Michael Greger's Blog, page 13

August 6, 2024

How to Treat High Lp(a), an Atherosclerosis Risk Factor

What could help explain severe coronary disease in someone with a healthy lifestyle who is considered to be at low cardiovascular disease risk? A young man ended up in the ER after a heart attack and was ultimately found to have severe coronary artery disease. Given his age, blood pressure, and cholesterol, his ten-year risk of a heart attack should have only been about 2 percent, but he had a high lipoprotein(a), also known as Lp(a). In fact, it was markedly high at 80 mg/dL, which may help explain it. You can see the same in women: a 27-year-old with a heart attack with a high Lp(a). What is Lp(a), and what can we do about it?

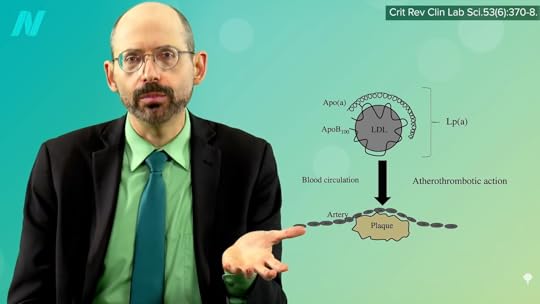

As I discuss in my video Treating High Lp(a): A Risk Factor for Atherosclerosis, Lp(a) is an “underestimated cardiovascular risk factor.” It causes coronary artery disease, heart attacks, strokes, peripheral arterial disease, calcified aortic valve disease, and heart failure. And these can occur in people who don’t even have high cholesterol—because Lp(a) is cholesterol, as you can see below and at 1:15 in my video. It’s an LDL cholesterol molecule linked to another protein, which, like LDL, transfers cholesterol into the lining of our arteries, contributing to the inflammation in atherosclerotic plaques. But “this increased risk caused by Lp(a) has not yet gained recognition by practicing physicians.”

“The main reason for the limited clinical use of Lp(a) is the lack of effective and specific therapies to lower Lp(a) plasma levels.” Because “Lp(a) concentrations are approximately 90% genetically determined,” the conventional thinking has been you’re just kind of born with higher or lower levels and there isn’t much you can do about it. Even if that were the case, though, you might still want to know about it. If it were high, for instance, that would be all the more reason to make sure all the other risk factors that you do have more control over are as good as possible. It may help you quit smoking, for example, and motivate you to do everything you can to lower your LDL cholesterol as much as possible.

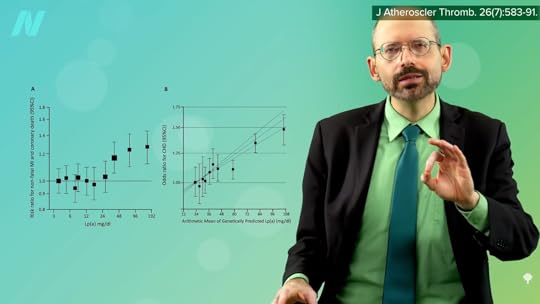

Lp(a) levels in the blood can vary a thousand-fold between individuals, “from less than 0.1 mg/dL to as high as 387 mg/dL.” You can see a graph of the odds of heart disease at different levels in the graph below and at 2:20 in my video. Less than 20 mg/dL is probably optimal, with greater than 30 to 50 mg/dL considered to be elevated. Even when the more conservative threshold of greater than 50 mg/dL is used, that describes about 10 to 30 percent of the global population, an estimated 1.4 billion people. So, if we’re in the one in five people with elevated levels, what can we do about it?

The way we know that Lp(a) causes atherosclerosis is that we can put it to the ultimate test. There is something called apheresis, which is essentially like a dialysis machine where they can take out your blood, wash out some of the Lp(a), and give your blood back to you. And when you do that, you can reverse the progression of the disease. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:06 in my video, atherosclerosis continues to get worse in the control group, but it gets better in the apheresis group. This is great for proving the role of Lp(a), but it has limited clinical application, given the “cost, limited access to centers, and the time commitment required for biweekly sessions of 2 to 4 h each.”

It causes a big drop in blood levels, but they quickly creep back up, so you have to keep going in, as you can see in the graph below and at 3:26 in my video, costing more than $50,000 a year.

There has to be a better way. We’ll explore the role diet can play, next.

I’ve been wanting to do videos about Lp(a), but there just wasn’t much we could do about it until now. So, how do we lower Lp(a) with diet? Stay tuned for the exciting conclusion in my next video.

What can we do to minimize heart disease risk? My video How Not to Die from Heart Disease is a good starting point.

August 1, 2024

Eat Quinoa and Lower Triglycerides?

How do the nutrition and health effects of quinoa compare to other whole grains?

“Approximately 90% of the world’s calories are provided by less than one percent of the known 250,000 edible plant species.” The big three are wheat, corn, and rice, and our reliance on them may be unsustainable, given the ongoing climate crisis. This has spurred new interest in “underutilized crops,” like quinoa, which might do better with drought and heat.

Quinoa has only recently been introduced into the Northern Hemisphere, but humans have been eating quinoa for more than 7,000 years. Is there any truth to its “superfood” designation, or is it all just marketing hooey?

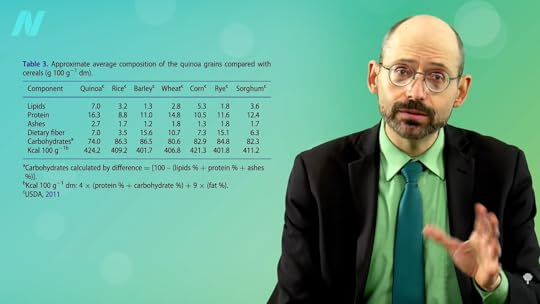

Quinoa is a “pseudograin,” since the plant it comes from isn’t a type of grass. “Botanically speaking quinoa is an achene, a seed-like fruit with a hard coat,” and it has a lot of vitamins and minerals, but so do all whole grains. It also has a lot of protein. As you can see below and in a series of graphs starting at 1:05 in my video Benefits of Quinoa for Lowering Triglycerides, quinoa has more protein than other grains, but since when do we need more protein? Fiber is what we’re sorely lacking, and its fiber content is relatively modest, compared to barley or rye. Quinoa is pretty strong on folate and vitamin E, though, and it leads the pack on magnesium, iron, and zinc. So, it is nutritious, but when I think superfood, I think of something with some sort of special clinical benefit. Broccoli is a superfood, strawberries are a superfood, and so is garlic, but quinoa? Consumer demand is up, thanks in part to “perceived health benefits,” and it has all sorts of purported benefits in lab animals, but there have been very few human studies.

