Robert I. Sutton's Blog, page 6

July 28, 2012

Wired Story Wraps With My Argument That Steve Jobs Is Like A Rorschach Test

I can't even recall quite when it happened, but several month back a Wired reporter named Ben Austen called me about a piece he was doing on Steve Jobs' legacy. I confess that kept the conversation short, in large part because I was just getting tired of the story -- and I think everyone else is as well. But this turned into the cover story, which -- despite my lack of enthusiasm about the topic -- is one of the most balanced and well-researched pieces I have seen. At least that became my biased opinion after I saw that he plugged my last two books in the final three paragraphs! Here is the whole piece if you want to read it and here is my argument -- you can read the whole excerpt about Jobs as a Rorschach test here, where I put it in earlier post. Here is how Ben Austen ended his piece:

As he was writing his 2007 book, The No Asshole Rule, Robert Sutton, a professor of management and engineering at Stanford, felt obligated to include a chapter on “the virtues of assholes,” as he puts it, in large part because of Jobs and his reputation even then as a highly effective bully. Sutton granted in this section that intimidation can be used strategically to gain power. But in most situations, the asshole simply does not get the best results. Psychological studies show that abusive bosses reduce productivity, stifle creativity, and cause high rates of absenteeism, company theft, and turnover—25 percent of bullied employees and 20 percent of those who witness the bullying will eventually quit because of it, according to one study.

When I asked Sutton about the divided response to Jobs’ character, he sent me an excerpt from the epilogue to the new paperback edition of his Good Boss, Bad Boss, written two months after Jobs’ death. In it he describes teaching an innovation seminar to a group of Chinese CEOs who seemed infatuated with Jobs. They began debating in high-volume Mandarin whether copying Jobs’ bad behavior would improve their ability to lead. After a half-hour break, Sutton returned to the classroom to find the CEOs still hollering at one another, many of them emphatic that Jobs succeeded because of—not in spite of—his cruel treatment of those around him.

Sutton now thinks that Jobs was too contradictory and contentious a man, too singular a figure, to offer many usable lessons. As the tale of those Chinese CEOs demonstrates, Jobs has become a Rorschach test, a screen onto which entrepreneurs and executives can project a justification of their own lives: choices they would have made anyway, difficult traits they already possess. “Everyone has their own private Steve Jobs,” Sutton says. “It usually tells you a lot about them—and little about Jobs.”

The point at which I really decided that the Jobs obsession was both silly and dangerous came about a month after his death. Huggy Rao and I were doing an interview on scaling-up excellence with a local CEO who founded a very successful company -- you would recognize the name of his company. After I stopped recording the interview, this guy -- who has a reputation as a caring, calm, and wickedly smart CEO -- asked Huggy Rao and me if we thought he had to be an asshole like Jobs in order for his company to achieve the next level of success.... he seemed genuinely worried that his inability to be nasty to people was career limiting.

Ugh. I felt rather ill and argued that it was important to be tough and do the dirty work when necessary, but treating people like dirt along way was not the path to success as a leader or a human-being. Perhaps this is my answer to the Steve Jobs Rorschach test: I believe that Jobs succeeded largely despite rather than because of the abuse he sometimes heaped on people. Of course, this probably tells you more about me than Jobs!

July 18, 2012

Charter Schools, California and New York City: $6000 vs. $13,500 Per Pupil

Huggy Rao and I have been reading and talking about charter schools for our scaling-up excellence project. Charter schools come in many forms, but the basic idea is that these often smaller and more focused schools are freed from many of the usual rules and constraints that other public schools face, and in exchange, are held more accountable for student achievement – on measures like standardized test scores, graduation rates, and the percentage of students who go onto college.

There is much controversy and debate about these public schools: Are they generally superior or inferior to other forms of public education? Are they cheaper or more expensive? Can the best ones be scaled-up without screwing-up the original excellence? Which charter school models are best and worst?

