Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 31

October 17, 2014

The Comfort of Friendship

Twenty-fourth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Margaret Horwitz specializes in Film Studies, and has given many talks on Jane Austen’s novels and their film and television adaptations. She spoke at the JASNA AGMs in Los Angeles (2004) and Chicago (2008), and was JASNA’s Traveling Lecturer for the western part of North America in 2008-2009. She has a Ph.D. in Film Studies from UCLA and is a visiting professor of literature for New College Berkeley, an institute of the Graduate Theological Union. She’s a Life Member of JASNA and has been active in JASNA circles since the mid-1990s, first in Southern and then Northern California.

I met Margaret at the 2005 AGM in Milwaukee, where we discovered that we share an interest in the prayers Jane Austen wrote, and in questions about ethics in Austen’s novels. It was wonderful to see her in Montreal last weekend at the Mansfield Park AGM, and I’m very pleased to introduce her guest post on Fanny Price’s feelings about the two necklaces given to her by Mary Crawford and Edmund Bertram.

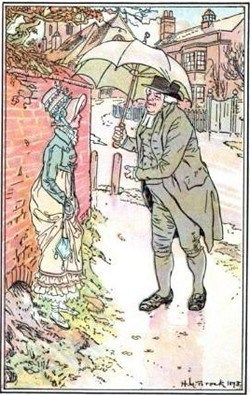

“Oh, this is beautiful, indeed!” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

“Dearest Fanny!” cried Edmund, pressing her hand to his lips with almost as much warmth as if it had been Miss Crawford’s, “you are all considerate thought! But it is unnecessary here. The time will never come. No such time as you allude to will ever come. I begin to think it most improbable: the chances grow less and less; and even if it should, there will be nothing to be remembered by either you or me that we need be afraid of, for I can never be ashamed of my own scruples; and if they are removed, it must be by changes that will only raise her character the more by the recollection of the faults she once had. You are the only being upon earth to whom I should say what I have said; but you have always known my opinion of her; you can bear me witness, Fanny, that I have never been blinded. How many a time have we talked over her little errors! You need not fear me; I have almost given up every serious idea of her; but I must be a blockhead indeed, if, whatever befell me, I could think of your kindness and sympathy without the sincerest gratitude.”

He had said enough to shake the experience of eighteen. He had said enough to give Fanny some happier feelings than she had lately known, and with a brighter look, she answered, “Yes, cousin, I am convinced that you would be incapable of anything else, though perhaps some might not. I cannot be afraid of hearing anything you wish to say. Do not check yourself. Tell me whatever you like.”

They were now on the second floor, and the appearance of a housemaid prevented any farther conversation. For Fanny’s present comfort it was concluded, perhaps, at the happiest moment: had he been able to talk another five minutes, there is no saying that he might not have talked away all Miss Crawford’s faults and his own despondence. But as it was, they parted with looks on his side of grateful affection, and with some very precious sensations on hers. She had felt nothing like it for hours. Since the first joy from Mr. Crawford’s note to William had worn away, she had been in a state absolutely the reverse; there had been no comfort around, no hope within her. Now everything was smiling. William’s good fortune returned again upon her mind, and seemed of greater value than at first. The ball, too – such an evening of pleasure before her! It was now a real animation; and she began to dress for it with much of the happy flutter which belongs to a ball. All went well: she did not dislike her own looks; and when she came to the necklaces again, her good fortune seemed complete, for upon trial the one given her by Miss Crawford would by no means go through the ring of the cross. She had, to oblige Edmund, resolved to wear it; but it was too large for the purpose. His, therefore, must be worn; and having, with delightful feelings, joined the chain and the cross – those memorials of the two most beloved of her heart, those dearest tokens so formed for each other by everything real and imaginary – and put them round her neck, and seen and felt how full of William and Edmund they were, she was able, without an effort, to resolve on wearing Miss Crawford’s necklace too. She acknowledged it to be right. Miss Crawford had a claim; and when it was no longer to encroach on, to interfere with the stronger claims, the truer kindness of another, she could do her justice even with pleasure to herself. The necklace really looked very well; and Fanny left her room at last, comfortably satisfied with herself and all about her.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 27 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003)

This passage from Chapter 27 of Mansfield Park intrigues me because it illustrates the power and comfort of friendship, and includes one of the most compelling moments in the novel. The setting of the passage begins near a staircase, and recalls a scene in Chapter 2 where Edmund Bertram notices the “despondence” of his ten-year-old cousin Fanny Price, shortly after her arrival at Mansfield Park. Edmund, who is six years older than Fanny, comforts her, while sitting next to her on the attic stairs. He then helps her write a letter to her brother William, who had been her advocate at home in Portsmouth. From the first recorded conversation between Fanny and Edmund, he and William are linked in their friendship with her.

This passage from Chapter 27 of Mansfield Park intrigues me because it illustrates the power and comfort of friendship, and includes one of the most compelling moments in the novel. The setting of the passage begins near a staircase, and recalls a scene in Chapter 2 where Edmund Bertram notices the “despondence” of his ten-year-old cousin Fanny Price, shortly after her arrival at Mansfield Park. Edmund, who is six years older than Fanny, comforts her, while sitting next to her on the attic stairs. He then helps her write a letter to her brother William, who had been her advocate at home in Portsmouth. From the first recorded conversation between Fanny and Edmund, he and William are linked in their friendship with her.

In Chapter 27, Fanny is now eighteen, and on the afternoon of the ball in her honor, a role reversal occurs in her friendship with Edmund. Though having cautioned him that she would not be an “adviser,” Fanny has agreed to be a “listener” as he struggles with uncertainty over the question of marriage to Mary Crawford. Edmund asserts, “I can never be ashamed of my own scruples,” in other words, the principles he has taught Fanny and which they now share. Edmund believes that “if they are removed” it must be by changes “in Miss Crawford’s conduct.” Yet his scruples have been to an extent diminished, since Edmund refers to Mary Crawford’s errors as “little,” though she has tried to convince him to renounce his calling as a clergyman.

Edmund acknowledges the unique place Fanny has in his life by saying, “You are the only being upon earth to whom I should say what I have said.” In spite of his many material advantages, she is the one person in whom he can confide. Fanny is then able to reply to Edmund with a “brighter look,” that she is convinced he would “be incapable of anything else” (adhering to his principles) though “some might not,” an indirect reference to Mary Crawford. This praise shows Fanny’s mettle as a friend to Edmund, since she expresses her faith in the strength of his character, though he is in love with and confused by her (unacknowledged) rival. In this way, Fanny also predicts the behavior of both Edmund and Mary Crawford.

Their conversation concludes before Edmund might “talk away all Miss Crawford’s faults” and his own “despondence,” the same word used for Fanny’s state of mind in Chapter 2. The role reversal in this passage continues because Edmund is now the recipient of Fanny’s kindness as they part ways, “with looks on his side of grateful affection,” in contrast to the pattern of his being kind and Fanny responding with gratitude. He also has affirmed her. From a place of “no comfort around” and “no hope within her,” Fanny can anticipate the ball that night as an “evening of pleasure,” instead of anxiety.

One of the most satisfying moments in the novel takes place when Fanny goes into her room to dress for the ball. Her “good fortune seemed complete,” when the ornate necklace Mary Crawford has given her cannot go through “the ring of the cross,” a gift to Fanny from William. The “plain gold chain” Edmund had just given her the prior evening “must be worn,” though he has urged her to wear the more elaborate necklace, in order to please Miss Crawford. The necklace, originally a gift to Mary from her brother, Henry Crawford, was imposed on Fanny with the injunction that she remember both of them in wearing it. In this instance, Fanny successfully navigates a series of competing claims. She is able to have her preference, “and with delightful feelings” to join “the chain and the cross, those memorials of the two most beloved of her heart, those dearest tokens.”

One of the most satisfying moments in the novel takes place when Fanny goes into her room to dress for the ball. Her “good fortune seemed complete,” when the ornate necklace Mary Crawford has given her cannot go through “the ring of the cross,” a gift to Fanny from William. The “plain gold chain” Edmund had just given her the prior evening “must be worn,” though he has urged her to wear the more elaborate necklace, in order to please Miss Crawford. The necklace, originally a gift to Mary from her brother, Henry Crawford, was imposed on Fanny with the injunction that she remember both of them in wearing it. In this instance, Fanny successfully navigates a series of competing claims. She is able to have her preference, “and with delightful feelings” to join “the chain and the cross, those memorials of the two most beloved of her heart, those dearest tokens.”

