Michael Greger's Blog, page 6

March 27, 2025

Does Processed Meat Affect Our Lung Function?

If the nitrites in foods like ham and bacon cause lung damage, what about “uncured” meat with “no nitrites added”?

“Recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) classified processed meat as carcinogenic to humans.” Also known as cured meat, such as bacon, ham, hot dogs, lunch meat, and sausage, processed meat is definitively cancer-causing. What’s more, “high processed meat consumption has also been associated with increased risk of all-cause mortality”—that is, dying prematurely from all causes put together—“and is a risk factor for several major chronic diseases, such as type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease, and stroke.” What about lung issues like asthma?

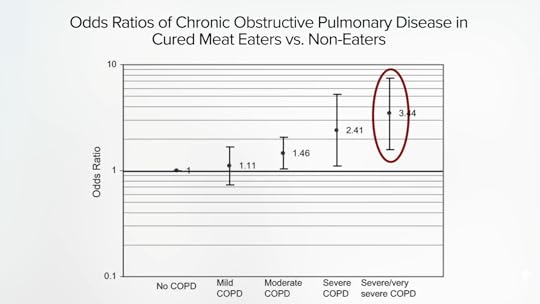

As I discuss in my video Does Processed Meat Affect Our Lung Function?, nitrites are added to processed meats as preservatives to preserve their pink hue (so the meat products don’t turn gray), keep them less rancid-tasting, and prevent the growth of diseases like botulism. But, if that same sodium nitrite is put into the drinking water of lab animals, they develop emphysema. Nearly all of them develop emphysema. That was the extent of the scientific knowledge we had on the subject going into 2007, then this study was published: “Cured Meat Consumption, Lung Function, and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease Among United States Adults.” It found that frequent consumption of cured meat is associated with an increased risk of people developing diseases like emphysema, a form of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). As you can see below and at 1:32 in my video, eating it every other day appeared to triple the odds of severe COPD.

Since it was a snapshot-in-time study, we don’t know which came first, the sausage or the COPD. For that, we need prospective studies that follow people over time, and the big twin Harvard studies in women and men both found that “the risk of newly diagnosed COPD increased with a greater consumption of cured meats after adjustment for many important confounders.”

We now have studies involving hundreds of thousands of people showing that higher consumption of processed meat is associated with a 40 percent increased risk of COPD. It comes out to about an 8 percent higher risk of COPD for each hot dog eaten in a week or each weekly breakfast link sausage. What is going on?

Yes, there are advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), so-called glycotoxins that “occur naturally in meat and are formed through heat processing,” that may be pro-inflammatory, as well as saturated fat that can also trigger inflammation in the airways. And there’s the high salt content that can present a potential risk for lung inflammation, and the suggestion that processed meat intake may increase systemic inflammation in general. However, the reason attention has focused on the nitrites is because nitrites themselves may be “one of the mechanisms by which tobacco smoke causes COPD” and other diseases like emphysema. “Cured meats are the principal source of dietary nitrites,” but “nitrites are also byproducts of tobacco smoke.” One of the main constituents in cigarettes, besides carbon monoxide and nicotine, are nitrogen oxides that are converted in the lungs to nitrites.

The way nitrites appear to cause lung damage is by affecting connective tissue proteins like collagen and elastin, which are what help keep the airspaces in our lungs open. But nitrite can modify these proteins in ways that “mimic age-related damage, including elastin fragmentation.”

With that much lung injury, it’s logical to assume that processed meat consumption could also exacerbate the disease of those who already have it. And, indeed, cured meat consumption increases the risk of people with COPD ending back in the hospital; those eating more cured meat on average have about twice the risk of readmission. It appears the more you eat, the worse it is, as seen here and at 3:56 in my video.

“Regarding lung health, processed meat intake has been associated with a likely increased risk of lung cancer, decline in lung function and chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD),” but what about asthma? High consumption of processed meat has also been “associated with higher asthma symptoms.”

We know that “higher maternal intake of meat before pregnancy may increase the risk of wheezing” in her children later on, based on a study of more than a thousand mother-child pairs. (And we aren’t talking about aspirating meat into our lungs and getting misdiagnosed with asthma.) In fact, “those who ate the most cured meats were 76% more likely to experience worsening asthma than those who ate the least.” Since obesity is a likely risk factor for asthma, might meat’s influence be indirect, by contributing to weight gain? That may be a small part of it, but the main effect appears to be direct, “suggesting a deleterious role of cured meat independent of BMI,” body mass index, a weight measurement. Put all the studies together, and “processed meat intake appears to be an important target for primary prevention of adult asthma.”

Even if you don’t have any lung issues, processed meat consumption was negatively associated with measures of normal lung function, while fruit and vegetable consumption and dietary total antioxidant capacity were associated with better lung function.

Can we just eat all-natural, uncured hot dogs, with “NO NITRATES OR NITRITES ADDED,” like these see here and at 5:35 in my video?

If you use a magnifying glass and peer at the small print, it says “except those naturally occurring in sea salt and cultured celery juice.”

See, to avoid saying “added nitrites,” food manufacturers may add something that has a lot of nitrates, like celery, and also bacteria, “a starter culture to convert the nitrate to nitrite.” So, nitrites are being added and consumers are being duped.

The European Union doesn’t allow this kind of consumer fraud and “considers the use of plant extracts containing high levels of nitrate with an intended technological purpose of preservation to be a deliberate use of a food additive,” and manufacturers must explicitly label their products as “containing nitrate or nitrite.” You can’t even call it natural. “In the European Union, ‘natural’ claims are also not permitted….”

When Consumer Reports put it to the test, it found the nitrite levels in all the products were essentially the same, so “‘no nitrites’ doesn’t mean no nitrites.” Consumer Reports and the Center for Science in the Public Interest have petitioned the U.S. Food Safety and Inspection Service of the Department of Agriculture to stop this misleading practice. Nitrites are nitrites, and “their chemical composition is absolutely the same, and so are the health effects.”

Yes, processed meat is a known carcinogen, but How Much Cancer Does Lunch Meat Cause?

I have many videos on both nitrites and nitrates. I know it can be confusing, so be sure to check them out.

March 25, 2025

Is There a Limit to How Many Lychee Fruit We Should Eat?

There is a toxin in lychee fruit that can be harmful, but is it harmful only under certain circumstances?

Lychee fruits have been widely used in many cultures for the folk medicine treatment of everything from farting to testicular swelling. (Arsenic, mercury, and lead are also included in many “traditional” remedies.) Lychees have also apparently “been shown to exhibit numerous health benefits,” but the studies cited include ones like this: “Protective Effect of a Litchi [Lychee]…-Flower-Water-Extract on Cardiovascular Health in a High-Fat/Cholesterol-Dietary Hamsters.” What are we supposed to get from that? We don’t eat lychee flowers…and we aren’t hamsters. Hard to argue with this, though: “Flavor is sweet, fragrant, and delicious,” which is why I love them so much. I then saw this: “A child-killing toxin emerges from shadows. Scientists link mystery deaths…to the consumption of lychees.”

