Michael Greger's Blog, page 5

April 29, 2025

Gaming the System: Cardiologists, Heart Stents, and Upcoding

Cardiologists can criminally game the system by telling patients they have much more serious, unstable diseases than they really have—fraud that results in unnecessary procedures, unnecessary costs, and unnecessary patient harm.

“The history of medicine abounds with dogmas assumed and later overcome”—sometimes, much later. The Women’s Health Initiative study showed that giving women Premarin, a hormone replacement therapy, increased the risk of the number one killer of women, heart disease, as well as breast cancer risk. Millions of women stopped taking it, and breast cancer rates came down.

Another such reversal of an established medical practice is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—angioplasty and stents for stable coronary artery disease. Billions of dollars are spent on procedures shown “unequivocally” to offer no benefits.

So, why are cardiologists still doing them? Researchers did some focus groups and concluded: “Although cardiologists may believe they are benefiting their stable patients with CAD [coronary artery disease] by performing PCI, this belief appears to be based on emotional and psychological factors rather than on evidence of clinical benefits.”

“The sense of irrationality surrounding this practice is so strong that the phenomenon has been coined the oculostenotic reflex (I see a stenosis; I stent it).” They see a narrowing and stent it as though they can’t even help themselves.

Since the procedure carries some risks, including death, there’s an argument that stents should only be used for individuals who are actively having heart attacks and are in an emergency or unstable situation. Thankfully, there are now published, appropriate-use criteria in place to help guide cardiologists, and the good news is that 82 percent of stents are “reported to be performed in emergency or unstable situations.” So, we can disregard that ORBITA study that showed there was no benefit in stable patients since it’s now almost always performed only in unstable patients, right? Well, that’s how it’s almost always reported. “There are 2 ways a physician can become compliant. One is to do fewer unnecessary procedures”—which is the whole point (but where’s the money in that?)—“and the other is to make unnecessary procedures seem necessary.”

Is the implication that a doctor would try to game the system by telling a patient that they had a much more serious, unstable disease than they actually had, so the procedure could be carried out anyway? This is referred to as “upcoding.” Another word for it would be “fraud.” Researchers found that “some of that decline [in inappropriate use] may be driven by upcoding, falsely and intentionally misclassifying patients with stable angina as UA,” having unstable angina. As soon as those appropriate-use criteria went into effect, suspiciously, there was a four- to tenfold greater increase in rates of stents for acute coronary syndromes like heart attacks. “In New York, the proportion of PCIs labeled as acute, but performed as outpatient procedures, increased 14-fold…” There’s no biologically plausible reason why that would happen, so they were unnecessary procedures with unnecessary cost and unnecessary patient harm. And harm not only from the risk of getting an unnecessary stent but also from lying to the patient by exaggerating how bad their heart disease is. “This practice, at best, damages the credibility of the profession, increases health care spending, violates patient autonomy, puts the patient at risk of procedural complications and, at worse, may cross the threshold into criminal activity…”

What’s the solution? There could be an independent review panel to protect patients. “Simpler might be to remove the financial incentive to perform more procedures.”

“How many established standards of medical care are wrong? It is not known.” Bloodletting was the standard of care for thousands of years, for example. “Rigorous questioning of long-established practices is difficult. There are thousands of clinical trials, but most deal with trivialities or efforts to buttress the sales of specific products. Given this conundrum, it is possible that some entire medical subspecialties are based on little evidence.”

In the landmark COURAGE trial that showed stents were useless for extending life, what did seem to determine longevity? Ironically, in the case of heart stents, it was how many risk factors the patients were able to control. Those who achieved all six by lowering their blood pressure, cholesterol, weight, and smoking, while improving their diets and activity, had five times the survival over the subsequent 14 years than those who didn’t, as shown below and at 4:36 in my video Heart Stents and Upcoding: How Cardiologists Game the System.

Should we be surprised that angioplasty and stents fail to improve prognosis? After all, they do nothing to modify the underlying disease process itself. In other words, it doesn’t treat the cause. Even if stents helped with symptoms beyond the placebo effect, they would still just be treating the symptoms and not the disease. So, it’s no wonder the disease continues to progress until the patient is disabled to death. Dr. Esselstyn wrote, “Thus, the leading killer of men and women in Western civilization is being left untreated. What is being practiced is ‘palliative cardiology’: nontreatment of heart disease leading to disease extension and frequently an eventual fatal outcome.”

Deaths by the planeload every week, are “regarded as unfortunate,” rather than a national, preventable tragedy. “It is as though in ignoring this dairy, oil, and animal-based illness, we are wedded to providing futile attempts at temporary symptomatic relief”—rather than the cure.

Thankfully, “we are on the cusp of a seismic revolution in health…not another pill, procedure, or operation,” but instead treating the underlying cause of heart disease with whole food, plant-based nutrition, “the mightiest tool medicine has ever had in its toolbox.”

To get there, we need to fight a key nutrition deficiency in education. A study found that 90 percent of cardiologists reported receiving no or minimal nutrition education during their cardiology training, leaving fewer than one in ten feeling confident in their nutrition knowledge. So, maybe it’s a good thing that most spend just three minutes or less discussing nutrition with their patients. Only one in five cardiologists themselves even ate five servings of fruits and vegetables a day.

Thankfully, this lifesaving information is slowly but surely getting out there. “Medical education has focused on being the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff rather than a fence at the top. Money talks, and there’s very little money in promoting eating broccoli and going for a walk, despite them being much more effective.” I was so eager to see the citation they used for that and was so honored when I did, as shown below and at 7:14 in my video.

April 24, 2025

Why Use Stents When They Don’t Work?

Again and again, studies have shown that doctors tend to make clinical decisions for patients based on how much they themselves will get paid.

In 2007, we learned from the COURAGE trial that angioplasty and stents—percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—don’t reduce the risk of death or heart attack, but patients didn’t seem to get the memo. Only 1 percent realize there was no mortality or heart attack benefit, perhaps because most cardiologists fail to mention that fact. One can imagine that if patients actually understood that symptomatic relief was all they were going to get, with “no additional mortality benefits,” they’d be less likely to go under the knife. Then, ten years later, the ORBITA trial was published, showing even the promise of symptom relief was an illusion.

