Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 32

September 9, 2014

Halifax, Nova Scotia in L.M. Montgomery’s Island Scrapbooks

L.M. Montgomery included many references to her time in Halifax, Nova Scotia in the “Island Scrapbooks” she created. I read Elizabeth Rollins Epperly’s book Imagining Anne: The Island Scrapbooks of L.M. Montgomery not long after it was published in 2008, but when I bought my own copy on a recent trip to Prince Edward Island, I decided to reread it in light of my new interest in the Nova Scotia connections in Montgomery’s life and work.

Lilacs at Village Pottery, New London, PEI, June 2014

Montgomery spent a year studying English at Dalhousie University, from 1895 to 1896, and she included an image of the main building with the caption “Dalhousie College, Halifax, the doors of which are wide open to women.” She received little encouragement from her family and friends when she chose to study at Dalhousie, and she must have been pleased to know that from the time it was founded in 1818, the university had never excluded women.

There are pieces of Dalhousie’s black and gold striped ribbon in two places in the Blue Scrapbook, on page 20 and tucked between pages 70 and 71, as well as a bit of ribbon on page 51 with the purple and gold colours of the Halifax Ladies’ College (and its successor, Armbrae Academy), where Montgomery boarded. The Red Scrapbook includes images of the interior and exterior of the Ladies’ College.

The Blue Scrapbook includes a card commemorating a New Year’s party held on Brunswick Street and a poem by Dalhousie English professor Archibald MacMechan entitled “My Lady of Dreams,” with this intriguing scrap of paper pasted beneath it: “What was the matter with the P.E.I. girl when she chased her room-mate through the window?” The juxtaposition between the poem and the question is intriguing. The poem is a meditation on lost love, dated “Saint’s Day, ’95,” written in a mood very different from the unanswered question, and the contrast is somewhat jarring. But that’s exactly the sort of effect Montgomery achieves in other places in the scrapbooks as she mixes “bright fragments” to “suggest metaphors and layers of story and feeling,” as Epperly says in her prefatory essay on “The Island Scrapbooks.”

The Blue Scrapbook includes a card commemorating a New Year’s party held on Brunswick Street and a poem by Dalhousie English professor Archibald MacMechan entitled “My Lady of Dreams,” with this intriguing scrap of paper pasted beneath it: “What was the matter with the P.E.I. girl when she chased her room-mate through the window?” The juxtaposition between the poem and the question is intriguing. The poem is a meditation on lost love, dated “Saint’s Day, ’95,” written in a mood very different from the unanswered question, and the contrast is somewhat jarring. But that’s exactly the sort of effect Montgomery achieves in other places in the scrapbooks as she mixes “bright fragments” to “suggest metaphors and layers of story and feeling,” as Epperly says in her prefatory essay on “The Island Scrapbooks.”

Montgomery’s “last examination,” written on April 17, 1896, is represented in the Blue Scrapbook – among the requirements were instructions to “Write a note on the use of the chorus in Henry IV,” “Justify the introduction of the comic characters in Henry IV Pts I & II,” and “Contrast the ‘rake’s progress’ of Falstaff and Prince Hal.” Dalhousie’s Convocation was held privately that year, Epperly says, “out of respect for the death of George Munro, a chief Dalhousie donor” (whose legacy is still commemorated each year in February when the University observes the Munro Day holiday).

Epperly remarks on the significance for Montgomery of the phrase “The Bend of the Road” (from the poem by Grace Denio Lichfield, reproduced in the Red Scrapbook), which she used as the title of the last chapter of Anne of Green Gables. She apparently shared Anne’s optimism about the future and what lies beyond that mysterious bend. Epperly says “many of Montgomery’s photographs were organized around a similar bend or curve: Montgomery’s and Anne’s beloved Lover’s Lane is frequently photographed and described with that provocative bend.”

Given my own interest in Montgomery and Point Pleasant Park, I was interested to find that the Notman Studio image of “A pretty bit of scenery in Point Pleasant Park, Halifax” in the Red Scrapbook also highlights a bend in the road along the shore.

A bend in the road at Point Pleasant Park, July 2014

You can read more about the images and poetry in the Island scrapbooks – and you can see a colour postcard of the bend in the road at Point Pleasant Park – in Christy Woster’s article in The Shining Scroll, “Clippings and Cuttings: Sources of Some of the Images and Poetry in L.M. Montgomery’s Island Scrapbooks.”

Melanie J. Fishbane is writing a YA novel based on the life of L.M. Montgomery, and she recently wrote a blog post about how she created a journal inspired by Montgomery’s scrapbooks.

I’ve finally put together a brand new page here on “L.M. Montgomery in Nova Scotia,” which lists all my blog posts on Montgomery, along with the books and essays I’ve been reading as I explore the connections between LMM and NS.

September 5, 2014

Forming Minds: Mind and Memory in Mansfield Park

Eighteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Lorrie Clark is an Associate Professor of English at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, where she teaches courses on Milton, eighteenth-century literature, Romanticism, history of the novel, tragedy, Jane Austen, and Joseph Conrad. She has published a book on William Blake, and she says initially she was especially interested in Jane Austen’s relation to Romanticism in Persuasion. I’m very happy to introduce her guest post on the “garden-gazing” scene in Mansfield Park.

“Mansfield Park has made me realize,” Lorrie says, “the extent to which Austen vigorously, consciously engaged in the eighteenth-century ‘Quarrel Between the Ancients and the Moderns’ about Aristotelian vs. modern scientific ideas of ‘nature,’ a quarrel with profound implications for understanding the foundation of morals in her novels. My blog post here attempts a small part of a much fuller argument on that subject published recently in Eighteenth-Century Fiction titled ‘Remembering Nature . . . in Mansfield Park’ (ECF 24:2, 2012).”

“Mansfield Park has made me realize,” Lorrie says, “the extent to which Austen vigorously, consciously engaged in the eighteenth-century ‘Quarrel Between the Ancients and the Moderns’ about Aristotelian vs. modern scientific ideas of ‘nature,’ a quarrel with profound implications for understanding the foundation of morals in her novels. My blog post here attempts a small part of a much fuller argument on that subject published recently in Eighteenth-Century Fiction titled ‘Remembering Nature . . . in Mansfield Park’ (ECF 24:2, 2012).”

Lorrie has reviewed numerous books on Austen (including my own Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues, in The Dalhousie Review), and she has given talks at several JASNA AGMs and Toronto JASNA chapter meetings. She says she’s really looking forward to the upcoming AGM in Montreal, “on what is certainly, because of its extraordinary depths, my favourite Austen novel.”

“This is pretty – very pretty,” said Fanny, looking around her as they were thus sitting together one day: “Every time I come into this shrubbery I am more struck with its growth and beauty. Three years ago, this was nothing but a rough hedgerow along the upper side of the field, never thought of as any thing, or capable of becoming any thing; and now it is converted into a walk, and it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or as an ornament; and perhaps in another three years we may be forgetting – almost forgetting what it was before. How wonderful, how very wonderful the operations of time, and the changes of the human mind!” And following the latter train of thought, she soon afterwards added: “If any one faculty of our nature may be called more wonderful than the rest, I do think it is memory. There seems something more speakingly incomprehensible in the powers, the failures, the inequalities of memory, than in any other of our intelligences. The memory is sometimes so retentive, so serviceable, so obedient – at others, so bewildered and so weak – and at others again, so tyrannic, so beyond control! – We are to be sure a miracle every way – but our powers of recollecting and of forgetting, do seem peculiarly past finding out.”

Miss Crawford, untouched and inattentive, had nothing to say; and Fanny, perceiving it, brought back her own mind to what she thought must interest.

“It may seem impertinent in me to praise, but I must admire the taste Mrs. Grant has shown in all this. There is such a quiet simplicity in the plan of the walk! – not too much attempted!”

“Yes,” replied Miss Crawford carelessly, “it does very well for a place of this sort. One does not think of extent here – and between ourselves, until I came to Mansfield, I had not imagined a country parson ever aspired to a shrubbery or any thing of the kind.”