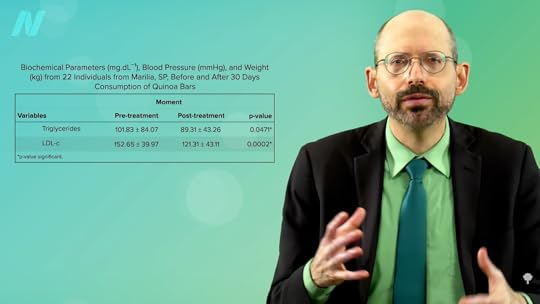

The first trial was a before-and-after study of quinoa granola bars that showed drops in triglycerides and cholesterol, as you can see below and at 1:53 in my video, but it didn’t have a control group, so we don’t know how much of that would have happened without the quinoa. The kind of study I want to see is a randomized controlled trial. When researchers gave participants about a cup of cooked quinoa every day for 12 weeks, they experienced a 36 percent drop in their triglycerides. That’s comparable to what one gets with triglyceride-lowering drugs or high-dose fish oil supplements.

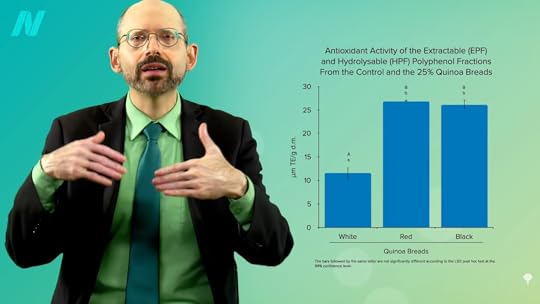

Which is better, regular quinoa or red quinoa? As you can see in the graph below and at 2:22 in my video, the red variety has about twice the antioxidant power, leading the investigators to conclude that red quinoa “might…contribute significantly to the management and/or prevention of degenerative diseases associated with free radical damage,” but it’s never been put to the test.

What about black quinoa? Both red and black quinoa appear to be equally antioxidant-rich, both beating out the more conventional white variety, as you can see in the graph below and at 2:46 in my video.

The only caveat I could find is to inform your doctor before your next colonoscopy or else they might mistake quinoa for parasites. As reported in a paper, a “colonoscopy revealed numerous egg-like tan-yellow ovoid objects, 2 to 3 mm in diameter, of unclear cause,” but they were just undigested quinoa.

For more on the superfoods I mentioned, check the related posts below.

Isn’t fish oil important to heart health? Find out in my video Is Fish Oil Just Snake Oil?.

July 30, 2024

Obesity and a Toxic Food Environment

Implausible explanations for the obesity epidemic serve the needs of food manufacturers and marketers more than public health and an interest in truth.

When it comes to uncovering the root causes of the obesity epidemic, there appears to be manufactured confusion, “with major studies reasserting that the causes of obesity are ‘extremely complex’ and ‘fiendishly hard to untangle,’” but having just reviewed the literature, it doesn’t seem like much of a mystery to me.

It’s the food.

Attempts at obfuscation—rolling out hosts of “implausible explanations,” like sedentary lifestyles or lack of self-discipline—cater to food manufacturers and marketers more than the public’s health and our interest in the truth. “When asked about the role of restaurants in contributing to the obesity problem, Steven Anderson, president of the National Restaurant Association stated, “Just because we have electricity doesn’t mean you have to electrocute yourself.” Yes, but Big Food is effectively attaching electrodes to shock and awe the reward centers in our brains to undermine our self-control.

It is hard to eat healthfully against the headwind of such strong evolutionary forces. No matter what our level of nutrition knowledge, in the face of pepperoni pizza, “our genes scream, ‘Eat it now!’” Anyone who doubts the power of basic biological drives should see how long they can go without blinking or breathing. Any conscious decision to hold your breath is soon overcome by the compulsion to breathe. In medicine, shortness of breath is sometimes even referred to as “air hunger.” The battle of the bulge is a battle against biology, so obesity is not some moral failing. It’s not gluttony or sloth. It is a natural, “normal response, by normal people, to an abnormal situation”—the unnatural ubiquity of calorie-dense, sugary, and fatty foods.

The sea of excess calories we are now floating in (and some of us are drowning in) has been referred to as a “toxic food environment.” This helps direct focus away from the individual and towards the societal forces at work, such as the fact that the average child is blasted with 10,000 commercials for food a year. Or maybe I should say ads for pseudo food, as 95 percent are for “candy, fast food, soft drinks [aka liquid candy], and sugared cereals [aka breakfast candy].”

Wait a second, though. If weight gain is just a natural reaction to the easy availability of mountains of cheap, yummy calories, then why isn’t everyone fat? As you can see below and at 2:41 in my video The Role of the Toxic Food Environment in the Obesity Epidemic, in a certain sense, most everyone is. It’s been estimated that more than 90 percent of American adults are “overfat,” defined as having “excess body fat sufficient to impair health.” This can occur even “in those who are normal-weight and non-obese, often due to excess abdominal fat.

However, even if you look just at the numbers on the scale, being overweight is the norm. If you look at the bell curve and input the latest data, more than 70 percent of us are overweight. A little less than one-third of us is normal weight, on one side of the curve, and more than a third is on the other side, so overweight that we’re obese. You can see in the graph below and at 3:20 in my video.

If the food is to blame, though, why doesn’t everyone get fat? That’s like asking if cigarettes are really to blame, why don’t all smokers get lung cancer? This is where genetic predispositions and other exposures can weigh in to tip the scales. Different people are born with a different susceptibility to cancer, but that doesn’t mean smoking doesn’t play a critical role in exploding whatever inherent risk you have. It’s the same with obesity and our toxic food environment. It’s like the firearm analogy: Genes may load the gun, but diet pulls the trigger. We can try to switch the safety back on with smoking cessation and a healthier diet.