“The implications of ORBITA are profound and far-reaching. First and foremost, the results of ORBITA show unequivocally that there are no benefits for PCI compared with medical therapy for stable angina,” that is, heart disease. Basically, patients would be risking “harm for no benefit. It is hard to imagine a scenario where a fully informed patient would choose an additional invasive treatment for no added benefit.” Remember the stent consent form I discussed previously, shown below and at 1:17 in my video Why Are Stents Still Used If They Don’t Work?:

Now, it looks like this, seen below and at 1:21.

So, is the ORBITA trial the “last nail in the coffin for PCI in stable angina?” That is, for stents in non-emergency situations? An editorial in the journal Cardiovascular Revascularization Medicine disagreed, pointing to “the broad angina relief that occurred in both arms.” In other words, stents helped—even if the sham operation without stents helped just as much. So, “if the patient is treated with PCI and is benefiting from the ‘placebo effect,’ who am I to interfere with that benefit of this ‘therapy’?” In that case, why not perform fake surgeries? Stent placement can cost around $40,000. It’d be cheaper to just fake it all. The reason we shouldn’t keep electively stenting people is because there’s a body count. During stent placement, 2 percent of patients develop bleeding or blood vessel damage, while another 1 percent die or have a heart attack or a stroke. And because something is stuck in your chest, 3 percent of patients have a bleeding event from the blood thinners that must be taken. Or the blood thinners don’t work and the stent clots off and causes a heart attack.

Why are they still done when we not only don’t have evidence of benefit but, in many cases, we have explicit “evidence of no benefit”? One of the sources of resistance may be all the financial gain. These procedures make a lot of money for hospitals. Don’t expect them to begin promoting “lifestyle changes to combat heart disease. Nor will physicians quickly abandon a practice that both supports their income and seems to make sense.” Is it that simple? Is it that famous Upton Sinclair quote: “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it.” Think that’s just cynicism? Let’s ask doctors themselves.

Thousands of physicians were surveyed, and 70 percent “believed that physicians provide unnecessary procedures when they profit from them.” That’s what doctors themselves believe. And the data bear this out. Doctors have been shown to make clinical decisions for patients based on how much they get paid. For example, when choosing which chemotherapy to treat breast cancer, increasing a physician’s margin by 10 percent can yield up to a 177 percent increase in the likelihood of choosing one drug over another.

That may be why Caesarean sections “are more likely to be performed by for-profit hospitals as compared with non-profit hospitals.” “Operating on commission.” Pay surgeons per procedure, and you can increase surgery rates by 78 percent. Could that explain why we do 101 percent more angioplasties than any other affluent country? A study on “physicians’ financial incentives and treatment choices in heart attack management” found that they do indeed “respond positively to the payments they receive and that the response is quite large…Unconditionally, plans that pay physicians more for more invasive treatments are associated with a larger fraction of such treatments,” seeming to result in more invasive treatments. So, it may actually be quite common for patients to receive different treatments based on whether the doctor is getting paid per procedure.

One of my heroes, Dr. Caldwell Esselstyn—who always tries to see the best in people—had to admit that compensation may be playing a role. Evidence surfaced that “doctors have run up millions of dollars in medical bills by doing unnecessary stent implants,” doctors like Mark Midei who inserted 30 stents in a single day. That could be about a million dollars worth of billing. As a token of gratitude, a sales representative from the stent company spent more than $2,000 to buy “a whole slow-smoked pig, peach cobbler, and other fixings for a barbecue dinner at Dr. Midei’s home.”

“The US is just about the only developed country where health care is delivered on a fee-per-service basis and we very liberally incentivize physicians for doing invasive procedures,” explained the chief of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic. “The economic incentives are just too strong.”

April 22, 2025

Do Heart Stents Benefit Angina Chest Pain?

Sham surgery trials prove that procedures like non-emergency stents offer no benefit for angina pain—only risk to millions of patients.

Angioplasty and stents—percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—for stable, non-emergency coronary artery disease are among “the most common invasive procedures performed in the United States.” Though they appeared to offer immediate relief of angina chest pain in stable patients with coronary artery disease, that didn’t actually translate into a lower risk of heart attack or death. This is because the atherosclerotic plaques that narrow blood flow tend not to be the ones that burst and kill us. Symptom control is important, though, and is much of what we do in medicine, but cardiology has a bad track record when it comes to performing procedures that don’t actually end up helping at all.

Case in point: internal mammary artery ligation. Though it didn’t make much anatomical sense—why would tying off arteries to the chest wall and breast somehow improve coronary artery circulation?—it worked like a charm with immediate improvement in 95 percent of hundreds of patients. Could it have just been an elaborate placebo effect, and surgeons were cutting into people for nothing? There’s only one way to find out: Cut into people for nothing.

As I discuss in my video Do Heart Stent Procedures Work for Angina Chest Pain?, people were randomized to get the actual surgery or a sham (or fake) surgery where patients were cut open and the surgeon got to the last step but didn’t actually tie off those arteries. The result? “Patients who underwent a sham operation experienced the same relief.” Check out the testimonials: “Practically immediately, I felt better.” “I’m about 95 percent better.” “No chest trouble even with exercise.” “Believe I’m cured.” And these are all people who got the fake surgery. So, it was just an extravagant placebo effect. Think about it. “The frightened, poorly informed man with angina [chest pain], winding himself tighter and tighter, sensitizing himself to every twinge of chest discomfort, who then comes into the environment of a great medical center and a powerful positive personality and sees and hears the results to be anticipated from the suggested therapy is not the same total patient who leaves the institution with the trademark scar.” He hears how great he’s going to feel, goes through the whole operation, and leaves a new man with that trademark scar.

One sham patient was actually cured, though. “The patient is optimistic and says he feels much better.” The next day’s office note reads: “Patient dropped dead following moderate exertion.” This has happened over and over.

What if we burn holes into the heart muscle with lasers to create channels for blood flow? It seemed to work great until it was proven that it doesn’t work at all. Cutting the nerves to our kidneys was heralded as a cure for hard-to-treat high blood pressure until sham surgery proved that procedure was a sham, too. “The necessity for placebo-controlled trials has been rediscovered several times in cardiology, typically to considerable surprise.” Before they are debunked, “often a therapy is thought to be so beneficial that a placebo-controlled trial is deemed unnecessary and perhaps unethical.” That was the case with stents.

