Robert I. Sutton's Blog, page 4

August 21, 2013

Dysfunctional Competition, the Knowing-Doing Gap, and Sears Holdings

A compelling and instructive story on Sears Holdings appeared in BusinessWeek last month -- they own Sears stores, Kmart, Land's End and a host of other brands such as Craftsman tools, Kenmore appliances, and DieHard batteries. It is written by Mina Kimes and provides a textbook example of how, when people in a company are pitted against each other -- rather than pressed and paid to support the greater good -- that cooperation evaporates. People treat insiders (rather than outsiders) as enemies. And even when they know what needs to be done for the effectiveness of the organization as a whole, they often don't do it -- because helping others (or contributing to the greater good) undermines their income, stature, and job security.

Jeff Pfeffer and I wrote about this disease in some detail in The Knowing Doing Gap in 2000 and in related articles and posts based on the book, for example, here, here, and here. It has been over a decade since we focused on this problem, but if anything, it has become worse in many companies -- as the Sears story shows. Kimes' detailed article provides many examples of the problems caused by the Sears structure and incentives, where CEO Eddie Lampert has split the company into some 30 warring units, each with "its own president, chief marketing officer, board

of directors, and, most important, its own profit-and-loss statement."

Lampert defends this structure as "decentralized," but that confuses a structure where individual units have autonomy to act largely as the please with one where there is no incentive (or worse, a disincentive) to support the company's overall performance. Google, for example, is quite decentralized, but there have always been both cultural and financial pressures to do what is best for the company as a whole. Even within the famously competitive and decentralized General Electric, there have been incentives for cooperation for decades and selfish "cowboys" who don't support colleagues and the culture have been banished from the company.

In contrast, let's take a rather astounding example from the Sears story:

"At the beginning of 2010, Lampert hired 20-year Wal-Mart Stores veteran Jim Haworth to run Sears and Kmart stores as president of

retail services. Haworth, an affable, mustachioed Midwesterner, saw

immediately that Kmart’s food and drugs were more expensive than those

at Walmart and Target.

So he met with a few top executives, including Chief Financial Officer

Mike Collins and operations chief Scott Freidheim, to look into

discounting goods such as milk and soda.

That summer the group

asked the company’s internal research team to study the idea, according

to eight former executives. The researchers came back with a proposal:

Cut prices at several dozen Kmarts across the country, bringing the cost

of items to within 5 percent of Walmart’s. The business unit presidents

agreed. But when Haworth’s group tried to get them to cough up

$2 million to fund the project, no one was willing to sacrifice business

operating profits to increase traffic."

The reason, according to the story, that no President was willing to cough up any funds was that cutting into their businesses operating profit would, in turn, reduce their bonuses. The parent company refused to fund the effort as well and the key executives involved in pressing for the proposal are no longer with Sears. In short, it is a nearly perfect example of how -- even though everyone knows the right thing to do for the collective good -- no one does it because they live in zero-sum, I win and you lose, world. As the article shows, this mindset can create some mighty ugly scenes:

"The bloodiest battles took place in the marketing meetings, where

different units sent their CMOs to fight for space in the weekly

circular. These sessions would often degenerate into screaming matches.

Marketing chiefs would argue to the point of exhaustion. The result,

former executives say, was a “Frankenstein” circular with incoherent

product combinations (think screwdrivers being advertised next to

lingerie)."

This me me me mindset might work in situations where there is no need for collaboration, information sharing, or even pooled resources. But it doesn't work when people and units depend on each other to succeed.

I also want to emphasize -- despite some suggestion from Lampert and others that cooperation is a form of evil socialism -- that many companies have cultures and incentives that generate both competition and collaboration simultaneously (to name five widely varied organizations, McKinsey, IDEO, General Electric, Procter & Gamble, and the Men's Wearhouse all accomplish this one way or another). The trick is that star employees are defined (and trained, groomed, rewarded, and led) as those who do high quality individual work (or, for more senior people, lead top performing teams or businesses) AND who help colleagues (on their team, on different teams, and in different businesses) succeeded as well. If you don't do both consistently, you aren't a star. In such places, the competitive pressures to HELP others and the

ORGANIZATION are palpable: People compete against each other by trying

to be MORE collaborative than their colleagues. Its like a weird Jedi mind trick, but it works beautifully when done well.

