Michael Greger's Blog, page 2

August 7, 2025

Is Moringa the Most Nutritious Food?

Does the so-called miracle tree live up to the hype?

Moringa (Moringa oleifera) is a plant commonly known as the “miracle” tree due to its purported healing powers across a spectrum of diseases. If “miracle” isn’t hyperbolic enough for you, “on the Internet,” it’s also known as “God’s Gift to Man.” Is moringa a miracle or just a mirage? “The enthusiasm for the health benefits of M. oleifera is in dire contrast with the scarcity of strong experimental and clinical evidence supporting them. Fortunately, the chasm is slowly being filled.” There has been a surge in scientific publications on moringa. In just the last ten years, the number of articles is closer to a thousand, as shown here and at 1:02 in my video The Benefits of Moringa: Is It the Most Nutritious Food?.

What got my attention was the presence of glucosinolates, compounds that boost our liver’s detoxifying enzymes. I thought they were only found in cruciferous vegetables, such as cabbage, broccoli, kale, collards, and cauliflower. Still, it turns out they’re also present in the moringa family, with a potency comparable to broccoli. But rather than mail-ordering exotic moringa powder, why not just eat broccoli?Is there something special about moringa?

What got my attention was the presence of glucosinolates, compounds that boost our liver’s detoxifying enzymes. I thought they were only found in cruciferous vegetables, such as cabbage, broccoli, kale, collards, and cauliflower. Still, it turns out they’re also present in the moringa family, with a potency comparable to broccoli. But rather than mail-ordering exotic moringa powder, why not just eat broccoli?Is there something special about moringa?

“Moringa oleifera has been described as the most nutritious tree yet discovered,” but who eats trees? Moringa supposedly “contains higher amounts of elemental nutrients than most conventional vegetable sources,” such as featuring 10 times more vitamin A than carrots, 12 times more vitamin C than oranges, 17 times more calcium than milk, 15 times more potassium than bananas, 25 times more iron than spinach, and 9 times more protein than yogurt, as shown here and at 2:08 in my video.  Sounds impressive, but first of all, even if this were true, it is relevant for 100 grams of dry moringa leaf, which is about 14 tablespoons, almost a whole cup of leaf powder. Researchers have had trouble getting people to eat even 20 grams, so anything more would likely “result in excessively unpleasant taste, due to the bitterness of the leaves.”

Sounds impressive, but first of all, even if this were true, it is relevant for 100 grams of dry moringa leaf, which is about 14 tablespoons, almost a whole cup of leaf powder. Researchers have had trouble getting people to eat even 20 grams, so anything more would likely “result in excessively unpleasant taste, due to the bitterness of the leaves.”

Secondly, the nutritional claims in these papers are “adapted from Fuglie,” which is evidently a lay publication. If you go to the nutrient database of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, and enter a more reasonable dose, such as the amount that might be in a smoothie, about a tablespoon, for instance, a serving of moringa powder has as much vitamin A as a quarter of one baby carrot and as much vitamin C as one one-hundredth of an orange. So, an orange has as much vitamin C as a hundred tablespoons of moringa. A serving of moringa powder has the calcium of half a cup of milk, the potassium of not fifteen bananas but a quarter of one banana, the iron of a quarter cup of spinach, and the protein of a third of a container of yogurt, as seen below and at 3:15 in my video. So, it may be nutritious, but not off the charts and certainly not what’s commonly touted. So, again, why not just eat broccoli?

Moringa does seem to have anticancer activity—in a petri dish—against cell lines of breast cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, and fibrosarcoma, while tending to leave normal cells relatively alone, but there haven’t been any clinical studies. What’s the point in finding out that “Moringa oleifera extract enhances sexual performance in stressed rats,” as one study was titled?

Moringa does seem to have anticancer activity—in a petri dish—against cell lines of breast cancer, lung cancer, skin cancer, and fibrosarcoma, while tending to leave normal cells relatively alone, but there haven’t been any clinical studies. What’s the point in finding out that “Moringa oleifera extract enhances sexual performance in stressed rats,” as one study was titled?

Studies like “Effect of supplementation of drumstick (Moringa oleifera) and amaranth (Amaranthus tricolor) leaves powder on antioxidant profile and oxidative status among postmenopausal women” started to make things a little interesting. When researchers were testing the effects of a tablespoon of moringa leaf powder once a day for three months on antioxidant status, they saw a drop in oxidative stress, as one might expect from eating any healthy plant food. However, they also saw a drop in fasting blood sugars from prediabetic levels exceeding 100 to more normal levels. Now, that’s interesting. Should we start recommending a daily tablespoon of moringa powder to people with diabetes, or was it just a fluke? I’ll discuss the study “Moringa oleifera and glycemic [blood sugar] control: A review of the current evidence” next.

August 5, 2025

Are Carboxymethylcellulose, Polysorbate 80, and Other Emulsifiers Safe?

Emulsifiers are the most widely used food additives. What are they doing to our gut microbiome?

When grocery shopping these days, unless you’re sticking to the produce aisle, “it is nearly impossible to avoid processed foods, particularly in the consumption of a typical Western diet,” which is characterized by insufficient plant foods, too much meat, dairy, and eggs, and a lot of processed junk, “along with increased exposure to additives due to their use in processed foods.”

The artificial sweetener sucralose, for example, which is sold as Splenda, “irrefutably disrupts the gut microbiome at doses relevant to human use” and “induces glucose intolerance.” In other words, it can make our blood sugars worse instead of better. It’s relatively easy to avoid artificial sweeteners, but “it may be much more difficult to avoid ingestion of emulsifiers…because they are commonly added to a wide variety of foods within the modern Western diet.” In fact, “emulsifiers are the most widely used additives,” and “most processed foods contain one or more emulsifiers that allow such foods to maintain desired textures and avoid separation into distinct parts (e.g, oil and water layers).” We now consume emulsifiers by the megaton every year, thanks to a multibillion-dollar industry, as you can see below and at 1:03 in my video Are Emulsifiers Like Carboxymethylcellulose and Polysorbate 80 Safe?.

