Robert I. Sutton's Blog, page 8

April 3, 2012

The Virtues of Standing-Up: In Meetings and Elsewhere

I was thinking back to some of the experiences I had over the last few weeks teaching classes to both Stanford students and executives, and watching some of my fellow teachers and colleagues in action. I realized that one of the hallmarks, one of the little signs I have learned to look for, is whether people are standing-up or sitting down. We all learn in school that being a "good student" means that we ought to stay in our seats and be good listeners. But I kept seeing situations where standing-up was a sign of active learning and leadership. To give you a a few examples, I noticed that when my course assistants stood up and walked around the classroom, they were more likely to be engaged by students and to create enthusiasm and energy. I noticed that student teams in my classes that stood-up when brainstorming, prototyping, or arguing over ideas seemed more energetic and engaged.

And I noticed when watching master innovation teacher and coach Perry Klebahn in action at the Stanford d. School that he hardly ever sits down for long, he is always on the prowl, walking over to members of his team to ask how things are going, to give a bit of advice, and to find out what needs to be fixed -- and is constantly walking over to to watch teams of students or executives who are working on creative tasks to see if they need a bit advice, coaching, or a gentle kick in the ass to get unstuck. (In fact, that is Perry listening to David Kelley while they were coaching teams -- David is the d schools main founder).

And I noticed when watching master innovation teacher and coach Perry Klebahn in action at the Stanford d. School that he hardly ever sits down for long, he is always on the prowl, walking over to members of his team to ask how things are going, to give a bit of advice, and to find out what needs to be fixed -- and is constantly walking over to to watch teams of students or executives who are working on creative tasks to see if they need a bit advice, coaching, or a gentle kick in the ass to get unstuck. (In fact, that is Perry listening to David Kelley while they were coaching teams -- David is the d schools main founder).

Of course, there are times when sitting down is best: During long meetings, when you want to unwind, when relaxed contemplation is in order. But these thoughts inspired a couple questions that many of us -- including me -- need to ask ourselves about the groups we work in and lead: Would it help if I stood up? Would it help if we all stood up?

This all reminded me of this passage from Good Boss, Bad Boss (from the chapter on how the best bosses "Serve as a Human Shield"):

In Praise of Stand-Up Meetings

I've been fascinated by stand-up meetings for years. It started when Jeff Pfeffer and I were writing Hard Facts, our book on evidence-based management. We often met in Jeff's lovely house, typically starting-out in his kitchen. But we usually ended-up in Jeff's spacious study -- where we both stood, or more often, Jeff sat on the lone chair, and I stood. Meetings in his study were productive but rarely lasted long. There was no place for me sit and the discomfort soon drove me out the door (or at least back to the kitchen). We wondered if there was research on stand-up meetings, and to our delight, we found an experiment comparing decisions made by 56 groups where people stood-up during meetings to 55 groups where people sat down. These were short meetings, in the 10 to 20 minute range, but the researchers found big differences. Groups that stood-up took 34% less time to make the assigned decision, and there were no significant differences in decision quality between stand-up and sit-down groups.

Stand-up meetings aren't just praised in cute academic studies. Robert Townsend advised in Up the Organization, "Some meetings should be mercifully brief. A good way to handle the latter is to hold the meeting with everyone standing-up. The meetees won't believe you at first. Then they get very uncomfortable and can hardly wait to get the meeting over with."

I keep finding good bosses who use stand-up meetings to speed things along. One is David Darragh, CEO of Reily, a New Orleans-based company that specializes in southern foods and drinks. They produce and market dozens of products such as Wick Fowler's 2-Alarm Chili, CDM Coffee and Chicory, No Pudge Fat Free Brownie Mix, and Luzianne Tea. David and I were having a rollicking conversation about how he works with his team. I started interrogating closely after he mentioned the 15 minute stand-up meeting held in his office four mornings a week. We since exchanged a series of emails about these meetings. As David explains:

"The importance of the stand-up meeting is that it can be accomplished efficiently and, therefore, with greater frequency. Like many areas of discipline, repetition begets improved results. The same is true with meetings. The rhythm that frequency generates allows relationships to develop, personal ticks to be understood, stressors to be identified, personal strengths and weaknesses to be put out in the light of day, etc. The role of stand-up meetings is not to work on strategic issues or even to resolve an immediate issue. The role is to bubble up the issues of the day and to identify the ones that need to be worked outside the meeting and agree on a steward to be responsible for it. With frequent, crisp stand up meetings, there can never be the excuse that the opportunity to communicate was not there. We insist that bad news travels just as fast as good news"

The team also has a 90 minute sit-down meeting each week, where they dig into more strategic issues. But the quick daily meetings keep the team connected, allow them to spot small problems before they become big ones, and facilitate quick and effective action.

