Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 29

December 20, 2014

“I purposely abstain”: When Vagueness Becomes Refusal

Thirty-eighth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Ryder Kessler is a Ph.D. student in English Literature at Columbia University, where he focuses on British and American novels of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, with particular attention to George Eliot, George Gissing, and Edith Wharton. He tells me his graduate work – including a master’s thesis on The House of Mirth – “explores the interplay between character choice and chance events in the plots of realist and naturalist fiction.”

I met Ryder ten years ago, when he was a freshman at Harvard University and he took the writing class I taught called “Jane Austen and Civil Society.” He tells me his “scholarly love affair with Jane Austen, and discomfort with the ending of Mansfield Park,” began in that class. He graduated summa cum laude from Harvard, with a secondary field in English.

Ryder is currently on leave from Columbia as CEO of the tech startup DipJar, which makes tip jars and donation boxes for credit cards. DipJar, he says, “is interested in solving problems that have arisen as we’ve shifted from carrying cash to plastic: employees lose out on the tips that help supplement their hourly wage and charities miss out on donations. That’s where DipJar comes in, offering customers one-step collection and seamless disbursement of credit card gratuities.”

It was a pleasure to discuss Mansfield Park with Ryder a decade ago, and it’s a pleasure to introduce his post on the ending of the novel today.

I purposely abstain from dates on this occasion, that every one may be at liberty to fix their own, aware that the cure of unconquerable passions, and the transfer of unchanging attachments, must vary much as to time in different people. I only entreat everybody to believe that exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier, Edmund did cease to care about Miss Crawford, and became as anxious to marry Fanny as Fanny herself could desire.

— From Mansfield Park, Chapter 48 (Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2001)

What does Fanny Price look like? Do we know, and does it matter? In my mind she’s always been blonde, as petite as she is shy, awkward as Alice (if Alice had been raised in a convent and dressed by the mother superior) shrinking before a rather Mrs. Norris-like Queen of Hearts. But, as far as I remember, Austen doesn’t tell us exactly what to see.

Perhaps our mental pictures are more fleshed out in the earlier novels. Do you remember when Mr. Darcy first appears in Pride & Prejudice? Of course: the gilded ballroom doors fly open, and here he comes — one of a dapper and haughty entourage, his dark eyes, dark hair, and square jaw setting him apart from the crowd.

Mr. Bingley was good looking and gentlemanlike; he had a pleasant countenance, and easy, unaffected manners. His sisters were fine women, with an air of decided fashion. His brother-in-law, Mr. Hurst, merely looked the gentleman; but his friend Mr. Darcy soon drew the attention of the room by his fine, tall person, handsome features, noble mien, and the report, which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year. The gentlemen pronounced him to be a fine figure of a man, the ladies declared he was much handsomer than Mr. Bingley….

— From Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 3 (New York: Longman, 2003)

Wait — maybe the picture isn’t so crystalline after all: Austen’s adjectives can be described as nothing other than vague. Bingley and Darcy are “good looking,” “gentlemanlike,” “pleasant,” “easy,” “unaffected,” “fine,” “tall,” “handsome,” “noble,” “fine,” and one is “handsomer” than the other. Tall is perhaps the only objective descriptor (applied earlier to Lydia and later to Miss Darcy), but height is relative; tall, too, is in the beholder’s eye. (I’d also argue that these scant instances of more objective description are those that work least. I never remember Lydia as taller than her sisters — her smallness of character suggests a smallness of person, while Jane stands out in the mind’s eye as tall and swanlike. But whether anyone else shares my mental images is unimportant: what matters is the richness of each reader’s minimally assisted mental picturing of the novel’s people and places.)

Reading Darcy’s entrance from a twenty-first-century vantage point, one might think of the first lesson now taught in creative composition classes: “Show, don’t tell” — and then of Austen’s stark but successful divergence from that now-cardinal rule. Don’t call a man handsome, an MFA professor might say, when you can identify his aquiline nose, square jaw, and penetrating ice-blue eyes. Don’t call a man a gentleman when you can bring into view the neatness of the part in his curly dark hair and the freshness of the white rose in his perfectly tailored jacket’s lapel.

Austen does not exactly “tell”: she shows, in vague strokes, the men “pronouncing” and the ladies “declaring” their unspecific impressions of the objects in their sight. Contrary to what we might assume, though, this vague description doesn’t preclude a detailed mental image from coming into view — in fact, it may even be the key to promoting the reader’s subjective painting of a personal image of the places and people brought into the text’s frame.

My experience of vividly picturing Mr. Darcy is echoed by Philip Hensher in a review of Claire Harman’s book Jane’s Fame:

What does Mr. Darcy look like? Anyone who has read Pride and Prejudice will be able to give an answer. I believe that he is tall, squarejawed, beetle-browed, slightly weather-beaten and dark-haired…. [O]n returning to the novel, we find a strange thing. The one feature in that list which I would have thought beyond dispute is that he has dark hair. … [But] Austen very rarely gives anything approaching a personal description of a character, and loses almost nothing by her decorous omission. Darcy might perfectly well be ginger; and yet not one reader in ten thousand by now believes him to be anything but black-haired (“Now universally acknowledged,” The Spectator, 4 April 2009).

We’re told very little, but we see very much. Hensher calls Darcy’s dark hair one of many “accretions” that the Austen canon has received over the two hundred years since the novels’ appearance, and he identifies Darcy’s dark hair as a shared — not a subjective — reality in readers’ experience of the text.

Indeed, one could claim that we have rich mental pictures of Pride and Prejudice only from seeing it so often on film. For me, though, this explanation cannot suffice: I’ve never watched the encyclopedic BBC adaptation with the shirtless Colin Firth, and I have only the faintest recollections of the liberally interpreted Keira Knightley film. Darcy’s dark hair (and his square jaw) are impressions that predate any exterior visual experience of the story, like my certainty of Jane Fairfax’s red hair and green eyes, and of the resemblance between Fanny Price and a more austere and retiring version of Alice — or, perhaps more accurately, of the little blonde girl in Velazquez’s Las Meninas.

In contemporary realism, a specific detail that rings true in the mind’s ear and eye — a detail that has what James Wood might call “thisness” — reifies the reality of the moment on the page and, metonymically, establishes the metaphysical grounded-ness of the person and scene it describes (How Fiction Works [New York: Picador, 2008]). “By thisness,” Wood says, “I mean any detail that draws abstraction toward itself and seems to kill that abstraction with a puff of palpability, any detail that centers our attention with its concretion.” He includes a long list of examples from authors from Pushkin to Beatrix Potter to Flaubert: “By thisness, I mean the moment when Emma Bovary fondles the satin slippers she danced in weeks before at the great ball at La Vaubyessard, ‘the soles of which were yellowed with the wax from the dance floor.’” But Austen eschews thisness for a descriptive vagueness that embraces the imaginative possibilities of ambiguity. (Wood says about Austen that she “gives us none of the visual furniture we find in Balzac or Joyce, and hardly ever stops to describe even a character’s face. Clothes, climates, interiors, all are elegantly compressed and thinned,” but he does not delve into how this “compression” and “thinning” also works.)

In Seven Types of Ambiguity (1930), William Empson elucidates “vagueness” by pointing us to texts that draw attention to unseen subtextual meanings by their lack of clear textual meanings. Quoting Max Beerbohm: “Zuleika was not strictly beautiful. Do not suppose that she was anything so commonplace; do not suppose that you can easily imagine what she was like, or that she was not, probably, the rather out-of-the-way type that you particularly admire.” This is an ambiguity of the sixth type, “when a statement says nothing, by tautology, by contradiction, or by irrelevant statements; so that the reader is forced to invent statements of his own….” The description tells us nothing except what is not there — we must fill in the content. Or, as Empson says: “it is not obvious what we are meant to believe at the end of it. But it cannot be said to represent a conflict in the author’s mind…” (New York: New Directions, 1966).