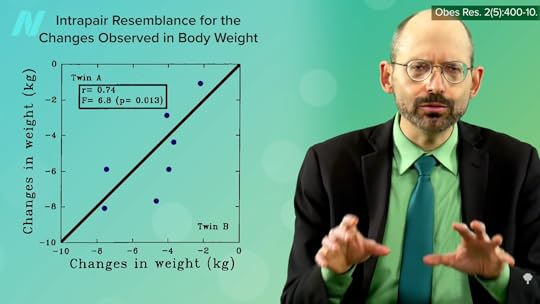

What happened when two dozen study participants were given the same number of excess calories? They all gained weight, but some gained more than others. Overfeeding the same 1,000 calories a day, 6 days a week for 100 days, caused weight gains ranging from about 9 pounds up to 29 pounds. The same 84,000 extra calories caused different amounts of weight gain. Some people are just more genetically susceptible. The reason we suspect genetics is that the 24 people in the study were 12 sets of identical twins, and the variation in weight gain between each of them was about a third less. As you can see in the graph below and at 4:41 in my video, a similar study with weight loss from exercise found a similar result. So, yes, genetics play a role, but that just means some people have to work harder than others. Ideally, inheriting a predisposition for extra weight gain shouldn’t give a reason for resignation, but rather motivation to put in the extra effort to unseal your fate.

Advances in processing and packaging, combined with government policies and food subsidy handouts that fostered cheap inputs for the “food industrial complex,” led to a glut of ready-to-eat, ready-to-heat, ready-to-drink hyperpalatable, hyperprofitable products. To help assuage impatient investors, marketing became even more pervasive and persuasive. All these factors conspired to create unfettered access to copious, convenient, low-cost, high-calorie foods often willfully engineered with chemical additives to make them hyperstimulatingly sweet or savory, yet only weakly satiating.

As we all sink deeper into a quicksand of calories, more and more mental energy is required to swim upstream against the constant “bombardment of advertising” and 24/7 panopticons of tempting treats. There’s so much food flooding the market now that much of it ends up in the trash. Food waste has progressively increased by about 50 percent since the 1970s. Perhaps better in the landfills, though, than filling up our stomachs. Too many of these cheap, fattening foods prioritize shelf life over human life.

But dead people don’t eat. Don’t food companies have a vested interest in keeping their consumers healthy? Such naiveté reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the system. A public company’s primary responsibility is to reap returns for its investors. “How else could we have tobacco companies, who are consummate marketers, continuing to produce products that kill one in two of their most loyal customers?” It’s not about customer satisfaction, but shareholder satisfaction. The customer always comes second.

Just as weight gain may be a perfectly natural reaction to an obesogenic food environment, governments and businesses are simply responding normally to the political and economic realities of our system. Can you think of a single major industry that would benefit from people eating more healthfully? “Certainly not the agriculture, food product, grocery, restaurant, diet, or drug industries,” wrote emeritus professor Marion Nestle in a Science editorial when she was chair of nutrition at New York University. “All flourish when people eat more, and all employ armies of lobbyists to discourage governments from doing anything to inhibit overeating.”

If part of the problem is cheap tasty convenience, is hard-to-find food that’s gross and expensive the solution? Or might there be a way to get the best of all worlds—easy, healthy, delicious, satisfying meals that help you lose weight? That’s the central question of my book How Not to Diet. Check it out for free at your local library.

This is it—the final video in this 11-part series. If you missed any of the others, see the related posts below.

July 25, 2024

Corporate Influence and Our Epidemic of Obesity

Like the tobacco industry adding extra nicotine to cigarettes, the food industry employs taste engineers to accomplish a similar goal of maximizing the irresistibility of its products.

The plague of tobacco deaths wasn’t due just to the mass manufacturing and marketing of cheap cigarettes. Tobacco companies actively sought to make their products even more crave-able by spraying sheets of tobacco with nicotine and additives like ammonia to provide “a bigger nicotine ‘kick.’” Similarly, taste engineers are hired by the food industry to maximize product irresistibility.

Taste is the leading factor in food choice. “Sugar, fat, and salt have been called the three points of the compass” to produce “superstimulating” and “hyper palatability” to tempt people into impulsive buys and compulsive consumption. Foods are intentionally designed to hook into our evolutionary triggers and breach whatever biological barriers help “keep consumption within reasonable limits.”

Big Food is big business. The processed food industry alone brings in more than $2 trillion a year. That affords them the economic might to manipulate not only taste profiles, but public policy and scientific inquiry, too. The food, alcohol, and tobacco industries have all used similar unsavory tactics: blocking health regulations, co-opting professional organizations, creating front groups, and distorting the science. The common “corporate playbook” shouldn’t be surprising, given the common corporate threads. At one time, for example, tobacco giant Philip Morris owned both Kraft and Miller Brewing.

As you can see below and at 1:45 in my video The Role of Corporate Influence in the Obesity Epidemic, in a single year, the food industry spent more than $50 million to hire hundreds of lobbyists to influence legislation. Most of these lobbyists were “revolvers,” former federal employees in the revolving door between industry and its regulators, who could push corporate interests from the inside, only to be rewarded with cushy lobbying jobs after their “public service.” In the following year, the industry acquired a new weapon—a stick to go along with all those carrots. On January 21, 2010, the Supreme Court’s five-to-four Citizen’s United ruling permitted corporations to spend unlimited amounts of money on campaign ads to trash anyone who dared stand against them. No wonder our elected officials have so thoroughly shrunk from the fight, leaving us largely with a government of Big Food, by Big Food, and for Big Food.

Globally, a similar dynamic exists. Weak tea calls from the public health community for voluntary standards are met not only with vicious fights against meaningful change but also massive transnational trade and foreign investment deals that “cement the protection of their [food industry] profits” into the laws of the lands.

