Robert I. Sutton's Blog, page 5

September 24, 2012

Rare Wisdom from Citrix CEO Mark Templeton about Hiearchy and Respect

I confess that as an avid reader of The New York Times, I have been disappointed in recent years because they devote too much space to interviews with CEOs and other bosses. Notably, it seems to me that they run the same column twice every Sunday: Adam Bryant's "The Corner Office" and another interview column called "The Boss." I do love many of these interviews anyway, as The Times gets interesting people and their editing makes things better. And I am a big fan of Adam Bryant's book, The Corner Office, as it did a great job of transcending the column. What bugs me, however, is that The Times devotes so much of the paper to interviews now, I suspect, because it is simply cheaper than producing hard-hitting investigative journalism. They do an occasional amazing in-depth story, but there is too much fluff and not enough tough for my tastes.

That said, some of the interviews are still striking. One of the best I have ever read appeared yesterday, with Citrix CEO Mark Templeton. The whole interview is unusually thoughtful and reminds me that people who don't see themselves as CEOs and don't lust after the position often turn out to be the best candidate for the job (related point: see this study that shows groups tend to pick people with big mouths to lead but that less pushy and extroverted leaders tend to lead more effective teams -- at least when the teams were composed of proactive members). In particular, however, I was taken with this quote from Templeton:

You have to make sure you never confuse the

hierarchy that you need for managing complexity with the respect that

people deserve. Because that’s where a lot of organizations go off

track, confusing respect and hierarchy, and thinking that low on

hierarchy means low respect; high on the hierarchy means high respect.

So hierarchy is a necessary evil of managing complexity, but it in no

way has anything to do with respect that is owed an individual.

If you say that to everyone over and over and over, it allows people in

the company to send me an e-mail no matter what their title might be or

to come up to me at any time and point out something — a great idea or a

great problem or to seek advice or whatever.

There is so much wisdom here, including:

1. While there are researchers and other idealists running around and urging companies to rip down their hierarchies and to give everyone equal power and decision rights, and this notion that we are all equal in every way may sound like a lovely thought, the fact is that people prefer and need pecking orders and other trappings of constraint such as rules and procedures. As Templeton points out so wisely, organizations need hierarchies to deal with complexity. Yes, some hierarchies are better than others -- some are too flat, some have to many layers, some have bad communication flows, and organizational designers should err on making them as "light" and "simple" as possible -- but as he says, they are a necessary evil.

2. His second point really hits home and is something that all too many leaders -- infected with power poisoning -- seem to forget as they sit at the top of the local pecking order "thinking that low on

hierarchy means low respect; high on the hierarchy means high respect." When leaders believe and especially act on this belief, all sorts of good things happen, including your best people stay (even if you can't pay them as much as competitors), they feel obligated to return the respect by giving their all to the organization (and feel obligated to press their colleagues to do as well), and a norm of treating people with dignity and respect emerges and is sustained. Plus, as Templeton points out, because fear is low and respect is high, people at the top tend to get more truth -- and less CYA and ass-kissing behavior.

No organization is perfect. But a note for all the bosses out there. If you read Templeton's quote a few times and think about what it means for running your organization, it can help you take a big step toward excellence in terms of both the performance and well-being among the people you lead.

August 31, 2012

Too Big to Fail, Economies of Scale, Cities, and Companies

I've been reading research on organizational size and performance as it is pertinent to the book that Huggy Rao and I are writing on scaling-up excellence. In doing so, I also have been following the debate about banks and whether the assertion that both a cause of the meltdown and a risk for future fiascos is that banks are "too big to fail." Of course, the debate is hard to sift through because there is so much ideology and so many perverse incentives (example: the bigger the bank, the more the CEO, top team, and board will -- in general -- be compensated).

Although bankers have been generally silent on this, some have started speaking-up since former Citigroup CEO Sandy Weil -- the creator of that huge bank (which lives on courtesy of the U.S. taxpayers) -- joined the chorus and argued that big banks ought to be broken-up. Simon Johnson -- an MIT professor -- had an interesting editorial in the New York Times yesterday where he reviews some of the recent arguments by bankers and lobbying groups that very big banks are still a good idea -- and refutes their arguments (and points out that both Democrats and more recently Republicans are starting to challenge the wisdom of mega-banks).

I especially want to focus on the "economies of scale argument," that argument that there are more efficiencies and other advantages enjoyed by larger systems in comparison to smaller ones. This appears to be the crux of an editorial in defense of large banks published in the NYT on August 22nd by former banking executive William B. Harrison Jr. I was struck by one of Johnson's retorts:

As I made clear in a point-by-point rebuttal

of Mr. Harrison’s Op-Ed commentary, his defense of the big banks is not

based on any evidence. He primarily makes assertions about economies of

scale in banking, but no one can find such efficiency enhancements for

banks with more than $100 billion in total assets – and our largest

banks have balance sheets, properly measured, that approach $4 trillion.

