Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 27

October 16, 2015

October at Ingleside

“It would be terrible if we just skipped from September to November, wouldn’t it?” I, too, am “glad I live in a world where there are Octobers,” as Anne famously says to Marilla in Anne of Green Gables. I spent last weekend visiting Prince Edward Island with my family, rereading Anne of Ingleside for the first time in many years, and taking pictures, which was a lovely way to celebrate Canadian Thanksgiving. On Saturday, I caught the last of the day’s light on the hydrangeas and geraniums at L.M. Montgomery’s Birthplace Museum in New London.

Another highlight of the trip was an afternoon of reading Anne of Ingleside by the fire at Leonhards Café in Charlottetown. And of course I was particularly interested in what happens to Anne’s ambitions in this sixth book in the “Anne” series.

When I reread Anne’s House of Dreams, I was disappointed to find that Anne dismisses her writing and seems to have lost interest in the academic ambitions that were so important to her in the first four novels in the series. In Anne of Ingleside, it’s clear that the focus of her ambition is different. Like Edward Ferrars in Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Anne is ambitious about finding happiness, and in her life with Gilbert and their children at Ingleside, she seems to have found it. Mrs. Dashwood comments on Edward’s apparent lack of ambition, and he responds by saying his wishes are “As moderate as those of the rest of the world”: “I wish as well as every body else to be perfectly happy; but, like every body else it must be in my own way.”

Early in Anne of Ingleside, Gilbert asks, “Are you happy, Annest of Annes?” And she is. She’s delighted to be home again, and she feels “surrounded and encompassed by love.” She says “it’s been lovely to be Anne of Green Gables again for a week, but it’s a hundred times lovelier to come back and be Anne of Ingleside” (Chapter 3).

The house in Park Corner, PEI, that was the inspiration for Ingleside

She does talk a bit about her writing: when a neighbour asks her to write an “obitchery” for her late husband (“them things they put in the papers about dead people, you know”), Anne once again refers to her stories as “little.” In Anne’s House of Dreams she said, “I do little things for children”; here she says, “Occasionally I do write a little story,” adding that “a busy mother hasn’t much time for that,” and that “I never wrote an obituary in my life.” She acknowledges that she had “wonderful dreams once, but now I’m afraid I’ll never be in Who’s Who, Mrs. Mitchell” (Chapter 21).

I confess I felt a small shock of recognition when I read the chapter in which Christine Stuart, Gilbert’s former girlfriend, asks Anne what happened to her ambition. “You used to be quite ambitious, if I remember aright,” she says when they meet again near the end of Anne of Ingleside. But then Christine goes on to say things that are quite different from the questions I asked in last month’s blog post about Anne’s early plans for her writing and her education. “Didn’t you used to write some rather clever little things when you were at Redmond?” Christine asks. “A bit fantastical and whimsical, of course, but still…” (Chapter 40).

Like Mrs. Mitchell, who dismisses the obituary poem Anne writes as “real sprightly” but not “poetical” enough and tacks on an extra verse written by her “poetizing” nephew, Christine resembles the contemporary readers and critics who didn’t appreciate Montgomery’s work. In Magic Island: The Fictions of L.M. Montgomery, Elizabeth Waterston writes that after creating Anne, with her early ambition to become a writer, Sara Stanley, with a passion for storytelling so strong that she’s known as “The Story Girl,” and Emily Byrd Starr, with her goal of writing a diary “that it may be published when I die,” Montgomery was now “bitter enough about the writing life to debunk the whole business of writing” in Anne of Ingleside. Waterston says the “obitchery” incident “correlates with Montgomery’s disappointment when her erstwhile admirers in the Canadian Authors Association manoeuvred her out of a leadership position in the society.” Anne of Ingleside was published in 1939, long after all the other novels in the series, including Rainbow Valley and Rilla of Ingleside.

The more time I spend rereading these novels and dipping into the wealth of scholarly writing about them, the more I find myself thinking that the next time I reread the “Anne” books, I’ll read them in the order of publication, rather than in the order that corresponds to the ages of Anne and her children. So, next time: Anne of Green Gables (1908), Anne of Avonlea (1909), Anne of the Island (1915), Anne’s House of Dreams (1917), Rainbow Valley (1919), Rilla of Ingleside (1921), Anne of Windy Poplars (1936), and Anne of Ingleside (1939). Perhaps I’ll add Chronicles of Avonlea (1912), Further Chronicles of Avonlea (1920), and The Blythes Are Quoted (2009). But that’s a whole other topic – the continuing stories of the people whose lives intersect with those of Anne and her circle.

In Anne of Ingleside, Anne doesn’t find an audience that appreciates her writing, and the focus of her ambition has certainly changed. But she is very happy. There are references throughout the novel to her joy in the world in general and the world of Ingleside in particular, and after she clears up a misunderstanding with Gilbert, the novel ends with her laughter and delight in her marriage and her family. I was intrigued by the answer she gives when Christine asks her if she’s stopped writing, because in a twist on the idea of books as children – I’m thinking especially of Jane Austen referring to Pride and Prejudice as “my own darling Child” – Anne thinks of her children as stories, or letters.

Here’s her reply to Christine’s question about whether she’s given up writing: “‘Not altogether … but I’m writing living epistles now,’ said Anne, thinking of Jem and Co.” Christine doesn’t recognize the reference to the biblical passage about epistles “written not with ink, but with the Spirit of the living God,” from 2 Corinthians 3:3.

The New London sand dunes, in the distance

Anne finds happiness in her family and her island home. Fall is especially beautiful at Ingleside, with “the joy of winds blowing in from a darkly blue gulf and the splendor of harvest moons,” and “lyric asters in the Hollow and children laughing in an apple-laden orchard” (Chapter 11). One year, after Anne has recovered from a very bad case of pneumonia and the family is celebrating her return to health (Chapter 27), October is “a very happy month at Ingleside, full of days when you just had to run and sing and whistle” and “nights, with their sleepy red hunter’s moon,” that are “cool enough to make the thought of a warm bed pleasant.” The house “rang with laughter from dawn to sunset.”