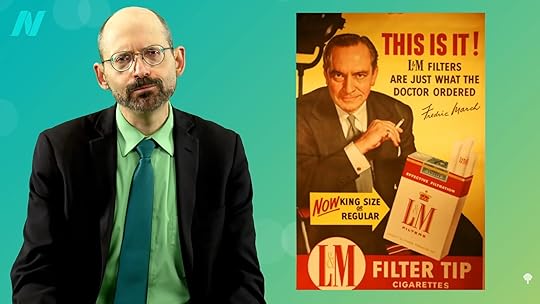

The corrupting commercial influence extends to medical associations. Reminiscent of the “just what the doctor ordered” cigarette ads of yesteryear, as you can see below and at 3:05 in my video, the American Academy of Family Physicians accepted millions from The Coca-Cola Company to “develop consumer education content on beverages and sweeteners.”

On the front line, fake grassroots “Astroturf” groups are used to mask the corporate message. RJ Reynolds created Get Government Off Our Back (memorably acronymed GGOOB), “a front group created by the tobacco industry to fight regulation,” for instance. Americans Against Food Taxes may as just as well be called “Food Industry Against Food Taxes.” The power of front group formation is enough to bind bitter corporate rivals; the Sugar Association and the Corn Refiners Association linked arms with the National Confectioners Association to partner with Americans for Food and Beverage Choice.

Using another tried-and-true tobacco tactic, research front groups can be used to subvert the scientific process by shaping or suppressing the science that deviates from the corporate agenda. Take the trans fat story. Food manufacturers have not only “long denied that trans fats were associated with disease,” but actively “worked to limit research on trans fats” and “discredit potentially damaging findings.”

At what cost? The global death toll from foods high in trans fat, saturated fat, salt, and sugar is at 14 million lost lives every year. The inability of countries around the world to turn the tide on obesity “is not a failure of individual will-power. This is a failure of political will to take on big business,” said the Director-General of the World Health Organization. “It is a failure of political will to take on the powerful food and soda industries.” She ended her keynote address before the National Academy of Medicine entitled “Obesity and Diabetes: The Slow-Motion Disaster” with these words: “The interests of the public must be prioritized over those of corporations.”

Are you mad yet? To sum up my answer to the question underlying my What Triggered the Obesity Epidemic? webinar, it’s the food. I close next with my wrap-up video: The Role of the Toxic Food Environment in the Obesity Epidemic.

This was part of an 11-part series. See the related posts below.

If the political angle interests you, check out:

Big Food Using the Tobacco Industry Playbook How Smoking in 1959 Is Like Eating in 2019 Sugar Industry Attempts to Manipulate the Science The Food Industry Wants the Public Confused About Nutrition A Political Lesson on the Power of the Food IndustryJuly 23, 2024

Should We Take Any Responsibility for the Obesity Epidemic?

The power of the “eat more” food environment can overcome our conscious controls.

Food and beverage companies frame body weight as “a matter of personal choice.” Even when we aren’t distracted, the power of the “eat more” food environment may sometimes overcome our conscious controls of overeating. One look around the room at a dietician convention can tell you that even nutrition professionals are vulnerable to the aggressively marketed ubiquity of tasty, cheap, convenient calories. This suggests there are aspects of our eating behaviors “that defy personal insight or are below individual awareness,” flying below the radar of conscious awareness. Appetite physiologists call the result of these subconscious actions “passive overconsumption.”

Remember that brain scan study where the thought of a milkshake lit up the same reward pathways in the brain as substance abuse? That was triggered just by a picture of a milkshake. Dopamine gets released, cravings get activated, and we’re motivated to eat. Intellectually, we know it’s just an image, but our lizard brain sees survival. It’s just a reflexive response over which we have little control, which is why marketers ensure there are pictures of milkshakes and their equivalents everywhere.

As I discuss in my video The Role of Personal Responsibility in the Obesity Epidemic, maintaining a balance between calories in and calories out feels like a series of voluntary acts under conscious control, but it may be more akin to bodily functions, such as blinking, breathing, coughing, swallowing, or sleeping. You can try to will yourself power over any of these, but by and large, they just happen automatically, driven by ancient scripts.

Not only are food ads ubiquitous, but so is the food. The types of establishments selling food products expanded dramatically in the 1970s and 1980s. Now, you can find candy and snacks at the checkout counters of “gasoline stations, building material outlets, auto parts stores, drug stores, and home furnishing stores” and more. The largest food retailer in the United States is Wal-Mart. You can get that jolt of “dopamine and the associated artificially induced feelings of hunger in modern society” around every turn. Every day, we run the gauntlet.

It’s also become “socially acceptable to eat food at any time of day and anywhere—in cars, in your hand, on the street—places where eating had never been acceptable.” We’ve become a snacking society. Vending machines are everywhere. Daily eating episodes seem to have gone up by about a quarter since the late 1970s, increasing from about four to five occasions a day, potentially accounting for twice the calorie increase attributed to increasing portion sizes. Snacks and beverages alone could account for the bulk of the calorie surplus implicated in the obesity epidemic.

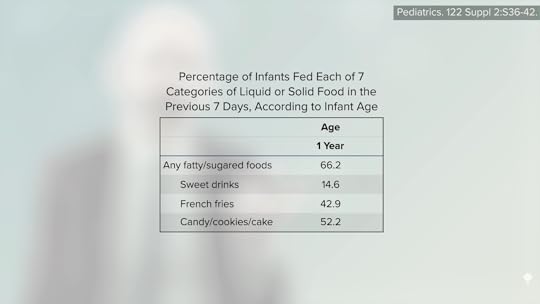

And think of the children. Here we are trying to do the best for our kids, role-modeling healthy habits and feeding them healthy foods, but then they venture out into a veritable tornado of junky food and manipulative messages. A commentary in The New England Journal of Medicine asked: “But why should Mr. and Ms. G.’s efforts to protect their children from life-threatening illness be undermined by massive marketing campaigns from the manufacturers of junk food?” Pediatricians are now encouraged to have the “French Fry Discussion” with parents at the 12-month well-child visit instead of waiting until their kids are two—though even that may be too late. As you can see below and at 3:35 in my video, two-thirds of infants are being fed junk food by their first birthday.

Dr. David Katz may have said it best in the Harvard Health Policy Review: “Those who contend that parental or personal responsibility should carry the day despite these environmental temptations might consider the implications of generalizing the principle. Perhaps children should be encouraged, but not required, to attend school and tempted each morning by alternatives, such as buses to the circus, zoo, or beach.”