It makes sense that William and Edmund, Fanny’s closest friends as well as family members, honor her character and her taste, so that the chain and cross seem “formed for each other.” The chain’s simplicity is appropriate for Fanny’s integrity. The cross represents love and sacrifice in William’s purchasing a costly present, one which also recognizes Fanny as a person of faith.

Finally, unlike Mary Crawford’s necklace, Edmund’s gold chain is not given to her in the service of another relationship. He remembers what would be helpful to Fanny, something important to her comfort. Edmund has indeed shown himself to have a “truer kindness” than Mary Crawford, who has forced a gift on her. In addition to the chain and cross, Fanny makes the decision to wear Miss Crawford’s necklace, and even thinks it “really looked very well.” She leaves her room for the ball, “comfortably satisfied with herself and all about her.” Edmund’s friendship, and his response to her friendship, result in a rare moment of comfort for Fanny, who is undervalued and forgotten throughout much of the novel.

This passage reveals Edmund’s need for Fanny to listen to his conflicting feelings, as his sole confidante. Fanny is a steadfast friend in encouraging him to hold fast to his principles. Edmund’s ability to do so in the long run derives at least in part from their friendship as an important touchstone in his life. His unalloyed kindness to Fanny, in realizing her need for a chain to support William’s cross, is rewarded by these gifts complementing each other. The gift of a cross, itself a symbol of sacrificial love, also reveals William’s faithfulness in remembering Fanny as a sibling and friend during her eight years of separation from their childhood home. Though she still has much pain to endure, including Edmund’s wavering, I find this scene a high point in the novel. For once, Fanny “must” do what she most wishes, to unite these objects, “full of William and Edmund,” and by implication the two persons “dearest” to her comfort.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, Syrie James, and John Baxter.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 16, 2014

Listening to Mansfield Park

One of the many highlights of this year’s JASNA AGM in Montreal was definitely Lynn Festa’s plenary session on “The Noise in Mansfield Park,” in which she showed us why this novel is Jane Austen’s “noisiest book.” Fanny Price may appear to be a quiet heroine, but both her interior life and her exterior surroundings are anything but peaceful. Lynn talked about how “it’s very difficult to quote noise” because it’s something we hear, but don’t really listen to. In Mansfield Park, she suggested, Austen asks us to pay close attention to noise, to listen carefully.

The view from Mount Royal

It really was a fabulous weekend of listening to people talk about Mansfield Park, just as I expected it to be. (Here’s last week’s blog post on “Mansfield Park in Montreal,” with details about things I was looking forward to.) It was great to meet up with several of the contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” some of whom I met in person for the first time, after many conversations on-line. Many of our JASNA Nova Scotia members went to this year’s AGM, too.

It was a pleasure to attend talks by so many excellent speakers, including Juliet McMaster on “Female Difficulties: Austen’s Fanny and Burney’s Juliet,” Lorrie Clark on “Giving Mr. Rushworth a Brain: Austen Re-Minds Modernity,” Peter Graham on “‘Every generation has its improvements’: The Aesthetics and Ethics of Domestic Space,” Natasha and Frederick Duquette on “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers,” and Marcia Folsom, who introduced the new MLA volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park.

I’m very excited about this new book (and not just because it includes my essay on Mansfield Park and tragedy).

The food at the banquet (including an apricot tart for dessert, because “a good apricot is eatable”) was excellent and it was a delight, as always, to see people in period costume at the Regency Ball.

St George’s Anglican Church

Many of us went to Morning Prayer at St. George’s Anglican Church on Sunday morning (“A whole family assembling regularly for the purpose of prayer is fine!”), which was followed by brunch and a very entertaining talk on the Georgian Royal Navy by Patrick Stokes, former Chairman of the Jane Austen Society (UK) and a direct descendant of Jane Austen’s “own particular little brother,” Rear-Admiral Charles Austen.

Patrick Stokes

“A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” the play by Diana Birchall and Syrie James, was hilarious, and included not one but two surprise appearances at the end – the first by Bill James as Sir Thomas Bertram, and the second by Patrick Stokes as the Prince Regent. In her role as Mrs. Norris, Diana not only brought out the infamous green baize fabric, but also wore it, complete with a curtain rod.

The cast of “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park.” Thanks to Erna Arnesen and Diana Birchall for the photo.

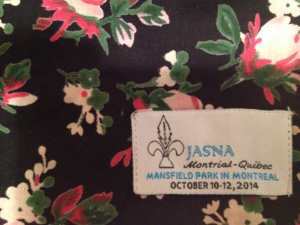

I’m very grateful to Elaine Bander and her team for welcoming us to Montreal to celebrate Jane Austen and Mansfield Park. It was a wonderful weekend of good company and a great deal of conversation. I love that the beautiful tote bags for this AGM were handmade in India by women whose work is supported by April Cornell’s The Giving World Foundation.

The AGM tote bags came in a variety of cotton prints, and I was very pleased with mine.

And, after spending so much time inside at the conference hotel, I really enjoyed the chance to explore Montreal, especially the Botanical Garden and Mount Royal.

The Chinese Garden at the Montreal Botanical Garden

I’m glad that the celebrations of two hundred years of Mansfield Park aren’t over quite yet, and that I can look forward to reading several more contributions to my blog post series “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” this fall. (Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret Horwitz – tomorrow – and by Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, Syrie James, John Baxter, Sharon Hamilton, Sara Malton, and many more. Please do subscribe to the blog, if you haven’t already, so you don’t miss any of their posts.)

I’m going to keep listening to Juliet Stevenson reading Mansfield Park over the coming weeks, too – listening to audiobooks always helps me slow down and attend to the details of Austen’s language. I’m also keen to read conference papers from this year’s AGM when they’re published in Persuasions and Persuasions On-Line.

The Olympic Park Tower

And there are future AGMs to look forward to: “Living in Jane Austen’s World” in Louisville, Kentucky, with Inger Brodey, Rachel M. Brownstein, and Amanda Vickery as plenary speakers (October 9-11, 2015), and “Emma at 200: ‘No One But Herself’” in Washington, DC (October 21-23, 2016). Thanks, JASNA. It’s a pleasure to listen to, and participate in, conversations about Jane Austen.

October 10, 2014

Fanny Price’s Prayers

Twenty-third in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Today is the first official day of the JASNA AGM in Montreal, where seven hundred of us are gathering to discuss and celebrate Mansfield Park. This weekend I get to have the pleasure of introducing Natasha Duquette and her work on Austen on two occasions. Tomorrow I’m introducing the AGM breakout session she and her husband Frederick Duquette are presenting on “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers,” and right now I get to introduce her guest post on Fanny’s “fervent prayers.”

Natasha and I attended the University of Alberta as undergraduates at the same time, but somehow we didn’t meet until several years later (at a conference in London, Ontario, even though – as we recently figured out – we took the same Chaucer class together at the U of A). It’s been a delight to reconnect with her and to discuss Mansfield Park.

Natasha and I attended the University of Alberta as undergraduates at the same time, but somehow we didn’t meet until several years later (at a conference in London, Ontario, even though – as we recently figured out – we took the same Chaucer class together at the U of A). It’s been a delight to reconnect with her and to discuss Mansfield Park.

Natasha is Associate Dean at Tyndale University College in Toronto, Ontario, where she also teaches in the Philosophy and English departments. Her research on Jane Austen has appeared in Jane Austen Sings the Blues (University of Alberta Press, 2009), Persuasions On-Line, and English Studies in Canada, and she co-edited – with Elisabeth Lenckos, whose guest post on Mansfield Park will appear in this series in December – Jane Austen and the Arts: Elegance, Propriety, and Harmony (Lehigh University Press, 2013). Natasha’s monograph Veiled Intent: Dissenting Women’s Theological Aesthetics is forthcoming with Pickwick.