Just before last Saturday’s sunset

Anne loves to work in her garden, “drinking in colour like wine” and “revelling in the exquisite sadness of fleeting beauty.” The colours of the season are vivid:

the blueberry bushes turned scarlet, the dead ferns were a rich red-brown, sumacs burned behind the barn, green pastures lay here and there like patches on the sere harvest fields of the Upper Glen and there were gold and russet chrysanthemums in the spruce corner of the lawn…. There was a reek of leaf fires all through the Glen, a heap of big yellow pumpkins in the barn, and Susan made the first cranberry pies.

There is plenty of sadness in this novel. At one point Gilbert has “an attack of influenza” that “almost ran to pneumonia” (Chapter 19), and young Walter whispers, “What will the world do if Father dies?” Anne’s illness is even more serious, and brings anxiety and fear and a “nameless shadow” to Ingleside (Chapter 25). The children don’t lose either of their parents, but they do have to deal with losing pets, along with many other challenges, including loneliness, bullying, betrayals, and existential questions such as what would happen if God “forgot to let the sun rise” (Chapter 19) and “what causes the cause?” Even at Ingleside, “nothing is ever quite perfect” (Chapter 27).

Gardens of Hope at the Prince Edward Island Preserve Company

And those beautiful Octobers are followed by Novembers, one of them particularly “dismal,” with “nothing but cold mist driving past or drifting over the grey sea beyond the bar. The shivering poplar trees dropped their last leaves. The garden was dead and all its colour and personality had gone from it … except the asparagus bed, which was still a fascinating golden jungle.” Montgomery’s description of weather in the Maritimes and Anne’s daughter Di’s response to it are all too familiar to me: “It rained … and rained … and rained. ‘Will the world ever be dry again?’ moaned Di despairingly” (Chapter 27).

But Anne and her oldest son Jem have planted tulip bulbs, which gives them the promise of “a resurrection of rose and scarlet and purple and gold in June.”

October 9, 2015

“Do not imagine, Miss Bennet, that your ambition will ever be gratified”

Lady Catherine insists to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice that she must not think she will ever improve her social status by marrying Mr. Darcy: “Do not imagine, Miss Bennet, that your ambition will ever be gratified.” From Lady Catherine’s insistence on thwarting what she perceives as Elizabeth’s ambition, to Mrs. Vernon’s fears in Lady Susan that Frederica will be “sacrificed to Policy and Ambition,” to Anne Elliot’s modest ambition in Persuasion to find “a small house in their own neighbourhood,” there is in Jane Austen’s novels an ongoing preoccupation with ambitious desires, whether those desires are focused on status and power or on the pursuit of more modest alternatives.

Lady Catherine insists to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice that she must not think she will ever improve her social status by marrying Mr. Darcy: “Do not imagine, Miss Bennet, that your ambition will ever be gratified.” From Lady Catherine’s insistence on thwarting what she perceives as Elizabeth’s ambition, to Mrs. Vernon’s fears in Lady Susan that Frederica will be “sacrificed to Policy and Ambition,” to Anne Elliot’s modest ambition in Persuasion to find “a small house in their own neighbourhood,” there is in Jane Austen’s novels an ongoing preoccupation with ambitious desires, whether those desires are focused on status and power or on the pursuit of more modest alternatives.

Over the past several months I’ve been writing about ambition in Austen’s works and in her life, and in June I spoke at a JASNA Eastern Pennsylvania meeting about the question of whether ambition is a vice or a virtue, and about what we can learn from Jane Austen as we try to come up with answers. I’m in the process of working out what I want to do next with this fascinating and controversial topic — which is to say, I’m trying to figure out whether I want to write blog posts, essays, and talks, or maybe someday a book. Whatever I decide, though, I do know that I want to explore the history of ambition further, especially in relation to Austen’s novels (and, as I mentioned here a few weeks ago, in relation to novels by L.M. Montgomery and Edith Wharton).

I’ve created a new page on my website to collect quotations about ambition and to keep track of the blog posts and essays I write about “Austen and Ambition.” I’ve also started to collect articles and images on an “Ambition” Pinterest board. I would love to hear your suggestions about characters who lack ambition or are said to have too much of it, and about passages in Austen (or elsewhere) that take up this question of whether ambition is good or bad.

This project is very much a work in progress and I’m looking forward to future conversations about the “elegant but ambitious” Caroline Simpson from Austen’s Jack and Alice, the “cold-hearted ambition” of Mary Crawford from Mansfield Park, the “ambitious & Insincere” Mr. Lushington mentioned in Austen’s letters, and the ambitious or unambitious desires of many others, including Fanny Price, of whom Mary Crawford says, “if there is a girl in the world capable of being uninfluenced by ambition, I can suppose it her.”

This project is very much a work in progress and I’m looking forward to future conversations about the “elegant but ambitious” Caroline Simpson from Austen’s Jack and Alice, the “cold-hearted ambition” of Mary Crawford from Mansfield Park, the “ambitious & Insincere” Mr. Lushington mentioned in Austen’s letters, and the ambitious or unambitious desires of many others, including Fanny Price, of whom Mary Crawford says, “if there is a girl in the world capable of being uninfluenced by ambition, I can suppose it her.”

I hope my own ambition to continue to find “good company and a great deal of conversation” will be gratified. I love talking about Austen (and Montgomery and Wharton and other writers) online and in person.

In 2016, I’ll be speaking on Austen and ambition at a JASNA Nova Scotia meeting, and I’m excited to share some new ideas I’ve been writing about in the months since my talk in Philadelphia. I’ll share more details once the date is confirmed.

Here’s the link to the new page, “Austen and Ambition.”

I’m also collecting images that appear in conversations about ambition: there’s “the bend in the road,” from Anne of Green Gables (with the imagined “new landscapes” and “new beauties” beyond), and the “alpine path” that L.M. Montgomery describes in her autobiography. I’d be glad to hear your suggestions about additional similes and metaphors. Ambition as a fire? Ambition and the danger of flying too close to the sun, perhaps?

September 29, 2015

Anne’s House of Dreams and the “great Canadian novel”

“Young Dr. Blythe” is a very busy man and he’s often away from the little white house he and Anne share near Four Winds Harbour at the start of their married life, but at least we do get to hear more about him in Anne’s House of Dreams. Anne says Gilbert is “hardly ever home except for a few hours in the wee sma’s. He’s really working himself to death. So many of the over-harbour people send for him now” (Chapter 22). His medical practice gets a great deal of attention in the second half of the novel, when he suggests to Anne that surgery might cure their neighbour Dick Moore’s “memory and faculties” (Chapter 29). I don’t know much about the procedure he recommends (and I’d be interested to read more about this aspect of the novel – let me know if you have any suggestions about essays on neurosurgery and the novels of L.M. Montgomery), but I have to say I did like the chapter in which “Gilbert and Anne Disagree,” because it brought back the antagonism that we first encountered in the infamous “Carrots” scene in Anne of Green Gables.