Although I am interested in -- and an advocate -- of the power of growing bigger and better organizations at times, doing so is only justifiable in my view if excellence can at least be sustained and preferably enhanced, and the side-effects and risks to do not overwhelm the benefits. Unfortunately, the optimism among the bigger is better crowd often outruns the facts. For starters, I would love to see sound evidence that really really big organizations enjoy economies of scale and other performance advantages -- Wal-Mart might be such a case, they certainly have market power, the ability to bring down prices, and brand recognition -- but I can't find much systematic evidence for economies of scale across really big organizations. If Mr. Harrison is correct, for example, there isn't any evidence of increased efficiencies for banks over 100 billion in assets.

This debate reminds me of some fascinating research on the differences between cities and companies. Luis Bettencourt and Geoffery West of the Santa Fe Institute present fascinating evidence that larger cities are more efficient and effective than smaller ones. As they conclude in this article in Nature:

Three main characteristics vary systematically with population. One, the space required per capita shrinks, thanks to denser settlement and a more intense use of infrastructure. Two, the pace of all socioeconomic activity accelerates, leading to higher productivity. And three, economic and social activities diversify and become more interdependent, resulting in new forms of economic specialization and cultural expression. We have recently shown that these general trends can be expressed as simple mathematical ‘laws’. For example, doubling the population of any city requires only about an 85% increase in infrastructure, whether that be total road surface, length of electrical cables, water pipes or number of petrol stations.

OK, so it seems that economies of scale do exist for at least one kind of social system, cities. Does this provide hope for those bankers? Apparently not. Check out West's Ted Talk on "The Surprising Math Cities and Corporations." He concludes several interesting things about scaling. First, the bigger the biological system, the more efficient it becomes. Second, following the above quote and the logic that follows from organisms, cities become more efficient (and creative and financially successful too) as they become larger. Third, that cities rarely die, but organizations almost always do (he claims always). Fourth, he shows that companies do scale -- in fact he talks about Wal-Mart, shows their economies of scale, and describes his dataset of 23,000 companies. But the twist is that as companies become larger and older they become weighted down with bureaucracy and -- unlike cities -- the resulting internal friction both outweighs the benefits of economies of scale and renders them unable to to pull-off the radical innovations required to stay alive.

Here is this conclusion in more detail, from an article in The New York Times:

This raises the obvious question: Why are corporations so fleeting?

After buying data on more than 23,000 publicly traded companies,

Bettencourt and West discovered that corporate productivity, unlike

urban productivity, was entirely sublinear. As the number of employees

grows, the amount of profit per employee shrinks. West gets giddy when

he shows me the linear regression charts. “Look at this bloody plot,” he

says. “It’s ridiculous how well the points line up.” The graph reflects

the bleak reality of corporate growth, in which efficiencies of scale

are almost always outweighed by the burdens of bureaucracy. “When a

company starts out, it’s all about the new idea,” West says. “And then,

if the company gets lucky, the idea takes off. Everybody is happy and

rich. But then management starts worrying about the bottom line, and so

all these people are hired to keep track of the paper clips. This is the

beginning of the end.”

The danger, West says, is that the inevitable decline in profit per

employee makes large companies increasingly vulnerable to market

volatility. Since the company now has to support an expensive staff —

overhead costs increase with size — even a minor disturbance can lead to

significant losses. As West puts it, “Companies are killed by their

need to keep on getting bigger.”

There are still advantages to size despite these rather discouraging data" market power, legitimacy, the ability to do complex things that require multiple disciplines, and brand recognition come to mind. And there are studies by economists that show economies of scale under some conditions. Some organizations are also better than others at limiting the burdens of bureaucracy as they grow-- Wal-Mart is one of them. As a practical matter, when I think of Bettencourt and West's data and combine it with Ben Horowitz's amazing post on scaling, it appears his advice to "give ground grudgingly," to add as little structure and process as you can get away with given your organization's size and complexity, is even more sound than I originally thought.

As with many researchers, West has a healthy ego and states his findings with more certainty than is probably warranted. But these are -- unlike the bankers -- evidence-based statements, and when I combine them with what Huggy and I are learning about how hard scaling is to do well (there are big differences between companies that do it well versus badly), the lack of evidence for economies of scale in really big banks, and a system where the primary defenders of really big banks have strong incentives and weak evidence to support their positions, I am hoping that in a political season where my country seems hopelessly split on so many issues, perhaps this is one where both sides can come together and hold an evidence-based position.