Stand-up meetings aren't right for every meeting or boss. As we saw in the last chapter in the broken Timbuk2 all-hands meeting, part of the problem with that 45 or so minute gathering was there was no place for most people to sit, which fueled the group's grumpiness and impatience. The key lesson is that the best bosses constantly look for little ways to use everyone's time and energy more efficiently and respectfully. They keep unearthing traditions, procedures, or other things that needlessly slow people down. In many cases, these speed bumps have been around so long that people don't even realize they exist or that they do more harm than good. Try to look at what you and your people do through fresh eyes. Bring in someone who "doesn't know any better," and ask them: What can I do to help my people travel through the day with fewer hassles?

What do you think? How does standing-up help in what you do? When is it a bad idea?

P.S. Check out this Wall Street Journal article on stand-up meetings as part of the "Agile" software development process, particularly the "daily scrum."

Amazon Can Say "Asshole" But You Can't

This isn't the first time I have written a post like this, but the experience a No Asshole Rule fan had with Amazon today reminded me of how weird their policies are around the book's title. In short, if you write a review of the book, and you use the word "asshole, they not only reject it, they won't let you edit it or submit another review. Over the years, at least ten people who have written submitted positive reviews have written me to complain about this problem (I suspect people who have written negative reviews have the same problem, but they don't write me).

I got a new one today from Bill. There isn't much hope of changing the policy: I've tried and so has my publisher. Bill, we will try again but will probably fail. But I do appreciate all the effort you took to write such a nice and detailed review even if Amazon won't print it.

Also, to all readers, note Bill only used the word "Asshole" once, at the very end,when he mentioned the book's title. But that was enough for Amazon's automated screening to kill the review and freeze him out from repairing it or submitting another one!

Here it is, and thanks again Bill!

By Bill SM

Amazon Verified Purchase(What's this?)

This review is from: The No Asshole Rule: Building a Civilized Workplace and Surviving One That Isn't (Paperback)

Through eight years of higher education, and 20-odd years in the work-force, this book is the most important, eye-opening, business self-help book I have ever read; it literally changed my way of thinking about myself as a professional, and my functioning as an employee. I have recommended it to hundreds of college students and dozens of colleagues and friends. I have lent it to and bought it for people who needed protection from JERKS in their own places of work, and I have given it as a gift to people whom I could see had the potential to become JERK bosses - as an inoculation, if you will.

In all my years of gainful employment, I had never spent more than 3 years at any one job, picking up and leaving each time because of the JERKS (or so I thought) to whom I had to answer and with whom I had to contend. Repeatedly, I found myself saying, "I will not be associated with him/her," and then I picked up my family and moved to a new city and a new job, where I kept finding the same problems - JERKS were everywhere!

I listened to this book on CD (a good recording by actor Kerin McCue) and then read the print version after having separated from my last place of work in the industry in which I had intended to make my entire career. Filled with anger and bitterness at having been treated poorly, bullied, and abruptly canned after seven months of my new three-year contract in my new city, Professor Sutton's book finally helped me to recognize my own role in all of this - I had never learned how to deal with JERKS, and I didn't recognize how much power I was letting them have over me (and therefore my family, as well).

Since experiencing the revelations this book offered, I have launched a new career in a different, but related, industry, and I am once again climbing the corporate ladder in a company for which I have now been working for five years and going strong. I am much happier and more relaxed as a professional than ever before. I still have to contend with JERKS, but they do not bother me anymore. I have come to realize that their being horrible human beings has nothing to do with me, and they would be horrible to anyone else, as well, which is where I am now able to step in and offer support and perspective to others.

I only wish this book had been written and published two years earlier! If it had, I would still be earning twice the money I am now. Nevertheless, The No Asshole Rule helped me to understand myself and my career, and laid the groundwork for my current and future success.