While I am no fan of forced rankings (I don't believe that every organization must be doomed to have 10% to 20% defective employees, for example), when people are evaluated, or even ranked, on this dual standard, organizations perform far better than when have you a situation such as at Sears where "As the business unit leaders pursued individual profits, rivalries

broke out. Former executives say they began to bring laptops with screen

protectors to meetings so their colleagues couldn’t see what they were

doing."

In short, when I want to know if an organization rewards or punishes cooperation, the diagnostic question I ask is "Who are the superstars around here? Are they the selfish people who stomp on others on the way to the top? Or are they the people who do great work AND who use what they know to lend a helping hand to others?"

P.S. The recent structural changes at Microsoft -- long infamous for its nasty internal competition -- provide an interesting counterpoint. They are not only becoming more centralized and streamlined ala Apple, as The New York Times reports "The goal is to get thousands of employees to collaborate more closely,

to avoid some duplication and, as a result, to build their products to

work more harmoniously together." Microsoft has a long history and ingrained habits to overcome, but this strikes me as a step in the right direction.

July 15, 2013

Delta Airlines Shows How to Apologize

Please forgive my months of silence. I appreciate all the folks who have asked if I am OK (I am fine!) and who have urged me to start blogging again. You will start hearing more here about what I've been doing the last six months. The short story is that Huggy Rao and I have been working like crazy on Scaling Up Excellence, our book that will be published in early 2014. We just have a few finishing touches after putting seven years or so into this project. Then I will start talking about it -- this book has been quite an adventure and we are already talking to a lot of different groups about the main ideas.

Meanwhile, I was moved to do a post because, as we have written the book, one of the themes that has moved center stage, and I've blogged about before, is accountability: How it is a hallmark of organizations that spread and sustain excellence (and its absence of a hallmark of bad ones). This problem was especially evident in United Airlines' poor treatment of my friend's young daughter last summer. As counterpoint, a friend sent me this note of apology he got from Delta. Note I have removed his name and account number. Obviously, airlines can't control things like the weather and other systemic delays -- but when leaders step-up and do this kind of thing, it creates a lot of goodwill -- and is evidence that they are taking responsibility and trying to fix things.

Please Accept Our

Apology

Dear _____________,

On behalf of Delta Air Lines, I would like to extend my personal apology for

the inconvenience you experienced as a result of the delay of Flight DL1505

on July 06, 2013.

I am truly sorry your travel was adversely affected by our service failure.

Please know that within the industry, we have earned a solid reputation for

our commitment to operational integrity. To that end, each flight

irregularity is thoroughly reviewed to prevent a similar occurrence. I pledge

to you that we are dedicated to providing the safe, reliable transportation

you expect and deserve.

We value you as a customer and sincerely appreciate your support of Delta. To

demonstrate our commitment to service excellence, as a gesture of apology I

am adding 5,000 bonus miles to your SkyMiles account XXXXXXXXX. Please allow

three business days for the miles to appear. If you would like to verify your

mileage balance and gain access to all of our mileage redemption programs,

you may visit us at www.delta.com/skymiles.

It is our goal to provide exceptional service on every occasion, and I hope

you will provide us with an opportunity to restore your confidence. Your

support is important to Delta, our Connection carriers and our SkyTeam

partners. We look forward to your continued patronage and the privilege of

serving your air travel needs again soon.

Sincerely,

Jason Hausner

Director, Customer Care

November 26, 2012

11 Books Every Leader Should Read:Updated

I first posted this last December, but I thought that it would be fun to update it. Note I have removed two from last years list: Men and Women of the Corporation and Who Says that Elephants Can't Dance? They are both great books, but I am trying to stick to 11 books and the two new ones below edge them out. Here goes:

I was looking through the books on Amazon to find something that struck my fancy, and instead, I started thinking about the books that have taught me much about people, teams, and organizations -- while at the same time -- provide useful guidance (if sometimes only indirectly) about what it takes to lead well versus badly. The 11 books below are the result.

Most are research based, and none are a quick read (except for Orbiting the Giant Hairball). I guess this reflects my bias. I like books that have real substance beneath them. This runs counter the belief in the business book world at the moment that all books have to be both short and simple. So, if your kind of business book is The One Minute Manager (which frankly, I like too... but you can read the whole thing in 20 or 30 minutes), then you probably won't like most of these books at all.

1. The Progress Principle by Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer. A masterpiece of evidence-based management -- the strongest argument I know that "the big things are the little things."

