Ash Maurya's Blog

June 16, 2016

How to Achieve Breakthrough by Embracing Constraints

The Audi race team had the goal of winning the prestigious Le Mans race. Both their closest competitors, BMW and Mercedes, had won the race before which made the goal particularly worthy of pursuing.

The obvious way to win a race is by building a faster car. However, building a significantly faster car is non-trivial. The chief engineer at Audi instead posed a different question to his team:

“How can we win Le Mans if our car cannot go faster than anyone else’s”?

Audi won Le Mans that year. Can you guess how?

Constraints Create Space for Innovation

They won the race, not by building a faster car, but a more efficient car. The Le Mans is a grueling twenty four hours race. During that time, cars have to be refueled multiple times.

By putting diesel technology into their race cars, Audi reduced the number of pitstops their car had to make which was the edge they needed to win.

Constraints Are Gifts

The word “constraint” evokes a negative feeling in most people.

Constraint (noun): something that limits or restricts someone or something.

When people face a constraint, they either fall victim and revise their ambition downward, or confront the constraint head-on and look for ways to lift it.

From a systems perspective, however, constraints are neither good nor bad. Every system always has one and correctly identifying that single constraint holds the key to practicing “right action, right time”.

The biggest results come from just a few key actions. The challenge, of course, is identifying where to focus and more importantly what not to do.

This mind shift is the first step towards breaking constraints.

Constraints Force Action

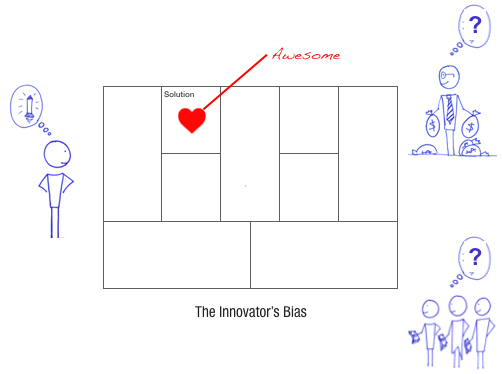

Entrepreneurs with an “awesome” idea encounter this same dilemma of limited constraints. When hit with a promising new idea, they either rush towards building out their solution or rush towards finding people with bags of money — so they can acquire the resources needed to rush towards building out their solution.

This is a backward approach. Many entrepreneurs fall victim to limited resources and never move their idea forward. Others that manage to brute-force their idea into a product often find that they have built something nobody wants.

The number one reason why new products fail is not a failure to build what we set out to build, but a failure to find the right customers and markets for our products. We simply waste needless time, money, and effort building the wrong product.

Here’s the kicker: You don’t need to first build a product to uncover what customers want.

As with the earlier example, entrepreneurs need to also embrace their starting constraints and ask themselves the following propelling questions:

How do I build what people want without a complete team?

How do I build what people want without money?

How do I build what people want without a lot of time?

Even if you don’t have apparent resource constraints (as in a large company), I find that you still need to constrain your resources as a necessary condition for driving breakthrough innovation.

So how do you build what people want with all these constraints?

Here’s the key insight: Starting constraints in innovation aren’t internal constraints but external (market) constraints.

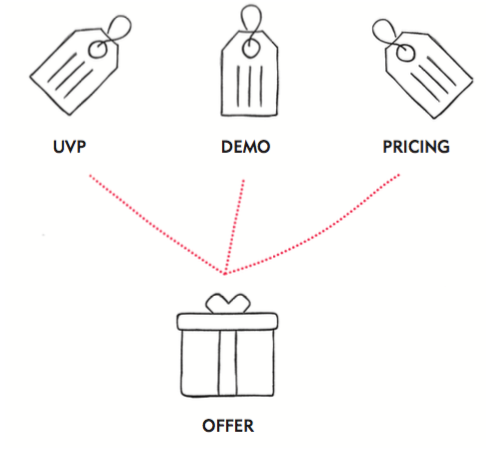

Until you can demonstrate sufficient market demand for your idea, there is no point in building out your solution. Customer don’t care about your solution but your offer. Build that instead. You don’t need lots of time, money, or people to test an offer.