Emulsifiers are commonly found in fatty dressings, breads and other baked goods, mayonnaise and other fatty spreads, candy, and beverages. “Like all authorized food additives, emulsifiers have been evaluated by risk assessors, who consider them safe. However, there are growing concerns among scientists about their possible harmful effects on our intestinal barriers and microbiota,” in terms of causing a leaky gut. As well, they could possibly “increase the absorption of several environmental toxins, including endocrine disruptors and carcinogens” present in the food.

Emulsifiers are commonly found in fatty dressings, breads and other baked goods, mayonnaise and other fatty spreads, candy, and beverages. “Like all authorized food additives, emulsifiers have been evaluated by risk assessors, who consider them safe. However, there are growing concerns among scientists about their possible harmful effects on our intestinal barriers and microbiota,” in terms of causing a leaky gut. As well, they could possibly “increase the absorption of several environmental toxins, including endocrine disruptors and carcinogens” present in the food.

We know that the consumption of ultra-processed foods may contribute to weight gain. Healthier, longer-lived populations not only have low meat intake and high plant intake, but they also eat minimally processed foods and “have far less chronic diseases, obesity rates, and live longer disease-free.” Based on a number of preclinical studies, it may be that the emulsifiers found in processed foods are playing a role, but who cares if “emulsifiers make rats gain weight”? When we read that “emulsifiers can cause striking changes in the microbiota,” they aren’t talking about the microbiota of humans.

Often, mice are used to study the impact on the microbiome, but “only a few percent of the bacterial genes are shared between mice and humans.” Even the gut flora of different strains of mice can be considerably different from each other, so if we can’t even extrapolate from one type of mouse to another, how are we supposed to translate results from mice to humans? “Remarkably, there has been little study of the potential harmful effects of ingested…emulsifiers in humans.”

Take lecithin, for example, which is “perhaps best known as a key component of egg yolks.” Lecithin was found to be worse than polysorbate 80 in terms of allowing bacteria to leak through the gut wall into the bloodstream. However, it’s yet to be determined whether lecithin consumption in humans causes the same problem. “There is certainly a paucity in the data of human trials with the effects of emulsifiers in processed foods,” but we at least have data on human tissue, cells, and gut flora.

A study was titled: “Dietary emulsifiers directly alter the human microbiota composition and gene expression ex vivo potentiating intestinal inflammation.” Ex vivo means outside the body. Researchers inoculated an artificial gut with fresh human feces until a stable culture was established, then added carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) or polysorbate 80 (P80), resulting in boosts in proinflammatory potential starting within one day with the carboxymethylcellulose and within the first week with polysorbate 80, as you can see below and at 3:39 in my video.

“This approach revealed that both P80 and CMC acted directly upon human microbiota to increase its proinflammatory potential…” When researchers then tested the effect of these emulsifiers on the protective mucus layer in petri dish cultures of human gut lining cells, they found that they can partially disrupt the protective layer. As you can see below and at 4:00 in my video, the green staining is the mucus. Both emulsifiers cut down the levels.

However, this study and the last both used emulsifier concentrations that were far in excess of what people might typically get day-to-day.

“Translocation of Crohn’s disease Escherichia coli across M-cells: contrasting effects of soluble plant fibres and emulsifiers” is probably the study that raised the greatest potential concern. The researchers surgically obtained cells, as well as actual intestinal wall tissue, and found that polysorbate 80 could double the invasion of E. coli through the intestinal lining tissue, as shown here and at 4:27 in my video.

In contrast, adding fiber—in this case, fiber from plantains—could seal up the gut wall tissue twice as tightly, as seen below and at 4:33.

In contrast, adding fiber—in this case, fiber from plantains—could seal up the gut wall tissue twice as tightly, as seen below and at 4:33.

July 31, 2025

True Health Intiative: Scientific Consensus on a Healthy Diet

The leading risk factor for death in the United States is the American diet.

About a decade ago, the American Heart Association (AHA) expressed concern that its “2020 target of improving cardiovascular health by 20% by 2020 will not be reached if current trends continue.” By 2006, most people were already not smoking and had nearly achieved their goal for exercise. But when it came to healthy diet score, only about 1 percent got a 4 or 5 out of its diet quality score of 0 to 5, as you can see below and at 0:35 in my video, Friday Favorites: The Scientific Consensus on a Healthy Diet. And that’s with such “ideal” criteria as drinking less than four and a half cups of soda a week.

In the last decade, the AHA saw a bump in the prevalence of the ideal healthy diet score to about 1 percent of Americans reaching those kinds of basic criteria, but, given its “aggressive” goal of reaching a “20% target” by 2020, it hoped to turn that 1 percent into about 1.2 percent. (Really, as you can see here and at 1:01 in my video.)

So, how’d we do? According to the 2019 update, it seems we’ve slipped down to as low as one in a thousand, and American teens scored a big fat zero. No wonder, perhaps, that “for all mortality-based metrics, the US rank declined…to 27th or 28th among 34 OECD [industrialized] countries. Citizens living in countries with a substantially lower gross domestic product and health expenditure per capita…have lower mortality rates than those in the United States.” Slovenia, for example, beat the United States, ranking 24th in life expectancy. More recently, the United States’s life expectancy slipped further, down to 43rd in the world, although the United States spent the most ($3.0 trillion) on health care…”

What is the leading risk factor for death in the United States? As seen below and at 2:04 in my video, it is the standard American diet. Those trillions in health care spending aren’t addressing the root cause of disease, disability, and death.

Here are some of the lung cancer death curves, below and at 2:08 in my video:

It took decades to finally turn the corner, but it’s so nice to finally see those drops. When will we see the same with diet?

“Approximately 80% of chronic disease and premature death could be prevented by not smoking, being physically active, and adhering to a healthful dietary pattern.” What exactly is meant by “healthy diet”? “Unfortunately, media messages surrounding nutrition are often inconsistent, confusing, and do not enable the public to make positive changes in health behaviors….Certainly, there is pressure within today’s competitive journalism market for sensationalism. There may even be a disincentive to present the facts in the context of the total body of information consumers need to act on dietary recommendations.” And there’s an incentive to sell more magazines and newspapers. The paper I’m quoting was written in 1997, before the lure of clickbait headlines. In fact, about three-quarters of a century ago, it was noted: “It is unfortunate that the subject of nutrition seems to have a special appeal to the credulous, the social zealot and, in the commercial field, the unscrupulous….The combination is one calculated to strike despair in the hearts of the sober, objective scientist.”