August 27, 2012

Malicious Compliance

I appreciate the interesting comments and suggestions in response to my last post on different levels of felt accountability. Readers may recall that I proposed -- from best to worst - that a team or organization can be characterized as having people who feel everything from authorship. mutual obligation, indifference, and mutual contempt. I have especially been thinking about this comment from Justdriven, which builds on a prior comments by AnnieL:

"Regarding

your first question, I think AnneL may have identified a fifth category

between mutual obligation and indifference which would be fear driven

box checking. This would be the case where individuals follow procedures

out of a fear of retribution rather than an endorsement of said

procedures. This would seem to be what the pilot experienced. This stage

would be a slippery slope that takes you from mutual obligation to

indifference and then contempt."

I am taken with "fear driven box-checking" as it seems to be both a symptom and a cause, where people who feel powerless have no ability -- and thus no obligation -- to help make things go well because the system makes it impossible regardless of how good their intentions might be. This comment also got me thinking about how, in some systems, people can zoom past indifference and move to mutual contempt by following the rules exactly as a way to fight back against a bad system or boss -- especially when there are bad standing rules or orders for a given challenge. "Working to rule" is a classic labor slow down tactic, and there is some sweet revenge and irony when you get back at company or person that you don't like by following their instructions to the letter.

More broadly, I have been interested in the notion of "malicious compliance" for a long time. In Chapter 6 of Good Boss, Bad Boss I wrote about how it is sometimes used to get back at a bad or incompetent boss, or in the example below, by bosses to shield their people from a lousy boss up the chain of command:

I know bosses who employ the opposite strategy to undermine and drive out incompetent superiors. One called it “malicious compliance,” following idiotic orders from on high exactly to the letter, thereby assuring the work would suck. This is a risky strategy, of course, but I once had a detailed conversation with a manager at an electronics firm whose team built an ugly and cumbersome product prototype. After it was savaged by the CEO, the manager carefully explained (and documented) that his team had done exactly as the VP of Engineering ordered, and although he voiced early and adamant objections to the VP, he gave up because “it was like talking to a brick wall.”

So this manager and his team decided ‘Let’s give him exactly what he wants, so we just said “yes sir” and followed his lousy orders precisely.’ The VP of engineering lost his job as a result. Again, this is a dangerous and destructive strategy, and I would advise any boss to only use it as a last resort.

I would be curious to hear of other examples of malicious compliance -- and if you have any ideas of how to create conditions so it won't happen. Its is one of this sick but fascinating elements of organizational life.

August 23, 2012

On the Marginal Utility of Pure Economists

One of our most charming and well-read doctoral students (he is just finishing-up, in fact, I believe he is already a Ph.D), Issac Waisberg, just sent an old quote that is pretty funny. I apologize to my economist friends, but recent global events make this comment seem more true than ever:

In an essay about Walter Bagehot:

"I have been careful not to say that

the pure economist is valueless but, if I may borrow one of his own

conceptions, his marginal utility is low." F. S. Florence, The Economist,

July 25, 1953, 252.

If you check-out the link, you will see Bagehot was the editor of The Economist a long stretch in the 19th century" "For 17 years Bagehot wrote the main article, improved and expanded the

statistical and financial sections, and transformed the journal into one

of the world’s foremost business and political publications. More than

that, he humanized its political approach by emphasising social

problems." It sounds like he was great editor, but I still love the snarky and well-crafted dig.

August 22, 2012

Felt Accountability: Some Emerging Thoughts

This blog and much of the rest of my life were swamped last week by the intense reactions to the story about how badly United Airlines treated Phoebe and her parents when she traveled as an unaccompanied minor. You can read the blog post with the original story (and the 90 comments that were not too hostile to print) and the family's statement if you missed it. Also, Diego at Metacool did an insightful post about why the story went so viral.

At some point, I should write a post with the twists and turns of the story: the surprising hostility, the lies and veiled threats from the media, the stories about United that are far worse than the one published here (warning: stranded older teenagers might be worse than stranded young kids in some ways as they fall into a weird no-mans-land), and the senior executive ( I won't name him, he can out himself) who is on United constantly because he has no choice for his job, despises what they have devolved to, and reports he is sending back the expensive gift he got a few days ago to thank him for the 2 million miles he has flown with United -- he is going to suggest that they use the money to give some passenger a little better (or at least less bad) service.

As I recover from all this madness, I continue to think about felt accountability, the concept that I used to frame the United story. Huggy Rao and I are rather obsessed with this notion as it is so central to scaling-up excellence -- and for de-scaling bad behavior of all kinds. United is, I believe, a place that has lost that feeling of mutual obligation to do the right thing, where management helps employees, employees help management, employees help each other, employees help customers, and where customers feel compelled to pitch and play a helpful role too.