2. Influence by Robert Cialdini the now classic book about how to persuade people to do things, how to defend against persuasion attempts, and the underlying evidence. I have been using this in class at Stanford for over 20 years, and I have had dozens of students say to me years later "I don't remember much else about the class, but I still use and think about that Cialdini book."

3.Made to Stick Chip and Dan Heath. A modern masterpiece, the definition of an instant classic. How to design ideas that people will remember and act on. I still look at it a couple times a month and I buy two or three copies at a time because people are always borrowing it from me. I often tell them to keep it because they rarely give it back anyway.

4. Thinking, Fast and Slow Daniel Kahneman. Even though the guy won the Nobel Prize, this book is surprisingly readable. A book about how we humans really think, and although it isn't designed to do this, Kahneman also shows how much of the stuff you read in the business press is crap.

5. Collaboration by Morten Hansen. He has that hot bestseller now with Jim Collins called Great By Choice, which I need to read. This is a book I have read three times and is -- by far -- the best book ever written about what it takes to build an organization where people share information, cooperate, and help each other succeed.

6. Orbiting the Giant Hairball by Gordon MacKenzie. It is hard to explain, sort of like trying to tell a stranger about rock and roll as the old song goes. But it is the best creativity book ever written, possibly the business book related to business ever written. Gordon's voice and love creativity and self-expression -- and how to make it happen despite the obstacles that unwittingly heartless organizations put in the way -- make this book a joy.

7. The Pixar Touch by David Price. After reading this book, my main conclusion was that it seems impossible that Pixar exists. Read how Ed Catmull along with other amazing characters-- after amazing setbacks, weird moments, and one strange twist after another -- realized Ed's dream after working on it for decades. Ed is working on his own book right now, I can hardly wait to see that. When I think of Ed and so many others I have met at Pixar like Brad Bird, I know it is possible to be a creative person without being an asshole. In fact, at least if the gossip I keep hearing from Pixar people is true, Jobs was rarely rude or obnoxious in his dealings with people at Pixar because he knew they knew more than him -- and even he was infected by Pixar's norm of civility.

8. The Laws of Subtraction by Matthew May. This 2012 book has more great ideas about how to get rid of what you don't need and how to keep -- and add -- what you do need than any book ever written. Matt has as engaging a writing style as I have ever encountered and he uses it to teach one great principle after another, from "what isn't there can trump what is" to "doing something isn't always better than doing nothing." Then each principle is followed with five or six very short -- and well-edited pieces -- from renowned and interesting people of all kinds ranging from executives, to researchers, to artists. It is as fun and useful as non-fiction book can be and is useful for designing every part of your life, not just workplaces.

9. Leading Teams by J. Richard Hackman. When it comes to the topic of groups or teams, there is Hackman and there is everyone else. If you want a light feel good romp that isn't very evidence-based, read The Wisdom of Teams. If want to know how teams really work and what it really takes to build, sustain, and lead them from a man who has been immersed in the problem as a researcher, coach, consultant, and designer for over 40 years, this is the book for you.

10. Give and Take by Adam Grant. Adam is the hottest organizational researcher of his generation. When I read the pre-publication version, I was so blown away by how useful, important, and interesting that Give and Take was that I gave it the most enthusiastic blurb of my life: “Give and Take just might be the most important book of this

young century. As insightful and entertaining as Malcolm Gladwell at his

best, this book has profound implications for how we manage our

careers, deal with our friends and relatives, raise our children, and

design our institutions. This gem is a joy to read, and it shatters the

myth that greed is the path to success." In other words, Adam shows how and why you don't need to be a selfish asshole to succeed in this life. America -- and the world -- would be a better place if all of memorized and applied Adam's worldview.

11. The Path Between the Seas by historian David McCullough. On building the Panama Canal. This is a great story of how creativity happens at a really big scale. It is messy. Things go wrong. People get hurt. But they also triumph and do astounding things. I also like this book because it is the antidote to those who believe that great innovations all come from start-ups and little companies (although there are some wild examples of entrepreneurship in the story -- especially the French guy who designs Panama's revolution -- including a new flag and declaration of independence as I recall -- from his suite in the Waldorf Astoria in New York, and successfully sells the idea to Teddy Roosevelt ). As my Stanford colleague Jim Adams points out, the Panama Canal, the Pyramids, and putting a man on moon are just a few examples of great human innovations that were led by governments.