It may be helpful to take a step back and think of what’s at stake here. We aren’t just talking about being manipulated into buying a different brand of toothpaste. The obesity pandemic has resulted in millions of deaths and untold suffering. If you aren’t mad yet, brace yourself for my next video: The Role of Corporate Influence in the Obesity Epidemic.

This is the ninth video in my 11-part series. If you missed any of the previous ones, see the related posts below.

July 18, 2024

Are Food Ads Making Us Obese?

We all like to think we make important life decisions, like what to eat, consciously and rationally, but if that were the case, we wouldn’t be in the midst of an obesity epidemic.

The opening words of the Institute of Medicine’s report on the potential threat posed by food ads were: “Marketing works.” Certainly, there is a “large number of well-conducted randomized experiments” I could go through with you that “have shown that exposure to marketing—especially, but not only, advertising—changes people’s eating behavior. Marketing causes people to choose to eat more.” But, what do you need to know beyond the fact that the industry spends tens of billions of dollars a year on it? To get people to drink its brown sugar water, do you think Coca-Cola would spend a penny more than it thought it had to? It’s like when my medical colleagues accept “drug lunches” from pharmaceutical representatives and take offense that I would suggest it might affect their prescribing practices. Do they really think drug companies are in the business of giving away free money for nothing? They wouldn’t do it if it didn’t work.

To give you a sense of marketing’s insidious nature, let me share an interesting piece of research published in the world’s leading scientific journal: “In-Store Music Affects Product Choice” documented an experiment in which French accordion music or German Bierkeller music was played on alternate days in the wine section of a grocery store. As you can see below and at 1:27 in my video The Role of Food Advertisements in the Obesity Epidemic, on the days the French music played in the background, people were three times more likely to buy French wine, and on German music days, shoppers were about three times more likely to buy German wine. And it wasn’t a difference of just a few percent; it was a complete three-fold reversal. Despite the dramatic effect, when shoppers were approached afterward, the vast majority of them denied the music had influence on their choice.

Most of our day-to-day behavior does not appear to be dictated by careful, considered deliberations, even if we’d like to think that were the case. Rather, we tend to make more automatic, impulsive decisions triggered by unconscious cues or habitual patterns, especially when we are “under stress, tired, or preoccupied. This unconscious part of our brain is estimated to function and guide our behaviors at least 95% of the time.” This is the arena where marketing manipulations do most of their dirty work.

The part of our brain that governs conscious awareness may only be able to process about 50 bits of information per second, which is roughly equivalent to a short tweet. Our entire cognitive capacity, on the other hand, is estimated to process more than 10 million bits per second. Because we’re only able to purposefully process a limited amount of information at a time, if we’re distracted or otherwise unable to concentrate, our decisions can become even more impulsive. An elegant illustration of this “cognitive overload” effect was provided from an experiment involving fruit salad and chocolate cake.

Before calls could be made at the touch of a button or the sound of our voice, the seven-digit span of phone numbers in the United States was based in part on the longest sequence most people can recall on the fly. We only seem to be able to hold about seven chunks of information (plus or minus two) in our immediate short-term memory. The study’s setup: Randomize people to memorize either a seven-digit number or a two-digit number to be recalled in another room down the hall. On the way, offer them the choice of a fruit salad or a piece of chocolate cake. Memorizing a two-digit number is easy and presumably takes few cognitive resources. As you can see in the graph below and at 3:52 in my video, under the two-digit condition, most study participants chose fruit salad. Faced with the same decision, most of those trying to keep seven digits in their heads just went for the cake.

This can play out in the real world by potentiating the effect of advertising. Have people watch a TV show with commercials for unhealthy snacks, and, no surprise, they eat more unhealthy snacks compared to those exposed to non-food ads. Or maybe that is a surprise. We all like to think we’re in control and not so easily manipulated. The kicker, though, is that we may be even more susceptible the less we pay attention. Randomize people to the same two-digit or seven-digit memorization task during the TV show, and the snack-attack effect was magnified among those who were more preoccupied. How many of us have the TV on in the background or multi-task during commercial breaks? Research suggests that may make us even more impressionable to the subversion of our better judgment.

There’s an irony in all of this. Calls for restrictions on marketing are often resisted by invoking the banner of freedom. What does that even mean in this context, when research shows how easily our free choices can be influenced without our conscious control? A senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation even went as far as to suggest that, given the dire health consequences of our unhealthy eating habits, “the marketing techniques of which we are unaware should be considered in the same light as the invisible carcinogens and toxins in the air and water that can poison us without our awareness.”

Given the role marketing can play even when we least suspect it, what is the role of personal responsibility in the obesity epidemic? That’s the subject of my next video.

We are winding down this series on obesity, with three videos remaining:

The Role of Personal Responsibility in the Obesity Epidemic The Role of Corporate Influence in the Obesity Epidemic The Role of the Toxic Food Environment in the Obesity EpidemicIf you missed any of the previous videos, see the related posts below.

July 16, 2024

Marketing Takes Off and Obesity Soars

The unprecedented rise in the power, scope, and sophistication of food marketing starting around 1980 aligns well with the blastoff slope of the obesity epidemic.

In the 1970s, the U.S. government went from just subsidizing some of the worst foods to paying companies to make more of them: “Congress passed laws reversing long-standing farm policies aimed at protecting prices by limiting production” and started giving payouts in proportion to output. Extra calories started pouring into the food supply.

Then Jack Welch gave a speech. In 1981, the CEO of General Electric effectively launched the “shareholder value movement,” reorienting the primary goal of corporations towards maximizing short-term returns for investors. This placed extraordinary pressure from Wall Street on food companies to post increasing profit growth every quarter to boost their share price. There was already a glut of calories on the market and now they had to sell even more.

This placed food and beverage CEOs in an impossible bind. It’s not like they’re rubbing their sticky hands together at the thought of luring more Hansels and Gretels to their doom in their houses of candy. Food giants couldn’t do the right thing even if they wanted. They are beholden to investors. If they stopped marketing to kids or tried to sell healthier food or did anything else that could jeopardize their quarterly profit growth, Wall Street would demand a change in management. Healthy eating is bad for business. It’s not some grand conspiracy; it’s not even anyone’s fault. It’s just how the system works.