He would marry Miss Crawford. It was a stab, in spite of every longstanding expectation; and she was obliged to repeat again and again that she was one of his dearest, before the words gave her any sensation. Could she believe Miss Crawford to deserve him, it would be – Oh, how different it would be – how far more tolerable! But he was deceived in her: he gave her merits which she had not; her faults were what they had ever been, but he saw them no longer. Till she had shed many tears over this deception, Fanny could not subdue her agitation; and the dejection which followed could only be relieved by fervent prayers for his happiness.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 27 (Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2003)

Fanny Price is the only heroine who Jane Austen depicts in an act of private prayer. This small window into Fanny’s spiritual life is in accord with Austen’s general depiction of her as a contemplative. In her excellent study Jane Austen’s Philosophy of the Virtues (Palgrave, 2005), Sarah Emsley presents Fanny as a deep thinker engaged in “philosophical contemplation” (108), and I have argued Fanny’s observation of the starry sky over dark woods is a moment of contemplative sublimity (“Sublime Repose”: The Spiritual Aesthetics of Landscape in Austen” in Jane Austen Sings the Blues, 2009).

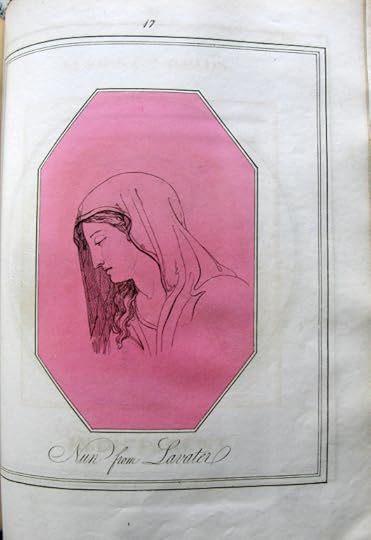

Like contemplative women through history – such as scientist and theologian Hildegaard of Bingen and phenomenologist Edith Stein – Fanny Price blends intellectual, philosophical, and spiritual contemplation in her figurative convent cell, the East Room of Mansfield Park. But unlike the idealized sisters of Williams Wordsworth’s sonnet “Nuns Fret Not,” the very human Fanny does balk at the limitations of a solitary, celibate future.

“Nun from Lavater,” an illustration in Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck’s Theory on the Classification of Beauty and Deformity (London: John & Arthur Arch, 1815). Thanks to Chawton House Librarian Charlotte Falconer for capturing this image.

Edmund Bertram’s apparent choice of Mary Crawford frustrates Fanny, and in response, she redirects her passion in spontaneous, almost Psalmic, cries of the heart. Like the biblical psalmist, Fanny wonders at the “prosperity of the wicked” (Psalm 73.3, KJV), and her fervent prayers are anguished and ardent petitions. Within the narrative framework of Mansfield Park, Fanny cannot initially accept the reality of Edmund’s attraction to Mary, despite the evidence she sees.

However, when Edmund tells Fanny that she and Mary are his “dearest objects,” Fanny quickly jumps to the conclusion that Edmund will wed Mary. Edmund’s statement breaks through any remaining layers of denial in her consciousness, and Fanny experiences harsh reality physically – “it was a stab.” Austen avoids simile and uses a powerful direct metaphor. It is not as if Fanny has been stabbed. She was stabbed. She feels it acutely. Stages of grief appear in rapid succession: shocked numbness marked by absence of “any sensation,” outrage emphasized with an exclamation mark, bafflement, weeping, and finally “dejection.” Paradoxically, this final stage functions as a turning point for Fanny, a pivot upwards towards faith and hope for “happiness” (Edmund’s, at least, if not her own). Fanny’s Psalmic descent will turn out to be a felix culpa or “happy fall.” It is a journey into the darkest aspects of her self – envy, judgment, rage, & doubt – with a redemptive twist at the end.

Upon re-visiting Mansfield Park for a second or third time, the reader may bring dramatic irony to Fanny’s impassioned prayers. They have a comic aspect in their very fervency. Fanny is far from perfect herself and very much a character in process of dynamic development. Her interpretation of Edmund’s statement as definitely indicating “he would marry Miss Crawford” is lacking in epistemological humility. Fanny is not omniscient, nor is the narrator, and her fatalistic, certain prediction of Edmund’s matrimonial future appears in a moment of free indirect discourse. Thankfully, the narrator is unreliable and fallible, the future is still open, and Fanny’s prayers will be answered in ways beyond anything she could ask or imagine.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, Joyce Tarpley, and Syrie James.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 7, 2014

The Scene-Painter, Part Two

As I promised in yesterday’s blog post, “Mansfield Park in Montreal,” I’m posting the second part of Diana Birchall’s “The Scene-Painter,” in which she imagines the details of the story that lies behind Jane Austen’s brief reference in Chapter 20 of Mansfield Park to the man who leaves the house having “spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied.” You can find Part One of “The Scene-Painter” here.

And if you’re going to be in Montreal this weekend for the JASNA AGM, you’ll be able to see another of Diana’s explorations of what’s “behind the scenes” at Mansfield Park, if you come to the play she and Syrie James co-wrote and are co-producing, “A Dangerous Intimacy.”

It did not appear, in succeeding days, that Edmund had influenced Tom in the slightest. The scene-painter spent hours in his chamber, and as Edmund had prophesied, it became a place where the maids and men of the house congregated, joined at all hours by Tom and Yates. Drinking went on and laughter was heard late at night, much to Fanny’s alarm, but as her cousin Tom was at the center of the revelry, she would not be afraid for her own safety, and did not like to speak of the matter. She was aware that any complaint would bring the wrath of Edmund, and she shrank from being the occasion for any high words between the brothers.

Sometimes the doings in Sharp’s rooms went on very late indeed, and then he slept much of the next day, so that the painting was going on very slowly. Perhaps, as he was being paid by the day, that was his intent; but it was the only aspect of the scene-painter’s residence that at all troubled Tom.

“If we don’t get forwarder with the scenes, our theater never will be complete,” he fretted. “Can’t you hurry it up a bit, Sharp?”

“Oh, art takes time to develop,” he said easily. “Never you fear, Tom, we will have a brilliant production. We cannot fail.”

Sharp was, like Tom, a talker, but his topics ranged farther than Tom’s usual gossip about people in town and the horses he was racing. Sharp professed to be interested in ideas, and finding a receptive audience among the maids and men, he was soon lecturing Sarah and Ellen, as well as the three young menservants who were moths to his candle, and loved to hear about the revolutionary new social currents and their spread in enlightened London circles.

“Only think, the shops and the picture-galleries, and going to the theatre every day. How grand London must be!” exclaimed Sarah, a fair-haired eighteen-year-old with round cheeks.

“And all the fine talking, the salons and coffee-houses Mr. Sharp speaks of. Oh, how I do long to see it all!” sighed pretty Ellen, her bright brown eyes aglow.

“Oh, quite. You must go there. It is only in these slow country places that people are so hidebound and old-fashioned. Quite intolerable. Buried here, you have no idea what freedom really is.”

“But if things are so very free, don’t the girls get into – trouble, Mr. Sharp?” Ellen asked hesitatingly.

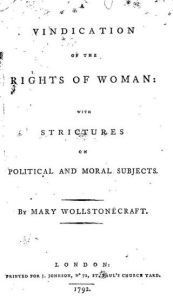

“To be sure they do, sometimes, but that happens everywhere, in the country as well as the city, and thinking people don’t pay any heed. They know that women have as good minds, and capacities, as men, and ought not to be only mothers, but valued for their work. Have you never read Mary Wollstonecraft, Ellen?”

“No; who is she?”

“Why, she is one of the finest women writers and thinkers that ever lived. Wrote a book called A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, and you ought to read it, and learn all about your natural rights. Every woman should. She didn’t bother with marriage, when having her children, I can tell you, but thought and acted like a man.”

“What happened to her, Mr. Sharp?” Ellen asked breathlessly.

“Well, she did marry in the end, to Godwin, the enlightened philosopher. Perhaps you have heard of him? No? – and then, well, she died,” he said. “But surely you girls don’t want to be kept down, in service. In the city, you can always find something to do, and a clever woman can make or marry a fortune.”

“What about men?” asked Rufus, the second footman, a strapping young fellow who spent his days arranging Lady Bertram’s shawls and walking her Pug. “I have sometimes thought I might do better in London, than in service.”