In Vietnam, it’s called “nightmare” encephalitis. There were unexplained outbreaks in children coinciding with lychee harvesting. Children go to bed feeling fine, but they wake up the next morning “seriously ill with brain function derangement and seizures”—if they wake up at all. The same in India, killing up to nearly two out of three kids affected in some places. We’re talking about thousands of kids, so it became “one of the most pressing public health emergencies in India.” It was one of the “three long-standing mystery diseases listed in Wikipedia” and remained a mystery for more than two decades.

All clinical samples were negative for known brain viruses. So, some investigators thought it was caused by an unknown virus, while others thought it might have been due to the pesticides used in the orchards. All we knew was that it seemed to coincide with the lychee harvest. So, might the fruits have attracted fruit bats, then mosquitos could have fed on the infected bats and transferred some new virus from bats to people? Maybe, but why would toddlers and babies be mostly spared? Mosquitoes bite infants, too.

So, were kids swapping spit with the fruit bats by eating half-eaten fruits? “The investigators noted colonies of fruit-eating bats and the tendency of children eating fruits to fall to the ground and suggested the possibility of a bat virus (through saliva contamination on fruits) as a cause of the disease.” Or maybe it was because it was summertime, and they were all just getting heat stroke? Maybe, but why weren’t the pesticides or the heat affecting adults, too?

One of the clues that finally helped investigators tease out the mystery was that the children consistently had low blood sugars—in some cases, fatally low blood sugars. That kind of sounds like “Jamaican vomiting sickness.” Two children “were perfectly well” when they went to bed, but, by “the next morning, they started to vomit and were weak,” then unconscious, then both dead within 48 hours. That was all due to eating unripe ackee fruit, which contains a toxin known as hypoglycin, which prevents our liver from churning out blood sugar all night long to keep our brains alive while we sleep. Ackee is a member of the soapberry family, just like the lychee is. Aha!

As I discuss in my video Lychee Fruit and Hypoglycin: How Many Are Too Many?, Muzaffarpur is a leading lychee producer, and experts at the National Center for Litchi claim they “completely refuted” the lychee link. Nevertheless, independent researchers found it: Lychee fruit contains methylene cyclopropyl-glycine, nearly the same hypoglycin toxin “present in ackee fruits, popular in Jamaica.”

So, in the setting of malnourished children who already have depleted energy stores in their livers “(due to missed meals and poverty-related starvation),” low blood sugar sets in, and, due to the excessive consumption of lychee fruits, the production of new energy is blocked, and the trouble starts. “It is a social tragedy that children have to die in the 21st century due to…hypoglycemia [low blood sugar], which is an easily treatable condition and involves minimal costs.” It’s just as tragic that hungry children are forced to binge on lychees falling on the ground to get a meal. It’s like something out of Grapes of Wrath.

The happy ending, though, is that rather than just focusing on better treatments, local public health workers instead sought to treat the cause by educating people “that no child should go to bed at night without eating a cooked meal and for parents to restrict children eating litchis in the evening to none or very few.” Thankfully, “by applying these recommendations, the disease incidence had been dramatically reduced and death almost completely prevented.” In hindsight, it appears China had already started warning citizens about the dangers of lychees a decade earlier, but word had apparently not gotten around.

What are the implications in the West? In the United States, the Food and Drug Administration tried to protect people against poisoning with this toxin (which is not destroyed by heating) by mandating that canned ackee fruits coming into the country test below a certain level, but there are no such regulations when it comes to importing lychees. “Fortunately, the high cost of these imported fruits and the likelihood that [they] would be eaten in small quantities by well-nourished consumers, suggests there is little reason for concern in the USA.” That’s quite an assumption. Small quantities? You don’t know how I eat lychees. I used to sneak big bags of them—pounds of them—into movie theaters to snack on during the film. How many are too many to eat?

In a series of a few hundred poisoning cases, people reported eating 300 grams to a kilogram of lychee fruits. Each lychee is about 10 grams, so that’s 30 to 100 fruits. Most of the cases were children, though, so we can probably safely say 30 to 100 lychees are too many at one time for kids. What about adults? In a self-experiment, a researcher ate some lychees and measured the hypoglycin levels in his blood and urine, which stayed below the levels seen in the affected children. He ate 5 grams of canned lychee for each kilogram of his body weight, equivalent to about 45 lychee for the average American male, and didn’t suffer any ill symptoms.

What a fascinating story! A lot of research went into just this one topic, but it was all news to me, so I wanted to share it with you.

In general, Is Canned Fruit as Healthy? And, given the sugar content, How Much Fruit Is Too Much? Check out the videos to find out.

March 20, 2025

Heme Iron and Cancer

Laboratory models suggest that extreme doses of heme iron may be detrimental, but what about the effects of nutritional doses in humans?

In muscle meat, there is a heme protein that contributes to, well, the meaty taste of meat. There’s also a heme protein in the roots of soybean plants that can be churned out to provide a similar flavor and aroma in plant-based meat, which is used to make the Impossible Burger possible. The question is: Are there any downsides?

When the European Food Safety Authority was considering the safety of adding heme iron to foods, its main concern was a potential increased risk of colon cancer. As you can see below and at 1:00 in my video Does Heme Iron Cause Cancer?, we know meat causes cancer. Processed meat—bacon, ham, hot dogs, sausages, and lunch meat—is considered a Group 1 carcinogen, meaning we know it causes cancer in people with the same level of certainty that something like smoking causes cancer, whereas something like a burger probably causes cancer in people, kind of like DDT. But what’s the role of heme iron?

There are all sorts of potential mechanisms to explain the cancer risk. Meat has the pro-inflammatory long-chain omega-6 arachidonic acid and more of the aging- and cancer-associated methionine, trans fat, and endogenous hormones like IGF-1, not to mention the ones that are implanted in animals as “exogenous hormonal growth-promoters.” Then there are all the toxic pollutants that build up the food chain, like pesticides and formaldehyde.

According to the prestigious IARC, the International Agency for Research on Cancer, “there is strong evidence that HAAs [heterocyclic aromatic amines], by causing DNA damage, contribute to carcinogenic mechanisms associated with the consumption of red meat.” These DNA-damaging compounds are formed when muscle tissue is exposed to high, dry heat like grilling, roasting, baking, and broiling—basically anything above steaming or stewing. There is also “strong evidence” that the formation of so-called N-nitroso compounds contributes to the cancer-causing mechanism. Those are carcinogens that can form inside our gut when we eat meat. However, there is also “strong evidence that haem [heme] iron contributes to the carcinogenic mechanisms associated with red and processed meat.”

Normally I might leave it there, but other authoritative bodies I respect, like the American Institute for Cancer Research and the World Cancer Research Fund, are more tentative. While they agree there is some evidence that the “consumption of foods containing haem iron might increase the risk of colorectal cancer,” they consider the evidence suggesting such a connection to be limited.

Much of the available evidence is based on data from lab animals, such as the study titled “Dietary Heme Induces Gut Dysbiosis, Aggravates Colitis, and Potentiates the Development of Adenomas in Mice,” in which dietary heme was found to disrupt the gut flora, aggravate inflammation, and potentiate the development of intestinal tumors in mice. But it’s critical to note that, in all the laboratory animal models that have been used, the rodents ingested meat or heme equivalent to humans eating up to 40,000 pounds (18,000 kilograms) of meat a day. Even the smallest dose would be about a dozen daily Impossible Burgers.