Hundreds of thousands of angioplasties and stents are done every year, yet placebo-controlled trials have never been done. Why? Because cardiologists were so unquestioningly sure it worked “that it might be unethical to expose patients to an invasive placebo procedure.” Why perform a fake surgery to prove something we already know is true? “When patients are aware they have had PCI, they have a clear reduction in angina and improved quality of life.” But what if they weren’t aware they had a stent placed inside them? Would it still work?

Enter the ORBITA trial. After all, “anti-anginal medication is only taken seriously if there is blinded evidence of symptom relief” against a placebo pill, so why not pit stents against a placebo procedure? “In both groups, doctors threaded a catheter through the groin or wrist of the patient and, with X-ray guidance, up to the blocked artery. Once the catheter reached the blockage, the doctor inserted a stent or, if the patient was getting the sham procedure, simply pulled the catheter out.”

The researchers had problems getting the study funded. They were told: “We know the answer to this question—of course, PCI works.” And that’s even what the researchers themselves thought. They were interventional cardiologists themselves. They just wanted to prove it. Boy, were they surprised. Even in patients with severe coronary artery narrowing, angioplasty and stents did not increase exercise time more than the fake procedure.

“Unbelievable,” read the New York Times headline, remarking that the results “stunned leading cardiologists by countering decades of clinical experience.” In response to the blowback, the researchers wrote that they “sympathize with our community’s shock and its instinct to invalidate the trial. Applying a positive spin could have smoothed the reception of the trial, but as authors we have a duty to preserve scientific integrity.”

While some “commended them for challenging the existing dogma around a procedure that has become routine, ingrained, and profitable,” others questioned their ethics. After all, four patients in the placebo group had complications from the insertion of the guide wire and required emergency measures to seal the tear made in the artery. There were also three major bleeding events in the placebo group, so they suffered risks without even a chance of benefit. But “far from demonstrating the risks of sham-controlled PCI trials, this demonstrates exactly what patients are being subjected to on a routine basis, without evidence of benefit.”

Those few complications in the trial “are dwarfed in magnitude” by the thousands who have been maimed or even killed by the procedure over the years. Do you want unethical? How about the fact that an invasive procedure has been performed on millions of people before it was ever actually put to the test? Maybe “we should consider the absence, not the presence, of sham control trials to be the greater injustice.”

When a former commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was asked at the American Heart Association meeting “whether sham controls should be required for device approval, he thought that it was more of a decision for the clinical community: ‘Do you want to get the truth or not?’”

April 17, 2025

The Risks vs. Benefits of Angioplasty and Heart Stents

What do physicians and stent companies have to say for themselves, given that they promote expensive, risky procedures with no benefit?

“Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)”—angioplasty and stent placement—“continues to be frequently performed for patients with stable [non-emergency] coronary artery disease, despite clear evidence that it provides minimal benefit…” The procedure does not prevent heart attacks or death for patients with stable angina pectoris, for example, yet nearly nine out of ten patients mistakenly believed that it would reduce their chances of having a heart attack. “At the same time, the cardiologists who referred them for PCI and those who performed the procedure generally did not believe that PCI reduces the risk for MI [myocardial infarction or heart attack] in stable angina.” Then why on earth were they doing it?

“Focus groups of cardiologists have documented a chasm between knowledge and behavior; while aware of the results of clinical trials”—that is, evidence to the contrary—“they recommend and perform PCI because they believe that it helps in some ill-defined way.” “Physicians tended to justify a non-evidence-based approach (‘I know the data shows there is no benefit, but’) by focusing on the ease of PCI and belief that an open artery was better”—even if it doesn’t actually affect outcomes—“while minimizing the risks of PCI.” The procedure only kills 1 in 150, so some are blaming the patients for not listening, but maybe the physicians are the ones who are ignoring the evidence.

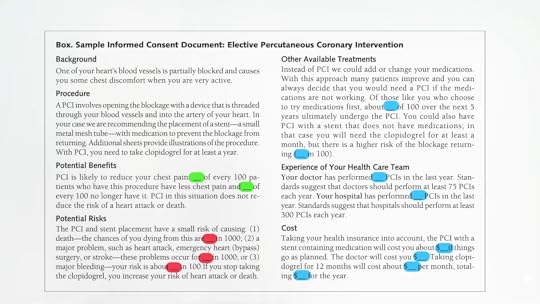

Or “physicians may have too poor a grasp of relevant statistics to adequately inform their patients.” Regardless, what we have is “a failure to communicate.” So, tools have been developed. For example, a sample informed consent document lays out the potential benefits and risks, even laying out how many procedures doctors have performed and any out-of-pocket costs. As you can see below and at 1:58 in my video Angioplasty Heart Stent Risks vs. Benefits, there are a lot of blanks to be filled in. What are some concrete numbers?

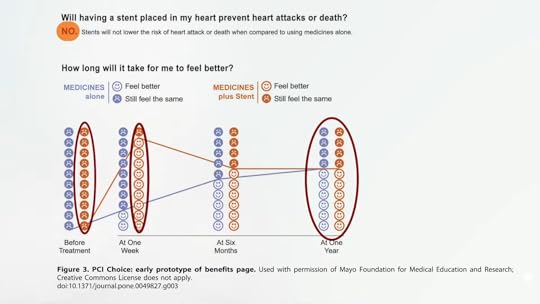

As you can see below and at 2:20 in my video, the Mayo Clinic came up with some prototype decision-making tools. In terms of benefits, “Will having a stent placed in my heart prevent heart attacks or death? No. Stents will not lower the risk of heart attack or death,” but a week later those getting stents report they feel better—though, a year later, even the symptomatic-relief benefit appears to disappear. Nevertheless, there appeared to be a benefit of temporary relief of chest pain. What about the risks?

As shown below and at 2:53 in my video, during the stent procedure, out of a hundred people, two will have bleeding or damage to a blood vessel and one will have a more serious complication, such as heart attack, stroke, or death. Then, during the first year after the stent placement, three will have a bleeding event because of the blood thinners that must be taken because of the foreign material in the heart, but that doesn’t always work, so two people will have their stent clog off, leading to a heart attack.