There is so much ideology and self-interest running through such debates that, despite some decent research, it is hard to answer such questions objectively. But one lesson is unfortunately becoming clear enough that there is growing agreement -- that my home state of California is so poor that it is a lousy place to start a Charter school of any kind. I first heard this a few weeks about from Anthony Bryk, a renowned educational researcher and the current President of the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. He was also directly involved in starting and running one (or perhaps more -- I don't recall for sure) charter schools when he lived in Chicago.

Tony told me that California was providing such meager funding that -- although much of the charter school movement started here, there are many charter schools here, and many of the organizations that start and run these schools (called "charter management organizations") are here -- the funding that California schools receive is so meager that they are increasingly hesitant to start schools in California because the schools are condemned to mediocrity or worse.

I started digging into it, and what I am finding is distressing as both a Californian and an American. I knew that our schools were suffering, but I did not realize how much. For a glimpse, here is an interesting and detailed article on scaling-up charter schools in Education Week from last year. As Tony warned me, the charter operators described in this article are struggling to sustain quality in California and are looking elsewhere. Here is an interesting excerpt:

Aspire, in Oakland, has also focused so far only on California. It opened its first charter school in Stockton, Calif., in the 1999-2000 school year and has grown by several schools each year. The CMO operates 30 schools and has nearly doubled its enrollment, to 12,000, over the past three school years. James Willcox, the chief executive officer of Aspire, said the difficult budget climate in California is causing him and other Aspire leaders to think about opening schools outside the state. “It’s getting harder and harder to do quality schools in California,” he said, “because the funding is so painfully low, and charter schools get less per student than traditional public schools.”

He isn't exaggerating. I was shocked to see, for example, that (according to the article) the State of California is currently providing less than $6000 per pupil each year; in contrast, New York City provides $13,500. Ouch. I know that government wastes lots of money, and certainly there are inefficiencies in education. But can we afford to do this our kids and our future? As Tony suggested, California has degenerated to the point where all they can do is support a teacher for every 30 kids or so, a tired old classroom and school, and little else.

I knew it was bad, but I didn't know it was this bad. There is plenty of blame to go around -- we all have our own pet targets -- but perhaps it is time to put our differences aside and do the right things.

July 17, 2012

Can You Handle the Mess?

Remember that speech from a Few Good Men where Jack Nicholson famously ranted at Tom Cruise "You can't handle the truth?" I was vaguely reminded of it when I saw this picture. It reminded me that, when it comes to creativity and innovation, if you want the innovations, money, and prestige it sometimes produces, you've get to be ready to handle the mess.

I love this picture because it is such a great demonstration that prototyping -- like so many other parts of creative process -- is so messy that it can be distressing to people with orderly minds. This picture comes from a presentation I heard at an executive program last week called Design Thinking Bootcamp.

It was by the amazing Claudia Kotchka, who did great things at VP of Design Innovation and Strategy at P&G -- see this video and article. She built a 300 person organization to spread innovation methods across the company. She retired from P&G a few years back and now helps all sorts of organizations (including the the Stanford d school) imagine and implement design thinking and related insights. As part of her presentation, she put up this picture from a project P&G did with IDEO (they did many). We always love having Claudia at the d.school because she spreads so much wisdom and confidence to people who are dealing with such messes.

That is what prototyping looks like... it even can look this messy when people are developing ideas about HR issues like training and leadership development and organizational strategy issues such as analyses of competitors.

July 6, 2012

Dysfunctional Internal Competition at Microsoft: We've seen the enemy, and it is us!

My colleague Jeff Pfeffer and I have been writing about the dysfunctional internal competition at Microsoft for a long time, going back to the chapter in The Knowing-Doing Gap (published in 2000) on "When Internal Competition Turns Friends Into Enemies." We quoted a Microsoft engineer who complained there were incentives NOT to cooperate:

"There are instances where a single individual may really be cranking and doing some excellent work, but not communicating…and working within the team toward implementation. These folks may be viewed as high rated by top management… As long as the individual is bonused highly for their innovation and gutsy risk-taking only, and not on how well the team accomplishes the goal, there can be a real disconnect and the individual never really gets the message that you should keep doing great things but share them with the team so you don’t surprise them."