I would love to know of your favorites -- and if want a systematic approach to this question, don't forget The 100 Best Business Books of All Time.

P.S. Also, for self-defense, I recommend that we all read Isaacson's Steve Jobs -- I keep going places -- cocktail parties, family gatherings, talks I give and attend, and even the grocery store where people start talking about it and especially arguing about it. As I explained in Wired and Good Boss, Bad Boss I have come to believe that whatever Jobs was in life, in death he has become a Rorschach test -- we all just project our beliefs and values on him.

11 Books Every Leader Should Read:Updated for 2012

I first posted this last December, but I thought that it would be fun to update it for 2012. Note I have removed two from last years list: Men and Women of the Corporation and Who Says that Elephants Can't Dance? They are both great books, but I am trying to stick to 11 books and the two new ones below edge them out. Here goes:

I was looking through the books on Amazon to find something that struck my fancy, and instead, I started thinking about the books that have taught me much about people, teams, and organizations -- while at the same time -- provide useful guidance (if sometimes only indirectly) about what it takes to lead well versus badly. The 11 books below are the result.

Most are research based, and none are a quick read (except for Orbiting the Giant Hairball). I guess this reflects my bias. I like books that have real substance beneath them. This runs counter the belief in the business book world at the moment that all books have to be both short and simple. So, if your kind of business book is The One Minute Manager (which frankly, I like too... but you can read the whole thing in 20 or 30 minutes), then you probably won't like most of these books at all.

1. The Progress Principle by Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer. A masterpiece of evidence-based management -- the strongest argument I know that "the big things are the little things."

2. Influence by Robert Cialdini the now classic book about how to persuade people to do things, how to defend against persuasion attempts, and the underlying evidence. I have been using this in class at Stanford for over 20 years, and I have had dozens of students say to me years later "I don't remember much else about the class, but I still use and think about that Cialdini book."

3.Made to Stick Chip and Dan Heath. A modern masterpiece, the definition of an instant classic. How to design ideas that people will remember and act on. I still look at it a couple times a month and I buy two or three copies at a time because people are always borrowing it from me. I often tell them to keep it because they rarely give it back anyway.

4. Thinking, Fast and Slow Daniel Kahneman. Even though the guy won the Nobel Prize, this book is surprisingly readable. A book about how we humans really think, and although it isn't designed to do this, Kahneman also shows how much of the stuff you read in the business press is crap.

5. Collaboration by Morten Hansen. He has that hot bestseller now with Jim Collins called Great By Choice, which I need to read. This is a book I have read three times and is -- by far -- the best book ever written about what it takes to build an organization where people share information, cooperate, and help each other succeed.

6. Orbiting the Giant Hairball by Gordon MacKenzie. It is hard to explain, sort of like trying to tell a stranger about rock and roll as the old song goes. But it is the best creativity book ever written, possibly the business book related to business ever written. Gordon's voice and love creativity and self-expression -- and how to make it happen despite the obstacles that unwittingly heartless organizations put in the way -- make this book a joy.

7. The Pixar Touch by David Price. After reading this book, my main conclusion was that it seems impossible that Pixar exists. Read how Ed Catmull along with other amazing characters-- after amazing setbacks, weird moments, and one strange twist after another -- realized Ed's dream after working on it for decades. Ed is working on his own book right now, I can hardly wait to see that. When I think of Ed and so many others I have met at Pixar like Brad Bird, I know it is possible to be a creative person without being an asshole. In fact, at least if the gossip I keep hearing from Pixar people is true, Jobs was rarely rude or obnoxious in his dealings with people at Pixar because he knew they knew more than him -- and even he was infected by Pixar's norm of civility.

8. The Laws of Subtraction by Matthew May. This 2012 book has more great ideas about how to get rid of what you don't need and how to keep -- and add -- what you do need than any book ever written. Matt has as engaging a writing style as I have ever encountered and he uses it to teach one great principle after another, from "what isn't there can trump what is" to "doing something isn't always better than doing nothing." Then each principle is followed with five or six very short -- and well-edited pieces -- from renowned and interesting people of all kinds ranging from executives, to researchers, to artists. It is as fun and useful as non-fiction book can be and is useful for designing every part of your life, not just workplaces.