In another study, ascribing “a central role for heme iron” in the development of colon cancer associated with meat intake, the authors claimed they “aimed at determining, at nutritional doses, which is the main factor involved and proposing a mechanism of cancer promotion by red meat.” So, heme “doses were chosen to mimic red meat consumption,” and, indeed, there was a significant increase in tumor load, as you can see here and at 3:41 in my video.

The researchers concluded that their “results strongly suggest that at concentrations that are in line with human red meat consumption, heme iron is associated with the promotion of colon carcinogenesis,” that is, cancer development. However, if you look at the actual diet given to the participants and do the math, it was 500 times the level of heme found in people’s diets, in excess of about 20 pounds of meat a day. Of course, even if they really did use the right doses, they’re still going to end up with data on the wrong species, which brings us to clinical studies that we’ll explore next.

This is part of a nine-video series on plant-based meats. If you missed any of the other earlier installments, check out the related posts below.

The final two videos in the series are coming up next. See Heme-Induced N-Nitroso Compounds and Fat Oxidation and Is Heme the Reason Meat Is Carcinogenic?.

March 18, 2025

Heme and Impossible Burgers

Is heme just an innocent bystander in the link between meat intake and breast cancer, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, and high blood pressure?

In an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the chair of nutrition at Harvard pointed out that many plant-based meats, such as burgers made by Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods, can be high in sodium. An issue specific to the Impossible burger is the “heme (an iron-containing molecule) from soy plants added to the burger patty to enhance the product’s meaty flavor and appearance.” Safety analyses have failed to find any toxicity risk specific to the soy heme churned out by yeast, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has agreed that it is safe, both for use as a flavor and color enhancer. In other words, it’s just as safe as the heme found in blood and muscle in meat—but how much is that really saying?

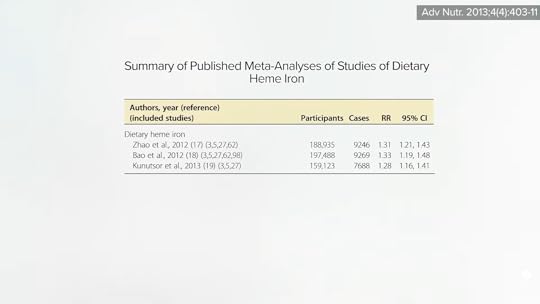

The concern raised in the JAMA editorial, for example, was that “higher intake of heme iron has been associated with…elevated risk of developing type 2 diabetes,” killer number seven in the United States. That isn’t all, though. “Higher dietary intake of heme iron is associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular disease,” as well, as killers numbered 1, 4, and 13—heart disease, stroke, and high blood pressure. But since heme is found mostly in meat, heme intake may just be a marker for meat intake. It’s like with diabetes: Four meta-analyses have been published to date, and they all reported the same link, as seen below and at 1:25 in my video What About the Heme in Impossible Burgers?. But there are a lot of reasons meat may increase diabetes risk, like its advanced glycation end-products (AGEs), which are produced when animal products are baked, broiled, grilled, fried, or barbecued. So, how do we know that heme isn’t just an innocent bystander?

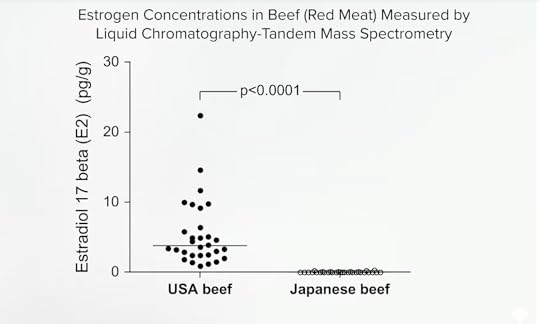

The same issue arises with the link between heme intake and increased breast cancer risk. Since heme iron comes from animal foods, it could be any of the other components in meat, like animal fat or meat mutagens, which are compounds in meat that can cause DNA mutations. And what about all the hormonal steroids implanted into cattle that may play a role in the development of breast cancer? A study in Japan found that beef imported from the United States contained up to 600 times the levels of estrogens like estradiol. You can see the comparison of U.S. beef to Japanese beef below and at 2:20 in my video. “Higher consumption of estrogen-rich beef due to hormone application might facilitate estrogen accumulation in the [human] body and thus affect women’s risk for breast cancer.” So, yes, heme iron intake was associated with breast cancer risk, but maybe that’s just because the heme and the hormones traveled together in the same package—meat.

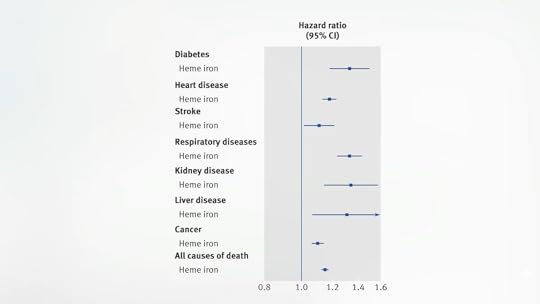

The NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study is about as good as any observational study can get. It is the largest prospective study on diet and health ever, following more than half a million men and women for more than a decade now. With such a huge dataset, its researchers could take advantage of the fact that different meats have different amounts of heme, so they could try to tease out the heme components, in effect, by comparing people eating different amounts of heme, but the same amount of meat, to see if heme is independently associated with the disease. And, indeed, that’s what they showed: “independent associations between the intake of heme iron and nitrate/nitrite in processed meat and mortality from almost all causes”—death from diabetes, heart disease, stroke, respiratory disease, kidney disease, liver disease, cancer, and all causes put together, as seen here and a 3:33 in my video.

The researchers calculated that about one fifth of the association between eating burgers and the shortening of our lifespan, for example, could be statistically accounted for by just the heme itself, but that’s assuming cause-and-effect. An “independent association” is still an association. You can’t prove cause and effect until you put it to the test in interventional studies.

Normally, we don’t necessarily care about the mechanism. When the World Health Organization designated bacon, ham, hot dogs, lunch meat, and sausages to be Group 1 carcinogens, meaning we know these products cause cancer in human beings, who cares if it’s the heme iron, the heterocyclic aromatic amines, the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, or the N-nitrosamines? They’re all wrapped up in the same place—processed meat—which we know causes cancer, so shouldn’t we try to stay away from it, regardless of the mechanism? With the advent of the Impossible Burger, we really do have to know, because, for the first time, we have a lot of heme without any actual meat, so we need to know if the heme itself is harmful. For that, we’ll have to turn to interventional studies, which we’ll cover next.

This is the sixth in a nine-part series on plant-based meats. If you missed any of the previous installments, see the related posts below.