Indeed, the most important health care problem we face may be “our poor lifestyle choices based on misinformation.” It is like the climate change deniers: “Analogous to outspoken cynics denying climate change and influencing public opinion, healthy lifestyle and dietary advice are overshadowed by critics, diet books, the food industry, and misguided information in the media.” Maybe we need an entity like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—but for nutrition.

These days, “no single expert, regardless of academic stature or reputation, has the prominence to overcome the obstacles created by confusing media messages and deliver the fundamental principles of healthy living effectively to the public.”

What if there were “a global coalition consisting of a variety of nutrition experts, who collectively represent the views held by the majority of scientists, physicians, and health practitioners” that could “serve as the guiding resource of sound nutrition information for improved health and prevention of disease”?

Enter the True Health Initiative, which “was conceived for that very purpose.” A nonprofit coalition of hundreds of experts from dozens of countries has agreed to a consensus statement on the fundamentals of healthy living. See www.truehealthinitiative.org.

Spoiler alert: The healthiest diet is one generally comprised mostly of minimally processed plants.

July 29, 2025

Cleaning Products, Air Fresheners, and Lung Function

There is a reason the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention prohibits not only smoking but also scented or fragranced products in its buildings.

In a recent review entitled “Damaging Effects of Household Cleaning Products on the Lungs,” researchers noted: “Adverse respiratory effects of cleaning products were first observed in populations experiencing high levels of exposure at the workplace, such as cleaners and health-care workers, with a primary focus on asthma.” Occupational use of disinfectants has also been linked to a higher risk of developing chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, such as emphysema.

As I discuss in my video Friday Favorites: The Effects of Cleaning Products and Air Fresheners on Lung Function, we now know that, in addition to workplace exposures, “exposure to household cleaning products has also emerged as a risk factor for respiratory disorders in childhood,” as well potentially being “an important risk factor for adult asthma.” Common household cleaning spray use accounts for as many as one in seven adult asthma cases. The thought is that inhaling chemical irritants may cause injury to the airways, leading to oxidative stress and inflammation. What can we do about it?

Well, it may be limited to sprays. Researchers found that cleaning products that were not sprayed were not associated with asthma. It’s also possible that environmentally friendly cleaning products “may represent a safer alternative,” though they may still present some risk.

Ideally, safer cleaning products should be available. Unfortunately, the research suggesting harm has “seldom been heeded by manufacturers, vendors, and commercial cleaning companies.” I wonder how much of that is because “most of the workers exposed to cleaning products are women”—both occupationally and, perhaps, domestically.

One of the problems may be the fragrance chemicals. One in three Americans surveyed “reported health problems, such as migraine headaches and respiratory difficulties, when exposed to fragranced products.” And, for about half of them, the problems were so bad they actually lost work over it, either “workdays or a job due to fragranced product exposure in the workplace.”

“Results from this study reveal that over one-third of Americans suffer adverse health effects, such as respiratory difficulties and migraine headaches, from exposure to fragranced products. Of those individuals, half reported that the effects can be disabling. Yet over 99% of Americans are exposed to fragranced products at least once a week, from their own or others’ use.”

The effect on asthmatics may be even worse, affecting closer to two-thirds of Americans. One compound that may be of particular concern is called 1,4-dichlorobenzene, also known as para-dichlorobenzene, which is found in many air fresheners, toilet bowl deodorants, and mothballs. It breaks down in the body into a compound called 2,5-dichlorophenol, which we pee out, giving researchers a reliable measure of our dichlorobenzene exposure. Not only may it make respiratory problems worse for those already suffering from compromised airways, but exposure to dichlorobenzene “at [blood] levels found in the U.S. general population, may result in reduced pulmonary [lung] function” in people who start out with normal breathing. What’s worse, higher exposures “were associated with greater prevalence of CVD [cardiovascular disease] and all cancers combined,” another reason to avoid it. We’d better read labels, right?

Surprisingly, “no law in the US requires the disclosure of all ingredients in fragranced consumer products.” In fact, for laundry supplies, cleaning products, and air fresheners, manufacturers “do not need to list the presence of a ‘fragrance’ on either the label or MSDS,” the material safety data sheet. We won’t know until we smell it.

I support the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s ban. Not only is “the use of tobacco products (including cigarettes, cigars, pipes, smokeless tobacco, or other tobacco products)…prohibited at all times,” but “scented or fragranced products are prohibited at all times in all interior space owned, rented, or leased by CDC.” I wish rideshare services like Uber and Lyft would have a similar policy. I’d even be happy with just a fragrance-free option. About one in five of more than a thousand Americans surveyed said they “would enter a business but then leave as quickly as possible if they smelled air fresheners or some fragranced product,” so it’s in the best interest of businesses, too. “Over 50% of the population would prefer that workplaces, health care facilities and professionals, hotels, and airplanes were fragrance-free.”

July 24, 2025

Boosting BDNF Levels in Our Brain to Treat Depression

We can raise BDNF levels in our brain by fasting and exercising, as well as by eating and avoiding certain foods.

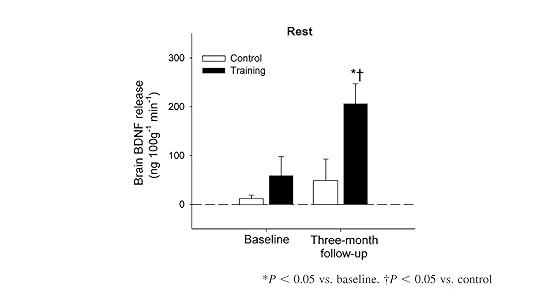

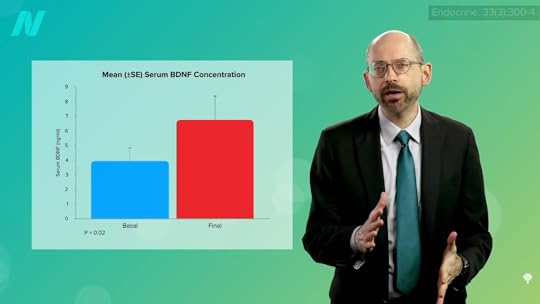

There is accumulating evidence that brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) may be playing a role in human depression. BDNF controls the growth of new nerve cells. “So, low levels of this peptide could lead to an atrophy of specific brain areas such as the amygdala and the hippocampus, as it has been observed among depressed patients.” That may be one of the reasons that exercise is so good for our brains. Start an hour-a-day exercise regimen, and, within three months, there can be a quadrupling of BDNF release from our brain, as seen below and at 0:35 in my video How to Boost Brain BDNF Levels for Depression Treatment.