An offer is made up of three things: a unique value proposition (your promise), a demo (how you achieve the promise), and a pricing model (what you want in exchange). Starting with an offer, allows you to front load your riskiest customer and market assumptions and puts you on the right starting path for building what customers want.

The journey from there is not a straight shot. There will be unexpected twists and many more distractions along the way. The key to reaching your destination is continually staying focused on the right constraints and first asking:

“How can I achieve the goal without additional resources?

=======

This post is adapted from Ash Maurya’s new book, SCALING LEAN: Mastering the Key Metrics for Startup Growth.

June 5, 2016

The Art of the Scientist

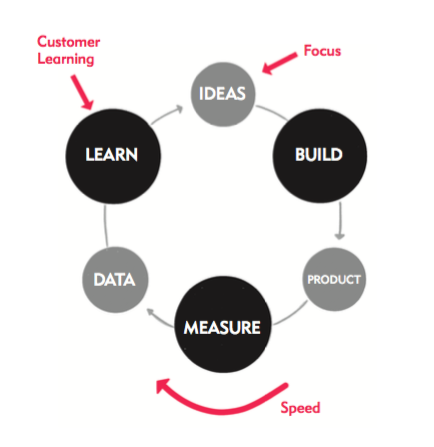

After the introduction of the scientific method, there was a marked increase in the pace of breakthrough discoveries. Both science and entrepreneurship operate under conditions of extreme uncertainty, so the thinking goes that the adoption of some entrepreneurial method might do for business innovation what the scientific method did for scientific discoveries: dramatically accelerate the pace. This is the core message of the Lean Startup methodology.

The closest equivalent to a scientific experiment in innovation is a cycle around the Build-Measure-Learn validated learning loop.

However, simply running more experiments is not enough. More cycles around the build-measure-learn loop do not automatically lead to new insights. Many experiments simply invalidate a bad idea and leave you stuck.

So how then do you set yourself up for breakthrough? The answer lies in a deeper understanding of how true science is done.

The Scientific Method in a Nutshell

In addition to his contributions to the development of quantum electrodynamics, which won him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1965, Richard Feynman was recognized as a keen popularizer of the scientific method. He described the scientific method using the following three-step process:

Notice that we don’t start with experiments. Rather we start by guessing a new law or a new theory. Then we compute the consequences of our guess. Finally, we compare those computations with experiments or observed experiences.

Guesses Come From Models

Albert Einstein was one of the most celebrated scientists of the twentieth century. But he formulated the theory of relativity without running a single empirical experiment. In fact, while Einstein was a student at the Zurich Polytechnic Institute, he was advised by a professor there to get out of the profession because he wasn’t good at devising experiments.

Einstein attributed his breakthrough insights not just to his mathematical and scientific prowess but to his simple mental models. These models were abstracted from the shapes and functions of everyday objects like trains, clocks, and elevators, and they helped him run hundreds of thought experiments. (You might remember some of these from high school physics.)

As I studied other scientists, I found the same repeating pattern: Scientists first build a model. Then they use experiments to validate (or invalidate) their model.

Entrepreneurs need models too.

Like Einstein’s models of the universe, we need simple abstractions to help deconstruct the complex problems of building a repeatable and scalable business.

My last book, Running Lean introduced one such model, the Lean Canvas, that can help you deconstruct a complex business idea into a business model. My next book, Scaling Lean, introduces two additional complementary models: a traction model and a customer factory model — that allow you to effectively measure and communicate the output of a working business model.

Guesses Can Only Be Proven Wrong

Another key concept from the scientific method is that guesses or theories can never be proven right — they can only be proven wrong. This is the concept of falsifiability. Many people don’t understand this. They think science is about running experiments to validate our guesses. But you can never run enough experiments to completely validate any guess. All it takes is a single experiment to completely invalidate a guess. In other words, it is possible to formulate a guess, build a model, and run experiments that validate your model. But over time, you might run a wider range of experiments, and gather additional experiences, that no longer agree with your theory and which then prove your theory wrong.