We see this type of ambiguity in Austen’s childhood novel Jack & Alice, in the description of Lady Williams: “Tho’ Benevolent & Candid, she was Generous & sincere; Tho’ Pious & Good, she was Religious & amiable, & Tho’ Elegant & Agreable, she was Polished & Entertaining.” These antitheses tell us little as they close off the space in which Lady Williams can exist — instead, they open up a deeper space in which we must go find her. The technique appears earlier in English prose. In John Lyly’s Euphues and his England, Philautus spots the perfect woman, described in a long list of antitheses, ending “And more easy it is in the description of so rare a personage to imagine what she had not, than to repeat all she had.” (Euphues and his England [1580] in S. L. Edwards, ed., An Anthology of English Prose [London: Cambridge University Press, 1953]). The space left open by vagueness requires readerly work to be filled in.

Shifting imaginative work onto the readerly plane not only serves to engage, but it also strengthens Jane Austen’s greatest writerly accomplishment: free indirect discourse. Our consciousness is joined with the characters’ as we are spurred to co-create the visual world through their eyes. By extension, then, our imagination models the interpretation we must do as readers — like the interpretative work the characters are doing in examining the world around them and themselves. Is Mr. Darcy essentially good? Is Henry Crawford reformed? Is Edmund worth waiting for? We, like Austen’s heroines, have limited information — the world is thick with moral vagueness — and we must fill in the picture from the little information we can get.

But what happens when Jane Austen’s narrator fails to provide basic descriptive information that has moral — and not just sensory — content?

I cannot think of an instance other than Austen’s “purposeful abstention” at the conclusion of Mansfield Park in which the strategy of vagueness is acknowledged in the text itself — in which the narrator invokes the power of vagueness as a mode for shifting imaginative and interpretative work from the text to the reader. Let us revisit it:

I purposely abstain from dates on this occasion, that every one may be at liberty to fix their own, aware that the cure of unconquerable passions, and the transfer of unchanging attachments, must vary much as to time in different people. I only entreat everybody to believe that exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier, Edmund did cease to care about Miss Crawford, and became as anxious to marry Fanny as Fanny herself could desire. (Chapter 48)

This is a clear repudiation of responsibility through the withholding of fact: the narrator does not give us event or speech and then leave it to us to mine moral meaning — such as when we see Fanny’s conversations with Mary Crawford, or letters from Henry, or chats between Fanny and her uncle or between Fanny and Edmund.

This is not vague description after all: it is a renunciation of fact altogether. Remember the ending of “The Sopranos” that so angered viewers — a sudden cut to black? Similarly, Mansfield Park leaves us not with information we must interpret, but with no information at all.

Why? Because fact, here, would undermine the union Austen has secured for her heroine. “[It] is not obvious what we are meant to believe at the end of it. But it cannot be said to represent a conflict in the author’s mind”: Austen, I think, is unconflicted about joining Edmund and Fanny at the novel’s close. But is this marriage mere weeks later? Months? Years? A short period might read as too little time for those who question the end of Edmund’s caprice; a long gap might be too much for those who question the certainty of his commitment.

And this doubt stands in for broader doubt about the morality of their union, shifted, as they have, from sibling-like cousins to lovers. The details cannot be named: if named, they would be fixed. And if fixed, they would force the reader from the ambiguity of the unnamed to confrontation with events that, like a weak-chinned Mr. Darcy, very well might fail to ring true.

In Austen’s other novels, marriage happens only after epiphany. Elizabeth and Emma realize that until this day they never knew themselves; then, with this new self-awareness and interpretative ability, they see the men they love. But Fanny does not change, and Edmund never leaves behind his changeability. This, I think, is why I’ve always felt that Mansfield Park ends in a rather minor key, without the convincing cadence of the other novels. And it is a difference exemplified by Austen’s uncharacteristic withholding of basic information — not vagueness, but refusal.

Fanny’s great triumph is her steadfast virtue, but its steadfastness crowds out room for growth. If Austen’s narrator did not abstain from providing the fact of when the main couple’s union takes place — mirroring, in her abstinence, the chastity of her main character — she would, in Wood’s words, “center our attention with its concretion.” And, for Mansfield Park, this concretion would be weight around the feet of an ending that the novel wishes would soar.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: the last post, on the last two paragraphs of the novel, by Sheila Johnson Kindred.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss the rest of the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 19, 2014

“A Matrimonial Fracas”

Thirty-seventh in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Sheryl Craig is an Austen scholar with a Ph.D. in nineteenth-century British literature from the University of Kansas. She’s a life member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and editor of JASNA News. Sheryl has published articles in Persuasions, Persuasions On-Line, The Explicator, and Jane Austen’s Regency World magazine, and on the websites of the Jane Austen Centre and Chawton House Library. In 2008, Sheryl was selected to be JASNA’s International Visitor, and in 2011-2012, she was JASNA’s Traveling Lecturer for the Central Region. She has presented at regional and national JASNA conferences and to the Scottish branch of the Jane Austen Society. I’m happy to share with you her post on Mansfield Park and divorce.

In 1812, Thomas Rowlandson produced three separate prints in a series titled “The Secret History of Crim Con.” The print above was the second in the series. The individual panels on the prints depict the absurdities of adultery cases. It was incredibly easy to divorce a woman for adultery; a stroll in the shubbery, a letter, a carriage ride, or the gossip of servants would hold up as evidence in court. (From the Lewis Walpole Digital Library at Yale; reproduced with permission.)

Mr. Rushworth had no difficulty in procuring a divorce; and so ended a marriage contracted under such circumstances as to make any better end the effect of good luck not to be reckoned on. She had despised him, and loved another; and he had been very much aware that it was so. The indignities of stupidity, and the disappointments of selfish passion, can excite little pity. His punishment followed his conduct, as did a deeper punishment the deeper guilt of his wife. He was released from the engagement to be mortified and unhappy, till some other pretty girl could attract him into matrimony again, and he might set forward on a second, and, it is to be hoped, more prosperous trial of the state: if duped, to be duped at least with good humour and good luck; while she must withdraw with infinitely stronger feelings to a retirement and reproach which could allow no second spring of hope or character.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 48 (www.mollands.net)

In the Western world in the twenty-first century, infidelity no longer shocks us, and adultery has ceased to be, as Edmund Bertram describes it in Mansfield Park, a “dreadful crime.” Today, if Maria Rushworth left her husband in order to take up residence with Henry Crawford, her family might be initially surprised, but not as devastated by the scandal as they are in Jane Austen’s novel. The modern Bertram clan would probably take Mary Crawford’s pragmatic advice to say nothing to the couple themselves and “let things take their course.” Divorce has lost its sting.

In Jane Austen’s day, divorce was not only considered immoral and illegal, it was financially devastating to the wife and costly to her alleged lover, and, although the woman’s lover could pay his debt to society and begin again, the stigma of immorality and criminality followed the woman for the rest of her life. The legal jargon for an adultery case was “criminal conversation,” usually abbreviated to crim.con, and while the wife had broken the law by her infidelity, the courts, and society in general, turned a blind eye to the adultery or adulteries of the husband in the case. Samuel Johnson expressed the prevailing view: “a husband’s infidelity is nothing” because he “imposes no bastards upon his wife.” A woman’s adultery was quite another thing, and a man who dared to dally with another man’s wife was generally fined between £5,000 and £10,000, to be paid to the husband he had distressed and embarrassed.

By the time Jane Austen published Mansfield Park in 1814, divorce had become a predictable process which began with a legal separation from bed and board in the Civil Courts and progressed, still as a legal separation, through the Ecclesiastical Courts of the Church of England. The final, third step was to petition Parliament with a divorce bill, which had to be passed by both houses of Parliament and signed by the King, just like any other law. Each divorce bill was individual and unique, written for the petitioner, who was the husband. Women could not petition Parliament, so a woman could not divorce her husband. She could only be divorced by him.

By the time Jane Austen was born, about one marriage in 3,000 ended up in court, and Parliament divorced, on average, two couples a year. The average divorce required two or three years to work its way through the legal system. Both Civil Courts and Ecclesiastical Courts sanctioned “separation from bed and board,” that is, a legal separation, but Civil Courts had no authority to terminate a marriage, and Ecclesiastical Courts refused to do so; therefore, separated spouses remained legally married.

In this 1813 print by Thomas Rowlandson (above), Princess Caroline resists the amorous advances of one of her husband’s cronies. Meanwhile, the Prince of Wales turns his back on his wife’s distress to collude with one of his many mistresses and the Lord Chief Justice about divorcing Princess Caroline for adultery. Despite his best efforts, the Prince was never able to procure any evidence or to produce two credible witnesses for his divorce bill. (From the Lewis Walpole Digital Library at Yale; reproduced with permission.)