“I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!” said Fanny in reply. “My uncle’s gardener always says the soil here is better than his own, and so it appears from the growth of the laurels and evergreens in general. – The evergreen! – How beautiful, how welcome, how wonderful the evergreen! – When one thinks of it, how astonishing the variety of nature! – In some countries we know the tree that sheds its leaf is the variety, but that does not make it the less amazing that the same soil and the same sun should nurture plants differing in the first rule and law of their existence. You will think me rhapsodizing, but when I am out of doors, especially when I am sitting out of doors, I am very apt to get into this sort of wondering strain. One cannot fix one’s eyes on the commonest natural production without finding food for a rambling fancy.”

“I am so glad to see the evergreens thrive!” said Fanny in reply. “My uncle’s gardener always says the soil here is better than his own, and so it appears from the growth of the laurels and evergreens in general. – The evergreen! – How beautiful, how welcome, how wonderful the evergreen! – When one thinks of it, how astonishing the variety of nature! – In some countries we know the tree that sheds its leaf is the variety, but that does not make it the less amazing that the same soil and the same sun should nurture plants differing in the first rule and law of their existence. You will think me rhapsodizing, but when I am out of doors, especially when I am sitting out of doors, I am very apt to get into this sort of wondering strain. One cannot fix one’s eyes on the commonest natural production without finding food for a rambling fancy.”

“To say the truth,” replied Miss Crawford, “I am something like the famous Doge at the court of Lewis XIV; and may declare that I see no wonder in this shrubbery equal to seeing myself in it.…”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 22 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1990)

Jane Austen’s novels are so exquisitely designed that we can see the whole novel in any given part. This makes it an almost overwhelming task to discuss this passage in a short blog post, but I’ll do my best!

This is one of only two “metaphysical” passages in all of Austen’s fiction. Both are in Mansfield Park: the celebrated “star-gazing” scene in which Fanny and Edmund reflect upon the beauty, order, and harmony of the night sky (Chapter 11); and this “garden-gazing” scene where Fanny reflects upon nature, including human nature, specifically, the human mind. I call these scenes “metaphysical” because through Fanny’s meditations Austen rises quite uncharacteristically to express her understanding of the universe and our place within it in ways that remain implicit in her other novels. This makes Mansfield Park the most explicit expression of Austen’s credo as an Aristotelian Christian, marking her “coming out” as an author as much as it marks Fanny’s coming out in society and Edmund’s ordination as a clergyman.

Fanny engages here in her most characteristic activity: reflecting aloud on nature and human nature. And while she often does this in solitude – alone on a garden bench at Sotherton (Chapters 9 and 10), or in her East room – she “converses” also with others, especially Edmund, and here, Mary Crawford. This scene in which, sitting with Mary, she gazes at Mrs. Grant’s garden and attempts to engage Mary in her “rhapsodizing” and “wondering” reflections on the beauties and mysteries of nature and human nature, contrasts greatly with the earlier star-gazing scene with Edmund. There, we experience with Fanny and Edmund a sense of profound harmony, tranquillity, and beauty, elevated to a shared sense of transcendence by “the sublimities of nature” understood as an ordered cosmic whole, one “Mind.”

Fanny engages here in her most characteristic activity: reflecting aloud on nature and human nature. And while she often does this in solitude – alone on a garden bench at Sotherton (Chapters 9 and 10), or in her East room – she “converses” also with others, especially Edmund, and here, Mary Crawford. This scene in which, sitting with Mary, she gazes at Mrs. Grant’s garden and attempts to engage Mary in her “rhapsodizing” and “wondering” reflections on the beauties and mysteries of nature and human nature, contrasts greatly with the earlier star-gazing scene with Edmund. There, we experience with Fanny and Edmund a sense of profound harmony, tranquillity, and beauty, elevated to a shared sense of transcendence by “the sublimities of nature” understood as an ordered cosmic whole, one “Mind.”

Here, by contrast, we experience not harmony but dissonance: Fanny’s reveries do not lift Mary into equally wondering, enthusiastic appreciation of nature as a universal whole or Mind. Mary is “untouched and inattentive”; she is distracted, absent-minded; her mind is wandering, much as she earlier jokes that young people’s minds “wander” when they are sitting in church (Chapter 9). She at first has “nothing to say” because she sees “no wonder in this shrubbery equal to seeing myself in it.” “Incurably selfish,” as she earlier cheerfully boasts about herself (Chapter 7), Mary is distracted by a vision of “self” that obscures any sense of a larger cosmic whole or “other” external to it.

Fanny, sensing this, first “[brings] back her own mind” from its reveries, and then attempts to bring Mary’s “mind” and attention out of its distractedness and inattentiveness by appealing to “what she thought must interest”: Mrs. Grant’s aesthetic “taste” in designing her garden walk. Fanny knows that both Mary and Henry Crawford are “aesthetes,” acutely attuned to the beauties of language and acting (Henry) and of music (Mary). The Crawfords appreciate all the “arts” – theatre, music, landscape gardening, architecture, fashionable dress – and are themselves “theatrical,” public performers as Fanny in her natural modesty, privacy, and humility is not.

Fanny’s ploy works: Mary is brought to respond, albeit “carelessly,” commenting that indeed she would never have expected a clergyman, a “mere nothing,” after all, to “aspire” “to a shrubbery or any thing of the kind.” She assumes clergymen are so humble, impoverished, and severely morally “virtuous” that they would never rise – or would that be, “fall”? – to the vanity and expense of an ornamental shrubbery in their gardens. (Edmund endorses such clerical severity in several places when he admits he’s too “plain-spoken” to be witty and amusing, his sermons aren’t delivered with sufficient “theatricality” of the sort that Henry has mastered, and he wants less “ornament” and more “utility” at Thornton Lacey.)

Yet Fanny takes equal if not even greater pleasure than the Crawfords in “prettiness” and “beauty,” that is, “aesthetics.” Her idea of “taste” however is not limited to merely aesthetic taste, the pleasures of the senses. For Fanny, the truly “beautiful” must have a kind of moral beauty about it: the moral beauty of “mind” that went into forming it with certain moral ends, intentions, or purposes behind it. She takes pleasure in Mrs. Grant’s moral character as expressed in the design of her garden: “There is such a quiet simplicity in the plan of the walk! – not too much attempted!” Most significantly, Mrs. Grant has recognized the inherent potential for “improvement” in something that may not have seemed to have much potential at all (“nothing but a rough hedgerow, … never thought of as anything, or capable of becoming anything”). Out of this apparent “nothing” she has made a garden walk that is both useful and beautiful: “it would be difficult to say whether most valuable as a convenience or as an ornament.”

This is of course an exact analogy of what Edmund’s tutelage in the Bertram household, together with her own reflections, have done for Fanny. Like Mrs. Grant, Edmund recognizes the inherent potential of what seemed a mere forgotten “nothing,” “a rough hedgerow,” to become “something,” “assisting the improvement of her mind, and extending its pleasures” (Chapter 2) such that she is now a young woman of whom it would be difficult to say whether she is most valuable for her usefulness or her newly emerging prettiness and graceful manners. Flourishing in her transplanted soil, she has blossomed into both: neither the merely useful “servant” Mrs. Norris wished to confine her to, nor just another polished but vacuously “ornamental” Bertram woman. Fanny has become that most morally beautiful and useful of human beings, a rationally critical yet also affectionately comforting “friend.”

The passage thus emphasizes the centrality of landscape gardening as one of several metaphors for education or “improvement” throughout the novel (the others being the Pulpit and the Theatre, extremes of severely moral vs. indulgently aesthetic education Austen rejects as such). Fanny notes that a certain species, the evergreen, flourishes better in Mrs. Grant’s garden than in her uncle’s because the soil there is better, like her own better flourishing when transplanted from Portsmouth to Mansfield Park. She also notes with wonder how plants “differing in the first rule and law of their existence” (deciduous vs. evergreen varieties) can nonetheless be nurtured by “the same soil and the same sun,” acknowledging by analogy the enormous “variety” of human nature, a natural inequality of potential that is perhaps shocking to our modern, egalitarian sensibilities. What is this “first rule and law of [our] existence” by which we “differ” both from other species and within our own?

Quite simply, our capacities of “mind” or memory, the faculty that Aristotle calls “nous.” In his view, as human beings, our highest capacity, our highest potential for human flourishing, health, and happiness – our highest pleasure, both moral and aesthetic – lies in the exercise of our minds, the activities of both practical and contemplative wisdom that Fanny so quietly yet strenuously “exercises” here and throughout the novel. Her own habits of mind, reflection, and memory are what she tries to instil in all the characters, attempting to give all of them, not merely Mr. Rushworth, a memory, a “brain,” a mind. This is the greatest force for “improvement” and “cure” in Mansfield Park; and what all of Austen’s novels are about: forming minds.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Laurel Ann Nattress, Elaine Bander, Maggie Arnold, and Hugh Kindred.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

August 29, 2014

Jane Austen’s “dead silence,” or, How Guilty is Sir Thomas Bertram?

Seventeenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

This is Deborah Barnum’s second post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.” In the first, back in May, she surveyed the publishing history of the novel: “‘I have something in hand…’ – The Publishing of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park.”

Deborah is a former law librarian, now owner of Bygone Books, a closed shop of fine and collectible books in Burlington, Vermont. She is currently the regional coordinator for the JASNA Vermont Region, author of the Jane Austen in Vermont blog, and compiler of the annual “Jane Austen Bibliography” for the JASNA journal Persuasions On-Line .

Mansfield Park cover (2012)

She says she’s “a firm believer that Mansfield Park is Austen’s greatest work, that Austen felt that way herself, and that because the comedy is overshadowed by the weight of tragedy, it is too often on the bottom of everyone’s favorites list.” And she adds that she’s happy to see my efforts to correct this! I’m grateful to her for lending her support to the cause, too. I trust you all like and appreciate Mansfield Park more than you did, say, this time last year, when we were all wrapped up in celebrating Pride and Prejudice and hardly had time to spare a thought for Fanny Price. I know my own appreciation for the complexities of the novel has been increasing over these last few months, as I’ve been learning so much from all of you. Thank you all for participating in this celebration by reading, writing guest posts, and commenting, and thank you, Deborah, for taking on the daunting task of analyzing the “dead silence” that follows Fanny’s question about the slave trade.

Please visit Deborah’s blog Jane Austen in Vermont, where she has compiled all the passages from Mansfield Park that relate to the slave trade or the West Indies/Antigua. She has also posted a bibliography for further reading on the topic of Mansfield Park and slavery, in which you can find more details about all the sources mentioned in this post.

[Edmund to Fanny] “Your uncle is disposed to be pleased with you in every respect; and I only wish you would talk to him more. – You are one of those who are too silent in the evening circle.”

[Fanny] “But I do talk to him more that I used. I am sure I do. Did not you hear me ask him about the slave trade last night?”

“I did – and was in hopes the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of farther.”

“And I longed to do it – but there was such a dead silence! And while my cousins were sitting by without speaking a word, or seeming at all interested in the subject, I did not like – I thought it would appear as if I wanted to set myself off at their expense, by shewing a curiosity and pleasure in his information which he must wish his own daughters to feel.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 21 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

Why I chose this passage, I have no idea! In these two words, “dead silence,” lies the crux of Mansfield Park – they are more analyzed as to the author’s intent than perhaps any other passage in all of Jane Austen. To understand this passage we need a thorough study of the slave trade and the history of the abolition movement in England; knowledge of the conditions of life for the owners and slaves in the West Indies, Antigua in particular; an in-depth view of Jane Austen’s personal connections to this slave-owning culture; some analysis of Austen’s political beliefs with thoughts that her allusions to the slave trade equal the condition of women in the early 19th century; and the generations of controversial critical analysis of this short passage. A heady task for a blog post!

So, I leave others to discuss these complex histories as I focus just on the “dead silence” passage and what Austen might be telling us about Sir Thomas and his connections to the slave trade, knowing full well it is a danger to take Jane Austen out of context – all is connected, each word essential to the whole, a tale told straight-forward but always with clues and nods to deeper meanings. I am doing Austen a disservice here, especially with this overcharged sentence, but I provide you here with a few questions to ponder the wider context of the novel and a bibliography for further reading.

Lord Mansfield, by Jean Baptiste van Loo, National Portrait Gallery (Source: Wikipedia)

Is Mansfield Park named after Lord Mansfield?

(You have perhaps all seen Belle, or read Paula Byrne’s book about the true story behind the movie?) William Murray, 1st Earl of Mansfield (1705-1793), and the Lord Chief Justice from 1756-1788, raised his two great nieces (see portrait below) Elizabeth Murray (whom Austen met a number of times, as noted in her letters) and Dido Belle, the daughter of Mansfield’s nephew John Lindsay and a slave named Maria Belle. In 1772, Mansfield ruled in the James Somerset case (also spelled Somersett) that no former slave could be removed from Britain and sold back into slavery. This and his ruling in the Zong case (the case portrayed in the movie) that human beings were not “property” were viewed as the beginning of the end of slavery on British soil.

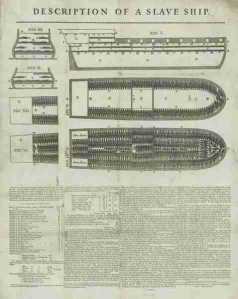

Austen surely knew of Mansfield’s rulings, as we know from her letters that she read Thomas Clarkson’s History of the Rise, Progress and Accomplishment of the Abolition of the African Slave Trade (1808) (see Letter 24, January 1813), and very likely chose this name for the house in Mansfield Park to make a clear statement of her slavery sentiments. (However, it is useful to look to John Wiltshire in his “Decolonizing Mansfield Park” where he gives us these two other options for the title: there is a Lady Mansfield who stays in Mansfield House in Austen’s favorite novel, Richardson’s Sir Charles Grandison (1753); and a book titled Amelie Mansfield, a French novel by Sophie Cottin, was first published in 1802.)

Elizabeth Murray and Dido Belle (Source: NPR)

Is Austen equating the slave trade to the condition of women in English society?

Jane Austen must have known of Hannah More’s 1805 pamphlet The White Slave Trade: Hints toward Framing a Bill for the Abolition of the White Female Slave Trade, in the Cities of London and Westminster, about young women “coming out” into society. The introduction of the “slave trade” into the text of Emma (see quotes on my blog) is even more telling here, equating the life of a slave with that of a governess, each really no more than property and badly treated.

Can the reader apply the metaphor of Mansfield Park = the State of the Nation, as many domestic novels of the time did? Fanny as slave, Sir Thomas as landlord/plantation owner, Mrs. Norris as his cruel agent – all fails when the Master is absent.

Was Austen a colonialist, an abolitionist, or both?

Edward Said’s interpretation of Mansfield Park (see bibliography) is the starting point for all discussion of this topic: he posits that Jane Austen was a product of her time, and the true daughter of an England that colonized and brutalized, and that she made only this off-hand nod to the slave trade to underscore her own lack of interest in it. That is, by returning her characters at tale’s end to the “tolerable comfort” of a restored Mansfield Park, Austen seems to condone the way of life it represents. We can read what she read, know what the sentiments were to slavery among her family and close connections, but we can only conjecture what she was intending in Mansfield Park. Is this novel a book about slavery? Or is this passage nothing more than a brief reference to the realities of life in England at the time Austen was writing?

Broadside: Description of a Slave Ship (from Clarkson’s book)

The Scene of the “dead silence”

Edmund and Fanny are discussing the change in the atmosphere at Mansfield Park since Sir Thomas’ return: all is “sameness and gloom,” and Edmund is lamenting the loss of the Parsonage company and their liveliness. Fanny (who we know to be happier without the Crawfords!), responds by saying

“the evenings do not appear long to me. I love to hear my uncle talk of the West Indies. I could listen to him for an hour together. It entertains me more than many other things have done….”

(Recall Fanny’s feelings of “dreadful duty” when first appearing before her uncle on his return.)

Edmund continues in response with the rather creepy chat about Fanny’s personal charms – her face, her figure – relating what his father has said of Fanny to him, and then we arrive at the “slave trade” comment (which is a tad ironic after the description of Fanny as a commodity – something to look at, appraise, and perhaps buy and sell?).

Then we have Fanny’s “dead silence” (such a strong phrase isn’t it?), followed by Edmund’s “it would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of further.” Fanny explains her reluctance to question further because she was afraid of slighting her cousins in their indifference to their father: “ – I thought it would appear as if I wanted to set myself off at their expense, by shewing a curiosity and pleasure in his information which he must wish his own daughters to feel.”