This makes sense. Any time we were desperate to catch prey (or desperate not to become prey ourselves), we needed to be cognitively sharp. So, when we’re fasting, exercising, or in a negative calorie balance, our brain starts churning out BDNF to make sure we’re firing on all cylinders. Of course, Big Pharma is eager to create drugs to mimic this effect, but is there any way to boost BDNF naturally? Yes, I just said it: fasting and exercising. Is there anything we can add to our diet to boost BDNF?

Higher intakes of dietary flavonoids appear to be protectively associated with symptoms of depression. The Harvard Nurses’ Health Study followed tens of thousands of women for years and found that those who were consuming the most flavonoids appeared to reduce their risk of becoming depressed. Flavonoids occur naturally in plants, so there’s a substantial amount in a variety of healthy foods. But how do we know the benefits are from the flavonoids and not just from eating more healthfully in general? We put it to the test.

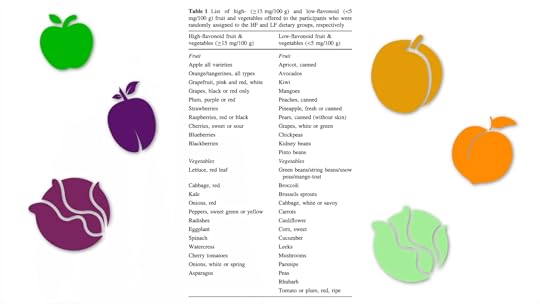

Some fruits and vegetables have more flavonoids than others. As shown below and at 1:51 in my video, apples have more than apricots, plums more than peaches, red cabbage more than white, and kale more than cucumbers. Researchers randomized people into one of three groups: more high-flavonoid fruits and vegetables, more low-flavonoid fruits and vegetables, or no extra fruits and vegetables at all. After 18 weeks, only the high-flavonoid group got a significant boost in BDNF levels, which corresponded with an improvement in cognitive performance. The BDNF boost may help explain why each additional daily serving of fruits or vegetables is associated with a 3 percent decrease in the risk of depression.

What’s more, as seen here and at 2:27 in my video, a teaspoon a day of the spice turmeric may boost BNDF levels by more than 50 percent within a month. This is consistent with the other randomized controlled trials that have so far been done.

Nuts may help, too. In the PREDIMED study, where people were randomized to receive weekly batches of nuts or extra-virgin olive oil, the nut group lowered their risk of having low BDNF levels by 78 percent, as shown below and at 2:46.

And BDNF is not implicated only in depression, but schizophrenia. When individuals with schizophrenia underwent a 12-week exercise program, they got a significant boost in their BDNF levels, which led the researchers to “suggest that exercise-induced modulation of BDNF may play an important role in developing non-pharmacological treatment for chronic schizophrenic patients.”

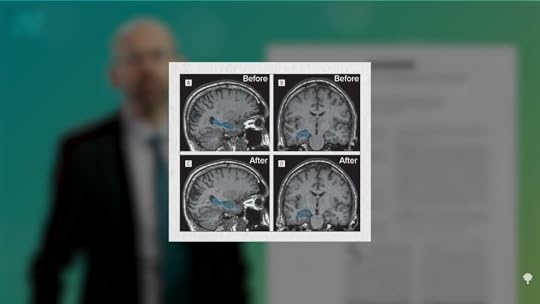

What about schizophrenia symptoms? Thirty individuals with schizophrenia were randomized to ramp up to 40 minutes of aerobic exercise three times a week or not, and there did appear to be an improvement in psychiatric symptoms, such as hallucinations, as well as an increase in their quality of life, with exercise. In fact, researchers could actually visualize what happened in their brains. Loss of brain volume in a certain region appears to be a feature of schizophrenia, but 30 minutes of exercise, three times a week, resulted in an increase of up to 20 percent in the size of that region within three months, as seen here and at 3:46 in my video.

Caloric restriction may also increase BDNF levels in people with schizophrenia. So, researchers didn’t just have study participants eat less, but more healthfully, too—less saturated fat and sugar, and more fruits and veggies. The study was like the Soviet fasting trials for schizophrenia that reported truly unbelievable results, supposedly restoring people to function, and described fasting as “an unparalleled achievement in the treatment of schizophrenia”—but part of the problem is that the diagnostic system the Soviets used is completely different than ours, making any results hard to interpret. There was a subgroup that seemed to correspond to the Western definition, but they still reported 40 to 60 percent improvement rates from fasting, but fasting wasn’t all they did. After the participants fasted for up to a month, they were put on a meat- and egg-free diet. So, when the researchers reported these remarkable effects even years later, they were for those individuals who stuck with the meat- and egg-free diet. Evidently, the closer the diet was followed, the better the effect, and those who broke the diet relapsed. The researchers noted: “Not all patients can remain vegetarian, but they must not take meat for at least six months, and then in very small portions.” We know from randomized controlled trials that simply eschewing meat and eggs can improve mental states within just two weeks, so it’s hard to know what role fasting itself played in the reported improvements.

A single high-fat meal can drop BDNF levels within hours of consumption, and we can prove it’s the fat itself by seeing the same result after injecting fat straight into our veins. Perhaps that helps explain why increased consumption of saturated fats in a high-fat diet may contribute to brain dysfunction—that is, neurodegenerative diseases, long-term memory loss, and cognitive impairment. It may also help explain why the standard American diet has been linked to a higher risk of depression, as dietary factors modulate the levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor.

July 22, 2025

Does Fasting Help Treat Depression?

Caloric restriction can boost levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is considered to play a critical role in mood disorders.