At the Civil Courts, at the King’s Bench in London, a crim.con trial was actually a case between two men, the husband and the wife’s alleged lover, also known as the “gallant.” At least two witnesses had to be produced to testify to the wife’s adultery, although sexual intercourse did not have to be proven. The probability or possibility of adultery was sufficient, and the evidence was often extremely flimsy. Something as simple as a letter or an act of intimacy, like Julia Bertram’s observation of Henry Crawford holding her sister’s hand, would hold up in court as proof of adultery in a crim.con case. After hearing the judge’s summation, the jury generally decided a case in a few minutes by whispering among themselves in the jury box. Twenty minutes was considered a lengthy deliberation, and most adultery cases ended in the Civil Courts with separation from bed and board and the husband’s financial compensation.

The court usually granted the adulterous wife her “pin money,” the amount specified in her marriage settlement for the wife’s annual clothing allowance and pocket money. This was rarely more than £200 to £300 a year. By way of comparison, the Dashwood women in Sense and Sensibility feel impoverished with an annual income of £500.

The next step, if one chose to or could afford to take it, was further prosecution of the crim.con case in the Ecclesiastical Courts, the Doctors’ Commons. The Ecclesiastical Court tended to be the wife’s best chance of getting a sympathetic hearing, as it was the only time the husband’s adultery or cruelty were considered at all relevant. Ecclesiastical Courts took only written depositions from the husband, his wife, and the wife’s lover. The written deposition, however, at least gave the wife a chance to tell her side of the story. She could not even testify in her own defense in the Civil Court. The Ecclesiastical Court could overturn the rulings of the Civil Court to find in the wife’s favor, but they generally upheld the Civil Court’s ruling.

Petitioning Parliament for a divorce was expensive and embarrassing, but a divorce finally terminated the marriage and allowed the husband to gain full access to his wife’s dowry. While married or legally separated, the husband received only the interest from his wife’s dowry, but in a divorce predicated on the wife’s adultery, the wife in the case had violated her marriage contract and broken the law, which caused the dowry to default, in its entirety, to her husband. Maria Rushworth’s divorce case was financially a worst-case scenario for a woman; as Sir William Blackstone records in his Commentaries on the Laws of England, “in case of elopement, and living with an adulterer, the law allows [the wife] no alimony.”

Additionally, the divorced husband was now free to remarry. Technically, the remarriage of the wife was a matter for the husband, as the injured party, to decide. Denying the wife the option of remarriage was considered to be part of her punishment for committing the crime of adultery, and it was up to the husband to add a clause to his divorce bill giving his wife permission to marry again, if he chose to do so. The husband could also specify that his ex-wife could remarry but not any particular man or men named in the divorce bill. So Mr. Rushworth could grant Maria the right to remarry, but not to marry Henry Crawford, or his divorce bill could forbid Maria to remarry at all. The House of Lords would have upheld either stipulation, but the House of Commons would probably have argued the remarriage clause. Their position, which was the same as the Bishops of the Church of England, was that if the wife could not remarry, she was effectively condemned to a life of further immorality and prostitution. Legally, however, the husband was within his rights.

Most husbands added clauses which allowed their wives to remarry, but it was from purely selfish motives. If the divorced woman became another man’s wife, she also became his financial burden, so the ex-husband’s alimony payments ended with the ex-wife’s remarriage. James Rushworth, however, the richest character in an Austen novel, significantly richer even than Fitzwilliam Darcy, would not be at all motivated by financial incentives. Rushworth will be pocketing Maria’s dowry, every penny of it, and, because of her flagrant adultery, he will not be paying his ex-wife alimony anyway.

Mary Crawford predicts that “when once married [to her brother], and properly supported by her own family, people of respectability as they are, [Maria] may recover her footing in society to a certain degree. In some circles, we know, she would never be admitted.” A divorced woman could not be presented at court or publicly acknowledged by members of the royal family, so she was denied access to the most fashionable dinners, balls, and drawing rooms, but the rest of society also shunned her. Maria Rushworth would be no more welcome at a society hostess’s home than Admiral Crawford’s mistress. Some divorced aristocrats lived on the fringes of upper-class society, and, as Henry Crawford’s wife, Maria could, as Mary Crawford suggests, attempt to reestablish herself socially “with good dinners, and large parties.” However, most of the people Maria invited would either politely decline or bluntly refuse her hospitality.

Whether because of the remarriage clause in her divorce act or because of Henry Crawford’s indifference, the ex-Mrs. Rushworth is forced to accept the fact that she will never become Mrs. Henry Crawford. At the end of Mansfield Park, Maria Rushworth resigns herself to the fate of the vast majority of ex-wives in Regency England when she disappears into obscurity. Sir Thomas Bertram assumes the financial burden of providing for his daughter, although legally he has no obligation to do so.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Ryder Kessler and Sheila Johnson Kindred. This week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there’s one post per day.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 18, 2014

Flattery in Mansfield Park

Thirty-sixth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Elisabeth Lenckos is the co-editor, with Natasha Duquette, of Jane Austen and the Arts: Elegance, Propriety, and Harmony (Lehigh University Press, 2013), and, with Ellen J. Miller, of “All This Reading”: The Literary World of Barbara Pym (Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2003). At this year’s JASNA AGM in Montreal, she presented a paper on Mansfield Park, Elizabeth Inchbald’s plays, and the scandalous story and trial of Warren Hastings.

Elisabeth has taught comparative literature for more than twelve years and is currently writing a historical novel about an adventuress in Jane Austen’s world. Her story “Jane Austen: 1945” was published in Wooing Mr. Wickham (Honno, 2011) and her story “Mary Crawford’s Last Letter” was shortlisted for this year’s Chawton House Library Short Story Award.

Sir Thomas Bertram’s reflections on the effect of Mrs. Norris’s “excessive indulgence and flattery” prompted Elisabeth to explore the topic of flattery in Mansfield Park.

Sir Thomas Bertram’s reflections on the effect of Mrs. Norris’s “excessive indulgence and flattery” prompted Elisabeth to explore the topic of flattery in Mansfield Park.

Too late [Sir Thomas] became aware how unfavourable to the character of any young people, must be the totally opposite treatment which Maria and Julia had been always experiencing at home, where the excessive indulgence and flattery of their aunt had been continually contrasted with his own severity.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 48 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

The most memorable exchange Jane Austen wrote about the subject of flattery takes place in Pride and Prejudice when Mr. Collins unwittingly reveals that he prepares his clumsy obsequies by longhand:

“You judge very properly,” said Mr. Bennet, “and it is happy for you that you possess the talent of flattering with delicacy. May I ask whether these pleasing attentions proceed from the impulse of the moment, or are the result of previous study?”

“They arise chiefly from what is passing at the time, and though I sometimes amuse myself with suggesting and arranging such little elegant compliments as may be adapted to ordinary occasions, I always wish to give them as unstudied an air as possible.”

— From Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 14 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988)

The humor of the scene, arising from the consummate flatterer’s lack of awareness that he is being duped into giving away his secret by means of the praise Mr. Bennet lavishes on him, remains unequalled in the author’s oeuvre. Certainly, no situation as comical as this can be found in Mansfield Park which, in keeping with the novel’s more serious approach to human fallibility, treats flattery – defined by Johnson’s Dictionary as “fawning; false, venal praise” – with greater gravity.

“I am persuaded … my proposals will not fail of being acceptable.” Mr. Collins proposes to Elizabeth Bennet. Illustration by C.E. Brock. (http://www.mollands.net/etexts/images/pnpillus/pnpbrockwc11.jpg)

Flatterers abound at Mansfield Park, most notably, Mrs. Norris, Henry, and Mary Crawford. But their fawning fails to divert the reader, since it is a precarious, underhand activity, which inveigles its objects into an inflated, unrealistic sense of their supposed superiority. If, as in Mr. Collins’ case, the quality of flattery is to be judged by the subtlety with which it is performed, Mrs. Norris, of the Mansfield Park trio of sycophants, is the least accomplished, the venality of her praise so obvious, one wonders how the Bertrams can possibly be deceived. By contrast, the Crawfords’ adulations are far more elegant, with Mary taking the lead over her brother in terms of sensibility and diplomacy.