What does the world’s number one stent manufacturer have to say for itself? It acknowledges that the evidence shows that stents don’t make people live longer, but the manufacturer thinks living longer is overrated. If we only cared about living longer, in medicine, “entire disciplines would dwindle or even disappear, such as dermatology, ophthalmology, orthopedic surgery, and dentistry.” So why go to the dentist? Of course, the difference is that 80 percent of people don’t believe that getting a cavity filled is going to save their life, like they mistakenly do for stents, as shown here and at 3:18 in my video, and there isn’t a one in a hundred chance you won’t make it out of the dentist chair.

The stent companies actively misinform with ads making heart-warming copy. “Open your heart and your life.” “When you open up your heart, you open up your life. LIFE WIDE OPEN.” “Freedom begins here.” Their TV ads mention a few side effects, but it turns out they missed a few. More importantly, they’re giving the false impression that stents are more than just expensive, risky band-aids for temporary symptom relief. But what’s wrong with symptom relief? Even if the benefits are only symptomatic and won’t last long, what’s the problem if people think that outweighs the risk?

What if I told you that even the symptom relief might just be an elaborate placebo effect, and you could get the same relief from a fake surgery, so there really aren’t any benefits at all? We’ll see what the science says—next.

April 15, 2025

Heart Stents and Their Risks

Why are doctors killing or stroking out thousands of people a year for nothing? How do doctors even convince patients to sign up for procedures that are all risk without benefit?

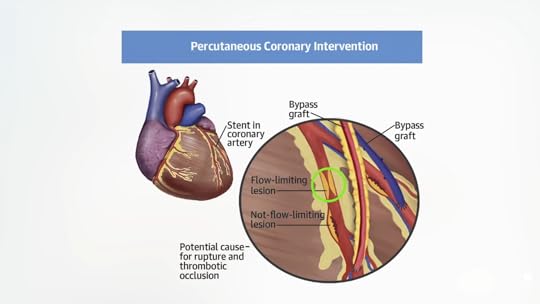

Millions of people have gotten stents for stable coronary artery disease (CAD), yet we now know that angioplasty and stent placement don’t actually prevent heart attacks, offer long-term angina pain relief, or improve survival for such patients. Why? Because the most dangerous plaques—the ones “most vulnerable to rupture or erosion—leading to a subsequent cardiac event,” that is, a heart attack, are not the ones doctors put stents into. They aren’t even the ones that are often seen on angiograms to be obstructing blood flow. So, “we need to avoid the ‘therapeutic illusion’ that we are accomplishing more than is shown by the evidence.” Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) looks great. Angioplasty and stents open up blood flow again, but if PCI doesn’t actually help, why do it?

We aren’t just talking about billions of dollars wasted either. Stent placement and the blood-thinner drugs that need to be taken can cause complications, including heart failure, stroke, and death, but the risks are relatively low. There is less than a 1 percent chance PCI will kill you or stroke you out, and the 15 percent risk of heart attack is only if your stent clogs off at a later date, which only happens in about 1 percent in the near term. There is a 13 percent chance of kidney injury, though, due to the dyes that have to be injected, but that typically heals on its own. The most serious complications, like death, happen in only about 1 in 150 cases, but that must be multiplied by the hundreds of thousands of procedures being done every year.

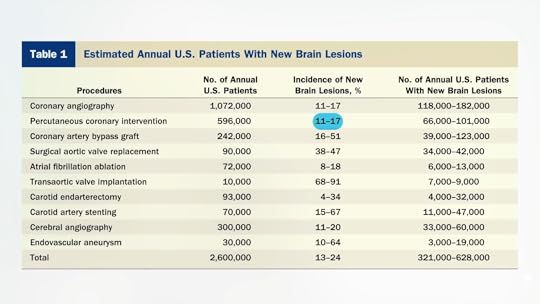

In an emergency setting, like while you’re actively having a heart attack, angioplasty can be lifesaving, but these hundreds of thousands of procedures are done for stable coronary artery disease, for which there appear to be no benefits. So, doctors are killing or stroking out thousands of people a year for nothing. And that’s not even counting the tens of thousands of silent mini-strokes that may contribute to cognitive decline caused by these procedures. Between 11 and 17 percent of people who go through angioplasty or stenting come away with new brain lesions, as you can see below and at 2:16 in my video The Risks of Heart Stents. That’s up to about one in six individuals.

How do doctors convince patients to sign up for PCI when it doesn’t lower the risks of death or heart attack, nor does it offer long-term symptom relief? Apparently, by conveniently failing to “inform the patient that PCI would not lower their risk of death or MI [myocardial infarction or heart attack], or that the symptom benefit is gone after 5 years,” thereby not offering long-term symptom relief.

Cardiologists are aware of how little they help, but studies have “consistently demonstrated” that patients think stents will reduce their risk of heart attack or death. More than 70 percent of patients erroneously believed that stents would extend their life expectancy or prevent future heart attacks. That’s why this study was done—to figure out “why patients overestimate these benefits.” Where are they getting these wild ideas? The answer is that many patients are being kept in the dark. Doctors, who overstate the benefits and understate the risks, may pressure patients into procedures that won’t benefit them the way they think. Why? Well, one reason may be because doctors may be paid per procedure. “Current reimbursement favors procedures over medication and lifestyle change, and it is possible that reimbursement may influence physicians’ recommendations.” Doctors are paid more for offering stents than recommending common sense diet and lifestyle changes.

Patients with stable coronary disease who undergo angioplasty and stent placement are frequently misinformed of the benefits. Of 59 recorded conversations between cardiologists and their patients, only two discussions included all seven elements of informed decision-making—telling people they have a choice, explaining the problem, discussing alternatives and the pros and cons, informing patients the procedure may not work, asking if they understand, asking if they have any questions, and asking them what they want to do. Only 3 percent of doctor-patient discussions about stents hit even just these basic elements! And this was the case when “the physicians and patients knew that they were being recorded, which could have affected their behavior. If so, it is likely that this represents a best-case scenario for these physicians.” Only 3 percent! Quoting from the Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine, when it comes to angioplasty and stents, “true informed consent rarely occurs.”

