a career in the trade, possessed of some nebulous notion of what that all means to be a successful author. Thanks to Peter’s graciousness, it was exactly the way my thirteen-year-old self imagined the scene. That’s pretty damned special.

October 28, 2013

Phase IV

Old news, but interesting. Ant supercolonies are taking over the world as Livia Llewellyn and others have predicted for years.

As a matter of fact, the prophetic Phase IV sums it all up.

October 26, 2013

Watch This: Witchy Woman

October 25, 2013

Stalking Through the Jungles of the Night

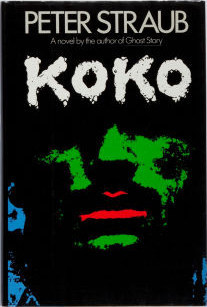

In honor of a recent visit with Peter Straub, here is an afterword I wrote for the Centipede Press special addition of Koko.

Koko: Stalking Through the Jungles of Night

By Laird Barron

Peter Straub’s epic Koko is an astonishing account of a descent into lunacy and depravity. A black odyssey on par with Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian and Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, it is a classic of horror literature and one of the greatest treatments of the serial killer genre. The narrative unfolds like a peculiarly lucid nightmare: the journey to find the murderous Koko, a specter of their past, carries four war veterans from the hard shine of New York to the lush jungles of Asia, and in a real sense, the lower regions of Hell. Straub was well along the path to fame with previous novels, but this is the one that cemented his name in American letters.

Koko originally appeared in 1988, thirteen years after the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War. A literary thriller with a sublime undercurrent of the occult, it arrived at a moment of American history when our society was slowly gaining a measure of circumspection regarding the war and those who were called to arms. A fascinating and important book in its own right, the experience of Koko is enriched if one considers its context and alignment within Straub’s body of work.

The first movement of Straub’s writing career is characterized by big, sprawling novels: Ghost Story, Shadowland, and Floating Dragon, and any discussion of Koko is a discussion of these foundational novels. Ghost Story, in retrospect, the most obvious signal of his intensifying fascination with themes of violence and corruption, and a clear analogue to Koko, follows a small fraternity of men cursed by a misdeed from their collective history, and a sinister figure who has returned to exact revenge decades in the making. The protagonists are individuals who bear hidden scars and carry secret, unimaginable burdens. The transformative moment in Ghost Storyrelies not so much upon the shocking revelation of the accidental killing of Eva Galli, a demon in human form, by the members of the Chowder Society, but rather the psychological violation this creature inflicts upon these right and proper souls with its hatefully wanton attack in the parlor. This detail is important because that profoundly affecting moment of despoliation is echoed, albeit under wildly different circumstances, in Koko when the characters and their platoon endure a horrifically nebulous ordeal while serving in Vietnam. Both instances are the prime movers that set dominos tumbling, and in both novels, our heroes are altered forever.

Thus is demonstrated a recurring theme central to Straub’s canon: innocence seared away, the shattering of the naïve world view of callow youth, the dread of a fate worse than death. He examines time and again the seepage of evil, supernatural and otherwise, into previously blameless lives, and how this defilement is often abetted by the complicity of the victims themselves. He pries at the phenomena of dogged camaraderie and the notion men in groups reinforce the best, and worst, qualities of one another. Perhaps most chillingly, he reminds us that for all our friends, we each die alone.

Koko, revisits the formative ideas of Ghost Story, and amplifies and refines them. Straub again presents us with an association of old comrades assembled to confront an unspeakable nemesis, and the dark act that may have spawned him. Koko, however, demonstrates a pronounced shift in Straub’s methods, a coalescence of tropes and techniques into something more muscular, more stylistically compact. His focus sharpens like a laser. Koko is an ambitious work, the opening shot in the second movement of his career arc. The motifs of brotherhood and honor, duty and dereliction, and the reduction of that great national tragedy of the Vietnam War to an intimate scale, imbue the novel with power and resonance. There are no demons here. Straub isn’t preoccupied with the intrusion of supernatural forces, but rather the darkness existent in the human heart, the excruciating banality of true evil. There is no insulation from this brand of evil, the effects of which we routinely witness in the news and on the streets, and like as not try to seal away by locking a door or changing the channel. Koko doesn’t flinch from these truths, and it doesn’t let the reader off the hook with a cardboard monster.

The novel is stylistically impressive. Straub plays his notes like a jazz pianist — tie loose, scotch close to one elbow, hands rambling across the keyboard. He excels at the slow burn, the relentless accretion of minor details that lead us through dark and winding valleys unto the ultimate, and inevitable, revelation. Much like his contemporary, T.E.D. Klein, another American master of the cerebral and elegantly understated horror story, Straub immerses the reader in a world as grounded as our own. He employs the prosaic, ubiquitous elements of everyday life to establish verisimilitude.

The cast of Koko exemplifies a naturalistic approach. His characters are not action stars, or superhuman sleuths. The portraits of Michael Poole, Harry Beevers, Conor Linklater, and Tina Pumo, are harrowing in the depiction of the acute nature of their suffering. These characters are damaged goods; men isolated by terrible war experiences. Their social estrangement is exacerbated by the bond they share as former soldiers who’ve been through the fire; a bond that sets them apart from regular society and chains them to a dark and bloody past. The emotional fallout is rendered all the more striking by Straub’s surgically precise exposition. The coldness of the world, cultural apathy, and institutional violence are conveyed with ruthless simplicity, a spare, yet elegant recitation of fact.

Of course, lurking in the background is the fifth man, the lunatic stalker who serves as the living shadow of them all. Straub’s titular villain remains the axis upon which the novel depends, and a singular achievement rivaling McCarthy’s Judge Holden and Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter. Maniacal and savage in pursuit of his ends, yet perversely melancholic and dutiful, Koko embodies the tragic dichotomy of a civilized people called upon to let blood in the name of peace, and the razor wire that divides love and hate, memory and loss. He is the wormy heart beating in the darkness, the distillation of every pent fear, every murmured recrimination, and every guilty conscience. Koko is the ghost who has haunted our society for three and a half decades.

Laird Barron

April 20, 2009 Olympia, WA