This is is what happened to Newton’s law for the motion of planets. He guessed the law of gravitation and computed the consequences for the solar system, which matched up with experiments for several hundred years until a slight anomaly was discovered with the motion of Mercury. During all that time, the theory hadn’t been proven right, but in the absence of being proven wrong, it was taken to be temporarily right.

This is why true science is hard. The good news is that entrepreneurship is less hard. Entrepreneurs aren’t searching for perpetual truths but temporal truths. Our job is to wield these guesses into strategies or growth hacks that make our business model work for some slice of time. These strategies are considered temporarily validated only if they move the business model goal forward. Furthermore, all growth strategies eventually reach saturation when they need to be replaced by new ones.

Even within our current business model trajectory, our “previously validated” guesses can quickly come under question in the face of continuous innovation.

If you aren’t constantly trying to disrupt yourself, i.e., prove your business model wrong, someone else will.

Breakthrough Comes From Wrong Guesses

Can you find the common theme across these discoveries: Penicillin, microwave, X-ray, gunpowder, plastics, and vulcanized rubber?

Yes, they were all accidental discoveries. But because they were accidental, it’s easy to dismiss them as lucky breaks. However, there was more than luck at play. All these discoveries started as failed experiments.

In each of these cases, the inventors were seeking a specific outcome and instead got a different outcome. But instead of throwing away their “failed” experiments, they did something very different from most people: they asked why.

Innovation experiments are no different. Achieving breakthrough, then, is less about luck and more about a rigorous search. The reason the hockey-stick trajectory has a long at portion in the beginning is not because the founders are lazy and not working hard, but because before you can find a business model that works, you have to go through lots of stuff that doesn’t.

Breakthrough insights are often hidden within failed experiments.

Most entrepreneurs, however, run away from failure. At the first sign of failure, they rush to course correct without taking the requisite time to dig deeper and get to the root cause of the failure. In the Lean Startup methodology, the term “pivot” is often used to justify this kind of course correction.

But this, of course, is a misuse of the term:

A pivot not grounded in learning is simply a disguised “see what sticks” strategy.

The key to breakthrough isn’t running away from failure but, like the inventors above, digging in your heels and asking why. The “fail fast” meme is commonly used to reinforce this sentiment. But I’ve found that the taboo of failure runs so deep (everywhere except maybe in Silicon Valley) that “failing fast” is not enough to get people to accept failure as a prerequisite to achieving breakthrough. You need to completely remove the word “failure” from your vocabulary.

There is no such thing as a failed experiment, only experiments with unexpected outcomes.

—BUCKMINSTER FULLER

November 26, 2015

September 24, 2015

It is better to be prescriptive and wrong, than vague and right

The worst possible answer you can get to a question is: “It depends.”

It depends is often a cop out for fear of being proven wrong.

It is better to be prescriptive and wrong, than vague and right.

Getting a prescriptive answer leads to action which leads to learning.

An open ended answer simply extends action paralysis.

It depends is often a cop out for fear of not having enough information.

You need to come to terms that we never have perfect information,

but you have to make a decision and move forward anyway.

Next time someone tells you: “It depends”.

Ask them: “Depends on what?”

Then give them what they need so they push towards a clear action driven answer.

September 21, 2015

Paid Channel or Partner Channel

Got an interesting question on tradeoffs between pursuing

a paid channel (e.g. PPC) vs. partner channel (e.g. JV).

On the surface PPC may seem more expensive than partners,

but it’s not.

Partners trade on their social capital

which is often more valuable to them right now,

than your future promise of money.

People who do this professionally (like JVs) have to manage a tight promotions calendar

and need to ensure high quality so they don’t burn out their audience.

If you go to a potential partner with an untested offer,

you are doing both yourself and them a huge disservice.

Put yourself in their shoes:

Would you take on the work of figuring out the right problem/solution fit

for someone else’s product – one you may not understand that well,

know if it really works, or be able to change?

It is far more effective for you to first get an offer that converts – even at small scale.

Paid channels help you do this on your own time and budget.

