Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 30

November 21, 2014

Austen’s Sirens

Twenty-ninth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I first met Sharon Hamilton at the University of Alberta when I was an undergraduate, and later connected with her again at Dalhousie University, where she was working on her Ph.D. in English when I began my master’s degree. I remember the exact moment at which we discovered our shared love of Jane Austen – at a dinner celebrating the birthday of a mutual friend – and Sharon exclaimed, “You’re a Janeite, too!” Sharon and I also share a love of Prince Edward Island’s landscape and beaches as well as its literature.

Dalvay Beach, PEI

Sharon is a writer and researcher who divides her time between Ottawa, Ontario and Spring Brook, PEI. She specializes in American literature and she has published and given lectures on the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Ernest Hemingway, H.L. Mencken, Emily Dickinson, Willa Cather, and many other writers. Her essay “Teaching Hemingway’s Modernism in Cultural Context: Helping Students Connect His Time to Ours” will be published next year in Teaching Hemingway and Modernism, edited by Joseph Fruscione (Kent State University Press). Her guest post on Mansfield Park is partly inspired by her response to the post Juliet McMaster wrote in the summer for this series, “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?”

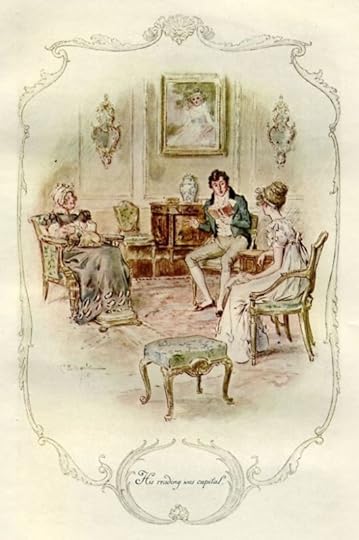

“His reading was capital.” Illustration by C.E. Brock. (http://www.mollands.net/etexts/mansfieldpark/mpillus.html)

Edmund watched the progress of her attention, and was amused and gratified by seeing how she gradually slackened in the needlework, which at the beginning seemed to occupy her totally: how it fell from her hand while she sat motionless over it, and at last, how the eyes which had appeared so studiously to avoid him throughout the day were turned and fixed on Crawford – fixed on him for minutes, fixed on him, in short, till the attraction drew Crawford’s upon her, and the book was closed, and the charm was broken. Then she was shrinking again into herself, and blushing and working as hard as ever; but it had been enough to give Edmund encouragement for his friend, and as he cordially thanked him, he hoped to be expressing Fanny’s secret feelings too.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 34 (London: Penguin, 1966)

It is no surprise that such an interesting, thought-provoking entry should come from Juliet McMaster, who I have had the great pleasure of knowing as a teacher. (Here’s the link to her guest post.) Also not surprising, given Jane Austen’s Shakespeare-like ability to write a text that operates on so many levels, is the realization that all the entries in the conversation about this post (see the comments section here), however apparently contradictory, are I think, equally true.

What I would wish to add to this conversation is the question (lifted from Tina Turner), “What’s love got to do with it?” In other words, I believe that what Edmund ultimately feels for Mary Crawford (and what the young female characters in the novel generally feel for Henry) isn’t love, it’s lust. It is, as we know, very common for Austen to place in her novels characters with extraordinary sexual magnetism: think of Wickham and Willoughby. Even in her juvenilia, in Jack and Alice, Austen describes Charles Adams as “so dazzling a beauty that none but eagles could look him in the face.” The interesting thing about Mansfield Park, is that while Austen often places male figures of extreme physical attractiveness in her works, in this novel the snake in the garden, who exercises the common Austen-novel function of tempting others to lust (not love), is both male and female: Mary and Henry.

Thanks to Homer, we generally associate the destructive (and implicitly sexual) call of the siren with women, owing to the female sirens in The Odyssey whose song lures sailors onto the rocks, where their ships are destroyed. It is nevertheless the case that in Greek tradition – as I believe Austen was well aware – sirens were both male and female, just as they are in this novel. In the Greece-obsessed Regency world Austen lived in (think of the female hair and clothing designed to look like Greek statues), there would have been many occasions to view actual Greek vases, and as classicists explain (see Jessika Akmenkalns, “Sirens,” review of “Wining, Dining, and Dying in Ancient Greece,” CU Art Museum, University of Colorado), many of these vases pictured male sirens. (You can find a good picture of a male siren in the collections of the J. Paul Getty Museum.)

We get a strong hint that this is exactly what Austen had in mind though her depiction of Henry Crawford reading Shakespeare, during which he pulls Fanny in completely (siren-like) through the seductive sound of his voice, which draws Fanny’s attention until her eyes are completely “fixed” on him and she cannot drop them away until he stops reading, and the “charm was broken.”

The siren-like sexual pull exerted by both Mary and Henry is why I believe all the comments made in response to “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?” make sense. Whereas, especially in a novel written in a Regency world, we can actually appreciate a woman who permits herself to experience sexual attraction without love as, for example, in the case of Elizabeth and Wickham – because isn’t this, in a way, something we can embrace as a kind of proto-feminism? – we cannot appreciate in the same way (or, on some levels, even respect) a male character who allows himself to be so seduced. I think the comments about our difficulties in embracing Edmund as a hero relate both to his poor judgment (as noted here) and to the fact that there is nothing progressive, only disappointing – and, let’s face it, historically rather common – about a male figure who falls into lust.

Dr. McMaster’s defenses of Edmund too, though, also make sense: especially the theory that this novel keeps presenting us with evidence that, at some level, in his heart, he always knows he is in love with Fanny, even as he is lured by the siren sound of Mary. His various cares of Fanny are the novel’s way of showing us that siren sounds, while powerfully seductive, are always being countered by that still small voice that tries (in spite of all) to protect us from ourselves – the moral love in the universe that will always attempt – if only we will listen! – to keep us away from the rocks.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sara Malton, Margaret C. Sullivan, Amy Patterson, and Theresa Kenney.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

November 19, 2014

The Real Reads Mansfield Park – a review

My friend Rose is thirteen and she loves to read, so I asked for her opinion of the Real Reads adaptation of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. I’ve written about the Real Reads adaptations of Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, but this time around I wanted to hear from someone in the target audience for these abridged versions of Austen’s novels – someone who hasn’t yet read Mansfield Park itself. The Real Reads Austen books are retold by Gill Tavner and illustrated by Ann Kronheimer.