As I discuss in my video The Role of Marketing in the Obesity Epidemic, given the constant demands for corporate growth and rapid returns in an already oversaturated marketplace, the food industry needed to get people to eat more. Like the tobacco industry before them, it turned to the ad makers. The food industry spends about $10 billion a year on advertising and around another $20 billion on other forms of marketing, such as trade shows, consumer promotions, incentives, and supermarket “slotting fees.” Food and beverage companies purchase shelf space from supermarkets to prominently display their most profitable products. They pay supermarkets. The practice is also known as “cliffing,” because companies “force suppliers to bid against each other for shelf space with the loser pushed ‘over the cliff.’” With slotting fees costing up to $20,000 per item, per retailer, and per city, you can imagine what types of foods get the special treatment. Hint: It ain’t broccoli.

To get a sense of what kind of products merit prime shelf real estate, look no further than the checkout aisle. “Merchandising the power categories on every lane is critical,” reads a trade publication on the “best practices for superior checkout merchandising.” It was referring to candy bars and beverages. Just a 1 percent power category boost in sales could earn a store an extra $15,000 a year. It’s not that publicly traded companies don’t care about their customers’ health. They might, but like most of the leading grocery store chains, their “primary fiduciary responsibility is to increase profits” above other considerations.

For instance, tens of millions of dollars are spent annually advertising a single brand of candy bar. McDonald’s alone may spend billions a year. Now, “the food industry is the biggest spender on advertising of any major sector of the economy.”

“Reagan-era deregulatory policies removed limits on television marketing of food products to children.” Now, the average child may see more than 10,000 TV food ads a year, and that’s on top of “the marketing content online, in print, at school, at the movies, in video games, or at school,” or even on their phones. “Nearly all food marketing to children worldwide promotes products that can adversely affect their health.”

Besides the massive early exposure and ubiquity, food marketing has become “highly sophisticated. With the help of child psychologists, companies began to understand the factors that unconsciously influenced sales. They found out, for example, how to influence children and get them to manipulate their parents.” Packaging was designed to best attract a child’s attention, and then those products are placed at their eye level in the store. You know those mirrored bubbles in the ceilings of supermarkets? They aren’t just for shoplifters. Closed-circuit cameras and GPS-like devices on shopping carts are used to strategize how best to guide shoppers toward the market’s most profitable products. Behavioral psychology is widely applied to increase impulse buying, and eye movement tracking technologies are utilized.

The “unprecedented expansion in the scope, power, and ubiquity of food marketing…coincided with an unprecedented expansion in food consumption in predictable ways.” Some techniques have “skyrocket[ed] from essentially zero to multi-billion-dollar industries” since the 1980s, including “product placement, in-school advertising, event sponsorships.” This led one noted economist to conclude that “the most compelling single interpretation of the admittedly incomplete data we have is that the large increase in obesity is due to marketing.” Yes, innovations in manufacturing and political maneuvering led to a food supply bursting at the seams with close to 4,000 calories a day for us all, but it’s the advances in marketing manipulations that try to peddle that surplus into our mouths.

I think the natural reaction to the suggestion of the power of marketing is: I’m too smart to fall for that. Marketing works on other people, but I can see through it. But that’s what everyone thinks! For a splash of cold water to shake us all out of this delusion, I next bring you some data: The Role of Food Advertisements in the Obesity Epidemic.

Also, for both the role of marketing and food advertisements, check out Friday Favorites: The Role of Marketing and Food Advertisements in the Obesity Epidemic.

This is the seventh in an 11-video series. If you missed any of the first six, check out the related posts below.

July 11, 2024

Do Taxpayer Subsidies Play a Role in the Obesity Epidemic?

Why are U.S. taxpayers giving billions of dollars to support the likes of the sugar and meat industries?

The rise in calorie surplus sufficient to explain the obesity epidemic was less a change in food quantity than in food quality. Access to cheap, high-calorie, low-quality convenience foods exploded, and the federal government very much played a role in making this happen. U.S. taxpayers give billions of dollars in subsidies to prop up the likes of the sugar industry, the corn industry and its high-fructose syrup, and the production of soybeans, about half of which is processed into vegetable oil and the other half is used as cheap feed to help make dollar-menu meat. You can see a table of subsidy recipients below and at 0:49 in my video The Role of Taxpayer Subsidies in the Obesity Epidemic. Why do taxpayers give nearly a quarter of a billion dollars a year to the sorghum industry? When was the last time you sat down to some sorghum? It’s almost all fed to cattle and other livestock. “We have created a food price structure that favors relatively animal source foods, sweets, and fats”—animal products, sugars, and oils.

The Farm Bill started out as an emergency measure during the Great Depression of the 1930s to protect small farmers but was weaponized by Big Ag into a cash cow with pork barrel politics—including said producers of beef and pork. From 1970 to 1994, global beef prices dropped by more than 60 percent. And, if it weren’t for taxpayers “sweetening the pot” with billions of dollars a year, high-fructose corn syrup would cost the soda industry about 12 percent more. Then we hand Big Soda billions more through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as the Food Stamps Program, to give sugary drinks to low-income individuals. Why is chicken so cheap? After one Farm Bill, corn and soy were subsidized below the cost of production for cheap animal fodder. We effectively handed the poultry and pork industries about $10 billion each. That’s not chicken feed—or rather, it is!

This is changing what we eat.

As you can see below and at 2:03 in my video, thanks in part to subsidies, dairy, meats, sweets, eggs, oils, and soda were all getting relatively cheaper compared to the overall consumer food price index as the obesity epidemic took off, whereas the relative cost of fresh fruits and vegetables doubled. This may help explain why, during about the same period, the percentage of Americans getting five servings of fruits and vegetables a day dropped from 42 percent to 26 percent. Why not just subsidize produce instead? Because that’s not where the money is.

“To understand what is shaping our foodscape today, it is important to understand the significance of differential profit.” Whole foods or minimally processed foods, such as canned beans or tomato paste, are what the food business refers to as “commodities.” They have such slim profit margins that “some are typically sold at or below cost, as ‘loss leaders,’ to attract customers to the store” in the hopes that they’ll also buy the “value-added” products. Some of the most profitable products for producers and vendors alike are the ultra-processed, fatty, sugary, and salty concoctions of artificially flavored, artificially colored, and artificially cheap ingredients—thanks to taxpayer subsidies.