And we quoted another insider who complained about the forced curve, or "stacking system:"

This caused people to resist helping one another. It wasn’t just that helping a colleague took time away from someone’s own work. The forced curve meant that “Helping your fellow worker become more productive can actually hurt your chances of getting a higher bonus.”

This downside of forced-rankings is supported by a pretty big pile of research we review in both both The Knowing-Doing Gap and in Hard Facts, and I return to a bit in Good Boss, Bad Boss. The upshot is that when people are put in a position where they are rewarded for treating their co-worker as their enemy, all sorts of dysfunctions follow. Forced rankings are probably OK when there is never reason to cooperate -- think of competitors in a golf tournament -- or perhaps when sales territories or (for truck drivers and such) routes can be designed so that people don't need to cooperate. And there is one trick I've seen used (at GE for example) where people are ranked, but part of the ranking is based on how much they help others succeed -- but people at GE have told me that forcing the firing of the bottom 10% can still create lots of problems (in fact, my understanding is that GE has softened this policy).

As my colleagues Jeff Pfeffer loves to say, the assumption that the bottom 10% have to go every year is really suspect -- it assumes a 10% defect rate! Imagine a manufacturing system where that was expected and acceptable:

Well, the Microsoft stacking system is in the news again. A story by Kurt Eichenwald in coming out in Vanity Fair that bashes Microsoft in various ways, especially the "stacking system." It is consistent with past research and reports that have been coming out of Microsoft for decades -- I bet I have had a good 50 Microsoft employees complain about the stacking the system to me over the years, including one of their former heads of HR.

The story isn't out yet, but according to Computerworld and other sources, this is among the damning quotes:

Every current and former Microsoft employee I interviewed -- every one -- cited stack ranking as the most destructive process inside of Microsoft, something that drove out untold numbers of employees. 'If you were on a team of 10 people, you walked in the first day knowing that, no matter how good everyone was, 2 people were going to get a great review, 7 were going to get mediocre reviews, and 1 was going to get a terrible review,' says a former software developer. It leads to employees focusing on competing with each other rather than competing with other companies.

To be clear, I am not opposed to pay for performance. But when unnecessary status are created, when small quantitative differences that don't matter are used to decide who is fired, anointed as a star, or treated as mediocre, and when friends are paid to treat each others as enemies, creating the unity of effort required to run an effective organization gets mighty tough -- some organizations find clever ways to get around the downsides of stacking, but some succeed despite rather than because of how they do it.

The late quality guru W. Edwards Deming despised force rankings. Let's give him the last word here. Here is another little excerpt from The Knowing-Doing Gap:

He argued that these systems require leaders to label many people as poor performers even though their work is well within the range of high quality. Deming maintained that when people get these unfair negative evaluations, it can leave them "bitter, crushed, bruised, battered, desolate, despondent, dejected, feeling inferior, some even depressed, unfit for work for weeks after receipt of the rating, unable to comprehend why they are inferior.”

July 5, 2012

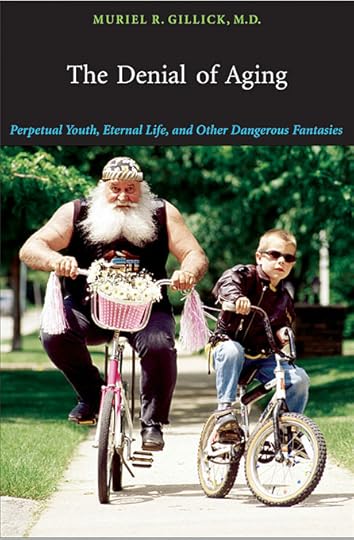

The Best Book Cover Ever? The Denial of Aging

I was exchanging emails with a Harvard University Press editor named Elizabeth Knoll and I commented that the cover of C.K. Gunsalus' The College Administrator's Survival Guide is one of the best I had ever seen. The designer, according the jacket cover is Jill Breitbarth. By the way, the contents of this Guide are also fantastic!