Back in May, I wrote about how disappointed I was that Gilbert was almost entirely absent from the story in Anne of Windy Poplars, the fourth book in L.M. Montgomery’s “Anne” series. I didn’t do a great job of keeping up with all the books in the “Green Gables Readalong” that Lindsey Reeder hosted from January to August this year, but I did read Anne’s House of Dreams in the late spring – and here I am now, writing about it in late September….

Here are just a few of the many other things I liked about Anne’s House of Dreams, in addition to the disagreement between Anne and Gilbert. I liked the way Montgomery explores Anne’s response to the sorrow that comes to her as a young wife and mother, and the way Anne’s marriage is contrasted with her neighbour Leslie’s in such a way that Anne realizes, even in the midst of that sorrow, just how fortunate she is. I liked the chapter (21) in which Leslie confesses to Anne that “there have been times this past winter and spring when I have hated you” and the two of them become close friends after they discuss the reasons for this hatred.

I liked the conversation Anne and Miss Cornelia have about obituaries: Miss Cornelia asks, “Have you ever noticed what heaps of good people die, Anne, dearie? It’s kind of pitiful. Here’s ten obituaries, and every one of them saints and models, even the men. Here’s old Peter Stimson, who has ‘left a large circle of friends to mourn his untimely loss.’ Lord, Anne, dearie, that man was eighty, and everybody who knew him had been wishing him dead these thirty years.” (This passage makes me think of what Jane Austen says to her sister Cassandra about their neighbour Mrs. Holder: “Only think of Mrs. Holder’s being dead! – Poor woman, she has done the only thing in the World she could possibly do, to make one cease to abuse her” [October 14, 1813].) Miss Cornelia thinks “obituary” is an ugly word. “There’s only one uglier word that I know of, and that’s relict. Lord, Anne, dearie, I may be an old maid, but there’s this comfort in it – I’ll never be any man’s ‘relict’” (Chapter 28).

Covehead Lighthouse, PEI

I did find it a bit hard to believe that in this small community, almost everyone Anne meets turns out to be a kindred spirit: Leslie (eventually), Miss Cornelia, the lighthouse keeper Captain Jim, and Owen Ford, the writer who comes to board at Leslie’s house for the summer. And while I remembered that Anne treasures her friendship with Captain Jim, I had forgotten the details of what he says about women writers. He’s pleased to find that Owen is “what he called a ‘real writing man’” and he’s quite ready to regard him as “a superior being” – superior, that is, to women who dare to write: he “knew that Anne wrote, but he had never taken that fact very seriously. Captain Jim thought women were delightful creatures, who ought to have the vote, and everything else they wanted, bless their hearts; but he did not believe they could write.” The reason he gives is that “A writing woman never knows when to stop; that’s the trouble. The p’int of good writing is to know when to stop.”

I agree with him about that very last bit. Good writing has as much to do with what you leave out and when you stop as with where you begin and what you put in. But I was disappointed to find that this so-called “kindred spirit” is so dismissive of Anne’s writing. And I was disappointed that Anne’s only response to what Captain Jim says here is to invite him to tell a story: “‘Mr. Ford wants to hear some of your stories, Captain Jim,’ said Anne. ‘Tell him the one about the captain who went crazy and imagined he was the Flying Dutchman’” (Chapter 24).

I had forgotten that in this book Anne herself is dismissive of her writing. Here’s the conversation she has with Owen when he first arrives and tells her he’s so impressed with the beauty of his temporary home that “if inspiration comes from beauty, I should certainly be able to begin my great Canadian novel here” (Chapter 23).

“You haven’t begun it yet?” asked Anne.

“Alack-a-day, no. I’ve never been able to get the right central idea for it. It lurks beyond me – it allures – and beckons – and recedes – I almost grasp it and it is gone. Perhaps amid this peace and loveliness, I shall be able to capture it. Miss Bryant tells me that you write.”

“Oh, I do little things for children. I haven’t done much since I was married. And I have no designs on a great Canadian novel,” laughed Anne. “That is quite beyond me.”

Owen Ford laughed too.

“I dare say it is beyond me as well. All the same I mean to have a try at it someday, if I can ever get time.”

Oh, Anne! What happened to “I’m just as ambitious as ever,” from that last chapter of Anne of Green Gables? “I do little things for children”? In her biography of Montgomery, Mary Rubio notes that “Less than three weeks after finishing Anne’s House of Dreams Maud began writing a version of her life called ‘The Story of My Career’ for publication in Everywoman’s World, a popular magazine for women.” Later published as The Alpine Path (1975), this story opens with a combination of modesty about her accomplishments – “Could my long, uphill struggle, through many quiet, uneventful years, be termed a ‘career’?” – and determination to succeed as a writer – Montgomery writes that to climb the path to “heights sublime” and “true and honoured fame” has been “the key-note of my every aim and ambition.” She was herself ambitious, and, as Rubio discusses in Chapter 19 of Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, her reputation suffered when she was “re-categorized as ‘a children’s writer’ and ‘provincial,’” after which “most male critics who belittled Maud’s books did not actually read them, they just accepted the labels pinned on them.”

I found it hard to believe that after all his struggles to write, Owen writes his “great Canadian novel” so quickly, in one summer, and then has “not much doubt that he would find a publisher.” He records the stories Captain Jim has been telling for years, and when he has completed the manuscript, “He knew that he had written a great book – a book that would score a wonderful success – a book that would live. He knew that it would bring him both fame and fortune” (Chapter 25). It’s all so easy! Soon the book is “heading the lists of the best sellers” (Chapter 40). It made me wonder why we don’t all try to write the great Canadian novel. But perhaps one has to be “a real writing man” to achieve that ambition.

In a way, I wish I hadn’t gone back to reread the later books in the “Anne” series, because when I was very young, the first books in the series inspired me to become a writer, and it’s been somewhat disappointing to find out what happens to Anne’s literary ambitions. But at the same time, it’s been fascinating to make comparisons with what I remembered from my childhood.