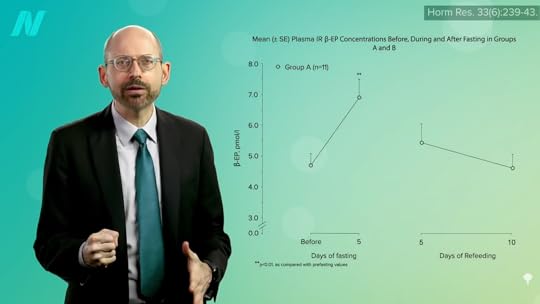

For more than a century, fasting has been espoused as a treatment of supposed “great utility in the preservation of health,” especially rejuvenating the body and, above all, the mind. When people fast for even 18 hours, though, they may get hungry and irritable. After one or two days, positive mood goes down and negative mood goes up, and after three days, fasters can increasingly feel sad, self-blame, and suffer a loss of libido. Then, something strange starts to happen: People experience a “fasting-induced mood enhancement…reflected by decreased anxiety, depression, fatigue, and improved vigor.” Studies tend to show this across the board. Once you get over the hump, fasters frequently experience “an increased level of vigilance and a mood improvement, a subjective feeling of well-being, and sometimes of euphoria.” And, no wonder, as, by then, endorphin levels may rise by nearly 50 percent, as seen here and at 1:06 in my video Friday Favorites: Fasting to Treat Depression.

This enhancement of mood, alertness, and calm makes a certain amount of evolutionary sense. Our body wants us to feel poorly initially so we continue to eat, day to day, when food is available, but if we go a couple of days without food, our body realizes we can’t just mope in our cave; we need to get motivated to go out and find some calories.

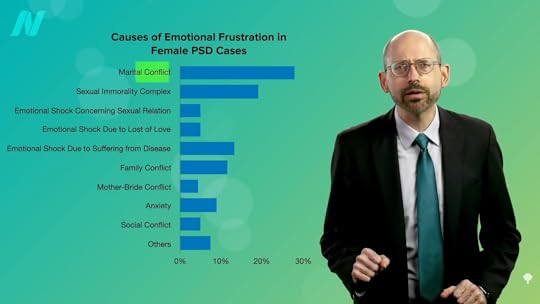

So, can fasting be used for mood disorders, like depression? It’s great that people can feel better after a few days of fasting, but the critical question revolves around the “persistence of mood improvement over time” once fasting ends and eating resumes. The little published evidence we have comes out of Japan and the former Soviet Union, and some of it is just ridiculous, like this study that included women with a variety of symptoms, which the researchers blame mostly on marital conflict, as you can see below and at 2:08 in my video. Husband not treating you right? How about some “electroshock therapy”? That didn’t seem to help much, so what about “hunger therapy”? Of course, starving the women made them hungry, but that’s what Thorazine is for. If they keep getting injected with an antipsychotic to calm them down, they can sail right through. So, what happened in the study? What would we even do with those results?

Another study, however, skipped the Thorazine. The participants fasted for ten days, but they were also kept in bed all day on “absolute bed rest,” completely isolated and “prohibited from seeing other people except the attending doctor and nurse…also denied access to television, radio, newspapers or any other forms of information.” So, if people got better or worse, it would be impossible to tease out the effects of the fasting component on its own. But researchers found that they apparently did get better, with efficacy reportedly demonstrated in 31 out of 36 patients suffering from depression, as seen here and at 2:56 in my video.

The researchers concluded that fasting therapy may provide an alternative to the use of antidepressant drugs, “thinking the fasting therapy may be a kind of shock therapy.” People are so relieved to be eating again, to get out of solitary confinement, and to even just get out of bed that they report feeling better. That was at the time of discharge, though. How did they feel the next day, the next week, the next month? Fasting is, by definition, unsustainable, so what we want to ideally see are some kind of longer-lasting effects.

Researchers did a follow-up with a few hundred patients, not just a few months later, but after a few years. Of the 69 who were evidently suffering from depression, 90 percent reported feeling good or excellent results at the end of the ten-day fast, and, remarkably, years later, 87 percent of the 62 individuals who replied claimed that they were still doing well. Now, there was no control group, so we don’t know if they would have done just as well or even better without the fast, and it was all self-reporting, so there may have been a response bias where participants tried to please the researchers. Who knows? Maybe they were afraid they’d get sent back to solitary if they didn’t respond affirmatively. We have no idea, but we do have good evidence for the short-term mood benefits.

Why would fasting improve feelings of depression? In addition to the endorphins and the surge in serotonin, the so-called happiness hormone, when we fast, there is a bump in brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which is considered to play a crucial role in mood disorders. Researchers have perked up rodents with it, but we aren’t rats or mice. What about us? Humans with major depression have lower levels of BDNF circulating in their bloodstream. Autopsy studies of suicide victims show only about half the BDNF in certain key brain regions, compared to controls, suggesting it may play an important role in suicidal behavior, as seen here and at 4:38 in my video.

We can boost BDNF with antidepressant drugs and electroshock; we can also boost it with caloric restriction. We can get a 70 percent boost in levels after three months of cutting 25 percent of calories out of our daily diet, as shown below and at 4:51.

Is there anything we can add to our diets to boost BNDF levels so we can get the benefits without the hunger? We’ll find out next.

July 17, 2025

IBD and Cannabis

Smoking cannabis may help with symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the short term, but it may make the long-term prognosis worse.

As this study asks, “Medical Marijuana: A Panacea or Scourge?” For 5,000 years, cannabis “has been used throughout the world medically, recreationally, and spiritually.” It was even prescribed by American physicians “for a plethora of indications” from the mid-19th century to the 1930s, a fact that’s often used by medical marijuana proponents as evidence justifying the modern medical applications.” But the field of old-timey medicine is “fraught with potions and herbal remedies,” not to mention bloodletting and other questionable and harmful remedies.

Skeptics criticize the medical marijuana movement as the “‘medical excuse marijuana’ movement,” insinuating that children with epilepsy and the terminally ill are being “used as a ‘Trojan horse’ for the legalization of recreational cannabis use” or to peddle “outlandish claims” about “miracle cancer cures,” frustrating researchers in the field who just want to get at the science.

For example, what about the therapeutic use of cannabis for inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis? Conventional therapies work mainly by suppressing the immune system to try to tamp down inflammation. “Given the limited therapy options and known adverse side effects with chronic use” from these drugs, people suffering from these diseases often need to have inflamed sections of their bowels removed surgically, so it’s clear why there’s so much interest in alternative approaches.

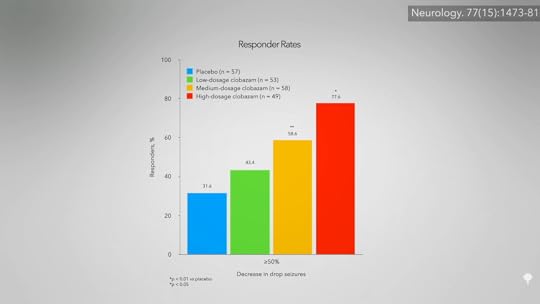

About one in six IBD patients who use marijuana say it helps with their symptoms, so researchers decided to put it to the test. Thirteen patients with IBD were given a third of a pound of marijuana to smoke at their leisure over a period of three months, and they reported feeling significantly better with “reported improvement in general health perception, social functioning, ability to work, physical pain, and depression.” There wasn’t a control group, so it’s unknown if they would have improved anyway or what role the placebo effect may have played. It’s like some of the studies of cannabis used for pediatric epilepsy that had response rates exceeding 30 percent and a frequency cut in half in a third of the kids. Amazing results until you realize you can sometimes get similarly amazing responses from giving kids nothing but a sugar pill placebo, as seen below and at 2:21 in my video Friday Favorites: Cannabis for Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD). That’s why it’s critical to do randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, but there weren’t any on cannabis and IBD until 2013.

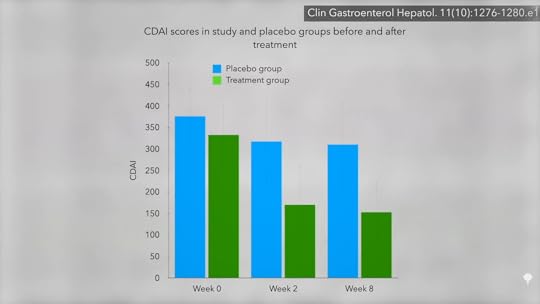

For 21 patients with Crohn’s disease, nothing seemed to help. So researchers randomized them to either smoke two joints a day of marijuana or a look-alike placebo. The results? Ninety percent of those in the cannabis group got better, compared to only 40 percent in the placebo group. Shown below and at 3:11 in my video is a graph of their symptom scores. As you can see, there was no big change in the placebo group over the two-month study, but the cannabis group cut their symptoms by about half.

The researchers acknowledge that long-term cannabis use is not without risks, but it may be a cakewalk compared to the potential adverse—and even life-threatening—side effects of some of the more powerful conventional therapies, so the study was heralded in a paper entitled “High Hope for Medical Marijuana in Digestive Disorders.”

The study was funded by a medical marijuana advocacy organization, the main supplier in the country, in fact. So, expectations may have been placed on the participants about how much better they would feel—in other words, they may have been primed for the placebo effect. But the researchers controlled for that, right? Those getting the real cannabis did significantly better than those randomized to get the placebo. But the point of a placebo is that it is indistinguishable from the real thing, so the participants don’t know which group they’re in—the control group or the treatment group. How can that be accomplished with a psychoactive drug? It can’t, which is the problem. The researchers tried to hide which group participants were in by only recruiting patients who had never tried cannabis before in the hopes that they wouldn’t notice placebo pot, but, unsurprisingly, most of them did. So, we’re basically left with another unblinded study. The researchers asked a bunch of subjective questions, like “How are you feeling?” and those who pretty much knew they were taking the drug said they were feeling better.

There were no significant changes in objective lab values, like CRP, a sign of inflammation, so perhaps the “cannabis may simply be masking symptoms without affecting intestinal inflammation.” Another indicator that it may not be affecting the course of the disease itself is how quickly the symptoms rebound. Two weeks after the study ended, those in the cannabis group were right back to where they started, as shown here (see week 10) and at 5:05 in my video.

So, “there was no difference in objective inflammatory markers to indicate disease modification. Given the rapid rebound…to pretreatment levels after the 2-week washout period, it seems more plausible that cannabis ameliorated the symptoms of Crohn’s disease, rather than actually modulating the disease.” That may be, but the symptoms are terrible. A reduction in pain is a reduction in pain. Indeed, “from the point of view of the patients, a marked symptomatic improvement and ability to resume normal life is not trivial, even if inflammation persists.” Of course, what if cannabis somehow makes the disease worse in the long run?

A survey study published the following year found that cannabis provided the same immediate symptomatic relief but was associated with a worse disease prognosis over time. Patients with IBD reported that cannabis improved their pain, cramping, and diarrhea, but use for more than six months by Crohn’s patients appeared to be a strong predictor of them ending up in surgery; they had five times the odds of going under the knife. There are two possible explanations for this: It’s quite possible that the increased disease severity led to the cannabis use and not the other way around. The alternative explanation: “Cannabis use may worsen the prognosis of IBD, leading to greater surgeries and hospitalizations.”

This is why we need prospective clinical trials where people are followed over time to see which came first. Until then, perhaps we should consider cannabis use for IBD as “potentially harmful.” Not just to err on the side of caution, but because there was a study on hepatitis C patients that found that daily cannabis use was associated with nearly seven times the odds of worse liver fibrosis, which is like scar tissue. If cannabis really does make fibrosis worse, that may explain why cannabis users with IBD may be more likely to require surgery.

July 15, 2025

Eating to Downregulate a Gene for Metastatic Cancer

Women with breast cancer should include the “liberal culinary use of cruciferous vegetables.”

Both the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study and the Women’s Health Initiative study showed that women randomized to a lower-fat diet enjoyed improved breast cancer survival. However, in the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study, women with breast cancer were also randomized to drop their fat intake down to 15 to 20 percent of calories, yet there was no difference in breast cancer relapse or death after seven years.

Any time there’s an unexpected result, you must question whether the participants actually followed through with study instructions. For instance, if you randomized people to stop smoking and they ended up with the same lung cancer rates as those in the group who weren’t instructed to quit, one likely explanation is that the group told to stop smoking didn’t actually stop. In the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living Study, both the dietary intervention group and the control group started out at about 30 percent of calories from fat. Then, the diet group was told to lower their fat intake to 15 to 20 percent of calories. By the end of the study, they had in fact gone from 28.5 percent fat to 28.9 percent fat, as you can see below and at 1:16 in my video The Food That Can Downregulate a Metastatic Cancer Gene. They didn’t even reduce their fat intake. No wonder they didn’t experience any breast cancer benefit.

When you put together all the trials on the effect of lower-fat diets on breast cancer survival, even including that flawed study, you see a reduced risk of breast cancer relapse and a reduced risk of death. In conclusion, going on a low-fat diet after a breast cancer diagnosis “can improve breast cancer survival by reducing the risk of recurrence.” We may now know why: by targeting metastasis-initiating cancer cells through the fat receptor CD36.

We know that the cancer-spreading receptor is upregulated by saturated fat. Is there anything in our diet that can downregulate it? Broccoli.

Broccoli appears to decrease CD36 expression by as much as 35 percent (in mice). Of all fruits and vegetables, cruciferous vegetables like broccoli were the only ones associated with significantly less total risk of cancer and not just getting cancer in the first place, as you can see here and at 2:19 in my video.

Those with bladder cancer who eat broccoli also appear to live longer than those who don’t, and those with lung cancer who eat more cruciferous veggies appear to survive longer, too.

For example, as you can see below and at 2:45 in my video, one year out, about 75 percent of lung cancer patients eating more than one serving of cruciferous vegetables a day were still alive (the top line in red), whereas, by then, most who had been getting less than half a serving a day had already died from their cancer (the bottom line in green).

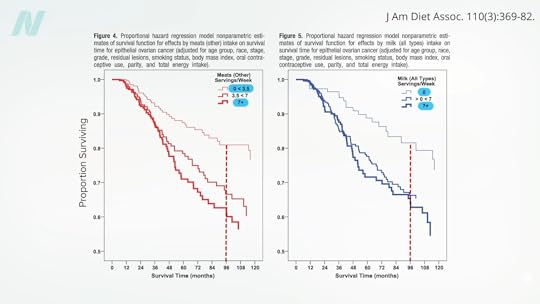

Ovarian cancer, too. Intake of cruciferous vegetables “significantly favored survival,” whereas “a survival disadvantage was shown for meats.” Milk also appeared to double the risk of dying. Below and at 3:21 in my video are the survival graphs. Eight years out, about 40 percent of ovarian cancer patients who averaged meat or milk every day were deceased (the boldest line, on the bottom), compared to only about 20 percent who had meat or milk only a few times a week at most (the faintest line, on the top).

Now, it could be that the fat and cholesterol in meat increased circulating estrogen levels, or it could be because of meat’s growth hormones or all its carcinogens. And galactose, the sugar naturally found in milk, may be directly toxic to the ovary. Dairy has all its hormones, too. However, the lowering of risk with broccoli and the increasing of risk with meat and dairy are also consistent with the CD36 mechanism of cancer spread.

Researchers put it to the test in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer who were given pulverized broccoli sprouts or a placebo. The average death rate was lower in the broccoli sprout group compared to the placebo group. After a month, 18 percent of the placebo group had died, but none in the broccoli group. By three months, another 25 percent of the placebo group had died, but still not a single death in the broccoli group. And by six months, 43 percent of the remaining patients in the placebo group were deceased, along with the first 25 percent of the broccoli group. Unfortunately, even though the capsules for both groups looked the same, “true blinding was not possible,” and the patients knew which group they were in “because the pulverized broccoli sprouts could be easily distinguished from the methylcellulose [placebo] through their characteristic smell and taste.” So, we can’t discount the placebo effect. What’s more, the study participants weren’t properly randomized “because many of the patients refused to participate unless they were placed into the [active] treatment group.” That’s understandable, but it makes for a less rigorous result. A little broccoli can’t hurt, though, and it may help. It’s the lack of downsides of broccoli consumption that leads to “Advising Women Undergoing Treatment for Breast Cancer” to include the “liberal culinary use of cruciferous vegetables,” for example.

It’s the same for reducing saturated fat. The title of an editorial in a journal of the National Cancer Institute asked: “Is It Time to Give Breast Cancer Patients a Prescription for a Low-Fat Diet?” “Although counseling women to consume a healthy diet after breast cancer diagnosis is certainly warranted for general health, the existing data still fall a bit short of proving this will help reduce the risk of breast cancer recurrence and mortality.” But what do we have to lose? After all, it’s still certainly warranted for general health.

July 10, 2025

Eating to Help Control Cancer Metastasis

Randomized controlled trials show that lowering saturated fat intake can lead to improved breast cancer survival.

The leading cause of cancer-related death is metastasis. Cancer kills because cancer spreads. The five-year survival rate for women with localized breast cancer is nearly 99 percent, for example, but that falls to only 27 percent in women with metastasized cancer. Yet, “our ability to effectively treat metastatic disease has not changed significantly in the past few decades…” The desperation is evident when there are such papers as “Targeting Metastasis with Snake Toxins: Molecular Mechanisms.”

We have built-in defenses, natural killer cells that roam the body, killing off budding tumors. But, as I’ve discussed, there’s a fat receptor called CD36 that appears to be essential for cancer cells to spread, and these cancer cells respond to dietary fat intake, but not all fat.

CD36 is upregulated by palmitic acid, as much as a 50-fold increase within 12 hours of consumption, as shown below and at 1:13 in my video How to Help Control Cancer Metastasis with Diet.

Palmitic acid is a saturated fat made from palm oil that can be found in junk food, but it is most concentrated in meat and dairy. This may explain why, when looking at breast cancer mortality and dietary fat, “there was no difference in risk of breast-cancer-specific death…for women in the highest versus the lowest category of total fat intake,” but there’s about a 50 percent greater likelihood of dying of breast cancer with higher intake of saturated fat. Researchers conclude: “These meta-analyses have shown that saturated fat intake negatively impacts breast cancer survival.”

This may also explain why “intake of high-fat dairy, but not low-fat dairy, was related to a higher risk of mortality after breast cancer diagnosis.” If a protein in dairy, like casein, was the problem, skim milk might be even worse, but that wasn’t the case. It’s the saturated butterfat, perhaps because it triggered that cancer-spreading mechanism induced by CD36. Women who consumed one or more daily servings of high-fat dairy had about a 50 percent higher risk of dying from breast cancer.

We see the same with dairy and its relationship to prostate cancer survival. Researchers found that “drinking high-fat milk increased the risk of dying from prostate cancer by as much as 600% in patients with localized prostate cancer. Low-fat milk was not associated with such an increase in risk.” So, it seems to be the animal fat, rather than the animal protein, and these findings are consistent with analyses from the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS) and the Physicians’ Health Study (PHS), conducted by Harvard researchers.

There is even more evidence that the fat receptor CD36 is involved. The “risk of colorectal cancer for meat consumption” increased from a doubling to an octupling—that is, the odds of getting cancer multiplied eightfold for those who carry a specific type of CD36 gene. So, “Is It Time to Give Breast Cancer Patients a Prescription for a Low-Fat Diet?” A cancer diagnosis is often referred to as a ‘teachable moment’ when patients are motivated to make changes to their lifestyle, and so provision of evidence-based guidelines is essential.”

In a randomized, prospective, multicenter clinical trial, researchers set out “to test the effect of a dietary intervention designed to reduce fat intake in women with resected, early-stage breast cancer,” meaning the women had had their breast cancer surgically removed. As shown below and at 4:02 in my video, the study participants in the dietary intervention group dropped their fat intake from about 30 percent of calories down to 20 percent, reduced their saturated fat intake by about 40 percent, and maintained it for five years. “After approximately 5 years of follow-up, women in the dietary intervention group had a 24% lower risk of relapse”—a 24-percent lower risk of the cancer coming back—“than those in the control group.”

That was the WINS study, the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. Then there was the Women’s Health Initiative study, where, again, women were randomized to lower their fat intake down to 20 percent of calories, and, again, “those randomized to a low-fat dietary pattern had increased breast cancer overall survival. Meaning: A dietary change may be able to influence breast cancer outcome.” What’s more, not only was their breast cancer survival significantly greater, but the women also experienced a reduction in heart disease and a reduction in diabetes.

July 8, 2025

Dietary Components That May Cause Cancer to Metastasize

Palmitic acid, a saturated fat concentrated in meat and dairy, can boost the metastatic potential of cancer cells through the fat receptor CD36.

The leading cause of death in cancer patients is metastasis formation. That’s how most people die of cancer—not from the primary tumor, but the cancer spreading through the body. “It is estimated that metastasis is responsible for ~90% of cancer deaths,” and little progress has been made in stopping the spread, despite our modern medical armamentarium. In fact, we can sometimes make matters worse. In an editorial entitled “Therapy-Induced Metastasis,” its authors “provide evidence that all the common therapies, including radiotherapy, chemotherapy, fine needle biopsies, surgical procedures and anaesthesia, have the potential to contribute to tumour progression.” You can imagine how cutting around a tumor and severing blood vessels might lead to the “migration of residual tumour cells,” but why chemotherapy? How might chemo exacerbate metastases? “Despite reducing the size of primary tumors, chemotherapy changes the tumor microenvironment”—its surrounding tissues—“resulting in an increased escape of cancer cells into the blood stream.” Sometimes, chemo, surgery, and radiation are entirely justified, but, again, other times, these treatments can make matters worse. If only we had a way to treat the cause of the cancer’s spreading.

The development of antimetastatic therapies has been hampered by the fact that the cells that initiate metastasis remain unidentified. Then, a landmark study was published: “Targeting Metastasis-Initiating Cells Through the Fatty Acid Receptor CD36.” Researchers found a subpopulation of human cancer cells “unique in their ability to initiate metastasis”; they all express high levels of a fat receptor known as CD36, dubbed “the fat controller.” It turns out that palmitic acid or a high-fat diet specifically boosts the metastatic potential of these cancer cells. Where is palmitic acid found? Although it was originally discovered in palm oil, palmitic acid is most concentrated in meat and dairy. “Emerging evidence shows that palmitic acid (PA), a common fatty acid in the human diet, serves as a signaling molecule regulating the progression and development of many diseases at the molecular level.” It is the saturated fat that is recognized by CD36 receptors on cancer cells, and we know it is to blame, because if the CD36 receptor is blocked, so are metastases.

The study was of a human cancer, but it was a human cancer implanted into mice. However, clinically (meaning in cancer patients themselves), the presence of these CD36-studded metastasis-initiating cells does indeed correlate with a poor prognosis. CD36 appears to drive the progression of brain tumors, for example. As seen in the survival curves shown below and at 3:21 in my video What Causes Cancer to Metastasize?, those with tumors with less CD36 expression lived significantly longer. It is the same with breast cancer mortality: “In this study, we correlated the mortality of breast cancer patients to tumor CD36 expression levels.” That isn’t a surprise, since “CD36 plays a critical role in proliferation, migration and…growth of…breast cancer cells.” If we inhibit CD36, we can inhibit “the migration and invasion of the breast cancer cells.”

Below and at 3:46 in my video, you can see breast cancer cell migration and invasion, before and after CD36 inhibition. (The top lines with circles are before CD36 inhibition, and the bottom lines with squares are after.)

This isn’t only in “human melanoma- and breast cancer–derived tumours” either. Now we suspect that “CD36 expression drives ovarian cancer progression and metastasis,” too, since we can inhibit ovarian cancer cell invasion and migration, as well as block both lymph node and blood-borne metastasis, by blocking CD36. We also see the same kind of effect with prostate cancer; suppress the uptake of fat by prostate cancer cells and suppress the tumor. This was all studied with receptor-blocking drugs and antibodies in a laboratory setting, though. If these “metastasis-initiating cancer cells particularly rely on dietary lipids [fat] to promote metastasis,” the spread of cancer, why not just block the dietary fat in the first place?

“Lipid metabolism fuels cancer’s spread.” Cancer cells love fat and cholesterol. The reason is that so much energy is stored in fat. “Hence, CD36+ metastatic cells might take advantage of this feature to obtain the high amount of energy that is likely to be required for them to anchor and survive at sites distant from the primary tumour”—to set up shop throughout the body.

“The time when glucose [sugar] was considered as the major, if not only, fuel to support cancer cell proliferation is over.” There appears to be “a fatter way to metastasize.” No wonder high-fat diets (HFD) may “play a crucial role in increasing the risk of different cancer types, and a number of clinical studies have linked HFD with several advanced cancers.”

If dietary fat may be “greasing the wheels of the cancer machine,” might there be “specific dietary regimens” we could use to starve cancers of dietary fat? You don’t know until you put it to the test, which we’ll look at next.