Up next:

Does Heme Iron Cause Cancer? Heme-Induced N-Nitroso Compounds and Fat Oxidation Is Heme the Reason Meat Is Carcinogenic?March 14, 2025

Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching

The influenza virus has existed for millions of years as an innocuous intestinal virus of wild ducks. What turned a harmless waterborne duck virus into a killer? In his classic book Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching, Michael Greger, M.D. FACLM, founder of NutritionFacts.org and New York Times Best-Selling author, traces the human role in the evolution of this virus, whose humble beginnings belie its transformation into a potentially deadly strain with the potential to become the next pandemic.

Visit h5n1book.org to read the full text of Dr. Greger’s Bird Flu for free. Given the latest bird flu cases and outbreaks in 2025, the urgency in understanding animal-to-human diseases, their history and causes, and how we may prevent their emergence is once again paramount.

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, 14 years after his now-classic Bird Flu: A Virus of Our Own Hatching was published, Dr. Greger dove once again into the research and released How to Survive a Pandemic, an updated and expanded book on infectious zoonotic diseases. Borrow it from your local public library or purchase a copy.

March 13, 2025

Are Mycoprotein (Quorn) Products Good for Us?

Clinical trials on Quorn show that it can improve satiety and help control cholesterol, blood sugar, and insulin levels.

You may have heard about meats made from wheat protein (like Field Roast sausages and Upton’s bacon seitan), meats made from soybean protein (like the Impossible Whopper and Gardein’s wings), and meats made from pea protein (like Beyond Sausage and Good Catch’s fish-free tuna), but what about meats made from mycoprotein? A relatively new addition, meats made from the mushroom kingdom are popular in Europe and have been introduced into the U.S. marketplace, commercialized as Quorn, which makes cow-free beef, chicken-free chicken, fish-free fish, and pig-free pork, as seen here and at 0:35 in my video The Health Effects of Mycoprotein (Quorn) Products vs. BCAAs in Meat.

In terms of environmental impact, Quorn beef has a carbon footprint that’s at least ten times smaller than conventional beef, and Quorn chicken is at least four times lower than conventional chicken. Health-wise, “mycoprotein is high in protein and fiber, and low in fat, cholesterol, sodium, and sugar,” as one would expect. Most importantly, there have been clinical trials showing it may help control cholesterol, blood sugar, and insulin levels, as well as improve satiety. No surprise given that the fiber and the mycoprotein itself are fermentable by our good gut bugs, so it can also act as a prebiotic for our friendly flora.

There have been rare, authenticated reports of people with mycoprotein allergies and even more with unvalidated complaints, but, given how many billions of packages have been sold, the rate of allergic reactions may be on the order of around 1 in 9 million.

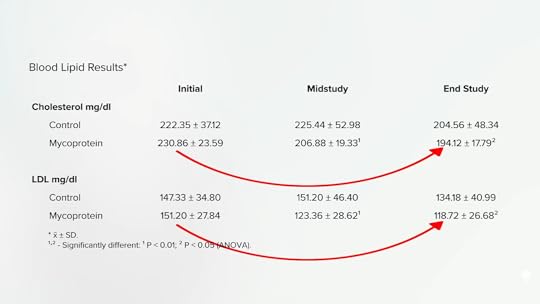

The cholesterol data, as seen below and at 1:40 in my video, have been converted into U.S. numbers. There were significant drops in total and LDL cholesterol—more than 30 points within eight weeks.

In terms of satiety, as I noted in my Evidence-Based Weight Loss presentation, both tofu and Quorn have been found to have stronger satiating qualities than chicken. Consumption of Quorn, for instance, cut down on subsequent meal intake hours later for lean subjects, as well as reduced it for overweight and obese individuals.

You know, it’s funny when the meat industry funds obesity studies on chicken. For its head-to-head comparison foods, it chooses items like “shortbread cookies and sugar-coated chocolates.” This is a classic drug industry trick where you make your product look better by comparing it against something worse. (Apparently, regular chocolate wasn’t bad enough to make chicken look better, so had to be chocolate coated in sugar.) But what happens when a chicken is pitted against a real control, like a chicken without the actual chicken? Chicken chickens out, as it was “clearly demonstrated that a Quorn-based meal has greater satiating efficiency than a chicken-based meal.” For example, when study participants ate a chicken and rice lunch, they ate 18 percent more of a dinner buffet four and a half hours later than those who had instead eaten a lunch of Quorn and rice and cut about 200 calories on average.

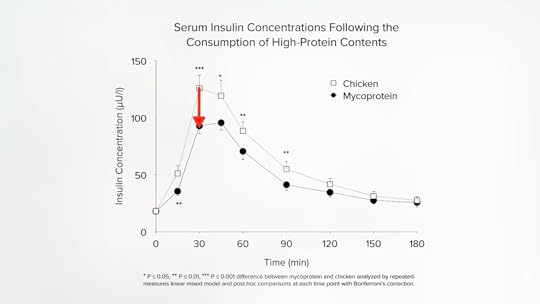

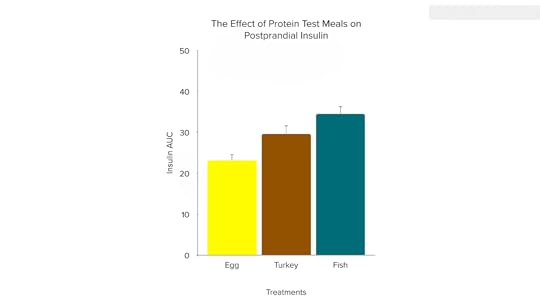

As seen here and a 3:01 in my video, part of the reason plant-based meats may be less fattening is that they cause less of an insulin spike. A meat-free chicken like Quorn causes up to 41 percent less of an immediate insulin reaction.

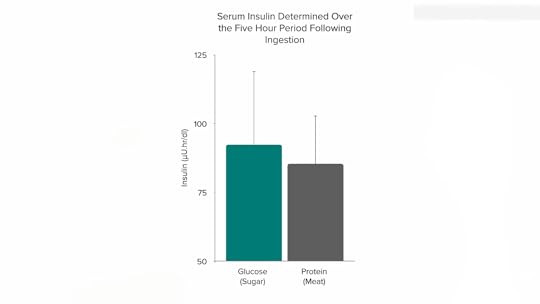

It turns out that animal protein causes almost exactly as much insulin release as pure sugar, as you can see below and at 3:03 in my video.

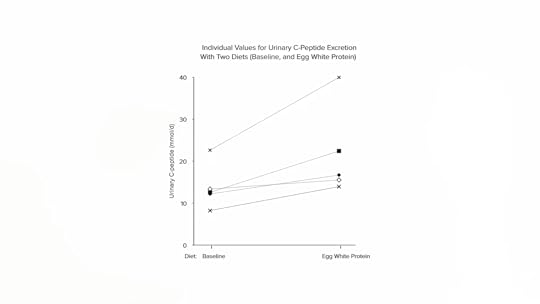

Just adding some egg whites to your diet can increase insulin output by 60 percent within four days, as seen here and at 3:16.

And fish may be even worse, as shown below, and at 3:21.

Why would adding tuna to mashed potatoes spike up insulin levels, but adding broccoli instead drop the insulin response by about 40 percent? It’s not the fiber, since giving the same amount of broccoli fiber alone provided no significant benefit. So, why does animal protein make things worse, but plant protein makes things better?