It’s no wonder that among the nearly 1,000 patients surveyed across ten U.S. academic and community hospitals, just 1 percent knew the truth. Remarkably, some blame the patients for their ignorance, saying patients are the ones who “commonly overestimate or misunderstand the benefits of treatment, such as patients with cancer who believe that palliative chemotherapy offers the potential for cure—the ‘therapeutic misconception.’”

“Why are so many patients having procedures with benefits that they poorly understand? Don’t look at the patients to find out why. Instead, examine the doctor’s motivation…Patients think they are having life-saving procedures because medical professionals want them to believe that this is so.” Now, it’s not like those 95 percent of cardiologists are lying to their patients and saying it will reduce their risk; they just happen to conveniently omit those details. But “[i]n the absence of information to the contrary, most patients and some doctors assume that PCI is life-saving and are biased towards choosing it. As a result, patients are rarely able to give true informed consent to undergo PCI.”

Why would they assume that? Because many have a wild concept of “‘personal care’—that a physician’s first obligation is solely to the patient’s well-being,” but isn’t that naïve? “In the absence of information, or even when presented with evidence to the contrary, patients tend to believe that treatments offered will be beneficial.”

It’s true, even if you explicitly tell patients that stents do not reduce the risk of heart attacks. You can cut that misperception in half “with relatively little effort—as little as 2 lines of text,” dispelling the myth in many people. But many participants continued to believe that angioplasty and stents prevent heart attacks, even when explicitly told they do not and given a detailed explanation of why they do not. After all, why would doctors be pushing them if they didn’t help? That’s a good question, which we’ll address next.

April 11, 2025

2024 Year in Review

Celebrating 2024. Celebrating Your Support.

What a year NutritionFacts.org had! Our successes, output, and outreach in 2024 are thanks to your support. We simply cannot do what we do without your generosity. Thank you.

You’re invited to read our 2024 Year in Review in full. Please share in the work we were able to accomplish. The lives we were able to touch.

Some of our highlights:

Dr. Greger’s book tour for his New York Times Best-Selling How Not to Age took him to more than 70 events, presenting to thousands of individuals in the United States, Canada, and Europe, and the companion four-part webinar series was our most popular ever, drawing more than 9,000 participants who wanted to learn how to live longer, more vibrantly.NutritionFacts.org hired Kristine Dennis, PhD MPH, as our first Senior Research Scientist.We released our first self-published book— Ozempic: Risks, Benefits, and Natural Alternatives to GLP-1 Weight-Loss Drugs .On the Chinese platform WeChat, we hit nearly 400,000 blog views in just one month.We prepared the manuscript for the forthcoming How Not to Age Cookbook , once again working with famed recipe creator Robin Robertson.See our 2024 Year in Review for the full scope of our work last year and a preview to what we’re focusing on in 2025.

Thank you, again, for your commitment to sharing evidence-based nutrition and health information and your dedication to NutritionFacts.org.

April 10, 2025

Why Aren’t Angioplasty Heart Stents More Effective?

Most heart attacks are caused by nonobstructive plaques that infiltrate the entire coronary artery tree. There is no such thing as “1-vessel disease,” “2-vessel disease,” or “left main disease.” Atherosclerotic plaque is continuous throughout the coronary arteries of heart attack victims.

In angioplasty, a tiny balloon is inserted into a narrowed coronary artery that feeds the heart to force it to open wider to improve blood flow. It wasn’t put to the test in a randomized controlled trial until 1992. It not only failed to prevent heart attacks, but it also failed to show any survival benefit. However, the researchers only followed patients for six months and included people with relatively minor diseases who might not have been sick enough to benefit from the procedure. Enter the MASS trial. Researchers enrolled those with severe blockage high up in their left anterior descending coronary artery—the widow-maker or widower-maker (since coronary artery disease is also the number one killer of women)—and followed them for years. The findings? There was no difference in subsequent mortality or heart attack rates. There were only about 200 patients in that trial, though. Maybe the benefit was so subtle that a greater number of patients were needed to tease out the effect. Enter the RITA-2 study, which randomized more than a thousand patients. Researchers did indeed find a clear difference in the risk of future death and heart attack, but it was in the wrong direction. The angioplasty group suffered twice the risk compared to those randomized to forgo surgery, as shown below and at 1:18 in my video Why Angioplasty Heart Stents Don’t Work Better.

This was all before stents came into vogue, though. Instead of just ballooning up the artery, how about permanently inserting a stent, a metal mesh tube, to prop open the artery, as you can see here and at 1:33 in my video? Surely, that’s got to help.

Enter the MASS-II trial, which, again, saw no benefit after one year—but no benefit was seen after five years or even ten years. Then came the Courage Trial, which randomized thousands of patients, and it, too, fell flat on its face.

Those mostly used bare metal stents, though, not the newer “drug-eluting” ones that release drugs slowly. And what about high-risk groups, such as those diagnosed with diabetes and other more serious diseases, or those who have 100 percent blocked arteries days after having a heart attack? In meta-analysis after meta-analysis, looking at five trials with 5,000 patients, there was no reduction in death, heart attack, or even angina pain. In ten trials with more than 6,000 patients, there was no benefit for survival, heart attacks, or pain relief. Now, we’re up to more than a dozen major trials and nothing: no benefit from angioplasty and stents. “Furthermore, multiple analyses have failed to identify a single high-risk subset that benefits…” How is that possible? You’re physically opening up blood flow.

The reason it doesn’t work is that the majority of heart attacks in real life are caused by narrowings less than 70 percent—“i.e., most likely non-flow-limiting lesions”—so the plaques in our arteries that kill us tend not to be the ones that are restricting blood flow. Shown below and at 3:21 in my video are two atherosclerotic plaques. The one circled in green and labeled “Flow-limiting lesion” is squeezing off the blood flow so much that it can be seen on an angiogram and doctors can go after it with a stent.

Problem solved and life saved, right? No, because it was the invisible one (circled in yellow below) that wasn’t even impeding blood flow that was going to kill us all along, as you can see here and at 3:27.