“No doubt of that,” Sharp assured him, “there are so many more chances in town. And after all, man, service is degrading! There’s no reason at all, you know, why one set of people should be masters, and others slaves.”

“Slaves!” exclaimed Tom jovially. “We pay all our people very well, I’ll have you know, Sharp.”

The men fell silent, but Sarah said thoughtfully, “But Mr. Sharp, isn’t it in the Bible, that we are to be content, in whatever state of life we have been called?”

“My dear Sarah, we are living in the nineteenth century,” he said kindly. “There has been a revolution in America, and in France. All men are created equal, you know. Have you not read Tom Paine and his Rights of Man? It is the right of every man, and woman too, to seek happiness, and do the best for himself he possibly can, without knocking under to other people.”

“That sounds fine to me,” said Samuel, the boot-blacking boy, his eyes glowing. “Do you think I might get a job in the theatre in London, and be an actor?”

“Why not? You’re a good-looking lad, and you are welcome to stay in my quarters whenever you do make your way to London.”

“See here, Tom, he’s going to have all your servants departing your employ at once,” laughed Yates.

Tom scoffed at that. “Phoo, phoo. Our people know when they’re well off. We don’t oppress any body at Mansfield Park, I can tell you, Sharp.”

“No, of course not. But servants are not always so fortunate in their masters as yours are. When you consider political justice, Bertram, you must admit that aristocratic privilege is a pernicious thing.”

“I agree that society must be changed,” drawled Yates, “certain sure. Nobody ever has enough money, that I can see. I know I have not.”

“If we don’t change our institutions voluntarily, they must be completely overthrown. Peaceably, of course; there’s no need for a Reign of Terror as there was in France. We are not that sort of a people, here in England. We are rational, and can see the merits of equality without violence.”

“I see the merits in a drink,” said Tom, “here, open another bottle of port, will you, Atkins,” he addressed the second coachman, who had been drinking in Sharp’s words eagerly.

Ellen had been following another line of thought. “What did you say that lady’s name was – how did she take care of her natural children, then? How did she live?”

“Mary Wollstonecraft? Oh, she was a governess or something of the sort, and lived with several gentlemen before marrying Godwin. She was none the worse for all that, and she was very well respected, because of being so clever. There’s nothing shameful in having a lover or two, you know. People of sense don’t think any thing of it, nowadays.”

“But the children,” murmured Ellen, blushing.

“The sins of the father, or mother for that matter, aren’t the fault of the sons,” said Tom airily.

“But see here, bastards are still disgraced in society, you know they are,” protested Yates.

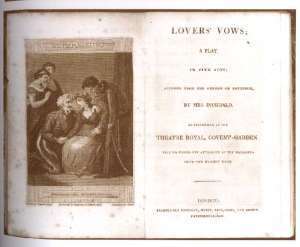

“Not so much, any more. Look at Agatha in our play, isn’t she a heroine despite having a natural son?”

“I would not wish the life of Agatha on any young woman!” protested Rufus the footman, “from what I have seen of the play.”

“Perhaps not; but the real point is, that you have seen the play. It has been shown dozens of times. The subject of love without marriage, and of natural children, is growing everywhere more acceptable. And at any rate, one does not have to have children. There are ways to prevent….”

He looked down at Ellen, and she moved closer to him. “Are there, Mr. Sharp?”

Samuel was thinking hard. “I vow, I will start saving my pay at once, and hope to go to London one day, and go on the stage,” he declared, with a glance at Tom. But Tom was playing with Sarah’s hair, and not listening.

“All this talk is making me tired. Another drink, Sharp?” asked Yates, and passed the port.

Fanny lay awake long that night, trying not to heed the sounds coming from next door. They were such as she had never heard before, and filled her with the utmost horror and shame. She tried to decide what she must do in the morning; there was only Edmund to consult, but she knew she could not speak to him on such a subject, for the world. It might, however, be possible to make some slight hint, and for many hours Fanny feverishly turned over, in her agitated mind, what she must say. Dawn found her still awake, though the sounds through the wall had diminished to heavy snores. Trembling with agitation and sleeplessness, she dressed herself, and went down stairs.

Fanny might bravely resolve to speak to Edmund, come what might, but opportunity was lacking. There was to be a rehearsal of the first three acts entire. To her misery about the shameful revelry she had heard in the night, was added her pain at being forced to see Edmund and Mary Crawford acting together for the first time, and rehearsing a scene of love. At mid-morning she was able to get away from her aunts, and she sought her refuge in the East Room. Unluckily, peace was not to be hers. First Miss Crawford, and then Edmund himself, came to her sanctum for purposes of rehearsing, an exercise that was nothing but torment to Fanny; and then after dinner there was the much-dreaded rehearsal.

Her cousins had been importuning her to read the part of Cottager’s wife, in the absence of Mrs. Grant, and Fanny was, with the greatest reluctance, ceasing to demur, almost more from sheer exhaustion than any thing else; when Julia entered the theatre all in affright, and announced that her father had come.

“My father is come!” Illustration by Hugh Thomson.

It could not have been at a worse moment. Henry Crawford was holding Maria’s hand, and Sharp, who had got oiled paints on the floor, was unsuccessfully trying to wipe up the mess with sponges provided by Atkins the under coachman, who was badly hung over.

Mrs. Norris, with great presence of mind, whisked Mr. Rushworth’s pink satin cloak away.

“Damn it all. We must get rid of these filthy sponges,” exclaimed Sharp.

“But what will we do about the floor, sir? That parquet is ruined.”

“Ellen, throw me that piece of green baize, will you? We can toss it over the spill.”

“It belongs to Mrs. Norris, sir, I don’t think she would like – .”

“Bother the old lady. Look here, Ellen, I suspect this job is up. Did you really mean that about wanting to come to London?”

“I did, that is, if you – .” She stopped.

“Of course, of course. So, if you ever get there, just make your way to Covent Garden and anybody can tell you my direction, will you do that?”

“Oh, yes, sir,” she breathed.

The young coachman carried off the sponges, and the company scattered, some to welcome Sir Thomas, others to leave the family to itself at this important moment. Only Yates continued rehearsing, oblivious to any impending unpleasantness.

Who can be in doubt as to what followed? When he heard the whole story of the theatre, Sir Thomas’s anger and disapprobation were very great. He said enough to make his displeasure felt, and then went about, destroying every trace of the theatre, and restoring his house to what it used to be, and ought to be.

Active and methodical, he had not only done all this before he resumed his seat as master of the house at dinner, he had also set the carpenter to work in pulling down what had been so lately put up in the billiard room, and given the scene painter his dismissal, long enough to justify the pleasing belief of his being then at least as far off as Northampton. The scene-painter was gone, having spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, and Joyce Tarpley.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

October 6, 2014

Mansfield Park in Montreal!

There are so many reasons to be excited about this year’s JASNA AGM. It focuses on Mansfield Park, which is a brilliant book, it’s in Montreal, which is a fabulous city, and, like all JASNA AGMs, it’s an opportunity to analyze and celebrate Austen’s writing with a wonderful group of very smart people.

Several of the contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” will be speaking at the AGM this weekend, including Juliet McMaster, Lynn Festa, Lorrie Clark, and Kathryn Davis (whose guest posts you can find listed here), Natasha Duquette (whose guest post will be published this Friday, October 10th), and Elisabeth Lenckos, Theresa Kenney, Sheryl Craig, and Sheila Johnson Kindred (whose guest posts will appear on the blog over the next few months). Sheila and I are presenting together on Saturday – our talk is called “Among the Proto-Janeites: Reading Mansfield Park for Consolation in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1815.” Several other contributors are attending the AGM, too: Deborah Barnum, Karen Doornebos, Margaret Horwitz, Hugh Kindred, Cheryl Kinney, Amy Patterson, Julie Strong, Margaret C. Sullivan, Deborah Yaffe, and, of course, Elaine Bander, AGM Coordinator. (I hope I haven’t missed anyone – please let me know if I have.)

I’m delighted that I get to introduce Marcia McClintock Folsom’s talk on “Teaching Mansfield Park in the Twenty-First Century: New Contexts, Controversies, and Opportunities,” in which she’ll tell us about the brand new MLA volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park. (You can read about my contribution to the volume here.) And I’m delighted to be introducing the breakout session Natasha and her husband, Frederick Duquette, are doing on Saturday afternoon: “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers.” The details about the schedule are on the AGM website. It’s going to be a busy weekend, and I’ve mentioned only a few of the highlights here.