Plant proteins tend to have lower levels of the branched-chain amino acids, which are associated with insulin resistance—the cause of type 2 diabetes. You can show this experimentally. Give some vegans branched-chain amino acids, and you can make them as insulin-resistant as omnivores. Or, take omnivores and put them through a 48-hour vegan diet challenge, and within two days, you can see the opposite—significant improvements in metabolic signatures. Why? As the study is titled, “Decreased Consumption of Branched-Chain Amino Acids Improves Metabolic Health.” Those randomized to restrict their protein intake were averaging intake of literally hundreds more calories per day, so they should have gotten heavier, right? But, no. They actually lost more body fat. Restricting their protein enabled them to eat more calories, while at the same time, they lost more weight. More calories, yet a loss of body fat. And this magic “protein restriction”? The study participants were just eating the recommended amount of protein. So, maybe the researchers should have called the “protein-restricted” group the “normal protein” group or the “recommended protein” group, and the control group eating more typical American protein levels—and suffering because of it—the “excess protein” group.

Given the “restoration of metabolic health by decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids,” leaders in the field have suggested the invention of drugs to block their absorption to “promote metabolic health and treat diabetes and obesity without reducing caloric intake.” Or we can just try not to eat so many branched-chain amino acids in the first place.

They are found mostly in meat, including chicken and fish, dairy products, and eggs, which may help explain why animal protein has been associated with higher diabetes risk, whereas plant protein appears protective. So, “defining appropriate upper limits” of animal protein intake “may offer a great chance for the prevention of T2D [type 2 diabetes] and obesity.”

This is part of a nine-part series on plant-based meats. If you’ve missed any of the previous installments, check out the related posts below.

Up next:

What About the Heme in Impossible Burgers? Does Heme Iron Cause Cancer? Heme-Induced N-Nitroso Compounds and Fat Oxidation Is Heme the Reason Meat Is Carcinogenic?I mentioned my Evidence-Based Weight Loss presentation, which you can watch here.

March 11, 2025

Potatoes: What About Diabetes, Blood Pressure, Blood Sugar, and More?

There are so many ways we eat potatoes—baked, mashed, hashed, fried, scalloped, roasted, and more—but should we be eating them at all?

Potatoes and DiabetesIn 2006, the Harvard Nurses’ Health Study, which had followed the diets and diseases of tens of thousands of women for 20 years, found that greater potato intake was associated with a greater likelihood of getting type 2 diabetes, but of the hundred or so pounds of white potatoes Americans eat every year, most are deep fried and consumed as potato chips or french fries, and deep-fried foods are known to contain advanced glycation end products (AGEs), which we know are unhealthful. Researchers have found that just three servings of french fries a week is associated with a nearly 20 percent greater risk of type 2 diabetes, whereas there was only a tiny associated risk with potatoes in general, including fries.

There was still a diabetes link with mashed or baked potatoes, but people who eat more potatoes may eat more meat, and we know that animal protein is itself associated with increased diabetes risk. However, when researchers statistically adjusted for that, they still found an increased risk with potatoes.

Looking deeper, butter and sour cream are often put on mashed and baked potatoes, but when researchers tried to adjust for those and other such dietary factors, as well as effectively looking at the ratio between plant and animal fats and whether potato-eaters drank more soda or skimped on other vegetables, there still there seemed to be a potato-diabetes association.

By 2015, Harvard researchers had also looked into other cohorts, including the all-male Health Professionals Follow-Up Study to complement the all-female Nurses’ studies, and continued to find a small increased diabetes risk associated with baked, boiled, or mashed potatoes––though french fries appear nearly five times worse. The authors concluded that potatoes are considered to be a healthful vegetable in the Dietary Guidelines, though current findings cast serious doubts on that classification. (Walter Willett, the then-chair of Harvard’s nutrition department, went a step further, suggesting potatoes should be siloed with candy.)

Then, in 2018, a meta-analysis published on potato consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes combined all six of the prospective studies that had been done to date and found about a 20 percent increase in diabetes risk associated with each serving of potatoes a day. The researchers concluded that long-term, high consumption of potato may be strongly associated with increased risk of diabetes.

Does the story end there? If only there were a country where potato consumption was associated with a healthy diet. If potato consumption was still associated with diabetes there, then that would be concerning. As I discuss in my video Do Potatoes Increase the Risk of Diabetes?, a study out of Iran found that those eating the most boiled potatoes had only half the odds of developing diabetes. In Iran, not only is most of the potato consumption in the form of boiled potatoes, but those who eat potatoes have the healthiest diets and eat the most whole plant foods, such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and beans.

The bottom line is we don’t have convincing evidence to date that the intake of potatoes in general is linked to type 2 diabetes, but we should still probably hold the fries.

Potatoes and High Blood PressureWhat about potatoes and hypertension? And death? I dive into those topics in my video Do Potatoes Increase the Risk of High Blood Pressure and Death?.

Harvard researchers found that individuals who, on most days, ate potatoes—baked, boiled, or mashed, and not just french fries and potato chips—appeared to be at higher risk of developing high blood pressure. As mentioned above, salt and butter are often added to potatoes, but when they attempted to tease out the effects of salt and saturated fat, there still seemed to be a link between potato consumption and high blood pressure.

Again, though, what about the “meat” in “meat and potatoes”? The same Harvard researchers found that meat, including poultry alone, appeared associated with an increased risk of hypertension, as did a moderate amount of canned tuna. So, in the potato study, they endeavored to factor out any effects from the consumption of all types of meat yet still found an increased risk of hypertension associated with potato intake.

Two similar studies performed in Mediterranean Europe did not find any association between potato consumption and high blood pressure, though. Perhaps this is because, in that area of the world, potatoes aren’t typically smothered in butter and sour cream, and potatoes are often eaten with other vegetables.

So, Are Potatoes Bad for Us?A primary reason we care about blood pressure is because we care about the consequences. In two studies done in Sweden, where they primarily eat their potatoes boiled, no evidence was found that potato consumption was associated with the risk of major cardiovascular disease; no relationship was found between potato consumption and risk of premature death in Southern Italy either. In the United States, though, potato consumption has been associated with increased mortality: a 65 percent increased risk of dying from heart disease, a 26 percent increased risk of fatal stroke, a 50 percent increased risk of dying from cancer, and increased risk of dying from all causes put together. However, all of that disappeared after adjustment for confounding factors. In other words, it wasn’t the potatoes at all. People who eat potatoes must just smoke more, drink more, or eat more saturated fat, for instance. Once all such other factors are considered, the link between potatoes and death disappears.

This was confirmed in the NIH-AARP study, the largest such study of diet and health in human history. If you just separate out the potatoes, researchers find they are not associated with increased risk of death—with the possible exception of french fries, which are associated with an increased risk of dying from cancer. Put all the studies together—20 in all—and no significant association has been found between potato consumption and mortality, though, again, fried potatoes may be the exception. Even if eaten just twice a week, fries may double one’s risk of dying prematurely, independently of other factors, but the consumption of unfried potatoes seemed to be neutral. (In terms of mortality, fried potatoes may not be as bad as fried meat—think fried chicken and fried fish—but that’s not saying much.)