Well, when I mentioned how much I liked that cover, Elizabeth sent me a link to another Harvard cover, the amazing one above, which after some confusion (note this post is corrected), turns out to be by Gwen Nefsky Frankfeldt -- apparently now retired. I can't vouch for the book itself, but especially given the title, that might be the best book cover I have ever seen. I am 58 and there are times when feel like I am that guy with big white beard!

Tell me what you think, and if there is a cover you believe is even better, I would love to see it.

For fun, here is other cover I liked so much

July 3, 2012

Boring = Good? Inspirational = Bad?

That is the title of weird interview that just came out in INC this month, which I did with Leigh Buchanan. And the above drawing is by Graham Roumieu.

The story won't be on the INC website for a few weeks,it is only available in the print edition for now. But you can read it here.

Leigh is always fun to talk to, and after having done interviews on both The No Asshole Rule and Good Boss, Bad Boss, she has emerged as one of my favorite journalists. For starters, she has such a sense of fun -- most of us involved on doing and working with management are entirely too serious -- I certainly plead guilty. Leigh has the rare ability to talk about real ideas while at the same time conveying the absurdity of so much of organizational life . She is also a great editor. In every interview I have done with her, I've rambeled incoherently on for an hour or so, and she somehow put in a form that made sense.

This new interview a conglemeration of some of the stranger ideas from the various books I have written, especially Weird Ideas That Work along with some strange new twists. As with weird ideas , I offer these ideas to challenge your assumptions (and my own) and to prompt us all to think. I don't expect you to agree with them (I am npt even sure I agree with all of them), but there is actually a fair amount of evidence and theory to support each of these sometimes uncomfortable ideas.

To give you a taste,here is how the interview kicks-off:

Leigh: You and I have been e-mailing about leadership traits, and at one point you suggested, “Good leaders know when to be boring, vague, emotionally detached, and authoritarian.” Under what circumstances might such traits be desirable? Start with boring.

Me: There are two situations in which it’s a good idea to be boring. One is when you’re working on something but, so far, all you’ve got is bad news. Under those circumstances, any outside attention is bad.

Don Petersen was the CEO of Ford after the Iaccoca era, and he was responsible for turning the company around. He told me a story about being invited to speak at the National Press Club. He didn’t want to do it. At the time, Ford had no good cars at all. But he and his PR chief decided he would go and give a speech about the most boring subject they could think of. At the time, that was safety. He practiced speaking in the most boring way possible, using the passive voice and long sentences. He put up charts that were hard to read, and then turned his back to the audience to talk about the charts. After that, the press lost interest in him for a while, so he could concentrate on doing the work.

The other situation is when you’re dealing with controversy. Stanford used to have this brilliant provost, James Rosse. When Jim talked about something like the school’s Nobel Prize winners, he would be animated and exciting and charismatic. But when he had to talk about something like the lack of diversity on campus, he would ramble on for 20 minutes while looking at his feet. I thought it was brilliant

And so it goes. I hope you enjoy and I think Leigh for being such a delight to work with and for reminding me not to take myself so seriously.

July 2, 2012

Job Interview Advice: Go Heavy on the Perfume or Personal Charm, Not Both

I was interviewed this morning for a Woman's Day story on job interviews. As usual, just before talking with the journalist, I poked around peer-reviewed studies a bit. I found quite a few traditional ones, but there was one that was weird but rather instructive. It was a 1986 study by Robert Baron on the Journal of Applied Social Psychology. In brief, the design was that 78 subjects (roughly half men and half women) were asked to evaluate a female job candidate.

In one condition, she cranked-up the non-verbal charm, in the other she did not. As the article explains:

Specifically,she was trained to smile frequently (at prespecified points), to maintain a high level of eye contact with the subject, and to adopt an informal, friendly posture (one in which she leaned forward, toward the interviewer). In contrast, in the neutral cue condition she refrained from emitting any nonverbal behaviors. These procedures were adapted from ones employed in several previous studies (e.g., Imada & Hakel, 1977) in which nonverbal cues were found to exert strong effects upon ratings of strangers. Extensive pretesting and refinement were undertaken to assure that the two patterns would be distinct and readily noticed by participants in the present research.