Indeed, most heart attacks are caused by nonobstructive plaques that don’t even cut blood flow by 50 percent, as seen below and at 3:40 in my video.

There’s a misconception, a “clogged pipe analogy of stable coronary heart disease [that] has been particularly difficult to dislodge,” in which cholesterol plaques slowly and inexorably encroach on blood flow, eventually cutting it off completely and triggering a heart attack. In reality, “coronary artery disease…is an inflammatory disease in which cholesterol from the blood is deposited in artery walls, causing an inflammatory reaction, like a pimple. When those pimples pop, they cause the blood in the arteries to clot at the site…Before rupture, these plaques often do not limit flow and may be invisible to angiography and stress tests. They are, therefore, not amenable to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI),” that is, to angioplasty and stents. Old plaques are like “scarred old pimples.”

The tightest blockages are made up of mostly calcified and dense fibrous scar tissue. They can still rupture and kill us, but there are so many more of the smaller lesions brewing, which are hidden from view. The way we visualize coronary arteries is with an angiogram. X-rays are taken after a black-looking dye is injected into the arteries, so we can only see plaques that encroach on the blood flow. That’s why we get these kinds of tip-of-the-iceberg illustrations, the point of which “is to emphasize that most of the atherosclerotic plaque in the coronary arteries is not seen well by angiography,” as you can see below and at 4:49 in my video. To really understand what’s going on in people’s arteries, we must turn to autopsy. William Clifford Roberts is probably the most pre-eminent cardiovascular pathologist in the world. What did he learn after studying coronary arteries for 50 years? After examining nearly 2,000 bodies, he learned that atherosclerosis is a systemic disease.

“In patients with fatal coronary artery disease…the quantity of plaque is enormous. There is not just 1 plaque here, another plaque there, with normal lumen [clean arteries] between plaques. Plaques are continuous! Not a single 5-mm segment is devoid of plaque” in the entire coronary artery tree. So, says Dr. Roberts: “Isolated coronary disease is a myth. There are no such things as ‘1-vessel disease,’ and ‘2-vessel disease.’ Plaque is in all of the epicardial coronary arteries if it is in 1 of them.”

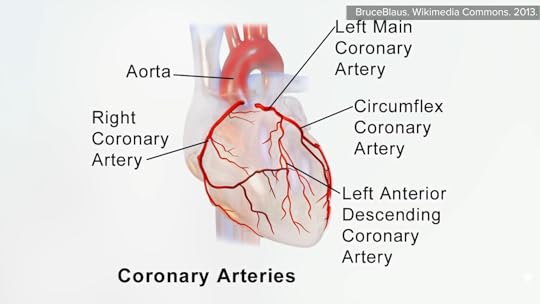

Four main coronary arteries feed the heart—the right coronary artery, the left main coronary artery, the circumflex coronary artery, and the left anterior descending coronary artery, as seen here and at 6:00 in my video.

If we add up their lengths, that’s about 11 inches (28 cm) of coronary arteries, which, for examination, can be cut into about 50 quarter-inch (5-mm) slices. Shown below and at 6:17 in my video is what is seen: Plaque isn’t gunking up one or two slivers but throughout all the coronary arteries. If we look at more than a thousand of these slices from dozens of patients who died of heart attacks, “not a single segment was devoid of plaque.” So, it’s no wonder that stenting open in just one area has no impact on heart attacks or death.

April 8, 2025

The Effectiveness of Angioplasty and Heart Stent Procedures

There are demonstrably no benefits to the hundreds of thousands of angioplasty and stent procedures performed outside of an emergency setting. They don’t prevent heart attacks, enable you to live longer, or even help with symptoms any more than placebo (sham) surgery.

Large national cardiology conferences may attract the majority of cardiologists across an entire country, convening them in one place. “While at the large cardiology conventions…[it’s been] joked that the convention center would be the safest place in the world to have a heart attack.” And, indeed, that’s when the American Heart Association president had his, within hours of his presidential address. With so many of the nation’s top cardiologists at a conference, that may be a bad time to go into cardiac arrest anywhere else, though. You don’t know until you put it to the test.

To much surprise, researchers found substantially lower mortality among those going into cardiac failure or cardiac arrest during the dates of national cardiology meetings. Why is the death rate lower when most of the cardiologists are away? “‘One explanation for these findings is that the intensity of care provided during meeting dates is lower and that…the harms of this care may unexpectedly outweigh the benefits,’ the researchers wrote.” Their results “echo paradoxical findings documented during a labor strike by Israeli physicians in 2000, in which hundreds of thousands of outpatient visits and elective surgical procedures were canceled, but by many accounts mortality rates dramatically fell during the year.” And it wasn’t just one strike. “Doctors’ strikes and mortality” have been looked at multiple times. In all reported cases, “mortality either stayed the same or decreased during, and in some cases, after the strike.” In four of the seven cases, “mortality dropped as a result of the strike, and three observed no significant change in mortality during the strike or in the period following the strike.”

The fact is that many current medical practices have been found to offer no benefit and present potential harm. Even physicians themselves estimate that about one-fifth of medical care is unnecessary. A national summit was convened by The Joint Commission, which accredits hospitals, and the American Medical Association to identify areas of overuse, “described as the provision of treatments that provide zero or negligible benefit to patients, potentially exposing them to the risk of harm.” Five practices were called out, including prescribing antibiotics for viral upper respiratory tract infections and spending a billion dollars prescribing drugs that don’t work (and, if anything, make things worse). Another overused practice identified was elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)—in other words, angioplasty and stents, as I discuss in my video Do Angioplasty Heart Stent Procedures Work?.

To get everyone on the same page before we dive in: Coronary artery disease, the number one killer of men and women, involves blockages in the blood vessels that supply the heart muscle itself. Low blood flow can lead to angina, a type of chest pain, or, if it’s severe enough, to a heart attack. Plant-based diets and lifestyle programs have been shown to reverse these blockages by treating the cause of why our arteries are clogging up in the first place, but for those unable or unwilling to change their diets, there are drugs that can help, as well as more invasive treatments, such as open-heart surgery to try to bypass the blockage or percutaneous coronary intervention, when “doctors insert small balloons or tunnels (stents) attached to flexible tubes (catheters) into the large blood vessels in the patient’s groin and thread them up into the heart. The stent and catheter are passed through the blocked vessels, a process that opens up the vessels.” In this way, they can get inside the blocked vessels and try to open them up and keep them propped open. During a heart attack, this can be lifesaving, but hundreds of thousands of these procedures are performed every year for stable angina, meaning on a non-emergency basis. It can relieve angina symptoms “but it does not reduce a person’s chances of having or dying of a heart attack.”