Other whole plant foods—nuts, vegetables, fruits, and legumes (beans, split peas, chickpeas, and lentils)—are associated with living a longer life and significantly less risk of dying from cancer, dying from cardiovascular diseases like heart attacks, and 25 percent less chance of dying prematurely from all causes put together. However, no such protection is gained from potatoes for cancer, heart disease, or overall mortality. So, the fact that potatoes don’t seem to affect mortality can be seen as a downside. Remember, though, that potatoes aren’t like meat, which may actually actively shorten lifespan, but there may be an opportunity cost to eating white potatoes, since every bite of a potato is a lost opportunity to eat something even healthier—something that may actively enhance our lifespan.

So, potatoes are kind of a double-edged sword. The reason that potato consumption may just have a neutral impact on mortality risk is that all the fiber, vitamin C, and potassium in white potatoes might be counterbalanced by the detrimental effects of their high glycemic index, which I discuss in my video Glycemic Index of Potatoes: Why You Should Chill and Reheat Them. Not only are high glycemic impact diets robustly associated with developing type 2 diabetes, but current evidence suggests that this relationship is cause-and-effect.

The Potato Glycemic IndexFoods with a glycemic index (GI) above 70 are classified as high-GI foods, and those with a GI lower than 55 are low-GI foods. Pure sugar water, for example, is often standardized at 100, and white bread and white potatoes are high glycemic index foods.

Is there any way we can lower the glycemic index of potatoes? When potatoes are boiled, then cooled in the refrigerator, some of the starch crystallizes into a form that can no longer be broken down by the starch-munching enzymes in our gut. When put to the test, researchers actually saw a dramatic drop in glycemic index in cold versus hot potatoes. So, by consuming potatoes as potato salad, for instance, we can get nearly a 40 percent lower glycemic impact. The chilling effect might, therefore, also slow the rate at which the starch is broken down and absorbed. So, individuals wishing to minimize dietary glycemic index may be advised to precook potatoes and consume them cold or reheated. The downside of eating potatoes cold is that they might not be as satiating as eating hot potatoes, but we may get the best of both worlds by cooling them and then reheating them, which is exactly what was done in a famous study I profiled in my book How Not to Diet. The single most satiating food out of the dozens tested was boiled then cooled then reheated potatoes.

There’s an appetite-suppressing protein in potatoes called potato protease inhibitor II, but the way potatoes are prepared makes a difference. Both boiled and mashed potatoes are significantly more satiating than french fries. That was for fried french fries, though. What about baked fries? Individuals had a big drop in appetite after eating boiled mashed potatoes, compared to white rice or white pasta, which is right where fried french fries were, as well as baked french fries.

Do Potatoes Spike Our Blood Sugar?White potatoes have a high glycemic index, as I mentioned, and consumption of high glycemic impact foods may increase the risk of diabetes. Normally after a meal, we’d like our blood sugars to just gently, naturally rise and fall, but with high glycemic foods like potatoes, we can get an exaggerated blood sugar spike. That leads our body to over-compensate with insulin, forcing our blood sugars lower than when we started, which results in negative metabolic consequences––such as a rise in triglyceride fats in the blood. However, potatoes are a good source of potassium, vitamin C, and polyphenols, which may counterbalance the glycemic impact. This may explain why potatoes appear to have a neutral effect when it comes to lifespan, unlike other whole plant foods that have been associated with actively living longer.

How to Reduce the GI of PotatoesAside from the chill-and-reheat method to dramatically lower the glycemic index of white potatoes, is there another way? Yes, and it’s the same way we make everything better in our nutritional life: Add broccoli. As I detail in How to Reduce the Glycemic Impact of Potatoes, the co-consumption of two servings of cooked broccoli with mashed potatoes immediately cuts the insulin demand by nearly 40 percent. In contrast, adding chicken breast makes matters worse, and adding tuna fish is even worse still, nearly doubling the amount of insulin our body pumps out.

Why does plant protein make things better, but animal protein make things worse? Because decreased consumption of branched-chain amino acids improves metabolic health. I cover this in my book How Not to Diet, as well as my video on the topic.

Something else can help, too: vinegar. Simply chilling potatoes may cut down on blood sugar and insulin spikes, but to get significant drops in both, just add about a tablespoon of vinegar (even plain white distilled vinegar) to drop levels by 30 to 40 percent. Just one to two tablespoons a day of vinegar diluted in water can significantly improve both short- and long-term blood sugar control in people with diabetes, which is why clinicians may want to incorporate vinegar consumption as part of their dietary advice for their patients with diabetes.

March 6, 2025

Plant-Based Meats and Puberty, Obesity, and Fracture Risk

What are the effects of plant-based meats on premature puberty, childhood obesity, and hip fracture risk?

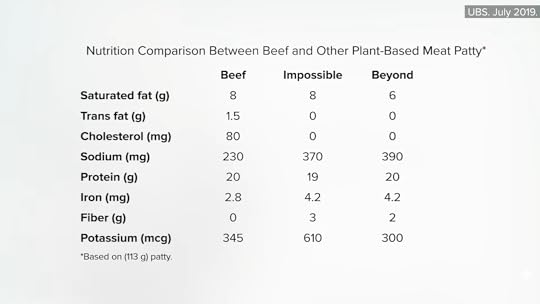

As noted in an editorial in the Journal of the American Medical Association on plant-based meats, if you look only at the nutrition facts information for a conventional burger versus a Beyond Meat or Impossible Burger, as seen here and at 0:20 in my video Plant-Based Meat Substitutes Put to the Test, you wouldn’t necessarily be able to predict the health consequences without further studies.

We’ve had plant-based meats in the marketplace for more than a century, though, as you can see in this ad for “good eating” Protose, below and at 0:35 in my video. Dr. John Harvey Kellogg filed a patent for Protose, what he called “the modern vegetable meat,” in 1899.

Of course, products like tempeh and tofu have been eaten throughout Asia for centuries, but I think of those as separate foods in their own right, as opposed to products intentionally designed to mimic the taste and texture of meat. With such a rich history, harkening back to the days of pass-the-Proteena—another great ad here and at 1:06 in my video—you’d think there’d be some studies of consumers—and indeed, there are.

Researchers have found, for example, that girls who eat meat may start their periods six months earlier than girls who don’t. Is the earlier menstruation because the meat-eating girls were eating a lot of protein and fat? No, because vegetarian girls who instead ate meat analogs, like veggie burgers and veggie dogs, were able to delay menstruation by nine months. Of course, it’s hard to tease out how much of that is just from avoiding meat, but compared with girls who ate meat a few times a week, those who ate meat a few times a day had a significantly earlier age of first menstruation. This may help explain why childhood meat consumption is linked to breast cancer later in life, since the earlier you start your period, the higher your lifetime risk.

Now, obesity itself may contribute to the early onset of puberty in girls, so that could be another factor. Studies have suggested that “vegetarian children tend to be lighter and leaner than nonvegetarian children,” but veg kids aren’t smaller in general, though. Vegetarian boys and girls may measure to be about an inch taller than their classmates; they just aren’t as wide. So, the fact that girls who eat plant-based meats may be less likely to experience premature puberty may, in part, be because they were leaner.