Forrest Building, Dalhousie University

When I read Anne of the Island as a child in Halifax, I didn’t realize Kingsport was based on the city I lived in, or that Redmond College was based on Dalhousie University, where my father was (and is) an English professor. Over the past couple of years I’ve enjoyed exploring Montgomery’s Nova Scotia connection in that novel and in her journals. (See “Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley” and “L.M. Montgomery in Nova Scotia.”) I had vague memories of disliking Anne of Windy Poplars when I was ten, but I had forgotten why, and when I reread it in April, I was interested to discover that immediately after Anne and Gilbert get engaged, he moves to the sidelines instead of continuing on as a central character in her story. (See “Anne and Gilbert After the Happy Ending.”) And I remember thinking it was quite magical that one of Anne’s closest friends in Anne’s House of Dreams was a lighthouse keeper, but I either didn’t notice Captain Jim’s dismissive attitude toward women and writing or I forgot about it over the years.

Eventually I’ll probably reread Anne of Ingleside, Rainbow Valley, and Rilla of Ingleside as well, even though I’ve missed the chance to blog about them in the appropriate months for this particular “readalong.” I’m especially interested in Rilla, and her preference for straight roads (as contrasted with her mother’s love of the “bend in the road”). At the moment I’m torn between thinking I ought to revisit the “Emily” series, which was also part of what inspired me at the ages of ten and eleven to want to be a writer, and thinking I just might want to hang onto my childhood memories of those books for a little longer.

September 18, 2015

Running in Halifax

I love thinking about the history of Halifax when I’m running. Long runs give me a chance to explore my city and take pictures of some of the places I’m interested in, including the Birch Cove estate where Lady Sherbrooke and her friend Mary Wodehouse read Mansfield Park in 1815, Point Pleasant Park, which helped L.M. Montgomery when she was homesick for Prince Edward Island, and the Public Gardens, which “are very beautiful just now” – which is true this month just as it was when Montgomery wrote this in her first column for the Halifax Daily Echo in September of 1901. Uniacke House, built between 1813 and 1815 (and just a short drive north of Halifax), also has some beautiful trails.

I love thinking about the history of Halifax when I’m running. Long runs give me a chance to explore my city and take pictures of some of the places I’m interested in, including the Birch Cove estate where Lady Sherbrooke and her friend Mary Wodehouse read Mansfield Park in 1815, Point Pleasant Park, which helped L.M. Montgomery when she was homesick for Prince Edward Island, and the Public Gardens, which “are very beautiful just now” – which is true this month just as it was when Montgomery wrote this in her first column for the Halifax Daily Echo in September of 1901. Uniacke House, built between 1813 and 1815 (and just a short drive north of Halifax), also has some beautiful trails.

Bluenose II, passing Georges Island

Here are a few pictures of the places where I ran this summer, when I was training for my third half marathon at Maritime Race Weekend. Please let me know if you have suggestions about parks and trails worth visiting, whether they’re in Nova Scotia or in other parts of the world. I love to run when I’m travelling.

Race day last Saturday was fantastic, with some beautiful fog at the beginning of the race and a beautiful absence of rain all morning (after a downpour overnight). I ran without stopping, and I didn’t take a single picture that day, even though I was tempted by the magnificent views of Devil’s Island. Perhaps I’ll go back to the course sometime just to take photos.

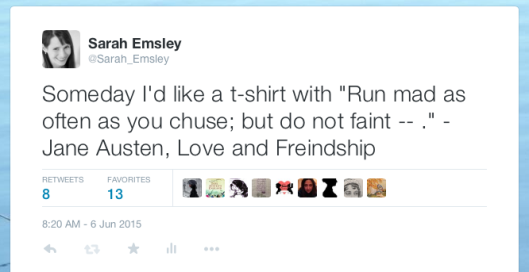

Following advice from Jane Austen’s Love and Freindship, I ran mad and didn’t faint. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience and I’m already thinking about registering for my fourth half marathon. If you read last week’s blog post, you know already that I like to focus on what I’m seeing and how I’m feeling, more than on how fast I’m going (although sometimes, I confess, it’s also fun to challenge myself to run faster).

C.S.S. Acadia, Maritime Museum of the Atlantic, Halifax waterfront

Theodore Tugboat, Halifax waterfront

Belcher’s Marsh Park, part of the Birch Cove estate Sir John and Lady Sherbrooke leased from Halifax merchant Andrew Belcher when they were in Halifax, between 1811 and 1816.

There are more pictures of Belcher’s Marsh Park in the article my friend Sheila Johnson Kindred and I wrote last year, published in Persuasions On-Line 35.1: “Among the Proto-Janeites: Reading Mansfield Park for Consolation in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1815.”

The Old Post Road, Uniacke House

Black Rock Beach, Point Pleasant Park

Halifax Public Gardens

You can’t run in the Gardens – though Lezlie Lowe made the case for changing that rule – but it’s a beautiful place to walk after a long run, especially at the end of August and the beginning of September, when the dahlias are in bloom.

(In The Lucy Maud Montgomery Album, compiled by Kevin McCabe and edited by Alexandra Heilbron [1999], Carol Dobson quotes the line from Montgomery’s September 28, 1901 column for the Daily Echo.)

September 8, 2015

Reading, Writing, Running

Today is my birthday, and I’m planning to celebrate by reading the last chapter of Jane Austen’s Emma early this morning (part of the preparations for my upcoming blog series celebrating 200 years of Emma), by running for about half an hour (part of my training for the half marathon I’m registered for on Saturday), and by writing for the rest of the day before celebrating with my family this evening. I haven’t decided yet what I’ll write about – probably I’ll wait until I’m running to make that decision. I make a lot of decisions when I’m running, and quite often they’re about which writing or editing projects I want to pursue, either that day or in the future, or about what to read next, or about details I’ve been puzzling over in a particular piece I’m working on. For example, I was inspired to start writing the first draft of this blog post while I was running indoors on a track on a rainy day. Do any of you come up with new ideas for reading and writing while you’re exercising? I’d be interested to hear about your experiences.

I didn’t discover running until I was in grad school, and sometimes I envy my sister, who discovered it when she was nine – and hasn’t looked back since. But I feel grateful that I discovered writing when I was very young, starting a diary when I was eight and deciding soon afterwards that I wanted to be a writer when I grew up, and that my parents helped me discover reading long before that.