Different foods reap different returns. Measured in “profit per square foot of selling space” in the supermarket, confectionaries like candy bars consistently rank among the most lucrative. The markups are the only healthy thing about them. Fried snacks like potato chips and corn chips are also highly profitable. PepsiCo’s subsidiary Frito-Lay brags that while its products represented only about 1 percent of total supermarket sales, they may account for more than 10 percent of operating profits for supermarkets and 40 percent of profit growth.

It’s no surprise, then, that the entire system is geared towards garbage. The rise in the calorie supply wasn’t just more food but a different kind of food. There’s a dumb dichotomy about the drivers of the obesity epidemic: Is it the sugar or the fat? They’re both highly subsidized, and they both took off. As you can see below and at 4:29 and 4:35 in my video, along with a significant rise in refined grain products that is difficult to quantify, the rise in obesity was accompanied by about a 20 percent increase in per capita pounds of added sugars and a 38 percent increase in added fats.

More than half of all calories consumed by most adults in the United States were found to originate from these subsidized foods, and they appear to be worse off for it. Those eating the most had significantly higher levels of chronic disease risk factors, including elevated cholesterol, inflammation, and body weight.

If it really were a government of, by, and for the people, we’d be subsidizing healthy foods, if anything, to make fruits and vegetables cheap or even free. Instead, our tax dollars are shoveled to the likes of the sugar industry or to livestock feed to make cheap, fast-food meat.

Speaking of sorghum, I had never had it before and it’s delicious! In fact, I wish I had discovered it before How Not to Diet was published. I now add sorghum and finger millet to my BROL bowl which used to just include purple barley groats, rye groats, oat groats, and black lentils, so the acronym has become an unpronounceable BROLMS. Anyway, sorghum is a great rice substitute for those who saw my rice and arsenic video series and were as convinced as I am that we need to diversify our grains.

We now turn to marketing. After all of the taxpayer-subsidized glut of calories in the market, the food industry had to find a way to get it into people’s mouths. So, next: The Role of Marketing in the Obesity Epidemic.

We’re about halfway through this series on the obesity epidemic. If you missed any so far, check out the related videos below.

July 9, 2024

Processed Foods and Obesity

The rise in the U.S. calorie supply responsible for the obesity epidemic wasn’t just about more food, but a different kind of food.

The rise in the number of calories provided by the food supply since the 1970s “is more than sufficient to explain the US epidemic of obesity.” Similar spikes in calorie surplus were noted in developed countries around the world in parallel with and presumed to be primarily responsible for, the expanding waistlines of their populations. After taking exports into account, by the year 2000, the United States was producing 3,900 calories for every man, woman, and child—nearly twice as much as many people need.

It wasn’t always this way. The number of calories in the food supply actually declined over the first half of the twentieth century and only started its upward climb to unprecedented heights in the 1970s. The drop in the first half of the century was attributed to the reduction in hard manual labor. The population had decreased energy needs, so they ate decreased energy diets. They didn’t need all the extra calories. But then the “energy balance flipping point” occurred, when the “move less, stay lean phase” that existed throughout most of the century turned into the “eat more, gain weight phase” that plagues us to this day. So, what changed?

As I discuss in my video The Role of Processed Foods in the Obesity Epidemic, what happened in the 1970s was a revolution in the food industry. In the 1960s, most food was prepared and cooked in the home. The typical “married female, not working” spent hours a day cooking and cleaning up after meals. (The “married male, non-working spouse” averaged nine minutes, as you can see below and at 1:34 in my video.) But then a mixed-blessing transformation took place. Technological advances in food preservation and packaging enabled manufacturers to mass prepare and distribute food for ready consumption. The metamorphosis has been compared to what happened a century before with the mass production and supply of manufactured goods during the Industrial Revolution. But this time, they were just mass-producing food. Using new preservatives, artificial flavors, and techniques, such as deep freezing and vacuum packaging, food corporations could take advantage of economies of scale to mass produce “very durable, palatable, and ready-to-consume” edibles that offer “an enormous commercial advantage over fresh and perishable whole or minimally processed foods.”

Think ye of the Twinkie. With enough time and effort, “ambitious cooks” could create a cream-filled cake, but now they are available around every corner for less than a dollar. If every time someone wanted a Twinkie, they had to bake it themselves, they’d probably eat a lot fewer Twinkies. The packaged food sector is now a multitrillion-dollar industry.

Consider the humble potato. We’ve long been a nation of potato eaters, but we usually baked or boiled them. Anyone who’s made fries from scratch knows what a pain it is, with all the peeling, cutting, and splattering of oil. But with sophisticated machinations of mechanization, production became centralized and fries could be shipped at -40°F to any fast-food deep-fat fryer or frozen food section in the country to become “America’s favorite vegetable.” Nearly all the increase in potato consumption in recent decades has been in the form of french fries and potato chips.

Cigarette production offers a compelling parallel. Up until automated rolling machines were invented, cigarettes had to be rolled by hand. It took 50 workers to produce the same number of cigarettes a machine could make in a minute. The price plunged and production leapt into the billions. Cigarette smoking went from being “relatively uncommon” to being almost everywhere. In the 20th century, the average per capita cigarette consumption rose from 54 cigarettes a year to 4,345 cigarettes “just before the first landmark Surgeon General’s Report” in 1964. The average American went from smoking about one cigarette a week to half a pack a day.

Tobacco itself was just as addictive before and after mass marketing. What changed was cheap, easy access. French fries have always been tasty, but they went from being rare, even in restaurants, to being accessible around each and every corner (likely next to the gas station where you can get your Twinkies and cigarettes).

The first Twinkie dates back to 1930, though, and Ore-Ida started selling frozen french fries in the 1950s. There has to be more to the story than just technological innovation, and we’ll explore that next.

This explosion of processed junk was aided and abetted by Big Government at the behest of Big Food, which I explore in my video The Role of Taxpayer Subsidies in the Obesity Epidemic.

This is the fifth video in an 11-part series. Here are the first four:

The Role of Diet vs. Exercise in the Obesity Epidemic The Role of Genes in the Obesity Epidemic The Thrifty Gene Theory: Survival of the FattestCut the Calorie-Rich-And-Processed Foods

Videos still to come are listed in the related videos below.