I’m very happy to share Rose’s guest post with you, as part of the ongoing celebrations of 200 years of Mansfield Park. Rose lives in Massachusetts, and her favourite books include Harry Potter, by J.K. Rowling, Percy Jackson and the Olympians, by Rick Riordan, The Mortal Instruments series, by Cassandra Clare, Will Grayson, Will Grayson, by John Green, and Cornelia and the Audacious Escapades of the Somerset Sisters, by Lesley M. Blume. This last one, she says, is “the sweetest, saddest, happiest, book I will ever read in my entire life,” and she tells me her favourite word from that book is “defenestrate.” I hope you enjoy reading her review.

Can I first say that it has got to be tough to fit such a giant book into this tiny, cute, little illustrated thing. I read Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and it was big and complicated, mainly because the characters were too. This adaptation was really interesting to read and I haven’t read the full Mansfield Park so I knew nothing about what was supposed to or not supposed to happen. Just after I finished reading I was disappointed. The characters were a little boring and Fanny just annoyed me.

I thought it over more and realized that of course the characters are flat; this thing was a little over 50 pages. Fanny wasn’t annoying, she was human. A lot of characters I see are brave and strong and smart, their only flaw being their pride and overconfidence. It is rare and kind of neat to see someone uncomfortable and weak who does turn out to be the hero of the story.

Something else I was uncomfortable with was how unclear it was whether or not Edmund loves Fanny back. The point of view we saw made it seem one-sided. The short amount of space we had to let this happen made it seem like he wasn’t over Mary but he “needed” a wife. This made me feel almost like Fanny was being taken advantage of because she was so adoring. I was and still am curious to see what really happened.

These ideas, although simplified, need more explanation and depth for me to get them. This adaptation made me want to read the original book and hopefully will do the same for other young people. I honestly can’t wait until I see the characters as they really are and watch them grow. I am glad I read this to help me understand and grab my interest but it isn’t all that great on its own. My conclusion: read Mansfield Park in its entirety.

Read more about introducing Austen’s novels to younger readers on my page “Jane Austen for Kids.”

November 14, 2014

Fanny Price as a Student of Shakespeare

Twenty-eighth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

John Baxter is Professor of English at Dalhousie University, where he teaches classes on Early Modern literature, Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, rhetoric, and religion and literature. He’s the author of Shakespeare’s Poetic Styles: Verse Into Drama (Routledge) and many essays on Shakespeare, as well as on several other writers, including Ben Jonson, J.V. Cunningham, Janet Lewis, Yvor Winters, Helen Pinkerton, and George Elliott Clarke. With Gordon Harvey, he edited a collection of essays by C.Q. Drummond called In Defense of Adam: Essays on Bunyan, Milton, and Others (Brynmill Press/Edgeways Books), and with J. Patrick Atherton, he edited George Whalley’s groundbreaking translation of Aristotle’s Poetics (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

John Baxter is Professor of English at Dalhousie University, where he teaches classes on Early Modern literature, Elizabethan and Jacobean drama, rhetoric, and religion and literature. He’s the author of Shakespeare’s Poetic Styles: Verse Into Drama (Routledge) and many essays on Shakespeare, as well as on several other writers, including Ben Jonson, J.V. Cunningham, Janet Lewis, Yvor Winters, Helen Pinkerton, and George Elliott Clarke. With Gordon Harvey, he edited a collection of essays by C.Q. Drummond called In Defense of Adam: Essays on Bunyan, Milton, and Others (Brynmill Press/Edgeways Books), and with J. Patrick Atherton, he edited George Whalley’s groundbreaking translation of Aristotle’s Poetics (McGill-Queen’s University Press).

He’s also my father, and I’m absolutely delighted to introduce his guest post on Fanny Price and Shakespeare for my “Invitation to Mansfield Park” series.

The oral reading of Shakespeare in Mansfield Park summons up a number of contrasts. Theatrical skills are seen in a positive light rather than the negative light of Lovers’ Vows. The disreputable Henry Crawford gives a command performance that is admired by the characters – and surely by the author too. And the ever-vigilant Fanny Price is caught off-guard. But what, exactly, captures her attention? And why is the play Henry VIII?

In spite of her best intentions, Fanny cannot resist the performance:

She could not abstract her mind for five minutes; she was forced to listen; his reading was capital, and her pleasure in good reading extreme. To good reading, however, she had been long used; her uncle read well – her cousins all – Edmund very well; but in Mr. Crawford’s reading there was a variety of excellence beyond what she had ever met with. The King, the Queen, Buckingham, Wolsey, Cromwell, all were given in turn; for with the happiest knack, the happiest power of jumping and guessing, he could always light, at will, on the best scene, or the best speeches of each; and whether it were dignity or pride, or tenderness or remorse, or whatever were to be expressed, he could do it with equal beauty. – It was truly dramatic. – His acting had first taught Fanny what pleasure a play might give, and his reading brought all his acting before her again; nay, perhaps with greater enjoyment, for it came unexpectedly, and with no such drawback as she had been used to suffer in seeing him on the stage with Miss Bertram.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 34 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005)

Edmund notices that she is enraptured, that her eyes are “fixed on Crawford, fixed on him for minutes, fixed on him in short till the attraction drew Crawford’s upon her,” and with a jealously acute memory (which is perhaps more than fraternal), he later recalls this moment and imagines it as proof of an erotic attachment: “who that heard him read, and saw you listen to Shakespeare the other night, will think you unfitted as companions?”

That the reading of Shakespeare in this context is erotic there is little doubt, even if it is not quite as Edmund imagines it. But if Fanny’s enjoyment of Henry’s acting is rather different from Maria Bertram’s enjoyment, what does it consist of? And who knew that Henry’s acting in Lovers’ Vows “had first taught Fanny what pleasure a play might give”? The rehearsal scenes for that play seemed to have occasioned mostly pain for Fanny, so that “pleasure” here comes as a surprise, and “first taught” implies that reading Shakespeare offers a second lesson similar to the first. How could the pleasures of Lovers’ Vows conceivably be aligned with the pleasures of Henry VIII?