My first two diaries

(It was fun to go back to my first two diaries and see what I was reading when I was eight: The Trumpet of the Swan, Superfudge, Deenie, The Secret Garden, Ballet Shoes, Anne of Green Gables, The Cuckoo Clock. One morning I woke up at four o’clock and couldn’t get back to sleep, so I read an abridged version of George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda, which I didn’t understand at all. I loved the book when I reread it – unabridged, of course – twenty years later.)

I’ve been thinking for several years about how important reading, writing, and running are to me, and two things I’ve read recently have helped me see the connections among them more clearly. The first is my friend Renée Hartleib’s meditation on the joy of running. In a blog post called “It is solved by running,” she notes that her “energy is at its highest” and her “mind is at its clearest” when she’s active, and she talks about running as a “revelation” and a “reawakening.” I love the way she describes her recurring dream about running so quickly and confidently that it’s almost as if she’s flying. I know exactly what she means about how running brings with it more energy and a clearer mind, both of which make it easier and more fun to write – and to live.

The second is Haruki Murakami’s book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which he says, “Most of what I know about writing I’ve learned through running every day.” He asks:

The second is Haruki Murakami’s book What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, in which he says, “Most of what I know about writing I’ve learned through running every day.” He asks:

How much can I push myself? How much rest is appropriate – and how much is too much? How far can I take something and still keep it decent and consistent? When does it become narrow-minded and inflexible? How much should I be aware of the world outside, and how much should I focus on my inner world? To what extent should I be confident in my abilities, and when should I start doubting myself? (Chapter 4)

I’ve learned a great deal about running and writing from asking myself similar questions, always in search of the appropriate balance between effort and rest. I’ve also learned from Aristotle, whose writing about ethics teaches me the value of the process of becoming virtuous, of becoming better in some way, which can apply to physical strength as well as to moral character. And I’ve learned from Jane Austen (you knew that was coming, right?), whose novels illuminate for me this Aristotelian approach to virtue and vice. Years of writing about Austen and Aristotle have taught me the value of working towards strength – moral, intellectual, physical – while acknowledging that there will never be a point at which I can say, “I’ve got it exactly right this time, and I don’t need to do any more.” I will always need to keep moving, to keep running, to keep thinking, to keep writing and revising, and to do all of that, I need to read – widely, often, and with enthusiasm and curiosity.

I like what Matthew Arnold says in the preface to Culture and Anarchy (1869) about the importance of reading: “a man’s life of each day depends for its solidity and value on whether he reads during that day, and, far more still, on what he reads during it.”

like what Matthew Arnold says in the preface to Culture and Anarchy (1869) about the importance of reading: “a man’s life of each day depends for its solidity and value on whether he reads during that day, and, far more still, on what he reads during it.”

And I like what Mr. Darcy says in Pride and Prejudice about how he “cannot comprehend the neglect of a family library in such days as these” (Chapter 8). (Poor Miss Bingley, whose father has “left so small a collection of books.” My bookseller friends will attest to my efforts to follow Mr. Darcy’s advice and pay close attention to my family library. Quite often my days consist of reading, writing, running, and book-buying. Or library-going.)

The half marathon I plan to run on Saturday will be my third. The first one was in 2013 and the second was last year, all at this same race in Halifax, Maritime Race Weekend. I’m starting to think of it as my new birthday tradition, along with a tradition of making a donation to an institution or charity that supports literacy – because September 8th is International Literacy Day. (Now that’s the kind of “birthday coincidence” I really like! Although if you have birthdays in August or October, dear readers, I will, like Anne of Green Gables, happily celebrate that “coincidence” too.)

Maritime Race Weekend is held at Fisherman’s Cove. The ocean views on the half marathon route are stunning, and last year I was very tempted to take pictures along the way – something I love to do on training runs – but I resisted and took this picture after I had finished the race.

This year, I almost gave up on half marathon #3, because while I liked the idea of my new tradition very much, in the spring my hip was bothering me and I wasn’t running as much as I did last year or the year before when I prepared for longer distances. I considered deferring my registration to 2016, and wondered, with Murakami, “How much rest is appropriate – and how much is too much?” I didn’t want to push myself to the point at which I might get a serious injury, but I didn’t want to back out if I didn’t really need to. (As Henry Tilney says in Northanger Abbey, “When properly to relax is the trial of judgement” [Chapter 16].) At the beginning of July, with a new training plan from my sister and encouragement from family and friends, many of whom are experienced runners, I decided to train for this half marathon.

I’m glad I let go of the feeling that I ought to be able to run faster than I did last year or the year before. On training runs I paid more attention to what I was seeing and to how I was feeling than to how fast I was going. There are so many beautiful trails in Nova Scotia, and I enjoyed exploring some of them this summer, including the Old Post Road at Uniacke House.

Uniacke House

When it came time for the longest training run of the summer, I happened to be in southern Alberta, and I loved running for a couple of hours on a cool August morning down a prairie road that I’ve known since childhood.

I did have to add some extra hill training when I got back to Nova Scotia.

I’m now feeling very excited about celebrating my birthday by running for 13.1 miles. Someday, I might like to run a marathon, but even if I do reach that goal, I’ll know that I’ve celebrated the process all along the way.

And someday perhaps I’ll write more about running and setting goals in relation to my new favourite topic, ambition. My interest in L.M. Montgomery’s phrase “the bend in the road” is also linked to my passion for running. I have lots of ideas for future books and essays and blog posts, but even while I’m aiming for specific writing goals, I’m committed to enjoying the energy and clarity that I get from reading, writing, and running pretty much every day.

And on days when I don’t really feel like writing or running, when I don’t have that “almost-flying” feeling Renée describes – and there are plenty of them, as I expect there are for most writers and runners – I’m going to keep reminding myself of what Jane Austen says about being a reluctant writer: “I am not at all in a humour for writing; I must write on till I am” (from a letter to her sister Cassandra, October 26, 1813). If I am not in a humour for running, I must keep running until I am. I might even run mad as often as I choose, but I’ll take care not to faint.

August 28, 2015

Anne Shirley’s Ambitions

I’ve always loved the image of the “bend in the road” that appears in the final chapter of L.M. Montgomery’s Anne of Green Gables. Anne’s plans for the future change, and while she can’t quite see what’s ahead of her on that road, she’s ready to move forward with confidence to embrace the unknown. I thought about this passage last summer when I found Montgomery had pasted into her Red Scrapbook a Notman Studio photograph of a bend in the road at Point Pleasant Park.