9. Leading Teams by J. Richard Hackman. When it comes to the topic of groups or teams, there is Hackman and there is everyone else. If you want a light feel good romp that isn't very evidence-based, read The Wisdom of Teams. If want to know how teams really work and what it really takes to build, sustain, and lead them from a man who has been immersed in the problem as a researcher, coach, consultant, and designer for over 40 years, this is the book for you.

10. Give and Take by Adam Grant. This book won't be out for a few months, but you should pre-order it so you don't forget. Adam is the hottest organizational researcher of his generation. When I read the pre-publication version, I was so blown away by how useful, important, and interesting that Give and Take was that I gave it the most enthusiastic blurb of my life: “Give and Take just might be the most important book of this

young century. As insightful and entertaining as Malcolm Gladwell at his

best, this book has profound implications for how we manage our

careers, deal with our friends and relatives, raise our children, and

design our institutions. This gem is a joy to read, and it shatters the

myth that greed is the path to success." In other words, Adam shows how and why you don't need to be a selfish asshole to succeed in this life. America -- and the world -- would be a better place if all of memorized and applied Adam's worldview.

11. The Path Between the Seas by historian David McCullough. On building the Panama Canal. This is a great story of how creativity happens at a really big scale. It is messy. Things go wrong. People get hurt. But they also triumph and do astounding things. I also like this book because it is the antidote to those who believe that great innovations all come from start-ups and little companies (although there are some wild examples of entrepreneurship in the story -- especially the French guy who designs Panama's revolution -- including a new flag and declaration of independence as I recall -- from his suite in the Waldorf Astoria in New York, and successfully sells the idea to Teddy Roosevelt ). As my Stanford colleague Jim Adams points out, the Panama Canal, the Pyramids, and putting a man on moon are just a few examples of great human innovations that were led by governments.

I would love to know of your favorites -- and if want a systematic approach to this question, don't forget The 100 Best Business Books of All Time.

P.S. Also, for self-defense, I recommend that we all read Isaacson's Steve Jobs -- I keep going places -- cocktail parties, family gatherings, talks I give and attend, and even the grocery store where people start talking about it and especially arguing about it. As I explained in Wired and Good Boss, Bad Boss I have come to believe that whatever Jobs was in life, in death he has become a Rorschach test -- we all just project our beliefs and values on him.

November 22, 2012

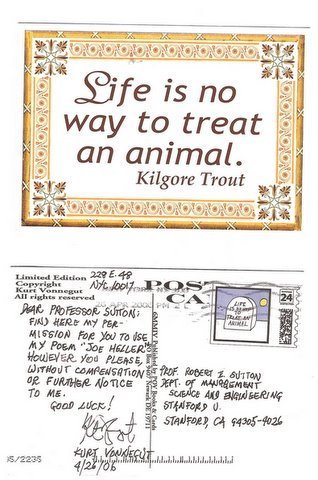

Kurt Vonnegut, Joe Heller, and a Great Thanksgiving Message

It is Thanksgiving morning here in California and I was thinking of all the good things in my life I have to be thankful for, just as I know that so many of you are thinking today. I thought it would be nice to reprint a story and poem I first posted on this blog over five years ago, on the day The No Asshole Rule was published and it was updated shortly after on the day Vonnegut died. The key part is Vonnegut's Joe Heller poem, one of the last things he published before he died. His message that reminding ourselves how much we have (rather than how much we want), that so many of us "have enough," is timeless and especially fitting for the day. Enjoy and have a happy Thanksgiving.

I just heard that Kurt Vonnegut died. I loved his books and was touched by his sweet contribution, for creating the best moment I had when writing the book. His death makes me sad to think about, but his life brings me joy. All of us die in the end, it is the living that counts -- and Vonnegut touched so many people. Here is my story.

The process of writing The No Asshole Rule entailed many fun twists and turns. But the very best thing happened when I wrote for permission to reprint a Kurt Vonnegut poem called "Joe Heller," which was published in The New Yorker. I was hoping that Vonnegut would give me permission to print it in the book, both because I love the poem (more on that later), and Vonnegut is one my heroes. His books including Slaughterhouse Five and Breakfast of Champions had a huge effect on me when I was a teenager-- both the ideas and the writing style.

I wrote some anonymous New Yorker address to ask permission to reprint the poem, and to my amazement, I received this personal reply from Vonnegut about two weeks later. Take a look at the two sides of the postcard, it not only is in Vonnegut's handwriting and gives me permission to use it "however you please without compensation or further notice to me," the entire thing is designed by Vonnegut (and I suspect his wife helped, as she is a designer). "Life is No Way to Treat an Animal" is one of the famous sayings from his character Kilgore Trout -- even the stamp is custom. It is one of my favorite things.