I’m delighted that I get to introduce Marcia McClintock Folsom’s talk on “Teaching Mansfield Park in the Twenty-First Century: New Contexts, Controversies, and Opportunities,” in which she’ll tell us about the brand new MLA volume Approaches to Teaching Austen’s Mansfield Park. (You can read about my contribution to the volume here.) And I’m delighted to be introducing the breakout session Natasha and her husband, Frederick Duquette, are doing on Saturday afternoon: “Fanny Price Amidst the Philosophers.” The details about the schedule are on the AGM website. It’s going to be a busy weekend, and I’ve mentioned only a few of the highlights here.

I want to tell you a little bit more about one of the exciting special events at the AGM. Diana Birchall and Syrie James, who are both contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” have written a play called “A Dangerous Intimacy: Behind the Scenes at Mansfield Park,” which will be performed on Friday evening. Tickets are still available.

This is the second staged reading Diana and Syrie have collaborated on for a JASNA AGM – the first was the popular “Austen Assizes,” which was performed at the 2012 AGM in New York City. You can read more about the “Austen Assizes” and watch some of the highlights on Syrie’s website. Diana tells me the cast for “A Dangerous Intimacy” consists of “prominent Janeites with a turn for acting,” and Syrie promises the play will be very funny.

The cast of the “Austen Assizes” play. Thanks to Diana for the photo.

If you’ve been following “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” for a while, you’ll remember Diana’s guest post, the beginning of a short story called “The Scene-Painter,” and if you want to find out what happens next, you’ll want to read tomorrow’s blog post, which is Part Two of the story. Diana expands on the brief references Austen makes to the minor character who comes to Mansfield Park to paint scenes for the performance of Lovers’ Vows, and leaves having “spoilt only the floor of one room, ruined all the coachman’s sponges, and made five of the under-servants idle and dissatisfied” (Chapter 20). You can read (or reread) Part One here. Stay tuned for Part Two!

I know many of you who’ve been reading and commenting on these guest posts will be in Montreal for the AGM, too, and I’m looking forward to seeing you soon! Please come and talk to me at our breakout session or the authors’ signing event, or any time over the weekend. My secret plot to make the Mansfield Park celebrations extend well beyond the October long weekend is working, thanks to all of you, and I’m glad we get to continue the party even after the AGM ends on Sunday.

I’m also glad that the blog makes it possible for those of you who aren’t going to Montreal to participate in some of the celebrations of this amazing novel. Thank you for reading, for commenting, for sharing these posts with your friends, and for accepting the invitation to what is definitely the biggest – and longest-running – party I have ever hosted in my life.

October 3, 2014

How should we read the character of William Price?

Twenty-second in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Hugh Kindred is Emeritus Professor of Law at Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia, with special interests in international and maritime law. He has also conducted research on the naval career of Captain Charles Austen in Canada, Bermuda, and the United Kingdom. He’s a regular participant in JASNA Nova Scotia Regional meetings and he frequently attends the Jane Austen Society (UK) annual meetings at Chawton House and meetings of the JAS Kent Branch.

When our JASNA Nova Scotia group meets each December to celebrate Jane Austen’s birthday, it is Hugh who regularly proposes an eloquent birthday toast, which is always accompanied by a brief reading from Austen’s novels or letters. At the 2012 JASNA AGM in New York, Hugh and his wife Sheila Johnson Kindred presented a fascinating breakout session on “Naval Prize, Power, and Passion in Persuasion.” Today, it’s my pleasure to introduce his guest post on the character of William Price.

In this image from Master & Commander, you can clearly see the midshipmen’s uniforms.

William had obtained a ten days’ leave of absence to be given to Northamptonshire, and was coming, the happiest of lieutenants, because the latest made, to shew his happiness and describe his uniform.

He came; and he would have been delighted to shew his uniform there too, had not cruel custom prohibited its appearance except on duty. So the uniform remained at Portsmouth, and Edmund conjectured that before Fanny had any chance of seeing it, all its own freshness and all the freshness of its wearer’s feelings, must be worn away. It would be sunk into a badge of disgrace; for what can be more unbecoming, or more worthless, than the uniform of a lieutenant, who has been a lieutenant a year or two, and sees others made commanders before him? So reasoned Edmund, till his father made him the confidant of a scheme … .

This scheme was that [Fanny] should accompany her brother back to Portsmouth, and spend a little time with her own family. … Edmund considered it every way, and saw nothing but what was right … [and] good in itself … . This was enough to determine Sir Thomas; … [yet] his prime motive in sending her away, had very little to do with the propriety of her seeing her parents again, and nothing at all with any idea of making her happy. He certainly wished her to go willingly, but he as certainly wished her to be heartily sick of home before her visit ended; and that a little abstinence from the elegancies and luxuries of Mansfield Park would bring her mind into a sober state, and incline her to a juster estimate of the value of that home of greater permanence, and equal comfort, of which she had the offer.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 25 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

Joseph Morgan as William Price in the 2007 adaptation of Mansfield Park, directed by Iain B. MacDonald.

William Price is only a minor character in Mansfield Park, yet he is a significant one. Of the several places that he crops up in the novel, I have chosen this passage because it points to the most obvious of several ways to think about his role in Jane Austen’s creation. Why Austen formed him as she did is all speculation, of course, but Austen wrote with such care, finesse and deliberation that, even as I wonder at her prose, I constantly find myself wondering about the larger implications which lie beneath the surface of her stories.

So how should we read the character of William Price in Mansfield Park? First and foremost, he is a useful creation to advance the novel’s plot. Sir Thomas, in presenting his scheme in the passage above, rightly anticipates that Fanny will jump at the chance to travel with William to Portsmouth to see him dressed as a freshly minted lieutenant and to see him off to sea as an officer on HMS Thrush. Perhaps William’s part is not absolutely necessary, for Fanny might well have seized the opportunity to visit her family and her old home whether William was present or absent. But William’s presence makes Sir Thomas’ offer to Fanny that much more certain of acceptance as well as capable of execution. The latter consideration would have been important because Fanny could not have travelled to London and thence to Portsmouth except in the company of a suitable male, which William’s presence supplies.

Cartoon of midshipman supervising the daily slops.

It is made clear, of course, pace Edmund’s innocent approval, that Sir Thomas’ generosity is not altruistic. He wants Fanny to experience what he correctly supposes will be the relative misery of her family home in comparison with the civility and well-being of her adopted home at Mansfield Park and thus to appreciate fully the opportunity before her of attaining her own home of equal comfort by reversing her obstinate rejection of Henry Crawford’s offer of marriage. He wants her, in short, to make this visit in order to come to her senses, as he projects them. William is the very convenient yet unknowing agent of this scheme.

It is not clear whether Sir Thomas has anything to do with Henry Crawford’s subsequent arrival in Portsmouth to importune Fanny. His “dignified musings” are not said to have included any intention of reporting Fanny’s presence in Portsmouth to Crawford, who, in any case, could readily have been informed by others at Mansfield Park. Absent any evidence, Sir Thomas cannot be accused of the further infamy of deliberately putting Fanny in the way of Crawford in even more traumatic circumstances for her than at Mansfield Park. In this passage Sir Thomas appears controlling but well-meaning, by his lights, and not callous. And, though the scheme does not work out as Sir Thomas, at the time, desired, it serves Jane Austen very well to move her story forward.

A second way to consider how William Price appears in the novel involves the personal attributes that Austen ascribes to him. Compared to all the “gentlemen” at Mansfield Park, who are all tarnished products to varying degrees, though they are supposed by their breeding to know and do better, William Price is the only unblemished male. He is young and so has had less time than the others to learn or practise errant ways, but I also suggest that the personality and character given to him by Austen might be regarded as a standard of the ideal male in development, against which we readers may compare all the rest of them.

“William was often called on by his uncle to be the talker.” Illustration by C.E. Brock.