Warburton Road

Imagine my delight when I looked up the passage from that last chapter of Anne of Green Gables once again and discovered that in addition to talking about making peace with the mysteries of the future, Anne talks about her ambitions. She tells Marilla she’s decided to stay at home with her so they won’t have to give up Green Gables:

“Nothing could be worse than giving up Green Gables – nothing could hurt me more. We must keep the dear old place. My mind is quite made up, Marilla. I’m NOT going to Redmond; and I AM going to stay here and teach. Don’t you worry about me a bit.”

“But your ambitions – and – ”

“I’m just as ambitious as ever. Only, I’ve changed the object of my ambitions. I’m going to be a good teacher – and I’m going to save your eyesight. Besides, I mean to study at home here and take a little college course all by myself. Oh, I’ve dozens of plans, Marilla. I’ve been thinking them out for a week. I shall give life here my best, and I believe it will give its best to me in return. When I left Queen’s my future seemed to stretch out before me like a straight road. I thought I could see along it for many a milestone. Now there is a bend in it. I don’t know what lies around the bend, but I’m going to believe that the best does. It has a fascination of its own, that bend, Marilla. I wonder how the road beyond it goes – what there is of green glory and soft, checkered light and shadows – what new landscapes – what new beauties – what curves and hills and valleys further on.”

– From Chapter 38, “The Bend in the Road”

If you’ve been following my blog for a while, you’ll know that I’ve been getting more and more interested in the topic of ambition in relation to Jane Austen’s life and works. I had forgotten that Marilla and Anne use that term when Anne talks about the bend in the road. So now, of course, I’m inspired to explore what Montgomery says about ambition elsewhere in her novels, alongside my research on “Austen and Ambition.” I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on either of these writers – or my other favourite author, Edith Wharton – and the things they say about ambition in their fiction and letters. I’m curious to find out more about this topic and I’ll keep you posted as my “dozens of plans” take shape.

August 14, 2015

“It’s good to be alive and to be going home”

In Anne of Green Gables, after a trip to Charlottetown, Anne and Diana return home to Avonlea along the north shore of Prince Edward Island:

Anne and Diana found the drive home as pleasant as the drive in – pleasanter, indeed, since there was the delightful consciousness of home waiting at the end of it. It was sunset when they passed through White Sands and turned into the shore road. Beyond, the Avonlea hills came out darkly against the saffron sky. Behind them the moon was rising out of the sea that grew all radiant and transfigured in her light. Every little cove along the curving road was a marvel of dancing ripples. The waves broke with a soft swish on the rocks below them, and the tang of the sea was in the strong, fresh air.

“Oh, but it’s good to be alive and to be going home,” breathed Anne.

– From Chapter 29, “An Epoch in Anne’s Life”

A few weeks ago, when I visited the Island with my family, we drove from Charlottetown back to our friends’ cottage one evening after dinner, stopping at the beaches at Dalvay and Stanhope to admire and photograph the spectacular sunset. It was good to be alive.

Dalvay Beach

Stanhope Beach, a few minutes later.

July 29, 2015

Five Years!

Jane Austen’s letters, her novels Emma and Persuasion, the virtue of charity, the history of Nova Scotia, and the composition of Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country: these topics and other favourites appear right from the beginning, in the first few posts I wrote when I launched this blog in the summer of 2010. It’s hard to believe five years have gone by since then (and, given my later obsession with Mansfield Park, it’s hard to believe there was no mention of it at all in those early posts).

Thank you for reading the blog and for writing comments and guest posts. It’s been a real pleasure to create a place for “good company and a great deal of conversation” and I’m looking forward to future conversations with all of you!

To celebrate the five-year anniversary of my blog, I’ve put together a list of the first five posts, plus the five most popular posts and five of my own favourites. If you’d like to read each post in its entirety, click on the title.

The first five:

The first five:

“‘I do not mean to take any other exercise, for I feel a little tired after my long Jumble.’ Jane Austen was writing to her sister Cassandra after the journey to her brother Henry’s house in London. I love the idea of a long, tiring road trip as a ‘jumble’….”

French Fact and American Fiction

French Fact and American Fiction

“Edith Wharton was in the process of moving to France during the years she worked on The Custom of the Country, which makes me wonder if her increasing affection for France and her attempts to distance herself from her American life prompted her to fictionalize – and satirize – American places while implying that there was something more ‘real’ about France….”

“The other day, on a sunny summer afternoon when I was picking blueberries in the Annapolis Valley, I happened to overhear a conversation about Emma and Mr. Knightley. A couple of rows over (these were high bush blueberries), one woman was telling another about the scene on Box Hill, describing how Emma insults Miss Bates and how Mr. Knightley tells her that what she has said was ‘badly done.’ For a moment I felt like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, overhearing a conversation that interests her from behind the hedgerow….”

“The other day, on a sunny summer afternoon when I was picking blueberries in the Annapolis Valley, I happened to overhear a conversation about Emma and Mr. Knightley. A couple of rows over (these were high bush blueberries), one woman was telling another about the scene on Box Hill, describing how Emma insults Miss Bates and how Mr. Knightley tells her that what she has said was ‘badly done.’ For a moment I felt like Anne Elliot in Persuasion, overhearing a conversation that interests her from behind the hedgerow….”

Mr. Lushington and the Franfraddops

“I think one of the reasons Austen is so good in her novels at dramatizing the problem of how to speak and act in a charitable manner is that she knows all too well the very human temptation to speak ill of others….”

“The town of Annapolis Royal is celebrating its 300th anniversary this year, and when I was there I was thinking about how different the history of Nova Scotia would be if Annapolis Royal had remained the capital of the province, as it was from 1710 to 1749, before Halifax was founded….”

The five most popular:

Jane Austen’s “Darling Child” Meets the World

Jane Austen’s “Darling Child” Meets the World

“Jane writes to her sister Cassandra that she’s grateful for Cassandra’s praise of the novel because she has been having ‘some fits of disgust’ recently. She is at home in Chawton without Cassandra, keeping the secret of her authorship from her neighbours and enduring the irritation of listening to her mother’s interpretation of her characters….”