In another condition, she wore perfume:

Presence or absence of artificial scent. In the scent present condition, the confederates applied two small drops of a popular perfume behind their ears prior to the start of each day’s sessions. In the scent absent condition, they didnot make use of these substances. (In both conditions, they refrained from employing any other scented cosmetics of their own.) The scent employed was “Jontue.” This product was selected for use through extensive pretesting in which 12 undergraduate judges (8 females, 4 males) rated 11 popular perfumes presented in identical plastic bottles. Judges rated the pleasantness of each scent and its attractiveness when used by a member of the opposite sex. “Jontue” received the highest mean rating among the female scents in this preliminary study.

The design was alternated so the subjects in different groups evaluated these imaginary job candidates with perfume or without, or with non-verbal charms or without, and researchers also examined the impact of having both perfume and charm, or neither. The results are pretty amusing but also useful. It turns out that having just perfume and just charm seemed to lead to high ratings by both male and female interviewers. BUT there was an interesting gender effect. The blend of both perfume and charm did not put-off female interviewers, but it did lead to lower evaluations for male interviewers.

This is just one little study, but it is amusing and possibly useful -- if you are woman and being interviewed by a guy, the blend of perfume and positive "non-verbals" might be too much of a good thing!

This is not a path-breaking study, but it is cute. And I it is interesting to know that Mae West sweet saying that " Too much of a good thing can be wonderful" has its limits!

P.S. Go here to see the complete reference and the abstract.

June 27, 2012

A Different Version of the Creation Myth

A big thanks to Carol Murchie for sending this my way.

June 16, 2012

Check-out J. Keith Murnighan's "Do Nothing" for Strange and Fact-Based Advice

Kellogg professor J. Keith Murnighan, my colleague and charming friend, has just published a lovely book called "Do Nothing." I first read the manuscript some months back (and thus could provide the praise you see on the cover) and I just spent a couple hours revisiting this gem.

This crazy book will bombard you with ideas that challenge your assumptions. His argument for doing nothing, for example, kicks-off the book. I was ready to argue with him because, even though I believe the best management is sometimes no management at all, I thought he was being too extreme. But as I read the pros and cons (Keith makes extreme statements, but his arguments are always balanced and evidenced-based), I became convinced that if more managers took this advice their organizations would more smoothly, their people would perform better (and learn more), and they would enjoy better work-life balance.

He convinced me that it this is such a useful half-truth (or perhaps three-quarters-truth) that every boss ought to try his litmus test: Go on vacation, leave your smart phone at home, and don't check or send any messages. Frankly, many bosses I know can't accomplish this for three hours (and I mean even during the hours they are supposed to be asleep), let alone for the three weeks he suggests. As Keith says, an interesting question is what is a scarier outcome from this experiment for most bosses: Discovering how MUCH or how LITTLE their people actually need them.

You will argue with and then have a tough time resisting Keith's logic, evidence, and delightful stories when it comes to his other bits of strange advice as well. I was especially taken with "start at the end," "trust more," "ignore performance goals," and "de-emphasize profits." Keith shows how the usual managerial approach of starting out relationships by mistrusting people and then slowly letting trust develop is not usually as beneficial as starting by assuming that others can be fully trusted until they prove otherwise. He will also show you how to make more money by thinking about money less!

As these bits suggest, Keith didn't write this book with the aim of telling most bosses what they wanted to hear. Rather his goal was to make readers think, to challenge their assumptions, and to show the way to becoming better managers by thinking and acting differently. In a world where we have thousands of business books published every year that all seem to say the same thing, I found Do Nothing delightful and refreshing -- not just because it is quirky and fun, but because Keith also shows managers how to try these crazy ideas in low-risk and sensible ways.

June 4, 2012

Total Institutions, Productivity, and Unemployment

This isn't an original idea, but it has been gnawing at me lately. As we all know, unemployment in the U.S. remains frighteningly high -- and is worse in many parts of Europe. We still haven't really dug our way out of the meltdown. At the same time, the hours worked by Americans remain incredibly high. See this 2011 infographic on The Overworked American. About a third of Americans feel chronically overworked. And some 39% of us work more than 44 hours a week.