However, not everyone knows that. “Some patients and doctors mistakenly believe that PCI does more than just reduce symptoms.” That’s one of the reasons I’ve created a video series on the topic. As Harvard put it: “Stents are for pain, not protection.” Then, unbelievably, it was discovered that stents may not even help with pain, as revealed in a double-blind, randomized controlled trial. People can be blinded to the active treatment in a drug trial by receiving a placebo sugar pill, but wouldn’t they notice if they had surgery? If a doctor cut into their groin? Not if they had sham surgery—placebo surgery. “In both groups, doctors threaded a catheter through the groin or wrist of the patient…up to the blocked artery. Once the catheter reached the blockage, the doctor inserted a stent or, if the patient was getting the sham procedure, simply pulled the catheter out.” The results? Those who underwent the fake surgery did just as well as those who had the regular PCI surgery.

There are no benefits to angioplasty and stents outside of an emergency setting. They don’t prevent heart attacks, they don’t enable us to live longer, and they don’t even help with symptoms. “Since the procedure carries some risks, including death, stents should be used only for people who are having heart attacks…” How are hundreds of thousands of people getting these operations for nothing? How do the doctors justify it? Is it just greed? How do they get patients to consent to it? Do they just not tell them the truth? And why doesn’t it work? After all, a blocked artery is being opened up. There are just so many questions, which we’ll start addressing next.

April 3, 2025

What About Millet and Diabetes?

What were the remarkable results of a crossover study randomizing hundreds of people with diabetes to one and a third cups of millet every day?

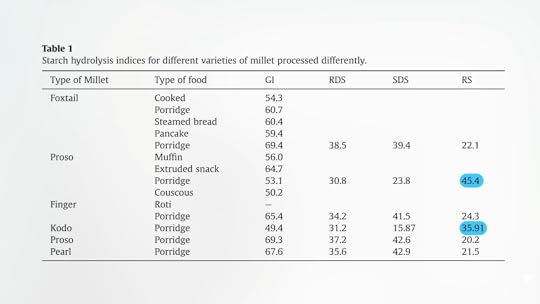

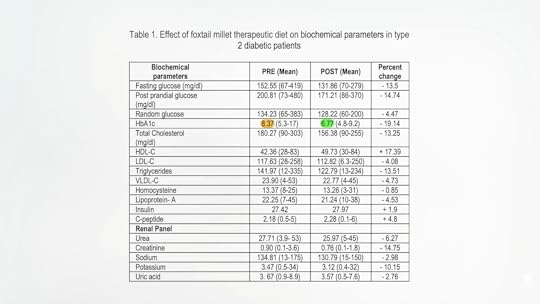

How does millet come to the help of people with diabetes? A substantial portion of the starch in millet is resistant starch, meaning it’s resistant to digestion in our small intestine so it provides a bounty for the good bugs in our colon. Below and at 0:28 in my video The Benefits of Millet for Diabetes is a table showing how the various millets do. As you can see, they’re all much higher in resistant starch than more common grains, like rice or wheat, but proso and kodo millets lead the pack.

What’s going on? The protein matrix in millet not only acts as a physical barrier but also partially sequesters our starch-munching enzyme, and the polyphenols in millet can also act as starch blockers themselves.

Millet has markedly slower stomach emptying times than other starchy foods, too. When we eat white rice, boiled potatoes, or pasta, our stomach takes about an hour to digest it, before it begins to slowly release it into our intestines, and it takes about two or three hours to empty about halfway. When we eat sorghum or millet, though, stomach emptying doesn’t even start for two or three hours and it may take five hours to empty just halfway, as you can see below and at 1:22 in my video.

Note that this was the case with both a thick millet porridge and a millet couscous. “The non-viscous millet couscous meal was also equally slow in [stomach] emptying. This suggests that there is an intrinsic property” of millet itself that helps slow down the rate of stomach emptying, which should blunt the blood sugar spike. What happened when it was put to the test?

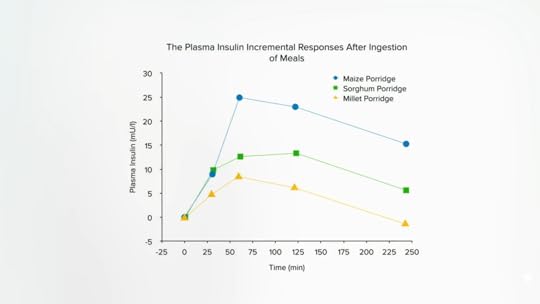

Indeed, millet caused about a 20 percent lower surge in blood sugar than the same amount of carbohydrates in the form of rice. Remember how excited I was to show you how it only took the body about half the insulin to handle sorghum compared to a grain like corn? Well, millet did even better, as seen here and at 2:07 in my video.

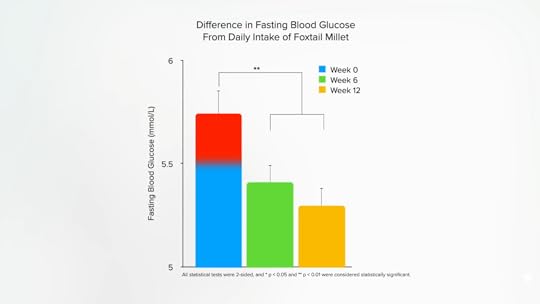

When a group of prediabetic individuals were given about three quarters of a cup of millet a day, within six weeks, their insulin resistance dropped so much that their prediabetic fasting blood sugars turned into non-prediabetic blood sugars, as shown below and at 2:22 in my video.