The Cambridge editor John Wiltshire remarks that Henry VIII was in vogue during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, particularly with Sarah Siddons in the role of Queen Katherine, and he notes as well that “the play’s many ‘fine speeches’ by male characters, together with the absence of bawdy passages, probably also contributed to its popularity and its choice by JA for Fanny’s reading aloud.” One of the virtues of this note is in drawing attention to the fact that it is Fanny who first selects Henry VIII for reading aloud (to Lady Bertram), even if Henry Crawford takes over the performing of it, but the emphasis on the negative principle of an absence of bawdy language and the miscellaneous feel of many fine speeches tends to suggest a principle of selection (on the part of both author and character) that is rather more adventitious than artistically or psychologically purposeful.

The Cambridge editor John Wiltshire remarks that Henry VIII was in vogue during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, particularly with Sarah Siddons in the role of Queen Katherine, and he notes as well that “the play’s many ‘fine speeches’ by male characters, together with the absence of bawdy passages, probably also contributed to its popularity and its choice by JA for Fanny’s reading aloud.” One of the virtues of this note is in drawing attention to the fact that it is Fanny who first selects Henry VIII for reading aloud (to Lady Bertram), even if Henry Crawford takes over the performing of it, but the emphasis on the negative principle of an absence of bawdy language and the miscellaneous feel of many fine speeches tends to suggest a principle of selection (on the part of both author and character) that is rather more adventitious than artistically or psychologically purposeful.

Jane Austen herself also conspires to make the choice of play seem serendipitous when she has Henry exclaim, “I do not think I have had a volume of Shakespeare in my hand before, since I was fifteen. – I once saw Henry the 8th acted. – or I have heard of it from somebody who did – I am not certain which. But Shakespeare one gets acquainted with without knowing how. It is part of an Englishman’s constitution.” Perhaps Austen, too, once saw Henry VIII acted or heard of it from somebody who did, though she is much less likely than Crawford to be uncertain which. In any case, it is worth considering more closely the versions she is likely to have known and the central role of Sarah Siddons that Wiltshire highlights.

A modern Shakespeare editor, Jay L. Halio, explains that “John Philip Kemble revived the play in 1788 after a twenty-year lapse, casting his sister, Sarah Siddons, in the role [of Queen Katherine] on Dr. Johnson’s recommendation” and that she was responsible for “a revolution in the representation of King Henry VIII, restoring the balance among principal characters that earlier eighteenth-century productions had lost in their emphasis upon the male leads.” Another critic, Hugh Richmond, argues that she “required of her fellow actors a shift in performance style toward the less ‘macho’ mode of interpreting Henry” that remains influential to this day.

If this is the performance style that Jane Austen knew, it seems plausible to assume that she deliberately chose the play because of a fundamental kinship between its heroine and the heroine of Mansfield Park. Both are women who may seem passive or inert from an external point of view, but who in reality are passionately devoted to their own deepest instincts and loyalties and who thus challenge the perspectives of the males in their circle.

At a general level, too, the play recommends itself because of its relentless investigation into the uses and abuses of power. Like Henry VIII, Mansfield Park presents a world in which love is hemmed in by a daunting array of powerful forces. Henry Crawford begins his pursuit of Fanny as a demonstration of his prowess, and when he becomes genuinely attracted to her, his sister represents that not as love but as triumph, celebrating “the glory of fixing one who has been shot at by so many; of having it in one’s power to pay off the debts of one’s sex.”

Fanny, of course, is not so interested in paying off the debts of her sex, but she is interested in a woman’s having the power to make her own choices, whatever forces of paternal and fraternal persuasion are arrayed against her.

“I should have thought,” said Fanny, after a pause of recollection and exertion, “that every woman must have felt the possibility of a man’s not being approved, not being loved by someone of her own sex, at least, let him be ever so generally agreeable. Let him have all the perfections in the world, I think it ought not to be set down as certain, that a man must be acceptable to every woman he may happen to like himself.” (Chapter 35)

Fanny and Katherine are admittedly faced with very different dilemmas, but they are alike in strongly resisting male pressure to alter their feelings in accordance with the putative advantages of a social or political order.

Yet Henry VIII, unlike Lovers’ Vows, does not provide the individual characters of Mansfield Park with quite the same chance to act out or project their own peculiar wishes and desires; what really counts in the oral reading of Shakespeare is the opportunity to see things steadily and to see them whole. In Lovers’ Vows, too, while the other characters are preoccupied with their isolated parts, the lesson Fanny draws comes from the perspective that the acting of that play gives into the structure of her whole little world.

Her second lesson, from Shakespeare, is similar, and the pleasure Fanny takes from Henry’s acting is the vision it gives of a complete world: “The King, the Queen, Buckingham, Wolsey, Cromwell, all were given in turn.” Conspicuously, “the Queen” is included in Fanny’s list of characters; Shakespeare’s enchanting voices are not restricted to males who deliver many fine speeches. In the revolutionary representation of Queen Katherine by Sarah Siddons that Jane Austen is likely to have known lies a model of a female passion or desire which is capable of restoring a balance and which is put to surprising and creative use in Mansfield Park. Edmund is right to intuit that listening to Shakespeare is an erotic experience, though he doesn’t yet see how it all fits together, and he fails to understand, at this point, that it is he and not the masterful actor who is the ultimate target of that eroticism. It is all truly dramatic.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Sharon Hamilton, Sara Malton, Margaret C. Sullivan, and Amy Patterson.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

November 10, 2014

Tell, by Frances Itani

The Halifax Giller Light Bash is happening tonight at the Atlantica Hotel at 8pm, and I’m delighted to be one of the six panelists who are defending the books shortlisted for the Scotiabank Giller Prize. I’ll be championing Frances Itani’s beautiful and powerful novel Tell, which is set in the small town of Deseronto, Ontario, not long after the end of the Great War.

After we each make the case for why our chosen books ought to win the Giller ($100,000), everyone at the Halifax event (and at similar Giller Light Bashes in Vancouver, Calgary, Regina, Winnipeg, and Toronto) will watch the live announcement of this year’s winner. The event is a fundraiser for Frontier College, “Canada’s original literacy organization.” If you happen to be in Halifax this evening, I hope you’ll join us! Tickets are $8 for students, $12 in advance, and $15 at the door. Come out, have fun, and support a good cause.