I am thinking -- Huggy gets part of the blame here too -- that there might be four different levels or kinds of accountability that a group or organization might have, which go something like this:

Authorship

This comes from my friend, early stage venture capitalist, and d.school teaching star Michael Dearing -- we heard it just yesterday from him. This is what you get get in a small start-up, from an inventor, and yes, from book authors like me. That feeling that not only am I obligated to do the right thing, but that I am the person responsible for designing and making it as great as I can. Steve Jobs had this in spades, of course, but you mostly see it in smaller organizations or pockets of bigger organizations. I think of Brad Bird at Pixar as another example, especially his amazing efforts on The Incredibles, how it was his vision, but how he still instilled the feeling in so much of team: Whatever little part they were working on, he made many members of the team feel as if they were authors -- if you want the feel of working with Brad, although DVD's are fading, check out the "behind the scenes" material on The Incredibles DVD. Amazing stuff.

Mutual Obligation

David Novak, CEO of Yum! brands, argues that this should be the goal of a great leader, to create a place where it feels like you own it and it owns you. This is what United has lost, what I still feel at Virgin America, JetBlue, and Southwest most of the time. IDEO and McKinsey have the same feel, as do Procter & Gamble and GE. I saw it at the Cleveland Clinic when I was patient there. I also think of people who work for the Singapore government, who can be remarkable in this regard. These organizations aren't perfect, none can be, but there is palpable weight on people, they feel pressure to do the right thing even when no one is looking, as the old saying goes. And they pressure others to do so as well.

Indifference

Think of the average hair salon, where each stylist rents a chair. Or a group dental practice, where dentists share a common receptionist and a few services and little else. Some organizations are designed this way and can be quite effective. The mutual dependence is weak, it is a "we don't do much for you, so you don't have to do much for us" situation. People don't have contempt for their colleagues or customers, it is just indifference. I was thinking that United had devolved to this state. But after the deluge last week, I realized it was worse than that. Hence, my proposed last category.

Mutual Contempt

I first heard hints of this notion at an unnamed university I worked at briefly quite a few years ago. Right after I arrived, one of my new colleagues said something "this is the kind of place where, when you a full professor, you not only don't care about your colleagues, you feel good when something bad happens to them." I should hasten to add that this was probably an overstatement, that such contempt seemed to be largely between groups and departments, not so much within them -- and they have new leadership and things seem to be better.

BUT I also fear that this describes the modern United Airlines, everyone seems to despise everyone else. I hope I am wrong about this, but the awful stories rolled in from so many sources that it seems as if all the years of cost-cutting, all the battles with unions, all the management changes, all the stress that customers have endured over the years have conspired to bring the organization -- at least most it -- to this dark place. It appears that many United employees are keenly aware of this sad state of affairs and it hurts them deeply -- especially front line employees.

I was especially struck by a long comment from a guy who said he was a 25 year United pilot. If you want to read the whole thing, it takes awhile to get there from the original post as there are 90 comments, and you have to click about four pages back, it is by Greenpolymer, August 14th, at 9:24 pm. I think this link gets you to the right page if you scroll down toward the bottom.

This pilot tells a brief story earlier in the post that really got to

me. It reflects terribly on United's management, and shows that people who act on feelings they are accountable to passengers are punished -- despite claims by senior executives to the contrary:

I had the

gall to apologize to my 150 passengers for a shares delay of 45 minutes

one day. I was asked to write a letter of apology TO MANAGEMENT for

mentioning the problem. (I think the videos also say something about

being truthful and taking responsibility)

This is the worst -- and most disturbing -- part:

I used

to be the Captain who ran downstairs to make sure the jetway air

conditioning was cold and properly hooked up. Who helped the mechanic

with the cowling and held the flashlight for him. I used to write notes

to MY guests, and thank them for their business. I wrote reports,

hundreds of reports, on everything from bad coffee to more efficient

taxi techniques.

No more. I have been told to do my job, and I do my job. My love

for aviation has been ground into dust. After 15 years of being lied

to, deceived, ignored, blamed falsely; and watching the same mistakes

being made over and over again by a "professional management" that never

seems to learn from the copious reports of our new "watchers", I give.

It's not an easy thing to do. I am an Eagle Scout, an entrepreneur,

and a retired Air Force Officer with over 22 years of service. Those

twelve points of the Scout law still mean something to me, especially

the first three. I have been in great units and not so great units, and

the difference ALWAYS came down to LEADERSHIP. Most (and I will be the

first to admit not all) of the employees that you all have been talking

about here are desperate. They would give anything to find a LEADER,

with a VISION, and a sense of HONOR to lead this company.

Painful, isn't it? "I used to be... I used to be... I used to be." I think he is a victim of the years of contempt, which is something far more vile than indifference -- not just for United customers, but for people like him who want to care.