The novel’s narrator appears to imply approvingly that William Price is a young man who is going about life the right way to make something of himself, despite his lowly starting place, and doing it with a cheerful spirit and an open heart. Jane Austen seems to suggest there is virtue in hard work and endurance in the face of difficulties and hardship, for which there should be recognition and reward by society as readily as their attainment by idle inheritance. At the same time, she intimates that work and struggle are not by themselves sufficient without opportunity for education and refinement of mind and conduct, of the kind that Mansfield Park can offer.

There is ambivalence in these sentiments. The real world when Jane Austen was writing Mansfield Park was changing very rapidly, as she knew. The slave trade had been outlawed in England and the returns from slave based sugar plantations in the Americas, which were sources of sustenance for estates like Mansfield Park, were beginning to decline. (See the seventeenth post in this series, by Deborah Barnum – “Jane Austen’s ‘dead silence,’ or, How Guilty is Sir Thomas Bertram?” – and the ensuing online discussion.) The Napoleonic wars by sea and by land threatened the whole population and imposed an enormous economic and social burden on the country. A new cash-based economy centred on the cities and towns was challenging the ancient rural values of landed estates and family settlements. In this larger context, William Price may, perhaps, be viewed as the hopeful new man for the new conditions, even as Jane Austen approves the civility of the passing era of Mansfield Park.

“Complete in his lieutenant’s uniform.” Illustration by H.M. Brock

But will William Price succeed, as he deserves to? Here is a possible third consideration in thinking about Austen’s construction of this character. Being an efficient and effective midshipman or an outstanding leader as a lieutenant, and thus deserving to be “made up” to higher rank and income, may not have been enough for advancement. Promotion depended partly and inevitably on the varying national need for warships and officers, which was diminished after Nelson won the battle of Trafalgar in 1805 and British ascendancy over the seas was assured. It was also significantly influenced by a system of patronage, which was jealously controlled and applied by the upper classes. Jane Austen knew all about this system too, as she lets her characters tell us most directly.

First, Midshipman Price himself speaks despondently of ever becoming a Lieutenant: “I begin to think I shall never be a lieutenant, Fanny. Everybody gets made but me” (Chapter 25). William does become a lieutenant, to his great satisfaction and the delight and pride of Fanny, but only through the intervention of Henry Crawford. Hoping to advance himself in Fanny’s affections, Crawford applies to his uncle, who happens to be an Admiral, and persuades him to exercise his influence within the Admiralty. William benefits from this act of patronage by being appointed second lieutenant on HMS Thrush.

“Looked at him for a moment in speechless admiration.” Fanny sees William dressed as a Lieutenant just before he leaves the Price home to board his ship. Illustration by C.E. Brock.

Will Lieutenant Price rise further? Certainly not at the bidding of Crawford: his intervention was a once-only act of patronage out of his own selfish objectives, not a deed of generosity for the advancement of a young man of whom he cared or approved. Edmund shows that he understands the situation when he makes the second despondent comment about William’s future. In the second paragraph quoted at the head of this post, Edmund foretells that William’s prized new uniform as a lieutenant will, in a year or two, become a “badge of disgrace” as he sees others promoted to commanders before him.

Jane Austen clearly understood the chequered chances for advancement of a naval career by an aspiring and estimable candidate who was but a poor cousin of the upper class. But is she accepting of the part played by patronage or is she espousing the claims of merit in the way she presents the character of William Price in Mansfield Park? It is intriguing to think about William Price as the new man of the age who should rise more by ability than entitlement. We will never know whether Jane Austen had any such views in mind, and we are at liberty to read the character of William Price as we wish. But Jane Austen does give a possible hint of her opinions on the last page of the novel in making note, in passing, of “William’s continued good conduct, and rising fame” (Chapter 48).

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, Sarah Woodberry, and Joyce Tarpley.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 26, 2014

Discerning a Vocation in Mansfield Park – But Whose?

Twenty-first in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

The Rev. Dr. Maggie Arnold is currently serving as Assistant Rector at Grace Episcopal Church in Medford, Massachusetts. Many years ago, she and I read Pride and Prejudice together in a high school English class in our hometown, Halifax, Nova Scotia, and I’m very pleased to introduce her post on the important topic of “ordination” in Mansfield Park. I’m also grateful to her for the lovely illustration of a country house she contributed to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.”

Maggie holds degrees in Fine Arts from NSCAD University in Halifax and The University of the Arts in Philadelphia, a Master of Divinity from Boston University’s School of Theology, and a PhD in Religious and Theological Studies from Boston University. Her dissertation, “Mary Magdalene in the Era of Reformation,” compares Protestant and Catholic interpretations of the Magdalene in the Early Modern Period, especially as they related to the question of women’s public ministry.

“We shall be the losers,” continued Sir Thomas. “His going, though only eight miles, will be an unwelcome contraction of our family circle; but I should have been deeply mortified if any son of mine could reconcile himself to doing less. It is perfectly natural that you should not have thought much on the subject, Mr. Crawford. But a parish has wants and claims which can be known only by a clergyman constantly resident, and which no proxy can be capable of satisfying to the same extent. Edmund might, in the common phrase, do the duty of Thornton, that is, he might read prayers and preach, without giving up Mansfield Park; he might ride over every Sunday, to a house nominally inhabited, and go through divine service; he might be the clergyman of Thornton Lacey every seventh day, for three or four hours, if that would content him. But it will not. He knows that human nature needs more lessons than a weekly sermon can convey; and that if he does not live among his parishioners, and prove himself, by constant attention, their well-wisher and friend, he does very little either for their good or his own.”

“We shall be the losers,” continued Sir Thomas. “His going, though only eight miles, will be an unwelcome contraction of our family circle; but I should have been deeply mortified if any son of mine could reconcile himself to doing less. It is perfectly natural that you should not have thought much on the subject, Mr. Crawford. But a parish has wants and claims which can be known only by a clergyman constantly resident, and which no proxy can be capable of satisfying to the same extent. Edmund might, in the common phrase, do the duty of Thornton, that is, he might read prayers and preach, without giving up Mansfield Park; he might ride over every Sunday, to a house nominally inhabited, and go through divine service; he might be the clergyman of Thornton Lacey every seventh day, for three or four hours, if that would content him. But it will not. He knows that human nature needs more lessons than a weekly sermon can convey; and that if he does not live among his parishioners, and prove himself, by constant attention, their well-wisher and friend, he does very little either for their good or his own.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 25 (New York: Modern Library, 1933)

In re-reading Mansfield Park at a distance of some twenty years from my first acquaintance with the novel, I am now struck, as I was not then, by the repeated discussions of the role and nature of religion and the clergy. Edmund Bertram is to be ordained, and one strand of the story’s plot involves his working out of just what claims that profession will make upon him and how he will live up to them.

“Interior of a Church” (1819), by J.M.W. Turner

Early in the story, when the party from Mansfield Park visits Sotherton and sees the chapel, Fanny describes her image of a space for domestic piety: “melancholy” and “grand.” The topic of faith leads to Mary Crawford’s discovery that Edmund is himself to take orders, and to his defense of that vocation. In a later conversation with Mary Crawford, Dr. Grant, the holder of the Mansfield living, is revealed to be a bad clergyman because of his gluttony and selfish temperament.

Other posts in this series have explored some of these passages and what they may demonstrate about the values and virtues advanced by Austen. (See “Why Tom Bertram is right that Dr. Grant will ‘soon pop off,’” by Cheryl Kinney, “Something from Nothing,” by Mary Lu Roffey Redden, and “Dr. Grant’s Green Goose,” by Julie Strong.)

In my text, an exchange between Sir Thomas Bertram and Henry Crawford, Sir Thomas lays out his reasons for believing that a pastor ought to live within his parish. A good pastor must know the affairs of the community intimately, caring about them as his own, and he must provide a present example of Christian discipleship to his congregation.

Taken together, these discussions serve to show a sympathy of mind and spiritual commitment that unites Fanny and Edmund. This agreement makes their ultimate marriage the right one, after the mistaken attachment Edmund forms for the frivolous Mary Crawford, and the danger of Henry Crawford’s proposal to Fanny. Fanny and Edmund share a high ideal of the church’s place in society and of ordained vocations as a call to servant ministry. Many of the concerns the author gives to Edmund and Fanny would be animating principles of the Oxford Movement, which began less than twenty years after Mansfield Park’s publication. The Tractarians were likewise preoccupied with a reform and renewal of local parish life and with the spiritual formation of the clergy.