After I agreed to defend Tell, I decided to go back and read Itani’s 2003 novel Deafening, because there are many links between the two books. In Tell, she focuses on four characters who appeared in the earlier novel, but weren’t central to the story. Deafening (which won a Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and was shortlisted for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award) takes place in Deseronto before and during the war, and the central character is Grania O’Neill, a young deaf woman who falls in love with a man who can hear, and who loves to sing. Deafening was Itani’s debut novel, and it received tremendous – and well-deserved – accolades for its depiction of silence, noise, and the challenges of communicating in Grania’s world.

As a critic and book reviewer, I have to say that I found it a little odd to sign on to praise and defend a book I hadn’t read yet – but I’m happy to say that I can recommend both of these novels highly, and that it will be very easy to cheer for Frances Itani and Tell tonight.

One of the things I found most moving about both Deafening and Tell is the way Itani draws connections between the experience of those at the front and the experience of those left behind. In Deafening, she traces the path of a stretcher bearer serving in Europe while she also follows the fortunes of his relatives in Deseronto during the influenza pandemic of 1918. In Tell, Kenan, a soldier who’s returned home disfigured and psychologically unable to leave his house, links his wife’s unfulfilled desire for a child with his own experience of the landscapes of war. The word “barren” startles him. “We’re barren, the two of us,” he thinks. “He had seen barren. Charred landscapes where nothing would grow. Trees without leaves, branches without birds. Razed earth that supported no life. Villages without people. Oh, yes, he had seen barren. He had known it intimately.”

As Tell opens, the war is over, and yet, of course, it will never really be over for these characters who endured those years and who will spend the rest of their lives coming to terms with the consequences. Itani asks, what do we tell each other about our experiences, and what do we conceal, and what is the cost of both concealing and revealing?

Kenan was adopted when he was very young, and he has no idea who his birth parents were, because someone “had sent out a great hush, a devouring, silencing hush, a wave that had rolled over anyone who might have knowledge of [his] birth.” Sometimes truth is hidden with silence; sometimes it’s hidden with lies. “When you learn that someone is lying to you,” says one of the other characters in Tell, “you start to lose your bearings.”

I read Deafening first, and I was interested to see just how often the word “tell” appears in the earlier novel. “Tell,” Grania says to her sister Tress, demanding that her hearing sister pass on what their parents are saying about her own future. “There’s nothing to tell,” replies Tess, trying to conceal the painful truth that Grania will be sent away to a school for the deaf.

Later, Grania’s husband says, “Tell me, so I’ll know. About being deaf. Start with the worst thing.” She thinks for a while and responds, “Not having information that everyone else has. No – worse is when information is withheld – the smallest detail – by someone who thinks it isn’t important enough to pass on.” She asks him to reciprocate by telling her some crucial detail that she can’t know:

“You tell something, something I can’t know about you.”

Tell.

He laughed. “You’ll never know how I sing. Sometimes I wish you could hear me.”

The contrast between the experience of a deaf person and that of a hearing person is no longer central in Tell, because Grania is away from Deseronto for a time, but the focus on information withheld is still at the heart of the novel. Both Deafening and Tell raise important questions about the stories we tell each other, and the stories we never tell anyone.

If you’ve read, or plan to read, either of these books, I do hope you’ll tell me what you think.

November 7, 2014

Worn Out with Civility at Mansfield Park

Twenty-seventh in a series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Sarah Woodberry is a writer and editor who has contributed to various print and online publications, including Reuters, SKI Magazine, and More Intelligent Life. She tells me that it wasn’t until about the third time she read Mansfield Park that she really began to appreciate the novel’s complexity. When she’s not rereading Jane Austen’s novels, she enjoys reading essays about them and browsing Janeite blogs. She says she “credits the lively online community of Janeites as providing some comfort against the hard reality of the finite number of words written by Austen herself.” I agree, and I suspect many of you will, too. Today she’s contributing to that ongoing conversation with this post on the challenge of being civil in Mansfield Park. Sarah lives in Darien, Connecticut. You can find her blogging about reading and writing at WordHits, and you can also connect with her on Twitter @WordHits.

“I am worn out with civility,” said [Edmund]. “I have been talking incessantly all night, and with nothing to say. But with you, Fanny, there may be peace. You will not want to be talked to. Let us have the luxury of silence.” Fanny would hardly even speak her agreement. A weariness, arising probably, in great measure, from the same feelings which he had acknowledged in the morning, was peculiarly to be respected, and they went down their two dances together with such sober tranquillity as might satisfy any looker-on that Sir Thomas had been bringing up no wife for his younger son.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 28 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

One of the great pleasures of reading Jane Austen is that while you are lured along by her refined and carefully measured prose, suddenly off the page jumps one of her distinctive zingers: “I am worn out with civility,” says Edmund Bertram in Mansfield Park.

So often when reading Austen’s novels, I catch myself laughing out with surprise. Her vibrant, teasing social commentary still rings true after 200 years. Who hasn’t felt a touch of misanthropic fatigue after a long night of socializing and small talk?

Civility, or the lack of it, is a recurring theme in Austen’s works. She plays with it to challenge and define her characters, fine-tuning a Goldilocks scale of decorum. On one end, haughty and unfriendly behavior is the mark of villainous characters. Mrs. Norris, who torments Fanny in Mansfield Park, leads a cast of colorful Austen adversaries, which includes the Bingley sisters, Elizabeth Elliot, “Mrs. E,” and Fanny Dashwood—who is never to be confused with Fanny Price. Pre-transformation Darcy is a noted exception to this rule, as is perhaps the crotchety Mr. Palmer. At the other extreme, characters who are overly keen with their friendship and “happy manners” also turn out to be somewhat scheming and nefarious: Lucy Steele, Frank Churchill, Mr. William Elliot, the infamous George Wickham, and of course Mary and Henry Crawford in Mansfield Park.