Once again, this post is just to explore some emerging ideas -- and to start stepping back from the United incident (although clearly I have not been completely successful at that). To return to the big picture:

1. Any comments on the my four categories? Do they ring true? Any advice?

2. Now the hard part. We will return to this one. How do you build an organization that starts and remains a place where felt accountability prevails? Tougher still, once it is lost -- as seems to be the case at United -- how do you get it back? Or is it impossible?

August 16, 2012

A Call for Change at United: A Statement from Annie and Perry Klebahn

My last post was about how United Airlines lost Phoebe, my friend’s 10-year old daughter. All of us involved in this story – especially parents Annie and Perry, NBC’s Diane Dwyer (the only media person that interviewed Annie and Phoebe), and me – were stunned to see how viral it went. A Google search last night revealed it was reported in at least 160 outlets – including England, France, and Germany with the facts based only on the post written here, Annie and Perry’s complaint letter, and United’s tepid apology. This blog received over 200,000 hits in the last two days; 2000 is typical. Annie and Perry have resisted the intrusive onslaught of media people (most were polite, several incredibly rude) and elected to do a single interview with Diane Dwyer. It appeared locally in the San Francisco Bay Area as well is in a shorter (but I think still excellent) form this morning on The Today Show. Here is the link to The Today Show video and to Diane’s written story on the local NBC site.

I also want to reprint United's statement because it lacks even a hint of empathy or compassion. Note that it does not question any of the facts put forth by Annie and Perry and also note that no attempt was made to reach out to Annie and Perry until United was contacted by NBC reporter Diane Dwyer. As one executive I know explained -- he is in what they call Global Services, the top 1% of United customers -- even the statement is a symptom of how deep the denial is and how shallow the humanity is in the company:

“We reached out directly to the Klebahns to apologize and we are reviewing this matter. What the Klebahns describe is not the service we aim to deliver to our customers. We are redepositing the miles used to purchase the ticket back into Mr. Klebahn’s account in addition to refunding the unaccompanied minor charge. We certainly appreciate their business and would like the opportunity to provide them a better travel experience in the future.“

Charles Hobart/United Airlines Spokesman

Annie and Perry have written a statement below and as you can see, they aren’t going to be doing any additional media and their focus is on persuading United to change its policies and procedures for handling unaccompanied minors. They ask the media and anyone else out there to please respect their privacy from now onward.

As they request, I will also shift my efforts here and elsewhere to trying to understand how United reached the point where they are so broken, developing ideas about what can be done to save them from themselves, and to press United to break out of its current denial and start down the road to redemption.

Here is the statement from Annie and Perry, again, please respect their privacy.

On behalf of the Klebahn family we appreciate your interest in our story. We feel strongly that United's program for handling unaccompanied minors is deeply flawed and that they need to seriously overhaul this program and their entire approach to customer service.

Hundreds of thousands of families send their kids on United each year as unaccompanied minors. We sent our daughter away to summer camp, but many families are separated for a variety of reasons and sending their kids on planes alone is part of their required routine. United offers this service, and families like us trust and rely on them to provide safe, secure passage for children. The age of the children United takes into their care is 5-11 years old and not all of them carry cell phones, nor have the maturity to know what to do in an emergency. It's astounding how many flaws there are in United's program but at a bare minimum we think they need to change the following:

United does not disclose that their unaccompanied minor service is outsourced to a third party vendor--this needs to change so parents can make an informed choice about who they are entrusting their children to when they travel alone

If United is going to continue offering this service to families they need to offer a dedicated 24/7 phone line that is staffed with a live human being in the U.S. so that parents have an active and real resource to use during their travel experience

United should also be required to alert parents immediately of travel delays and alternative plans for the minors in their care

It is still startling to us that after our unbelievable experience it took six weeks, and a press story by NBC, to have United even consider responding to our concerns and complaints. Our only goal in all of this is to have United acknowledge that their program is flawed, and to consider an immediate overhaul before another child gets lost or hurt. Getting our $99 back with a veiled apology means nothing given what we've been through.

As an organization United is broken. They have the worst customer rating of all airlines, they have the highest number of official complaints on the US Department of Transportation's website, and the largest number of negative comments on the Internet, Facebook and Twitter. How can they not notice that they are doing it wrong?

At this point the important thing for us is that our daughter is safe. We can only hope that making our story public will in some way make an impact by adding another voice to the many out there asking United to change. If you would like to add your voice too, please join our petition to change United's Unaccompanied Minor Program by signing your name to the petition we started on Change.org.

We would like to thank Diane Dwyer at NBC and Dr. Robert Sutton for their help telling this story. There will be no further comments or interviews.