And then I find this very telling: Edmund goes on to talk of Mary Crawford, as uninterested in the slave trade as they all were the night before. (I am always rather appalled at Edmund. He might offer Fanny her only kindnesses, but he often forgets her quite easily, just as Tom Bertram does. Early on he finds her an “interesting object” [my emphasis]; he gives her horse to Mary without a thought; he never seems to stand up for her when she is constantly badgered by Mrs. Norris; he wishes her to marry Henry as much for himself to have a closer connection to Mary; and why, oh why, does he never insist on a fire in her room?? – but alas! This is a topic for another post….)

Who is Sir Thomas?

Harold Pinter as Sir Thomas (Patricia Rozema’s MP film, 1999)

The lack of response, the “dead silence,” to Fanny’s question has sent critics off into such contradictory analysis, one wonders if we have all read the same book. Jane Austen gives us very little to go on. We are told only that Mansfield is a “modern built house,” that Sir Thomas is a member of Parliament (but we don’t know if he is part of the established landed gentry or newly wealthy – he is awfully eager to marry off Maria to Mr. Rushworth with his money and connections), and that he has an estate in Antigua. We don’t know how long he has owned the estate, or whether indeed it is a sugar plantation dependent upon the slave economy (most critics assume that it is), or how dependent Mansfield Park is on the income from this estate (Mrs. Norris: “Sir Thomas’s means will be rather straitened, if the Antigua estate is to make such poor returns”). We don’t know exactly the dating of the action, which would help us understand the historical context of the tale.

All we do know is that Sir Thomas needs to go to Antigua to deal with issues that are causing “such poor returns.” He expects to be gone a year. Has he gone before, we might wonder? We only hear of his being gone to Town. He is, in the event, gone for two years, this fact often missed in the reading – he returns a changed man, physically and emotionally, and seems to enjoy talking about his time there (recall his comments later in the novel on the “balls of Antigua”). There was a life there among the colonial gentry and Fanny, unlike the rest of the family, enjoys hearing him talk of it.

So how do we look at Sir Thomas? He is the Master of Mansfield Park; he reigns over all, not unlike the Master on a slave-hold. The major issue of the West Indies plantations was the absentee landlord. The agent or overseer was often the abuser of the slaves and the money-matters and this was where many troubles began: sickness and loss of workers, slave rebellions, etc. Recall here Sir Thomas’s own words on the clergyman needing to live among his parishioners: “… if he does not live among his parishioners and prove himself by constant attention their well-wisher and friend, he does very little for their good or his own.”

Sir Thomas goes to Antigua to solve whatever problems are going on, and in so doing ironically leaves his English home in the hands of a cruel overseer, Mrs. Norris. Why she is so named is another of the Mansfield Park speculations: is she named for the anti-abolitionist slave trader John Norris of Liverpool (referred to by Clarkson), or as Wiltshire points out, is this name a satirical turn on “nourrice” / “norrice,” the French / English word for “to nourish” – certainly not our Mrs. Norris!

Why Antigua?

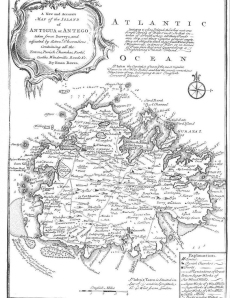

Map of Antigua (source: Gregson Davis article)

Having Sir Thomas absent from Mansfield for two years is of course a plot device. Austen could have used other storylines to send him away, but she does not – she sends him to Antigua. In Sir Thomas’s absence, all manner of ills beset Mansfield Park: the ridiculous Rushworth; the interloping Crawfords who disturb the peace of the “goodly heritage” (though we all are really glad they showed up!); the sexual undercurrents of the theatricals; Mrs. Norris’s cruel (though often funny) antics; Edmund’s obsession with Mary; Tom’s freedom from his father and his duties as elder son; and Henry’s harassing manipulation of Fanny – and the absentee Landlord/Master returns to find all in disarray.

Readings about the slave trade and slavery debates of the time make clear that Antigua was very different from the other slave-dependent colonies. William Wilberforce noted that slaves in Antigua were better treated and were given Christian instruction, which led to “happier” slaves. And not all plantation owners were part of the slave-holding lobby in Parliament. Many, as Christian sons of England, were opposed to the slave trade, believing that its abolition would lead to better treatment of the existing slaves, and that gradually slavery itself would “fade away” (see Boulukos).

Surely the close reader cannot really pass on all these references to Mansfield, Antigua, Norris, Austen’s favorite poet Cowper (a devout abolitionist), and the plot line of Fanny as slave, Sir Thomas as Master, as just coincidence – we know that Austen has no throw-away lines and these are not-so-subtle hints. It may not be clear that Sir Thomas as an MP is for or against the slave trade and slavery, but all these clues seem to indicate that Jane Austen was opposed to slavery and her Mansfield Park stands as her way of addressing the debate.

Is Sir Thomas a bad father?

Jane Austen did not do kindly by her living mothers, but her fathers are a sad and mostly awful lot as well. There are times I feel that Sir Thomas is the twin brother of General Tilney – certainly they are very close in their dictatorial parenting, unkind to their daughters who are treated as property. At other times he is like Sir Walter Elliot, overly concerned with his economic bottom-line and first impressions; he likes to retire to his own space much like Mr. Bennet (and lord knows what he really thinks of Lady Bertram! – it is clear that he does not like to play cards with her!); and though he is thankfully not a hypochondriac, he is often as self-absorbed as Mr. Woodhouse.

But unlike the other fathers, Sir Thomas is a more complicated figure. We don’t know enough about the conditions in and reasons for going to Antigua to really know what he is about. Readers often want to put him squarely in the available historical context of abolitionist-frenzied Britain to get a true sense of him. (Note that the slave trade was abolished in 1807-08 and a law for strict enforcement was passed in 1811, but slave labor in Britain was not abolished until 1833). The time-frame of the novel is important here: Chapman dates the main action as 1805-1809, during the height of the slave trade debate; Brian Southam dates it as 1810-1813, after the passage of the laws, at a time when the country was dealing with the effect of the new laws.

We may too easily look on Sir Thomas as a generous man to his wife’s poor relations: he takes in Fanny and helps William. But Austen is clear in describing him as doing it all for selfish reasons – all to feel good about himself. And lest we forget, Fanny is basically an unpaid servant.

Guilt by “silence”?

If we return to the passage, we find Fanny in her usual self-deprecating mode. By not pursuing the “slave trade” question, she is afraid of “[setting] myself off at their expense, by shewing a curiosity and pleasure in his information which he must wish his own daughters to feel.” (Fanny has certainly progressed from the ten-year-old Maria and Julia made fun of for her geographical failings!) And so ends the discussion. But why doesn’t Sir Thomas respond?? Edmund thinks he would welcome more questions, Fanny is “silenced” (her usual state), and we are left with a “Sir Thomas, guilty or not?” and the crux of the conversation about whether Mansfield Park is a book about slavery. Are we made to see, as surely as Sir Thomas does, that it is the “second-class” Fanny who has the gumption to ask the question not perhaps brought up in polite company, where all are rendered silent, much as the wider world chooses not to talk about it?

But I wonder this: Does Sir Thomas respond to Fanny? And Austen, as in her proposal scenes, leaves us out of the hearing? Looking at Austen’s words very closely: first we don’t actually know what Fanny asks about the slave trade – is she asking about its effect on the plantation, or about the slaves themselves, or is she asking about Sir Thomas’ stand on it all, or what the future might bring?

Then we have Edmund’s response: “I was in hopes the question would be followed up by others. It would have pleased your uncle to be inquired of farther” (my emphasis).

Fanny replies about the dead silence of her cousins and her wish not to outshine them “by shewing a curiosity and pleasure in his information which he must wish his daughters to feel” (my emphasis).

This seems to imply that Sir Thomas does respond to Fanny’s question, but then the dead silence of the rest of the company follows and Fanny chooses not to “inquire farther.” But Austen doesn’t allow us to hear what Sir Thomas says, and we are still left to speculate on his involvement in and views on the slave trade and slavery – and I think this is Austen’s point: she raises the question, but how does one answer it while living off the fruits of a slave-owning system?

“guilt and misery”

Fanny and Edmund, illustration by C. E. Brock (Source: Mollands)

Sir Thomas, of course, is severely “punished” by Austen at the tale’s end. Mansfield Park still stands, the income for now secure, or so it seems, but he is a less dominant force, made aware of his failings through a passage into self-knowledge: he loses Maria and Mrs. Norris to their sad destiny (and thankfully Susan arrives to take on Lady Bertram duty); Julia is lost to Mr. Yates; Tom the profligate heir might be improved and at last helpful, but will he give Mansfield the heir it needs to continue as it has?; and Edmund wins Fanny, now Sir Thomas’s true daughter (but not the mistress of Mansfield as many writers proclaim).