From the beginning, Mary considers including Fanny Price in her blandishments, and she inquires whether the young woman is “out,” in order to discover whether she is worthwhile complimenting (Chapter 5). Her question is therefore not so much evidence of Mary’s solicitude, but merely signifies the experienced flatterer’s attempt to establish the persons she should favor with her honeyed attentions – and those who will have to do without. There is no doubt that Mary is possessed of a natural tact, which prompts her to treat Fanny with an off-hand kindness; however, her growing interest in the Price girl is to be explained not by increasing fondness, but by the respect in which she perceives her to be held by Edmund, and later, Henry.

Henry’s flattery is altogether more distasteful, since he confuses the process of insinuating himself into the heart of a woman with love. Aimed at ladies who, when they lose their reputation, lose everything, Henry’s enticements have dangerous, ruinous consequences, as Maria Rushworth, née Bertram, discovers too late. Fanny Price intuits Henry’s lack of insight – to which he himself falls prey when he begins to believe his own fiction that his feelings for Fanny are profound – but it avails her little. Sir Thomas lashes out at her when she refuses Henry’s offer of marriage and exiles her to Portsmouth until she is willing to acknowledge the error of her ways.

Once there, Fanny indeed experiences a revelation. She realizes that civility, the lovely Cinderella to those ugly stepsisters, flattery and sycophancy, must be part of every household, because without consideration and mutual respect, there can be no happiness in the home. Her father’s lack of veneration for her mother and the inability of the Price family to maintain good manners wear on Fanny, and she longs to return to Mansfield Park. This does not mean she is a snob; she sees quality in her brother William and her sister Susan, and she does not blind herself to the rudeness of well-heeled people, such as Mrs. Norris and Maria Bertram. Unlike her aunt, whose “excessive indulgence and flattery,” has spoilt two of her nieces for the remainder of their lives, Fanny Price does not venerate rank for the sake of rank. As her name implies, she knows the true value of people and things.

Regardless of Fanny’s virtuous strength, however, Mansfield Park holds the stunning revelation that she is, nevertheless, susceptible to flattery. As the narrator tells us: “although there doubtless are such unconquerable young ladies of eighteen … as are never to be persuaded into love against their judgment by all that talent, manner, attention, and flattery can do, I have no inclination to believe Fanny one of them” (Chapter 24), and this information is crucial, since the “talent, manner, attention, and flattery” she mentions are those of Henry Crawford, who has just confided in Mary that he intends to employ these talents in order to make “a small hole” in Fanny’s heart. This phrase is possibly the most cruel, uncaring statement made by any young gentleman in Austen’s oeuvre, showing what is at stake if Fanny falls prey to his intrigues.

Austen’s novels feature many flatterers, who are also lovers, and pose a threat to the happiness of her heroines; Willoughby in Sense and Sensibility, Wickham in Pride and Prejudice, Frank Churchill in Emma, and Sir William Walter Elliot in Persuasion. Is Henry Crawford the most dangerous among them? The question is probably a matter for discussion, but he is the only Austen villain who has the added advantage of an equally devious sister, acting as his messenger and intermediary. Fanny Price is, among her leading ladies, alone in having to withstand the attack of not one, but two potential seducers – Henry and Mary who conspire to break down her reserve with the sibling weapon of their supposed charm, and, when their flattery fails to have an effect, resort to denunciation, and in Henry’s case, the punishment of the entire Bertram family.

It is only in the conclusion to the novel that we see just how charm-less the charismatic Crawfords are, and we breathe a sigh of relief that the spell they exerted on Edmund and his father was not meant to last. In the end, Fanny Price’s goodness and honesty prevail against the flattery of Henry, Mary, and Mrs. Norris, and once the three flatterers are exiled from Mansfield Park, truth and harmony rule her arcadia.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sheryl Craig, Ryder Kessler, and Sheila Johnson Kindred. This week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there’s one post per day.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 17, 2014

The Ghost of Another Novel Entirely

Thirty-fifth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Today’s guest post is by Lynn Shepherd, award-winning author of Murder at Mansfield Park and three subsequent literary mysteries, The Solitary House, A Fatal Likeness, and The Pierced Heart, inspired respectively by Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, the lives of the Shelleys, and Bram Stoker’s Gothic classic Dracula. All four of her novels have received Kirkus stars. You can visit her website and follow her on Twitter @Lynn_Shepherd.

Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can, impatient to restore everybody, not greatly in fault themselves, to tolerable comfort, and to have done with all the rest.

My Fanny, indeed, at this very time, I have the satisfaction of knowing, must have been happy in spite of everything. She must have been a happy creature in spite of all that she felt, or thought she felt, for the distress of those around her. She had sources of delight that must force their way. She was returned to Mansfield Park, she was useful, she was beloved; she was safe from Mr. Crawford; and when Sir Thomas came back she had every proof that could be given in his then melancholy state of spirits, of his perfect approbation and increased regard; and happy as all this must make her, she would still have been happy without any of it, for Edmund was no longer the dupe of Miss Crawford.

***

Henry Crawford, ruined by early independence and bad domestic example, indulged in the freaks of a cold-blooded vanity a little too long. Once it had, by an opening undesigned and unmerited, led him into the way of happiness. Could he have been satisfied with the conquest of one amiable woman’s affections, could he have found sufficient exultation in overcoming the reluctance, in working himself into the esteem and tenderness of Fanny Price, there would have been every probability of success and felicity for him. His affection had already done something. Her influence over him had already given him some influence over her. Would he have deserved more, there can be no doubt that more would have been obtained, especially when that marriage had taken place, which would have given him the assistance of her conscience in subduing her first inclination, and brought them very often together. Would he have persevered, and uprightly, Fanny must have been his reward, and a reward very voluntarily bestowed, within a reasonable period from Edmund’s marrying Mary.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 48 (www.mollands.net)

I first read Mansfield Park for my school leaving exams, so this is a novel that has been with me for the best part of 30 years. I’d read Pride and Prejudice before that, and I remember thinking, even then, that Mansfield Park was a very different animal. Pinning down exactly why it was so different was rather more puzzling. Mansfield Park does, after all, have the same “boy-meets-girl” love story at its heart, and the usual obstacles to the fulfilment of that love, whether social or self-imposed. So why do we find Mansfield Park so hard to like? As I have blogged elsewhere, the real problem with Mansfield Park is not its story, but its heroine. As Lionel Trilling famously opined, “Nobody, I believe, has ever found it possible to like the heroine of Mansfield Park.” And since even Austen’s mother found Miss Price “insipid,” this is not entirely down to a modern prejudice against heroines who sit on the sofa rather than get up and go. Nor is the hero much help – since Edmund has “formed her mind and gained her affections” she now, as Austen admits, “think[s] like him,” so we can hardly blame Fanny if she comes over as her cousin’s mini-me. But the result is rather a case of the bland leading the bland: as Kingsley Amis said (in one of my favourite quotes about the novel), “to invite Mr and Mrs Edmund Bertram round for the evening would not be lightly undertaken.”

So where am I going with this, and how does it relate to the two passages I have chosen?

The short answer is that I think Austen knows. Knows her aim to write a more serious novel has not quite come off, knows that her heroine is hard to like, and knows – most importantly – that she has wrenched the trajectory of her own plot to ensure Fanny gets her man.

You can see this, in the first of the two passages, in her reference to her heroine as “my Fanny.” No other heroine of hers is ever accorded the honour of the possessive pronoun, not even Elizabeth Bennet. And then, in the second passage, we have perhaps the most flagrant authorial mea culpa ever written. What’s fascinating about this paragraph is its adoption of the conditional tense: what would have happened. In other words, Edmund marrying Mary, and Fanny marrying Henry Crawford. Because that, after all, is the natural conclusion towards which the whole novel was tending. Despite Austen’s concerted campaign to weigh the scales against Mary Crawford, Edmund was most definitely in love with her, not Fanny, and even Austen admits that Henry Crawford had done enough to win over the punctilious Miss Price in the end. The momentum towards this ending is so strong, in fact, that only a juggernaut can stop it. And that’s what Austen is forced to supply. A deus ex machina plot device that is frankly unworthy of her: a completely implausible and (for Crawford) emotionally illogical elopement, which all takes place hugger-mugger out of view of the reader, because – I believe – even Jane Austen doesn’t think she can present those scenes to us and expect us to believe them.