I was thinking of this because I did an interview for BBC about Google -- you can see the piece here. I think it is done well and quite balanced. It shows all those lovely things they do at Google to try to make it so good that you never want to go home -- the classes, the great food, the laundry service, the massages and so on. And I do believe from many conversations with senior Google executives over the years that they care deeply about their people's happiness and well-being and seem -- somehow -- to have sustained a no asshole culture even at 32,000 people strong. That "don't be evil" motto isn't bullshit, they still mean it and still try to live it.

But as I said in the BBC piece, although they are more caring than many of their competitors, the result is that many great tech firms including Google border on what sociologist Erving Goffman called "total institutions." Examples of total institutions are prisons, mental institutions, the military (at least the boot camp part) -- places where members spend 100% of the time. The result is that, especially here in Silicon Valley, the notion of work-life balance is pure fiction most of the time (Sheryl Sandberg may go home at 530 every day, but the folks at Facebook did an all-night hack-a-thon right before the IPO. I love the folks at Facebook, especially their curious and deeply skilled engineers, but think of the message it sends about the definition of a good citizen in that culture).

To return to Google, about five years ago, one of the smartest and most charming students I ever worked with had job offers from two very demanding places: Google and McKinsey. Now, as most of you know, people work like dogs at McKinsey too. But this student decided to take the job at McKinsey because "My girlfriend doesn't work at Google, so if I take that job, I will never see her." He took the McKinsey job because at least that way he would see her on weekends. I am pleased to report that I recently learned that they are engaged, so I guess it was the right choice.

Note I am not blaming the leaders at Google, Facebook, or the other firms that expect very long hours out of their people. It is a sick norm that seems to keep getting stronger and seems to be shared by everyone around here -- indeed, my students tell me that they wouldn't want to work at a big tech firm or a start-up where people worked 40 hours a week because it would mean they were a bunch of lazy losers! I also know plenty of hardcore programmers who love nothing more than spending one long late night after another cranking out beautiful code.

Yet, I do wonder if, as a society, given the blend of the damage done by overwork to mental and physical health and to families, and given that so many people need work, if something can be done to cut back on the hours and to create more jobs. There are few companies that are trying programs (Check out the "lattice" approach at Deloitte). But it seems to me that we would all be better off if those of us with jobs cut back on our hours, took a bit less pay, and the slack could be used to provide the dignity and income that comes with work to all those people who need it so badly.

I know my dream is somewhat naive, and that adding more people creates a host of problems ranging from higher health care costs to the challenges of coordinating bigger groups. But in the coming decades, it strikes me as something we might work together to achieve. There are so many workplaces that have become just awful places because of such pressures to work longer and longer hours: large law firms are perfect example, they have become horrible places to work for lawyers at all levels. There is lots of talk of reform, but they seem to be getting worse and worse as the race for ever increasing billed hours and profits-per-partner gets worse every year. And frankly when I see what it takes to get tenure for an assistant professor at a place like Stanford, we are essentially expecting our junior faculty to work Google-like hours for at least seven years if they wish to be promoted, I realize I too am helping to perpetuate a similar system.

I would also note this is not just a "woman's issue." Or even a matter of structuring work so that both men and women can be around to raise their kids, as it sometimes is described. Sure, that is part of it. But I think that everyone could benefit from a change in such norms. Indeed, about five years ago, a managing partner of a large local law firm did a survey of attitudes toward part-time work and was surprised to learn that male associates who didn't have children were among the most enthusiastic supporters of part-time schedules. Interestingly, they were supportive partly because they couldn't use the "kid excuse" to cut back their hours and resented covering for colleagues who could and did leave work earlier and take days off to be with their children -- they resented having less socially acceptable reasons for cutting back days and hours.

What do you think? Is there any hope for change here? Or am I living in a fool's paradise?

Robert I. Sutton's Blog

- Robert I. Sutton's profile

- 266 followers