Austen, always the wit, prefaces her doling out the Fates with: “Let other pens dwell on guilt and misery. I quit such odious subjects as soon as I can, impatient to restore every body, not greatly in fault themselves, to tolerable comfort, and to have done with all the rest.”

And the Great Summing Up begins – reminding us that this is a Fiction, a comedy of sorts, its characters are of her Imagination, and she can end it how she chooses. We don’t know what happens after page 473, and perhaps Austen didn’t know either. But it was clear to her that the world of the landed gentry with its obsession with elder sons and inheritance, and the economic funding of a land dependent upon slave labor to sustain itself, was entering a time of great change.

We can look at Mansfield Park as a Cinderella story, complete with the wicked stepmothers and stepsisters and a variety of Regency shenanigans thrown in, and marvel how it all works out in the end with the proper (if dull) Prince (but alas! not the eldest son as Mary so lamented). Or we can look at it as an allegory of a system of patriarchy that controlled the lives and limbs of all the “inferior” beings (that is, slaves, wives, daughters, errant sons, servants) they depended upon to sustain their way of life. I am confused by Sir Thomas, am at turns horrified by him, and then sympathetic towards him – he is a contradiction, surely a product of his time and all too human, and I see here Austen with her broad strokes, posing the questions, challenging us in our turn to not be silent, to not be guilty of inattention….

I have not mentioned Patricia Rozema’s 1999 Mansfield Park film – I love this movie, I love seeing Fanny’s strengths made visible, finding Fanny as Jane Austen, Writer. But the slavery subtext that is made so very visually explicit in this movie, strongly so and not easy to forget, is, I remind you, not in the book….

What are your thoughts on Sir Thomas and the “dead silence” response to Fanny about the “slave trade”?

Please visit Jane Austen in Vermont for more information related to this post:

Mansfield Park text references to the slave trade, Antigua and the West Indies, and slavery.

Bibliography of further reading on the topic of Mansfield Park and slavery.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Laurel Ann Nattress, Lorrie Clark, Elaine Bander, and Maggie Arnold. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

August 22, 2014

The Scene-Painter

Sixteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

I can’t wait to see “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” a play written by Diana Birchall and Syrie James for the JASNA AGM in Montreal. The play stars many people familiar to JASNA members, including several contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park ”: Juliet McMaster, Natasha Duquette, Karen Doornebos, and Diana and Syrie themselves.

If you’ve been following this series, you’ll remember Juliet’s post “Is Edmund right about anything?” from a few weeks ago. You’ll get to read the guest posts by Natasha, Syrie, and Karen this fall – Natasha’s writing about Fanny Price and “the heroism of principle,” Syrie’s writing about the scene in which Fanny resists Sir Thomas’s attempt to persuade her to accept Henry Crawford’s proposal, and Karen’s writing about the moment at which Fanny finds herself in want of a “cordial.” And today, I’m very pleased to share with you Diana Birchall’s take on the scene-painter who comes to Mansfield to assist in preparations for the performance of “Lovers’ Vows.”

If you’ve been following this series, you’ll remember Juliet’s post “Is Edmund right about anything?” from a few weeks ago. You’ll get to read the guest posts by Natasha, Syrie, and Karen this fall – Natasha’s writing about Fanny Price and “the heroism of principle,” Syrie’s writing about the scene in which Fanny resists Sir Thomas’s attempt to persuade her to accept Henry Crawford’s proposal, and Karen’s writing about the moment at which Fanny finds herself in want of a “cordial.” And today, I’m very pleased to share with you Diana Birchall’s take on the scene-painter who comes to Mansfield to assist in preparations for the performance of “Lovers’ Vows.”

Diana is a story analyst at Warner Bros., reading novels to see if they would make movies. She is also the author of a scholarly biography of her grandmother, the first Asian American novelist, Onoto Watanna (University of Illinois Press), and several “Austenesque” novels, including Mrs. Darcy’s Dilemma and Mrs. Elton in America (Sourcebooks).

A couple of months ago, at the used book sale put on by Women for Music at the Halifax Forum, I picked up a collection called New Women: Short Stories by Canadian Women, 1900-1920, edited by Sandra Campbell and Lorraine McMullen, and was delighted to discover a story by Onoto Watanna (also known as Winnifred Eaton Reeve) alongside stories by L.M. Montgomery, Nellie McClung, and several others. I enjoyed reading the story of “Miss Lily and Miss Chrysanthemum,” two sisters reunited in Chicago after being brought up separately, Lily/Yuri in America by her father, and Chrysanthemum/Kiku in Japan by her mother. And after reading about the author’s friendship with Edith Wharton, one of my favourite writers, and her years of living in Alberta, one of my favourite places, I’m now even more keen to read Diana’s biography of her grandmother.

Diana has also written and produced several Jane Austen-related comedy plays, and she blogs at www.lightbrightandsparkling.blogspot.com.

Diana has also written and produced several Jane Austen-related comedy plays, and she blogs at www.lightbrightandsparkling.blogspot.com.

“The scene-painter was gone, having spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied….”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 20 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

“My father is come!” Illustration by Hugh Thomson.

For over forty years, longer than Jane Austen’s own lifespan, I have studied her works and her life: ardently, faithfully, and never getting to the bottom of her (so to speak). What have I learned? That there is ever more to learn; that deep acquaintance with one subject has its own deep rewards; and that in choosing to devote my life’s study to Jane Austen, I have chosen well.

Along the way, although not an academic, I have developed my own method of study. Probably many others have pursued the same path and it’s got a name, I just don’t know it. Rather than close reading, you might call it close writing. For me, it began in 1985 when I won a contest in Persuasions, imitating Jane Austen’s style. Obviously one can’t, but I had fun trying to “do” a bit of Miss Bates, and I was surprised to find that I had actually learned by doing this exercise … something about the elegant balance of her sentences. So I kept on, doing pastiche, sequels, continuations, whatever you like to call them. And with each one, I learned more. In writing about Mrs. Elton, I observed how deliberately Jane Austen framed her as a monster, while treating the erring Emma gently. Considering Lady Catherine, I became engrossed by how vastly different her aristocratic influences would have been, compared to those of the middle class characters – or to Austen’s own. Her very rotund, rolling speech announces her class.

This year being the year of Mansfield Park I have (heaven help me) been spending my time with Mrs. Norris. One of the nastiest of Austen’s characters (and I do seem to be attracted to the monsters, for what subconscious reasons I don’t want to know), she is for me one of the hardest to understand. What has embittered her? Does she import Fanny on the principle of a monstrous midlevel manager who wants an intern to bully? One thing is clear, she feels she has been cheated in life, and she doesn’t mean to let anyone else be happy if she can help it. I hope I can finally understand her by October, as I am to portray her in the staged reading of the play I wrote with Syrie James, “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” at the JASNA AGM in Montreal. But I fear it is too late now: her psychology remains a closed book to me.

It was while I was trawling around in the greenroom at Mansfield Park, a silent observer like Fanny, that I suddenly noticed the Scene-Painter, almost for the first time. He is the most minor of characters, mentioned in only two sentences, and yet such is Jane Austen’s skill that she paints him whole in just that space. He is a stranger and alien presence at Mansfield Park, a disruptive presence too, who in just a short time causes damage all out of proportion (almost like the Crawfords!), ruining the floor, the sponges, and the servants. What a story in microcosm! And what an unusual character for Jane Austen to introduce. Socially, what is he? He belongs to no world she has ever shown us before. It is the world of Bohemia, which we may have imagined would not be something Jane Austen knew anything about.

But the Scene-Painter is not gentry, nor a workman like the carpenter. He comes from London (“Entirely against his judgment, a scene-painter arrived from town, and was at work, much to the increase of the expenses, and, what was worse, of the eclat of their proceedings”) and imports attitudes and ideas that are indeed dangerous to servants in a country house. His very presence even introduces “éclat.” What were these attitudes? Who was this scene-painter, what was he? Would he have come from Covent Garden, center of artistic bohemian London; might Jane Austen have seen such louche folk, while on strolls near her brother’s house in Hans Place?