Jane Austen’s heroines, however, exhibit just the right amount of “artless” civility, in that they are decorous and friendly with no ulterior motive other than to act properly. Although Marianne Dashwood and Emma Woodhouse each stumble with immaturity and a touch of thoughtlessness, none of Austen’s heroines is deliberately rude or unkind. Furthermore, they consistently—and rather impressively—resist the urge to retaliate when provoked by incivility. When Austen does allow one heroine to fire off a jab—Emma’s unfortunate ridiculing of Miss Bates—Emma regrets it fervently. This incident and its repercussions become a pivotal plot point. Certainly, Jane Austen did not approve of mean girls … or mean boys, ahem, Mr. Elton.

Although Austen does not allow her heroines to issue severe retorts, as narrator she often pokes fun at characters for them. Here in Mansfield Park, she is taking aim at Edmund. He complains, boasts almost, that he is “worn out with civility,” while at the same time he treats poor Fanny in a very off-handed manner. He’s so myopically distracted by Mary Crawford that he does not even notice how difficult this coming-out ball is for introverted Fanny, who also shrinks from “the toils of civility.” To boot, Fanny’s being stalked by the rakish Henry Crawford, and her heart aches because her dear brother William will be leaving in the morning, perhaps for years. Instead of concerning himself with Fanny’s troubles or comporting himself with the same manners he offers mere acquaintances, Edmund demands “silence” from her.

The first time I read this, all I could think was, “sad, unrequited Fanny.” Despite the lack of “tender gallantry” from Edmund, “her happiness sprung from being the friend with whom [he] could find repose.” I thought her as delusional as Caroline Bingley. In a moment of literary bewilderment, I was actually rooting for Henry Crawford. After all, he was so solicitous of Fanny when Edmund was not. But this being Austen, things are not what they seem. (You might think I would have learned from Wickham and Willoughby!)

“Conducted by Mr. Crawford to the top of the room.” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

What I mistook as Fanny’s desperation is actually a sign from Austen that these two are perfectly suited. Edmund’s distress arises from Mary Crawford’s cruel, and repeated, belittling of his chosen vocation as a clergyman. He’s drawn to Mary but conflicted by a growing realization that she is not for him. “It was not her gaiety that could do him good: it rather sank than raised his comfort.” One can only imagine that if Austen had paired them off, Edmund would likely have retreated to his library for good like Mr. Bennet. Unlike the social-climbing Crawford siblings, Edmund and Fanny both seek a quieter path.

Still, I’ve always found it interesting that Austen gives this “worn out with civility” line to Edmund, in a moment of benign insensitivity. It would’ve had more brio (à la Lady Catherine de Bourgh) had it been delivered by the cruel Mrs. Norris or the callous Bertram sisters. Perhaps this is Austen’s way of indicting Edmund for standing by and letting his family treat Fanny so abominably for so long? Indeed, Fanny endures years of demeaning treatment from the Bertrams, and as a result, she is generally slighted by all her acquaintance.

But what makes the incivility so grueling in Mansfield Park, compared to other Austen novels, is that Fanny has no support system. Lizzie Bennet can confide in Jane, and, at a particularly low moment, her Aunt and Uncle Gardiner whisk her off to tour the countryside. Likewise, the Dashwood sisters have each other and their caring mother. Anne Elliot, though dismissed by her father and sister, has Lady Russell, Mrs. Smith, and the good opinion of her neighbors. Finally, Emma has her entourage. But Fanny is alone—a sort of Cinderella step-child, who for solace retreats to the abandoned attic schoolroom with its unlit fireplace. Nevertheless, Fanny’s good and gracious nature prevents her from growing bitter towards the Bertrams, or anyone. Instead, Fanny serves as a paragon of forbearance and civility. As such, she proves herself far superior to her cousins Maria and Julia Bertram despite the deliberate effort made to raise Fanny as their subordinate—another delicious Austen irony. Ultimately, Fanny comes to love and to bring out the good in the Bertrams.

While all turns right and perfectly happy for her, and for Edmund who sees the light, going through all this with Fanny quite puts one through the wringer. Indeed, Mansfield Park is best read with a restorative cup of tea in hand. Each time I close the book I cannot help but say, on Fanny’s behalf, “I am worn out with civility!”

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by John Baxter, Sharon Hamilton, and Sara Malton.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 31, 2014

Fanny Price, Mind Reader

Twenty-sixth in a series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I’m very happy to introduce Joyce Tarpley’s post on Mansfield Park. Joyce teaches composition and literature full-time at Mountain View College in Dallas, Texas. She holds a Ph.D. in literature from the University of Dallas and has published a book on Mansfield Park titled Constancy and the Ethics of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park (Catholic University of America Press, 2010). These two essays also reflect her continuing interest in themes relating to males in Austen’s novels: “Sonship, Liberty, and Promise-Keeping in Sense and Sensibility,” published in Renascence: Essays in Values and Literature 63.2 (2011), and “Playing With Genesis: Sonship, Liberty, and Primogeniture in Sense and Sensibility,” published in Persuasions 33 (2011).

The fact that Jane Austen uses the word “mind” more times in Mansfield Park than in her other novels suggests a particular preoccupation with the way her characters think. (According to a search of the “Modern English Collection” on the University of Virginia Text Center website, the word “mind” appears 160 times in Mansfield Park compared to 135 in Emma, 104 in Sense and Sensibility, 69 in Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, and 64 in Pride and Prejudice.) Every Jane Austen novel features a kind of mind reading, or “people reading,” because she portrays each heroine, to different degrees, in the act of (1) discerning the “thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions,”* of other people and (2) discovering the same things about herself. The rhetorical situation for the heroine’s mind reading in a Jane Austen novel includes a subject, a purpose, and an audience. The subject is reality, or the truth, about herself, about someone else, and about the situation in which the two interact. The purpose is to choose, rightly, how to think and act in response to this subject. The audience is the heroine herself, or her consciousness, which is where the mind reading takes place.

Some commentators have a different name for this process. James Wood, for example, uses hermeneutics to describe this skill of the Austen heroine in his article titled “The Birth of Inwardness: The Heroic Consciousness of Jane Austen.” Citing theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, a contemporary of Austen’s who popularized hermeneutics for Bible study, Wood argues that “[s]omeone who understood other people, who attended to their secret meanings, who read people properly, might have been called hermeneutical” (The New Republic, August 17 & 24, 1998). It should come as no surprise that Fanny Price is the most hermeneutical of Austen’s heroines. She is the best mind reader because of her humility and persistence in attending to her own “thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions” in an attempt to know herself. This self-knowledge forms the foundation upon which she draws accurate conclusions about – or readings of – the minds of others.