Your Invitation to Mansfield Park

“The party begins on Friday, May 9th, with Lyn Bennett’s thoughts on the first paragraph, followed in the next few weeks by Judith Thompson on Mrs. Norris and adoption, Jennie Duke on Fanny Price at age ten (‘though there might not be much in her first appearance to captivate, there was, at least, nothing to disgust her relations’), Cheryl Kinney on Tom Bertram’s assessment of Dr. Grant’s health (‘he was a short–necked, apoplectic sort of fellow, and, plied well with good things, would soon pop off’), and Katie Davis on Mrs. Grant’s promise to Mary and Henry Crawford that ‘Mansfield shall cure you both’….”

“The party begins on Friday, May 9th, with Lyn Bennett’s thoughts on the first paragraph, followed in the next few weeks by Judith Thompson on Mrs. Norris and adoption, Jennie Duke on Fanny Price at age ten (‘though there might not be much in her first appearance to captivate, there was, at least, nothing to disgust her relations’), Cheryl Kinney on Tom Bertram’s assessment of Dr. Grant’s health (‘he was a short–necked, apoplectic sort of fellow, and, plied well with good things, would soon pop off’), and Katie Davis on Mrs. Grant’s promise to Mary and Henry Crawford that ‘Mansfield shall cure you both’….”

Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive? (and of course the reasons for the popularity of this post are totally mysterious to me)

Why is Mr. Darcy So Attractive? (and of course the reasons for the popularity of this post are totally mysterious to me)

“We now live in a world that relies heavily on visual images, which is part of why ‘Colin Firth in a wet shirt’ signifies passion and desire in Pride and Prejudice. Yet in the novel, Austen makes clear that this moment is significant not because Elizabeth is looking at Darcy and admiring his handsome face or figure, but because there is such a strong connection between the two of them already that ‘their eyes instantly met,’ and they simultaneously blush at meeting in such circumstances. They’re looking at each other. It isn’t that the heroine and readers or audience are gazing at Darcy….”

Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley

Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley

“Redmond College is based on Dalhousie University and the ‘quaint old town’ of Kingsport described in Anne of the Island is based on Halifax….”

Clarity and Complexity: Mansfield Park Begins

“Happy 200th anniversary to Mansfield Park, published on this day in 1814. Mansfield Park is not as famous as Jane Austen’s ‘darling child’ Pride and Prejudice, but it’s still beloved, and the celebrations are just beginning. … I’m very happy to introduce Lyn Bennett’s guest post on the opening paragraph of Mansfield Park….”

Five of my own favourites:

“Jane Austen thought of her books as her children. Pride and Prejudice, which she called ‘my own darling Child,’ was sold to Thomas Egerton in November 1812. Two hundred years ago today, Jane wrote to her friend Martha Lloyd that ‘P. & P. is sold.—Egerton gives £110 for it.—I would rather have had £150, but we could not both be pleased, & I am not at all surprised that he should not chuse to hazard, so much’….”

Mansfield Park is a Tragedy, Not a Comedy

“Many readers find the ending of Mansfield Park disappointing. I think that’s because most of us tend to approach Austen novels with the expectation that they will be romantic comedies. And most of them are. But not this one….”

“Many readers find the ending of Mansfield Park disappointing. I think that’s because most of us tend to approach Austen novels with the expectation that they will be romantic comedies. And most of them are. But not this one….”

What Edith Wharton Tells Us About the Way We Live Now

“Wharton’s criticism of materialism, cultural ignorance, and the dangers of extreme versions of Emersonian self-reliance is more relevant than ever….”

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

L.M. Montgomery’s Literary Pilgrimage to Concord, Mass.

“Given how many fans of L.M. Montgomery visit ‘Green Gables’ in Cavendish, PEI each year, I find it fascinating to read about Montgomery’s own literary pilgrimage to Concord, Massachusetts, when she was visiting her publisher, L.C. Page in Boston in November of 1910. ‘Concord is the only place I saw when I was away where I would like to live,’ she writes….”

“‘Happy for all her maternal feelings was the day on which Mrs. Bennet got rid of her two most deserving daughters.’ The opening line of the last chapter of Pride and Prejudice is my favourite line in the novel because it’s the only mention of the wedding day for Elizabeth and Darcy, and Jane and Bingley. I like it because the focus on Mrs. Bennet’s attitude toward weddings ties the ending of the novel to the beginning, because the sentence is short and snappy, and because this line challenges the expectations of readers who come to the novel expecting a big wedding as the culmination of the courtship plot. There’s no question that Pride and Prejudice has a happy ending — but the wedding day isn’t the most important part of the happy ending….”

Thanks again to all of you for being part of the conversations and celebrations here!

July 18, 2015

“We must think the best”

“We must think the best & hope the best & do the best.” Jane Austen wrote this line in a letter to her sister Cassandra on November 26, 1815, when their brother Henry was very ill, and I’ve returned to it many times over the years that I’ve been studying her life and letters. Henry has been hoping he’ll be able to travel to Oxford for a few days, but although he “gets out in his Garden every day … at present his inclination for doing more seems over” and “his feelings are for continuing where he is, through the next two months.” “One knows the uncertainty of all this,” Jane acknowledges, “but should it be so, we must think the best & hope the best & do the best.”

This is not the “syringa, iv’ry pure” of Cowper’s line, but I thought it was pretty anyway. “I could not do without a Syringa, for the sake of Cowper’s Line” (Jane to Cassandra, February 8 and 9, 1807)

She tells Cassandra that “Henry calls himself stronger every day & Mr. H. keeps on approving his Pulse – which seems generally better than ever – but still they will not let him be well. – The fever is not yet quite removed. – The Medicine he takes (the same as before you went) is cheifly to improve his Stomach, & only a little aperient. He is so well, that I cannot think why he is not perfectly well.”

She was determined to be optimistic in the face of death, just as she was eighteen months later after Henry had recovered and she herself was ill. She wrote to her friend Anne Sharp on May 22, 1817 that while “inspite of my hopes & promises when I wrote to you I have since been very ill indeed,” “Now, I am getting well again, & indeed have been gradually tho’ slowly recovering my strength for the last three weeks. I can sit up in my bed & employ myself, … & really am equal to being out of bed, but that the posture is thought good for me.” She was so well, it seems, that she could not think why she was not perfectly well.