As usual, I could not find a way to know and understand this Austenian bohemian through lit crit, but only through fiction.

So here, then, is the first part of a story I have written, entitled (no surprise) “The Scene-Painter.”

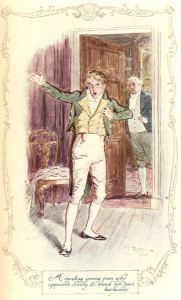

“A ranting young man who appeared likely to knock him down backwards.” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

The scene-painter arrived, and Tom introduced him to the party, quite as if he were a gentleman.

“My friend Robert Sharp,” he said, and Yates greeted him familiarly, though the others held back, and gave uncertain nods.

He was a very handsome young man, wiry and active in make, with sparkling dark eyes and long hair worn in what Fanny thought of as the poetical fashion, as she had seen in engravings of the “Lyrical Ballads” poets. He did not look like a workman at all.

Mr. Sharp made his bow in form, and did not appear to be at all embarrassed.

“I had quite a job getting here, Tom,” he remarked, “that hackney coachman wanted an amazing price for the drive from Northampton.”

“Oh, all that sort of thing will be reimbursed, Sharp, as I told you,” said Tom carelessly. “Just keep a list of your expenditures. Sharp, here,” he told the company with a rueful laugh, “is almost as expensive as Mr. Repton himself; but you don’t get artistic quality for nothing.”

Edmund, who had been watching with as much surprise and alarm as Fanny herself, quietly reminded his brother of their resolution to keep the costs of the play low.

“Oh! As to that,” said Tom, irritated by his look of disapproval as much as by his words, “you can depend on me not to be extravagant. But you cannot have a play without scenes, and Sharp here is the rising young theatrical artist. He is all the ton, I do assure you.”

“It runs in my family,” said the newcomer easily. “My father was a Royal Academician, and I grew up in the studios of the famous. Spent a good deal of time with Turner at Petworth, you know. It’s why I didn’t take a degree; my leaning was all for art, not academe.”

“No, I should say you weren’t academic,” Tom chuckled, “any more than myself or Yates here; I never could stand all that cramming, and my father knew better than to expect me to prefer Oxford to Newmarket.”

“But we don’t want the backdrops to look like Turner paintings, Tom,” protested Maria.

“Miss Bertram is right,” said Henry Crawford, “we want something more figurative.”

“It is Lovers’ Vows, you know, Mr. – Mr. Sharp,” said Maria, “a play translated from the German. Do you know it?”

Fanny was surprised by her cousin’s boldness at speaking to the new arrival so freely, and by her addressing him as a gentleman, not a servant. Meeting Edmund’s eyes, she saw he thought the same, but she supposed that Maria was merely following Tom’s lead.

“Do I know it! I see as many plays as I can, during the season,” he assured her with animation. “Lovers’ Vows is so popular, and has been performed so often, I could hardly fail to miss it. And, if I am not mistaken, do I have the honour of addressing an Agatha?”

“You do, sir,” and Maria made a courtesy.

“That’s my eldest sister, Miss Bertram, Sharp,” said Tom, adding in his friend’s ear, “engaged to Rushworth of Sotherton – a regular prize.”

“And I am to be the pert Amelia,” said Mary Crawford, with a smile.

“Miss Julia was to take the part, but she declined,” put in Yates, with a meaning look at Julia, who tossed her head.

“I do think you have made an excellent choice,” Sharp proceeded. “Lovers’ Vows is sentimental to be sure, and perhaps a trifle risqué, but it is a radical play you know, with some very modern ideas. I compliment you, Bertram, on having such an open-minded company. Free speech, free love. Quite revolutionary. I do approve.”

Mrs. Norris could keep quiet no longer. “I hope we are as open-minded as the next set of people,” she said, “but we are ladies and gentlemen, and I told you, Tom, not to attempt any play that is too warm. Sir Thomas would not like it.”

Tom waved a hand airily. “Do not be concerned, my dear aunt. Every thing ends up very morally in Lovers’ Vows, and it is no more dangerous than any play on the London stage. Natural sons, and things of that sort, are mentioned everywhere in polite society, nowadays. Now, Sharp, what ideas did you conceive for your scenes?”

“I was hoping there might be cherubs,” put in Mr. Rushworth, who had only been half listening. “I am to be very fine, you know, Sharp, in a blue dress, and pink satin cloak. I thought a background with flying cherubs, in similar colors, might flatter my clothing, if not myself. I know I am nothing to look at,” he finished with a deprecating laugh.

Sharp looked at him intently, and then said, “Is this Mr. Rushworth? Yes. Well, cherubs might be possible for one or two of the scenes. Something in the mode of Boucher, or Frangonard, you were thinking?”

Edmund interrupted. “Good heavens, Tom, we can’t be supporting major works of art here. We are to have a small budget, and get the play over with quickly. Of what are you thinking?”

“It need not take long at all,” said Sharp easily, “I can run you up some very fine cherubs in just a few days, I do assure you.”

“I hope you will cover them up,” Lady Bertram’s languid voice floated to them from her sofa. “The backs, especially, I always think.”

Every thing was said to assure Lady Bertram that all standards of decency would be preserved.

“More practically, Tom,” said Mrs. Norris, “where is Sharp to be housed while this is going on? There is room in the stable block, or he can share lodgings with the carpenter’s boy.”

“No, no,” said Tom hastily, “I see I have not made myself clear. My friend Sharp must be lodged the same as any other gentleman, of course – an artist, you know, is something quite apart from a workman. No, I was thinking of the second attic, upstairs; the one next Fanny’s white attic.”

“You mean to put him in the yellow attic?” considered Mrs. Norris. “There are some boxes … only some old things of your mother’s that I have been storing, but I never consider myself, or my needs. Yes, I suppose it will do, that is, if you are determined to have him in this house,” she conceded ungraciously.

“Indeed I am; and the yellow attic has the advantage of having a sky-light, so that he can do some of his painting there, and disturb no one.”

“That is well thought of,” Maria praised. “But who will look after him?”

Tom looked significantly at two of the maids, chattering while stitching away on Mr. Rushworth’s fancy costume in the corner. “Sarah, there, can look after him, I daresay, with Ellen to lend a hand. You won’t mind, girls. My friend Sharp will be very little trouble.”

The girls were young and pretty, and Edmund looked concerned.

“Tom, I would like to speak to you for a moment,” he said abruptly.

Reluctantly Tom allowed himself to be taken aside. “What do you know about this man’s reputation?” Edmund demanded. “Your introducing him amongst us like this, as a gentleman, seems a rash move.”

“Why, he is a gentleman. He can’t help it if he is also an artist, and needs to make some money; not everyone is heir to a landed estate you know, and his father was perfectly respectable, I do assure you.”

“And what was his mother?”

“Now Edmund, don’t be old-fashioned. What does it matter what a person’s mother was? I believe she was an actress, but Sharp’s papa is in the stud-book, and I’m not treating my friend as a servant.”

“Where did you meet?” asked Edmund, tight-lipped.

“Oh, well, I was in town with my friend Peebles, you have heard me speak of Peebles, Edmund. He knows no end of actresses and artists and dancers and all that sort of cattle, and they are a regularly lively set, I can tell you. You would like them yourself. I will take you to Sharp’s lodgings some time – you never saw such pretty girls in your life.”

“Such circumstances would hardly befit a clergyman that is to be, may I remind you,” said Edmund indignantly. “I think it is my duty to warn you to be careful of such acquaintance. You are playing with fire.”

“Oh, please, Edmund. I know what I am doing, and I beg you to remember you are my younger brother, and that I am master of the house while my father is not here.”

“That is not the point, Tom,” said Edmund, trying to keep his temper. “To speak plainly, you must be aware that we are responsible for the safety and morality not only of our sisters, but of our young female servants.”

“Why, Sarah and Ellen are good girls,” said Tom with a shrug, “nothing to fear for them.”

“But Sharp? Is he really a gentleman when it comes to ladies, Tom? It does not sound so, from what you say about actresses.”

“Good God, Edmund, why such a bother about nothing? They’re only housemaids! Haven’t you ever dallied with one of the girls?” Catching sight of his brother’s face, he muttered, “well, no, I suppose you never have.”

Edmund ignored this. “And what concerns me perhaps most of all, is that you have put him in the room next Fanny.”