The poem fits well in my chapter on how to avoid catching asshole poisoning. Here is how I set it up in the book:

'If you read or watch TV programs about

business or sports, you often see the world framed as place where everyone

wants “more more more” for “me me me,” every minute in every way.

The old bumper sticker sums it up: “Whoever dies with the most toys wins.” The

potent but usually unstated message is that we are all trapped in a life-long

contest where people can never get enough money, prestige, victories, cool

stuff, beauty, or sex – and that we do want and should want more goodies than

everyone else.

This attitude fuels a quest for constant

improvement that has a big upside, leading to everything from more beautiful

athletic and artistic performances, to more elegant and functional products, to

better surgical procedures and medicines, to more effective and humane

organizations. Yet when taken too far,

this blend of constant dissatisfaction, unquenchable desires, and overbearing

competitiveness can damage your mental health. It can lead you to treat those “below” you as inferior creatures who are

worthy of your disdain and people "above" you who have more stuff and status as

objects of envy and jealousy.

Again, a bit of framing can help. Tell yourself, “I have enough.” Certainly,

some people need more than they have, as many people on earth still need a safe

place to live, enough good food to eat, and other necessities. But too many of

us are never satisfied and feel constantly slighted, even though – by objective

standards – we have all we need to live a good life. I got this idea from a lovely little poem

that Kurt Vonnegut published in The New

Yorker called “Joe Heller,” which was about the author of the renowned

World War II novel Catch 22. As you can see, the poem describes a party

that Heller and Vonnegut attended at a billionaire’s house. Heller remarks to Vonnegut that he has

something that the billionaire can never have, "The knowledge that I've

got enough." These wise words

provide a frame that can help you be at peace with yourself and to treat those

around you with affection and respect:

Joe Heller

True story, Word of Honor:

Joseph Heller, an important and funny writer

now dead,

and I were at a party given by a billionaire

on Shelter Island.

I said, "Joe, how does it make you feel

to know that our host only yesterday

may have made more money

than your novel 'Catch-22'

has earned in its entire history?"

And Joe said, "I've got something he can never have."

And I said, "What on earth could that be, Joe?"

And Joe said, "The knowledge that I've got enough."

Not bad! Rest in peace!"

--Kurt Vonnegut

The New Yorker,

May 16th, 2005

(Reprinted with Kurt Vonnegut’s permission -- see the above postcard!)

P.S. I also added another post about Vonnegut after this one that was good fun, which talked about my favorite quote.

P.P.S. The first version of this post was written on February 22nd, the day The No Asshole Rule was published. I then updated in mid-April of 2007, after I heard that Vonnegut had died. This is the third update because it seems like such a great Thanksgiving message.

November 20, 2012

An Evidence-Based Temper Tantrum Topples The Local Asshole

About 15 years ago, UC Berkeley's Barry Staw

and I had a running conversation about the conditions under which

showing anger, even having a temper tantrum, is strategic versus

something that undermines a person's reputation and influence, and for

leaders, the performance of their teams and organizations. In fact,

Barry eventually collected some amazing in-the-locker room half-time

speeches for basketball coaches that he is currently working on writing

and publishing.

I thought of those old conversations when I got

this amazing note the other day (this is the same one that inspired me

to do my last post on the Atilla the Manager cartoon):

I just discovered your work via Tom Fishburne, the Marketoonist. I had an

asshole boss until I got her fired. For 6 years I was abused and I should have

done what you say and got out as soon as I could. But you get comfortable and

used to the abuse. You even think you are successfully managing the abusers

behavior with your behavior. Ridiculous I know. I suffered everything you

mentioned including depression, anxiety and just plain unhappiness. The day I

snapped, I used the "I quit and I'm taking you down with me" tactic.

I did document the abuse even though just like every asshole situation, everyone

knew she was an abuser. In an impassioned meeting I let top management know

exactly why I was quitting, let them know they are culpable for all the mental

anquish and turnover and poor results stemming from the asshole. They probably

thought I was a madman with nothing left to lose and about to sue and defame

the company (they'd have been correct). Two hours later she was walked out. Now

the department is doing great and actually producing instead of trying to

manage the reactions of a lunatic.