Fanny’s mind reading represents a synthesis. She uses her constancy, or integrity – what might be called her Christian-ethical perspective – as a filter that allows her to make sense of the disparate and contradictory data received through her senses. Aided by an incredibly retentive and accurate memory, this continuous process of reflection allows Fanny to “read” people accurately and to choose rightly how to respond to them.

But Fanny is not the only adept mind reader in Mansfield Park. Austen gives us two more examples with the Crawford siblings, both of whom are skilled at guessing the thoughts and feelings of others. Unlike Fanny, however, they use their powers to manipulate people rather than to understand or to help them. For example, reading Rushworth’s mind during the excursion to Sotherton allows Fanny to assuage his jealousy; reading Julia’s mind during the theatricals allows her to warn Edmund about his sister – even though he does not listen. Reading Edmund’s mind about Mary distresses her, and she censures herself for the jealous feelings that cause this distress. Perhaps the best example of Fanny’s mind reading, or at least the most important one for her happiness, is exemplified in the passage wherein she tries to calculate the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of Henry and Mary Crawford regarding his sudden seeming interest in marrying her:

Fanny, meanwhile, speaking only when she could not help it, was very earnestly trying to understand what Mr. and Miss Crawford were at. There was every thing in the world against their being serious, but his words and manner. Every thing natural, probable, reasonable was against it; all their habits and ways of thinking, and all her own demerits. – How could she have excited serious attachment in a man, who had seen so many, and been admired by so many, and flirted with so many, infinitely her superiors – who seemed so little open to serious impressions, even where pains had been taken to please him – who thought so slightly, so carelessly, so unfeelingly on all such points – who was every thing to every body, and seemed to find no one essential to him? – And further, how could it be supposed that his sister, with all her high and worldly notions of matrimony, would be forwarding any thing of a serious nature in such a quarter? Nothing could be more unnatural in either. Fanny was ashamed of her own doubts. Every thing might be possible rather than a serious attachment or serious approbation of it toward her.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 31 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

Fanny seeks to “read” the information being presented to her, “the words and manner” of Mr. Crawford, by testing the source of that information – its reliability, its integrity, and its motive. Both Crawfords fail the reliability test based on Fanny’s memory of their past actions, including their trifling treatment of three Bertram siblings: Maria, Julia, and Edmund. Her knowledge of their character also causes her to doubt their integrity. Although she cannot fathom what their motive might be, her own humility makes it impossible for her to believe Mr. Crawford could have any serious interest in her. Such an interest is as “unnatural” to Fanny as it would have been to readers earlier in the novel. Fanny’s conclusion is categorical; despite Henry’s “words and manner” there is no doubt in her mind that neither a “serious attachment nor serious approbation of it” could be possible.

Subsequent events prove that Fanny knows Henry better than he knows himself. Despite a temporary softening toward him, brought on by living in the depressing Portsmouth home of her parents, and despite wishful thinking on the part of many readers – and even the narrator* – Fanny’s initial reading of Henry is correct. His love for her, genuine though it may be, cannot change his character. Mary herself provides the best evidence that her brother is incapable of a long-term (let alone lifetime) marital commitment: “I know that a wife you loved would be the happiest of women and that even when you ceased to love she would yet find in you the liberality and good breeding of a gentleman.” Mary knows that Henry will eventually grow bored with Fanny, cease to love her, and trifle with other women as cavalierly – albeit discreetly and politely – as he commits adultery with Maria. Fanny’s mind reading allows her to discern the “secret meanings” of the Crawfords’ words and actions, meanings of which even they themselves are not fully aware. By contrast, the Crawfords’ lack of self-knowledge leads to their failure to read accurately the mind – thoughts, feelings, desires, and intentions – of Fanny Price.

Notes:

* This phrase comes from Lisa Zunshine’s article titled “Why Jane Austen Was Different, And Why We May Need Cognitive Science to See It” (Style 41.3 [2007] 275-98), in which she explains mind reading by reference to “theory of mind,” a concept that cognitive scientists and philosophers of mind use “interchangeably” with the term.

* For discussion and analysis of the narrator’s “tacit approval” of the Fanny/Henry marriage that might have been, see “Constancy: A Reading” in Constancy and the Ethics of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park, 50.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sarah Woodberry, John Baxter, and Sharon Hamilton.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 28, 2014

Tea with JASNA Nova Scotia

The next JASNA Nova Scotia meeting will be on Sunday, November 9th, at 2 p.m., when we’ll meet in Halifax for tea, a short business meeting, and conversations about the 2014 JASNA AGM in Montreal. Please let Anne, our Regional Coordinator, know if you’re interested, or tell me (either by email – semsley at gmail dot com – or by leaving a comment here) and we’ll give you details about the location.

I’ve been rereading The Jane Austen Cookbook, by Maggie Black and Deirdre Le Faye, and I’m trying to decide whether to make “Mrs. Perrot’s Heart or Pound Cake” (“If you chuse Currants ¾ of a pound well washd & pick’d to be strew’d over them just as they are put into your Tins”), “Martha’s Gingerbread ‘Cakes’” (which we’d call biscuits or cookies, made with black treacle, or molasses), or “Ratafia Cakes” (ground almonds, egg whites, sugar, and orange liqueur).

Vote for your favourite in the comments below – even if you won’t be in Halifax on November 9th – and I’ll (attempt to!) make whichever recipe wins the popular vote.

October 24, 2014

On Turning Down Marriage Proposals

Twenty-seventh in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Syrie James, hailed as “the queen of nineteenth century re-imaginings” by Los Angeles Magazine, is the bestselling author of nine critically acclaimed novels, including Jane Austen’s First Love, The Missing Manuscript of Jane Austen, The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen, The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë, Dracula My Love, Nocturne, Forbidden, Songbird, and Propositions. Her books have been translated into eighteen languages, awarded the Audio Book Association Audie, designated as Editor’s Picks by Library Journal, named a Discover Great New Writers Selection by Barnes and Noble, a Great Group Read by the Women’s National Book Association, and Best Book of the Year by The Romance Reviews and Suspense Magazine.