Annie and Perry Klebahn

August 13, 2012

United Airlines Lost My Friend's 10 Year Old Daughter And Didn't Care

My colleague Huggy Rao and I have been reading and writing about something called "felt accountability" in our scaling book. We are arguing that a key difference between good and bad organizations is that, in the good ones, most everyone feels obligated and presses everyone else to do what is in their customer's and organization's best interests. I feel it as a customer at my local Trader Joe's, on JetBlue and Virgin America, and In-N-Out Burger, to give a few diverse examples.

Unfortunately, one place I have not felt it for years -- and where it is has become even worse lately -- is United Airlines. I will forgo some recent incidents my family has been subjected to that reflect the depth at which indifference, powerlessness, and incompetence pervades the system. An experience that two of my friends -- Annie and Perry Klebahn -- had in late June and early July with their 10 year-old daughter Phoebe sums it all-up. I will just hit on some highlights here, but for full effect, please read the entire letter here to the CEO of United, as it has all the details.

Here is the headline: United was flying Phoebe as an unaccompanied minor on June 30th, from San Francisco to Chicago, with a transfer to Grand Rapids. No one showed-up in Chicago to help her transfer, so although her plane made it, she missed the connection. Most crucially, United employees consistently refused to take action to help assist or comfort Phoebe or to help her parents locate her despite their cries for help to numerous United employees.

A few key details.

1. After Phoebe landed in Chicago and no one from (the outsourced firm) that was supposed to take her to her next flight showed up. Numerous United employees declined to help her, even though she asked them over and over. I quote from the complaint letter:

The attendants where busy and could not help her she told us. She told them she had a flight to catch to camp and they told her to wait. She asked three times to use a phone to call us and they told her to wait. When she missed the flight she asked if someone had called camp to make sure they knew and they told her “yes—we will take care of it”. No one did. She was sad and scared and no one helped.

2. Annie and Perry only discovered that something was wrong a few hours later when the camp called to say that Phoebe was not on the expected plane in Grand Rapids. At the point, both Annie and Perry got on the phone. Annie got someone in India who wouldn't help beyond telling her:

'When I asked how she could have missed it given everything was 100% on time she said, “it does not matter” she is still in Chicago and “I am sure she is fine”. '

Annie was then put on hold for 40 minutes when she asked to speak to the supervisor.

3. Meanwhile, Perry was also calling. He is a "Premier" member in the United caste system so he got to speak to a person in the U.S. who worked in Chicago at the airport:

"When he asked why she could not say but put him on hold. When she came back she told him that in fact the unaccompanied minor service in Chicago simply “forgot to show up” to transfer her to the next flight. He was dumbfounded as neither of us had been told in writing or in person that United outsourced the unaccompanied minor services to a third party vendor."

4. Now comes the most disturbing part, the part that reveals how sick the system is. This United employee knew how upset the parents were and how badly United had screwed-up. Perry asked if the employee could go see if Phoebe was OK:

"When she came back she said should was going off her shift and could not help. My husband then asked her if she was a mother herself and she said “yes”—he then asked her if she was missing her child for 45 minutes what would she do? She kindly told him she understood and would do her best to help. 15 minutes later she found Phoebe in Chicago and found someone to let us talk to her and be sure she was okay."

This is the key moment in the story, note that in her role as a United employee, this woman would not help Perry and Annie. It was only when Perry asked her if she was a mother and how she would feel that she was able to shed her deeply ingrained United indifference -- the lack of felt accountability that pervades the system. Yes, there are design problems, there are operations problems, but the to me the core lesson is this is a system packed with people who don't feel responsible for doing the right thing. We can argue over who is to blame and how much -- management is at the top of the list in my book, but I won't let any of individual employees off the hook.

5. There are other bad parts to the story you can see in the letter. Of course, they lost Phoebe's luggage and in that part you can see all sorts of evidence of incompetence and misleading statements, again lack of accountability.

6. When Anne and Perry tried to file a complaint, note the system is so bad that they wouldn't let them write it themselves and the United employee refused their request to have it read back to be fact-checked, plus there are other twists worth repeating:

We asked to have them read it back to us to verify the facts, we also asked to read it ourselves and both requests were denied. We asked for them to focus on the fact that they “forgot” a 10-year old in the airport and never called camp or us to let us know. We also asked that they focus on the fact that we were not informed in any way that United uses a third party service for this. They said they would “do their best” to file the complaint per our situation. We asked if we would be credited the $99 unaccompanied minor fee (given she was clearly not accompanied). They said they weren’t sure.

We asked if the bags being lost for three days and camp having to make 5 trips to the airport vs. one was something we would be compensated for (given we pay camp $25 every time they go to the airport). They said that we would have to follow up with that separately with United baggage as a separate complaint. They also said that process was the same—United files what they hear from you but you do not get to file the complaint yourselves.