And this is followed, shortly after, by the passage in which Jane Austen waves a magic wand and asks us to accept that the man who has only 20 pages ago referred to Fanny as his “only sister” has undergone a complete volte-face and fallen in love with her. “I only intreat every body to believe that [it was] exactly at the time when it was quite natural that it should be so, and not a week earlier.” Sorry, Jane, I love you dearly, but even I don’t buy that one.

These two passages are like the ghost of another novel, which was struggling to get out, and suffocated by its author for reasons of her own (and I have speculated about that, too). That ghost novel would have been much more like Pride & Prejudice – much more “light and sparkling,” and with another heroine entirely. That ghost first took shape when I was 18, and haunted me for years after. So much so, in fact, that I was eventually inspired to sit down and try to write that book myself. The result? Murder at Mansfield Park. And the rest, as they say, is history….

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Elisabeth Lenckos, Sheryl Craig, and Ryder Kessler. This week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there’s one post per day.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 16, 2014

“Never had Fanny more wanted a cordial”: Comic Relief and Word Choice in Mansfield Park

Thirty-fourth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Today is Jane Austen’s birthday! How are you celebrating? I celebrated on December 7th at a birthday lunch with JASNA Nova Scotia, and this past weekend, I visited the fabulous new Halifax Central Library to look for books by and about Jane Austen. To celebrate my own birthday back in September, I made a donation to the library’s “Share the Wow” fundraising campaign, so they sent me some bookplates and invited me to place them in books from their collection. (For $25, you, too, could put your name in one of their books.)

The library, which CNN named “One of 10 eye-popping new buildings that you’ll see in 2014,” opened on Saturday (read more about opening day here), and it’s a fantastic present for the city of Halifax.

I was lucky to see inside the Halifax Central Library a couple of months before it opened

Of course I went back to our new library on opening day

Today, I’m excited to be celebrating Austen’s birthday by sharing this guest post by Karen Doornebos with you. Karen and I invite you to raise a glass in honour of both Jane Austen and Fanny Price.

To Jane Austen!

Karen Doornebos is the author of Undressing Mr. Darcy, published by Penguin, Random House. Her first novel, Definitely Not Mr. Darcy, has been published in three countries and was granted a starred review by Publishers Weekly. Both books are very clever and very funny. I really like the moment in Definitely Not Mr. Darcy when the heroine realizes that “Regency life was grim for women, very grim, and this, too, had been one of Austen’s messages, just not the one Chloe had wanted to acknowledge.”

And there are several highly entertaining cameo appearances in Undressing Mr. Darcy, including one by Cornel West, who gives a lecture on Jane Austen and power at a JASNA AGM, just as he did at the 2012 JASNA AGM in New York. (You can listen to the lecture here. It was one of the best AGM talks I’ve ever heard – he says that “Philosophers tend to be obsessed with the theory of flames, but Jane Austen is the fire” – and I can see why Karen was inspired to include it in her novel.)

Karen lived and worked in London for a short time, but she tells me she’s now happy “just being a lifelong member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and living in the Chicagoland area with [her] husband, two teenagers, and various pets—including a bird.” “Speaking of birds,” she says, you can follow her on Twitter and Facebook . She hopes to see you there and on her website, www.karendoornebos.com .

Dear Fanny—

You know our present wretchedness. May God support you under your share! We have been here two days, but there is nothing to be done. They cannot be traced. You may not have heard of the last blow—Julia’s elopement; she is gone to Scotland with Yates. At any other time, this would have been felt dreadfully. Now it seems nothing; yet it is an heavy aggravation. My father is not overpowered. More cannot be hoped. He is still able to think and act; and I write, by his desire, to propose your returning home. He is anxious to get you there for my mother’s sake. I shall be at Portsmouth the morning after you receive this, and hope to find you ready to set off for Mansfield. My father wishes you to invite Susan to go with you, for a few months. Settle it as you like; say what is proper; I am sure you will feel such an instance of his kindness at such a moment! Do justice to his meaning, however I may confuse it. You may imagine something of my present state. There is no end of the evil let loose upon us. You will see me early, by the mail.

Yours, &c.

Never had Fanny more wanted a cordial. Never had she felt such a one as this letter contained. Tomorrow! To leave Portsmouth tomorrow! She was, she felt she was, in the greatest danger of being exquisitely happy, while so many were miserable. The evil which brought such good to her! She dreaded lest she should learn to be insensible of it. To be going so soon, sent for so kindly, sent for as a comfort, and with leave to take Susan, was altogether such a combination of blessings as set her heart in a glow, and for a time, seemed to distance every pain, and make her incapable of suitably sharing the distress even of those whose distress she thought of most.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 46 (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2012)

Comic relief. That’s why many of us, at least, laugh at the line: “Never had Fanny more wanted a cordial.”

As in all great comedy, timing is almost everything—delivery is the rest. Here the timing is impeccable and the delivery both deadpan and swift. But, more than merely slaking our thirst for comic relief after this especially torturous part of the novel (namely Fanny’s three months in Portsmouth), the line brings us relief and a medicinal in every sense of the word. More importantly, it offers us a glimpse into the power of Jane Austen’s word choice and how deftly she moves us from pathos to punchline.

The first, most obvious, and striking thing about the line is the incongruous image of Fanny, of all characters in Mansfield Park, holding a cordial. It seems out of character, though we are told early on Fanny does drink. She drinks diluted wine that (of course none other than) Edmund mixes for her (Chapter 7). So to visualize her with a drink doesn’t shock us, really. What jolts us is a direct statement putting the words “Fanny” and “want” in the same sentence and so near the end of the novel, when—up to this late hour—neither Fanny nor the narrator has referred to Fanny overtly wanting anything. And what does she want? A drink! A medicinal drink, perhaps—but still.

Up until this moment, Fanny has suppressed her wants and needs to such an extreme that in Portsmouth she has not articulated her desire to go back to Mansfield, and at Mansfield, she managed to survive without a fire in her room, without a true family or home to call her own and without any reciprocation from the man she has so deeply loved her entire life.

And this is what she wants? This is all she wants? A cordial? A restorative? As readers we have to laugh. Austen intended us to laugh here. It’s a perfect pay-off to pages and pages of dingy, dirty, and depressing detainment in Portsmouth. After three months of penance, Fanny and the reader get a real break—a cordial.

Interesting and worth noting too, is Austen’s choice of the word “cordial.” She did not, as she did in other novels, specify a drink such as the Constantia wine that Mrs. Jennings brings to Marianne after learning of Willoughby’s engagement. She did not use the (expensive) “French wine” she associated with Mr. Darcy, and neither did she choose the “Madeira and water” Emma suggests that Frank Churchill should drink at the Box Hill picnic.

Austen opted for “cordial,” a very deliberate choice.

This single word, with so many meanings to unpack, strikes, dare I say, a chord. Derived from the Latin and French, “cordial,” according to the Oxford English Dictionary, “appears in its origin a word of medicine.”

This makes so much sense, considering Fanny throughout the novel is known to be on the weak side, and in need of exercise to keep up some semblance of fortitude and health.

Equally appropriate is the French “coeur” at the—(forgive me) heart of—“cordial.” The first meaning listed in the OED for cordial is: “of or belonging to the heart.”

What a wonderful word to choose to describe this crucial and long-awaited letter from Fanny’s beloved Edmund, announcing her liberation from Portsmouth and his coming to rescue her from it.

The second listed meaning in the OED is: “of medicine, food, or beverage: stimulating, comforting, or invigorating the heart; restorative, reviving, cheering.” It goes on to mention “as in cordial water.” Indeed, Edmund’s letter does serve as a restorative—it restores Fanny back to her life at Mansfield. Ah, that sly Austen!

The third meaning of cordial: “Hearty: coming from the heart, sincere, genuine, warm, warm and hearty as a course of action or on behalf of a cause.”

Yet, beyond the myriad of nuances behind the word cordial, something else is at work in these few lines. What may also have been intentional on Austen’s part is that we (especially with our modern sensibilities), feel a twinge of excitement at the possibility of our heroine finally getting in touch with her desires, and perhaps growing and changing as we often want our heroines to do.