Syrie James, hailed as “the queen of nineteenth century re-imaginings” by Los Angeles Magazine, is the bestselling author of nine critically acclaimed novels, including Jane Austen’s First Love, The Missing Manuscript of Jane Austen, The Lost Memoirs of Jane Austen, The Secret Diaries of Charlotte Brontë, Dracula My Love, Nocturne, Forbidden, Songbird, and Propositions. Her books have been translated into eighteen languages, awarded the Audio Book Association Audie, designated as Editor’s Picks by Library Journal, named a Discover Great New Writers Selection by Barnes and Noble, a Great Group Read by the Women’s National Book Association, and Best Book of the Year by The Romance Reviews and Suspense Magazine.

Syrie’s article “Jane’s First Love?” about Edward Taylor, a young man upon whom Jane Austen admittedly “fondly doated,” appeared in the July/August 2014 issue of Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine. With Diana Birchall (whose guest post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” was called “The Scene-Painter”) Syrie co-wrote “The Austen Assizes” for the JASNA AGM in New York in 2012 and “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park” for the Montreal AGM last month. Syrie is a life member of the WGA and JASNA and lives in Los Angeles. You can find her on Facebook, Twitter, and at syriejames.com.

On their way to Montreal, Syrie and her husband took a cruise from Boston to Quebec City, and when they stopped in Halifax, I got to have the pleasure of showing them around the city on a glorious fall day. We started at the Public Gardens, where the dahlia garden was a highlight, and then toured the Citadel, from which we enjoyed the fantastic views of the city and the harbour. A couple of weeks later, we explored the Montreal Botanical Garden together on an equally beautiful fall day. Syrie and I share a fascination with the strength of character Fanny Price demonstrates when she resists the attempts of all her relatives and friends to persuade her to marry Henry Crawford.

Montreal Botanical Garden

“Am I to understand,” said Sir Thomas, after a few moments’ silence, “that you mean to refuse Mr. Crawford?”

“Refuse him?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Refuse Mr. Crawford! Upon what plea? For what reason?”

“I – I cannot like him, sir, well enough to marry him.”

“This is very strange!” said Sir Thomas, in a voice of calm displeasure. “There is something in this which my comprehension does not reach. Here is a young man wishing to pay his addresses to you, with everything to recommend him: not merely situation in life, fortune, and character, but with more than common agreeableness, with address and conversation pleasing to everybody. And he is not an acquaintance of to-day; you have now known him some time. His sister, moreover, is your intimate friend, and he has been doing that for your brother, which I should suppose would have been almost sufficient recommendation to you, had there been no other. It is very uncertain when my interest might have got William on. He has done it already.”

“Yes,” said Fanny, in a faint voice, and looking down with fresh shame; and she did feel almost ashamed of herself, after such a picture as her uncle had drawn, for not liking Mr. Crawford.

“You must have been aware,” continued Sir Thomas presently, “you must have been some time aware of a particularity in Mr. Crawford’s manners to you. This cannot have taken you by surprise. You must have observed his attentions; and though you always received them very properly (I have no accusation to make on that head), I never perceived them to be unpleasant to you. I am half inclined to think, Fanny, that you do not quite know your own feelings.”

“Oh yes, sir! indeed I do. His attentions were always – what I did not like.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 32 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1892)

From the Little, Brown and Company edition of Mansfield Park, 1892.

I admire Fanny Price, and nowhere more than in this scene, where – although greatly distressed – she refuses to marry Henry Crawford, despite the angry disapproval of her uncle.

The hallmark of every Jane Austen novel is the contrast between superficial appearances and true character – the ultimate lessons being that first impressions can be misleading, surface qualities are not real, and a person’s deeds, not their words, are the true window to their moral character.

This theme is prevalent in every page of Mansfield Park, where everyone except Fanny seems to be blinded by appearances. Even we, the reader, are blinded on a first perusal of the novel. Fanny appears to be frustratingly mousy and timid, while Mary and Henry Crawford at first glance are far more charming and interesting. But when all is said and done, we realize that Fanny is not mousy at all.

Illustration by Hugh Thomson.

I love Fanny because she stands up for what she believes in and won’t let anyone persuade her to do otherwise. Most young ladies in her position, I think, would have accepted Henry Crawford in a heartbeat. Fanny is a poor relation, with apparently few if any marital prospects. Henry is handsome, rich, and charming, and he showers her with attention. Everyone at Mansfield Park wants Fanny to marry Henry – Sir Thomas is adamant, Mary expects it, and even Edmund thinks it’s a good idea – and I bet most readers are at first rooting for that connection. (I know I did on my first reading!) Jane’s sister Cassandra apparently campaigned to have Fanny marry Henry, a suggestion Jane thankfully did not follow.

But Fanny, unlike everyone else, is perceptive enough to see the real man beneath the charade. “I am so perfectly convinced that I could never make him happy, and that I should be miserable myself,” a weeping Fanny tells Sir Thomas. She, alone, knows Henry to be a callous flirt who finds “no one essential to him” and whose habits are such “that he could do nothing without a mixture of evil.” Henry calculatingly preys on Fanny’s feelings by arranging for her brother William’s promotion, immediately following this news with a marriage proposal. Fanny sees Henry’s romantic overtures “all as nonsense, as mere trifling and gallantry, which meant only to deceive for the hour” – and with good reason. When Henry’s personal challenge to win Fanny fails, he succumbs to his darker nature and runs off with Mrs. Rushworth.

Fanny refuses Henry Crawford’s proposal because she doesn’t love or respect him, and knows he cannot love her in return. No doubt, Jane Austen was drawing on her own personal experience when writing this sequence. As every Janeite knows, Jane famously accepted her one known marriage proposal from Harris Bigg-Wither, a wealthy, stuttering young man five years her junior who she’d known since childhood, only to recant the next morning.

There were many reasons why Jane might have felt compelled to marry Harris. The Austens were very close with the Bigg-Withers; Alethea and Catherine Bigg, Harris’s sisters, were two of Jane’s dearest friends. At age twenty-seven, Jane was already considered a spinster – and as Sir Thomas says to Fanny, you are “throwing away from you such an opportunity of being settled in life, eligibly, honourably, nobly settled, as will, probably, never occur to you again.” Indeed, by marrying Harris, Jane would have become the future mistress of Manydown Park, a large Hampshire house and estate in the neighborhood she loved, and where she had grown up. Marrying Harris would have given financial security to Jane and her parents and Cassandra for the rest of their lives.