March 29, 2012

A Method For Determining If A Boss Is Self-Aware (And Listens Well)

I was talking with a journalist from Men's Health today about how bosses can become more aware of how they act and are seen by the people they lead, and how so many bosses (like most human-beings) can be clueless of how they come across to others. This reminded of a method I used some years back with one boss that proved pretty effective for helping him come to grips with his overbearing and "all transmission, no reception" style; here is how it is described in Good Boss, Bad Boss:

A few years ago, I did a workshop with a management team that was suffering from "group dynamics problems." In particular, team members felt their boss, a senior vice-president, was overbearing, listened poorly, and routinely "ran over" others. The VP denied all this and called his people "thin-skinned wimps."

I asked the team – the boss and five direct reports -- to do a variation of an exercise I've used in the classroom for years. They spent about 20 minutes brainstorming ideas about products their business might bring to market; they then spent 10 minutes narrowing their choices to just three: The most feasible, wildest, and most likely to fail. But as the group brainstormed and made these decisions, I didn't pay attention to the content of their ideas. Instead, I worked with a couple others from the company to make rough counts of the number of comments made by each member, the number of times each interrupted other members, and the number of times each was interrupted. During this short exercise, the VP made about 65% of the comments, interrupted others at least 20 times, and was never interrupted once. I then had the VP leave the room after the exercise and asked his five underlings to estimate the results; their recollections were quite accurate, especially about their boss's stifling actions. When we brought the VP back in, he recalled making about 25% of the comments, interrupting others two or three times, and being interrupted three or four times. When we gave the boss the results, and told him that his direct reports made far more accurate estimates, he was flabbergasted and a bit pissed-off at everyone in the room.

As this VP discovered, being a boss is much like being a high status primate in any group: The creatures beneath you in the pecking order watch every move you make – and so they know a lot more about you than you know about them.

My colleague Huggy Rao has a related test he uses to determine if a boss is leading in ways that enables him or her to stay in tune with others. In addition to how much the boss talks, Huggy counts the proportion of statements the boss makes versus the number of questions asked. "Transmit only bosses" make lots of statements and assertions and ask few questions.

What do you think of these assessment methods? What other methods have you used to determine how self-aware and sensitive you are other bosses are -- and to makes things better?

March 22, 2012

Hollow Visions, Bullshit, Lies and Leadership Vs. Management

Fast Company has been reprinting excerpts from the new chapter in the Good Boss, Bad Boss paperback. The fifth and current piece 'Why "Big Picture Only" Bosses Are The Worst' deals with a theme I have raised both here and at HBR before: My argument is that, although the distinction between "management" and "leadership" is probably accurate, the implicit or explicit status differences attached to these terms are destructive.

One of the worst effects is that too many "leaders" fancy themselves as grand strategists and visionaries and who are above the "little people" that are charged with refining and implementing those big and bold ideas. These exalted captains of industry develop the grand vision for the product, the film, the merger, or whatever -- and leave the implementation to others. This was one of Carly Fiorina's fatal flaws at HP: she loved speeches and grand gestures like the Compaq merger, but didn't have much patience for doing what was required for making things work. By contrast, this is the strength of Pixar leaders like Ed Catmull, John Lasseter, and Brad Bird. Yes, they have grand visions about the story and market for every film, but they sweat every detail of every frame and worry constantly about linking their big ideas to every little detail of their films.

As Teresa Amabile and Steve Kramer show in their masterpiece The Progress Principle, the best creative work depends on getting the little things right. James March, perhaps the most prestigious living organizational theorist, frames all this in an interesting way, arguing that the effectiveness of organizations depends at least as much on the competent performance of ordinary bureaucrats and technicians who do their jobs well (or badly) day in and day out as on the bold moves and grand rhetoric of people at the top of the pecking order. To paraphrase March, organizations need both poets and plumbers, and the plumbing is always crucial to organizational performance. (See this long interview for a nice summary of March's views).

To be clear, I am not rejecting the value of leadership, grand visions, and superstars. But just as our country and the rest of the world is suffering from the huge gaps between the haves and have nots, too many organizations are doing damage by giving excessive credit, stature, and dollars to people with the big ideas and giving insufficient kudos, prestige, and pay to people who put their heads down and make sure that all the little things get done right.