Then use this learning and conversion rate as evidence of traction

to first get 1-2 partners to amplify your reach.

If it works, step on the gas, and level up from there.

September 18, 2015

Users are Work-In-Progress

The job of every business is to build a customer factory

that takes in unaware visitors as raw materials and

turns them into happy customers.

In this analogy, users represent work-in-progress inventory,

while customers represent finished products.

Excess inventory is a form of waste.

The goal of a system is to maximize throughput

while minimizing inventory.

The same is true of your customer factory.

September 17, 2015

Avoid Baseless Arguments

An argument is a series of statements typically used to persuade someone of something or to present reasons for accepting a conclusion.

– Wikipedia

Arguments can be deductive or inductive.

Deductive arguments are based on premises

that aim to guarantee the truth of the conclusion.

While inductive arguments only support the probability of something being true.

Arguing from first-principles, as is done in science, are deductive arguments.

Most other arguments tend to fall in the latter category

because the premises are not falsifiable

or don’t have sufficient certainty.

We tend to rely on the art of

rhetoric to make a case, or

analogy to defend a case, or

just plain will to force a case.

I have argued with all these instruments in the past,

and while I may have won the argument,

I didn’t always win on the goal.

You can’t force the goal.

It’s much more important to achieve the right goal together

than be pseudo-right together or

absolutely right alone.

September 15, 2015

Better Entrepreneurs

I threw out the word “better” entrepreneur the other day

which I thought I’d clarify.

Some people choose to measure entrepreneurs

by the size of their exit or their net worth,

but that’s too shallow a definition.

There has to be a why beyond making money.

I liken the entrepreneurial journey to one of self-discovery with 3 stages:

1. The Artist Stage

It starts with a passion for creating something bold and different.

This is when you hone your product chops.

2. The Survival Stage

Artists need to be able to sell their art or they’ll starve.

This is when you hone your marketing chops.

3. The Transformation Stage

You put it all together and seek a why beyond money.

This is when you define your purpose.

In my view, “better” entrepreneurs make it through all three stages,

and they do it faster than their peers.

September 14, 2015

How to go from 50 customers to 500 customers

Got an interesting question the other day on

when to transition from high touch customer development to all out online marketing.

How to go from 50 customers to 500 customers?

First, you don’t 10X by deciding to flick a switch.

Rather think of it a series of 2X leveling-up strategies.

Establishing repeatability is a prerequisite to pursuing growth.

If you can’t repeatably sign-up dozens of customers,

no amount of online marketing is going to help you.

It’s just a recipe for pouring your money down the drain.

If you do have a repeatable sales process, you are ready for leveling up.

Here’s the 3 step process:

1. Identify the least scalable part of your customer acquisition process – the constraint.

2. Then systematically work towards breaking this constraint.

3. Rinse and repeat.

September 12, 2015

Disruptive Evolution

I am currently reading a fascinating book by Yuval Harari: Sapiens – A brief history of humankind.

Here’s are some particular excerpts that caught my attention:

For millions of years, humans hunted smaller creatures and gathered what they could, all the while being hunted by larger predators. Only in the last 100,000 years – with the rise of Homo sapiens – did man jump to the top of the food chain.

Whether Sapiens are to blame or not, no sooner had they arrived at a new location than the native population became extinct.

This spectacular leap from the middle to the top has enormous consequences. Other animals at the top of the pyramid, such as lions and sharks, evolved into that position very gradually, over millions of years. This enabled the ecosystem to develop checks and balances that prevent lions and sharks from wreaking too much havoc. As lions became deadlier, so gazelles evolved to run faster, hyenas to cooperate better, and rhinoceroses to be more bad-tempered. In contrast, humankind ascended to the top so quickly that the ecosystem was not given time adjust.

How did we – a weaker species in the Homo genus, on the verge of near extinction, not only rise to the top of our family, but to the top of the ecosystem?

The answer is through many seemingly small differences that ultimately mattered.

Lots of parallels to be drawn between evolution and innovation.

Pick up a copy.

Credits: Yuval Harari, Sapiens