Manydown Park

But Jane didn’t love Harris – perhaps didn’t even like him very much. And as Jane wrote in her unfinished novel The Watsons, “To pursue a man merely for the sake of situation, is a sort of thing that shocks me; I cannot understand it. Poverty is a great evil; but to a woman of education and feeling it ought not, it cannot be the greatest. I would rather be teacher at a school (and I can think of nothing worse) than marry a man I did not like.”

Illustration by Hugh Thomson

Only imagine what Jane must have felt – the deep emotional struggle she must have endured during that long, sleepless night after Harris’s proposal, as she agonized over her decision – and the pain and mortification of announcing that she could not marry Harris after all. Did Jane’s mother and father sharply criticize her decision when she rushed back to Bath? Were they as unfeeling as Sir Thomas was to Fanny? We do not know.

One thing is certain: Jane didn’t listen to what anyone else wanted. She followed her own heart and conscience, and demonstrated great inner strength and courage when she turned down Harris’s proposal, just as Fanny does when she refuses Henry Crawford. I admire them both for the choice they made. In this scene in Mansfield Park, Jane Austen is telling us something important: that she admires Fanny Price, because she possesses the moral conviction, good sense, and strength of character required of a true heroine.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Joyce Tarpley, Sarah Woodberry, and John Baxter.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 21, 2014

Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park

I was so excited when my copies of the new MLA (Modern Language Association) volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park arrived at my house yesterday. I’ve mentioned the book and my essay on “The Tragic Action of Mansfield Park” here before, and I did get to see it for the first time at the JASNA AGM in Montreal, but I now have my very own copies. The paperback cover features a painting called “Fond Memories,” by Charles Haigh Wood, and the cloth edition is a very pleasing dark purple. (That looks very much like Mary Crawford and Fanny Price to me – what do you think? Mary gazing at her own reflection in a pocket mirror, while Fanny sits with her hands clasped, looking up at Mary and figuring out what to make of her character.)

It was more than nine years ago that I first started to write about why Mansfield Park is a tragedy. I presented the first version of my essay at the 2006 JASNA AGM in Tucson, Arizona, after which it was published in Persuasions On-Line (you can still read that early version here). Later, I was delighted when it was accepted for publication in the volume of essays Marcia McClintock Folsom and John Wiltshire were editing for the MLA series. I had long been an admirer of Marcia’s previous books, Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Emma, and of John Wiltshire’s work on Austen, especially his books Jane Austen and the Body and Recreating Jane Austen and his Cambridge edition of Mansfield Park.

If you’re interested, you can read more about Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park and the topics covered by the editors and contributors on the MLA website.

And if you’d like to know more about my essay, you might be interested in this blog post I wrote earlier this year, on why “Mansfield Park is a Tragedy, Not a Comedy.”

I’m looking forward to reading the essays by Marcia and John and all the other contributors. I’m particularly intrigued by the titles of the essays by Pamela Bromberg – “Mansfield Park: Austen’s Most Teachable Novel” – and Peter Graham – “Ambiguities of the Crawfords.” Back when I taught classes on Jane Austen in the Writing Program at Harvard College, I enjoyed moving from the “light, and bright, and sparkling” world of Pride and Prejudice to the sometimes shocking world of Lady Susan and then, at the end of the semester, to the dark and complicated world of Mansfield Park.

I’m already persuaded that this one is the most “teachable” of the novels, and I’m keen to learn new approaches to understanding Mansfield Park, even though I’m not currently teaching in an academic institution. As Jennifer Weinbrecht of Jane Austen Books mentioned on Facebook when I posted the news about the book last night, “One doesn’t need to be a teacher to enjoy reading these books,” because “It’s always fun to gain new insights and discover new ways to think about our favorite works.” Well said, Jennifer!

October 18, 2014

The Custom of the Country Turns 101 Today

Today is the 101st anniversary of the publication of Edith Wharton’s novel The Custom of the Country. She called it her “Big Novel,” and her biographer Hermione Lee calls it her “greatest book.”

First edition of The Custom of the Country

Last year, to celebrate the 100th anniversary, I wrote a series of ten blog posts about the novel, its unforgettable (anti-)heroine Undine Spragg, and the changes Wharton made to the text between the version that was serialized in Scribner’s Magazine and the publication of the first edition on October 18, 1913.

On my page “The Custom of the Country at 100,” you can find links to all the posts in my series, plus links to several other essays on The Custom of the Country published elsewhere on the web – including one by Margaret Drabble, who calls the novel “one of the most enjoyable great novels ever written.” (And of course you can find out more about the edition of the novel that I prepared for the Broadview Literary Texts series.)

My Broadview edition of The Custom of the Country

I wrote, for example, about how my interest in local history, and a trip to the Halifax Citadel, led to my discovery of this fantastic novel. I talked about the source of , and traced connections from Undine to Lorelei Lee, Marilyn Monroe, and Madonna (“diamonds are a girl’s best friend”). I also explored Wharton’s influence on Candace Bushnell and Julian Fellowes. And there are several more posts – I hope you enjoy reading (or rereading) them.

Undine’s restless ambition is endlessly fascinating. I’ve always thought the best line in the novel is this one: “There was something still better beyond, then – more luxurious, more exciting, more worthy of her!” She’s never, ever satisfied, no matter how much money or power she has.

It was great to hear the news last week that Scarlett Johansson will star as Undine in a new television adaptation of the novel. I do think being a movie star might well be “the one part [Undine] was really made for” (to quote a line from the novel out of context).

I had such a great time putting together this celebration of The Custom of the Country last year that I decided to do something similar to celebrate the 200th anniversary of Mansfield Park – and we all know how that turned out! Instead of writing ten posts myself, I’m hosting a huge party for Mansfield Park, and now there are more than forty contributors writing guest posts. (Here’s your “Invitation to Mansfield Park,” for anyone who hasn’t received it yet.) I think Undine Spragg would be quite jealous that Fanny Price’s party is bigger than hers was. But then, Undine was celebrating only 100 years last year, not 200.

Happy 101st birthday to Undine Spragg and The Custom of the Country!