Fanny has expressed a desire! Could she possibly … become a strong-willed Elizabeth Bennet?

Austen quashes these hopes in the next sentence. Fanny, rather than following up on her wish for a cordial in the literal sense, and helping herself to Mr. Price’s no doubt potent and ample liquor cabinet to pour herself a stiff one (or even ringing for Rebecca to fetch her a medicinal), placates herself with the idea that the letter itself provides all the cordial she needs:

“Never had she felt such a one [cordial] as this letter contained.”

And, yes, yes it is a cordial in and of itself, but how about that drink, Fanny?

In true Fanny fashion, she denies herself her drink, and, worse, denies herself even a moment of happiness to celebrate that she is sprung from the Portsmouth prison. Once again, Austen gives us cause to smile, when in the very same sentence, she artfully pairs the words “danger” and “happy”:

“She was, she felt she was, in the greatest danger of being exquisitely happy, while so many were miserable.”

Catholic and Jewish guilt have nothing on Fanny Price! It would be dangerous indeed for her to be happy—especially “exquisitely” happy.

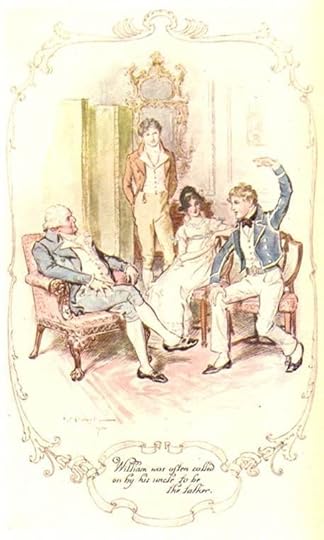

“There! – much good may such fine relations do you.” Illustration by C.E. Brock. (http://www.mollands.net/etexts/mansfieldpark/mpillus.html)

Austen follows this up with: “The evil which brought such good to her!” Yes, we admire Fanny for not popping champagne corks when her Mansfield Park “family” has suffered so much, but…. In this sixth sentence of the paragraph, Austen again chooses the word “evil,” and we have to laugh a little at Fanny’s overstatement of the problem, do we not? As if the plague or devil’s curse were upon them? “The evil” refers of course to the Crawfords (and Julia’s elopement), but when aligned with the “good” it brought Fanny, we detect Austen smirking somewhere behind Fanny’s hyperboles.

These subtleties are what make Mansfield Park so rich for controversy and contention. Neither the narrator nor Austen herself can be nailed down. Yet, few can argue against Austen’s more obviously humorous passages and the hilarious traits she gives to some of her characters. Lady Bertram’s ennui, Mary Crawford’s wit, and less memorable, but equally shining moments that nod to Austen’s command of humor. Who else but Austen could successfully end Chapter 33, a chapter devoted to our heroine’s success at a ball, with Lady Bertram doling out a reward to Fanny.

“And I will tell you what, Fanny—which is more than I did for Maria—the next time Pug has a litter you shall have a puppy.”

We get a rollicking laugh out of this, but it’s no surprise that Fanny never gets her puppy. Smile upon smile—Lady Bertram is so indolent she hasn’t even named her own pug dog.

As we all know, but may not always have top of mind, this layering effect of Austen’s writing is what makes her a joy to read and reread.

One of the most humorous passages that’s often overlooked is the passage in Chapter 38 devoted to the coveted “silver knife” that Betsey and Susan squabble over. Mrs. Price’s botched involvement only ratchets up the humor by mirroring her equally inept sister in the parenting department. Yet, the humor here with the silver knife is, as is so often the case in Mansfield Park, I have to say—tarnished—with sadness. It’s funny but tragic that the two sisters fight over a knife. They clearly have no other, more suitable object for two young girls to fight over, and, worse, Susan inherited the knife from their dead sister Mary.

Austen’s gift for humorous description, and her tremendous powers of observation arise again and again throughout Mansfield Park, but take a careful look at the following paragraph that helps set us up for the much-needed relief that comes with the “cordial” letter from Edmund announcing he will be there to whisk Fanny and Susan away to Mansfield Park. These paragraphs also set us up for the comic relief of the cordial line. Austen does a phenomenal, and I would argue, darkly humorous, job of description here that makes Fanny’s liberation even sweeter. Austen, efficiently and seemingly effortlessly, describes the Price home for the final time through Fanny’s eyes:

“She [Fanny] sat in a blaze of oppressive heat, in a cloud of moving dust; and her eyes could only wander from the walls, marked by her father’s head, to the table cut and notched by her brothers, where stood the tea-board never thoroughly cleaned, the cups and saucers wiped in streaks, the milk a mixture of motes floating in thin blue, and the bread and butter growing every minute more greasy than even Rebecca’s hands had first produced it….”

Talk about layering! This paragraph is funny, but ugh, so perfectly revolting! Here’s to Austen’s sense of humor and her ever-so-thoughtful word choice in Mansfield Park and every novel she wrote. Let’s ring for a cordial.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Lynn Shepherd, Elisabeth Lenckos, and Sheryl Craig. This week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there’s one post per day.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 15, 2014

Why Tom Bertram Cannot Die

Thirty-third in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Tomorrow is Jane Austen’s birthday, and I’m celebrating all week long with guest posts on Mansfield Park every day. Please check back tomorrow when Karen Doornebos raises a glass to toast Jane Austen on her 239th birthday.

Today’s post is by Theresa Kenney. A member of JASNA and an Associate Professor of English at the University of Dallas, Theresa has written several essays for Persuasions. She has also published essays on Dante, Donne, Southwell, and Dickens. She edited and translated “Women Are Not Human”: An Anonymous Treatise and Responses, and co-edited and contributed to The Christ Child in Medieval Culture: Alpha es et O! At Stanford, her dissertation research focused on Medieval and Renaissance nativity lyrics, but she has frequently taught the 19th century novel, Early Modern literature, and Arthurian romance. Always missing her native Pennsylvania, she tells me, she and her Irish husband live in Texas with their two daughters – “and make frequent trips to cooler climes.”

Today’s post is by Theresa Kenney. A member of JASNA and an Associate Professor of English at the University of Dallas, Theresa has written several essays for Persuasions. She has also published essays on Dante, Donne, Southwell, and Dickens. She edited and translated “Women Are Not Human”: An Anonymous Treatise and Responses, and co-edited and contributed to The Christ Child in Medieval Culture: Alpha es et O! At Stanford, her dissertation research focused on Medieval and Renaissance nativity lyrics, but she has frequently taught the 19th century novel, Early Modern literature, and Arthurian romance. Always missing her native Pennsylvania, she tells me, she and her Irish husband live in Texas with their two daughters – “and make frequent trips to cooler climes.”

Theresa and I first met at the 2006 JASNA AGM in Tucson, one of my favourite AGMs because it focused on – what else! – Mansfield Park. (And because it was in Arizona, so I got to visit with some relatives who are very dear to me.) It’s a pleasure to introduce her guest post on “Why Tom Bertram Cannot Die,” and, before we get to that topic, to share with you her account of how she discovered Jane Austen.

I came late to Austen! While the regular 10th grade classes were reading Pride and Prejudice, the advanced placement students were afflicted with Malamud and Faulkner; if it hadn’t been for a heavy dose of Shakespeare and metaphysical poets that year, I would never have liked English at all. I was fully intending to major in Italian and Classics as a freshman at Penn State when my best friends, Nan Runde and her husband Joe, who were grad students and had sung in the church choir with me, steered me toward the English major, though I did double major in Classics. Some time later, these same friends influenced the course of my life again when they insisted that I read Pride and Prejudice while I was visiting them shortly after they had graduated and moved to Connecticut.

I came late to Austen! While the regular 10th grade classes were reading Pride and Prejudice, the advanced placement students were afflicted with Malamud and Faulkner; if it hadn’t been for a heavy dose of Shakespeare and metaphysical poets that year, I would never have liked English at all. I was fully intending to major in Italian and Classics as a freshman at Penn State when my best friends, Nan Runde and her husband Joe, who were grad students and had sung in the church choir with me, steered me toward the English major, though I did double major in Classics. Some time later, these same friends influenced the course of my life again when they insisted that I read Pride and Prejudice while I was visiting them shortly after they had graduated and moved to Connecticut.