7. The story isn't over and the way it is currently unfolding makes United looks worse still in my eyes. United had continued to be completely unresponsive, so Annie and Perry got their story to a local NBC TV reporter, a smart one who does investigations named Diane Dwyer. Diane started making calls to United as she may do a story. Well, United doesn't care about Phoebe, they don't care about Annie and Perry, but they do care about getting an ugly story on TV. So some United executive called Annie and Perry at home yesterday to try to cool them out.

That story was what finally drove me to write this because, well, if bad PR is what it takes to get them to pretend to care, then it is a further reflection of how horrible they have become. I figured that regardless of whether Diane does the story or not, I wanted to make sure they got at least a little bad PR.

I know the airline industry is tough, I know there are employees at United who work their hearts out every day despite the horrible system they are in, and I also know how tough cultural change is when something is this broken. But perhaps United senior executives ought to at least take a look at what happens at JetBlue, Virgin America, and Southwest. They make mistakes too, it happens, but when they do, I nearly always feel empathy for my situation and that the people are trying to make the situation right.

August 7, 2012

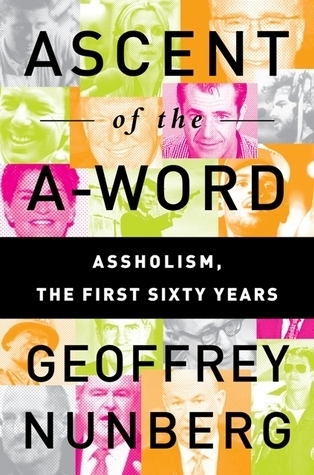

"Ascent of the A-Word" Geoffrey Nunberg's Great New Book

You have probably have heard of Geoffrey Nunberg -- that brilliant and funny linguist on NPR. He has a brand new asshole book called Ascent of the A-Word: Assholism, the First 60 years. I first heard about it a few weeks back when I was contacted by George Dobbins from the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco. He asked if I might moderate Nunberg's talk on August 15th, given we are now fellow asshole guys. I was honored to accept the invitation and I hope you can join us that evening -- you are in for a treat.

The book is a satisfying blend of great scholarship, wit, and splendid logic. It is a joy from start to finish, and the reviewers agree. I loved the first sentence of the Booklist review “Only an asshole would say this book is offensive. Sure, it uses the A-word a lot, but this is no cheap attempt to get laughs written by a B-list stand-up comic."

Nunberg starts with a magnificent first chapter called The Word, which talks about the battles between "Assholes and Anti-assholes." I love this sentence about the current state of public discourse in America "It sometimes seems as if every corner of our public discourse is riddled with people depicting one another as assholes and treating them accordingly, whether or not they actually use the word." As he states later in the chapter, he doesn't have a stance for or against the word (although the very existence of the book strikes me as support for it), the aim of the book is to "explore the role that the notion of the asshole has come to play in our lives."

He then follows-up with one delightful chapter after another, I especially loved "The Rise of Talking Dirty," "The Asshole in the Mirror," and "The Allure of Assholes." I get piles of books every year about bullies, jerks, toxic workplaces, and on and on. Although this isn't a workplace book, it is the best book I have ever read that is vaguely related to the topic.

I admired how deftly he treated "The Politics of Incivility" in the chapter on "The Assholism of Public Life." Nunberg makes a compelling argument that critics on the right and the left both use the tactic of claiming that an opponent is rude, nasty, or indecent -- that they are acting like assholes and ought to apologize immediately. Nunberg documents "the surge of patently phony indignation for all sides," be it calling out people for "conservative incivility" or "liberal hate." He captures much of this weird and destructive game with the little joke "Mind your manners, asshole."

I am barely scratching the surface, there is so much wisdom here, and it is all so fun. Read the book. Read and listen to this little piece that Nunberg did recently on NPR. This part is lovely:

Well, profanity makes hypocrites of us all. But without hypocrisy, how could profanity even exist? To learn what it means to swear, a child has to both hear the words said and be told that it's wrong to say them, ideally by the same people. After all, the basic point of swearing is to demonstrate that your emotions have gotten the better of you and trumped your inhibitions

We hope to see you at the Commonwealth Club in San Francisco on August 15th, it should be good fun.

August 1, 2012

Adding Women Makes Your Group Smarter -- The Evidence Keeps Growing

I was intrigued to see the new study that shows companies perform better when they have women on their boards. Check out this story and video at CNBC. Here is the upshot: "Credit Suisse analyzed more than 2,500 companies and found that companies with more than one woman on the board have outperformed those with no women on the board by 26 percent since 2005."