Of the young couple, however, it is Fanny more than Edmund who possesses the character of a Christ-like servant. She displays this character in her relations with family and friends, ministering patiently and with quiet humility in the household. Her nature does not permit her to forget even the needs of the officious and ungrateful Mrs. Norris, or the indolent and narcissistic Lady Bertram.

But beyond being an angel in the house, Fanny is also a more public apologist for Christianity. She is passionate and articulate in advocating a righteous church, joining heartily in theological discussions with Edmund and even initiating them, as in the conversation in the Sotherton chapel. Indeed, her description of the chapel she would rather have found there resembles an Oxford Movement church, with moody, neo-Gothic decorations and literary references. It is surely not insignificant that in her most visible moment before Mansfield society, at her coming-out ball, her only desired ornament is a cross.

But beyond being an angel in the house, Fanny is also a more public apologist for Christianity. She is passionate and articulate in advocating a righteous church, joining heartily in theological discussions with Edmund and even initiating them, as in the conversation in the Sotherton chapel. Indeed, her description of the chapel she would rather have found there resembles an Oxford Movement church, with moody, neo-Gothic decorations and literary references. It is surely not insignificant that in her most visible moment before Mansfield society, at her coming-out ball, her only desired ornament is a cross.

Fanny is finally able to fulfill her own religious vocation as the wife of a clergyman, a prominent role that had evolved in Protestant culture since the innovation of a married clergy in the Reformation. Pastors’ wives were models of faith as well as of its application in marriage, the raising of children, the running of the household, and charitable work in the parish. Though this was the happy ending of Mansfield Park’s early nineteenth-century context, among the tragic elements of the novel for twenty-first century readers must be the limitation placed on the career of a woman so faithful in her ministry to her neighbours and so eloquent in her vision of what the church could be.

Born two hundred years later, would Fanny have succeeded naturally to the living at Mansfield Park and overcome her shyness to preach redemption for latter-day Bertrams and Crawfords?

Katharine Jefferts Schori, Presiding Bishop of the E.C.U.S.A. (from The Grand Island Independent)

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Hugh Kindred, Natasha Duquette, Margaret Horwitz, and Syrie James.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 23, 2014

An Evening with Patrick Stokes in Halifax

Patrick Stokes, former Chairman of the Jane Austen Society (UK), will be visiting Halifax in the week before the JASNA AGM in Montreal. At the AGM, he’ll give a plenary lecture on October 12th on “‘Rears and Vices’: The Georgian Royal Navy.”

You’re invited to our next JASNA Nova Scotia meeting, in Halifax, on Tuesday, October 7th at 7:30 p.m. for an informal conversation with Patrick about the Royal Navy. Let me know if you’re interested, either by email (semsley at gmail dot com) or by leaving a comment here, and I’ll pass on details about the location.

What a wonderful time we had here in Halifax in September of 2005, when Patrick organized the JAS conference “Jane Austen and the North Atlantic.” Sheila Johnson Kindred gave a talk on “Charles and Francis Austen in Halifax, Canada,” Brian Southam spoke about fact and fiction in a lecture on “Jane Austen and North America,” Peter W. Graham analyzed “Insular Austen, Oceanic Austen: ‘Bits of Ivory’ and Beyond,” Brian Cuthbertson gave an overview of Halifax history, and I talked about Canadian and American readers of Austen’s happy endings.

What a wonderful time we had here in Halifax in September of 2005, when Patrick organized the JAS conference “Jane Austen and the North Atlantic.” Sheila Johnson Kindred gave a talk on “Charles and Francis Austen in Halifax, Canada,” Brian Southam spoke about fact and fiction in a lecture on “Jane Austen and North America,” Peter W. Graham analyzed “Insular Austen, Oceanic Austen: ‘Bits of Ivory’ and Beyond,” Brian Cuthbertson gave an overview of Halifax history, and I talked about Canadian and American readers of Austen’s happy endings.

We all enjoyed touring Uniacke House, the Maritime Command Museum, Government House, and other local highlights. At the time I was still teaching in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and it was a real pleasure to come home to Halifax to participate in such an inspiring conference.

You can read more about the conference in Jane Austen and the North Atlantic, the volume of essays I edited for the Jane Austen Society.

JASNA Nova Scotia members are very much looking forward to welcoming Patrick Stokes back to Halifax. Please join us on October 7th!

Uniacke House, Mount Uniacke, Nova Scotia

September 19, 2014

Mary Crawford: The Black Cloud of Mansfield Park

Twentieth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

One of the things I like best about hosting this party for Mansfield Park is that I can bring together so many of Jane Austen’s readers. Among the contributors to the series are writers of Austen-inspired fiction, bloggers, booksellers, journalists, librarians, and academics. There’s even one priest, one doctor, and one lawyer – let’s see what happens if the three of them walk into a bar at the JASNA AGM in Montreal next month. I like that there’s diversity even among those of us trained as academics – several study Austen and her contemporaries, of course, but there are also scholars of Early Modern literature and of Modernist literature. All of us share an interest in this complex and endlessly fascinating novel, and all of us are grateful to you for reading and participating in the conversations. It wouldn’t be much of a party without you!

It’s a pleasure today to introduce a guest post on Mary Crawford by Laurel Ann Nattress, who hosts the well-known blog Austenprose.com. I’ve followed Laurel Ann’s blog for a long time, and have also enjoyed writing reviews for Austenprose. Laurel Ann calls herself “a life-long acolyte of Jane Austen,” and says her blog is “devoted to the oeuvre of my favorite author and the many books and movies that she has inspired.” A Life Member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and a regular contributor to the Jane Austen Centre Online Magazine, Laurel Ann is also the editor of the very entertaining short story collection Jane Austen Made Me Do It (2011), which includes stories by Stephanie Barron, Carrie Bebris, Laurie Viera Rigler, and many others, including three writers who are also contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” – Diana Birchall, Syrie James, and Margaret C. Sullivan.

It’s a pleasure today to introduce a guest post on Mary Crawford by Laurel Ann Nattress, who hosts the well-known blog Austenprose.com. I’ve followed Laurel Ann’s blog for a long time, and have also enjoyed writing reviews for Austenprose. Laurel Ann calls herself “a life-long acolyte of Jane Austen,” and says her blog is “devoted to the oeuvre of my favorite author and the many books and movies that she has inspired.” A Life Member of the Jane Austen Society of North America and a regular contributor to the Jane Austen Centre Online Magazine, Laurel Ann is also the editor of the very entertaining short story collection Jane Austen Made Me Do It (2011), which includes stories by Stephanie Barron, Carrie Bebris, Laurie Viera Rigler, and many others, including three writers who are also contributors to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park” – Diana Birchall, Syrie James, and Margaret C. Sullivan.

Classically trained as a landscape designer at California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo, Laurel Ann has also worked in marketing for a Grand Opera company, and at present, she says, she “delights in introducing neophytes to the charms of Miss Austen’s prose as a bookseller at Barnes & Noble.” An expatriate of southern California, Laurel Ann lives in a country cottage near Snohomish, Washington where, she tells me, “it rains a lot.” (Sounds like Nova Scotia to me.) Visit Laurel Ann at her blog Austenprose – A Jane Austen Blog, on Twitter as @Austenprose, and on Facebook as Laurel Ann Nattress.

I was amazed and humbled when Sarah Emsley asked me to contribute a blog post for “An Invitation to Mansfield Park.” Not being a scholar of her caliber, or her readers, what could I possibly offer to this collection of essays? So, I take up this assignment, hat in hand, from the perspective of a Janeite, offering a reader’s opinion on my favorite line and chapter from Jane Austen’s most complex and thought-provoking novel.

I remember my first encounter with Mansfield Park. It was the third Austen novel I read after Pride and Prejudice and Emma. I had no idea what to expect, since this was 1986, long before I even knew there was a Jane Austen Society of North America and ten years before the creation of the Internet website The Republic of Pemberley to enlighten me on what was ahead. Looking back now, those were indeed the wilderness years when Jane Austen enthusiasts read and worshiped in silence.

My first impression of Mansfield Park was not what I expected. It was dark and brooding. The characters seemed to be at continual odds with each other. It was unsettling. Contemplative. Puzzling. It was not anything like the sparkling, witty and romantic Pride and Prejudice that she was so famous for. I was miserable, and totally engrossed at the same time — a Jane Austen bus accident that defied explanation. With no one to talk it over with, I read it again. Still puzzled, I put it aside. Ten years later, and then twenty, I read it again. It became my holy grail of literature. After years of Austen study, and with the benefit of discussing characters and plot points with other Janeites I had met on the Internet, Mansfield Park had evolved, for me, into the hardest-won literary battle of my life — the struggle had made the victory all the sweeter.

My first impression of Mansfield Park was not what I expected. It was dark and brooding. The characters seemed to be at continual odds with each other. It was unsettling. Contemplative. Puzzling. It was not anything like the sparkling, witty and romantic Pride and Prejudice that she was so famous for. I was miserable, and totally engrossed at the same time — a Jane Austen bus accident that defied explanation. With no one to talk it over with, I read it again. Still puzzled, I put it aside. Ten years later, and then twenty, I read it again. It became my holy grail of literature. After years of Austen study, and with the benefit of discussing characters and plot points with other Janeites I had met on the Internet, Mansfield Park had evolved, for me, into the hardest-won literary battle of my life — the struggle had made the victory all the sweeter.

During this thirty-year sojourn with Austen’s dark horse I connected with a particular chapter that was my ah-ha moment — that epiphany of illumination when I finally got it — or at least I thought so. Chapter 22 was my magic key. It revealed so much and answered many of my questions. Our heroine Fanny Price has been sent on an errand to the village by Mrs. Norris and been caught in a downpour without an umbrella. Huddled under a sparse oak tree outside of Mansfield parsonage, one of its residents Mary Crawford spies her shivering in the rain and sees an opportunity for her own entertainment, sending Dr. Grant out with an umbrella to fetch her inside. At this point, the sophisticated Miss Crawford is bored without the female companionship of the Bertram sisters and has cast her net for Fanny as her new friend. Mary and Mrs. Grant mollify Fanny’s objections to staying with dry clothes and attention. Mary plays the harp, entreating Fanny to stay longer than she wants:

“Another quarter of an hour,” said Miss Crawford, “and we shall see how [the weather] will be. Do not run away the first moment of its holding up. Those clouds look alarming.”

“But they are passed over,” said Fanny. — “I have been watching them. — This weather is all from the south.”

“South or north, I know a black cloud when I see it; and you must not set forward while it is so threatening. And besides, I want to play something more to you — a very pretty piece — and your cousin Edmund’s prime favourite. You must stay and hear your cousin’s favourite.”

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 22 (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1988)

“Dr Grant himself went out with an umbrella.” Illustration by H.M. Brock.

This short passage is so telling for me. Mary Crawford is bending Fanny’s will, as she does to so many in the novel. She speaks authoratively, decisively and officiously to Fanny, dismissing her observation of the rain having let up.

“South or north, I know a black cloud when I see it; and you must not set forward while it is so threatening.”

Like a spider to the fly, Mary has drawn poor Fanny into her web and made her stay longer than she wants to. When Fanny, the keen observer of nature, and the moral compass of the novel, expresses her opinion of the weather clearing as an exit cue to her hostess, she is dismissed by Miss Crawford, a character who reveals her controlling, selfish, and arrogant nature by stating that she knows a black cloud when she sees one, yet has not looked out the window. Screeching halt! Giant red flag! Austen has cleverly revealed that manipulative Mary and gentle Fanny are as opposite as black and white in their view of the world. Mary knows a black cloud when she sees one, because she is one. Her presence and opposing opinions will continue to dampen her encounters throughout the novel, and Fanny, who sees only the truth before her, will remain true to her own principles and our hearts.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park . Coming soon: guest posts by Maggie Arnold, Hugh Kindred, Natasha Duquette, and Margaret Horwitz.

Subscribe by email or follow the blog so you don’t miss these fabulous contributions to the Mansfield Park party! Or follow along by connecting with me on Facebook, Twitter (@Sarah_Emsley), or Pinterest.

September 12, 2014

Henry Crawford and Moral Taste

Nineteenth in a series of posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Elaine Bander was the first person I asked to contribute a guest post to this series celebrating Mansfield Park. Last fall, when JASNA Nova Scotia was fortunate to have Elaine visit us to give a talk on “Jane Austen’s Fanny Price and Lord Nelson: Rethinking the National Hero(ine),” I mentioned that I had been thinking about putting something together on my blog to honour Mansfield Park. At the time, I imagined inviting a few people to write guest posts, but the party kept getting bigger and I am so pleased to be celebrating with all of you. Thank you, Elaine, for being the first to sign on!

Elaine says she’s been pondering Mansfield Park since she began writing her dissertation on Austen nearly forty years ago. Now retired from teaching at Dawson College in Montreal, she is Coordinator of JASNA’s 2014 AGM: “Mansfield Park in Montréal: Contexts, Conventions & Controversies” (October 10-12, 2014) and serves on the editorial board of JASNA’s journal, Persuasions.

I interviewed her last fall about her experience in JASNA’s International Visitor Program, her longstanding connections with The Burney Society, and her experience of discovering Jane Austen’s novels. You can read the interview here, and you can read about Elaine’s visit to Halifax and her talk on Fanny Price’s courage here. I know the AGM is going to be wonderful and I can’t wait to spend the weekend talking about Mansfield Park in person with so many of you!

It was a picture which Henry Crawford had moral taste enough to value. Fanny’s attractions increased – increased two-fold – for the sensibility which beautified her complexion and illuminated her countenance, was an attraction in itself. He was no longer in doubt of the capabilities of her heart. She had feeling, genuine feeling. It would be something to be loved by such a girl, to excite the first ardours of her young, unsophisticated mind! She interested him more than he had foreseen. A fortnight was not enough. His stay became indefinite.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 24 (Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2006)

Henry Crawford, a disengaged, charming, compulsive flirt, begins to fall in love with Fanny Price when he perceives the warmth and depth of her feeling for her brother William. It helps that he’s bored, that Maria and Julia are gone, and that restless, gifted, undisciplined Henry, coming to the end of his duty visit to his sisters, is looking for a new project or challenge. His original “wicked project” (Mary’s words) was to make a small hole in Fanny’s heart, to woo her lightly for the sport of the hunt. Her obvious “sensibility,” however, intrigues and attracts him.

Taught by his uncle to despise marriage and to think all women venial, Henry imagines exciting “the first ardours of her young, unsophisticated mind!” He already perceives that Fanny is not like her cousins, and he will soon tell her that she has something of the angel about her. So Henry postpones his departure.

Neither a stock despoiler of virgins nor a Lovelace-like rake, Henry has “moral taste.” This expression has a history going back to the philosophical writings of Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury (1671-1713) and was current in the general popular culture of Austen’s time, underpinning much of the literature of sensibility and posing a philosophical opposition to more traditional morality (like Fanny’s) founded upon firm moral principles and the duty of reflection.

Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury

Meanwhile Fanny’s own aesthetic taste is powerfully attracted to Henry’s considerable acting talent, albeit without seriously affecting her moral judgment of him. During the rehearsals, she “believed herself to derive as much innocent enjoyment from the play as any of them; – Henry Crawford acted well, and it was a pleasure to her to creep into the theatre, and attend the rehearsal of the first act” of Lovers’ Vows.

When later Henry reads from King Henry VIII, Fanny responds involuntarily, against her conscious, rational judgment and will, against her very “principles,” to his acting skill: her needle falls from her hand, and “the eyes which had appeared so studiously to avoid him throughout the day, were turned and fixed on Crawford, fixed on him for minutes . . . until the book was closed, and the charm was broken.” With Henry’s charm broken, Fanny’s rational judgment reasserts itself. She resists equating aesthetic good with moral good.

Lovers’ Vows

Shaftesbury had claimed that just as we are naturally attracted to the beautiful, so too we have an innate sense or attraction to the good. Marianne Dashwood references a form of this belief when she defends her transgressive visit to Allenham with Willoughby: “for if there had been any real impropriety in what I did, I should have been sensible of it at the time, for we always know when we are acting wrong, and with such a conviction I could have had no pleasure.” After some reflection, Marianne admits, “Perhaps, Elinor, it was rather ill-judged in me to go to Allenham.”