I remember nothing about my reaction to the opening chapters, or even to Mr. Darcy, but when Mr. Wickham told Elizabeth that he had a warm, unguarded temperament I could not stop laughing. Every time I remembered that passage, I laughed. From then on I was in love, in love with Austen’s bad characters and their self-congratulatory way of speaking. It must have been 1980, the same year that the wonderful televised version with Elizabeth Garvie and David Rintoul came on, and my sisters and I lived for each episode. Elizabeth Bennet displaced Shakespeare’s Rosalind and Beatrice as my favorite female character in literature. I then tried reading Emma, but I disliked Mr. Knightley and his preachiness, and I could not figure out what Emma saw in him. Silly me! Now he is my favorite Austen hero.

I also liked Edmund Bertram more than your average Austenite even when I first read Mansfield Park some years later, and that takes some explaining. Edmund is no one’s favorite Austen hero, largely because he spends most of the novel in love with the wrong girl (if you like Fanny) or the right girl whom he does not deserve (if you like Mary Crawford). But I always like to be directed by Jane Austen on these matters, and she has chosen him and not Henry Crawford for her hero.

I teach college aged boys all the time, so Edmund’s infatuation with Mary seems to me the most natural thing in the world – and his unrecognized attachment to Fanny (I am convinced by Juliet McMaster on this subject, largely because I came to the same conclusion on my own) is just the sort of blindness I have seen in my own students and even a brother or two of my own. Moreover, Austen seemed to me to be showing that his struggles at the end of the novel were rewarded not only by gaining Fanny, but also by gaining his brother Tom, who had never really cared much for him at all. That happened instead of the Cinderella ending of Edmund’s inheriting Mansfield Park and elevating Fanny to be mistress of it. And so Tom’s illness, which I had discussed with my friend Dr. Cheryl Kinney, became for me a key to understanding both men’s roles in the novel.

[You can read Juliet’s argument in her post “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?” and you can also read Cheryl’s discussion of “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off.’” – Sarah]

I have always been interested in the sibling relationships in Mansfield Park, which start out in an unpromising way with the initial twisted Cinderella story of the three Ward sisters, in which Aunt Norris and Mrs. Price seem to play the role of the ugly stepsisters. Sir Thomas and Aunt Norris’s discussion of the potential romantic relationships that could arise between the adopted Fanny and the two Bertram boys also makes us think about sibling relationships as much as romantic ones. When I ask my students if the boys’ relationship with Fanny is the same as that they have with their sisters, they start to realize that at least Edmund’s is not, and it also becomes apparent that the Bertram siblings are far from close. It is clear that Edmund and his sisters do not have much in common, just as it is clear that Tom and Edmund share very little in the way of values or interests. It does not seem that their mother was close enough to her siblings to care if she were separated forever from the youngest, Fanny’s mother, and the younger generation in both the Bertram and Price families have inherited a cold attitude toward relations.

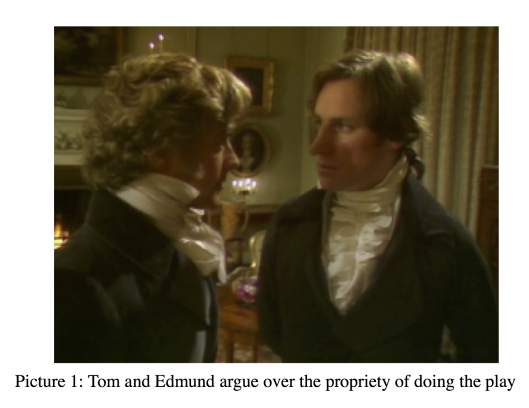

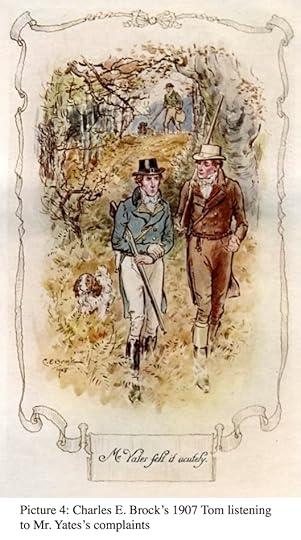

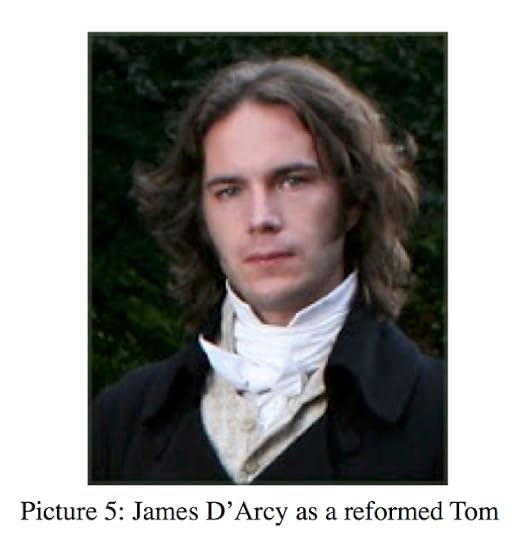

Edmund and Tom have a particularly important relationship in the novel, though Austen separates them and keeps Tom offstage a good deal of the time. Edmund often strikes readers as the elder of the two, and Mary Crawford even wishes for him to step into his elder brother’s place should Tom (as she hopes) die of the illness that afflicts him as part of the crisis and climax of the novel. However, though Edmund often arrogates authority to himself in conversations with his siblings and even with his mother and aunt, Edmund clearly has no wish to usurp Tom’s position as heir and future landowner. I would like to focus on significant communications that Edmund and Fanny share regarding Tom as the elder Bertram brother lies on his sickbed. Edmund’s notes to Fanny reveal an important change in Tom’s relationship with his younger brother:

. . . but when able to talk or be talked to, or read to, Edmund was the companion he preferred. His aunt worried him by her cares, and Sir Thomas knew not how to bring down his conversation or his voice to the level of irritation and feebleness. Edmund was all in all. Fanny would certainly believe him so at least, and must find that her estimation of him was higher than ever when he appeared as the attendant, supporter, cheerer of a suffering brother. There was not only the debility of recent illness to assist: there was also, as she now learnt, nerves much affected, spirits much depressed to calm and raise, and her own imagination added that there must be a mind to be properly guided.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 45 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2005)

Yes, Fanny does make some of her own imaginative additions, but Edmund’s narrative of his services to Tom in his letters emphasizes Tom’s depression and agitation. That Edmund is “all in all” may not be Tom’s phrase but Fanny’s, but she is reading between the lines with more than just an admirer’s discernment. As Edmund reveals the difficulty Tom has with the presence of his parents, he also reveals, without meaning to do so, how much Tom wants him and only him in the sick room. Edmund “attends, supports” and “cheers” him, proving to Tom what real friendship is when he has just suffered from the negligence of the London friends whose company he had previously preferred. Moreover, the narrator briefly confirms Fanny’s perception of Tom’s new regard for Edmund when Edmund returns to Mansfield after having fetched Fanny from Portsmouth: “Edmund was almost as welcome to his brother, as Fanny to her aunt . . .” (Chapter 47).

Edmund appears to the reader as the superior of the two brothers, healthy and protective when Tom is suffering and weak – and all this when he is crushed by the severest, the only, romantic disappointment of his young life. However, Austen still does not want to confirm Mary Crawford’s hopes and transform him into the future Sir Edmund. If Edmund succeeds in his task he will himself, personally, prevent a gap from opening up that would allow the author to slip him into the seat of secular power. Edmund reveals his moral strength and humility in nursing the sick, preserving Tom to lead Mansfield Park after Sir Thomas. Austen resolutely refuses to join with Mary Crawford in wishing “wealth and consequence” to be conferred upon her hero.

Thus, a changed Tom receives as a gift at the end of the novel a new appreciation of the goods Edmund has always espoused, and a priest in his parish who is not only his most loyal supporter, but also a loving brother. His future sister-in-law is also not greedy for power or money that would come her way (unbeknownst to her) should Tom die. During Tom’s illness, she is “more inclined to hope than fear for her cousin, except when she thought of Miss Crawford; but Miss Crawford gave her the idea of being the child of good luck, and to her selfishness and vanity it would be good luck to have Edmund the only son.” Fanny has no such ambition for Edmund, although she values him so much more highly than Tom.