Our exaggerated faith in heroes and the instant cures they so often promise has done a lot of damage to our society too -- not just to organizations. In this vein, I wrote a piece in BusinessWeek a few years back after re-reading The Peter Principle. I argued that the emphasis on dramatic and bold moves and superstars, and our loss of respect for the crucial role of ordinary competence, was likely an underlying cause of the 2008-2009 financial meltdown:

If Dr. Peter were alive today, he'd find that a new lust for superhuman accomplishments has helped create an almost unprecedented level of incompetence. The message has been this: Perform extraordinary feats, or consider yourself a loser.

We are now struggling to stay afloat in a river of snake oil created by this way of thinking. Many of us didn't want to see the lies, exaggerations, and arrogance that pumped up our portfolios. Instead we showered huge rewards on the false financial heroes who fed our delusions. This is the Bernie Madoff story, too. People may have suspected that something wasn't quite right about the huge returns on their investments with Madoff. But few wanted to look closely enough to see the Ponzi scheme.

I am not saying that we don't need heroes and visionaries. Rather, we need leaders who help us link big ideas to the little day to day accomplishments that turn dreams into realities. To paraphrase my friend Peter Sims, author of Little Bets, we need leaders who can weave together the "birds eye view," the big picture, with "the worm's eye view," the nuances and tiny little actions required to make bold ideas come to life.

March 20, 2012

Join Reid Hoffman and Ben Casnocha: A Webcast on The Start-Up of You

I just got this invitation. Reid is widely known as one of the smartest people in Silicon Valley and as one of "the good guys." I have also heard great reports about Reid and Ben's new book too, but haven't read it. Reid also recently gave a talk at Stanford you might check out. Here is the invite:

Reid Hoffman and Ben Casnocha — authors of the #1 New York Times bestseller The Start-Up of You — are hosting a live, hour-long webcast in which they will discuss how you can accelerate your career today.

You will learn the best practices of some of the most successful start-ups on the planet (like PayPal and LinkedIn), and how these strategies can be applied to your career -- no matter your industry or job function. You will learn how to launch career plans amid uncertainty; how to change jobs based on what you learn; how to generate breakout opportunities; how to take intelligent risks; how to develop real relationships and build an effective professional network. Most of all, you will learn how to *think* like an entrepreneur when steering the start-up that is your career.

When: Thursday, March 29, at 6:30 PM PST

Where: http://ustre.am/INJs

As a special perk for my readers, Reid and Ben will prioritize answering your questions, so post them in the comments below or tweet the question with the hashtag #startQ.

March 19, 2012

Creativity: Another Reason that Having a Drink -- or Two -- at Work Isn't All Bad

Last April, I had fun writing a guest column for Cnn.Com arguing that having an occasional drink with your colleagues while you are at work isn't all bad:

In addition to its objective physiological effects, anthropologists have long noted that its presence serves as a signal in many societies that a "time-out" has begun, that people are released, at least to a degree, from their usual responsibilities and roles. Its mere presence in our cups signals we have permission to be our "authentic selves" and we are allowed -- at least to a degree -- to reveal personal information about ourselves and gossip about others -- because, after all, the booze loosened our tongues. When used in moderate doses and with proper precautions, participating in a collective round of drinking or two has a professional upside that ought to be acknowledged.

Now there is a new study that adds to the symbolic (and I suppose objective) power of alcohol to bring about positive effects. The folks over at BPS Research Digest offer a lovely summary of an experiment called "Uncorking the Muse" that shows "mild intoxication aids creative problem solving." The researchers had male subjects between the ages of 21 and 30 consume enough vodka to get their blood alcohol concentration to .07, which is about equal to consuming two pints of beer for an average sized man. Then they gave them a standard creativity task 'the "Remote Associates Test", a popular test of insightful thinking in which three words are presented on each round (e.g. coin, quick, spoon) and the aim is to identify the one word that best fits these three (e.g. silver).'

The tipsy respondents performed better on the test than subjects in a sober control group:

1. "they solved 58 per cent of 15 items on average vs. 42 per cent average success achieved by controls"

2. "they tended to solve the items more quickly (11.54 seconds per item vs. 15.24 seconds)"

The reasons they did better and moved faster appear to be lack of inhibition ("intoxicated participants tended to rate their experience of problem solving as more insightful, like an Aha! moment, and less analytic") and, following past research, people with superior memories tend to do worse on this task -- because drinking dulls memory, it may help on the Remote Associates Test. The researchers also speculate that "being mildly drunk facilitates a divergent, diffuse mode of thought, which is useful for such tasks where the answer requires thinking on a tangent."