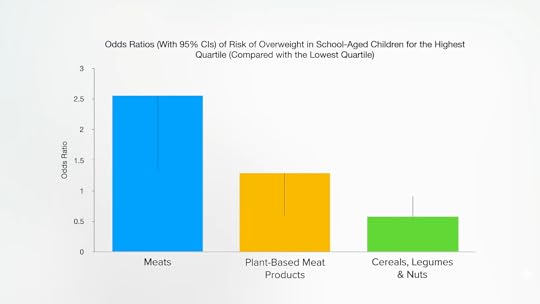

Indeed, as shown here and at 2:48 in my video, childhood obesity research found that meat consumption seems to double the odds of schoolchildren becoming overweight, compared to plant-based meat. Now, whole plant food sources of protein, such as beans, do even better and are associated with halving the odds of kids becoming overweight.

This is why I consider plant-based meats like the Impossible Burger and Beyond Meat more of a useful stepping stone towards a healthier diet, rather than the endgame ideal. The same amount of protein in a bean burrito would be better in nearly every way, as you can see here and at 3:05 in my video.

Similarly, in terms of hip fracture risk, in the Adventist Health Study–2, which followed tens of thousands of men and women for years, researchers found that daily intake of plant-based meats appeared to reduce the risk of hip fracture by nearly half, but daily intake of legumes—beans, split peas, chickpeas, and lentils—may drop the risk of hip fracture by even more—by nearly two-thirds.

This is the fourth in a nine-part series on plant-based meats. If you missed the first three, see the related posts below.

Stay tuned for:

The Health Effects of Mycoprotein (Quorn) Products vs. BCAAs in Meat What About the Heme in Impossible Burgers? Does Heme Iron Cause Cancer? Heme-Induced N-Nitroso Compounds and Fat Oxidation Is Heme the Reason Meat Is Carcinogenic?March 4, 2025

Are Plant-Based Meats Good for Us?

What are the different impacts of plant protein versus animal protein, and do the benefits of plant proteins translate to plant protein isolates?

Are plant-based burgers healthy or not? The answer is: Compared to what? Eating is kind of a zero-sum game where every food has an opportunity cost. Each time we put something in our mouth, it’s a lost opportunity to eat something even healthier. So, if we want to know if something is healthy, we have to compare it to what we’d be eating instead. For example, are eggs healthy? Compared to a breakfast sausage link, yes, but compared to oatmeal? Not even close. Sausage is considered a Group 1 carcinogen. We know that consumption of processed meat causes cancer. Each 50-gram serving a day (equal to about one or two breakfast sausages) has been linked to an 18 percent higher risk of colorectal cancer. In fact, the risk of getting colorectal cancer from eating those daily sausages is about the same as the increased risk of lung cancer we’d get from breathing in secondhand cigarette smoke living with a smoker. So, compared to sausage, eggs are healthy, but compared to oatmeal, eggs are not.

When it comes to Beyond Meat and Impossible Foods plant-based burger patties, they may be better in that they have less saturated fat than conventional meat burgers, but if you really want less saturated fat, plant-based meats are no match for unprocessed plant foods, such as lentils and beans. And lentil soup or a bean burrito could certainly fill the same culinary niche as a lunchtime burger. But, if you are going to have some kind of burger, it’s easy to argue that plant-based versions are more healthful, as seen below and at 1:43 in my video Plant-Based Protein: Are Pea and Soy Protein Isolates Harmful?.

There is a sodium issue with those plant-based patties, though, and they aren’t that much lower in saturated fat. That is due to coconut oil, which is as bad as animal fat, so there isn’t much advantage on that front.

The total protein is similar across the board. Does that matter? Is there any advantage to eating protein from plants over animals? Let’s look at the association between plant and animal protein intake and mortality. In the twin Harvard cohorts, which followed more than 100,000 men and women over decades, researchers wrote: “After adjusting for other dietary and lifestyle factors, animal protein intake was associated with a higher risk for mortality, particularly CVD mortality,” that is, dying from cardiovascular disease, “whereas higher plant protein intake was associated with lower all-cause mortality,” meaning a lower risk of dying from all causes put together. So, “replacing animal protein of various origins with plant protein was associated with lower mortality,” especially if processed meat and egg protein were replaced, as they were the worst.

When it comes to living a longer life, plant protein sources beat out each and every animal protein source. Not just better than bacon and eggs, but better than burgers, chicken, turkey, fish, and dairy protein, as shown here and at 2:53 in my video.

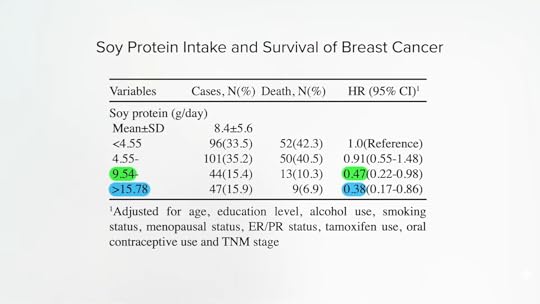

Together with other studies, these “findings support the importance of protein sources for the long-term health outcome and suggest that plants constitute a preferred protein source compared with animal foods.” Why? Well, “unlike animal protein, plant protein has not been associated with increased insulin-like growth factor 1 levels.” (IGF-1 is a cancer-promoting growth hormone.) Soy protein is similar enough to animal protein that, at high enough doses, like eating two Impossible burgers a day, our IGF-1 may get a bump. But the only reason we care about IGF-1 is cancer risk, and, if anything, “higher soy intake is associated with a decreased risk of breast and prostate cancer.”

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis found that “soy protein intake was associated with a decreased risk in the mortality of breast cancer,” for instance. “A 12% reduction in breast cancer death was observed for each 5-g/day increase in soy protein intake.” But, as shown below and at 4:07 in my video, the high-soy groups in these studies were on the order of more than 16 grams a day, which was associated with an incredible 62 percent lower risk of dying from breast cancer. More than 10 daily grams of soy protein may be good, associated with nearly halving breast cancer mortality risk, and getting more than 16 grams a day may be better, which is like one Impossible burger a day. (We simply don’t know what happens at consumption levels far above that.)

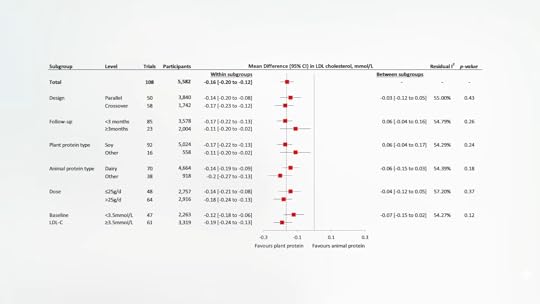

Plant protein has also “been linked to lower blood pressure, reduced low-density lipoprotein [LDL cholesterol] levels, and improved insulin sensitivity. Substitution of plant protein for animal protein has been related to a lower incidence of CVD [cardiovascular disease] and type 2 diabetes.” Indeed, 21 different studies following nearly half a million people found that “high…animal protein intakes are associated with an increased risk of T2DM [type 2 diabetes], whereas moderate plant protein intake is associated with a decreased risk of T2DM.” Those were just observational studies, though. The researchers tried to control for other dietary and lifestyle factors, but cause and effect can’t be proven until it’s put to the test.