Later in that same letter to Miss Sharp there’s another example of her “thinking the best.” She’s grateful for the kindness of those who are caring for her, and she concludes, “In short, if I live to be an old Woman I must expect to wish I had died now, blessed in the tenderness of such a family, & before I had survived either them or their affection.”

Jane Austen died 198 years ago today, on July 18, 1817.

I mentioned a few weeks ago that I was entertained by the only line in her letters in which she explicitly mentions her ambition: “I wore my Aunt’s gown & handkercheif, & my hair was at least tidy, which was all my ambition” (from a letter she wrote to Cassandra on November 20 and 21, 1800). I like the idea of putting this ironic line together with her more serious ambition to “think the best & hope the best & do the best.” What should we aim for, in ordinary life or under extraordinary duress? “The best.”

Quotations are from the fourth edition of Jane Austen’s Letters, edited by Deirdre Le Faye (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011).

July 3, 2015

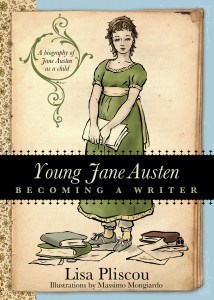

Imagining Jane Austen’s Childhood

“But history, real solemn history, I cannot be interested in … a great deal of it must be invention,” says Catherine Morland in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. In Young Jane Austen: Becoming a Writer, Lisa Pliscou cites Catherine’s words as inspiration for her “speculative biography” of the period from Austen’s birth to the age of twelve, when she began to focus on writing stories. Lisa knows about my interest in introducing Jane Austen to children, so she sent me a copy of her new book, and I’m glad she did because I had heard about it and I was curious to read her version of Austen’s early years. Noting that few facts are known about this period and acknowledging that she risks satisfying “neither the most stringent biographer nor the reader anticipating a great deal of dialogue and description,” Lisa offers an imaginative recreation of Jane Austen’s childhood.

A series of brief meditations on such topics as “Home,” “Play,” “Evening,” “Leaving Home,” “School,” and “Cousin Eliza” illuminate crucial moments in Austen’s childhood – such as the transitions from the Austen family home to her foster home in the village of Steventon and, later, to Mrs. Cawley’s school in Oxford and the Abbey School in Reading – and highlight important aspects of daily life in the Austen family, including helping with chores, listening to others read books and newspapers aloud, attending church services, and playing outdoors.

The thread that connects all the pieces of the story is a question Jane Austen must have returned to again and again: what opportunities are open to girls? This was an excellent question in the late eighteenth century and it’s an excellent question now. Lisa draws attention to possible answers throughout her book. In the section on “Play” she writes, “You could go to the big barn and pretend you were a king or a monster or a sailor or a tossing ship, and be as loud as you liked – even if you were a girl.” She imagines young Jane watching as her brothers’ lives took shape – James studying, Edward travelling, George being sent away because he had fits and could not speak or hear – and coming to the realization that “Home was not a place where you stayed forever.”

Jane’s older brother James was known as “the writer in the family,” after Mrs. Austen’s assessment of his talents, and Lisa explores what Jane might have thought about that label. It’s easy to imagine her wondering whether there could be more than one writer in a family, especially given that Mrs. Austen wrote letters and verses and Mr. Austen wrote letters and sermons. Young Jane – Lisa calls her Jenny, the nickname her father gave her when she was born – is a reader, and she interprets the world around her as if it is a story. When her sophisticated cousin Eliza comes to visit, Lisa says, “To Jenny it seemed as if Eliza had stepped straight from the pages of a book.” Jane is fascinated by books about people, especially “awful old Queen Elizabeth,” “poor Mary Stuart,” and heroines whose “saintly goodness” is amusing, and she is curious about books that tell young ladies how they ought to behave. “What could a girl do?”

Lisa suggests that the questions Jane Austen asked as a young child led her to the realization that she could do something exciting with words and stories. At the end of Young Jane Austen, “Jenny – Jane – picked up her pen, and began to write.”

This moment is only the beginning of Jane Austen’s development as a writer, of course, and in fact it isn’t the end of this biography either. The book doesn’t take up the question of what Austen wrote as a child; instead, the second half of the book repeats the story from birth to age twelve, this time with annotations instead of illustrations. The first half of the book will be especially appealing to young readers, with Massimo Mongiardo’s delightful sketches of Jane, her family, and her home. The second half of the book will be of interest to older readers who want to know about the sources Lisa has drawn on in imagining Jane’s early years.

At first I was somewhat surprised at the way the book is organized – the second part repeats the text of the first part, in addition to providing notes. But I think the division and repetition are quite helpful. Younger readers can ignore the second half if they wish, while those who want to read the details in that section won’t find themselves flipping back and forth between text and endnotes.

I think Young Jane Austen is a charming book, of interest to readers of all ages in its imaginative retelling of central events in Austen’s life and its exploration of questions over which she must have puzzled. I have two main criticisms to offer. One is the overuse of italics – I think L.M. Montgomery’s Mr. Carpenter is right when on his deathbed he advises Emily Starr to “Beware – of – italics” in her writing (in Emily’s Quest). The other is that I wish the book continued beyond the point at which Austen began to write. I would have liked to hear more commentary on the development of Austen’s juvenilia.

But that is a separate topic, and one Juliet McMaster addresses in her own new book, Jane Austen, Young Writer, forthcoming later this year from Ashgate. Juliet’s book is based on her years of research on the juvenilia: she founded the Juvenilia Press and has edited many of Jane Austen’s youthful writings, including The Beautifull Cassandra, which is one of my favourites. (She also wrote a guest post for my Mansfield Park celebrations last year.) Young Jane Austen and Jane Austen, Young Writer are very different, but for many readers – admittedly not the younger readers for whom Lisa’s book will be an introduction to Austen’s early life – they will be complementary.

But that is a separate topic, and one Juliet McMaster addresses in her own new book, Jane Austen, Young Writer, forthcoming later this year from Ashgate. Juliet’s book is based on her years of research on the juvenilia: she founded the Juvenilia Press and has edited many of Jane Austen’s youthful writings, including The Beautifull Cassandra, which is one of my favourites. (She also wrote a guest post for my Mansfield Park celebrations last year.) Young Jane Austen and Jane Austen, Young Writer are very different, but for many readers – admittedly not the younger readers for whom Lisa’s book will be an introduction to Austen’s early life – they will be complementary.

Read more about introducing children to Jane Austen’s life and works on my page “Jane Austen for Kids.”