“Why, you can’t think she would be susceptible to his charms!” Tom laughed immoderately at the idea.

“Nonsense, Tom. I wish you would take a serious view of all this. How can you think it proper to have this unknown – gentleman, if you will – so near to our cousin? Fanny is timid, you know, and what if he did … well, what if she were to hear something that would embarrass her?”

Tom lost patience. “Fanny is always hearing something that embarrasses her,” he exclaimed. “I’ll thank you to mind your own affairs, and I will attend to my friend, and his work, and his morals too, if you insist.”

“Very well then.” And Edmund had done, hoping that he had at least planted some thoughts into Tom’s mind.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Deborah Barnum, Laurel Ann Nattress, Lorrie Clark, and Elaine Bander. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

August 15, 2014

Jane Austen: Dramatist

Fifteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

This week’s guest post is by David Monaghan, Professor Emeritus at Mount Saint Vincent University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He’s the author of Jane Austen: Structure and Social Vision, the editor of Jane Austen in a Social Context and New Casebooks: “Emma” (all published by Macmillan) and co-author with John Wiltshire and Ariane Hudelet of The Cinematic Jane Austen (McFarland). When I was a graduate student at Dalhousie I had the good fortune to audit his class on Austen and film, and I’m very happy to introduce his post on that “ranting young man,” Mr. Yates.

“Then poor Yates is all alone,” cried Tom. “I will go and fetch him. He will be no bad assistant when it all comes out.”

“Then poor Yates is all alone,” cried Tom. “I will go and fetch him. He will be no bad assistant when it all comes out.”

To the theatre he went, and reached it just in time to witness the first meeting of his father and his friend. Sir Thomas had been a good deal surprised to find candles burning in his room; and on casting his eye round it, to see other symptoms of recent habitation and a general air of confusion in the furniture. The removal of the bookcase from before the billiard-room door struck him especially, but he had scarcely more than time to feel astonished at all this, before there were sounds from the billiard-room to astonish him still farther. Some one was talking there in a very loud accent; he did not know the voice – more than talking – almost hallooing. He stept to the door, rejoicing at that moment in having the means of immediate communication, and opening it, found himself on the stage of a theatre, and opposed to a ranting young man, who appeared likely to knock him down backwards. At the very moment of Yates perceiving Sir Thomas, and giving perhaps the very best start he had ever given in the whole course of his rehearsals, Tom Bertram entered at the other end of the room; and never had he found greater difficulty in keeping his countenance. His father’s looks of solemnity and amazement on this his first appearance on any stage, and the gradual metamorphosis of the impassioned Baron Wildenheim into the well-bred and easy Mr. Yates, making his bow and apology to Sir Thomas Bertram, was such an exhibition, such a piece of true acting as he would not have lost upon any account. It would be the last – in all probability the last scene on that stage; but he was sure there could not be a finer. The house would close with the greatest eclat.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 19 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

In order to properly explain my admiration for the paragraph that presents Sir Thomas Bertram’s on-stage encounter with Mr. Yates, I need to first go back a few pages and take a look at another theatrical moment. This occurs as the various dynamics that develop in the course of the amateur theatricals organized by the young people at Mansfield Park reach a point of crisis with Fanny Price’s capitulation to demands that she take a part in the play Lovers’ Vows. As rehearsals start up again and Fanny, stunned by the enormity of her moral compromise, experiences the “tremors of a most palpitating heart,” so Jane Austen saves the day with a deus ex machina in the form of Sir Thomas Bertram’s unexpected return from Antigua. Not only is Fanny spared but the theatricals and the dangerous relationships for which they have provided a cover are brought to a rapid conclusion.

In order to properly explain my admiration for the paragraph that presents Sir Thomas Bertram’s on-stage encounter with Mr. Yates, I need to first go back a few pages and take a look at another theatrical moment. This occurs as the various dynamics that develop in the course of the amateur theatricals organized by the young people at Mansfield Park reach a point of crisis with Fanny Price’s capitulation to demands that she take a part in the play Lovers’ Vows. As rehearsals start up again and Fanny, stunned by the enormity of her moral compromise, experiences the “tremors of a most palpitating heart,” so Jane Austen saves the day with a deus ex machina in the form of Sir Thomas Bertram’s unexpected return from Antigua. Not only is Fanny spared but the theatricals and the dangerous relationships for which they have provided a cover are brought to a rapid conclusion.

However, the decisiveness of the moment is illusory. Sudden interventions from outside are not the way things work in a Jane Austen novel. The role of deus ex machina is one that fits the patriarchal Sir Thomas’s self-image but Austen immediately calls its validity into question when, rather than follow theatrical convention and drop Sir Thomas into the centre of the action, she keeps him offstage, leaving it to the hysterical Julia to announce his arrival. Even more significant, we have only reached the end of the first volume and, beyond terminating the play, nothing of any real significance is resolved by Sir Thomas’s return.

In this instance, then, Austen is mocking theatrical convention and using it to point out the differences between her approach to story-telling – where resolutions are developed out of a gradual and complex process involving social interactions and decisions based on serious reflection – and one that relies on arbitrary and unexpected interventions from outside. How Austen might have actually used theatrical convention had she been writing plays rather than novels is indicated by the brief incident on which I mainly want to focus.

Even here, Austen never entirely strays from novelistic conventions and one of the delights of the scene is her decision, without precedent elsewhere in the novel, to filter the action through the consciousness of Tom, the character best qualified to see the funny side of his father’s discomfiture. Nevertheless, it is Austen’s exploitation of its theatrical possibilities that makes this scene, set appropriately on a stage, stand out.

“Mr. Yates rehearsing,” from an 1892 edition of Mansfield Park

First, building on her earlier debunking of the deus ex machina trope, Austen creates a few moments of dramatic business that give a humorous but pointed visual expression to Sir Thomas’s limitations as an authority figure. Initially bewildered by the chaotic state of his own room and the “hallooing sounds” emanating from next door, Sir Thomas enters the billiard room only to find himself on a stage where he is “opposed to a ranting young man, who appeared likely to knock him down backwards.”

Second, she again demonstrates her powers of visual representation in describing the “gradual metamorphosis [from] the impassioned Baron Wildenhaim into the well-bred and easy Mr. Yates,” a performance which is for Tom, here serving as a surrogate audience, “such a piece of true acting as he would not have lost on any account.” Delightfully comic in themselves, these few words are also extremely effective in pointing up the broader social implications of the emphasis placed on role-playing during the theatricals.

For a few brief moments, then, we gain a real insight into the type of plays that Austen might have written had she chosen a different means of artistic expression. Not for Austen, the contrived effects and melodramatic emotions of a theatre based on the tired conventions of classical drama. On the contrary, hers would have been witty and profound social comedies that allied the brilliant dialogue frequently to be found in her novels to a keen visual sense. It is the sheer delight of seeing a great artist switch briefly but with great effect into a different register that makes the paragraph discussed above my favourite in Mansfield Park.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Coming soon: guest posts by Diana Birchall, Deborah Barnum, Laurel Ann Nattress, and Lorrie Clark. Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party!

August 11, 2014

A Summer (Reading) Marathon

“A girl came out of lawyer Royall’s house, at the end of one street of North Dormer, and stood on the doorstep.” This is the first line of Edith Wharton’s 1917 novel Summer, a line that suggests something new and interesting is about to happen to that girl who’s about to venture out into the world. She sees a young man, a stranger, whose straw hat is lifted by the wind and blown into the duck-pond, and it’s easy to guess her encounter with this young man will change her life.

“A girl came out of lawyer Royall’s house, at the end of one street of North Dormer, and stood on the doorstep.” This is the first line of Edith Wharton’s 1917 novel Summer, a line that suggests something new and interesting is about to happen to that girl who’s about to venture out into the world. She sees a young man, a stranger, whose straw hat is lifted by the wind and blown into the duck-pond, and it’s easy to guess her encounter with this young man will change her life.

She goes out into the world, but only as far as the town library where she works, and where she’ll meet the handsome stranger when he enters to look for books on the history of houses in the area. This library is not the gateway to knowledge about architecture or anything else, however, but a “prison-house,” a “vault-like room” with “rows of rusty bindings” and “tall cobwebby bindings” – and no card catalogue.