I am not arguing that people who do creative work ought to drink all day -- there are two many dangers. As I warned in the CNN piece, booze is best consumed in small doses and with proper precautions. And of course people who don't or should not drink for health, religious, or other reasons ought not to be pressured to join in the drinking.

Yet, this study, when combined when with other work suggesting that drinking can serve as a useful social lubricant, suggest that having a drink or two with your colleagues at the end of the day now and then, and kicking around a few crazy ideas, might both enhance social bonds and generate some great new ideas. The payoff might include innovative products, services, experiences and the like -- if you can remember those sparkling insights after you sober up!

P.S. The citation is Jarosz, A., Colflesh, G., and Wiley, J. (2012). Uncorking the muse: Alcohol intoxication facilitates creative problem solving. Consciousness and Cognition, 21 (1), 487-493

March 18, 2012

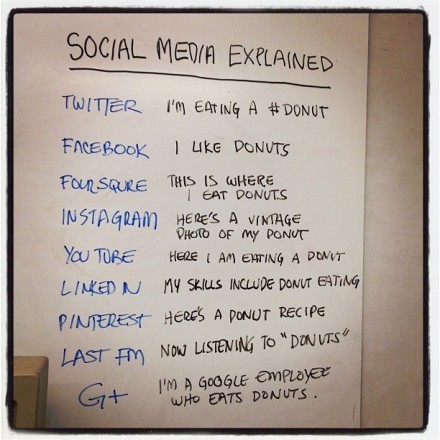

Social Media Explained With Donuts: From Geek.Com

March 17, 2012

Diego Rodriguez: This is What Leadership Should Look Like at IDEO

As long-time readers of this blog know, I am a big admirer (and long time friend) of Diego Rodriguez. Diego is a partner at IDEO and runs the flagship Palo Alto office, and he writes the always provocative blog Metacool. Diego's IDEO colleague, Tatyana Mamut, stopped by Stanford last week to serve as judge for the final project in our course on scaling-up excellence (they were wonderful, but that is another story).

Somehow, we got to talking about leadership and she told me about a video that Diego had shown people and told them "This is what leadership should look like at IDEO." Watch it here. You have to see it, I won't tell you anything else.

P.S. As a bonus, if you click on the link for Tatyana, you get a great short talk on how tools, rules, and norms and how they explain the spread of deodorant use in Russia. It reminds of when my dissertation adviser -- Bob Kahn, half jokingly -- defined organizations as "rules, tools, and fools."

March 16, 2012

The Hallmarks of Great Leaders -- and the Needs of Younger Workers --- are Timeless

Fast Company has another excerpt from the new chapter in Good Boss, Bad Boss out today -- one that goes against things that many so-called management gurus often say. My main point i those who argue management needs to be re-invented are misguided -- they massively overstate the case and have incentives for doing so, but it doesn't stand up to the evidence. Here is opening of the piece and you can read the rest here:

A lot of people write business books: about eleven thousand are published each year. There are armies of consultants, gurus, and wannabe thought leaders, and thousands of management magazines, radio and TV shows, websites, and blogs.

These purveyors of management knowledge have incentives for claiming their ideas are "new and improved" rather than the same old thing. One twist, which I've seen a lot lately, is the claim that management or leadership needs to be reinvented. Many reasons given for this need seem sensible: Gen X and Gen Y require different management techniques; outsourcing, globalization, and information technology means working with people we rarely if ever meet in person; the pressure to think and move ever faster is unprecedented; so many employees are disengaged that they need to be managed so they feel appreciated.

Yet, no matter how hard I look at studies by academics and consulting firms, or at contrasts between successful and unsuccessful leaders, I can't find persuasive evidence of substantial change in the kinds of bosses people want to become or work for, or that enable human groups and organizations to thrive. Changes such as the computer revolution, globalization, and distributed teams mean that if you are a boss, staying in tune with followers is more challenging than ever. And, certainly, bosses need to be more culturally aware because many workplaces are composed of more diverse people.