This “self-controlled clinical trial,” with the same subjects before and after, is just a sneaky way of saying it’s an uncontrolled trial. There was no control group in which participants either didn’t add the millet or added something else, and we know that just being under scrutiny in a study can cause people to eat better in other ways. So, we don’t know what role, if any, the millet itself played. What we need is a randomized, controlled, crossover trial where the same people eat diets with and without millet so we can see which works better. And here we go: a randomized, crossover study with hundreds of patients following an American Diabetes Association-type diet with and without about one and a third cups of millet every day. Researchers found that the millet-based diet lowered hemoglobin A1C levels, meaning there was an improvement in long-term blood sugar control, as well as the achievement of some side benefits like lowering cholesterol.

The target for good blood sugar control recommended by the American Diabetes Association is an A1C of less than 7. The participants started out at 8.37, but after a few months on millet, their A1C dropped to an average of 6.77, as seen here and at 3:35 in my video.

Is it just because they lost weight? No, which suggests it was an effect specific to the millet. The researchers didn’t just give them millet, though. They mixed the millet with split black lentils and spices, and we know from dozens of randomized, controlled experimental trials in people with and without diabetes that consuming pulses—beans, split peas, chickpeas, and lentils—can improve long-term measures of blood sugar control like A1C levels. So, while the researchers “concluded that millets do have a potential for a protective role in the management of diabetes,” a more accurate conclusion might be a mix of millets and lentils can be protective. The spices may have helped, too. The researchers didn’t say which spices were used, and I couldn’t get in contact with the authors, but a similar study done by one of the same researchers included about a daily tablespoon of a mixture of fenugreek, coriander, cumin, and black pepper, with a fifth spice, perhaps cinnamon or turmeric.

April 1, 2025

Is Millet a Nutritious Grain?

Millet isn’t the name of a specific grain, but a generic term that applies to a number of totally different plants. Which is the most healthful

“Millets are highly nutritious but vastly ignored as a main source of food primarily due to lack of awareness.” Have you heard of ancient grains? Millets aren’t messing around. Arguably, they are the first grains cultivated by humankind—dating back not only 5,000 years, but maybe 10,000.

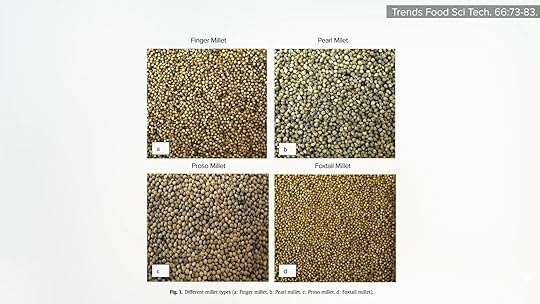

Why millets and not just millet? I had no idea that “millet” wasn’t the name of a specific grain. In fact, millet is a generic term that doesn’t just apply to different species but to a number of totally different plants. There are “major and minor millets,” pearl millet, which is what most people think of as millet, and also proso, foxtail, and finger millets, which are all completely different grains. Although they look similar, they aren’t the same, as you can see below and at 1:05 in my video Studies on Millet Nutrition: Is It a Healthy Grain?.

Fiber is one of the main things we look for in whole grain, and Kodo millet’s fiber content is off the charts. But, compared to other grains, finger and foxtail millets also beat out the bunch. Note, though, that pearl millet (the one most people think of as millet) is really on the low side. But looking at the polyphenol content, even plain millet beats out the other grains, including sorghum, which I previously hyped for how much polyphenol it contains. But, again, Kodo millet seems to win the day, as you can see below and at 1:39 in my video.

When it comes to total antioxidants, though, Kodo and finger millets are comparably high, as shown here and at 1:43.

When it comes to nutrition, finger millet is said to have eight times more calcium than other grains, but, to me, it looks like it has ten times the calcium. It’s just off the charts, as you can see here and at 1:55 in my video.

It also has three times as much calcium as milk. Some of the millets are exceptionally high in iron too. Regular millet is high, but barnyard millet has about five times more iron than steak.

So, it’s nutritious, but what about specific potential health benefits? In the medical literature, you can read statements like: Millets “may prevent cardiovascular disease by reducing plasma triglycerides in hyperlipidemic rats.” But who cares whether food reduces cardiovascular disease in rodents except for those with pet rats or mice?

An epidemiological study in China found lower esophageal cancer mortality rates in areas where residents ate more millet and sorghum, compared to corn and wheat. That may have been due more to avoiding a contaminating carcinogenic fungus than to the benefits of millet itself, though. Studies have shown that millets may be effective against cancer cell proliferation in a petri dish, with Kodo and proso millets rapidly inhibiting cancer cell growth, compared to pearl or foxtail millet, as shown below and at 3:02 in my video, knocking down the growth of cancer cells, but leaving normal cells alone. Also, millets were found to reduce the growth of colon cancer cells, human breast cancer cells, and human liver cancer cells, and also potentially help to prevent metastases by inhibiting cancer cell migration. My patients are neither pets nor petri dishes, though, and to date, there have been no clinical cancer trials with millet.

Are there any unique health-promoting attributes? Some know finger millet for its health benefits, such as lowering blood sugar and cholesterol and having anti-ulcer characteristics, but the anti-ulcer study researchers cite just notes that some of the areas with a low incidence of ulcers also happened to be regions where residents eat millet, as shown here and at 3:49 in my video, and that’s far from establishing cause-and-effect.

And the cholesterol-lowering study cited? It explores what happens when you take tail tendons from rats and soak them in sugar and millet! The blood-sugar-lowering benefits are legitimate, though. “Apart from the fact that millets do not contain gluten,” which is good for the 1 or 2 percent of people who have celiac disease or non-celiac gluten sensitivity, “millets can also be exploited in the management of type II diabetes due to their hypoglycemic [blood-sugar-lowering] property, as reported by several studies on millets and millet-based foods”—done with actual people, which we’ll cover next.

Isn’t it mind-blowing that millet isn’t actually a grain but a generic term? I learn something new every day—and make videos about it for you.

I have a few millet recipes in The How Not to Diet Cookbook, including Millet Risotto with Mushrooms, White Beans, and Spinach. Find it at your local library or wherever you get your books. (As always, all proceeds from my books are donated to charity.) You can also substitute millet for the barley and/or rye in my Basic BROL Bowl.

This is part of an extended series, which includes another three videos listed in the related posts below.