The library in North Dormer is in disrepair, but even so, it reminds me of the grand library in Undine Spragg’s hôtel in Paris at the end of The Custom of the Country, in which the bookcases are all locked because “the books were too valuable to be taken down.” I wrote a blog post about that passage a couple of years ago because I was fascinated by Wharton’s vision of hell as a library in which no one is able to read or write.

The library in North Dormer is in disrepair, but even so, it reminds me of the grand library in Undine Spragg’s hôtel in Paris at the end of The Custom of the Country, in which the bookcases are all locked because “the books were too valuable to be taken down.” I wrote a blog post about that passage a couple of years ago because I was fascinated by Wharton’s vision of hell as a library in which no one is able to read or write.

When the girl in Summer, Charity Royall, thinks about the founder of the “queer little brick temple” called “The Honorius Hatchard Memorial Library,” she wonders “if he felt any deader in his grave than she felt in his library.” Twice in the first few pages of the novel, Charity says to herself, “How I hate everything!” Yet she can’t help being interested in the stranger – and “The fact that, in discovering her, he lost the thread of his remark, did not escape her attention.”

Summer and Ethan Frome, the two short novels Wharton set in western Massachusetts, were both more controversial than any of her other books (according to Candace Waid in Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld). Known as “the hot Ethan,” Summer is the story of a passionate love affair and its consequences. Wharton, says Marilyn French in her introduction to the Scribner edition, “has written a novel that is a clamorous and ecstatic affirmation of the joy of sexual love no matter what it costs.” And, she adds, “It does cost.”

Summer and Ethan Frome, the two short novels Wharton set in western Massachusetts, were both more controversial than any of her other books (according to Candace Waid in Edith Wharton’s Letters from the Underworld). Known as “the hot Ethan,” Summer is the story of a passionate love affair and its consequences. Wharton, says Marilyn French in her introduction to the Scribner edition, “has written a novel that is a clamorous and ecstatic affirmation of the joy of sexual love no matter what it costs.” And, she adds, “It does cost.”

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, MA, is hosting a marathon reading of Summer tomorrow, August 12th, and I wish I could be there. “Summer afternoon – summer afternoon.” As Wharton’s good friend Henry James said, “those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language” (quoted in Chapter 10 of Wharton’s autobiography A Backward Glance). Wouldn’t it be lovely to spend a summer afternoon reading Summer in the Berkshires?

The Mount, Edith Wharton’s home in Lenox, MA, is hosting a marathon reading of Summer tomorrow, August 12th, and I wish I could be there. “Summer afternoon – summer afternoon.” As Wharton’s good friend Henry James said, “those have always been the two most beautiful words in the English language” (quoted in Chapter 10 of Wharton’s autobiography A Backward Glance). Wouldn’t it be lovely to spend a summer afternoon reading Summer in the Berkshires?

Edith Wharton died on this date, August 11th, in 1937.

August 9, 2014

The First Three Months of the Mansfield Park Party!

With three months of guest posts on Mansfield Park, it’s possible that you might have missed a post or two. Maybe you missed the week where we looked at the link between a high fat diet and sudden death, or the weeks where we talked about whether Mary Crawford is “as bad as [her] brother,” or the weeks where we discussed whether Jane Austen could possibly have been talking about sodomy and whether she meant for us to understand those spikes at Sotherton literally or figuratively.

Maybe you’re just discovering the series, in which case — welcome! Or maybe you’ve been following along, but you’d like to go back to the first post on the opening paragraph and read everything in order.

Here’s a guide to everything that’s appeared so far in “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.”

Part 1: “Clarity and Complexity: Mansfield Park Begins,” by Lyn Bennett:

Far from famous, Mansfield Park’s first line doesn’t offer the memorable simplicity of “It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife.”

Part 2: “Adopting Affection,” by Judith Thompson:

Part 2: “Adopting Affection,” by Judith Thompson:

I have a secret to confess. I’ve always liked Fanny Price, even though she is generally agreed to be the most tight-ass heroine of the most conservative novelist of the romantic era, whereas I’m passionately in love with one of that era’s most kick-ass revolutionaries, the radical activist and atheist John Thelwall.

Part 3: “First Impressions of Fanny Price,” by Jennie Duke:

… with “nothing to disgust,” “no glow,” the description is largely about what she is not.

Part 4: “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off,’“ by Cheryl Kinney:

It would not be until the next century that the association between diet and sudden death was firmly and scientifically established. Jane Austen, without formal medical training, required no such length of time to come to the correct medical conclusion – that people who must have their “palate consulted in everything” (Chapter 11) and who indulge in “three great institutionary dinners in one week” (Chapter 48) would be at risk to suffer apoplexy and death.

Part 5: “Mary Crawford and the Mansfield ‘cure,’“ by Katie Davis:

This brief passage in Chapter 5 calls our attention to a few of the central questions of Austen’s novel: to what extent can the opinions and habits of fully-formed adults be changed – or “cured” – by entering into community with people whose opinions and habits are, in crucial ways, totally different? What is required for such a transformation?

Part 6: “Scattering Seeds of Kindness,” by Mary C.M. Phillips:

Part 6: “Scattering Seeds of Kindness,” by Mary C.M. Phillips:

Random acts of kindness may often come from the most unlikely of characters. An ambitious social climber might have a better eye for injustice than even the most sincere clergyman. To some, Mary Crawford, the charming antagonist of Mansfield Park, is considered shallow, immoral and unprincipled. But not to me.

Part 7: “A Gentleman’s Improvements: Mr. Rushworth, Humphry Repton, Fanny Price and Fashionable Landscaping,” by Jacqui Grainger:

Wealth and status, power and the responsible use of money are persistent themes in the work of Jane Austen. Austen uses the idea of improvement to reflect varying attitudes to money and its appropriate disposal.

Part 8: “Rears and Vices,” by Devoney Looser:

Part 8: “Rears and Vices,” by Devoney Looser:

To suggest that there is sex in Mansfield Park – at least in the way that recent film and television adaptations tend to – is rubbish. … That said, there is sexuality (even dangerous, illicit sex) in Mansfield Park, albeit between the lines.

Part 9: “Something from Nothing,” by Mary Lu Roffey Redden:

Mary Crawford’s reply to Edmund’s planned ordination may be cynical about the church – “A clergyman is nothing” – but she is also surprisingly insightful about issues that still resonate for clergy: what is the difference between a vocation that may mean relative poverty and social obscurity and a profession in which one seeks advancement, a good salary and some social standing?

Part 10: “The Fatal Mistake,” by Deborah Yaffe:

Part 10: “The Fatal Mistake,” by Deborah Yaffe:

How do we know that Maria’s unwillingness to wait for Rushworth to bring her the key to the gate prefigures her unwillingness to remain faithful to him within the fenced wilderness of marriage?

Partly, of course, we know all this because we are post-Freudian readers, primed to see keys and spikes and tears as sexual codes. How, then, do we know that the pre-Freudian Jane Austen had this metaphorical reading in mind?

Part 11: “Dr. Grant’s Green Goose,” by Julie Strong:

Dr. Grant is a grouchy gourmand whom Austen summari ly dispatches at the close of the novel.

ly dispatches at the close of the novel.

Part 12: “Is Edmund Bertram right about anything?” by Juliet McMaster:

… what interests me is the extent to which Edmund’s piece of wisdom may actually apply to himself. I have long believed that Edmund, even while he consciously courts Mary Crawford, is equally in love with Fanny – or indeed even more so.

Part 13: “Angry White Female: An Apology for Mrs. Norris,” by George Justice:

In a novel with unclear heroes and heroines, Mrs. Norris is—or would seem to be—an unambiguous villain. She is mean-spirited, self-serving, erroneous, obsequious: fully hideous.

Part 14: “Austens Ands, Ors, and Buts,” by Lynn Festa:

Part 14: “Austens Ands, Ors, and Buts,” by Lynn Festa:

Conjunctions both join and sunder: they yoke individual words or the separate clauses of a sentence together, but they are also physically interposed between the parts they are supposed to unite. In this passage, conjunctions serve as barriers as much as bridges: “and” fails to conjoin; “or” fails to offer viable alternatives; and “but” fails to make an exception or mitigate the lack of connection it seeks to overcome.

All the contributions are also listed on this page, “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” along with many other essays on the novel published elsewhere on the web. If you’re on Pinterest, you might be interested in my Mansfield Park board. And I also talk about the novel on Facebook and Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley).