Sarah Emsley's Blog, page 28

June 23, 2015

Birthday “Coincidences” in Emma and Anne of Green Gables

Harriet Smith is delighted by the idea that Robert Martin’s birthday is just two weeks and a day before her own. In Chapter 4 of Jane Austen’s Emma, she tells Emma that “He was four-and-twenty the 8th of last June, and my birth-day is the 23d – just a fortnight and a day’s difference! which is very odd!”

Emma was published on December 25, 1815, and I’m rereading it in honour of the 200th anniversary. Soon I’ll be able to tell you more about the exciting series of guest blog posts I’m planning – kind of like “An Invitation to Mansfield Park,” the series I hosted in 2014, but shorter. The new series will begin in December of this year.

For now, I want tell you about something that occurred to me when I read about the “coincidence” that both Harriet Smith and Robert Martin were born in June.

In Anne of Green Gables, when Anne Shirley meets Diana Barry for the first time, Marilla asks if she found Diana a “kindred spirit,” and Anne launches into a rapturous monologue about her new friend. Among the many delightful things she has discovered is the fact that “Diana’s birthday is in February and mine is in March. Don’t you think that is a very strange coincidence?”

So here’s my question for you – do you think L.M. Montgomery is consciously echoing Austen here? I love the idea that having birthdays in the same month, or in consecutive months, is a meaningful coincidence.

I visited Prince Edward Island again last week and I have some new photos to share with you. What a difference a few weeks can make! (Scroll down to the bottom of this post on “Anne and Gilbert After the Happy Ending” to see photos of snow and grey skies, from my visit at the end of April).

L.M. Montgomery’s birthplace, New London

In the distance you can just see the famous sand dunes of New London Bay.

Dalvay Beach

French River. One of the most photographed places in PEI.

Springbrook

Happy birthday to Harriet Smith today, and happy birthday to anyone else who happens to have a birthday in June (or May, or July, or February, or March).

June 12, 2015

Austen and Ambition

I went to Philadelphia last weekend to speak on Jane Austen and ambition at a JASNA Eastern Pennsylvania meeting, and my favourite part of the trip was the lively discussion after my talk about whether Austen saw ambition as a vice or a virtue. It was wonderful to discuss this controversial question with so many smart people who know Austen’s novels and letters so well.

The conversation inspired me to consider what I want to do next with this topic. Blog posts? A new essay on ambition, focusing on a specific novel? (Or perhaps, someday, a book on Austen and ambition?) I’ll have to spend some more time thinking about these questions. For now, if you’d like to know more about my talk, you might be interested in reading what Deborah Yaffe (author of Among the Janeites) wrote on her blog about the event: “Austen, ambition and Emsley.” It was such fun to see Deborah and other JASNA friends both old and new, and to explore this exciting topic with them.

Here are two of of my favourite passages about ambition in Austen’s novels:

Mrs. Dashwood and Edward Ferrars discuss ambition in Sense and Sensibility, Chapter 17:

“You have no ambition, I well know. Your wishes are all moderate.”

“As moderate as those of the rest of the world, I believe. I wish as well as every body else to be perfectly happy; but like every body else it must be in my own way. Greatness will not make me so.”

I love how Mrs. Dashwood tells, rather than asks, Edward about his ambition. She’s trying to reassure him it’s all right that he lacks professional ambition. But in fact he has very high ambitions of a different kind.

Lady Catherine to Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, Chapter 56:

“Do not imagine, Miss Bennet, that your ambition will ever be gratified.”

If Elizabeth had been ambitious about “marrying up,” she could have accepted Darcy’s first proposal.

And then in Austen’s letters, the best line about ambition is “I wore my Aunt’s gown & handkercheif, & my hair was at least tidy, which was all my ambition” (20 November 1800).

On my run on Sunday morning I stopped at Independence Hall to take a picture and to read about the Liberty Bell.

I had a fabulous weekend in Philadelphia and I’m grateful to Paul Savidge, Regional Coordinator, and members of the Board and Region for inviting me to visit. It was a weekend of good books and good conversations, and that made me very happy. (Good food, too….)

It was great to visit the Rodin Museum on Sunday.

May 15, 2015

Reading Austen’s Emma with Sherlock Holmes, Dr. Watson, and Deborah Knuth Klenck

I’m excited to share the news that Deborah Knuth Klenck is coming to Halifax later this month and she’ll speak on “Learning to Read with Emma” at a JASNA Nova Scotia event on Sunday, May 31st at 2pm. Please email me (semsley at gmail dot com) or leave a comment here if you’re interested in attending and I can send you more details.

The following weekend, I’ll be in Philadelphia to give a talk on “Austen and Ambition,” and I can’t wait to meet up with friends both old and new from JASNA’s Eastern Pennsylvania Region. The luncheon and talk will be held at the Sheraton Society Hill Hotel on Saturday, June 6th at 11:30am. Details and registration information are available here.

I’m having such fun writing about ambition in Austen’s life and works—and the fascinating question of whether ambition is a virtue or a vice—and it would be very easy for me to write several blog posts about this topic. But I’ll save that for another time, because right now I want to tell you about Deborah’s talk on Emma.

The talk she’s going to give in Halifax is a version of one she’ll give in June at the Jane Austen Summer Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She tells me “it’s about how much more we understand the novel as we re-re-read it. It’s the debut of my theory of reading based on the detective stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: first readers are clueless Watsons who think they’re Holmeses—Emma thinks she’s Holmes and takes a LONG time to see that she’s been Watson all along. Both authors mislead the reader the first time through, and the talk goes through some examples.” Deborah says, “I’ve probably read the novel thirty times or so, but I’m still ‘getting’ stuff I should have seen earlier.”

The talk she’s going to give in Halifax is a version of one she’ll give in June at the Jane Austen Summer Program at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She tells me “it’s about how much more we understand the novel as we re-re-read it. It’s the debut of my theory of reading based on the detective stories of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle: first readers are clueless Watsons who think they’re Holmeses—Emma thinks she’s Holmes and takes a LONG time to see that she’s been Watson all along. Both authors mislead the reader the first time through, and the talk goes through some examples.” Deborah says, “I’ve probably read the novel thirty times or so, but I’m still ‘getting’ stuff I should have seen earlier.”

Deborah was trained at Smith College and Yale University and is Professor of English at Colgate University, where she teaches classes on Shakespeare and Milton as well as on eighteenth-century writers and, of course, Jane Austen. She says her love of Austen was “of such long-standing unabashedness that, at first, it hardly seemed to be a sufficiently ‘academic’ field for research. Fortunately, between Colgate students clamoring for a Jane Austen course and the enthusiasm of J. David ‘Jack’ Grey, a co-founder of the Jane Austen Society of North America,” she says, she was encouraged to begin writing and teaching about Austen’s work.

Her first JASNA AGM talk was on female friendship in the Juvenilia, in Manhattan in 1987. She has since spoken at AGMs in Santa Fe, Lake Louise, Milwaukee, Philadelphia, and, she adds, “almost Minneapolis, where my son, an Austenite Ph.D. candidate in his own right, delivered my talk in my stead, after I broke my leg.” She has also been a guest speaker at many regional JASNA meetings. Deborah tells me she is delighted to have a chance to meet some of the members of JASNA Nova Scotia. I know we are equally delighted to have the opportunity to hear her speak.

Today, in anticipation of Deborah’s talk, I’m pleased to share with you a short piece she wrote introducing her idea about reading and rereading Emma with Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson.

I have taught British literature at Colgate University since 1978. I began with courses in the field of my graduate work: Restoration and eighteenth-century literature, predominantly satire. Over time, partly owing to student demand, I have taught more and more courses on fiction—and the shift in my teaching led to my writing on Jane Austen—now a much more important subject of my scholarship than the works of Pope, Swift, or Congreve. My Jane Austen seminar became a frequent offering. Nevertheless, I am always acutely aware that a fiction course presents a special challenge to undergraduate readers and hence to their professor: the problem? In contrast with a course where drama or poetry prevails, a fiction course is rather unforgiving: if one falls behind on the reading, how can one ever catch up with what rapidly becomes a runaway train?

It’s true that a senior seminar on Jane Austen requires a lot of reading, but many students who elect such a course are already familiar with (and love) at least some texts on the syllabus. The first time I taught English 388, Colgate’s “Survey of the British Novel,” on the other hand, I couldn’t count on well-prepared “fans” of the books. I tried to envision how I would “get” the class “through” the texts (one of which was Samuel Richardson’s Clarissa).

I explained my dilemma in a kind of cry for help on the first day of class. I passed out a famous 1912 photograph of Robert Falcon Scott and his four compatriots at the South Pole. I told the class the story of Scott’s doomed expedition, and pointed to the harnesses the men wear in the picture: they were hauling their own sledges, I explained. In contrast, Roald Amundsen, who beat the British to the Pole and brought his men back alive, used sled dogs on the journey. (The dogs were, of course, used in more ways than one: some became, as planned, a food source for men and dogs along the way and on the way back, but this was not the aspect of the contrast I wanted to emphasize.)

“Why did I show you this picture?” I asked the class. “Because when I was offered the opportunity to teach this course, I immediately conceived that getting through these novels in a single term would require that I pull you bodily through the texts.”

“I have a bad back,” I continued, “and therefore, in this course, you have to be the dogs.” (The point was about speed and economy of effort—not about any plans to experiment with recipes for cannibal stew. Luckily, the class seemed to appreciate the analogy in the way I meant it.)

By and large, such pep talks have worked, over the years.

But on the eve of the two-hundredth birthday of Charles Dickens, I undertook to revive a senior seminar on his work. The course had been taught by my late colleague, the novelist Frederick Busch, but had languished in the Catalogue since his death. My bold plan was in honor of Fred as much as Dickens, but it filled me with dread—how does one arrange a course in which there will be almost 4,000 pages of reading?

Having wrung all the significance I could out of the dog-sledding metaphor, I came up with another, almost contemporaneous British touchstone for reading: the “Sherlock Holmes method.”

The Arthur Conan Doyle short stories and novels are told to us by Dr. Watson, a rather clueless if amiable chap. But at the end of every adventure, Holmes reviews everything that has contributed to the solution of the mystery—clues and plot elements that he has understood from the start—finally letting Watson and the reader know what’s actually been going on. In the late spring before the fall seminar, I sent all the students pre-registered for the course (there were 17 of them) the full syllabus, including the titles and specific editions we were to use. I enjoined them to “pre-read” all of the novels—so that we could be re-reading them together throughout the fall. “On our first readings of a novel,” I explained—or perhaps warned, “we think we understand things—we like to fancy ourselves Holmes. But it often turns out that we’re more like Watson.” I hoped that our second readings during the fall term would be much more useful if everyone got the Watson work out of the way over the summer.

It worked! During the fall term, everyone found their way around the texts with the ease that comes with familiarity. Our class discussions were especially satisfying because everyone entered into them, at every class.

What happens when we apply Sherlock Holmes’s methods to another two-hundredth-birthday subject: Emma? What do we learn when we re-read Emma? And how long does it take Emma herself before she realizes that she’s been “reading” her own surroundings and neighbors as if she is a clueless Watson, not, as she assumes, a clever Holmes?

That’s the subject of my talk, originally titled “‘Elementary, my Dear Harriet?’: Misreadings and Missed Readings in Emma” and now titled, more simply, “Learning to Read with Emma.”

May 9, 2015

Rose Reads Mansfield Park

My fourteen-year-old friend Rose is reading Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park for the first time. Last fall she reviewed the Real Reads version of the novel adapted by Gill Tavner, and after she read your comments encouraging her to read the original—thank you, dear readers!—she decided to try it. In honour of the 201st anniversary of Mansfield Park, which was published on May 9, 1814, here is the first instalment of Rose’s commentary.

After reading the abridged version I was expecting most of the things I saw. One thing that did surprise me was Fanny. She is really relatable, which I didn’t find in the shorter version. She is sweet—probably funny when she knows you well and quiet when she doesn’t. As far as I know this might be one of Jane Austen’s more normal characters. Not everyone can be as sassy as Lizzy Bennet and I think I like that the books show that.

It’s way more apparent here how the adults think they are doing Fanny a favor and how wrong they really are. It also highlights how bad they are at communicating their feelings. Fanny is too scared to share how she feels about being away from home and the truly sad bit about this is that she has every right to be. Nobody is going to care if she complains. In fact they’ve said they will send her away or punish her if she isn’t happy. It’s so awful for them to force these expectations on her! In the abridged version of the book the author made her seem like a wimp. She just couldn’t manage a new environment or even adapt. That’s so wrong! She’s being bullied, shamed, and criticized, all while being as polite and cheerful as she can.

I find this book to be very similar to a lot of modern books about the new girl in school. Someone used to be the best student, tragedy strikes, she moves to a better school, her grades drop, she’s bullied…. She falls for the popular boy, the rival mean girl appears, the main character is good and sweet, she wins, she lives happily ever after…. Reading this book makes you realize how influential Jane Austen was.

The Fanny and Edmund thing can be a bit weird to read about, especially knowing the end. If a modern author were writing this it would turn out that there was some kind of scandal and they weren’t actually cousins. I would feel very safe supporting (read: adoring) that relationship if they weren’t blood relatives. But it seems as if Jane wants me to like the cousins thing. The fact that they are cousins is mentioned every other page and Sir Thomas seems worried that later in life they will like each other. I don’t know if… I’m just not sure how I feel about it yet.

I was astonished at how some characters that seemed in the right in the shorter version of the book were really stuck up, rich idiots in the larger one. The girls, the adults—everyone is holding Fanny’s social standing against her. Overall I ended up liking Fanny way more than I expected. My favorite parts were all mentions of the pug. I am hoping to see him (or is it her?) develop into his true role as the leading character.

If you missed some (or all) of the guest posts from the series I hosted last year in honour of the 200th anniversary, you can read them here: An Invitation to Mansfield Park.

May 1, 2015

Anne and Gilbert After the Happy Ending

I didn’t like Anne of Windy Poplars when I was ten and I don’t like it now. I remember disliking Anne’s letters to Gilbert, but I had forgotten why. My recent rereading, inspired by the Green Gables Readalong hosted by Lindsey Reeder, reminded me that I found the epistolary genre boring and that I wanted to read more about the relationship between Anne and Gilbert. Most of the book consists of letters she writes to him during the three years of their engagement when she’s teaching in Summerside, PEI and he’s attending medical school in Kingsport, Nova Scotia (a.k.a. Halifax). This time around, I thought I might appreciate the book more, because over the years other epistolary novels, such as Jane Austen’s Lady Susan and Lynn Coady’s The Antagonist (radically different – and both so good!), have persuaded me of the merits of the genre. No such luck. I think the novel would have been much more interesting if it had included letters from Gilbert as well as from Anne.

Anne’s voice is as lively as ever, as she recounts stories about the entertaining and exasperating characters she meets in Summerside, but while she sometimes rhapsodizes about her love for Gilbert and her dreams about their future life together, she almost never shows any interest in his life and what he’s doing during those three long years. I was surprised Gilbert didn’t break off the engagement. He’s conspicuously absent from this book. When Anne goes home to Green Gables for the summer the letters stop – which would make sense if the novel were composed entirely of letters, but it isn’t. There are several passages of third person narration that appear in between her letters, yet they provide more of the same – Anne’s experiences with the people of Summerside.

Perhaps Montgomery left Gilbert out of the story because by the end of the previous book in the series, Anne of the Island, he and Anne have resolved their differences and are blissfully happy. There’s no conflict between them left to dramatize, so instead she focuses on conflicts with the infamous Pringles and other characters. But I would think Gilbert would have plenty to object to in Anne’s self-centred, rambling letters that appear to show no interest in his life and his experiences at medical school.

Anne says she thinks she’s “scandalously in love” with Gilbert, yet there’s very little evidence to support that claim. She refers to the “beautiful two months” they share during the first summer at home in Avonlea, but we don’t hear any details, and even when she sees Gilbert when they’re home for Christmas in the second year, he’s mentioned only in passing – at one point he drives her and her friend Katherine to see Diana and her new baby girl. By the second summer, he’s even further away because he’s “gone west to work on a new railroad that was being built” (which struck me as a particularly vague statement given that Montgomery lived for a year in Saskatchewan and could very easily have specified which part of “the west” Gilbert travels to).

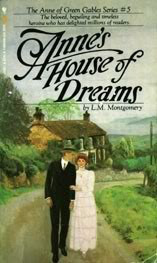

Even if Montgomery decided she didn’t want to include letters from him at all, she could still have revealed more about his years of medical training through Anne’s responses to his letters, or she could have described conversations between them when they meet in Avonlea during the summers. I know she wrote the novel after she had already published books that describe later episodes in Anne’s life, including Anne’s House of Dreams (1917), Rainbow Valley (1919), and Rilla of Ingleside (1921) (see L.M. Montgomery Online for more details). Anne of Windy Poplars wasn’t published until 1936, and I can see that it would have been a challenge to write something that fit in with the other novels.

I suppose my disappointment comes from my expectation, based on the ending of Anne of the Island, that the next book would follow continuing developments in the relationship between the heroine and her hero. And I guess Montgomery was facing the challenge, in both this novel and the later ones in the Anne series, of what to write about after the happy ending has already been written. Mary Henley Rubio says in Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings (2008) that “Maud positively hated the tacked on ‘happy ending’ of romance,” and that in Anne of Green Gables she had focused “not on Anne’s finding a man to marry, but on the more ambiguous image of the ‘bend in the road,’” which “pointed a way to interesting ventures in the future, not necessarily to marriage.” I can certainly understand why Montgomery tried hard to avoid the typical romantic ending, and why she held off for so long on bringing Anne and Gilbert together.

If the heroine and hero are happy, one has to find someone else to write about. In this case, it’s the impossible Pringle family (“I have found out there are some decent Pringles,” Anne writes, “… dead ones”). But I still wonder how happy Gilbert would be, reading those letters and knowing that while Anne loves him, she doesn’t pay any attention to what’s happening in his life. And I can’t help but think his frustration just might be a missed opportunity to explore further conflict between the two of them, frustration of the kind that might have made him want to break a slate over her head this time.

Last week I started reading Anne’s House of Dreams and I was glad to see that even at the start there is more about Gilbert’s medical career: “‘Gilbert looks very young for a doctor. I’m afraid people won’t have much confidence in him,’ said Mrs. Jasper Bell gloomily.” There, that’s more like it. Something Anne and Gilbert can object to together.

I wrote the first draft of this post before the sudden and very sad death of Jonathan Crombie, who played the role of Gilbert in the t.v. adaptation of Anne of Green Gables (1985) and its two sequels. I now feel even more sad about the absence of Gilbert Blythe. Sarah Larson wrote a lovely tribute to both Crombie and Gilbert for The New Yorker, “Why We Loved Gilbert Blythe,” in which she describes the “‘Carrots’ slate-smash” as Anne’s “tolerable, I suppose, but not handsome enough to tempt me” moment. This mention of the connection between Anne of Green Gables and Pride and Prejudice sent me back to Miriam Rheingold Fuller’s wonderful essay “Jane of Green Gables: L.M. Montgomery’s Reworking of Austen’s Legacy,” in which she notes also that “Anne’s violent reaction to Gilbert’s teasing recalls Elizabeth’s response to Darcy’s first proposal, with its references to her ‘inferiority.'”

Here are some of the other responses to Anne of Windy Poplars by bloggers participating in the Green Gables Readalong: Naomi of Consumed by Ink and Eva of The Paperback Princess had a more positive experience of rereading the novel than I did, while Courtney at Once Upon a Bookshelf feels that “this book wasn’t true to the spirit of the rest of the series.”

If you’ve read Anne of Windy Poplars, I’d be interested to hear what you think of the book. There were some passages that I did like very much, so I chose a couple of them to highlight here.

At the beginning of the novel, Mrs. Rachel Lynde makes an appearance. Here’s what she says in reply to a comment Anne makes about the freedom she had at Patty’s Place, where she lived when she attended Redmond College:

“Freedom!” Mrs. Lynde sniffed. “Freedom! Don’t talk like a Yankee, Anne.”

I liked Anne’s reaction to Hazel Marr’s dramatic speeches (such as, “Oh, I don’t know if I hate you the most or pity you the most! Oh, how could you treat me like this … after I’ve loved you so … trusted you so … believed in you so!”):

“You can’t have many exclamation points left,” thought Anne, “but no doubt the supply of italics is inexhaustible.”

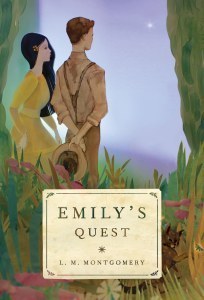

This line made me think of the advice Emily Starr receives from her favourite teacher, Mr. Carpenter, in Montgomery’s novel Emily’s Quest: on his deathbed, Mr. Carpenter warns her to “Beware – of – italics.” Good advice to any writer.

I happen to be visiting Prince Edward Island right now and I took a few photos to share with you. If you read my post “Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley” a few weeks ago you’ll know I was planning to visit PEI in March, but wasn’t able to do so because there was a massive snowstorm in the Maritimes and the Confederation Bridge was closed (not that I would have been able to get anywhere near the bridge, with that much snow in my own driveway). Six weeks later, there is still snow on the ground here, and when we arrived on Wednesday it was snowing again. It’s been a hard winter in this part of the world. I’ll definitely have to come back to the Island in the summer.

Victoria-by-the-Sea

Along the Trans Canada Highway

After I took this photo, on the way into Charlottetown, I realized we had stopped on Poplar Island.

April 24, 2015

The Secret Diary of L.M. Montgomery and Nora Lefurgey

For more than a year now, Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney have been writing about friendships between women writers on their blog, SomethingRhymed.com, and when they were preparing to write about L.M. Montgomery, they wrote to ask me for suggestions. Montgomery’s correspondence with G.B. MacMillan and Ephraim Weber is well known, but of course they were looking for a woman writer, so I wrote to recommend Nora Lefurgey, with whom Montgomery kept a joint diary, and they posted their profile of that friendship in the fall.

L.M. Montgomery (left) and Nora Lefurgey. Image used with the kind permission of Heirs of L.M. Montgomery, Inc. and Archival and Special Collections, University of Guelph Library.

(I also suggested Lucy Lincoln Montgomery, a Massachusetts writer Lucy Maud Montgomery corresponded with – apparently they became friends because of the similarity of their names – but I haven’t been able to learn very much about their friendship. If any of you know more about Lucy Lincoln Montgomery, please share in the comments. Maybe someday I’ll write an essay about the two Montgomerys with the Sarah Emsley who works at Headline Publishing….)

Sue Lange, a South Australian writer with a particular interest in Montgomery, first wrote to me last summer after I mentioned her article “L.M. Montgomery’s Halifax: The Real Life Inspiration for Anne of the Island ,” in a blog post about connections between my hometown of Halifax, Nova Scotia and Montgomery’s “Kingsport.” We’ve kept up a regular correspondence ever since, about writing, Montgomery, and Jane Austen (and one of my other favourite authors, Jeanne Birdsall, whose newest book in the Penderwicks series was just published a few weeks ago, and whose writing often includes allusions to both Montgomery and Austen.)

Martello Tower, Point Pleasant Park, Halifax (Kingsport “has in its park a martello tower…”)

Inspired by what Emily and Emma Claire wrote about the secret joint diary, Sue sent me an excerpt from the book she’s working on, called Hooked on Montgomery: The Hooked and Braided Rugs in the Life of L.M. Montgomery, and with her permission, I’m pleased to share it with all of you here. I would have posted it last fall, except that, as many of you will recall, I was totally wrapped up in the Mansfield Park celebrations and therefore had trouble finding time for Montgomery. This month, however, I’ve been rereading Anne of Windy Poplars and thinking about Montgomery’s novels again. So – with thanks to Sue for her patience – here is her guest post that ties together rug hooking, friendship, and that fascinating secret diary.

Sue is a regular contributor to The Shining Scroll (published by the L.M. Montgomery Literary Society) and Rug Hooking magazine, and her current research focuses on L.M. Montgomery, Kate Douglas Wiggin, Louisa May Alcott, and Laura Ingalls Wilder. It’s been lovely to meet new friends like Sue, Emily, and Emma Claire through the world of blogging, and I’m happy to have this opportunity to introduce them and their writing to you.

L.M. Montgomery and her friend Nora Lefurgey make a number of witty references to rug hooking in the collaborative “burlesque” diary they kept from January to June 1903, in which they catalogued their various larks and jokes.

Twenty-three-year-old Nora Lefurgey had moved to Cavendish in late 1902 to teach at the local school. She was just five years younger than Montgomery and the two women quickly discovered they were kindred spirits. Within a few months of arriving, Lefurgey moved from the nearby Laird residence to board instead with Montgomery and her grandmother. Montgomery and Lefurgey would share a lifelong friendship, despite losing contact at some points.

The diary primarily revolves around the alleged pursuit of potential male suitors. In the midst of the teasing banter between the two women (who took turns writing most days) are several humorous and informative references to rug hooking. On March 29, 1903 Montgomery writes,

Nora and I both went visiting yesterday and come home with all the gossip in C. [Cavendish] with which we regaled each other in bed. The main items are “that Mrs. Will Sandy is hooking mats for Townsend. . . .”

Evidently hooking mats (rugs) was gossip worthy, in the eyes of Cavendish women of this era. As Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston explain in The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The P.E.I. Years, 1889-1900, “Will Sandy” was a nickname Montgomery gave her great Uncle William Macneill, who was her maternal grandfather’s brother. Like his parliamentarian father (William Simpson Macneill, known as “Speaker Macneill”), William A. Macneill was a man of local stature and importance. From Montgomery scholar Carolyn Strom-Collins, I learned that Mrs. “Will Sandy” (or rather, Bessie Macneill) was in fact hooking rugs for her son, Townsend, who married Annie McLure around 1903. The rugs she was hooking were to be to be given as a wedding gift to him and his new wife, to decorate their new home.

If Mrs. “Will Sandy” was hooking rugs for her son over the winter it certainly could have set local tongues wagging with speculation that a wedding announcement was imminent. Given the many hours it takes to hook a rug, such as the one Judy Plum makes as a wedding gift for Aunt Hazel in Montgomery’s Pat of Silver Bush, Mrs. “Will Sandy” would have had to start her project well in advance of the wedding date.

Hooked rug made by Mrs. MacLeod (mother-in-law of L.M. Montgomery’s first cousin Heath Montgomery). L.M. Montgomery Heritage Museum, Park Corner, PEI. Photo by Carolyn Strom-Collins.

The connection between rug-making and suitors is further expanded when Lefurgey and Montgomery engage in an especially humorous exchange relating to Montgomery’s alleged unsuccessful pursuit of two older bachelor farmers, including fifty-one-year-old Howard Simpson from Bay View. Lefurgey writes,

Thursday Maud went up to Dan Simpson’s to cut rags! (Ahem.) I have heard of girls going out to hook but to cut rags . . . however, she can’t hook so she said she would cut rags. The simple truth is she thought she would “hook” into Howard and cut the “widow” out! But she got nicely left and she was so disappointed that she took sick as soon as she got home and had time to think it all over.

“Outraged” at this slur, Montgomery provides an alternative explanation, refuting Lefurgey’s “mis-statements” about her motives:

Tuesday morning we spent quilting at Uncle John’s. Thursday morning Lu and I went to Dan Simpson’s. Nora could not go, hence her jealous slur about me and Howard! I did go to cut rags and I cut them! As for “hooking” Howard, all I’ve got to do is to raise my finger and everybody knows it. His “widder” is quite welcome to him and no sour grapes about it.

One can understand why Lefurgey was somewhat dubious about Montgomery’s motives, as most consider the task of cutting rags mundane and dreary. The exchange between the two young friends illustrates that rug hooking at that time was a means to gain favour with a beau and a legitimate way to spend time socially with a suitor’s family.

The third rug hooking reference shows that Montgomery’s first cousin Lucy Macneill also participated in rug hooking. Montgomery writes, “Tuesday evening Nora went over to help Lucy hook and dragged me along too, not even giving me time to comb my hair.” The secret diary shows how popular the practice of rug hooking was in P.E.I. at the beginning of the twentieth century. It was not only Montgomery’s older female relatives, such as her aunt Annie Campbell, who participated, but also her contemporaries, including Lefurgey and Lucy Macneill.

During this period of her life Montgomery complained bitterly that her grandmother gave her constant worry with her intolerant and childish behavior, particularly towards strangers who came to the house. It seems productive social occasions such as sewing, quilting, and hooking bees provided necessary social stimulation and a chance to escape the drudgery of household chores and lack of companionable conversation at home.

Admittedly though, Montgomery’s preference was to create stories, rather than rugs, much as she admired them and enjoyed the social aspects of regular hookings, where she amiably cut rags and chatted.

Quotations from the secret diary are taken from The Intimate Life of L.M. Montgomery, edited by Irene Gammel (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005).

For further reading:

Lucy Maud Montgomery: The Gift of Wings, by Mary Henley Rubio (Toronto: Doubleday Canada, 2008).

The Complete Journals of L.M. Montgomery: The PEI Years, 1901-1911, edited by Mary Henley Rubio and Elizabeth Hillman Waterston (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Postscript from Sarah: I just started reading Anne’s House of Dreams for the Green Gables Readalong (I know, when I wrote about Anne of the Island I said I didn’t think I had time to read all the books in the series this year, but I couldn’t resist continuing with Anne of Windy Poplars and now Anne’s House of Dreams) and I came across this comment from Marilla about the braided rugs she plans to give Anne for her new house. Trust Anne to want something old-fashioned instead of the latest thing.

I’m giving Anne that half dozen braided rugs I have in the garret. I never supposed she’d want them – they’re so old-fashioned, and nobody seems to want anything but hooked mats now. But she asked me for them – said she’d rather have them than anything else for her floors. They are pretty. I made them of the nicest rags, and braided them in stripes. It was such company these last few winters.

Next Friday I’ll post about Anne of Windy Poplars (and the reason I don’t like it very much…).

March 20, 2015

Attending Redmond College with Anne Shirley

“It was not exhilarating to be surrounded by crowds of strangers, most of whom had a rather alien appearance, as if not quite sure where they belonged.” This is Anne Shirley’s response to registration day at Redmond College in L.M. Montgomery’s novel Anne of the Island. She and her friend Priscilla “gladly made their escape” from the college in order to retreat to “Old St. John’s Cemetery,” Montgomery’s fictionalized version of the Old Burying Ground in Halifax (which I wrote about here last year), for “the first of many rambles.” Redmond College is based on Dalhousie University and the “quaint old town” of Kingsport described in Anne of the Island is based on Halifax.

Anne of the Island (Tundra, 2014), cover illustration by Elly MacKay

Carol Dobson writes in The Lucy Maud Montgomery Album that Montgomery, like her heroine, “took a regular constitutional to Redmond (Dalhousie), a little less than a mile from the Ladies’ College. The Forrest Building still stands. Once the main administration building and nerve centre of Dalhousie, it is now home to the Department of Nursing. However, its foyer, with the heavy Victorian stairway, makes imagining Anne, Phyl Blake, Gilbert, and Charlie Sloane climbing the stairs to classes or meetings of the Philomathic Society an easy matter.”

Forrest Building, Dalhousie University

The Forrest Building, designed by J.G. Dumaresq, was built in 1887, and until 1914, it was Dalhousie’s only building. The photo above is one I took in 2014. There’s a circa 1930 photo of the building in this story about the “Top 5 Oldest Historic Buildings at Dal.”

On that first day at Redmond, students gather “on the big staircase of the entrance hall,” and in the midst of the crowd, Anne feels “as insignificant as the teeniest drop in a most enormous bucket.” But Priscilla is right that “in a little while we’ll be acclimated and acquainted, and all will be well” – and of course, Anne being Anne, she is soon chasing academic glory while participating in “all the phases” of college life: “the stimulating class rivalry, the making and deepening of new and helpful friendships, the gay little social stunts, the doings of the various societies of which she was a member, the widening of horizons and interests.”

Lindsey Reeder is organizing an Anne of Green Gables Readalong this year, which started with the first book in the series in January and continues with one novel per month, right up to Rilla of Ingleside in August. I love rereading these books and am doing my best to keep up (although I have no illusions about finding time to write a blog post for each one!). If you’re interested, you can follow along with Lindsey by subscribing to her blog and by talking about the books on social media with the hashtag #GreenGablesReadalong.

I was planning to visit PEI this week and I thought I’d take pictures of a couple of L.M. Montgomery-related sites to share with you in this post, but then this happened on Wednesday:

More than 50 cm of snow on top of what we already had in Halifax. So of course I stayed home and watched the six hour Pride and Prejudice miniseries.

Maybe I’ll get to PEI next month. For now, instead of showing you more pictures of the huge snowbanks in either PEI or Nova Scotia, I’ll share this photo from last summer’s trip to the Blue Winds Tea Room in New London, PEI, where I always order the fabulous homemade raspberry cordial. (No currant wine to be had there or anywhere else on the Island, sadly. I’ve always wondered why no one in PEI is producing currant wine for tourists, since that’s what Diana actually drinks in that famous scene in Anne of Green Gables when she thinks she’s having raspberry cordial.)

If you want to read more about connections between Anne of the Island and Halifax, you might be interested in my earlier blog posts listed here: “L.M. Montgomery in Nova Scotia.”

You can see all eight of Elly MacKay’s illustrations for the “Anne” books on her website, along with the covers she did for the three books in Montgomery’s “Emily” series.

And, while I’m on the topic of book covers – if any of you have ever considered choosing clothes to match the covers of the books you’re reading, you might enjoy this fun blog post at Tundra Books: “Fashion Friday: Anne and Emily.” I think the dresses pictured here ought to be available as a set, perhaps even sold with the Montgomery novels. I can think of at least one friend who would buy all the Anne and Emily dresses….

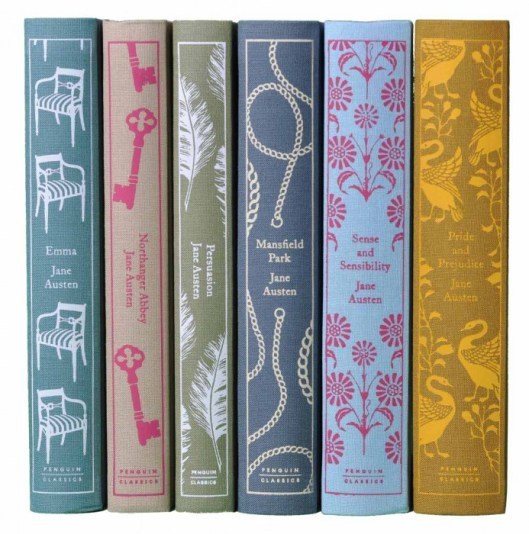

Also – has anyone done something like this for Jane Austen’s novels? I’m imagining a set of six Regency gowns that match these Penguin editions.

Or, better still, a set of costumes that recreate clothes mentioned in the novels, including, for example, a red coat, a blue coat, a muddy petticoat, and a “worked muslin gown” with a “great slit” in it (Pride and Prejudice), a pink satin cloak and a lieutenant’s uniform (Mansfield Park), white, purple, and spotted muslin gowns (Northanger Abbey – see Clothes in Books for a blog post on Isabella Thorpe’s “I wear nothing but purple now”), and so on.

I’m just getting started, but I’ll stop there! I’m sure you can think of many more examples of clothes in both Montgomery’s and Austen’s novels. And I guess it’s no surprise that even when I’m writing about Montgomery, I always come back to Austen.

February 14, 2015

Pauses: Moments in Jane Austen When Nothing and Everything Gets Said

For Valentine’s Day, I’m very happy to share with you this guest post by Nora Bartlett on the moments in Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion in which Jane Austen’s characters say nothing. Nora is currently writing a book on silence and listening in Austen’s fiction. She was born in upstate New York but has lived most of her adult life in Scotland, where she has taught for over twenty years in the School of English at St. Andrews University, also working with adults in various Lifelong Learning programs. She tells me she misses North American snow – and I have to say that with all the storms we’ve had recently in Halifax, I would gladly send her some of ours if I could.

I’m starting to plan a new series of blog posts to mark the 200th anniversary of Austen’s Emma, which was published on December 25, 1815, and I’m delighted to announce that Nora is writing the first post – on the snow in Emma. More details about the series coming soon! But for now, we can all look forward to Nora’s post on December 25, 2015.

The spirea in my back yard.

The holly at my front door.

About fifteen years ago, Nora says, her love of Jane Austen’s novels “took a more scholarly direction, including in particular an interest in the way her juvenile writing leaves traces in her mature novels.” She’s also interested in the representation in Austen’s work of illness, exhaustion, and eating. She has published occasional poetry and short fiction and non-fiction, along with essays on Austen in Persuasions and in medical journals.

Her analysis of the significance of Austen’s silences is further evidence, I think, that the answer to John Mullan’s question “What matters in Jane Austen?” (the title of his 2012 book) is “Everything matters.” Every word, every silence, every pause.

All of Jane Austen’s novels use the “pause” – a moment of silence, sometimes of listening, sometimes of thinking, which precedes or follows speech – to great effect; the word appears more than a hundred times in her mature novels – but I would like to concentrate on Pride and Prejudice, the “light, and bright, and sparkling” novel famous for its snappy dialogue, and on Persuasion, the novel whose heroine, Anne, does so much listening and who does not herself speak until Chapter 3.

My interest in pauses started with a misremembered one: in the deliriously funny moment in Chapter 38 when Elizabeth, left alone with Mr. Collins on the last day of her stay at the Rosings parsonage, is forced to listen to his effusions about the delights of “this humble parsonage” when augmented by their “intimacy at Rosings,” I had always imagined a “short pause” before “Elizabeth tried to unite civility and truth in a few short sentences.” But in fact Mr. Collins’ bulldozer style does not allow any pauses, and Lizzie’s own quiet comments pass unheard in the background while he steams around the room in a kind of ecstasy of self-praise. There are other examples in the novel of his disallowing a pause, or invading it: in the midst of his Chapter 19 proposal to Elizabeth, his concentration on his own feelings is so profound, and his description of them so absurd, that, despite her reluctance to hear him out, “Elizabeth was so near laughing that she could not use the short pause he allowed in any attempt to stop him.”

This is a strong example of how Jane Austen uses the “pause” to create comedy: as in Persuasion, where in Chapter 3 Sir Walter Elliot shows his ignorance of the world, the law, and his own dire economic straits by declaring loftily that he is “by no means” certain “as to the privileges” attached to the tenancy of Kellynch Hall – the tenant may be limited in his access to Kellynch’s “pleasure-grounds … shrubberies … flower gardens.”

After this preposterous statement there is “a short pause” while his steward, Mr. Shepherd, is clearly biting his tongue to keep, either from laughing, or from replying with the sharpness which the comment deserves: he knows more than anyone what a jam the Elliots are in and how much they need this tenant, and he knows the law – but he is used to crawling to Sir Walter, has become of necessity what the Scottish call a “sook,” or suck-up, and will reply, as his clever daughter Mrs. Clay will always reply to the patronizing comments of Sir Walter and Miss Elliot, diplomatically, flatteringly. They are playing a long game with their short pauses.

So the “pause” is often a moment when a character is suppressing a laugh, or an angry reply: it stands for a rebellion that does not take place, or takes place only internally.

But there are other types of pause also, and one occurs in Pride and Prejudice a little later, in Chapter 21, when Jane Bennet has received, and relayed to Elizabeth, the distressing news of the Bingley party’s sudden departure from Netherfield. Elizabeth is listening, and forming her own opinions of, the “high-flown expressions” of Miss Bingley’s letter, but knows Jane’s view of the sisters is different from hers, so replies carefully, “after a short pause,” not showing her own sense that the female Bingleys are treacherous snobs and false friends, because she knows that that would both hurt the tender-hearted, trusting Jane, and alarm her about their brother. Instead she is, like Mr. Shepherd, tactful: “may we not hope that … the delightful intercourse you have known as friends, will be renewed with yet greater satisfaction as sisters.”

In that “short pause” Elizabeth was thinking what to say: and though Jane Austen presents her characters’ thoughts with incomparable depth and subtlety in her use of free-indirect discourse, where the narrative mingles with the character’s thoughts, here she allows the reader to invent or imagine what kind of thinking has gone into those “short pauses”: Mr. Shepherd wants to move the topic on to a more realistic plane, and wants not to lose his job; Elizabeth wants to give her beloved sister the kind of comfort in this unexpected turn of events that she believes is genuinely appropriate to the situation. Both characters, in highly contrasting situations, are taking care with their speech.

But the pauses also produce a kind of realism in the rhythms of speech as Jane Austen’s novels display it: we all know from our own experience of conversation, formal or informal, that we are often required to pause before speaking – like Mr. Shepherd and Elizabeth, we are deciding what to say next. In Pride and Prejudice, despite the “sparkling” reputation of its dialogue, there are many such pauses – even with Mr. Wickham, so easy to talk to that a clever young woman ought to be more on her guard, there are “many pauses” and “trials of other subjects” while Elizabeth tries to maintain her composure as she and Wickham mount their joint attack on Mr. Darcy’s character. And in her talk with Mr. Darcy, there are so many pauses that one is tempted to wonder if Jane Austen is thinking of the famously tongue-tied heroine created by her beloved Fanny Burney in Evelina, who, dancing with her high-born admirer at her first London ball, can say nothing at all.

Elizabeth, not quite so simple, nevertheless experiences in her first dance with Mr. Darcy, “a pause of some minutes,” and is forced to blurt out – here abandoning tact – that there are “no other two people in the room who have less to say for themselves.” Later, in Mr. Darcy’s first, unsuccessful proposal at the Rosings parsonage, there will be “a pause” on his part, in which his thoughts are embodied in physical reactions that Elizabeth cannot help seeing and experiencing – “his complexion became pale with anger, and the disturbance of his mind was visible in every feature” – this “pause was to Elizabeth’s feelings dreadful.” She does not realize, but the reader probably does, how much her feelings are already blending with Darcy’s: the reader can feel the intensity of her erotic response to Darcy – amidst all her resentment and rage – in that “dreadful pause.”

It would be possible to examine pauses in all the novels, but I have not chosen Pride and Prejudice and Persuasion arbitrarily – Anne and Elizabeth are among the heroines to whom Jane Austen gives her own talent for, and love of, the piano. It is well-known that when finally settled in some comfort at Chawton Cottage in 1809, she set up her beloved piano even before she took out her old manuscripts and began reworking them; and that she started each day not by writing but by practicing the piano – here she is more like Anne than like Elizabeth, who will “not take the trouble of practicing.”

“Pause” is a French musical term, known to 18th century English musicians, though the more common term at the time in England for “a notational sign that indicates the absence of a note or notes” was “rest” (Grove/Oxford Music Online, “Rest” [entry by Richard Rastall]). It seems possible to me that Jane Austen, the one musician in an unmusical family, growing up so familiar with the talk and tastes of her Frenchified cousin Eliza de Feuillide, may have been at least aware of the term more common in French for that specific kind of silence which gives shape to musical sound, as the pause gives her dialogue its particular shape – and that she may have used the term consciously. Fielding’s characters sometimes “pause” before speaking, but in all of Tom Jones’s over 1000 pages, only 9 times, versus Pride and Prejudice’s 23, Sense and Sensibility’s 24, Mansfield Park’s 29, Emma’s 17.

In Persuasion, the briefest and greatest of her novels, there are eleven pauses: I have looked at one comic one and want to end with one luminous and serious one, complicated by its being heard not only by those in the conversation, but overheard by the silent, pensive Anne. This is Captain Wentworth and Louisa Musgrove, nutting and flirting in the hedgerows in Chapter 10 while Anne is left alone, neglected by all, feeling no connection with anything but the melancholy autumnal landscape. Louisa, that healthy, lively, commonplace young girl, is expressing her resentment of her sister-in-law Mary’s snobbishness:

“She has a great deal too much of the Elliot pride – we do so wish that Charles had married Anne – I suppose you know he wanted to marry Anne?”

After a moment’s pause, Captain Wentworth said, “Do you mean that she refused him?”

“Oh! Yes, certainly.”

“When did that happen?”

Louisa is not imaginative enough to wonder at this abrupt shift, this surprising interest in Anne, on the part of a man who has been studiously ignoring her for weeks, but the reader thinks his or her way deep into that pause: later Captain Wentworth, referring to that refusal of Charles, tells Anne, “I could not help thinking, ‘was this for me?’” But there is more – as in the later moment when he responds to Mr. Elliot”s admiring glance at Anne on the Cobb at Lyme, he is suddenly seeing Anne again as she had once appeared to him – young and beautiful and desirable, stepping toward him beckoningly, freed from the ghastly nunhood of the years between. There are many moments in the novel which show the ways in which these two cannot get away from each other, but here, as often, it is displayed in a pause, spoken in silence.

Quotations are from the Penguin editions of Pride and Prejudice (1985) and Persuasion (1987).

January 9, 2015

Let’s Bookmark Nova Scotia’s Literary Landmarks

“All of us are better when we’re loved.” The powerful last line of Alistair MacLeod’s International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award-winning novel No Great Mischief is deservedly famous, and the final paragraphs of the novel, including that line, will soon be honoured on a Project Bookmark Canada plaque in Cape Breton, near the Canso Causeway. I wrote an article about this project for the most recent issue of Eastword, the newsletter of the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia, and (with permission) I’ve adapted it to share with you here. This plaque for No Great Mischief will be the very first Bookmark in Nova Scotia, and I hope it will also be possible to honour the work of many more writers with future Bookmarks around the province.

Project Bookmark Canada aims to create a literary map of Canada by placing text from fiction and poetry in the precise locations where those passages are set. The first Bookmark, unveiled in 2009 at the Bloor Street Viaduct in Toronto, was a passage from Michael Ondaatje’s novel In the Skin of a Lion, and since then there have been twelve more Bookmarks across the country. From Vancouver, BC to Woody Point, Newfoundland, these plaques are mapping out what Kristen Den Hartog, author of And Me Among Them, calls a “literary TransCanada highway.” It’s fitting, I think, that the first Bookmark in Nova Scotia will be placed next to the TransCanada itself. And I know many readers will agree it is also fitting that the first Bookmark in Nova Scotia will pay tribute to the work of one of the province’s most beloved writers, Alistair MacLeod.

The Bookmark for No Great Mischief was announced on October 3, 2014 at the Cabot Trail Writers’ Festival, and Miranda Hill, founder and executive director of Project Bookmark Canada, says she hopes the future unveiling of this Bookmark will also take place at the Festival. Supporters of the project include Alistair MacLeod’s family, Destination Cape Breton, the Government of Nova Scotia, the Cabot Trail Writers’ Festival, and many others, including the Writers’ Federation of Nova Scotia. Our President, Sylvia Gunnery, the WFNS board and staff, and many individual members have demonstrated enthusiastic support for the project from the very beginning, and it’s been clear that there’s a tremendous desire to honour the work of Nova Scotia writers in general, and of Alistair MacLeod in particular, through partnering with Project Bookmark Canada to create permanent, physical markers that map our literary landscape.

Project Bookmark Canada would love to hear from anyone who’s interested in supporting the creation of the No Great Mischief Bookmark and future Bookmarks in Nova Scotia, and in helping to add to the list of potential Bookmark passages. There are many ways to help out with these exciting projects.

You could make a donation directly to the No Great Mischief Bookmark, via the “Build a Bookmark” page on Project Bookmark Canada’s website. You could offer suggestions about potential sources of funding. (Each Bookmark costs $10,000 – $12,000.) You could read fiction and/or poetry to identify passages – imagined scenes set in real, identified locations, either in Nova Scotia or elsewhere in Canada – for future Bookmarks. You could share information and news about Project Bookmark Canada with friends, family, and colleagues. You could volunteer at festivals and other events. You could offer to set up, or join, a Project Bookmark Reading Circle that focuses on, say, a particular area of Nova Scotia, or on poetry set in Nova Scotia, or on classic or contemporary fiction set here (or, for that matter, set somewhere else in Canada, if there’s a specific place you’d like to focus on and explore with your group). When you travel across Canada, you could visit, and celebrate, the existing Bookmarks, such as the one in Winnipeg, Manitoba (at the intersection of River and Osborne, at The Gas Station Arts Centre) that honours a passage from Carol Shields’s novel The Republic of Love, or the one in Hamilton, Ontario that marks a passage from John Terpstra’s poem “Giants” (at Sam Lawrence Park).

If you haven’t yet seen the video that was Sheree Fitch’s contribution to the first “Page-Turner” fundraising campaign for Project Bookmark Canada, I encourage you to watch it. In the video, Sheree – with several other Nova Scotia writers and WFNS members serving as a chorus – explains why the project is so important, and offers a suggestion for a future Nova Scotia Bookmark: “Project Bookmark Canada is an exciting initiative. It means we’re going to be able to read our way across Canada. It means we’re going to be able to go to places, like River John where I live, and go to the iron bridge that I can see from my office, and maybe see an excerpt from a wonderful book called Scotch River by my friend Linda Little.” Sheree talks about how Canadian books “teach me what it means to be a part of this country, this landscape,” and how they “help us know that we are connected from coast to coast.”

I’m very happy to be supporting Project Bookmark Canada, particularly through my work on the WFNS Membership Committee. When I was growing up, my family made several summer trips across the country on the TransCanada highway, from Nova Scotia (where I grew up) to Alberta (where I was born, and where most of my relatives lived), and I wish we’d been able to stop and read literary Bookmarks along the way. I’m excited about the prospect of visiting Bookmarks in various literary spots around Nova Scotia as well as in other parts of the country.

If you’re interested in helping out, or have questions, please get in touch with Miranda and Project Bookmark Canada (www.projectbookmarkcanada.ca; @BookmarkCanada) or with me ([email protected]; @Sarah_Emsley). Let’s celebrate great writing about Nova Scotia, starting with Alistair MacLeod’s No Great Mischief.

December 26, 2014

The Happy Endings of Mansfield Park

Thirty-ninth, and last, in a series of guest posts celebrating 200 years of Jane Austen’s Mansfield Park. For more details, open Your Invitation to Mansfield Park.

Happy holidays, everyone, and thank you very much for celebrating Mansfield Park with me this year!

It’s a great pleasure to give the last word in this series to Sheila Johnson Kindred, my friend and frequent collaborator on Austen-related projects, and my fellow co-chair of the Programs Committee for JASNA Nova Scotia. Sheila and I meet regularly for tea to discuss our research and writing and our plans for upcoming JASNA meetings. This past year, we focused on our breakout session for the 2014 JASNA AGM, “Among the Proto-Janeites: Reading Mansfield Park for Consolation in Halifax, Nova Scotia in 1815.” I’m pleased to report that we had a wonderful time presenting the paper in Montreal and discussing the story of Lady Sherbrooke and Mary Wodehouse with our audience – many thanks to everyone who attended! – and that the paper has just been published in Persuasions On-Line. Read about why we think Hilary Mantel is wrong to say that “No one who read it closely was ever comforted by an Austen novel” – you can find our essay at this link.

A July morning (2014) at the Birch Cove estate in Halifax (now Belcher’s Marsh Park), where Lady Sherbrooke and Mary Wodehouse read Mansfield Park in 1815.

There are so many good things to read in this new issue of Persuasions On-Line , including essays by Theresa Kenney, Kathryn Davis, and Elaine Bander, all of whom contributed to “An Invitation to Mansfield Park ,” and the 2013 Jane Austen Bibliography by Deborah Barnum, who was also a contributor.

For many years, Sheila Kindred taught in the Philosophy Department at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax. She has done extensive original research about the life of Jane Austen’s naval brother Captain Charles Austen and his associations with his sister’s novels, and she has presented her research at JASNA AGMs in Quebec City, Philadelphia, and New York. She was invited to speak at two Jane Austen Society (UK) conferences, in Halifax in 2005, and in Bermuda in 2010. Her work has been published in Persuasions and The Jane Austen Report, and in the collection of essays I edited for the Jane Austen Society following their 2005 Halifax conference, Jane Austen and the North Atlantic.

What begins must eventually end and it is now time for the “last post.” Sarah’s “Invitation to Mansfield Park” has sparked a wonderful set of blog posts and an ongoing debate. Thank you, Sarah, for making all this possible. There has been much enjoyment and much food for thought. I consider it a pleasure and a challenge to have a last word on Jane Austen’s last words in Mansfield Park. Here are her two concluding paragraphs:

With so much merit and true love, and no want of fortune or friends, the happiness of the married cousins must appear as secure as earthly happiness can be. – Equally formed for domestic life, and attached to country pleasures, their home was the home of affection and comfort; and to complete the picture of good, the acquisition of Mansfield living by the death of Dr. Grant occurred just after they had been married long enough to begin to want an increase in income, and to feel their distance from the paternal abode an inconvenience.

On that event, they removed to Mansfield, and the parsonage there, which under each of its two former owners, Fanny had never been able to approach but with some painful sensation of restraint or alarm, soon grew as dear to her heart, and thoroughly perfect in her eyes, as every thing else within the view and patronage of Mansfield Park had long been.

– From Mansfield Park, Chapter 48 (London: Penguin, 1985)

Sheila’s well-worn Penguin copy of Mansfield Park.

Jane Austen begins her final chapter with the words “let others dwell on guilt and misery.” She wishes instead to “restore everybody not greatly at fault to tolerable comfort.” She clearly signals the novel is about to culminate in a happy ending. In fact, Austen gives us a double deal. The final two paragraphs present two equally happy endings but from different perspectives. Or do they? In considering the double endings of the novel, I also want to address their intent and impact.

In the first paragraph, Jane Austen invites us to track selected events in Fanny’s very happy marriage to Edmund. The tone of the narrative voice is warm and approving; their reward is to enjoy more than “tolerable comfort.” We are told that their “home [at Thornton Lacey] was a home of comfort and affection.” (Notice that Austen repeats, for emphasis, the important idea that this place is a home.) Then “the picture of good” is completed when the Mansfield parsonage suddenly becomes available on the death of Dr. Grant. We learn just enough to sustain an ongoing interest in the course and chronology of Fanny and Edmund’s married life. It is evident that they will be more financially secure (it has been estimated that the two livings of Thornton Lacey and Mansfield could be worth as much as £1500 annually). This fact, together with their wish to be closer to the “paternal abode,” prompts speculation about why these changes in circumstances are so welcome. It seems as if Fanny may be pregnant, if not already the mother of young children, a state of affairs which would surely add to their married happiness.

In this concise description of Fanny and Edmund’s current situation, there is the suggestion of a natural, even organic progression of events. The parsonage conveniently became available “just after” they had reason to desire it for themselves. This ordering of occurrences underlines the conviction that it is right that Fanny and Edmund are to become the meritorious custodians of the parsonage and that Fanny will be influential in the moral, social, and cultural sphere of the Mansfield estate.

Sheila says she’s always thought this house on the Godmersham estate looks like a perfect Austen house, perhaps a parsonage. (Photo by Hugh Kindred)

Here is a natural happy ending for the novel. But it does not conclude here for Jane Austen adds a further tantalizing paragraph. Note how the narrative voice changes. This last paragraph continues the factual account of the previous one, but it moves away from a description of where and when Fanny and Edmund will be making their home. Rather, it records Fanny’s own greatly altered attitude to the parsonage. As in much of the novel, Fanny’s inner life is brought sharply into focus. We are reminded of her former negative thoughts and intense feelings about the parsonage owing to those who had previously lived there, feelings which are now replaced by positive emotions, terms of endearment and the language of superlatives. To the extent that Mansfield Park is, perhaps more than any other of Austen’s novels, save Persuasion, the story of the heroine’s internal and reflective life, this paragraph also presents an appropriately happy conclusion: Mansfield Park and the parsonage become in the end “thoroughly perfect in [Fanny’s] eyes.”

Yet, in identifying Fanny’s happy state of mind, Austen establishes a sharp counterpoint with her earlier feelings towards the parsonage which she “had never been able to approach but with some painful sensation of restraint and alarm.” In a single sentence we are reminded of the torments of spirit that Fanny has suffered, which were administered by the evil Mrs. Norris and the conniving Crawfords. Mrs. Norris’s treatment of Fanny over the course of eight and a half years, before she was banished with Maria from Mansfield, was simply intolerable. Mary Crawford’s conduct towards Fanny made her feel uncomfortable and restrained. Fanny was perpetually on guard and felt constrained to hide any hint of her own love for Edmund. She was increasingly distressed that Mary might win Edmund’s affections and become his wife. As for Henry Crawford, she found his determined pursuit of her affections utterly alarming.

Austen’s acknowledgment of Fanny’s history of painful sensations is telling, for it reminds us that, as the novel progresses, Fanny did find the strength to be less timid and the courage to be more autonomous. Fanny was greatly discomforted but not cowed by her tormentors. In fact, Fanny displays courage, fortitude, and forbearance. Austen seems to invite us to approve this behaviour as virtuous conduct. Fortitude and forbearance are necessary in Fanny’s miserable circumstances to sustain her in holding to her principle regarding marriage. For Fanny, that is marriage to Edmund, not Henry, for happiness in marriage is, in Austen’s lexicon, only achieved with someone both truly loved and esteemed.

With that fulfilled by her union with Edmund, it is not surprising that Fanny’s concluding endorsement of Mansfield Park is so fulsome. But is Fanny justified in subjectively reaching this conclusion, or is her view of the situation an example of seeing Mansfield through rose-coloured glasses? She was often treated in a way that required gratitude and subservience, states of mind which did not encourage independent and critical thinking. She has been the victim of cruelty, discrimination, and misunderstanding on the part of many of its inhabitants. How could Fanny have forgotten this treatment?

To answer this question we need to look back into the history of Fanny’s earlier judgments about Mansfield Park and to the ostensible reasons for them. Her disquiet and discomfort in living at Mansfield are relieved by the news she is to return to her original home in Portsmouth. But her joy at the imagined warmth of her reception and life among her immediate family is dispelled by its real condition – all noise and squalor. At Portsmouth she “could think of nothing but Mansfield, its beloved inmates, its happy ways.” She recalls its “elegance, propriety, regularity and harmony and – perhaps, above all, the peace and tranquility” (Chapter 39). Fanny’s sentiments at this point may exhibit wishful thinking – the desire to call to mind all the positive features of Mansfield that her memory can conjure up. Certainly her point of view seems highly coloured.

Yet within the first week back among the Prices she realizes that “though Mansfield Park might have some pain, Portsmouth could have no pleasures” (Chapter 39). She persists in this attitude. After three months in the Prices’ home, she reflects on the realization that “Portsmouth was Portsmouth; Mansfield was home” (Chapter 45). It is at Mansfield Park that she feels useful and wanted. Indeed her sense of self is tied to the Mansfield community despite the misfortunes she has had to endure there in the past.

By the end of the novel (Chapter 48), all Fanny’s miseries and anxieties have been dispelled, and replaced by a truly congenial atmosphere at Mansfield Park. The bad influences – Mrs. Norris, Maria, Mary and Henry Crawford – have been permanently excluded from the Mansfield community. Sir Thomas has realized the errors of his ways as head of the Mansfield family and has reformed his attitudes, especially towards Fanny, with whom he has established a “mutual attachment” which was “very strong.” The change of personnel is probably sufficient reason for Fanny’s fond conclusion about the excellence of Mansfield Park. But Austen gives us a further insight. She points us towards the happy improvements that Fanny herself will make possible. She leaves us with a Fanny who is no longer the timid, meek girl who arrived at Mansfield Park at the age of ten. She has been replaced with a young woman of sense and strength of character, who is now confident of her place in the Mansfield community. Fanny has become the “true daughter of Mansfield Park,” and her standards and convictions will set an ongoing example of goodness and virtuous behaviour.

To read more about all the posts in this series, visit An Invitation to Mansfield Park. Many, many thanks to everyone who participated in the series, by reading, by contributing guest posts and comments, and by sharing links to the series with other readers.

This is the first time I’ve hosted a party that lasted for the better part of eight months. Back in the fall of 2013, when I first mentioned to Sheila and to Elaine Bander, Coordinator of the 2014 JASNA AGM, that I was thinking of putting together a celebration of this complex, challenging, endlessly fascinating novel, I had no idea just how big the party would become, or how much of 2014 I would spend corresponding with contributors and talking about Mansfield Park over email, in person, and on the blog. It’s been a delight to introduce you to each other, to listen to the conversations at this party, and to participate in some of the discussions as time allowed.

I continue to be in awe of Jane Austen’s achievement in this brilliant novel. Hosting this blog series has been a fabulous experience, and I’m grateful to all of you for coming to the party.

Let me know if you’re interested in celebrating 200 years of Emma with me in 2016….

In the meantime, however, I’ll see you in 2015. Best wishes for a wonderful year!