July 4, 2024

Cutting the Calorie-Rich-And-Processed Foods

We have an uncanny ability to pick out the subtle distinctions in calorie density of foods, but only within the natural range.

The traditional medical view on obesity, as summed up nearly a century ago: “All obese persons are, alike in one fundamental respect,—they literally overeat.” While this may be true in a technical sense, it is in reference to overeating calories, not food. Our primitive urge to overindulge is selective. People don’t tend to lust for lettuce. We have a natural inborn preference for sweet, starchy, or fatty foods because that’s where the calories are concentrated.

Think about hunting and gathering efficiency. We used to have to work hard for our food. Prehistorically, it didn’t make sense to spend all day collecting types of food that on average don’t provide at least a day’s worth of calories. You would have been better off staying back at the cave. So, we evolved to crave foods with the biggest caloric bang for their buck.

If you were able to steadily forage a pound of food an hour and it had 250 calories per pound, it might take you ten hours just to break even on your calories for the day. But if you were gathering something with 500 calories a pound, you could be done in five hours and spend the next five working on your cave paintings. So, the greater the energy density—that is, the more calories per pound—the more efficient the foraging. We developed an acute ability to discriminate foods based on calorie density and to instinctively desire the densest.

If you study the fruit and vegetable preferences of four-year-old children, what they like correlates with calorie density. As you can see in the graph below and at 1:52 in my video Friday Favorites: Cut the Calorie-Rich-And-Processed Foods, they prefer bananas over berries and carrots over cucumbers. Isn’t that just a preference for sweetness? No, they also prefer potatoes over peaches and green beans over melon, just like monkeys prefer avocados over bananas. We appear to have an inborn drive to maximize calories per mouthful.

All the foods the researchers tested in the study with four-year-old kids naturally had less than 500 calories per pound. (Bananas topped the chart at about 400.) Something funny happens when you start going above that: We lose our ability to differentiate. Over the natural range of calorie densities, we have an uncanny aptitude to pick out the subtle distinctions. However, once you start heading towards bacon, cheese, and chocolate territory, which can reach thousands of calories per pound, our perceptions become relatively numb to the differences. It’s no wonder since these foods were unknown to our prehistoric brains. It’s like the dodo bird failing to evolve a fear response because they had no natural predators—and we all know how that turned out—or sea turtle hatchlings crawling in the wrong direction towards artificial light rather than the moon. It is aberrant behavior explained by an “evolutionary mismatch.”

The food industry exploits our innate biological vulnerabilities by stripping crops down into almost pure calories—straight sugar, oil (which is pretty much pure fat), and white flour (which is mostly refined starch). It also removes the fiber, because that effectively has zero calories. Run brown rice through a mill to make white rice, and you lose about two-thirds of the fiber. Turn whole-wheat flour into white flour, and lose 75 percent. Or you can run crops through animals (to make meat, dairy, and eggs) and remove 100 percent of the fiber. What you’re left with is CRAP—an acronym used by one of my favorite dieticians, Jeff Novick, for Calorie-Rich And Processed food.

Calories are condensed in the same way plants are turned into addictive drugs like opiates and cocaine: “distillation, crystallization, concentration, and extraction.” They even appear to activate the same reward pathways in the brain. Put people with “food addiction” in an MRI scanner and show them a picture of a chocolate milkshake, and the areas that light up in their brains (as you can see below and at 4:15 in my video) are the same as when cocaine addicts are shown a video of crack smoking. (See those images below and at 4:18 in my video.)

“Food addiction” is a misnomer. People don’t suffer out-of-control eating behaviors to food in general. We don’t tend to compulsively crave carrots. Milkshakes are packed with sugar and fat, two of the signals to our brain of calorie density. When people are asked to rate different foods in terms of cravings and loss of control, most incriminated was a load of CRAP—highly processed foods like donuts, along with cheese and meat. Those least related to problematic eating behaviors? Fruits and vegetables. Calorie density may be the reason people don’t get up in the middle of the night and binge on broccoli.

Animals don’t tend to get fat when they are eating the foods they were designed to eat. There is a confirmed report of free-living primates becoming obese, but that was a troop of baboons who stumbled across the garbage dump at a tourist lodge. The garbage-feeding animals weighed 50 percent more than their wild-feeding counterparts. Sadly, we can suffer the same mismatched fate and become obese by eating garbage, too. For millions of years, before we learned how to hunt, our biology evolved largely on “leaves, roots, fruits, and nuts.” Maybe it would help if we went back to our roots and cut out the CRAP.

A key insight I want to emphasize here is the concept of animal products as the ultimate processed food. Basically, all nutrition grows from the ground: seeds, sunlight, and soil. That’s where all our vitamins come from, all our minerals, all the protein, all the essential amino acids. The only reason there are essential amino acids in a steak is because the cow ate them all from plants. Those amino acids are essential—no animals can make them, including us. We have to eat plants to get them. But we can cut out the middlemoo and get nutrition directly from the Earth, and, in doing so, get all the phytonutrients and fiber that are lost when plants are processed through animals. Even ultraprocessed junk foods may have a tiny bit of fiber remaining, but all is lost when plants are ultra-ultraprocessed through animals.

Having said that, there was also a big jump in what one would traditionally think of as processed foods, and that’s the video we turn to next: The Role of Processed Foods in the Obesity Epidemic.

We’re making our way through a series on the cause of the obesity epidemic. So far, we’ve looked at exercise (The Role of Diet vs. Exercise in the Obesity Epidemic) and genes (The Role of Genes in the Obesity Epidemic and The Thrifty Gene Theory: Survival of the Fattest), but, really, it’s the food.

If you’re familiar with my work, you know that I recommend eating a variety of whole plant foods, as close as possible to the way nature intended. I capture this in my Daily Dozen, which you can download for free here or get the free app (iTunes and Android). On the app, you’ll see that there’s also an option for those looking to lose weight: my 21 Tweaks. But before you go checking them off, be sure to read about the science behind the checklist in my book How Not to Diet. Get it for free at your local public library. If you choose to buy a copy, note that all proceeds from all of my books go to charity.