But Fanny need not worry, for no such good luck attends Miss Crawford; Jane Austen is the only fairy godmother of this book and her gift to siblings is that they love each other and live and enjoy that affection. If Tom Bertram were to die, Austen could not show the power brotherly love might have not only in the family but also in the political world where church and state vie for highest status. Tom undergoes illness not to make way for the more meritorious Edmund, but because, as moral writer, Anglican priest Thomas Gisborne writes in “The Duties of a Clergyman,” “Sickness naturally disposes the mind to seriousness and reflection; and, by withdrawing its attention and loosening its attachment from the objects of the present world, fits it for estimating according to their real importance the concerns of that which is to come” (An enquiry into the duties of men in the higher and middle classes of Society in Great Britain: Resulting from Their Respective Stations, Professions, and Employments [London: B & J White, 1795]).

Though critics have neglected Tom, his creator Jane Austen says, “Tom became what he ought to be, useful to his father, steady and quiet, and not living merely for himself” (Chapter 48). From the demanding Jane Austen, that is high praise indeed, and confirms that by the end of the novel, it is not only Edmund who deserves to be entrusted with a great responsibility.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Karen Doornebos, Lynn Shepherd, and Elisabeth Lenckos.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 12, 2014

Tantrums and Toasted Cheese: On Saying NO to Boys of All Ages

Thirty-second in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Amy Patterson is recognizable to many Janeites as one of the three fabulous women behind the Jane Austen Books tables at JASNA AGMs. When she’s not selling books in person or online, she writes for Jane Austen’s Regency World Magazine , and works on long-term writing projects. Amy says she’s currently in the “slow-but-steady process” of blogging her recent trip to England at her site amylpatterson.wordpress.com . Last week she wrote about her visit to the beautiful town and bookshops of Hay-on-Wye in Wales, where she bought a lot of books and forgot what century it is.

She tells me she enjoys “reading, baking, and life with the two craziest little boys around.” Since Amy knows a great deal about both Jane Austen and kids, I interviewed her last year about introducing children to Austen and her novels. I’m very happy to introduce her guest post on the toasted cheese in Portsmouth.

Fanny, fatigued and fatigued again, was thankful to accept the first invitation of going to bed; and before Betsey had finished her cry at being allowed to sit up only one hour extraordinary in honour of sister, she was off, leaving all below in confusion and noise again; the boys begging for toasted cheese, her father calling out for his rum and water, and Rebecca never where she ought to be.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 38 (www.pemberley.com)

Oh, those boys. I feel for Mrs. Price. Boys certainly do beg for toasted cheese. And they certainly do ride around on earth in a clamor of “confusion and noise.” They are like little gods descending from the sky on clouds of chaos, demanding fealty from anyone in the house who can reach the refrigerator. My youngest, Charlie, once famously commanded me: “Mom! Get back in yours kitchen and make mine dinner!” I smiled patiently, and informed him that he would have to wait just like the rest of us.

Little boys are hardly the perfect companions for one in Fanny’s state of mind at the end of Chapter 38. Her punishment, the annihilation of peace and solitude, is a fitting representation of the future annihilation of such comforts that will take place if she submits to Sir Thomas’s will and marries Henry Crawford. The wilds of a low-rent Portsmouth establishment are as true a test as any given to an Austen heroine. Fanny of course passes the test through moral strength and spiritual fortitude, but after seeing her family up close it’s hard for the reader, and for Fanny herself, to figure out where these qualities come from.

Through Fanny’s eyes, we see Mrs. Price as a woman without the capacity to do much at all to help her children other than pet and hover over her favorite one. Mrs. Norris complains on her sister Price’s behalf that her inability as a parent is due to the multitude of children she’s had, but evidence suggests that Mrs. Price would probably not make a great mother to a smaller number of children, regardless of her wealth or status.

As Fanny’s stay in Portsmouth lengthens, she discovers that there is not much difference between Lady Bertram and her own mother, both listless personalities. Fanny, blinded by the bit of affection she’s received from Lady Bertram, perhaps doesn’t make the connection that her benefactress is just as neglectful a parent as Mrs. Price – only Lady Bertram has Aunt Norris for assistance, while Mrs. Price has poor, useless Rebecca.

In Chapter 39, the narrator laments that Fanny “must and did feel that her mother was a partial, ill-judging parent, a dawdle, a slattern, who neither taught nor restrained her children, whose house was the scene of mismanagement and discomfort from beginning to end.” Lady Bertram’s house would be the same if not for her income and status – in other words, without a hanger-on like Aunt Norris, whose zeal overcomes any mismanagement by Lady Bertram. It’s hard to imagine a young Edmund creating havoc and demanding food and treats, but as for the rest of the Bertram children, it’s not a leap to believe that their demands were constant, and most likely fulfilled only by their overbearing Aunt, instead of ignored by a dawdle of a mother or achieved half-heartedly by a lazy maid.

But somehow a few of the adult children of both mothers manage to make it into adulthood with their moral fortitude intact. Susan – even though she has spent her life with a disengaged, unaffectionate, ineffective mother and an alcoholic father – still knows what is right and wrong, and still works exasperatedly on her little brothers to behave themselves. Fanny is thoroughly good, as we see throughout the book, and William is an ambitious and bright young man eager to be of service to crown and country. As for their cousins – after Tom’s illness, he is almost as willing to be an upstanding heir as his brother Edmund. How can successful children come from such ineffective mothers? Is it as simple as the idea that “nature” is stronger than “nurture?”

Nature is pretty strong in little boys, and some of them never grow out of their need for physical fulfillment through food, play, or more worldly activities. The rambunctious little brothers at Portsmouth are a physical shock to Fanny’s system, but they are also a vivid reminder that there are men in the world whose nature has been combined with a profound lack of nurture, and that clamoring little boys who are spoiled by their mothers may be destined to grow into men who can’t take no for an answer. They are, in effect, miniature Henry Crawfords, unable to understand how their noise and their needs are unwelcome impositions on a mind seeking simple solitude.

As a mom of two such boys, the eldest of whom I just chased out of my office in tears because – I’m not kidding – he wants grilled cheese and it’s not dinner time yet, I hope all my nurturing will give me the right kind of Henry. (The Tilney kind, not the Crawford kind.) But I should probably get back in the kitchen and make some dinner before I think too hard about it.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Theresa Kenney, Karen Doornebos, Lynn Shepherd, and Elisabeth Lenckos. Next week, in honour of Jane Austen’s birthday, there will be one post per day, beginning on Monday.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

December 5, 2014

The Manipulations of Henry and Mary Crawford

Thirty-first in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Margaret C. Sullivan is the author of Jane Austen Cover to Cover: 200 Years of Classic Covers (Quirk Books, November 2014), which includes the two cover images of Mansfield Park shown below, plus dozens more covers of all of Jane Austen’s novels and juvenilia, encompassing two centuries of publication. You can see a few of the covers in these recent articles she wrote for The Guardian and The Huffington Post. I’m especially interested in the cover of Emma that features Mr. Elton instead of Mr. Knightley, and the cover of Pride and Prejudice that shows Lydia Bennet “tenderly flirting” with soldiers at Brighton.  Margaret is also the author of The Jane Austen Handbook (Quirk Books, 2007) and There Must Be Murder, a novella sequel to Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. She’s the founder of AustenBlog.com and loves to write metafiction about Jane Austen’s characters, such as the absolutely hilarious “League of Jane Austen’s Extraordinary Gentlemen” series – if you haven’t read it yet, I encourage you to do so, as soon as you finish reading her guest post on Henry and Mary Crawford. And then after that, you’ll want to read the dialogues she wrote to accompany some of the most absurd Austen covers ever produced.

Margaret is also the author of The Jane Austen Handbook (Quirk Books, 2007) and There Must Be Murder, a novella sequel to Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey. She’s the founder of AustenBlog.com and loves to write metafiction about Jane Austen’s characters, such as the absolutely hilarious “League of Jane Austen’s Extraordinary Gentlemen” series – if you haven’t read it yet, I encourage you to do so, as soon as you finish reading her guest post on Henry and Mary Crawford. And then after that, you’ll want to read the dialogues she wrote to accompany some of the most absurd Austen covers ever produced.