Enter “Effect of Replacing Animal Protein with Plant Protein on Glycemic [Blood Sugar] Control in Diabetes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials.” Researchers found that replacing only about a third of protein from animal sources with plant sources yielded significant improvements in long-term blood sugar control, fasting blood sugars, and insulin.

Same with cholesterol. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials on the effect of plant protein on blood fats again found that replacing animal protein with plant protein decreases LDL cholesterol. What’s more, this benefit occurs whether you start out with high or low cholesterol, whether you’re replacing dairy, or meat and eggs, and whether you’re swapping in soy or other plant proteins, as seen here and at 5:31 in my video.

We’ve known about soy’s beneficial effects on cholesterol for nearly 40 years, but other sources of plant protein can be helpful, too. However, in the case of plant-based burgers like Beyond Beef and the Impossible Burger, beef isn’t being replaced with beans. Those products are mostly isolated plant proteins—mostly pea protein isolate in Beyond Meat products and concentrated soy protein in Impossible Foods products. If you isolate the plant proteins themselves, will you still get benefits? Surprisingly, yes. Check it out.

The researchers concluded: “Interestingly, our…analyses did not find a significant difference between protein isolate products and whole food sources for any given endpoint, suggesting that the cholesterol-lowering effects are at least, in part, attributable to the plant protein itself rather than just the associated nutrients.” So, it isn’t just because plant protein travels with fiber or less saturated fat. Plant proteins break down into a different distribution of amino acids. So, if you give people arginine, an amino acid found more in plant foods, that alone can bring down cholesterol, for example. And the plant protein concentrates used in these meat-free products aren’t just pure protein; they retain some active compounds, such as phytosterols and antioxidants, which also can have beneficial effects.

This is the third in a series on plant-based meats. If you missed the first two, see The Environmental Impacts of Plant-Based Meat Substitutes and Are Beyond Meat and the Impossible Burger Healthy?.

Check the related posts below for the upcoming videos on plant-based meats.

February 27, 2025

Celebrating Food, Activism, and Black History Month with Jenné Claiborne

We had the pleasure of talking with Jenné Claiborne about her work, food, Black History Month, and her new cookbook. We hope you enjoy this interview and her recipe for her Amazing Edamame Salad.

Please tell us a little bit about yourself and your work.

I am the vegan chef, cookbook author, and content creator behind Sweet Potato Soul. Since 2010, I have been blogging and sharing delicious and nutritious vegan recipes with hungry readers. Committing to a vegan diet in 2011 set the course for my life and career in the best way, and I have never looked back.

How did you learn how to cook? What is your culinary story?

I learned how to cook by observing and assisting my grandmother and father in the kitchen. My dad was raised vegan, so I was familiar with plant-based cooking from a very young age. My grandmother is a classic soul food cook, but she made delicious and creative changes to her way of cooking when my family decided to stop eating red meat well before my birth. Growing up, I saw cooking as a way to creatively express love for family and friends, while also nourishing the body. My cuisine has always been inspired by my family, but also by the travels I’ve taken all over the world.

In your experience, how have you found food to tell a story and shape health, culture, and community?

Food is truly everything. You are what you eat. Food can tell a story about your origins and culture, your access, your knowledge, and your values. As a vegan who is inspired by soul food, global cuisine, and seasonality, I use food to tell a story of our abundantly beautiful world.

How do you educate people about whole food, plant-based nutrition, and what do you envision as the way forward to help expand whole food, plant-based options regionally?

I seek to educate people through setting an example of what a healthy vegan can be. My background is as a private chef in New York City, not a nutritionist or doctor. Without medical qualifications, I find that setting a good example and providing delicious recipes are the best ways I can educate those who are looking for inspiration and guidance.

As the author of the cookbook Sweet Potato Soul , how would you describe southern flavors and their history?

I’d describe southern flavors as seasonal, bold, colorful, and delicious. Like everywhere in the world, southern cuisine is very much influenced by what is available in the region seasonally. Traditionally, that meant a lot of leafy greens, whole grains, legumes/beans, and smoked foods.

What are some of your favorite ways to incorporate these flavors into plant-based dishes?

I adore classic southern foods and flavors, and they are all so easy to veganize. For example, I grew up eating smoky collard greens, cornbread, sweet potato pie, biscuits, and BBQ. I have found simple and nutritious ways to veganize them all by using wholesome ingredients like smoked paprika, flax egg, non-dairy milk, and mushrooms.

What does Black History Month mean to you?

BHM to me is a great time to learn about and celebrate the contributions of Black folks to American culture and institutions. Black people have made so many overlooked contributions, and BHM is a great time to recognize them, especially in the area of food. My favorite example is George Washington Carver, who revolutionized the production and use of peanuts, as well as sweet potatoes (my favorite vegetable).

AMAZING EDAMAME SALADMakes 2 to 4 servings

Originally published on Jenné’s website.

Ingredients12 oz bag frozen and shelled edamame (also known as mukimame)1 cup shredded red cabbage2 shredded carrots (about 1 cup)½ red bell pepper, diced2 scallions¼ cup fresh minced cilantro¼ cup smooth almond butter, stirred well2 tbsp freshly squeezed lime juice2 tbsp Umami Sauce2 tsp Date Syrup1-inch piece fresh ginger, minced or grated1 garlic clove, minced or grated½ cup raw chopped almondsNote: This recipe has been adapted to meet NutritionFacts.org standards.

InstructionsBring a large saucepan of water to a boil over high heat. Add the edamame, then boil for 5 minutes or until tender. Drain and let cool at room temperature for 5 to 10 minutes, until the edamame are cool to the touch.In a large mixing bowl, add the edamame, red cabbage, carrots, bell pepper, scallions, and cilantro.In a small whisking bowl, combine the almond butter, lime juice, Umami Sauce, Date Syrup, ginger, and garlic. Whisk well until smooth and creamy.Pour the almond dressing over the vegetables. Toss well to combine. Cover and refrigerate the salad for an hour to marinate or serve immediately, garnished with chopped almonds.

InstructionsBring a large saucepan of water to a boil over high heat. Add the edamame, then boil for 5 minutes or until tender. Drain and let cool at room temperature for 5 to 10 minutes, until the edamame are cool to the touch.In a large mixing bowl, add the edamame, red cabbage, carrots, bell pepper, scallions, and cilantro.In a small whisking bowl, combine the almond butter, lime juice, Umami Sauce, Date Syrup, ginger, and garlic. Whisk well until smooth and creamy.Pour the almond dressing over the vegetables. Toss well to combine. Cover and refrigerate the salad for an hour to marinate or serve immediately, garnished with chopped almonds.You can find Jenné on her blog, Instagram, and Youtube. Her new cookbook is available wherever books are sold.