I am taken with this note for

numerous reasons. For starters, I am always delighted when the victim

of an asshole finds a successful way to to fight back. I am also

pleased to see that, as happens so often, once this creep was sent

packing, people could stop spending their days trying to deal with her

antics and instead could devote their energies to doing their jobs well.

And in thinking about it in more detail -- and thinking back to those

old conversations with Barry -- I believe that showing anger was

effective in this situation for at least three reasons.

1. He was right.

This was, as the headline says, an evidence-based temper tantrum.

Although his superiors may have not been overly pleased with how he

delivered the news, he apparently had darn good evidence that this

person was an asshole and doing harm to him and his co-workers. Facts

matter, even when emotions flare.

2. His anger was a reflection of how others felt, not just his particular quirks and flaws.

This outpouring of anger and the ultimatum he gave were seen as giving

voice to how everyone who worked with this "lunatic" felt. It was his

tantrum, but it was on behalf of and gave voice to others. In such

situations, when a person is not seen as out of touch reality or crazy,

even though he may have felt or even acted like a "madman" for the

moment, the anger and refusal to give in can be very powerful. I also

suspect that, in this case, those same bosses who fired him felt he same

way about the local asshole, and his anger propelled them to take an

action they knew was the right thing to do. The notion that emotions are

contagious and propel action is quite well established in a lot of

studies (see research by Elaine Hatfield for example).

3. The was a rare tantrum.

This follows from the last point. If you are always ranting and

yelling and making threats, people aren't likely to take you

seriously. Tantrums are effective when they are seen as a rare and

justified outburst rather than a personal characteristic -- as something

that is more easily attributed to the bad situation the person is in

rather than personal weakness or style.

Please, please don't use

this fellow's success as a reason to start yelling and making threats

and all that. That is what a certified asshole would do. But -- while

such outbursts are not always the product of rational planning -- this

little episode provides instructive guidance about when expressing anger

might produce outcomes for the greater good. It also provides some

interesting hints about when it is best to try to stop outbursts from

those you are close to versus when egging them on is a reasonable thing

to do.

Finally, a big thanks to the anonymous writer of this note. I learned something from it and I hope that other do as well.

P.S. This note and post makes me think that some revision to my list of Tips for Surviving Workplace Assholes might be in order.

November 19, 2012

The Marketoonist on Attila the Manager

I got a note from a manager about this cartoon and story at the Marketoonist, which is drawn and written by Tim Fishburne -- he talks about The No Asshole Rule and the problem of brillant jerks. Check out his site, it is filled with great stuff -- like this cartoon and story about my least-favorite U.S. company, United Airlines.

P.S. I am sorry I have not been blogging much, I am hoping to turn up the volume and have a lot of things to write about, especially Matt May's new book The Laws of Subtraction. But life keeps getting in the way!

November 3, 2012

John Gardner on What a University Ought to Stand For

I spent the morning trying to catch-up on all the emails that have been piling-up and the stuff I have been collecting to read for the book we are are writing on scaling-up excellence. Huggy Rao and I spent the week as co-directors of an executive program called Customer-Focused Innovation. We had great fun and learned an enormous amount from the 65 executives who participated in blend of traditional classroom education (we call it the "clean models" part) and d.school experiential education -- project with JetBlue aimed at bringing more "humanity" to air travel for their customers (we call this the "dirty hands" part).

The program appears to be a big success (participants rated it 4.87 on a 5-point "willingness to recommend" scale). But after all those logistics and all that social ramble, I am delighted to have a quiet day.

I wasn't planning on doing a post, but I couldn't resist sharing the opening of an article by the amazing Karl Weick, one of the most imaginative people in my field.

Karl started out his 2002 British Journal of Management on "Puzzles in Organizational Learning: An Exercise in Disciplined Imagination" this way:

It is sometimes possible to explore basic questions in the university that are tough to raise in other settings. John Gardner (1968, p. 90) put it well when he said that the university stands for:

• things that are forgotten in the heat of battle

•values that get pushed aside in the rough and tumble of everyday living

• the goals we ought to be thinking about and never do

• the facts we don’t like to face

• the questions we lack the courage to ask

I read that list over and over. As you may know, the late John Gardner was one of the most thoughtful leadership "gurus" who ever lived and so much more. As a university professor, this reminded me of why my colleagues and I -- at our best, we all screw-up at times -- do certain things that annoy, surprise, and -- now and then -- actually help people. We feel obligated to take years trying to figure out the answers to questions that seem pretty simple on the surface. We study obscure things that seem trivial or at least not very important right now. We feel obligated to go with the best evidence even when we don't like answer (e.g., the recent Stanford study that shows there is little or no documented health advantage to organic food isn't something I want to hear, but it is so carefully done that I accept it as the provisionally true). We also feel obligated to ask questions of ourselves at others that can be quite unpleasant for everyone.