But every new generation of bosses faces hurdles that seem to make the job tougher than it ever was. The introduction of the telephone and air travel created many of the same challenges as the computer revolution--as did the introduction of the telegraph and trains. Just as every new generation of teenagers believes they have discovered sex and their parents can't possibly understand what it feels like to be them, believing that that no prior generation of bosses ever faced anything like this and these crazy times require entirely new ways of thinking and acting are likely soothing to modern managers. These beliefs also help so called experts like me sell our wares. Yet there is little evidence to support the claim that organizations—let alone the humans in them—have changed so drastically that we need to invent a whole new kind of boss.

I'd love your reactions!

P.S. Note that Gen Y and Gen X really aren't much different than any other new generation of employees in terms of what they want -- even though there is a small industry around dealing with these so-called new kinds of workers. Certainly, younger workers want different things than older workers -- but this has always been the case and what they want has always been pretty similar -- be they baby boomers, Gen X, Gen Y, or whatever. See this piece by Wharton's Peter Cappelli, perhaps the most prestigious talent researcher in academia, where he discusses the evidence, which show a few differences, but nothing dramatic.

March 14, 2012

Are Incompetent and Nice Bosses Even Worse The Competent Assholes? An Excerpt from My New Chapter

Tomorrow is the official publication day for the Good Boss, Bad Boss paperback. It contains a new chapter called "What Great Bosses Do," which digs into some of the lessons I learned about leadership since publishing the hardback in September 2010. I have already published excerpts from the new chapter on power poisoning, bad apples, and embracing the mess at Fast Company.

As I am teaching all day tomorrow, I am publishing another here today excerpt here to mark the occasion. It considers one of the most personally troubling lessons I've learned (or at least am on the verge of believing). I am starting to wonder, as the headline says, if nice but incompetent bosses are even worse (at least in some ways and at certain times) than competent assholes.

Now, to be clear, they both suck and having to choose between the two is sort of like deciding whether to be kicked in the stomach or kicked in the head. And I have even suggested here that there might be certain advantages to having a lousy boss (and readers came up with numerous other great reasons). But I have seen so much damage done by lousy bosses who are really nice people in recent years that I am starting to wonder...

Here is the excerpt from the new chapter (the 4th of 9 lessons):

4. Bosses who are civilized and caring, but incompetent, can be really horrible.

Perhaps because I am the author of The No Asshole Rule, I kept running into people—journalists, employees,project managers, even a few CEOs—who picked a fight with me. They would argue that good bosses are more than caring human beings; they make sure the job gets done. I responded by expressing agreement and pointing out this book defines a good boss as one who drives performance and treats people humanely. Yet, as I started digging into the experiences that drove my critics to raise this point— and thought about some lousy bosses—I realized I hadn't placed enough emphasis on the damage done, as one put it, by "a really incompetent, but really nice, boss."

As The No Asshole Rule shows, if you are a boss who is a certified jerk, you may be able to maintain your position so long as your charges keep performing at impressive levels. I warned, however, that your enemies are lying in wait, and once you slip up you are likely to be pushed aside with stunning speed. In contrast, one reason that baseball coach Leo Durocher's famous saying "Nice guys finish last" is sometimes right is that when a boss is adored by followers (and peers and superiors, too) they often can't bring themselves to bad-mouth, let alone fire or demote, that lovely person.

People may love that crummy boss so much they constantly excuse, or don't even notice, clear signs of incompetence. For example, there is one senior executive I know who is utterly lacking in the necessary skills or thirst for excellence his job requires. He communicates poorly (he rarely returns even important e-mails and devotes little attention to developing the network of partners his organization needs), lacks the courage to confront—let alone fire—destructive employees, and there are multiple signs his organization's reputation is slipping. But he is such a lovely person, so caring and so empathetic, that his superiors can't bring themselves to fire him.

There are two lessons here. The first is for bosses. If you are well-liked, civilized, and caring, your charms provide

protective armor when things go wrong. Your superiors are likely to give you the benefit of the doubt as well

as second and third chances—sometimes even if you are incompetent. I would add, however, that if you are a truly crummy boss—but care as much for others as they do for you—stepping aside is the noble thing to do. The second lesson is for those who oversee lovable losers. Doing the dirty work with such bosses is distasteful. But if rehabilitation has failed—or things are falling apart too fast to risk it—the time has come to hit the delete button.

Thoughts?

Robert I. Sutton's Blog

- Robert I. Sutton's profile

- 266 followers