This result becomes even more compelling when you pair it with a rigorous study done a couple years ago. It showed that groups that have a higher percentage of women have higher "collective intelligence" -- they perform better across an array of difficult tasks "that ranged from visual puzzles to negotiations, brainstorming, games and complex rule-based design assignments," as this summary from Science News reports. In that research, the explanation was pretty interesting, as the authors set out to study collective intelligence, not gender. As Science News reported:

Only when analyzing the data did the co-authors suspect that the number of women in a group had significant predictive power. "We didn't design this study to focus on the gender effect," Malone says. "That was a surprise to us." However, further analysis revealed that the effect seemed to be explained by the higher social sensitivity exhibited by females, on average. "So having group members with higher social sensitivity is better regardless of whether they are male or female,"

Yet, despite all this, there is still massive sexism out there, especially in the upper reaches of many corporations. Note this report from the Women's Forum: "While women comprise 51% of the population, they make up only 15.7% of Fortune 500 boards of directors, less than 10% of California tech company boards, and 9.1% of Silicon Valley boards."

Pathetic huh? And it is pretty good evidence that all those sexist boys who love going to board meetings and retreats unfettered by those pesky women are just hurting themselves -- and their shareholders -- in the end. But perhaps there is justice in the world, as this just may be a case where "times wounds all heels."

Indeed, I wonder when we will see the first shareholders' suit where a company that has no women on the board, and suffers financial setbacks, is sued. Their failure to do so could be construed as a violation of their fiduciary responsibility. I know this sounds silly, it does to me. But lawyers and shareholders have sued -- and won -- over far more absurd things, as this would at least be an evidence-based claim (albeit one that stretches the evidence a bit too far for my tastes).

July 30, 2012

It is 1-3-2: Bronze Medal Winners are Happier than Silver

Yesterday I was sort of watching the Olympics -- reading the New York Times on my iPhone and occasionally glancing-up at the TV. There was some swimming race I wasn't following on the screen, but I looked-up because of all the enthusiasm by the guy on the screen. I was sure he had won a gold medal. Actually he hadn't, he had won bronze. His name is Brendan Hansen and he won it in the 100 meter breaststroke -- that is him above. In looking into his story, there are lots of reasons for him to be excited,as he was the oldest athlete in the field at 31, he had retired after the Beijing Olympics and done a comeback, he is only the 13th swimmer to win a medal after the age of 30, and he was not favored to win a medal. So he certainly deserves to be happy for many reasons.

But his joy on the screen reminded me of a cool study I first heard of nearly 20 years ago that, I strongly suspect, still holds true. A team of researchers found that, while gold medalists are happiest about their accomplishments, bronze medalists in the same events are consistently happier than sliver medalists. This was first established in a 1995 study by Vicki Medvec, Scott Madey, and Tom GIlovich. They coded videotapes of Olympic athletes from the Barcelona Spain summer games just after they learned of their performance, such as swimmers like Brendan Hansen right after their race. Then they coded the emotions again when they were awarded the medals on the podium.

They found that gold medalists displayed the strongest positive emotions, but bronze winners displayed stronger positive emotions than silver winners. The researchers replicated these same 1-3-2 findings in two other events, including the Empire State Games, an amateur competition in New York.

The researchers proposed that this finding is driven by what is called "counterfactual thinking," those thoughts of what might have been if something different had happened. In particular, they proposed that silver medals did upward comparisons to the gold medal winner, while the bronze medalists did downward comparisons to people who didn't win medals. As one of the authors, Tom GIlovich, explained to the Washington Post, "If you win a silver, it is very difficult to not think, 'Boy, if I had just gone a little faster at the end . The bronze-medal winners -- some of them might think, 'I could have gotten gold if I had gone faster,' but it is easier to think, 'Boy, I might not have gotten a medal at all!' "

I guess, to put perhaps too fine a point on it, silver medalists see themselves as the first loser, while bronze medalists see themselves as the last winner.

Like all research, this won't hold in every case, other factors come into play, especially -- as you could see with Brendan Hansen -- that happiness is also a function of what you get versus what you expect, and exceeding expectations is a universal trigger of positive emotion. So, for example, if the U.S. basketball team, who are strong "overdogs" get a gold get a bronze instead, I bet they won't act as happy as Hansen after they learn of the result.

Enjoy, and as we watch the Olympics, let's see if those bronze medalists look a bit happier than the silver medalists standing along aside them, as Medvec and her colleagues found.

P.S. Here is the source:

"When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic medalists." Medvec, Victoria Husted; Madey, Scott F.; Gilovich, Thomas. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 69(4), Oct 1995, 603-610.

Robert I. Sutton's Blog

- Robert I. Sutton's profile

- 266 followers