I think of my colleague Jeff Pfeffer in particular here, who throughout his whole career, has raised questions about everything from the overblown effects of leadership, to the ways that focusing on money turns us greedy and selfish, to his current work on how organizations and workplaces can make us ill and cause us to die premature deaths. Jeff has made a lot of people squirm people over the years, including me, but he is doing exactly what John Gardner asserted that a good professor ought to do -- seek and tell the truth, even when it is hard to take.

As has happened so many times throughout the nearly 30 years I have been a university professor, Karl Weick (with a big assist from John Gardner this time) has reminded me yet again of what is important in my line of work and the standards I should try to follow.

October 7, 2012

Brandi Chastain's Advice on Incentives and Cooperation

As regular readers of this blog may recall, my wife -- Marina Park -- is the CEO of the Girl Scouts of Northern California. It has been a busy year from Marina and her staff because it is the 100 year anniversary of the founding of the Girl Scouts and there have been many celebrations. There was an especially wild one called 100 Hundred, Fun Hundred where some 24,000 girls gathered at the Alameda County Fair Grounds to camp and engage in activities ranging from rock climbing, to scuba diving, to dancing to roakc bands. You can read about the various celebrations here on their website.

Today, I am focusing on the Forever Green Awards -- a series of dinners that have been held throughout Northern California to honor women who "have made a significant impact to sustaining the environment, economy, or community." I have been three of the eight award dinners now and have been inspired by many of these women (here is the complete list), from opera soprano Katherine Jolly, to Jane Shaw the Chairman of the Board at Intel, to Amelia Ceja -- the Owner & President Ceja Vineyards.

I heard something last week at the dinner in Menlo Park that especially caught my ear -- from none other than Brandi Chastain, the Olympic Women's Soccer gold medal winner and world champion, who still plays soccer seriously and now often works as a sports broadcaster for ABC and ESPN. Of course, Chastain we always be remembered for throwing off her jersey after scoring the winning goal at the Women's World Championships in 1999 -- in 2004 she wrote a book called "Its Not About the Bra."

The award winners at Menlo Park were each asked to describe the best advice they ever received. Brandi began by talking about her grandfather and how crucial he was to her development as a soccer player and a person. Brandi said that he had a little reward system where she was paid $1.00 for scoring a goal but $1.50 for an assist -- because, as she put it, "it is better to give than receive."

I love that on so many levels. I helped coach girls soccer teams for some years, and getting the star players to pass was often tough. And moving into the world of organizations, as Jeff Pfeffer and I have been arguing for years, too many organizations create dysfunctional internal competition by saying they want cooperation but behaving in ways that promote selfish behavior. Chastain's grandfather applied a simple principle that can be used in even the most sophisticated reward systems -- one that I have seen used to good effect in places ranging from General Electric, to IDEO, to McKinsey.

P.S. The last Forever Green Awards will be in Santa Rosa at the Paradise Ridge Winery. Click here if you want to learn more.

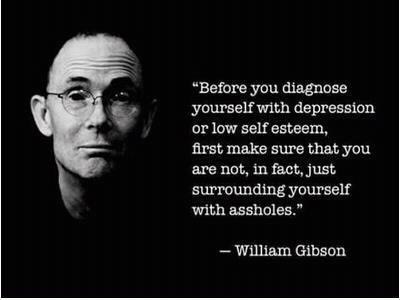

William Gibson on Assholes and the Damage Done

William Gibson is one of the most influential and out there science fiction writers of our time. Read about him here and here. He is credited with first usign the term "cyberspace" in a 1982 story and Wikipedia claims "He is also credited with predicting the rise of reality television and with establishing the conceptual foundations for the rapid growth of virtual environments such as video games and the World Wide Web." He is also credited with one of my favorite quotes "The future is already here -- it is just not very evenly distrubited.

P.S. A big thanks to Caroline for sending this to me!

Robert I. Sutton's Blog

- Robert I. Sutton's profile

- 266 followers